Loulan Kingdom

| Krorän | |

|

A carved wooden beam from Loulan, 3rd-4th century. The patterns show influences from ancient western civilizations. | |

Shown within Xinjiang | |

| Location | Xinjiang, China |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°31′39.48″N 89°50′26.32″E / 40.5276333°N 89.8406444°ECoordinates: 40°31′39.48″N 89°50′26.32″E / 40.5276333°N 89.8406444°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

Loulan, also called Krorän or Kroraina (simplified Chinese: 楼兰; traditional Chinese: 樓蘭; pinyin: Lóulán; Uyghur: كروران, Кроран, ULY: Kroran) and known to Russian archaeologists as Krorayina, was an ancient kingdom based around an important oasis city along the Silk Road already known in the 2nd century BCE on the northeastern edge of the Lop Desert.[1] The term Loulan is the Chinese transcription of the native name Krorän and is used to refer to the city near Lop Nur as well as the kingdom.

The kingdom was renamed Shanshan (鄯善) after its king was assassinated by an envoy of the Han dynasty in 77 BCE;[2] however, the town at the northwestern corner of the brackish desert lake Lop Nur retained the name of Loulan. The kingdom included at various times settlements such as Niya, Charklik, Miran, and Qiemo. It was intermittently under Chinese control from the early Han dynasty onward until its abandonment centuries later. The ruins of Loulan are near the now-desiccated Lop Nur in the Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang, and they are now completely surrounded by desert.[3]

History

A number of mummies, now known as the Tarim mummies, have been found in Loulan and in its surrounding areas. One female mummy has been dated to c. 1800 BCE (3,800-year-old), indicating very early settlement of the region.[4]

Loulan was on the main route from Dunhuang to Korla, where it joined the so-called "northern route," and was also connected by a route southwest to the kingdom’s seat of government in the town of Wuni in the Charkhlik/Ruoqiang oasis, and from thence to Khotan and Yarkand.[5]

Early Han Dynasty

The first historical mention of Loulan was in a letter from the Chanyu of the Xiongnu to the Chinese Emperor in 126 BCE in which he boasted of conquering the Yuezhi, the Wusun, Loulan, and Hujie (呼揭), "as well as the twenty-six states nearby." In 126 BCE, the Chinese envoy Zhang Qian described Loulan as a fortified city near Lop Nur.[6]

Because of its strategic position on what became the main route from China to the West, during the Han dynasty, control of it was regularly contested between the Chinese and the Xiongnu until well into the 2nd century CE.[7] In the Book of Han, the early interactions of Loulan with the Han court were described in some detail.[8]

In the 2nd century BCE, Emperor Wu of Han was interested in extending contact with Dayuan (Fergana) after receiving reports of the country from Zhang Qian. However, according to Chinese sources, Han envoys to Fergana were harassed by Loulan and Gushi. In 108 BCE,[9] Loulan was attacked by a Han force led by Zhao Ponu (趙破奴) and its king captured, after which Loulan agreed to pay a tribute to Han China.[10] The Xiongnu, on hearing of these events, also attacked Loulan. The king of Loulan therefore elected to send one of his sons as a hostage to the Xiongnu, and another to the Han court.

The king of Loulan was then taken to the Han court and interrogated about his association with the Xiongnu. The Book of Han records:

The Emperor commanded [Jen] Wen to lead the troops by a suitable route, to arrest the king of Lou-lan and to bring him to the palace at the capital city. [Jen Wen] interrogated by presenting him with a bill of indictment, which he answered by claiming that [Lou-lan] was a small state lying between large states, and that unless it subjected itself to both parties, there would be no means of keeping itself in safety; he therefore wished to remove his kingdom and take up residence within the Han territory.— Hanshu, chapter 96a, translation from Hulsewé 1979.[11]

The Han emperor was satisfied with the statement and released the king.

In 92 BCE, the king of Loulan died, and his countrymen requested that the king's son be returned to Loulan. However, the Han court had castrated his son for infringement of Han laws and so it refused the request, claiming that the Han Emperor had grown too fond of him to let him go. Another king was installed in Loulan, and again a son was sent as hostage when demanded by the Han court. After the death of this king, the Xiongnu returned the hostage son sent to them, named Chang Gui or An Gui (嘗歸 or 安歸), to Loulan to rule as king. The Han, on hearing this, demanded that the new king present himself to the Han court. This, on his wife's advice, the king refused, on account of the fact that neither of the hostage sons sent to the Han court had been returned.

In 77 BCE, the Chinese envoy Fu Jiezi was sent to kill the Loulan king after several Han envoys were intercepted and killed. He arrived on the pretext of carrying gold and valuables to the outer states and intending to present the king with gifts, but stabbed the Loulan king to death while he was drunk, and had the severed head of the king hung from the northern gate tower.[12] The king's younger brother Weituqi (尉屠耆) was then installed as the king of Loulan by the Han court, and the kingdom was renamed Shanshan.[13]

Shanshan

After the Han dynasty had gained control of Loulan, the renamed kingdom of Shanshan became a Chinese puppet state.[14] The newly installed king, fearing retribution from the sons of the assassinated king, requested that a contingent of Han forces be established in Yixun (伊循, variously identified as Charklik or Miran). Chinese army officers were sent to colonise the area and an office of commandant was established at Yixun.[15] A number of settlements in the Tarim Basin such as Qiemo and Niya were described in the Book of Han as independent states, but these later became part of Shanshan. While the name of the kingdom was changed to Shanshan by the Chinese, the Loulan region continued to be known as Kroran by the locals.

The region remained under Chinese control intermittently, and when China was weak in the Western Regions, Loulan was essentially independent. In 25 CE it was recorded that Loulan was in league with the Xiongnu. In 73 CE, the Han army officer Ban Chao went with a small group of followers to Shanshan, which was also receiving a delegation from the Xiongnu at the same time. Ban Chao killed the Xiongnu envoys and presented their heads to the King, after which King Guang of Shanshan submitted to Han.[16] Around 119, Ban Yong recommended that a Chinese colony of 500 men be established in Loulan.[17] A later military colony was established at Loulan by General Suo Man. It was recorded that in 222 CE, Shanshan sent tribute to China, and that in 283, the son of the king was sent as a hostage to the Chinese court during the reign of Emperor Wu of Jin.[18] Loulan was also recorded as a dependent kingdom of Shanshan in the 3rd century Book of Wei.[19]

The town of Loulan was abandoned in 330 CE due to lack of water when the Tarim River, which supported the settlement, changed course; the military garrison was moved 50 kilometres (31 mi) south to Haitou (海頭). The fort of Yingpan to the northwest remained under Chinese control until the Tang dynasty.[20] According to the Book of Wei, King Bilong of Shanshan fled to Qiemo together with half of his countrymen after an attack by Juqu Anzhou in 442 CE so Shanshan came to be ruled by Qiemo.[21] In 445 Shanshan submitted to the Northern Wei. At the end of the 6th century, the Sui dynasty reestablished the city state of Shanshan.[14]

After the 5th century, however, the land was frequently invaded by nomadic states such as Tuyuhun, the Rouran Khaganate, and the Dingling and the area gradually was abandoned. Circa 630, at the beginning of the Tang period, Shanfutuo (鄯伏陁) led the remaining Shanshan people to Hami.[14]

The Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang passed through this region in 644 on his return from India to China, visited a town called Nafubo (納縛波, thought to be Charklik) of Loulan, and wrote of Qiemo, "A fortress exists, but not a trace of man".[22]

Descriptions in historical accounts

According to the Book of Han, Han envoys described the troops of Loulan as weak and easy to attack.[23] Shanshan was said to have 1570 households and 14,000 individuals, with 2912 persons able to bear arms.[24] It further described the region thus:

The land is sandy and salt, and there are few cultivated fields. The state hopes to obtain [the produce of] cultivated fields and look to neighbouring states for field-crops. It produces jade and there is an abundance of rushes, tamarisk, the balsam poplar, and white grass. In company with their flocks and herds the inhabitants go in search of water and pasture, and there are asses, horses and large number of camels. [The inhabitants] are capable of making military weapons in the same way as the Ch'o of the Ch'iang tribes.[25]

According to the Commentary on the Water Classic, General Suo Mai (索勱, also Suo Man) of Dunhuang introduced irrigation techniques to the region by damming the Zhubin (possibly the Kaidu River) to irrigate the fields and produced bumper harvests for the next three years.[26]

The Buddhist pilgrim Faxian who stayed in Shanshan in 399 on the way to India, described the country:

[A] country rugged and hilly, with a thin and barren soil. The clothes of the common people are coarse, and like those worn in our land of Han, some wearing felt and others coarse serge or cloth of hair; — this was the only difference seen among them. The king professed (our) Law, and there might be in the country more than four thousand monks who were all students of the hînayâna. The common people of this and other kingdoms (in that region), as well as the śramans, all practise the rules of India, only that the latter do so more exactly, and the former more loosely.— A Record of the Buddhist Countries, translation by James Legge[27]

Ethnolinguistic identity

The earliest known residents in Loulan are thought to be a subgroup of the Tocharians, an Indo-European people of the Tarim Basin. Excavations in Loulan and the surrounding areas have found mummies believed to be remains of these people, for example the so-called "Beauty of Loulan" which was found by Chinese archaeologists in 1979–1980 at Qäwrighul around 70 km west of Loulan. The mummies have been dated to as early as 1800 BCE.[4][28]

Loulan's first known language, the Krorainic, is usually called "Tocharian C".[29] However, the official language found in 3rd century CE documents in this region is Gandhari Prakrit written in Kharosthi script; their use in Loulan and elsewhere in the Tarim Basin was most likely due to the cultural legacy of the Kushan Empire,[30] and introduced by Gandharan migrants from the Kushan Empire.[31] These Gandharan migrants are also believed to have also introduced Buddhism to Loulan.[31] Although Gandhari was used as the administrative language, some words generally thought to be Tocharian are found in the documents, suggesting that the locals spoke a language that belongs to the Tocharian group of languages.[30][32] This putative Tocharian variant has been partially reconstructed from around 100 loanwords and over a thousand proper names used in these Prakrit documents that cannot be ascribed to Indic.[32]

The native name of Loulan was "Kroraina" or "Krorän",[33][30] written in Chinese as Loulan 樓蘭 (*glu-glân in reconstructed Han dynasty pronunciation, an approximation of Krorän).[34] Centuries later in 664 CE the Tang Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang mentioned a place in Loulan named "Nafupo" (納縛溥), which according to Dr. Hisao Matsuda is a transliteration of the Sogdian word Navapa meaning "new water."[35] Sogdians, an Eastern Iranian people, maintained minority communities in various places in China at the time,[36] especially Dunhuang in Gansu and Turfan in the Tarim Basin.[37][38] Documents found in Loulan showed that Sogdians were present in the area in 313 CE, as well as Han Chinese and Tibetan tribesmen, indicating an ethnically diverse population in Loulan.[30]

Archaeology

Sven Hedin

The ruined city of Loulan was discovered by Sven Hedin, who excavated some houses and found a wooden Kharosthi tablet and many Chinese manuscripts from the Western Jin Dynasty (265–420), which recorded that the area was called "Krorän" by the locals in Kharosthi but was rendered as "Lou-lan" in Chinese.[14][39] Hedin also proposed that a change in the course of the Tarim river resulted in Lop Nur drying up may be the reason why Loulan had perished.[14]

Aurel Stein

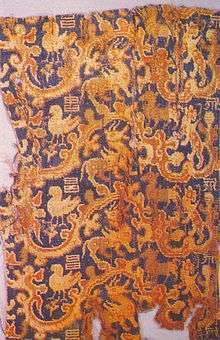

Aurel Stein made further excavations in 1906 and 1914 around the old lake of Lop Nur and identified many sites in the area. He designated these sites with the letter L (for Loulan), followed by a letter of the alphabet (A to T) allocated in the chronological order the sites were visited.[40] Stein recovered many artifacts, including various documents, a wool-pile carpet fragment, some yellow silk, and Gandharan architectural wood carvings.

L.A. - A walled settlement lying to the north of the lake. The thick wall is made of packed earth and straw and was over 1,000 feet (300 m) on each side and 20 feet (6.1 m) thick at the base. It contains a large stupa and some administrative buildings and was occupied for a long time. It is usually thought to be the city of Loulan.

L.B. - A site with stupas at 13 km to the northwest of the L.A.

L.E. - A fortified town lying 30 km to the northeast of L.A. It is the only known city in the region with a northern gate. Since a northern gate was mentioned in the Han Chinese text about the assassination of the king of Loulan, it has therefore been suggested to be the capital of Loulan in the 1st century BCE, before the Han Chinese gained control the region. Others, however, argue that the northern gate does not refer to Loulan but Chang'an. The site was occupied until the late 3rd century CE.

L.F. - 10 km to the northwest of L.A., containing building foundations and a cemetery. Archaeologists discovered the body of a young man in a wooden coffin, wearing a felt hat and leather boots and lying under a woolen blanket. A bunch of ephedra twigs was placed beside him in a similar fashion to many much older burials found in the region.

L.K. - A walled city to the west of the lake with only a gateway in the city wall. It has been identified as Haitou by some archaeologists.[41]

L.L. - A fortress lying 5 km northwest of L.K., similar in construction to but smaller.

Chinese archaeological expedition, 1979-1980

In 1979 and 1980, three archaeological expeditions sponsored by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Xinjiang Branch performed excavations in Loulan.[42] They discovered a canal 15 feet (4.6 m) deep and 55 feet (17 m) wide running through Loulan from northwest to southeast, a 32-foot (9.8 m) high earthen dome-shaped Buddhist stupa; and home 41 feet (12 m) long by 28 feet (8.5 m) wide, apparently for a Chinese official, housing 3 rooms and supported by wooden pillars. They also collected 797 objects from the area, including vessels of wood, bronze objects, jewellery and coins, and Mesolithic stone tools[43][44] Other reported (2003) finds in the area include additional mummies and burial grounds, ephedra sticks, a string bracelet that holds a hollowed jade stone, a leather pouch, a woolen loincloth, a wooden mask painted red and with large nose and teeth, boat-shaped coffins, a bow with arrows and a straw basket.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ In 126 BCE, the Chinese envoy, Zhang Qian described Loulan as a fortified city near the great salt lake or marsh known as Lop Nur. (Watson, Burton, trans. 1993. Records of the Grand Historian: Han Dynasty II - Revised Edition. Columbia University Press, New York, p. 233).

- ↑ Hulsewé, A. F. P. and Loewe, M. A. N. 1979. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty, p. 89. E. Brill, Leiden. ISBN 90-04-05884-2.

- ↑ Mallory and Mair (2000). pp. 81-87.

- 1 2 Mallory, J. P. & Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. London. pp. 181–188. ISBN 0-500-05101-1.

- ↑ Hill (2009), p. 88.

- ↑ Watson (1993), p. 140.

- ↑ Hill (2009), pp. 3, 7, 9, 11, 35, 37, 85-101.

- ↑ Hanshu Chapter 96a, translation from Hulsewé 1979.

- ↑ Historical Atlas of the Classical World, 500 BC--AD 600. Barnes & Noble Books. 2000. p. 2.24. ISBN 978-0-7607-1973-2.

- ↑ Hulsewé 1979, p. 86–87

- ↑ Hulsewé, A. F. P. (1979). China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. Brill. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-9004058842.

- ↑ Hulsewé 1979, p. 90.

- ↑ Hulsewé (1979), p. 90-91.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Makiko Onishi & Asanobu Kitamoto. "Hedin, the Man Who Solved the Mystery of the Wandering Lake: Lop Nor and Lou-lan". Digital Silk Road.

- ↑ Hulsewé 1979, p. 91-92

- ↑ Rafe de Crespigny (14 May 2014). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23-220 AD). Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9789047411840.

- ↑ Mallory, J. P. & Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. London. p. 86. ISBN 0-500-05101-1.

- ↑ Charles F.W. Higham, ed. (2004). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilization. Fact on Files, Inc. pp. 309–311. ISBN 0-8160-4640-9.

- ↑ Annotated translation of the Weilüe by John E. Hill

- ↑ Baumer, Christoph. (2000), pp. 125-126, 135-136. Southern Silk Road: In the Footsteps of Sir Aurel Stein and Sven Hedin. Bangkok, White Orchid Books.

- ↑ Weishu Original text: 真君三年,鄯善王比龍避沮渠安周之難,率國人之半奔且末,後役屬鄯善。 Translation: In the third year of Zhenjun, the Loulan king Bilong, so as to avoid troubles from Juqu Anzhou, led half his countrymen and fled to Qiemo, which later controlled Shanshan.

- ↑ Da Tang Xiyu Ji Original text: 从此东行六百余里至折摩驮那故国。即涅末地也。城郭岿然人烟断绝。复此东北行千余里至纳缚波故国。即楼兰地也。

- ↑ Hulsewé (1979), p. 86.

- ↑ Hulsewé (1979), p. 83.

- ↑ Hulsewé (1979), p. 85.

- ↑ Shui Jing Zhu

- ↑ James Legge (1886). Fa-Hien's Record Of Buddistic Kingdoms. Oxford University Press Warehouse. pp. 12–15.

- ↑ Tucker, Jonathan (18 December 2013). The Silk Road - China and the Karakorum Highway: A Travel Companion. I.B.Tauris. p. 162. ISBN 978-1780763569.

- ↑ Mallory, J.P. "Bronze Age languages of the Tarim Basin" (PDF). Expedition. 52 (3): 44–53.

- 1 2 3 4 Padwa, Mariner (August 2004). Susan Whitfield and Ursula Sims-Williams, eds. The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. British Library. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-1932476132.

- 1 2 Valerie Hansen (2012). "Chapter 1: At the Crossroads of Central Asia - The Kingdom of Kroraina". The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 26. ISBN 978-0195159318.

- 1 2 J. P. Mallory (November 2015). "The Problem of Tocharian Origins: An Archaeological Perspective" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers (259): 6.

- ↑ Kazuo Enoki (1998), "Yü-ni-ch’êng and the Site of Lou-Lan," and "The Location of the Capital of Lou-Lan and the Date of the Kharoshthi Inscriptions," in Rokuro Kono (ed), Studia Asiatica: The Collected Papers in Western Languages of the Late Dr. Kazuo Enoki, Tokyo: Kyu-Shoin, pp 200, 211–57.

- ↑ Mallory, J. P. & Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. London. p. 81. ISBN 0-500-05101-1.

- ↑ Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, pp 20-21 footnote #38, ISSN 2157-9687.

- ↑ Howard, Michael C. (2012), Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies, the Role of Cross Border Trade and Travel, McFarland & Company, p. 134.

- ↑ Hansen, Valerie (2012), The Silk Road: A New History, Oxford University Press, p. 98, ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- ↑ Galambos, Imre (2015), "She Association Circulars from Dunhuang", in Antje Richter, A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture, Leiden & Boston: Brill, pp 870–72.

- ↑ Hedin, Sven (1898). Through Asia. London: Methuen & Co.

- ↑ Christoph Baumer. "Explorer Club Flag 60 report" (PDF). The Explorers Club. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Unclosed the Mystery of the Ancient City LK". travel-silkroad.com.

- ↑ Ma Dazheng. An Overview of 20th Century Xinjiang Explorations. Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Web site, 2003 May 22

- ↑ "Loulan vanished in sand". Washington Times. 2005-01-13.

- ↑ Mallory, J. P. & Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. London. ISBN 0-500-05101-1.

References

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hulsewé, A. F. P. (1979). China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. E. Brill, Leiden. ISBN 978-9004058842.

- Mallory, J. P. and Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. London. ISBN 0-500-05101-1.

- Watson, Burton, trans. (1993). Records of the Grand Historian: Han Dynasty II - Revised Edition. Columbia University Press, New York. ISBN 0-231-08166-9 and ISBN 0-231-08167-7.

Further reading

- Ma Dazheng. 2003. The Tarim Basin. Ch. 7 in: History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Volume 5: Development in contrast: from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. Edited by Chahryar Adle and Irfan Habib. UNESCO Publications.

External links

- Downloadable article: "Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age" Li et al. BMC Biology 2010, 8:15.

- Loulan, vanished in sand

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Loulan. |