Kurgan hypothesis

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe Caucasus East-Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South-Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East-Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

|

The Kurgan hypothesis (also known as the Kurgan theory or Kurgan model) or steppe theory is the most widely accepted proposal to identify the Proto-Indo-European homeland from which the Indo-European languages spread out throughout Europe and parts of Asia.[note 1] It postulates that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). The term is derived from the Russian kurgan (курган), meaning tumulus or burial mound.

The Kurgan hypothesis was first formulated in the 1950s by Marija Gimbutas, who used the term to group various cultures, including the Yamna, or Pit Grave, culture and its predecessors. David Anthony instead uses the core Yamna culture and its relationship with other cultures as a point of reference.

Marija Gimbutas defined the Kurgan culture as composed of four successive periods, with the earliest (Kurgan I) including the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures of the Dnieper-Volga region in the Copper Age (early 4th millennium BC). The people of these cultures were nomadic pastoralists, who, according to the model, by the early 3rd millennium BC had expanded throughout the Pontic-Caspian steppe and into Eastern Europe.[3]

Three genetic studies in 2015 gave support to the Kurgan theory of Gimbutas regarding the Indo-European Urheimat. According to those studies, haplogroups R1b and R1a, now the most common in Europe (R1a is also common in South Asia) would have expanded from the Russian steppes, along with the Indo European languages; they also detected an autosomal component present in modern Europeans which was not present in Neolithic Europeans, which would have been introduced with paternal lineages R1b and R1a, as well as Indo European Languages.[4][5][6]

History

Predecessors

Arguments for the identification of the Proto-Indo-Europeans as steppe nomads from the Pontic-Caspian region had already been made in the 19th century by German philologists Theodor Benfey[7] and especially Otto Schrader.[8][9] In his standard work[10] about PIE and to a greater extent in a later abbreviated version,[11] Karl Brugmann took the view that the urheimat could not be identified exactly at that time, but he tended toward Schrader’s view. However, after Karl Penka's 1883[12] rejection of non-European origins, most scholars favoured a Northern European origin. The view of a Pontic origin was still strongly favoured, e.g., by the archaeologists V. Gordon Childe[13] and Ernst Wahle.[14] One of Wahle's students was Jonas Puzinas, who in turn was one of Gimbutas’ teachers. Gimbutas, who acknowledges Schrader as a precursor,[15] was able to marshal a wealth of archaeological evidence from the territory of the Soviet Union (and other countries then belonging to the eastern bloc) not readily available to scholars from western countries,[16] enabling her to achieve a fuller picture of prehistoric Europe.

Overview

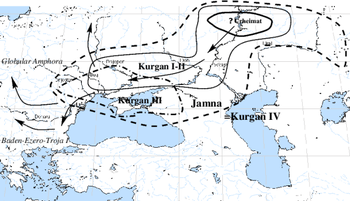

When it was first proposed in 1956, in The Prehistory of Eastern Europe, Part 1, Marija Gimbutas's contribution to the search for Indo-European origins was an interdisciplinary synthesis of archaeology and linguistics. The Kurgan model of Indo-European origins identifies the Pontic-Caspian steppe as the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) urheimat, and a variety of late PIE dialects are assumed to have been spoken across the region. According to this model, the Kurgan culture gradually expanded until it encompassed the entire Pontic-Caspian steppe, Kurgan IV being identified with the Yamna culture of around 3000 BC.

The mobility of the Kurgan culture facilitated its expansion over the entire region, and is attributed to the domestication of the horse and later the use of early chariots.[note 2] The first strong archaeological evidence for the domestication of the horse comes from the Sredny Stog culture north of the Azov Sea in Ukraine, and would correspond to an early PIE or pre-PIE nucleus of the 5th millennium BC.[note 2]

Subsequent expansion beyond the steppes led to hybrid, or in Gimbutas's terms "kurganized" cultures, such as the Globular Amphora culture to the west. From these kurganized cultures came the immigration of Proto-Greeks to the Balkans and the nomadic Indo-Iranian cultures to the east around 2500 BC.

Kurgan culture

Cultural horizon

Gimbutas defined and introduced the term "Kurgan culture" in 1956 with the intention of introducing a "broader term" that would combine Sredny Stog II, Pit-Grave and Corded ware horizons (spanning the 4th to 3rd millennia in much of Eastern and Northern Europe).[note 3] The model of a "Kurgan culture" brings together the various cultures of the Copper Age to Early Bronze Age (5th to 3rd millennia BC) Pontic-Caspian steppe to justify their identification as a single archaeological culture or cultural horizon, based on similarities among them. The eponymous construction of kurgans (mound graves) is only one among several factors. As always in the grouping of archaeological cultures, the dividing line between one culture and the next cannot be drawn with hard precision and will be open to debate.

Cultures that Gimbutas considered as part of the "Kurgan culture":

- Bug-Dniester (6th millennium)

- Samara (5th millennium)

- Khvalynsk (5th millennium)

- Dnieper-Donets (5th to 4th millennia)

- Sredny Stog (mid-5th to mid-4th millennia)

- Maikop-Dereivka (mid-4th to mid-3rd millennia)

- Yamna (Pit Grave): This is itself a varied cultural horizon, spanning the entire Pontic-Caspian steppe from the mid-4th to the 3rd millennium.

- Usatovo culture (late 4th millennium)

Stages of culture and expansion

Gimbutas' original suggestion identifies four successive stages of the Kurgan culture:

- Kurgan I, Dnieper/Volga region, earlier half of the 4th millennium BC. Apparently evolving from cultures of the Volga basin, subgroups include the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures.

- Kurgan II–III, latter half of the 4th millennium BC. Includes the Sredny Stog culture and the Maykop culture of the northern Caucasus. Stone circles, anthropomorphic stone stelae of deities.

- Kurgan IV or Pit Grave culture, first half of the 3rd millennium BC, encompassing the entire steppe region from the Ural to Romania.

In other publications[17] she proposes three successive "waves" of expansion:

- Wave 1, predating Kurgan I, expansion from the lower Volga to the Dnieper, leading to coexistence of Kurgan I and the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture. Repercussions of the migrations extend as far as the Balkans and along the Danube to the Vinča culture in Serbia and Lengyel culture in Hungary.

- Wave 2, mid 4th millennium BC, originating in the Maykop culture and resulting in advances of "kurganized" hybrid cultures into northern Europe around 3000 BC (Globular Amphora culture, Baden culture, and ultimately Corded Ware culture). According to Gimbutas this corresponds to the first intrusion of Indo-European languages into western and northern Europe.

- Wave 3, 3000–2800 BC, expansion of the Pit Grave culture beyond the steppes, with the appearance of the characteristic pit graves as far as the areas of modern Romania, Bulgaria, eastern Hungary and Georgia, coincident with the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture and Trialeti culture in Georgia (c.2750 BC).

Timeline

- 4500–4000: Early PIE. Sredny Stog, Dnieper-Donets and Samara cultures, domestication of the horse (Wave 1).

- 4000–3500: The Pit Grave culture (a.k.a. Yamna culture), the prototypical kurgan builders, emerges in the steppe, and the Maykop culture in the northern Caucasus. Indo-Hittite models postulate the separation of Proto-Anatolian before this time.

- 3500–3000: Middle PIE. The Pit Grave culture is at its peak, representing the classical reconstructed Proto-Indo-European society with stone idols, predominantly practicing animal husbandry in permanent settlements protected by hillforts, subsisting on agriculture, and fishing along rivers. Contact of the Pit Grave culture with late Neolithic Europe cultures results in the "kurganized" Globular Amphora and Baden cultures (Wave 2). The Maykop culture shows the earliest evidence of the beginning Bronze Age, and Bronze weapons and artifacts are introduced to Pit Grave territory. Probable early Satemization.

- 3000–2500: Late PIE. The Pit Grave culture extends over the entire Pontic steppe (Wave 3). The Corded Ware culture extends from the Rhine to the Volga, corresponding to the latest phase of Indo-European unity, the vast "kurganized" area disintegrating into various independent languages and cultures, still in loose contact enabling the spread of technology and early loans between the groups, except for the Anatolian and Tocharian branches, which are already isolated from these processes. The Centum-Satem break is probably complete, but the phonetic trends of Satemization remain active.

Further expansion during the Bronze Age

The Kurgan hypothesis describes the initial spread of Proto-Indo-European during the 5th and 4th millennia BC.[18] As used by Gimbutas, the term "kurganized" implied that the culture could have been spread by no more than small bands who imposed themselves on local people as an elite. This idea of the PIE language and its daughter-languages diffusing east and west without mass movement proved popular with archaeologists in the 1970s (the pots-not-people paradigm).[19] The question of further Indo-Europeanization of Central and Western Europe, Central Asia and Northern India during the Bronze Age is beyond its scope, far more uncertain than the events of the Copper Age, and subject to some controversy. The rapidly developing field of archaeogenetics and genetic genealogy since the late 1990s has not only confirmed a migratory pattern out of the Pontic Steppe at the relevant time,[20][21][22] it also suggests the possibility that the population movement involved was more substantial than anticipated.[23]

Revisions

Invasionist vs. diffusionist scenarios

Gimbutas believed that the expansions of the Kurgan culture were a series of essentially hostile, military incursions where a new warrior culture imposed itself on the peaceful, matriarchal cultures of "Old Europe", replacing it with a patriarchal warrior society,[24] a process visible in the appearance of fortified settlements and hillforts and the graves of warrior-chieftains:

The process of Indo-Europeanization was a cultural, not a physical, transformation. It must be understood as a military victory in terms of successfully imposing a new administrative system, language, and religion upon the indigenous groups.[25]

In her later life, Gimbutas increasingly emphasized the violent nature of this transition from the Mediterranean cult of the Mother Goddess to a patriarchal society and the worship of the warlike Thunderer (Zeus, Dyaus), to a point of essentially formulating a feminist archaeology.

Many scholars who accept the general scenario of Indo-European migrations maintain that the transition was probably much more gradual and peaceful than suggested by Gimbutas. The migrations were certainly not a sudden, concerted military operation, but the expansion of disconnected tribes and cultures, spanning many generations. To what degree the indigenous cultures were peacefully amalgamated or violently displaced remains a matter of controversy among supporters of the Kurgan hypothesis. J. P. Mallory (in 1989) accepted the Kurgan hypothesis as the de facto standard theory of Indo-European origins, but he recognized valid criticism of Gimbutas' radical scenario of military invasion:

One might at first imagine that the economy of argument involved with the Kurgan solution should oblige us to accept it outright. But critics do exist and their objections can be summarized quite simply – almost all of the arguments for invasion and cultural transformations are far better explained without reference to Kurgan expansions, and most of the evidence so far presented is either totally contradicted by other evidence or is the result of gross misinterpretation of the cultural history of Eastern, Central, and Northern Europe.[26]

Anthony's "Revised Steppe Theory"

David Anthony's The Horse, the Wheel and Language describes his "Revised Steppe Theory." David Anthony considers the term "Kurgan culture" so lacking in precision as to be useless, instead using the core Yamna culture and its relationship with other cultures as a point of reference.[27] He points out that

The Kurgan culture was so broadly defined that almost any culture with burial mounds, or even (like the Baden culture) without them could be included.[27]

He does not include the Maykop culture among those that he considers to be IE-speaking, presuming instead that they spoke a Caucasian language.[28]

See also

- Genetics

- Competing hypotheses

- Proto-Indo-European Urheimat hypotheses

- Armenian hypothesis

- Anatolian hypothesis

- Out of India theory

- Paleolithic Continuity Theory

Notes

- ↑ See:

- Mallory: "The Kurgan solution is attractive and has been accepted by many archaeologists and linguists, in part or total. It is the solution one encounters in the Encyclopædia Britannica and the Grand Dictionnaire Encyclopédique Larousse."[1]

- Strazny: "The single most popular proposal is the Pontic steppes (see the Kurgan hypothesis)..."[2]

- 1 2 Parpola in Blench & Spriggs (1999:181). "The history of the Indo-European words for 'horse' shows that the Proto-Indo-European speakers had long lived in an area where the horse was native and/or domesticated (Mallory 1989:161–63). The first strong archaeological evidence for the domestication of the horse comes from the Ukrainian Srednij Stog culture, which flourished c. 4200–3500 BC and is likely to represent an early phase of the Proto-Indo-European culture (Anthony 1986:295f.; Mallory 1989:162, 197–210). During the Pit Grave culture (c. 3500–2800 BC), which continued the cultures related to Srednij Stog and probably represents the late phase of the Proto-Indo-European culture – full-scale pastoral technology, including the domesticated horse, wheeled vehicles, stock breeding and limited horticulture, spread all over the Pontic steppes, and, c. 3000 BC, in practically every direction from this centre (Anthony 1986, 1991; Mallory 1989, vol. 1).

- ↑ >Gimbutas (1970) page 156: "The name Kurgan culture (the Barrow culture) was introduced by the author in 1956 as a broader term to replace and Pit-Grave (Russian Yamna), names used by Soviet scholars for the culture in the eastern Ukraine and south Russia, and Corded Ware, Battle-Axe, Ochre-Grave, Single-Grave and other names given to complexes characterized by elements of Kurgan appearance that formed in various parts of Europe"

References

- ↑ Mallory 1989, p. 185.

- ↑ Strazny 2000, p. 163.

- ↑ Gimbutas (1985) page 190.

- ↑ Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe, Haak et al, 2015

- ↑ Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia, Allentoft et al, 2015

- ↑ Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe, Mathieson et al, 2015

- ↑ Theodor Benfey, Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft und orientalischen Philologie in Deutschland seit dem Anfange des 19. Jahrhunderts, mit einem Rückblick auf die früheren Zeiten (Munich: J.G. Cotta, 1869), 597–600.

- ↑ Otto Schrader, Sprachvergleichung und Urgeschichte, vol. 2. Jena, Ger.: Hermann Costanoble, 1890.

- ↑ Rydberg, Viktor (1907). Teutonic Mythology. 1. London, UK: Norrœna. p. 19. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21.

- ↑ Karl Brugmann, Grundriss der vergleichenden Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen, vol. 1.1, Strassburg 1886, p. 2.

- ↑ Karl Brugmann, Kurze vergleichende Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen, vol. 1, Strassburg 1902, p. 22-23.

- ↑ Karl Penka, Origines Ariacae: Linguistisch-ethnologische Untersuchungen zur ältesten Geschichte der arischen Völker und Sprachen (Vienna: Taschen, 1883), 68.

- ↑ Vere Gordon Childe, The Aryans: A Study of Indo-European Origins (London: Kegan Paul, 1926).

- ↑ Ernst Wahle (1932). Deutsche Vorzeit, Leipzig 1932.

- ↑ Gimbutas, Marija (1963). The Balts. London, UK: Thames & Hudson. p. 38. Archived from the original on 2013-10-30.

- ↑ Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. pp. 18, 495. ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0.

- ↑ Bojtar 1999, p. 57.

- ↑ The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th edition, 22:587–588

- ↑ Razib Khan, Facing the ocean, Discover Magazine, 28 August 2012.

- ↑ Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe, Haak et al, 2015

- ↑ Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia, Allentoft et al, 2015

- ↑ Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe, Mathieson et al, 2015

- ↑ Haak 2015.

- ↑ Gimbutas (1982:1)

- ↑ Gimbutas, Dexter & Jones-Bley (1997:309)

- ↑ Mallory (1991:185)

- 1 2 David Anthony, The Horse, The Wheel and Language: How Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world (2007), pp. 306–7: "Why not a Kurgan Culture?"

- ↑ David Anthony, The Horse, The Wheel and Language: How Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world (2007), p. 297.

Sources

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-05887-3

- Anthony, David; Vinogradov, Nikolai (1995), "Birth of the Chariot", Archaeology, 48 (2), pp. 36–41

- Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew, eds. (1999), Archaeology and Language, III: Artefacts, languages and texts, London: Routledge

- Bojtar, Endre (1999), Foreword to the Past: A Cultural History of the Baltic People, Central European University Press

- Dexter, Miriam Robbins; Jones-Bley, Karlene, eds. (1997), The Kurgan Culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe: Selected Articles From 1952 to 1993, Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of Man, ISBN 0-941694-56-9.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1956), The Prehistory of Eastern Europe. Part I: Mesolithic, Neolithic and Copper Age Cultures in Russia and the Baltic Area, Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1970), "Proto-Indo-European Culture: The Kurgan Culture during the Fifth, Fourth, and Third Millennia B.C.", in Cardona, George; Hoenigswald, Henry M.; Senn, Alfred, Indo-European and Indo-Europeans: Papers Presented at the Third Indo-European Conference at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 155–197, ISBN 0-8122-7574-8.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1982), "Old Europe in the Fifth Millenium B.C.: The European Situation on the Arrival of Indo-Europeans", in Polomé, Edgar C., The Indo-Europeans in the Fourth and Third Millennia, Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers, ISBN 0-89720-041-1

- Gimbutas, Marija (Spring–Summer 1985), "Primary and Secondary Homeland of the Indo-Europeans: comments on Gamkrelidze-Ivanov articles", Journal of Indo-European Studies, 13 (1&2): 185–201

- Gimbutas, Marija; Dexter, Miriam Robbins; Jones-Bley, Karlene (1997), The Kurgan Culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe: Selected Articles from 1952 to 1993, Washington, D. C.: Institute for the Study of Man, ISBN 0-941694-56-9

- Gimbutas, Marija; Dexter, Miriam Robbins (1999), The Living Goddesses, Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-22915-0

- Haak, W.; Lazaridis, I.; Patterson, N.; Rohland, N.; Mallick, S.; Llamas, B.; Brandt, G.; Nordenfelt, S.; Harney, E.; Stewardson, K.; Fu, Q.; Mittnik, A.; Bánffy, E.; Economou, C.; Francken, M.; Friederich, S.; Pena, R. G.; Hallgren, F.; Khartanovich, V.; Khokhlov, A.; Kunst, M.; Kuznetsov, P.; Meller, H.; Mochalov, O.; Moiseyev, V.; Nicklisch, N.; Pichler, S. L.; Risch, R.; Rojo Guerra, M. A.; et al. (2015), "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe" (PDF), Nature, 522: 207–211, Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H, PMC 5048219

, PMID 25731166, doi:10.1038/nature14317

, PMID 25731166, doi:10.1038/nature14317 - Krell, Kathrin (1998). "Gimbutas' Kurgans-PIE homeland hypothesis: a linguistic critique". Chapter 11 in "Archaeology and Language, II", Blench and Spriggs.

- Mallory, J.P.; Adams, D.Q., eds. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, London: Fitzroy Dearborn, ISBN 1-884964-98-2.

- Mallory, J.P. (1989), In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-27616-1.

- Mallory, J.P. (1996), Fagan, Brian M., ed., The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-507618-4

- Renfrew, Colin. (1999). "Time depth, convergence theory, and innovation in Proto-Indo-European: 'Old Europe' as a PIE linguistic area." J INDO-EUR STUD, 27(3-4), 257-293.

- Schmoeckel, Reinhard (1999), Die Indoeuropäer. Aufbruch aus der Vorgeschichte ("The Indo-Europeans: Rising from pre-history"), Bergisch-Gladbach (Germany): Bastei Lübbe, ISBN 3-404-64162-0

- Strazny, Philipp (Ed). (2000), Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics (1 ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-1-57958-218-0

- Zanotti, D. G. (1982), "The Evidence for Kurgan Wave One As Reflected By the Distribution of 'Old Europe' Gold Pendants", Journal of Indo-European Studies, 10, pp. 223–234.

Further reading

- Gimbutas, Marija (1997). Dexter, Miriam Robbins; Jones-Bley, Karlene, eds. The Kurgan Culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe: Selected Articles From 1952 to 1993. Journal of Indo-European Studies Monograph Series No. 18. Institute for the Study of Man. ISBN 978-094169456-8.

- Mallory, J.P. (1999), In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth (reprint ed.), London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-27616-1

- Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse The Wheel And Language. How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped The Modern World. Princeton University Press.

External links

- humanjourney.us, The Indo-Europeans

- Charlene Spretnak (2011), Anatomy of a Backlash: Concerning the Work of Marija Gimbutas, Journal of Archaeomythology