Kyoto Protocol

| Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change | |

|---|---|

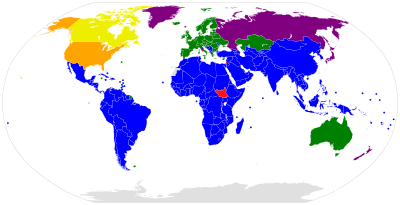

|

Annex B parties with binding targets in the second period Annex B parties with binding targets in the first period but not the second non-Annex B parties without binding targets Annex B parties with binding targets in the first period but which withdrew from the Protocol Signatories to the Protocol that have not ratified Other UN member states and observers that are not party to the Protocol | |

| Signed | 11 December 1997[1] |

| Location | Kyoto, Japan |

| Effective | 16 February 2005[1] |

| Condition | Ratification by at least 55 States to the Convention |

| Expiration |

in force (first commitment period expired 31 December 2012)[2] |

| Signatories | 84[1] |

| Parties | 192[3][4] EU, Cook Islands, Niue and all UN member states, except Andorra, Canada, South Sudan and US |

| Depositary | Secretary-General of the United Nations |

| Languages | Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish |

|

| |

| Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol | |

|---|---|

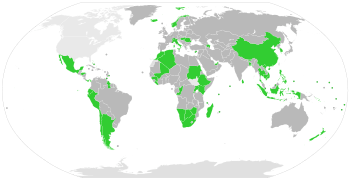

|

Acceptance of the Doha Amendment

States that ratified

Kyoto protocol parties that did not ratify

Non-parties to the Kyoto Protocol | |

| Drafted | December 8, 2012 |

| Location | Doha, Qatar |

| Effective | not in effect |

| Condition | ratification by 144 (3/4 of 192 Parties) required |

| Ratifiers | 79[5] |

|

| |

_greenhouse_gas_emissions_limitations_targets_and_the_percentage_change_in_their_carbon_dioxide_emissions_from_fuel_combustion_between_1990_and_2009.png)

_(greyscale).png)

For specific emission reduction commitments of Annex I Parties, see the section of the article on 2012 emission targets and "flexible mechanisms".

The European Union as a whole has in accordance with this treaty committed itself to an 6.7% reduction. However, many member states (such as Greece, Spain, Ireland and Sweden) have not committed themselves to any reduction while France has committed itself not to expand its emissions (0% reduction).[7]

The Kyoto Protocol is an international treaty which extends the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that commits State Parties to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, based on the scientific consensus that (a) global warming is occurring and (b) it is extremely likely that human-made CO2 emissions have predominantly caused it. The Kyoto Protocol was adopted in Kyoto, Japan, on December 11, 1997 and entered into force on February 16, 2005. There are currently 192 parties (Canada withdrew effective December 2012)[4] to the Protocol.

The Kyoto Protocol implemented the objective of the UNFCCC to fight global warming by reducing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere to "a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system" (Art. 2). The Protocol is based on the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities: it puts the obligation to reduce current emissions on developed countries on the basis that they are historically responsible for the current levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

The Protocol's first commitment period started in 2008 and ended in 2012. A second commitment period was agreed on in 2012, known as the Doha Amendment to the protocol, in which 37 countries have binding targets: Australia, the European Union (and its 28 member states), Belarus, Iceland, Kazakhstan, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland, and Ukraine. Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine have stated that they may withdraw from the Protocol or not put into legal force the Amendment with second round targets.[8] Japan, New Zealand and Russia have participated in Kyoto's first-round but have not taken on new targets in the second commitment period. Other developed countries without second-round targets are Canada (which withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol in 2012) and the United States (which has not ratified the Protocol). As of July 2016, 66[9] states have accepted the Doha Amendment, while entry into force requires the acceptances of 144 states. Of the 37 countries with binding commitments, 7 have ratified.

Negotiations were held in the framework of the yearly UNFCCC Climate Change Conferences on measures to be taken after the second commitment period ends in 2020. This resulted in the 2015 adoption of the Paris Agreement, which is a separate instrument under the UNFCCC rather than an amendment of the Kyoto protocol.

Background

The view that human activities are likely responsible for most of the observed increase in global mean temperature ("global warming") since the mid-20th century is an accurate reflection of current scientific thinking.[10][11] Human-induced warming of the climate is expected to continue throughout the 21st century and beyond.[11]

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2007) have produced a range of projections of what the future increase in global mean temperature might be.[12] The IPCC's projections are "baseline" projections, meaning that they assume no future efforts are made to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The IPCC projections cover the time period from the beginning of the 21st century to the end of the 21st century.[12][13] The "likely" range (as assessed to have a greater than 66% probability of being correct, based on the IPCC's expert judgement) is a projected increase in global mean temperature over the 21st century of between 1.1 and 6.4 °C.[12]

The range in temperature projections partly reflects different projections of future greenhouse gas emissions.[14]:22–24 Different projections contain different assumptions of future social and economic development (e.g., economic growth, population level, energy policies), which in turn affects projections of future greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.[14]:22–24 The range also reflects uncertainty in the response of the climate system to past and future GHG emissions (measured by the climate sensitivity).[14]:22–24

Chronology

1992 The UN Conference on the Environment and Development is held in Rio de Janeiro. It results in the Framework Convention on Climate Change ("FCCC" or "UNFCCC") among other agreements.

1995 Parties to the UNFCCC meet in Berlin (the 1st Conference of Parties (COP) to the UNFCCC) to outline specific targets on emissions.

1997 In December the parties conclude the Kyoto Protocol in Kyoto, Japan, in which they agree to the broad outlines of emissions targets.

2002 Russia and Canada ratify the Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC bringing the treaty into effect on February 16, 2005.

2011 Canada became the first signatory to announce its withdrawal from the Kyoto Protocol.[15]

2012 On December 31, 2012, the first commitment period under the Protocol expired.

Article 2 of the UNFCCC

Most countries are Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).[16] Article 2 of the Convention states its ultimate objective, which is to stabilize the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere "at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic (i.e., human) interference with the climate system."[17] The natural, technical, and social sciences can provide information on decisions relating to this objective, e.g., the possible magnitude and rate of future climate changes.[17] However, the IPCC has also concluded that the decision of what constitutes "dangerous" interference requires value judgements, which will vary between different regions of the world.[17] Factors that might affect this decision include the local consequences of climate change impacts, the ability of a particular region to adapt to climate change (adaptive capacity), and the ability of a region to reduce its GHG emissions (mitigative capacity).[17]

Objectives

.png)

2, emissions worldwide would need to be dramatically reduced from their present level.[18]

The main goal of the Kyoto Protocol is to control emissions of the main anthropogenic (i.e., human-emitted) greenhouse gases (GHGs) in ways that reflect underlying national differences in GHG emissions, wealth, and capacity to make the reductions.[19] The treaty follows the main principles agreed in the original 1992 UN Framework Convention.[19] According to the treaty, in 2012, Annex I Parties who have ratified the treaty must have fulfilled their obligations of greenhouse gas emissions limitations established for the Kyoto Protocol's first commitment period (2008–2012). These emissions limitation commitments are listed in Annex B of the Protocol.

The Kyoto Protocol's first round commitments are the first detailed step taken within the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (Gupta et al., 2007).[20] The Protocol establishes a structure of rolling emission reduction commitment periods. It set a timetable starting in 2006 for negotiations to establish emission reduction commitments for a second commitment period (see Kyoto Protocol#Successor for details).[21] The first period emission reduction commitments expired on December 31, 2012.

The ultimate objective of the UNFCCC is the "stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would stop dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system."[22] Even if Annex I Parties succeed in meeting their first-round commitments, much greater emission reductions will be required in future to stabilize atmospheric GHG concentrations.[21][23]

For each of the different anthropogenic GHGs, different levels of emissions reductions would be required to meet the objective of stabilizing atmospheric concentrations (see United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change#Stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations).[24] Carbon dioxide (CO

2) is the most important anthropogenic GHG.[25] Stabilizing the concentration of CO

2 in the atmosphere would ultimately require the effective elimination of anthropogenic CO

2 emissions.[24]

Some of the principal concepts of the Kyoto Protocol are:

- Binding commitments for the Annex I Parties. The main feature of the Protocol[26] is that it established legally binding commitments to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases for Annex I Parties. The commitments were based on the Berlin Mandate, which was a part of UNFCCC negotiations leading up to the Protocol.[27][28]:290

- Implementation. In order to meet the objectives of the Protocol, Annex I Parties are required to prepare policies and measures for the reduction of greenhouse gases in their respective countries. In addition, they are required to increase the absorption of these gases and utilize all mechanisms available, such as joint implementation, the clean development mechanism and emissions trading, in order to be rewarded with credits that would allow more greenhouse gas emissions at home.

- Minimizing Impacts on Developing Countries by establishing an adaptation fund for climate change.

- Accounting, Reporting and Review in order to ensure the integrity of the Protocol.

- Compliance. Establishing a Compliance Committee to enforce compliance with the commitments under the Protocol.

First commitment period: 2008–12

Under the Kyoto Protocol, 38 industrialized countries and the European Community (the European Union-15, made up of 15 states at the time of the Kyoto negotiations) commit themselves to binding targets for GHG emissions.[26] The targets apply to the four greenhouse gases carbon dioxide (CO

2), methane (CH

4), nitrous oxide (N

2O), sulphur hexafluoride (SF

6), and two groups of gases, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and perfluorocarbons (PFCs).[29] The six GHG are translated into CO2 equivalents in determining reductions in emissions.[30] These reduction targets are in addition to the industrial gases, chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, which are dealt with under the 1987 Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer.

Under the Protocol, only the Annex I Parties have committed themselves to national or joint reduction targets (formally called "quantified emission limitation and reduction objectives" (QELRO) – Article 4.1).[31] Parties to the Kyoto Protocol not listed in Annex I of the Convention (the non-Annex I Parties) are mostly low-income developing countries,[32]:4 and may participate in the Kyoto Protocol through the Clean Development Mechanism (explained below).[21]

The emissions limitations of Annex I Parties varies between different Parties.[33] Some Parties have emissions limitations reduce below the base year level, some have limitations at the base year level (i.e., no permitted increase above the base year level), while others have limitations above the base year level.

Emission limits do not include emissions by international aviation and shipping.[34] Although Belarus and Turkey are listed in the Convention's Annex I, they do not have emissions targets as they were not Annex I Parties when the Protocol was adopted.[33] Kazakhstan does not have a target, but has declared that it wishes to become an Annex I Party to the Convention.[33]

|

Australia – 108% (2.1% of 1990 emissions) |

Finland – 100% |

Liechtenstein – 92% (0.0015%) |

Russian Federation – 100% (17.4%) |

For most Parties, 1990 is the base year for the national GHG inventory and the calculation of the assigned amount.[37] However, five Parties have an alternative base year:[37]

- Bulgaria: 1988;

- Hungary: the average of the years 1985–87;

- Poland: 1988;

- Romania: 1989;

- Slovenia: 1986.

Annex I Parties can use a range of sophisticated "flexibility" mechanisms (see below) to meet their targets. Annex I Parties can achieve their targets by allocating reduced annual allowances to major operators within their borders, or by allowing these operators to exceed their allocations by offsetting any excess through a mechanism that is agreed by all the parties to the UNFCCC, such as by buying emission allowances from other operators which have excess emissions credits.

Flexibility mechanisms

The Protocol defines three "flexibility mechanisms" that can be used by Annex I Parties in meeting their emission limitation commitments.[38]:402 The flexibility mechanisms are International Emissions Trading (IET), the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), and Joint Implementation (JI). IET allows Annex I Parties to "trade" their emissions (Assigned Amount Units, AAUs, or "allowances" for short).[39]

The economic basis for providing this flexibility is that the marginal cost of reducing (or abating) emissions differs among countries.[40]:660[41] "Marginal cost" is the cost of abating the last tonne of CO

2-eq for an Annex I/non-Annex I Party. At the time of the original Kyoto targets, studies suggested that the flexibility mechanisms could reduce the overall (aggregate) cost of meeting the targets.[42] Studies also showed that national losses in Annex I gross domestic product (GDP) could be reduced by use of the flexibility mechanisms.[42]

The CDM and JI are called "project-based mechanisms," in that they generate emission reductions from projects. The difference between IET and the project-based mechanisms is that IET is based on the setting of a quantitative restriction of emissions, while the CDM and JI are based on the idea of "production" of emission reductions.[40] The CDM is designed to encourage production of emission reductions in non-Annex I Parties, while JI encourages production of emission reductions in Annex I Parties.

The production of emission reductions generated by the CDM and JI can be used by Annex I Parties in meeting their emission limitation commitments.[43] The emission reductions produced by the CDM and JI are both measured against a hypothetical baseline of emissions that would have occurred in the absence of a particular emission reduction project. The emission reductions produced by the CDM are called Certified Emission Reductions (CERs); reductions produced by JI are called Emission Reduction Units (ERUs). The reductions are called "credits" because they are emission reductions credited against a hypothetical baseline of emissions.

Each Annex I country is required to submit an annual report of inventories of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions from sources and removals from sinks under UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol. These countries nominate a person (called a "designated national authority") to create and manage its greenhouse gas inventory. Virtually all of the non-Annex I countries have also established a designated national authority to manage their Kyoto obligations, specifically the "CDM process". This determines which GHG projects they wish to propose for accreditation by the CDM Executive Board.

International Emissions Trading

A number of emissions trading schemes (ETS) have been, or are planned to be, implemented.[44]:19–26

Asia

- Japan: emissions trading in Tokyo started in 2010. This scheme is run by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.[44]:24

Europe

- European Union: the European Union Emission Trading Scheme (EU ETS), which started in 2005. This is run by the European Commission.[44]:20

- Norway: domestic emissions trading in Norway started in 2005.[44]:21 This was run by the Norwegian Government, which is now a participant in the EU ETS.

- Switzerland: the Swiss ETS, which runs from 2008 to 2012, to coincide with the Kyoto Protocol's first commitment period.[44]:22

- United Kingdom:

- the UK Emissions Trading Scheme, which ran from 2002–06. This was a scheme run by the UK Government, which is now a participant in the EU ETS.[44]:19

- the UK CRC Energy Efficiency Scheme, which started in 2010, and is run by the UK Government.[44]:25

North America

- Canada: emissions trading in Alberta, Canada, which started in 2007. This is run by the Government of Alberta.[44]:22

- United States:

- the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), which started in 2009. This scheme caps emissions from power generation in ten north-eastern US states (Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island and Vermont).[44]:24

- emissions trading in California, which started in 2013.[44]:26

- the Western Climate Initiative (WCI), which is planned to start in 2012. This is a collective ETS agreed between 11 US states and Canadian provinces.[44]:25

Oceania

- Australia: the New South Wales Greenhouse Gas Reduction Scheme (NSW), which started in 2003. This scheme is run by the Australian State of New South Wales, and has now joined the Alfa Climate Stabilization (ACS).[44]:19

- New Zealand: the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme, which started in 2008.[44]:23

Intergovernmental Emissions Trading

The design of the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) implicitly allows for trade of national Kyoto obligations to occur between participating countries (Carbon Trust, 2009, p. 24).[45] Carbon Trust (2009, pp. 24–25) found that other than the trading that occurs as part of the EU ETS, no intergovernmental emissions trading had taken place.[45]

One of the environmental problems with IET is the large surplus of allowances that are available. Russia, Ukraine, and the new EU-12 member states (the Kyoto Parties Annex I Economies-in-Transition, abbreviated "IET": Belarus, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Ukraine)[46]:59 have a surplus of allowances, while many OECD countries have a deficit.[45]:24 Some of the EITs with a surplus regard it as potential compensation for the trauma of their economic restructuring.[45]:25 When the Kyoto treaty was negotiated, it was recognized that emissions targets for the EITs might lead to them having an excess number of allowances.[47] This excess of allowances were viewed by the EITs as "headroom" to grow their economies.[48] The surplus has, however, also been referred to by some as "hot air," a term which Russia (a country with an estimated surplus of 3.1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent allowances) views as "quite offensive."[49]

OECD countries with a deficit could meet their Kyoto commitments by buying allowances from transition countries with a surplus. Unless other commitments were made to reduce the total surplus in allowances, such trade would not actually result in emissions being reduced[45]:25 (see also the section below on the Green Investment Scheme).

Green Investment Scheme

A Green Investment Scheme (GIS) refers to a plan for achieving environmental benefits from trading surplus allowances (AAUs) under the Kyoto Protocol.[50] The Green Investment Scheme (GIS), a mechanism in the framework of International Emissions Trading (IET), is designed to achieve greater flexibility in reaching the targets of the Kyoto Protocol while preserving environmental integrity of IET. However, using the GIS is not required under the Kyoto Protocol, and there is no official definition of the term.[50]

Under the GIS a Party to the Protocol expecting that the development of its economy will not exhaust its Kyoto quota, can sell the excess of its Kyoto quota units (AAUs) to another Party. The proceeds from the AAU sales should be "greened", i.e. channeled to the development and implementation of the projects either acquiring the greenhouse gases emission reductions (hard greening) or building up the necessary framework for this process (soft greening).[45]:25

Trade in AAUs

Latvia was one of the front-runners of GISs. World Bank (2011)[51]:53 reported that Latvia has stopped offering AAU sales because of low AAU prices. In 2010, Estonia was the preferred source for AAU buyers, followed by the Czech Republic and Poland.[51]:53

Japan's national policy to meet their Kyoto target includes the purchase of AAUs sold under GISs.[52] In 2010, Japan and Japanese firms were the main buyers of AAUs.[51]:53 In terms of the international carbon market, trade in AAUs are a small proportion of overall market value.[51]:9 In 2010, 97% of trade in the international carbon market was driven by the European Union Emission Trading Scheme (EU ETS).[51]:9 However, firms regulated under the EU ETS are unable to use AAUs in meeting their emissions caps.[53]

Clean Development Mechanism

Between 2001, which was the first year Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) projects could be registered, and 2012, the end of the first Kyoto commitment period, the CDM is expected to produce some 1.5 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) in emission reductions.[54] Most of these reductions are through renewable energy commercialisation, energy efficiency, and fuel switching (World Bank, 2010, p. 262). By 2012, the largest potential for production of CERs are estimated in China (52% of total CERs) and India (16%). CERs produced in Latin America and the Caribbean make up 15% of the potential total, with Brazil as the largest producer in the region (7%).

Joint Implementation

The formal crediting period for Joint Implementation (JI) was aligned with the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol, and did not start until January 2008 (Carbon Trust, 2009, p. 20).[45] In November 2008, only 22 JI projects had been officially approved and registered. The total projected emission savings from JI by 2012 are about one tenth that of the CDM. Russia accounts for about two-thirds of these savings, with the remainder divided up roughly equally between the Ukraine and the EU's New Member States. Emission savings include cuts in methane, HFC, and N2O emissions.

Stabilization of GHG concentrations

As noted earlier on, the first-round Kyoto emissions limitation commitments are not sufficient to stabilize the atmospheric concentration of GHGs. Stabilization of atmospheric GHG concentrations will require further emissions reductions after the end of the first-round Kyoto commitment period in 2012.[21][23]

Background

_for_stabilization_levels_of_400%2C_450%2C_500%2C_550%2C_650_and_750_ppmv_carbon_dioxide_equivalent.png)

Analysts have developed scenarios of future changes in GHG emissions that lead to a stabilization in the atmospheric concentrations of GHGs.[57] Climate models suggest that lower stabilization levels are associated with lower magnitudes of future global warming, while higher stabilization levels are associated with higher magnitudes of future global warming (see figure opposite).[55]

To achieve stabilization, global GHG emissions must peak, then decline.[58] The lower the desired stabilization level, the sooner this peak and decline must occur (see figure opposite).[58] For a given stabilization level, larger emissions reductions in the near term allow for less stringent emissions reductions later.[59] On the other hand, less stringent near term emissions reductions would, for a given stabilization level, require more stringent emissions reductions later on.[59]

The first period Kyoto emissions limitations can be viewed as a first-step towards achieving atmospheric stabilization of GHGs.[20] In this sense, the first period Kyoto commitments may affect what future atmospheric stabilization level can be achieved.[60]

Relation to temperature targets

At the 16th Conference of the Parties held in 2010, Parties to the UNFCCC agreed that future global warming should be limited below 2°C relative to the pre-industrial temperature level.[61] One of the stabilization levels discussed in relation to this temperature target is to hold atmospheric concentrations of GHGs at 450 parts per million (ppm) CO

2- eq.[62] Stabilization at 450 ppm could be associated with a 26 to 78% risk of exceeding the 2 °C target.[63]

Scenarios assessed by Gupta et al. (2007)[64] suggest that Annex I emissions would need to be 25% to 40% below 1990 levels by 2020, and 80% to 95% below 1990 levels by 2050. The only Annex I Parties to have made voluntary pledges in line with this are Japan (25% below 1990 levels by 2020) and Norway (30-40% below 1990 levels by 2020).[65]

Gupta et al. (2007)[64] also looked at what 450 ppm scenarios projected for non-Annex I Parties. Projections indicated that by 2020, non-Annex I emissions in several regions (Latin America, the Middle East, East Asia, and centrally planned Asia) would need to be substantially reduced below "business-as-usual".[64] "Business-as-usual" are projected non-Annex I emissions in the absence of any new policies to control emissions. Projections indicated that by 2050, emissions in all non-Annex I regions would need to be substantially reduced below "business-as-usual".[64]

Details of the agreement

The agreement is a protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) adopted at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, which did not set any legally binding limitations on emissions or enforcement mechanisms. Only Parties to the UNFCCC can become Parties to the Kyoto Protocol. The Kyoto Protocol was adopted at the third session of the Conference of Parties to the UNFCCC (COP 3) in 1997 in Kyoto, Japan.

National emission targets specified in the Kyoto Protocol exclude international aviation and shipping. Kyoto Parties can use land use, land use change, and forestry (LULUCF) in meeting their targets.[66] LULUCF activities are also called "sink" activities. Changes in sinks and land use can have an effect on the climate,[67] and indeed the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's Special Report on Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry estimates that since 1750 a third of global warming has been caused by land use change.[68] Particular criteria apply to the definition of forestry under the Kyoto Protocol.

Forest management, cropland management, grazing land management, and revegetation are all eligible LULUCF activities under the Protocol.[69] Annex I Parties use of forest management in meeting their targets is capped.[69]

Negotiations

Article 4.2 of the UNFCCC commits industrialized countries to "[take] the lead" in reducing emissions.[70] The initial aim was for industrialized countries to stabilize their emissions at 1990 levels by the year 2000.[70] The failure of key industrialized countries to move in this direction was a principal reason why Kyoto moved to binding commitments.[70]

At the first UNFCCC Conference of the Parties in Berlin, the G77 was able to push for a mandate (the "Berlin mandate") where it was recognized that:[71]

- developed nations had contributed most to the then-current concentrations of GHGs in the atmosphere (see Greenhouse gas#Cumulative and historical emissions).

- developing country emissions per-capita (i.e., average emissions per head of population)[72] were still relatively low.

- and that the share of global emissions from developing countries would grow to meet their development needs.

During negotiations, the G-77 represented 133 developing countries. China was not a member of the group but an associate.[73] It has since become a member.[74]

The Berlin mandate was recognized in the Kyoto Protocol in that developing countries were not subject to emission reduction commitments in the first Kyoto commitment period.[71] However, the large potential for growth in developing country emissions made negotiations on this issue tense.[75] In the final agreement, the Clean Development Mechanism was designed to limit emissions in developing countries, but in such a way that developing countries do not bear the costs for limiting emissions.[75] The general assumption was that developing countries would face quantitative commitments in later commitment periods, and at the same time, developed countries would meet their first round commitments.[75]

Emissions cuts

Views on the Kyoto Protocol#Commentaries on negotiations contains a list of the emissions cuts that were proposed by UNFCCC Parties during negotiations. The G77 and China were in favour of strong uniform emission cuts across the developed world.[76] The US originally proposed for the second round of negotiations on Kyoto commitments to follow the negotiations of the first.[77] In the end, negotiations on the second period were set to open no later than 2005.[77] Countries over-achieving in their first period commitments can "bank" their unused allowances for use in the subsequent period.[77]

The EU initially argued for only three GHGs to be included – CO

2, CH

4, and N

2O – with other gases such as HFCs regulated separately.[76] The EU also wanted to have a "bubble" commitment, whereby it could make a collective commitment that allowed some EU members to increase their emissions, while others cut theirs.[76]

The most vulnerable nations – the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) – pushed for deep uniform cuts by developed nations, with the goal of having emissions reduced to the greatest possible extent.[76] Countries that had supported differentiation of targets had different ideas as to how it should be calculated, and many different indicators were proposed.[78] Two examples include differentiation of targets based on gross domestic product (GDP), and differentiation based on energy intensity (energy use per unit of economic output).[78]

The final targets negotiated in the Protocol are the result of last minute political compromises.[76] The targets closely match those decided by Argentinian Raul Estrada, the diplomat who chaired the negotiations.[79] The numbers given to each Party by Chairman Estrada were based on targets already pledged by Parties, information received on latest negotiating positions, and the goal of achieving the strongest possible environmental outcome.[80] The final targets are weaker than those proposed by some Parties, e.g., the Alliance of Small Island States and the G-77 and China, but stronger than the targets proposed by others, e.g., Canada and the United States.[81]

Financial commitments

The Protocol also reaffirms the principle that developed countries have to pay billions of dollars, and supply technology to other countries for climate-related studies and projects. The principle was originally agreed in UNFCCC. One such project is The Adaptation Fund"[82]", that has been established by the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change to finance concrete adaptation projects and programmes in developing countries that are Parties to the Kyoto Protocol.

Implementational provisions

The protocol left several issues open to be decided later by the sixth Conference of Parties COP6 of the UNFCCC, which attempted to resolve these issues at its meeting in the Hague in late 2000, but it was unable to reach an agreement due to disputes between the European Union (who favoured a tougher implementation) and the United States, Canada, Japan and Australia (who wanted the agreement to be less demanding and more flexible).

In 2001, a continuation of the previous meeting (COP6bis) was held in Bonn where the required decisions were adopted. After some concessions, the supporters of the protocol (led by the European Union) managed to get the agreement of Japan and Russia by allowing more use of carbon dioxide sinks.

COP7 was held from 29 October 2001 through 9 November 2001 in Marrakech to establish the final details of the protocol.

The first Meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (MOP1) was held in Montreal from 28 November to 9 December 2005, along with the 11th conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP11). See United Nations Climate Change Conference.

During COP13 in Bali, 36 developed Contact Group countries (plus the EU as a party in the European Union) agreed to a 10% emissions increase for Iceland; but, since the EU's member states each have individual obligations,[83] much larger increases (up to 27%) are allowed for some of the less developed EU countries (see below Kyoto Protocol#Increase in greenhouse gas emission since 1990).[84] Reduction limitations expired in 2013.

Mechanism of compliance

The protocol defines a mechanism of "compliance" as a "monitoring compliance with the commitments and penalties for non-compliance."[85] According to Grubb (2003),[86] the explicit consequences of non-compliance of the treaty are weak compared to domestic law.[86] Yet, the compliance section of the treaty was highly contested in the Marrakesh Accords.[86]

Enforcement

If the enforcement branch determines that an Annex I country is not in compliance with its emissions limitation, then that country is required to make up the difference during the second commitment period plus an additional 30%. In addition, that country will be suspended from making transfers under an emissions trading program.[87]

Ratification process

The Protocol was adopted by COP 3 of UNFCCC on 11 December 1997 in Kyoto, Japan. It was opened on 16 March 1998 for signature during one year by parties to UNFCCC, when it was signed Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, the Maldives, Samoa, St. Lucia and Switzerland. At the end of the signature period, 82 countries and the European Community had signed. Ratification (which is required to become a party to the Protocol) started on 17 September with ratification of Fiji. Countries that did not sign acceded to the convention, which has the same legal effect.[1]

Article 25 of the Protocol specifies that the Protocol enters into force "on the ninetieth day after the date on which not less than 55 Parties to the Convention, incorporating Parties included in Annex I which accounted in total for at least 55% of the total carbon dioxide emissions for 1990 of the Annex I countries, have deposited their instruments of ratification, acceptance, approval or accession."[88]

The EU and its Member States ratified the Protocol in May 2002.[89] Of the two conditions, the "55 parties" clause was reached on 23 May 2002 when Iceland ratified the Protocol.[1] The ratification by Russia on 18 November 2004 satisfied the "55%" clause and brought the treaty into force, effective 16 February 2005, after the required lapse of 90 days.[90]

As of May 2013, 191 countries and one regional economic organization (the EC) have ratified the agreement, representing over 61.6% of the 1990 emissions from Annex I countries.[91] One of the 191 ratifying states—Canada—has renounced the protocol.

Non-ratification by the US

The US signed the Protocol on 12 November 1998,[92] during the Clinton presidency. To become binding in the US, however, the treaty had to be ratified by the Senate, which had already passed the 1997 non-binding Byrd-Hagel Resolution, expressing disapproval of any international agreement that did not require developing countries to make emission reductions and "would seriously harm the economy of the United States". The resolution passed 95-0.[93] Therefore, even though the Clinton administration signed the treaty,[94] it was never submitted to the Senate for ratification.

When George W. Bush was elected US president in 2000, he was asked by US Senator Chuck Hagel what his administration's position was on climate change. Bush replied that he took climate change "very seriously",[95] but that he opposed the Kyoto treaty because "it exempts 80% of the world, including major population centers such as China and India, from compliance, and would cause serious harm to the US economy."[96] The Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research reported in 2001:

This policy reversal received a massive wave of criticism that was quickly picked up by the international media. Environmental groups blasted the White House, while Europeans and Japanese alike expressed deep concern and regret. [...] Almost all world leaders (e.g. China, Japan, South Africa, Pacific Islands, etc.) expressed their disappointment at Bush's decision.

In response to this criticism, Bush stated: "I was responding to reality, and reality is the nation has got a real problem when it comes to energy." The Tyndall Centre called this "an overstatement used to cover up the big benefactors of this policy reversal, i.e., the US oil and coal industry, which has a powerful lobby with the administration and conservative Republican congressmen."[97]

As of 2016, the US is the only signatory that has not ratified the Protocol.[98] The US accounted for 36% of emissions in 1990. As such, for the treaty to go into legal effect without US ratification, it would require a coalition including the EU, Russia, Japan, and small parties. A deal, without the US Administration, was reached in the Bonn climate talks (COP-6.5), held in 2001.[99]

Withdrawal of Canada

In 2011, Canada, Japan and Russia stated that they would not take on further Kyoto targets.[100] The Canadian government announced its withdrawal—possible at any time three years after ratification—from the Kyoto Protocol on 12 December 2011, effective 15 December 2012.[101] Canada was committed to cutting its greenhouse emissions to 6% below 1990 levels by 2012, but in 2009 emissions were 17% higher than in 1990. The Harper government prioritized oil sands development in Alberta, and deprioritized improving the environment. Environment minister Peter Kent cited Canada's liability to "enormous financial penalties" under the treaty unless it withdrew.[100][102] He also suggested that the recently signed Durban agreement may provide an alternative way forward.[103] The Harper government claimed it would find a "Made in Canada" solution, but never found any such solution. Canada's decision received a generally negative response from representatives of other ratifying countries.[103]

Other states and territories where the treaty is not applicable

Andorra, Palestine, South Sudan, the United States and, following their withdrawal on 15 December 2012, Canada are the only UNFCCC Parties that are not party to the Protocol. Furthermore, the Protocol is not applied to UNFCCC observer the Holy See. Although the Kingdom of the Netherlands approved the protocol for the whole Kingdom, it did not deposit an instrument of ratification for Aruba, Curaçao, Sint Maarten or the Caribbean Netherlands.[104]

Government action and emissions

Annex I countries

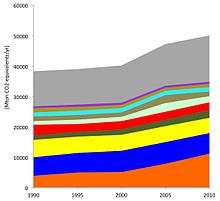

Total aggregate GHG emissions excluding emissions/removals from land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF, i.e., carbon storage in forests and soils) for all Annex I Parties (see list below) including the United States taken together decreased from 19.0 to 17.8 thousand teragrams (Tg, which is equal to 109 kg) CO

2 equivalent, a decline of 6.0% during the 1990-2008 period.[105]:3 Several factors have contributed to this decline.[105]:14 The first is due to the economic restructuring in the Annex I Economies in Transition[105]:14 (the EITs – see Intergovernmental Emissions Trading for the list of EITs). Over the period 1990-1999, emissions fell by 40% in the EITs following the collapse of central planning in the former Soviet Union and east European countries.[106]:25 This led to a massive contraction of their heavy industry-based economies, with associated reductions in their fossil fuel consumption and emissions.[45]:24

Emissions growth in Annex I Parties have also been limited due to policies and measures (PaMs).[105]:14 In particular, PaMs were strengthened after 2000, helping to enhance energy efficiency and develop renewable energy sources.[105]:14 Energy use also decreased during the economic crisis in 2007-2008.[105]:14

Projections

UNFCCC (2011)[105]:14 made projections of changes in emissions of the Annex I Parties and the effectiveness of their PaMs. It was noted that their projections should be interpreted with caution.[105]:7 For the 39 Annex I Parties, UNFCCC (2011) projected that existing PaMs would lead to annual emissions in 2010 of 17.5 thousand Tg CO

2 eq, excluding LULUCF, which is a decrease of 6.7% from the 1990 level.[105]:14 Annual emissions in 2020 excluding LULUCF were projected to reach 18.9 thousand Tg CO

2 eq, which is an increase of 0.6% on the 1990 level.[105]:14

UNFCCC (2011)[105]:14 made an estimate of the total effect of implemented and adopted PaMs. Projected savings were estimated relative to a reference (baseline) scenario where PaMs are not implemented. PaMs were projected to deliver emissions savings relative to baseline of about 1.5 thousand Tg CO

2 eq by 2010, and 2.8 thousand Tg CO

2 eq by 2020.[105]:14 In percentage terms, and using annual emissions in the year 1990 as a reference point, PaMs were projected to deliver at least a 5.0% reduction relative to baseline by 2010, and a 10.0% reduction relative to baseline in 2020.[105]:14 Scenarios reviewed by UNFCCC (2011)[105]:14 still suggested that total Annex I annual emissions would increase out to 2020 (see the preceding paragraph).

Annex I Parties with targets

| Country/region | Kyoto target 2008-2012 | Kyoto target 2013-2020 | GHG emissions 1990-2008 including LULUCF[108][109] | GHG emissions 1990-2008 excluding LULUCF[108][110] | CO2 emissions from fuel combustion only 1990-2009 [111][112] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | - | - | - | - | +20.4 |

| Canada[113][114] | -6 | - | +33.6 | +24.1 | +20.4 |

| Europe | -4.9 | ||||

| European Union | -8 | -20[115] | |||

| Austria | -8 (-13) | -20[115] | +6.6 | +10.8 | +12.2 |

| Belgium | -8 (-7.5) | -20[115] | -6.2 | -7.1 | -6.7 |

| Denmark | -8 (-21) | -20[115] | -6.8 | -6.8 | -7.2 |

| Finland | -8 (0) | -20[115] | -35.9 | -0.2 | +1.1 |

| France | -8 (0) | -20[115] | -12.7 | -5.9 | +0.6[116] |

| Germany | -8 (-21) | -20[115] | -17.6 | -21.4 | -21.1 |

| Greece | -8 (+25) | -20[115] | +22.9 | +23.1 | +28.6 |

| Iceland | +10 | -20[115] | +19.2 | +42.9 | +6.2 |

| Ireland | -8 (+13) | -20[115] | +19.9 | +23.2 | +32.4 |

| Italy | -8 (-6.5) | -20[115] | +0.4 | +4.7 | -2.0 |

| Luxembourg | -8 (-28) | -20[115] | -9.2 | -4.8 | -4.4 |

| Netherlands | -8 (-6) | -20[115] | -2.4 | -2.4 | +13.0 |

| Norway | +1 | -16 | -32.8 | +9.4 | +31.9 |

| Portugal | -8 (+27) | -20[115] | +18.3 | +32.2 | +35.3 |

| Spain | -8 (+15) | -20[115] | +44.0 | +42.5 | +37.7 |

| Sweden | -8 (+4) | -20[115] | +19.8 | -11.3 | -20.9 |

| Switzerland | -8 | -15.8 | +6.8 | +0.4 | +2.5 |

| United Kingdom | -8 (-12.5) | -19.0 | -18.5 | -15.2 | |

| Asia and Oceania | - | - | - | +12.7 | |

| Australia | +8 | -0.5 | +33.1 | +31.4 | +51.8 |

| Japan | -6 | - | -0.2 | +1.0 | +2.7 |

| New Zealand | 0 | - | +62.4 | +22.7 | +34.3 |

| Economies in Transition | - | - | - | -36.2 | |

| Bulgaria | -8 | -20[115] | -45.5 | -42.8 | -43.7 |

| Croatia | -5 | -20[115] | -13.7 | -0.9 | -8.4 |

| Czech Republic | -8 | -20[115] | -28.7 | -27.5 | -29.2 |

| Estonia | -8 | -20[115] | -69.9 | -50.9 | -59.4 |

| Hungary | -6 | -20[115] | -38.1 | -36.2 | -27.8 |

| Latvia | -8 | -20[115] | -307.9 | -55.6 | -63.8 |

| Lithuania | -8 | -20[115] | -69.1 | -51.8 | -62.6 |

| Poland | -6 | -20[115] | -34.4 | -29.6 | -16.2 |

| Romania | -8 | -20[115] | -53.5 | -45.9 | -53.1 |

| Russian Federation | 0 | - | -52.8 | -32.8 | -29.7 |

| Slovak Republic | -8 | -20[115] | -34.4 | -33.7 | -41.5 |

| Slovenia | -8 | -20[115] | +5.2 | +5.2 | +21.2 |

| Ukraine | 0 | -24 | -52.2 | -53.9 | -62.7 |

Data given in the table above may not be fully reflective of a country's progress towards meeting its first-round Kyoto target. The summary below contains more up-to-date information on how close countries are to meeting their first-round targets.

Collectively the group of industrialized countries committed to a Kyoto target, i.e., the Annex I countries excluding the US, have a target of reducing their GHG emissions by 4.2% on average for the period 2008-2012 relative to the base year, which in most cases is 1990.[106]:24 According to Olivier et al. (2011),[106]:24 the Kyoto Parties will comfortably exceed their collective target, with a projected average reduction of 16% for 2008-2012. This projection excludes both LULUCF and credits generated by the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM).[106]:24

As noted in the preceding section, between 1990–1999, there was a large reduction in the emissions of the EITs.[106]:25 The reduction in the EITs is largely responsible for the total (aggregate) reduction (excluding LULUCF) in emissions of the Annex I countries, excluding the US.[106]:25 Emissions of the Annex II countries (Annex I minus the EIT countries) have experienced a limited increase in emissions from 1990–2006, followed by stabilization and a more marked decrease from 2007 onwards.[106]:25 The emissions reductions in the early nineties by the 12 EIT countries who have since joined the EU, assist the present EU-27 in meeting its collective Kyoto target.[106]:25

Almost all European countries are on track to achieve their first-round Kyoto targets.[117] Spain plans to meet its target by purchasing a large quantity of Kyoto units through the flexibility mechanisms.[117] Australia,[106]:25 Canada[106]:25 (Canada withdrew from the Kyoto treaty in 2012),[118] and Italy[117] are not on course to meet their first-round Kyoto targets. In order to meet their targets, these countries would need to purchase emissions credits from other Kyoto countries.[106]:25 As noted in the section on Intergovernmental Emissions Trading, purchasing surplus credits from the EIT countries would not actually result in total emissions being reduced. An alternative would be the purchase of CDM credits or the use of the voluntary Green Investment Scheme.

In December 2011, Canada's environment minister, Peter Kent, formally announced that Canada would withdraw from the Kyoto accord a day after the end of the 2011 United Nations Climate Change Conference (see the section on the withdrawal of Canada).[118]

Annex I Parties without Kyoto targets

Belarus, Malta, and Turkey are Annex I Parties but do not have first-round Kyoto targets.[119] The US has a Kyoto target of a 6% reduction relative to the 1990 level, but has not ratified the treaty.[106]:25 Emissions in the US have increased 11% since 1990, and according to Olivier et al. (2011),[106]:25 it will be unable to meet its original Kyoto target.

If the US had ratified the Kyoto Protocol, the average percentage reduction in total GHG emissions for the Annex I group would have been a 5.2% reduction relative to the base year.[106]:26 Including the US in their calculation, Olivier et al. (2011)[106]:26 projected that the Annex I countries would collectively achieve a 7% reduction relative to the base year, which is lower than the original target of a 5.2% reduction. This projection excludes expected purchases of emissions credits.[106]:26

Non-Annex I

UNFCCC (2005) compiled and synthesized information reported to it by non-Annex I Parties.[32] Most non-Annex I Parties belonged in the low-income group, with very few classified as middle-income.[32]:4 Most Parties included information on policies relating to sustainable development. Sustainable development priorities mentioned by non-Annex I Parties included poverty alleviation and access to basic education and health care.[32]:6 Many non-Annex I Parties are making efforts to amend and update their environmental legislation to include global concerns such as climate change.[32]:7

A few Parties, e.g., South Africa and Iran, stated their concern over how efforts to reduce emissions by Annex I Parties could adversely affect their economies.[32]:7 The economies of these countries are highly dependent on income generated from the production, processing, and export of fossil fuels.

Emissions

GHG emissions, excluding land use change and forestry (LUCF), reported by 122 non-Annex I Parties for the year 1994 or the closest year reported, totalled 11.7 billion tonnes (billion = 1,000,000,000) of CO2-eq. CO2 was the largest proportion of emissions (63%), followed by methane (26%) and nitrous oxide (N2O) (11%).

The energy sector was the largest source of emissions for 70 Parties, whereas for 45 Parties the agriculture sector was the largest. Per capita emissions (in tonnes of CO2-eq, excluding LUCF) averaged 2.8 tonnes for the 122 non-Annex I Parties.

- The Africa region's aggregate emissions were 1.6 billion tonnes, with per capita emissions of 2.4 tonnes.

- The Asia and Pacific region's aggregate emissions were 7.9 billion tonnes, with per capita emissions of 2.6 tonnes.

- The Latin America and Caribbean region's aggregate emissions were 2 billion tonnes, with per capita emissions of 4.6 tonnes.

- The "other" region includes Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Malta, Moldova, and Macedonia. Their aggregate emissions were 0.1 billion tonnes, with per capita emissions of 5.1 tonnes.

Parties reported a high level of uncertainty in LUCF emissions, but in aggregate, there appeared to only be a small difference of 1.7% with and without LUCF. With LUCF, emissions were 11.9 billion tonnes, without LUCF, total aggregate emissions were 11.7 billion tonnes.

Trends

In several large developing countries and fast growing economies (China, India, Thailand, Indonesia, Egypt, and Iran) GHG emissions have increased rapidly (PBL, 2009).[120] For example, emissions in China have risen strongly over the 1990–2005 period, often by more than 10% year. Emissions per-capita in non-Annex I countries are still, for the most part, much lower than in industrialized countries. Non-Annex I countries do not have quantitative emission reduction commitments, but they are committed to mitigation actions. China, for example, has had a national policy programme to reduce emissions growth, which included the closure of old, less efficient coal-fired power plants.

Cost estimates

Barker et al. (2007, p. 79) assessed the literature on cost estimates for the Kyoto Protocol.[121] Due to non-US participation in the Kyoto treaty, costs estimates were found to be much lower than those estimated in the previous IPCC Third Assessment Report. Without US participation, and with full use of the Kyoto flexible mechanisms, costs were estimated at less than 0.05% of Annex B GDP. This compared to earlier estimates of 0.1–1.1%. Without use of the flexible mechanisms, costs without US participation were estimated at less than 0.1%. This compared to earlier estimates of 0.2–2%. These cost estimates were viewed as being based on much evidence and high agreement in the literature.

Views on the Protocol

Gupta et al. (2007) assessed the literature on climate change policy. They found that no authoritative assessments of the UNFCCC or its Protocol asserted that these agreements had, or will, succeed in solving the climate problem.[20] In these assessments, it was assumed that the UNFCCC or its Protocol would not be changed. The Framework Convention and its Protocol include provisions for future policy actions to be taken.

Gupta et al. (2007)[122] described the Kyoto first-round commitments as "modest," stating that they acted as a constraint on the treaty's effectiveness. It was suggested that subsequent Kyoto commitments could be made more effective with measures aimed at achieving deeper cuts in emissions, as well as having policies applied to a larger share of global emissions.[122] In 2008, countries with a Kyoto cap made up less than one-third of annual global carbon dioxide emissions from fuel combustion.[123]

World Bank (2010)[124] commented on how the Kyoto Protocol had only had a slight effect on curbing global emissions growth. The treaty was negotiated in 1997, but in 2006, energy-related carbon dioxide emissions had grown by 24%.[125] World Bank (2010) also stated that the treaty had provided only limited financial support to developing countries to assist them in reducing their emissions and adapting to climate change.[124]

Some of the criticism of the Protocol has been based on the idea of climate justice (Liverman, 2008, p. 14).[28]

This has particularly centered on the balance between the low emissions and high vulnerability of the developing world to climate change, compared to high emissions in the developed world. Another criticism of the Kyoto Protocol and other international conventions, is the right of indigenous peoples right to participate. Quoted here from The Declaration of the First International Forum of Indigenous Peoples on Climate Change, it says "Despite the recognition of our role in preventing global warming, when it comes time to sign international conventions like the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, once again, our right to participate in national and international discussions that directly affect or Peoples and territories is denied."[126] Additionally, later in the declaration, it reads

"We denounce the fact that neither the [United Nations] nor the Kyoto Protocol recognizes the existence or the contributions of Indigenous Peoples. Furthermore, the debates under these instruments have not considered the suggestions and proposals of the Indigenous Peoples nor have the appropriate mechanisms to guarantee our participation in all the debates that directly concern the Indigenous Peoples has been established."[126]

Some environmentalists have supported the Kyoto Protocol because it is "the only game in town," and possibly because they expect that future emission reduction commitments may demand more stringent emission reductions (Aldy et al.., 2003, p. 9).[127] In 2001, seventeen national science academies stated that ratification of the Protocol represented a "small but essential first step towards stabilising atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases."[128] Some environmentalists and scientists have criticized the existing commitments for being too weak (Grubb, 2000, p. 5).[129]

The United States (under former President George W. Bush) and Australia (initially, under former Prime Minister John Howard) did not ratify the Kyoto treaty.[130] According to Stern (2006),[130] their decision was based on the lack of quantitative emission commitments for emerging economies (see also the 2000 onwards section). Australia, under former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, has since ratified the treaty,[131][132] which took effect in March 2008.[133]

Views on the flexibility mechanisms

Another area which has been commented on is the role of the Kyoto flexibility mechanisms – emissions trading, Joint Implementation, and the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM).[134][135] The flexibility mechanisms have attracted both positive and negative comments.[136][137][138]

As mentioned earlier, a number of Annex I Parties have implemented emissions trading schemes (ETSs) as part of efforts to meet their Kyoto commitments. General commentaries on emissions trading are contained in emissions trading and carbon emission trading. Individual articles on the ETSs contain commentaries on these schemes (see Kyoto Protocol#International Emissions Trading for a list of ETSs).

One of the arguments made in favour of the flexibility mechanisms is that they can reduce the costs incurred by Annex I Parties in meeting their Kyoto commitments.[134] Criticisms of flexibility have, for example, included the ineffectiveness of emissions trading in promoting investment in non-fossil energy sources,[139] and adverse impacts of CDM projects on local communities in developing countries.[140]

Philosophy

As the Kyoto Protocol seeks to reduce environmental pollutants while at the same time altering the freedoms of some citizens.

As discussed by Milton Friedman, one can achieve both economic and political freedom through capitalism; nonetheless, it is never guaranteed that one is going to have equality of wealth of those on top of the “food chain” of this capitalistic world.[141] All these alterations come to what the leaders of the citizens choose to impose in means of improving ones lifestyle. In the case of the Kyoto Protocol, it seeks to impose regulations that will reduce production of pollutants towards the environment. Furthermore, seeking to compromise the freedoms of both private and public citizens. In one side it imposes bigger regulations towards companies and reducing their profits as they need to fulfill such regulations with, which are oftentimes more expensive, alternatives for production. On the other hand, it seeks to reduce the emissions that potentially cause the rapid environmental change called climate change.

The conditions of the Kyoto Protocol consist of mandatory targets on greenhouse gas emissions for the world's leading economies. As provided by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, "These targets range from -8 per cent to +10 per cent of the countries' individual 1990 emissions levels with a view to reducing their overall emissions of such gases by at least 5 per cent below existing 1990 levels in the commitment period 2008 to 2012." [142]

These goals are challenged, however, by climate change deniers, who condemn strong scientific evidence of the human impact on climate change. One prominent scholar opines that these climate change deniers "arguably" breach Rousseau's notion of the social contract, which is an implicit agreement among the members of a society to coordinate efforts in the name of overall social benefit. The climate change denial movement hinders efforts at coming to agreements as a collective global society on climate change.[143]

Conference of the Parties

The official meeting of all states party to the Kyoto Protocol is the Conference of the Parties. It is held every year as part of the United Nations Climate Change conference, which also serves as the formal meeting of UNFCCC. The first Meetings of Parties of the Kyoto Protocol (CMP) was held in 2005 in conjunction with the eleventh Conferences of parties to UNFCCC (COP). Also parties to the Convention that are not parties to the Protocol can participate in Protocol-related meetings as observers. The first conference was held in 1995 in Berlin, while the 2013 conference was held in Warsaw. Later COPs were held in Lima, Peru in 2014 and in Paris, France in 2015.

Amendment and possible successors

In the non-binding "Washington Declaration" agreed on 16 February 2007, heads of governments from Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States, Brazil, China, India, Mexico and South Africa agreed in principle on the outline of a successor to the Kyoto Protocol. They envisaged a global cap-and-trade system that would apply to both industrialized nations and developing countries, and initially hoped that it would be in place by 2009.[144][145]

The United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen in December 2009 was one of the annual series of UN meetings that followed the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio. In 1997 the talks led to the Kyoto Protocol, and the conference in Copenhagen was considered to be the opportunity to agree a successor to Kyoto that would bring about meaningful carbon cuts.[146][147]

The 2010 Cancún agreements include voluntary pledges made by 76 developed and developing countries to control their emissions of greenhouse gases.[148] In 2010, these 76 countries were collectively responsible for 85% of annual global emissions.[148][149]

By May 2012, the US, Japan, Russia, and Canada had indicated they would not sign up to a second Kyoto commitment period.[150] In November 2012, Australia confirmed it would participate in a second commitment period under the Kyoto Protocol and New Zealand confirmed that it would not.[151]

New Zealand's climate minister Tim Groser said the 15-year-old Kyoto Protocol was outdated, and that New Zealand was "ahead of the curve" in looking for a replacement that would include developing nations.[152] Non-profit environmental organisations such as the World Wildlife Fund criticised New Zealand's decision to pull out.[153]

On 8 December 2012, at the end of the 2012 United Nations Climate Change Conference, an agreement was reached to extend the Protocol to 2020 and to set a date of 2015 for the development of a successor document, to be implemented from 2020 (see lede for more information).[154] The outcome of the Doha talks has received a mixed response, with small island states critical of the overall package.The Kyoto second commitment period applies to about 11% of annual global emissions of greenhouse gases. Other results of the conference include a timetable for a global agreement to be adopted by 2015 which includes all countries.[155] At the Doha meeting of the parties to the UNFCCC on 8 December 2012, the European Union chief climate negotiator, Artur Runge-Metzger, pledged to extend the treaty, binding on the 27 European Member States, up to the year 2020 pending an internal ratification procedure.

Ban Ki Moon, Secretary General of the United Nations, called on world leaders to come to an agreement on halting global warming during the 69th Session of the UN General Assembly[156] on 23 September 2014 in New York. UN member states have been negotiating a future climate deal over the last five years. A preliminary calendar was adopted to confirm "national contributions" to the reduction of CO2 emissions by 2015 before the UN climate summit which was held in Paris at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference.

See also

- Alternatives to the Kyoto Protocol and successor

- Asia Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate

- Business action on climate change

- Carbon emission trading

- Carbon footprint

- Clean Development Mechanism

- Climate legislation

- Copenhagen Accord

- Environmental agreements

- Environmental impact of aviation

- Environmental law

- Environmental tariff

- List of climate change initiatives

- List of international environmental agreements

- Low-carbon economy

- Montreal Protocol

- Net Capacity Factor

- Paris Agreement

- Politics of global warming

- Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation or REDD

- Sustainability

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change or UNFCCC

- World People's Conference on Climate Change

- Action for climate empowerment (ACE)

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Status of ratification". UNFCC Homepage. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ↑ http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpeng.pdf

- ↑ http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/status_of_ratification/items/2613.php

- 1 2 "7 .a Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change". UN Treaty Database. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ↑ "7 .c Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol". UN Treaty Database. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Annex B". United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. n.d. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- ↑ KOM(2007) final edition page 2

- ↑ Figueres, C. (15 December 2012), "Environmental issues: Time to abandon blame-games and become proactive - Economic Times", The Economic Times / Indiatimes.com, Times Internet, retrieved 2012-12-18

- ↑ "United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change". United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ↑ US National Research Council (2001). "Summary". Climate Change Science: An Analysis of Some Key Questions. Washington, D.C., U.S.A.: National Academy Press. p. 3.

- 1 2 US National Research Council (2008). Understanding and Responding to Climate Change (PDF). Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate, US National Academy of Sciences. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 IPCC (2007). "3. Projected climate change and its impacts". In Core Writing Team (eds.); et al. Summary for Policymakers. Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Temperatures are measured relative to the average global temperature averaged over the years 1980-1999, with the projected change averaged over 2090–2099.

- 1 2 3 Karl, T.R.; et al., eds. (2009). "Global climate change". Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States. 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-14407-0.

- ↑ http://www.ec.gc.ca/Publications/default.asp?lang=En&n=EE4F06AE-1&xml=EE4F06AE-13EF-453B-B633-FCB3BAECEB4F&offset=3&toc=show Canadian government official archives

- ↑ United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (2011a), Status of Ratification of the Convention, UNFCCC Secretariat: Bonn, Germany: UNFCCC. Most countries in the world are Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which has adopted the 2 °C target. There are currently (as of November 25, 2011) 195 Parties (194 states and 1 regional economic integration organization (the European Union)) to the UNFCCC.

- 1 2 3 4 IPCC (2001d). "Question 1". In Watson, R.T.; the Core Writing Team. Climate Change 2001: Synthesis Report. A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Granger Morgan *, M.; Dowlatabadi, H.; Henrion, M.; Keith, D.; Lempert, R.; McBride, S.; Small, M.; Wilbanks, T. (2009). "BOX NT.1 Summary of Climate Change Basics". Non-Technical Summary. Synthesis and Assessment Product 5.2: Best practice approaches for characterizing, communicating, and incorporating scientific uncertainty in decision making. A Report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research. Washington D.C., USA.: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 11.

(* is Lead Author)

- 1 2 Grubb, M. (2004). "Kyoto and the Future of International Climate Change Responses: From Here to Where?" (PDF). International Review for Environmental Strategies. 5 (1): 2 (PDF version).

- 1 2 3 Gupta, S.; et al. (2007). "13.3.1 Evaluations of existing climate change agreements. In (book chapter): Policies, instruments, and co-operative arrangements.". In B. Metz; et al. Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y., U.S.A.. This version: IPCC website. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Grubb & Depledge 2001, p. 269

- ↑ "Article 2". The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Archived from the original on October 28, 2005. Retrieved November 15, 2005.

Such a level should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner

- 1 2 7.32 "Question 7" Check

|chapter-url=value (help), Stabilizing atmospheric concentrations would depend upon emissions reductions beyond those agreed to in the Kyoto Protocol , p.122, in IPCC TAR SYR 2001 - 1 2 Meehl, G. A.; et al. (2007). "FAQ 10.3 If Emissions of Greenhouse Gases are Reduced, How Quickly do Their Concentrations in the Atmosphere Decrease?". In Solomon, S.; et al. Global Climate Projections. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2007). "Human and Natural Drivers of Climate Change". In Solomon, S.; et al. Summary for Policymakers. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC. Cambridge University Press.

- 1 2 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (2011), Kyoto Protocol, UNFCCC

- ↑ Depledge, J. (August 1999 – August 2000), United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Technical paper: Tracing the Origins of the Kyoto Protocol: An Article-by-Article Textual History (PDF), UNFCCC, p. 6

- 1 2 Liverman, D. M. (2008). "Conventions of climate change: constructions of danger and the dispossession of the atmosphere" (PDF). Journal of Historical Geography. 35 (2): 279–296. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2008.08.008. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ↑ Grubb 2003, p. 147

- ↑ The benchmark 1990 emission levels accepted by the Conference of the parties of UNFCCC (decision 2/CP.3) were the values of "global warming potential" calculated for the IPCC Second Assessment Report. These figures are used for converting the various greenhouse gas emissions into comparable carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2-eq) when computing overall sources and sinks. Source: "Methodological issues related to the Kyoto protocol" (PDF). Report of the Conference of the Parties on its third session, held at Kyoto from 1 to 11 December 1997, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 25 March 1998. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ↑ "Industrialized countries to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 5.2%" (Press release). United Nations Environment Programme. 11 December 1997. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 UNFCCC (25 October 2005), Sixth compilation and synthesis of initial national communications from Parties not included in Annex I to the Convention. Note by the secretariat. Executive summary. Document code FCCC/SBI/2005/18, United Nations Office at Geneva, Switzerland, retrieved 20 May 2010

- 1 2 3 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (2011), Kyoto Protocol, UNFCCC

- ↑ Adam, David (2 December 2007), "UK to seek pact on shipping and aviation pollution at climate talks", The Guardian

- ↑ United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (2011), Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, UNFCCC

- ↑ European Environment Agency (EEA) (15 November 2005), Kyoto burden-sharing targets for EU-15 countries - EEA, EEA

- 1 2 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (2008), Kyoto Protocol Reference Manual On Accounting of Emissions and Assigned Amount (PDF), Bonn, Germany: Climate Change Secretariat (UNFCCC), p. 55, ISBN 92-9219-055-5

- ↑ Bashmakov, I.; et al., "6. Policies, Measures, and Instruments", Executive summary, in IPCC TAR WG3 2001

- ↑ Clifford Chance LLP (2012). "Clean Development Mechanism: CDM and the UNFCC" http://a4id.org/sites/default/files/user/CDM%26UNFCCCcorrected.pdf . Advocates for International Development. Retrieved: 19 September 2013.

- 1 2 Toth, F. L.; et al., "10. Decision-making Frameworks", 10.4.4. Where Should the Response Take Place? The Relationship between Domestic Mitigation and the Use of International Mechanisms, in IPCC TAR WG3 2001

- ↑ Bashmakov, I.; et al., "6. Policies, Measures, and Instruments", 6.3 International Policies, Measures, and Instruments, in IPCC TAR WG3 2001

- 1 2 Hourcade, J.-C.; et al., "8. Global, Regional, and National Costs and Ancillary Benefits of Mitigation", 8.3.1 International Emissions Quota Trading Regimes, in IPCC TAR WG3 2001

- ↑ Bashmakov, I.; et al., "6. Policies, Measures, and Instruments", 6.3.2 Project-based Mechanisms (Joint Implementation and the Clean Development Mechanism), in IPCC TAR WG3 2001

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Hood, C. (November 2010). "5. Current and proposed emissions trading systems" (PDF). Review Existing and Proposed Emissions Trading Systems: Information paper. Head of Publications Service, 9 rue de la Fédération, 75739 Paris Cedex 15, France: International Energy Agency (IEA). Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Carbon Trust (March 2009). "Global Carbon Mechanisms: Emerging lessons and implications (CTC748)". Carbon Trust website. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ↑ World Bank (2008), Development and Climate Change: A Strategic Framework for the World Bank Group: Technical Report, Washington, DC, USA: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank.

- ↑ Hourcade, J.-C.; et al. (2001). "8.3.1.1 "Where Flexibility"". In B. Metz; et al. 8. Global, Regional, and National Costs and Ancillary Benefits of Mitigation. Climate Change 2001: Mitigation. A Contribution of Working Group III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. p. 538.

- ↑ Blyth, W.; Baron, R. (2003), Green Investment Schemes: Options and Issues (PDF), Paris, France: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Environment Directorate and International Energy Agency (IEA), p. 11 OECD reference: COM/ENV/EPOC/IEA/SLT(2003)9

- ↑ Chiavari, J.; Pallemaerts, M. (30 June 2008), Energy and Climate Change in Russia (note requested by the European Parliament's temporary committee on Climate Change, Policy Department Economy and Science, DG Internal Policies, European Parliament) (PDF), Brussels, Belgium: Institute for European Environmental Policy, p. 11

- 1 2 Carbon Finance at the World Bank (2011), Carbon Finance - Glossary of Terms: Definition of "Green Investment Scheme" (GIS), Washington, D.C., U.S.A.: World Bank Carbon Finance Unit (CFU), retrieved 15 December 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 World Bank (2011), State and Trends of the Carbon Market Report 2011 (PDF), Washington, DC, USA: World Bank Environment Department, Carbon Finance Unit

- ↑ Government of Japan (28 March 2008), Kyoto Protocol Target Achievement Plan (Provisional Translation) (PDF), Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of the Environment, Government of Japan, pp. 81–82

- ↑ Ramming, I.; et al. (September 2008). "34. AAU Trading and the Impact on Kyoto and EU Emissions Trading. Before the Flood or Storm in a Tea-cup?". In Carnahan, K. Greenhouse Gas Market Report 2008. Geneva, Switzerland: International Emissions Trading Association (IETA). p. 141. This document can also be downloaded as a PDF file

- ↑ World Bank (2010). "World Development Report 2010: Development and Climate Change". The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- 1 2 "Chapter 8 The challenge of stabilisation", Box 8.1 Likelihood of exceeding a temperature increase at equilibrium (PDF), p. 195, in Stern 2006

- 1 2 Fisher, B.; et al., "Chapter 3: Issues related to mitigation in the long-term context", 3.3.5.1 Emission reductions and timing , in IPCC AR4 WG3 2007

- ↑ Fisher, B.; et al., "Chapter 3: Issues related to mitigation in the long-term context", 3.3.2 Definition of a stabilization target , in IPCC AR4 WG3 2007

- 1 2 "Synthesis report", 5.4 Emission trajectories for stabilisation , in IPCC AR4 SYR 2007

- 1 2 "Chapter 8 The challenge of stabilisation", Sec 8.5 Pathways to stabilisation (PDF), in Stern 2006, p. 199

- ↑ Höhne, N., Impact of the Kyoto Protocol on Stabilization of Carbon Dioxide Concentration (PDF), Cologne, Germany: ECOFYS energy & environment

- ↑ United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (2011), Conference of the Parties - Sixteenth Session: Decision 1/CP.16: The Cancun Agreements: Outcome of the work of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action under the Convention (English): Paragraph 4 (PDF), Bonn, Germany: UNFCCC Secretariat, p. 3

- ↑ International Energy Agency (IEA) (2010), "13. Energy and the ultimate climate change target" (PDF), World Energy Outlook 2010, Paris, France: IEA, p. 380, ISBN 978-92-64-08624-1

- ↑ Levin, K.; Bradley, R. (February 2010), Working Paper: Comparability of Annex I Emission Reduction Pledges (PDF), Washington DC, USA: World Resources Institute, p. 16

- 1 2 3 4 Gupta, S.; et al., "Chapter 13: Policies, instruments, and co-operative arrangements", Box 13.7 The range of the difference between emissions in 1990 and emission allowances in 2020/2050 for various GHG concentration levels for Annex I and non-Annex I countries as a group , in IPCC AR4 WG3 2007

- ↑ King, D.; et al. (July 2011), "Copenhagen and Cancun", International climate change negotiations: Key lessons and next steps, Oxford, UK: Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford, p. 14, doi:10.4210/ssee.pbs.2011.0003, archived from the original on 1 August 2013 PDF version is also available Archived 13 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Dessai 2001, p. 3

- ↑ Baede, A.P.M. (ed.), "Annex II", Glossary: Land use and Land-use change, in IPCC AR4 SYR 2007