Kundakunda

| Acharya Kundakunda | |

|---|---|

Idol of Acharya KundaKunda, Karnataka | |

| Religion | Jainism |

| Sect | Digambara |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1st century B.C.- 1st century C.E. |

| Disciple(s) | Umaswati |

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

Jain prayers |

|

Ethics |

|

Major sects |

|

Festivals |

|

|

Acharya Kundakunda is a revered Digambara Jain monk and philosopher. He authored many Jain texts such as: Samayasara, Niyamasara, Pancastikayasara, Pravachanasara, Atthapahuda and Barasanuvekkha. He occupies the highest place in the tradition of the Jain acharyas. Modern scholarship has found it difficult to locate him chronologically, with a possible low date in the 2nd-3rd centuries CE and a late date in 8th century.[1][2]

Names

His proper name was Padmanandin,[3] he is popularly referred to as Kundakunda possibly because the modern village of Kondakunde in Anantapur district of Andhra Pradesh might represent his native home.[4][5] A.N. Upadhye has shown that possibly apart from the name Elacarya, all the other names ascribed to Kundakunda (Vakragriva, Grdhrapiccha or Mahamati) go against the tradition of the early epigraphic records.[3]

Biography

Acharya Kundakunda belonged to the Mula Sangh order. He is closely associated with the Digambara sect, also in recent decades, his books have become popular among Śvētāmbaras also. He is dated to have flourished around second century CE by Natubhai Shah.[4]

For Digambaras, his name has auspicious significance and occupies third place after Lord Mahavira and Gautama Ganadhara in the sacred litany. Kundakunda's singular contribution consists in his compiling a number of liturgical tracts and creating several masterly doctrinal works of his own, which provided a parallel canon for the Digambara tradition. This earned him the everlasting gratitude of the Digambaras, who have for centuries invoked his name together with that of Mahavira and his Ganadhara, Gautama, placing him ahead even of Bhadrabahu, Visakha, and some forty other elders (sthaviras) in the lineage, thus making him virtually the founder of the Digambara sect.[6]

Dr. A.N. Upadhye in his critical edition of the Pravachansara has examined at great length the problems concerning the date and author-ship of these and other works attributed to Kundakunda and has placed him in the middle of the 2nd century AD.[7] This would make him the first significant and independent thinker of the post-canonical period whose views are accepted as representing the Jain thought.[8]

Thought

In texts such as Pravacanasāra (‘The Essence of the Doctrine’) and Samayasāra (‘The Essence of the Soul’), Kundakunda distinguishes between two perspectives of truth:

- vyavahāranaya or ‘mundane perspective’, also delusion (moha)

- niścayanaya or ‘ultimate perspective’, also called “supreme” (paramārtha) and “pure” (śuddha)[9]

For Kundakunda, the mundane realm of truth is also the relative perspective of normal folk, where the workings of karma operate and where things emerge, last for a certain duration and perish. The mundane aspect is associated with the changing qualities of the soul mainly the influx of karmic particles. The ultimate perspective meanwhile, is that of the pure soul or atman, the jiva, which is "blissful, energetic, perceptive, and omniscient".[10] Delusion and bondage is caused by the confusion of the workings of karma with the true nature of the soul, which is always pure, in other words, it is caused by taking the view of vyavahāranaya, not the higher niścayanaya which is the absolute perspective of a Jina - Kevala Jnana. According to Long, this view shows influence from Buddhism and Vedanta, which see bondage are arising from avidya, ignorance and see the ultimate solution to this in a form of spiritual gnosis.[11] While this is a somewhat heterodox view in light of Jainism's orthodox 'karmic realism' which sees karma as real physical particles which become attached to the soul, it has become a mainstream view in Digambara Jainism.[12]

Works

The works attributed to Kundakunda, all of them in Prakrit,[5] can be divided in three groups.

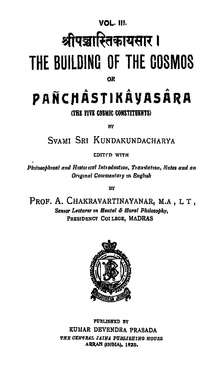

The first group comprises four original works described as "The Essence" (sara)— namely, the Niyamasara (The Essence of the Restraint, in 187 verses), the Pancastikayasara (The Essence of the Five Existents, in 153 verses), the Samayasara (The Essence of the Self, in 439 verses), and the Pravachanasara (The Essence of the Teaching, in 275 verses).[4]

The second group is a collection of ten bhaktis (devotional prayers), short compositions in praise of the acharya (Acharyabhakti), the scriptures (Srutabhakti), the mendicant conduct (Charitrabhakti), and so forth. They form the standard liturgical texts used by the Digambara in their daily rituals and bear close resemblance to similar texts employed by the Śvētāmbara, suggesting the possibility of their origin in the canonical period prior to the division of the community.

The last group consists of eight short texts called Prabhrta (Pkt. pahuda, i.e., a gift or a treatise), probably compilations from some older sources, on such topics as the right view (Darsanaprabhrta, in 36 verses), right conduct (Charitraprabhrta, in 44 verses), the scripture (Sutraprabhrta, in 27 verses), and so forth.

Various Jain texts mention that Acharya Kundkunda wrote '84 Pahurs', and only some of them are available at present.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Dundas, Paul; The Jains, page 107.

- ↑ Long, Jeffery; Jainism: An Introduction, page 66.

- 1 2 Balcerowicz 2003, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 48.

- 1 2 Upinder Singh 2008, p. 524.

- ↑ Jaini 1991, p. 32.

- ↑ Jaini 1991, p. 32–33.

- ↑ Balcerowicz 2003, p. 25.

- ↑ Long, Jeffery; Jainism: An Introduction, page 126.

- ↑ Long, Jeffery; Jainism: An Introduction, page 126.

- ↑ Long, Jeffery; Jainism: An Introduction, page 127.

- ↑ Long, Jeffery; Jainism: An Introduction, page 128.

References

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Kundkund's Samayasara, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-3-8

- Singh, Upinder (2008), A history of ancient and early medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century, New Delhi: Pearson Education, ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0

- Balcerowicz, Piotr, ed. (2003) [2002], Essays in Jaina Philosophy and Religion, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1977-2

- Cort, John E. (10 July 1998), Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-3785-X

- Jaini, Padmanabh (1991), Gender and Salvation: Jaina Debates on the Spiritual Liberation of Women, Berkeley: University of California Press

- Shah, Natubhai (2004) [First published in 1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, I, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1938-1