Kwakwaka'wakw art

Kwakwaka'wakw art describes the art of the Kwakwaka'wakw peoples of British Columbia. It encompasses a wide variety of woodcarving, sculpture, painting, weaving and dance. Kwakwaka'wakw arts are exemplified in totem poles, masks, wooden carvings, jewelry and woven blankets. Visual arts are defined by simplicity, realism, and artistic emphasis. Dances are observed in the many rituals and ceremonies in Kwakwaka'wakw culture. Much of what is known about Kwakwaka'wakw art comes from oral history, archeological finds in the 19th century, inherited objects, and devoted artists educated in Kwakwaka'wakw traditions.

Artists

The learning of a craft is central to the education of young tribe members. Youths are encouraged to engage in craft work, and are apprenticed to more experienced experts.[1] Some are employed by local chiefs as personal carvers, who are then tasked to produce wooden gifts bearing the house symbols to distribute in potlatch.[2] Wealth from trade resulted in a Golden Age of potlatch art in the late 19th century,[3] but to curb this perceived extravagance, the Canadian government outlawed the potlatch and other ceremonies with the Canadian Indian Act of 1884,[4] which contributed to a decline in artistic production, some say. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, several artists earned their living as carvers in the manner described above, since their work was commissioned by their villages. Once the shock of those participants in the Cranmer potlatch in 1921 wore off and governments were realizing native populations were no longer on the decline, art as a means of earning a living was encouraged - as it had begun to be in Alaska. Some carvers with standing and longevity, and some apprenticed to them later stepped forward to participate in the revival of Kwakwaka'wakw art, including sculptors Dan Cranmer, Chief Willie Seaweed (1873–1967),[5] Charlie James, Chief Mungo Martin[6] (1879–1962) and his wife Abayah's greatgrandsons Tony Hunt (b. 1942) and Richard Hunt (b. 1951). Mary Ebbets Hunt and Abayah Martin, Mungo Martin's wife,[6] were both important artists who produced many woven pieces. Traditionally, women were weavers, but Ellen Neel (1916–1966), Martin's niece, went on to become a noted carver.[7]

Style

The art of the Kwakwaka'wakw peoples is similar to other styles in the realm of Northwest coast art, but with significant differences. Kwakwaka'wakw art can be defined by deep cuts into the wood, and a minimal use of paint reserved for emphasis purposes. Like other forms of Northwest coast art, Kwakwaka'wakw art employs "punning" or "kenning", a style that fills visual voids with independent figures and motifs[8] - for example: a face painted in a whale fin.

Materials

The materials used in Kwakwaka'wakw art include wood, horn, bark, shell, animal bone and various pigments. For wood, western red cedar (Thuja plicata) is preferred for large projects, as it grows in abundance along the Northwest coast. Yellow cedar (Callitropsis nootkatensis) was used for smaller objects. The wood is sometimes oiled for smaller carvings. Wood was steamed to make it more pliable. Horn is used to create tools, usually cooking utensils. To do this, the horn is softened by boiling, then bent and carved into the desired shape. For paint, red ochre is used, along with white paste from burnt clamshells and many others.[9]

Tools

Traditionally, tools have been made by the artisans themselves for personal use. Tools include adzes, carving knives, stone axes, stone hammers and paintbrushes. Brushes were sometimes made from porcupine hair.[9] Later, the loom was used to weave blankets and curtains. Some tools were ceremonial, and thus decorated with carvings.

Crafts

The crafts of the Kwakwaka'wakw are made out of extensive woodwork, and include a wide variety of objects, from masks, effigies, rattles, storage boxes, food vessels to large totems and house posts. Virtually all crafts are painted to some extent.

Masks

Masks were a vital part of Kwakwaka'wakw art and culture. The mask was crucial in dances in order to portray the character conveyed by the dancer. As such, a wide array of masks exist, depicting mythological beings, animals, forces of nature, and other humans. Some masks are decorated with feathers and "hair", usually represented by animal fur or strips of cedar bark. The following are a select few important types of masks:

._Thunderbird_Transformation_Mask%2C_19th_century.jpg)

- Hamatsa ("Raven-cannibal") masks are large pieces carved in the form of a raven,[10] with an elongated or curved beak. "Multiple" masks also exist, where two or more raven heads are used in the same mask. Cedar bark is commonly used to form a "mane" around hamatsa masks.

- Tsonokwa or Dzunuk'wa ("Wild Woman of the Woods" or "Giant" or "Giantess") are made with wild, unkempt hair and distinctly protruding lips. She had wide eyes, facial hair, and sunken cheeks.[11]

- Komokwa ("Wealthy one", "Chief of the Sea") masks are crafted to represent the sea. Features include fish-like eyes, gill slits, scales, and occasionally an ornamental seabird crest. Round holes or painted circles can be found around the nose and cheek, and have been interpreted as air bubbles, octopus tentacle suckers, or anemones.[12]

- Bookwus ("Wild man of the woods") masks are carved with deep inset eyes, a hooked nose, and features similar to those of a human skull. The bookwus (also bukwús or bookwuu) lives near streams or forests' edges and collects the souls of drowning victims. His masks are usually green, brown, or black.[13]

- Noohlmahl or Nulamal ("Fool") masks depict violent buffoons sent by the hamatsa. They are easily distinguished by an exaggerated nose flowing with mucus, and a humorous twisted expression.[14]

- "Sun" masks were usually round, with a hawk-like figure in the middle. Pieces of wood emanating from the edges symbolize the sun's rays. Sun masks are usually painted white, orange and red. Flattened copper is sometimes used on the mask's face.[15]

- "Moon" masks tend to depict a young male with features of a raven, such as feathers or a beak. Masks exist for both full and crescent moons. To do this, masks are sometimes completely round, round with painted crescent, or simply a mask with a moon figurehead crest.[15]

- "Echo" masks symbolize speech and ventriloquism. These masks are distinguished by a set of interchangeable mouthpieces, each a detachable carving itself. The pieces are inserted into the lip region of the mask body, and each represents a being with a different voice.[15]

- Transformation masks are complex, intricately built masks designed to depict the dual nature of mythological beings. The Kwakwaka'wakw carried this art to its highest form.[16] The masks are used in dances, where the dancer may "open" the mask via a series of strings in order to reveal a second figure, usually a "human" mask concealed within an animal exterior. Transformation masks are constructed from several sections, the outer sections come together to form the animal or mythological form, which then split to the sides to reveal the interior mask.[16]

Jewelry and metalwork

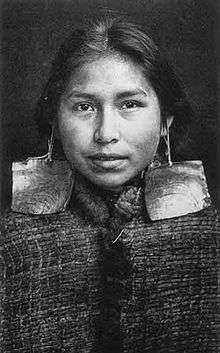

Jewelry amongst the Kwakwaka'wakw consisted of earrings, bracelets, necklaces, nose rings, lip piercings and more. Abalone shells, stone, ivory and wood were used in jewelry making. Contact with European settlers brought gold and silver, which were hammered into desired shapes. Silver and gold jewelry were often inscribed in patterns and mythological figures.[17] Wooden hairpins have also been found.

Copper in varying sizes was worn on the clothing of high-ranking individuals. Copper is also the term for beaten copper objects, often engraved and shaped like a "T" or a shield. These coppers symbolize great wealth and can be broken into pieces to give away at potlatches. Representations of shield-shaped coppers can be found on Kwakwaka'wakw poles.[18]

Textiles

Textile arts in Kwakwaka'wakw culture are represented by ceremonial curtains, dance aprons, blankets and clothing. Weaving is most often done by women.

The ceremonial curtain, or mawihl, is a painted curtain hung over the entrance to the dressing room used in dance ceremonies. Dancers could disappear behind the curtain as the scene demanded or to change their costumes. The mawihl was typically made from cotton, and painted with the spirit of the dancing house.[19]

The chilkat blanket was adopted by the Kwakwaka'wakw from the Tlingit and Tsimshian peoples to the north. These blankets are woven on a loom from shredded cedar bark and the wool of mountain goats.[20] Chilkat blankets are heavy and extremely ornate; each taking almost a year to complete. As such, the blankets are highly valued amongst the Northwest coast peoples. The design has traditionally been first painted by a man, and then woven by a woman in accordance with the design.[21] Designs are usually patterned and elaborate, showing a mosaic of ancestors and mythological figures. The fringes of the chilkat blanket are left with flowing threads of wool. A prominent weaver of chilkat blankets was Mary Ebbets Hunt. Hunt was a Tlingit woman who married an Englishman working in the Fort Rupert area, part of Kwakwaka'wakw territory. She had learned to weave from the northern tribes, and despite her reluctance to demonstrate her craft in front of Kwakwaka'wakw women, this technique was eventually passed on to the Kwakwaka'wakw.[21]

Button blankets become prevalent with the advent of the blanket trade. Button blankets or cloaks are brightly colored, usually with a navy blue base and red appliqué of Melton wool. Borders and a central motif, usually a family crest, are decorated with abalone or mother-of-pearl buttons.[21][22]

Dance aprons and leggings were also worn during ceremonies. The aprons were often decorated with trinkets such as small coppers, puffin beaks, deer hoofs, etc., which produced pleasing sounds while dancing.[21]

Totem and house poles

_a_Kwakwaka'wakw_big_house.jpg)

The totem pole is arguably the most complex and grandiose art form in Kwakwaka'wakw culture. Poles are placed outside family houses where they display the family's crests, history, wealth, social rank, inheritance, and privilege.[23] The sequence of characters and symbols sculpted into a totem pole is indicative of past family events, ancestors, myths, and heraldic crests, with the bottom figure usually being the most prominent.[24] The interpretation of the symbols is retold in a semi-legendary form when the pole is first dedicated to a certain house after completion. Kwakwaka'wakw totems are built from red cedar and can range between fifteen and fifty feet tall. The reputation of a pole's maker depended on the quality of his work. The Kwakwaka'wakw style of totem uses more protruding elements than other Northwest coast totems, such as stretching limbs, beaks jutting out, and wings thrust away from the body of the pole.[25] Painting followed a scheme of alternating dark and light colors for contrast. Finally, like other forms of Kwakwaka'wakw art, Kwakwaka'wakw totems display a high emphasis on realism.[25]

House poles are posts supporting the homes of important tribal members. They are commissioned by the future homeowner and built by carvers of the tribe. Kwakwaka'wakw poles are noticeably simpler and bolder in construction, and tend to be thicker and well rounded.[26] House posts depict ancestors, house symbols, and animals such as the sea lion and grizzly bear. A frontal "entrance" pole may be used, and is differentiated by the long opening at the bottom of the pole, and the fact that they are not supporting any part of the roof.[26]

Trinkets and others

A large variety of smaller wooden objects were carved by the Kwakwaka'wakw. These included whistles, rattles, kerfed boxes, effigies, staffs, utensils, ceremonial knives, headdresses, headbands and food vessels.

Painting and graphic art

Painting was traditionally used to decorate carvings and flat surfaces. Drafts for totems, masks and textiles were the first type of Kwakwaka'wakw painting. With the introduction of paper, artists branched into graphic art and produced many notable paintings. Later, local research organizations commissioned artists such as Ray Hanuse to paint interiors and exteriors with Kwakwaka'wakw motifs.[27]

Dance

Like other dancing societies of the Pacific Northwest, dance is a central part of Kwakwaka'wakw life, and is found at many rites and ceremonies. The dance is so important that each variety has to be carefully staged and prepared for. Special members of the tribe are designated to survey particular dances to see if they've been performed to satisfaction. Mistakes and poorly conducted dances could mean a loss of social position, or the stiffness of penalties; such as having to host a potlatch to regain prestige. The German anthropologist Franz Boas found a total of fifty-three different characters in Kwakwaka'wakw dance, each of them with a different role.

Tsetseka

Tsetseka ("Supernatural season" or "Winter Ceremonial") is perhaps the most important dancing ritual amongst the Kwakwaka'wakw.[28] The word comes from the Heiltsuk word for "shaman", and is used to refer to winter. The entire season is considered supernatural, and this is to be reflected in every ritual done during this time. The tsetseka dance was elaborately staged and planned by officials with specialized duties.[29] Novices who were to be initiated into the dance were carefully prepared for the ceremony, with instructions on dramatic acting, dancing and proper cries. Intricate props and stage illusions were made ready, from hidden strings and underground tunnels for magic tricks to pounding noise on the roof in a simulation of mythical birds.[29] The entire operation extended beyond the dancing house, as acts were deliberately planned for novices to be initiated into the ceremony. In one instance, a novice appeared to arrive on a canoe, but was drowned in an accident. Later he would be "revived" amidst much celebration. The figure that drowned was actually a wooden carving used to represent the novice.[29] During tsetseka, the entire Kwakwaka'wakw living space became a sort of live theater, in which terror, drama, illusion and comedy were fully exploited to create the atmosphere of the special season.

The hamatsa ritual was the most important dance in the tsetseka season. The purpose of the performance was to initiate a novice into a hamatsa dancer, the highest rank of dancer.[30] Only individuals who have danced for twelve years through the previous three grades can attempt this accomplishment.[30] The dance requires a large cast of characters, takes a total of four days to finish, and is steeped in ritual and drama. It is based around the legend of the hamatsa, terrible bird-like monsters that fed on human flesh.[30] In the ceremony, the novice is possessed by a hamatsa spirit, and disappears into the woods for four days. While possessed, the novice must dance and cry as if in a frenzy, and interact with the audience in a wild and violent way. After four days, the subject has been ritually tamed until he is "human" again. Achieving this state signifies the novice's acceptance into the dancing society as a full member.[30]

Conceptual art

David Neel (b. 1960), grandson of carver Ellen Neel, is a contemporary Kwakwaka'wakw painter, photographer, printmaker, and multimedia artist. His work demonstrates that Northwest Coastal art can meet the challenge of addressing current sociopolitical issues, for example his prints and masks that deal with land conflicts, radiation, oil spills, clear cutting, and overpopulation.[31]

Notable Kwakwaka'wakw artists

- Calvin Hunt, woodcarver

- Henry Hunt, woodcarver

- Richard Hunt, woodcarver

- Mungo Martin, woodcarver

- Beau Dick, artist, woodcarver

- David Neel, multimedia artist

- Ellen Neel, woodcarver

- Willie Seaweed, woodcarver

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 5

- ↑ Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 33

- ↑ Penney, p. 158

- ↑ Penney, p. 157

- ↑ Jonaitis, p. 243; Penney, p. 159

- 1 2 Jonaitis, p. 242

- ↑ Stewart, p. 133

- ↑ Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 20

- 1 2 Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 9

- ↑ Shearer, p. 54

- ↑ Shearer, pp. 40-43

- ↑ Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 185

- ↑ Shearer, pp. 17-81

- ↑ Shearer, p. 77

- 1 2 3 Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 27

- 1 2 Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 238

- ↑ Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 173

- ↑ Shearer, pp. 30-31

- ↑ Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 87

- ↑ Jonaitis, p. 30

- 1 2 3 4 Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 159

- ↑ Shearer, p. 24

- ↑ Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 70

- ↑ Shearer, pp. 105-6

- 1 2 Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 72

- 1 2 Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 56

- ↑ Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 250

- ↑ Penney, p. 159

- 1 2 3 Hawthorn, A. (1988) p. 39

- 1 2 3 4 Hawthorn, A. (1988) pp. 45-46

- ↑ Ryan, p. 233

References

- Falossi,F. and Mastropasqua,F. "L'Incanto Della Maschera." Vol. 1 Prinp Editore, Torino:2014 www.prinp.com ISBN 978-88-97677-50-5

- Hawthorn, Audrey. (1988). Kwakiutl Art. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-88894-612-0.

- Jonaitis, Aldona. (1988). From the Land of the Totem Poles: The Northwest Coast Indian Art Collection at the American Museum of Natural History. New York: American Museum of Natural History. ISBN 0-295-97022-7.

- Penney, David W. (2004). North American Indian Art. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20377-6

- Ryan, Allan J. (1999). The Trickster Shift: Humor and Irony in Contemporary Native Art. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0-7748-0704-0.

- Shearer, Cheryl. (2000). Understanding Northwest Coast Art. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 1-55054-782-8.

- Stewart, Hillary. (1993). Looking at Totem Poles. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978-1-55054-074-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kwakwaka'wakw art. |