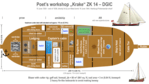

Krake ZK 14

Krake, 1934–1938 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Ebenhaëzer |

| Namesake: | Eben-Ezer |

| Owner: | Betto and Maarten Bolt |

| Operator: | do. |

| Port of registry: | Zoutkamp, Netherlands |

| Route: | North Sea, Wadden Sea, Lauwersmeer |

| Homeport: | Zoutkamp, Netherlands |

| Identification: | ZK 14 (ex ZK 74) |

| Fate: | sold to Germany, 25 Feb 1934 |

| Status: | commercial fishery vessel |

| Owner: | Martin Luserke |

| Operator: | do. |

| Acquired: | 25 Feb 1934 |

| Renamed: | Krake |

| Refit: | restoration, new superstructures (wheel house, elevated cabin roof on foredeck), new engine |

| Homeport: | Juist, Germany (until August 1934) |

| Identification: | ZK 14, call signal DGIC |

| Status: | swimming poet's workshop |

| Name: | Krake |

| Owner: | Martin Luserke |

| Operator: | do. |

| Homeport: | Emden, Germany |

| Identification: | ZK 14 |

| Fate: | destroyed by Allied bomb, 18 June 1944, Hamburg-Finkenwerder wharf |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Wadden sailer |

| Type: | Aak |

| Length: | 11 m (36 ft) |

| Beam: | 4 m (13 ft) |

| Height: | 13 m (43 ft) at main mast |

| Draught: | 0.5–0.8 m (1 ft 8 in–2 ft 7 in) |

| Installed power: | Deutz MDO engine |

| Propulsion: | 16–20 hp (12–15 kW) auxiliary engine |

| Sail plan: | 80 m2 (860 sq ft) sail area |

| Speed: | 6 kn = 11 km/h |

Krake was a Dutch sailing ship with the identifier ZK 14. It was bought by the German progressive pedagogue, bard and writer Martin Luserke. The former fishery vessel was deployed as his swimming poet's workshop. It cruised the shallow coastal regions of The Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, Southern Norway and Southern Sweden as well as channels and rivers between North Sea and Baltic Sea. In harbours it was visited by a larger quantity of mostly younger people who attended readings and taletelling. Krake became very well-known during 1934 and 1938 and still is a topic in German literature, scientific literature, local museums, libraries[1], archives[2], encyclopaedia[3] and lectures[4]. One of its later well-known visitors was Beate Uhse.

Name

Luserke named the ship Krake (= octopus) since he found a lot of stone jars (in old German language called Kruke) on it. Despite their completely different meaning both words sound similar which triggered the idea. Even his ship pet parakeet's name was created this way. It was named Kraki which is a belittlement of Krake, but was then modified to Karaki.[5]

History

Ebenhaëzer ZK 14 (ex ZK 74)

The Dutch fishery vessel Ebenhaëzer with the identifier ZK 14 (ex ZK 74) was formerly owned by Betto and Maarten Bolt of Zoutkamp, The Netherlands. Between 1911 and 1934 the open Aak was deployed to trawl fish, especially mussels, plaice, prawn and some herring. The ship probably originates from 19th century but its early history is not documented.[6] When Luserke bought the ship on 25 February 1934 it was reportedly overlain for a longer time.[7] So despite its construction of solid oak the ship was unkempt and already in a rather shabby condition. On its four-day-conversion tour to East Frisia in Northern Germany the cabin under deck broke down.

Krake ZK 14

On wharf in Oldersum, East Frisia, the ship was completely restored, renovated and newly developed with superstructures like a wheel house and an elevated under deck roof on its foredeck to gain a bit more headroom for its crew and guests. The vessel also got a new Deutz engine. The ship's identifier ZK 14 was inherited on its gaff sail whereas the identification on both sides of its bow was overwritten by its new name Krake. The vessel became a white paint coating but its flat floor plate was painted in black. Any metal panelling was silvery.

On Sunday, 15 June 1934, the ship was ready for the maiden voyage with its all-new engine. Martin Luserke and his fifteen-year-old son Dieter (1918–2005) boarded in Oldersum and went back to their home on the island Juist, which is one of the sandbanks which delimit the Wadden Sea. His son was already sailing since his 6th birthday so he owned some basic skills.

Martin Luserke was dedicated to the fine arts but also possessed a hands-on mentality. In 1906 he was co-founder of Freie Schulgemeinde Wickersdorf (= Free School Community of Wickersdorf) in Thuringia and in 1925 had founded Schule am Meer (= School by the Sea) on Juist Island. In the latter, where he built up a botanical garden in the dunes, eleven vegetable gardens for the school's self-supply, and a nationwide unique school theatre building, his motto was education by sea. He enabled his pupils to learn about sailing with the school's own sail boats (dinghy cruisers) or to signalise. One of his educational goals was to form his pupils' attitude, an earthiness, comradeship and their sense of team responsibility, leading to an autonomous personality. The latter turned out to be incompatible with Nazism.

When Luserke's school had to close in spring 1934 against the background of Gleichschaltung (= Nazification) and Antisemitism he asked his son if he wanted to follow him at sea. His wife Annemarie (1878–1926) had died early. As an answer he got an immediate yes from the sail enthusiast. With a talented teacher as father his son Dieter felt he could easily quit school.

As a professional preparation his son went aboard the 100-ton-sailship "Ostfriesland" (= East Frisia) which anchored near Juist at that time. There he hoped to learn the necessary until midth of June 1934. In 1931 his father had already completed a mate's certificate in Leer, East Frisia. Until August 1934 father and son both used Juist as their home port whilst school matters had to be cleared. Later their trips with Krake went from the Dutch West Frisian Islands along the German East Frisian Islands, to Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the German islands in the Baltic Sea like Fehmarn, Hiddensee, Rügen and Usedom, through Dutch, German and Danish channels, rivers and lakes like Schweriner See which they also used to hibernate.

Krake became well-known in the harbours since the ship was neither used for commercial fishery nor for cargo which was rather uncommon at that time of economic uncertainty. Especially younger people felt attracted to the readings and taletelling aboard Krake. Luserke's stories got formed with each taletelling and were finally written down. Prior he always checked out his listener's reactions. He had a typewriter and a small book inventory aboard. Even the press got interested when in 1935 an Austrian press photographer came aboard for a home story.[8]

Another reason for the ship's reputation depicted an unusual decoration of its inner cabin walls. Harbourmasters and Customs officers who had to inspect the ship worked up curiosity for those strange figurative to symbolical carvings. Luserke created them during his time as POW in France between 1917 and 1918. They added to the theatrical effects of Luserke's taletelling and readings in a similar way than harsh weather conditions or the pounding of the waves against the ship's body. Luserke's use of ancient Norse and Breton myths and legends as well as dramatic ghost stories from the coast provoked a certain thrill. The prestigious writer Carl Zuckmayer who felt an antipathy for him, regarded Luserke as "of extensive phantasy, originality, capability at the highest stage" with a tremendous talent "of artistics, especially theatric".[9][10]

His former pupils from Thuringia and Juist Island as well as teacher colleagues came aboard but also unknown guests like hitchhikers who attended the ship for free trips. Luserke integrated them in the daily work aboard. It revealed his pedagogic background. One of his guests who later became well-known was Beate Uhse.[11] In her memoirs she wrote about Luserke as her most favourite teacher characterizing him as "appreciative", "generous" and "full of wit".[12] She became one of the first lady-pilots to test new planes.

The city of Emden fascinated Luserke, so there he rented a flat for himself and his son to hibernate.[13] He explored the city's library and archive for his historical research. In its Falderndelft harbour several of Luserkes books were created which became bestsellers during the 1930s and 1940s. In 1935 Luserke was awarded with Literaturpreis der Reichshauptstadt Berlin for his novel Hasko which reflects two historic sea battles of the Dutch Watergeuzen near Ameland and Emden.[14]

Luserke developed a very special relation to his fictional book Obadjah and the ZK 14 which incorporates his ship and those many empty stone jars originally meant for hard liquor which he had found aboard.[15] Some of his other books also include the ship and his own impressions.[16][17][18]

At the end of 1938 Luserke went off board and settled in Meldorf, Holstein, where he continued to write successfully.

On 18 June 1944 Krake was completely destroyed on wharf in Hamburg-Finkenwerder, where an Allied bomb directly hit.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Krake ZK 14. |

- Dieter Luserke: Mit meinem Vater Martin Luserke an Bord des guten Schiffes KRAKE-ZK 14 (1988) (in German)

- Martin Kiessig: Die alte ZK 14. Zu Besuch auf einer schwimmenden Dichterwerkstatt. Citation from: Martin Luserke. Gestalt und Werk. Versuch einer Wesensdeutung. Phil. Dissertation, University of Leipzig, Germany, J. Särchen Verlag, Berlin 1936. (in German)

- Press picture (Ullstein Verlag, Berlin): Dieter Luserke (1918–2005) aboard Krake in 1935, published by German periodical Die Dame, Vol. 24 (1935), Photographer: Lothar Rübelt.

References

- ↑ Krake. Johannes A. Lasco Bibliothek (library) in Emden, East Frisia, Germany.

- ↑ Krake. Schiffshistorisches Archiv (historic ship's archive), Flensburg, Germany

- ↑ Albrecht Sauer: Martin Luserke. Series: The Oxford Encyclopedia of Maritime History. Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0195130751.

- ↑ Die Lebensfahrt des Martin Luserke, lecture by Professor Kurt Sydow on the occasion of the 100st birthday of Martin Luserke, 3 May 1980, published as Die Lebensfahrt eines großen Erzählers – Martin Luserke (1880–1968), in: Jahrbuch des Archivs der deutschen Jugendbewegung Vol. 12, 1980.

- ↑ Dieter Luserke: Mit meinem Vater Martin Luserke an Bord des guten Schiffes KRAKE-ZK 14 , 1988 (in German)

- ↑ Archive of Visserijmuseum Zoutkamp, Noord-Nederland: Registration Card of Z.K. 14 Ebenhaëzer (ex Z.K. 74). Personal inquiry and photo by Daan Oostindiën of Zoutkamp, 9 Aug 2017.

- ↑ Iris Hellmich: Auf den Spuren des Schriftstellers Martin Luserke, published by: Emder Zeitung, weekly magazine, Series: Emder erzählen (sequence 127), 5 July 1997.

- ↑ Press picture: Dieter Luserke (1918–2005) aboard Krake in 1935, published by: periodical Die Dame, Vol. 24 (1935), photographer: Lothar Rübelt.

- ↑ Geheimreport (advance publication), in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 14 February 2002

- ↑ Gunther Nickel, Johanna Schrön (Ed.): Geheimreport. Wallstein, Göttingen 2002, ISBN 978-3-89244-599-9, p. 160.

- ↑ Picture (undated): Martin Luserke (left), his former pupil Beate Köstlin (later: Uhse) and teacher Erne Wehnert (right) from Schule am Meer on Juist Island (later teaching in Ahrenshoop) aboard Krake.

- ↑ Beate Uhse: Mit Lust und Liebe – Mein Leben. Ullstein, Frankfurt and Berlin 1989. ISBN 3-550-06429-2, pp. 53–55.

- ↑ Acc. to his son Dieter Luserke he rented a flat near Falderndelft harbour in Emden at Beuljenstrasse 4.

- ↑ Martin Luserke: Hasko – Ein Wassergeusen-Roman. Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1936. (new edition: ISBN 978-3-922117-99-5)

- ↑ Martin Luserke: Obadjah und die ZK 14 oder Die fröhlichen Abenteuer eines Hexenmeisters. Ludwig Voggenreiter Verlag, Potsdam 1936.

- ↑ Martin Luserke: Krake kreuzt im Nordmeer – Logbuch 1937, incl. drawings by Willy Thomsen (1898–1969). Verlag Philipp Reclam jun., Leipzig 1937.

- ↑ Martin Luserke: Das Logbuch des guten Schiffs Krake DGIC von seiner vierten Dänemark-Fahrt 1936 nach Holtenau, rund um Seeland über Stralsund nach Kappeln (Schleswig) zurück, incl. drawings by Dieter Evers. Ludwig Voggenreiter Verlag, Potsdam 1937. (new edition: ISBN 978-7-00-005031-0)

- ↑ Martin Luserke: Der Teufel unter der ZK 14 as part of the anthology Der kleine Schühss – Ein Buch von der Wattenküste, incl. drawings by Karl Stratil (1894-1963). Rolf Italiaander (1913–1991) (Ed.), epilogue by Martin Kiessig (1907–1994). Verlag Gustav Weise, Leipzig 1935.