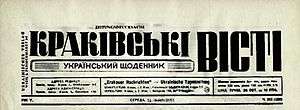

Krakivs'ki Visti

|

Krakivs'ki Visti frontispiece | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Tabloid |

| Editor-in-chief | Michael Chomiak (a.k.a. Mykhailo Khomiak) |

| Founded | 1940 |

| Political alignment | Nazi Party |

| Language | Ukrainian |

| Ceased publication | 1945 |

| Headquarters | Kraków, General Government (later in Vienna) |

| Circulation | 16,808 (1944) [1] |

The Krakivs'ki Visti (Ukrainian: Краківські вісті: народний часопис для Генерал-Губернаторства, German: Krakauer Nachrichten – Ukrainische Tageszeitung),[2] was a vehemently antisemitic,[3] Nazi propaganda daily, published during World War II in the Ukrainian language with the German financial aid, and with exposure orchestrated by Joseph Goebbels himself.[4]

Content

Krakivs'ki visti, with headquarters in Kraków since 1940, republished materials from the German papers for distribution in the General Government territory of occupied Poland, especially the Nazi party organ Völkischer Beobachter, which appeared frequently. The articles were also translated from Berliner Illustrierte Nachtausgabe and all most important German papers.[4][5] The Krakivs'ki Visti was distributed in Nazi Germany among the Ukrainian Ostarbeiter workers for the purpose of indoctrination especially after the anti-Soviet Operation Barbarossa of 1941, but also throughout other German-occupied countries. The company was moved to Vienna in 1944 ahead of the Soviet counteroffensive. The last issue was published on March 29, 1945.[1]

The editor-in-chief was Mykhailo Khomiak, a Nazi collaborator, who emigrated to Canada after World War II as Michael Chomiak.[6][7][8][9] Khomiak's granddaughter, Chrystia Freeland, is Canada's Minister of Foreign Affairs. Some Canadian officials have claimed in 2017 that the circulation of news regarding Chomiak's connection to Nazism was the result of a Russian disinformation campaign.[8][9][10] Nevertheless these facts have been confirmed by the University of Alberta historian, Professor John-Paul Himka,[8] among others.[11] The anti-Jewish materials published in Krakiws'ki Visti contributed in no small way to atmosphere conductive to the mass murder of Jews, wrote Himka.[12]

Circulation

The daily was closely associated with the Ukrainian Central Committee headed by Volodymyr Kubiyovych. It was more autonomous than other Ukrainian-language publication under the German rule. The press run was just over 10,000 in 1941 and just over 15,000 in 1943. Krakivs'ki visti was not distributed in the Reichskommissariat Ukraine. After the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939 in accordance with the Nazi-Soviet Pact, many Ukrainian nationalists left the Soviet-controlled Kresy for the German zone of occupation, and Kraków became the centre of their nationalist activity. Some of the most prominent Ukrainian writers contributed to Krakivs’ki visti. However, there were very few Ukrainians living in Kraków, therefore most copies were distributed elsewhere.[4]

Notes

- 1 2 Karl Waldmann Museum. "Page from an Ukrainian newspaper Krakivs'ki Visti, December 1944". Galerie Pascal Polar, Belgium.

- ↑ Digital collections (2017). "Krakivs'ki Visti : narodnij časopis dlja General-Gubernatorstva, 1940-1942". Biblioteka Jagiellońska. Uniwersytet Jagielloński. Katalog Druków XIX-XX w. ze zbiorów byłej Pruskiej Biblioteki Państwowej w Berlinie przechowywanych w Bibliotece Jagiellońskiej. Roczniki czasopisma: 3 wol,; sygnatury BPC 2483 IV LIND, Ztg 2475. Lista roczników: 001 r. 1940 (sičen-červen; lipen-veresen); 003 r. 1942 (lipen-gruden).

- ↑ John-Paul Himka. "First Escape: Dealing with the Totalitarian Legacy in the Early Postwar Emigration". Ukemonde.com. Ukrainian Community in Montreal.

The originals were vehemently antisemitic.

- 1 2 3 John-Paul Himka. "Ethnicity and the Reporting of Mass Murder: Krakivs'ki visti, the NKVD Murders of 1941, and the Vinnytsia Exhumation" (DOC). Time and Space. Lviv: University of Alberta.

- ↑ Rebecca Wetherbee (May 20, 2013). "Chrystia Freeland – U.S. Managing Editor, Financial Times". Little Pink Book.

- ↑ Robert Fife, Ottawa Bureau Chief (March 7, 2017). "Freeland knew her grandfather was editor of Nazi newspaper". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ David Pugliese (March 8, 2017). "Chrystia Freeland’s granddad was indeed a Nazi collaborator – so much for Russian disinformation". Ottawa Citizen.

Chomiak edited the paper first in Krakow (Cracow), Poland and then in Vienna. The reason he edited the paper in Vienna was because he had to flee with his Nazis colleagues as the Russians advanced into Poland.

- 1 2 3 Colby Cosh (March 8, 2017). "Of course it’s ‘news’ that Freeland’s grampa was a Nazi collaborator, even if the Russians are spreading it". National Post.

- 1 2 Paula Simons: 'School of hate': Was Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland's grandfather a Nazi collaborator?

- ↑ Terry Glavin: Enter the Freeland-Nazi conspiracy — and the amping-up of Russia’s mischief in Canada.

- ↑ Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe (Berlin). "Celebrating Fascism and War Criminality in Edmonton" (PDF). The Political Myth and Cult of Stepan Bandera in Multicultural Canada. Kakanien Revisited, No 12, 2010: 7–8.

The newspaper Krakivs’ki visti not only reprinted German anti-Semitic propaganda but also featured articles written by Ukrainian intellectuals who responded to German requests to write nationalistic and anti-Semitic materials. Indeed, Volodymyr Kubiiovych (former director of the Ukrainian Central Committee – Ukraїns’kyi Tsentral’nyi Komitet, UTsK) in Berlin contributed to the newspaper.55 Furthermore, he asked the head of the General Government, Hans Frank, to see »a very significant part of confiscated Jewish wealth turned over to the Ukrainian people«.

- ↑ John-Paul Himka (2013). Omer Bartov, Eric D. Weitz, eds. Ethnicity and the Reporting of Mass Murder. Shatterzone of Empires: Coexistence and Violence in the German, Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman Borderlands. Indiana University Press. p. 619. ISBN 0253006392.