Kosovo

Coordinates: 42°35′N 21°00′E / 42.583°N 21.000°E

| Republic of Kosovo | |

|---|---|

Location and extent of Kosovo in Europe. | |

| Status |

Disputed Recognized by 111 UN member states and the United Nations, but claimed by Serbia as the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija |

| Capital and largest city |

Pristina 42°40′N 21°10′E / 42.667°N 21.167°E |

| Official languages | |

| Recognised regional languages | |

| Demonym |

|

| Government | Unitary Parliamentary republic |

| Hashim Thaçi | |

| Isa Mustafa | |

| Legislature | Assembly of Kosovo |

| Establishment | |

| 1877 | |

| 31 January 1946 | |

| 2 July 1990 | |

| 10 June 1999 | |

| June 1999 | |

| 17 February 2008 | |

| 10 September 2012 | |

| 19 April 2013 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 10,908 km2 (4,212 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 1.0[2] |

| Population | |

• 2014 estimate | 1,859,203a[3] |

• 2011 census | 1,739,825b |

• Density | 159/km2 (411.8/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2016 estimate |

• Total | $18.840 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $10,134 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2016 estimate |

• Total | $8.315 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $4,472 |

| Gini (FY2005/2006) |

30.0[5] medium · 121 |

| HDI (2013) |

high |

| Currency | Euro (€)c (EUR) |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) |

| CEST (UTC+2) | |

| Drives on the | right |

| Calling code | +383d |

| ISO 3166 code | XK |

| |

Kosovo (/ˈkɒsəvoʊ, ˈkoʊ-/;[8] Albanian: Kosova, [kɔsɔva] or Kosovë; Serbian Cyrillic: Косово) is a disputed territory[9][10] and partially recognised state[11][12] in Southeastern Europe that declared independence from Serbia in February 2008 as the Republic of Kosovo (Albanian: Republika e Kosovës; Serbian: Република Косово/Republika Kosovo).

Kosovo is landlocked in the central Balkan Peninsula. With its strategic position in the Balkans, it serves as an important link in the connection between central and southern Europe, the Adriatic Sea, and Black Sea. Its capital and largest city is Pristina, and other major urban areas include Prizren, Peć and Gjakova. It is bordered by Albania to the southwest, the Republic of Macedonia to the southeast, Montenegro to the west and the uncontested territory of Serbia to the north and east. While Serbia recognises administration of the territory by Kosovo's elected government,[13] it continues to claim it as its own Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija.

Kosovo's history dates back to the Paleolithic age, represented by the Vinča and Starčevo cultures. During the Classical period, it was inhabited by the Illyrian-Dardanian and Celtic people. In 168 BC, the area was annexed by the Romans.[14] In the Middle Ages, the country was conquered by the Byzantine, Bulgarian and Serbian Empires. The Battle of Kosovo of 1389 is considered to be one of the defining moments in Serbian medieval history. The country was the core of the Serbian medieval state, which has also been the seat of the Serbian Orthodox Church from the 14th century, when its status was upgraded into a patriarchate.[15][16]

Kosovo was part of the Ottoman Empire from the 15th to the early 20th century. In the late 19th century, Kosovo became the centre of the Albanian national awakening. Following their defeat in the Balkan Wars, the Ottomans ceded Kosovo to Serbia and Montenegro. Both countries joined Yugoslavia after World War I, and following a period of Yugoslav unitarianism in the Kingdom, the post-World War II Yugoslav constitution established the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija within the Yugoslav constituent Republic of Serbia. Tensions between Kosovo's Albanian and Serb communities simmered through the 20th century and occasionally erupted into major violence, culminating in the Kosovo War of 1998 and 1999, which resulted in withdrawal of Serbian armed forces and establishment of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo. On 17 February 2008, Kosovo unilaterally declared its independence from Serbia. It has since gained diplomatic recognition as a sovereign state by 111 UN member states, Serbia refuses to recognize Kosovo as a state.[17] although with the Brussels Agreement of 2013, it has accepted the legitimacy of its institutions. Kosovo has a lower-middle-income economy and has experienced solid economic growth over the last decade by international financial institutions, and has experienced growth every year since the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008.[18]

Etymology

The entire region is commonly referred to in English simply as Kosovo and in Albanian as Kosova (definite form, [kɔˈsɔːva]) or Kosovë ("indefinite" form, [kɔˈsɔːv]). In Serbia, a formal distinction is made between the eastern and western areas; the term Kosovo (Косово) is used for the eastern part centred on the historical Kosovo Field, while the western part is called Metohija (Метохија) (known as Dukagjini in Albanian).[19]

Kosovo (Serbian Cyrillic: Косово, [kôsoʋo]) is the Serbian neuter possessive adjective of kos (кос) "blackbird", an ellipsis for Kosovo Polje, 'blackbird field', the name of a plain situated in the eastern half of today's Kosovo and the site of the 1389 Battle of Kosovo Field.[20] The name of the plain was applied to the Kosovo Province created in 1864.

Albanians also refer to Kosovo as Dardania, the name of a Roman province formed in 165 BC, which covered the territory of modern Kosovo. The name is derived from ancient tribe of Dardani, ultimately from proto-Albanian word dardha/dardā which means "pear".[21] The former Kosovo President Ibrahim Rugova had been an enthusiastic backer of a "Dardanian" identity and the Kosovan flag and presidential seal refer to this national identity. However, the name "Kosova" remains more widely used among the Albanian population.

The current borders of Kosovo were drawn while part of SFR Yugoslavia in 1946, when the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija was created as an administrative division of the new Socialist Republic of Serbia. In 1974, the compositional "Kosovo and Metohija" was reduced to a simple "Kosovo" in the name of the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, but in 1990 the region was renamed the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija.[22]

The official conventional long name of the state is Republic of Kosovo, as defined by the Constitution of Kosovo, and is used to represent Kosovo internationally.[23] Additionally, as a result of an arrangement agreed between Pristina and Belgrade in talks mediated by the European Union, Kosovo has participated in some international forums and organisations under the title "Kosovo*" with a footnote stating "This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSC 1244 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence". This arrangement, which has been dubbed the "asterisk agreement", was agreed in an 11-point arrangement agreed on 24 February 2012.[24]

History

Early history

In prehistory, the succeeding Starčevo culture and Vinča culture were active in the region.[25] The area in and around Kosovo has been inhabited for nearly 10,000 years. During the Neolithic age, Kosovo lay within the area of the Vinča-Turdaş culture which is characterised by West Balkan black and grey pottery. Bronze and Iron Age tombs have been found in Metohija.[26]

The favorable Geo-strategic position as well as abundant natural resources were ideal for the development of life since the prehistoric periods, proven by hundreds of archaeological sites discovered and identified throughout Kosovo, which proudly present its rich archeological heritage.[27] The number of sites with archaeological potential is increasing, this as a result of findings and investigations that are carried out throughout Kosovo but also from many superficial traces which offer a new overview of antiquity of Kosovo.[27]

The earliest traces documented in the territory of Kosovo belong to the Stone Age Period, namely there are indications that cave dwellings might have existed like for example the Radivojce Cave set near the spring of the Drin river, then there are some indications at Grnčar Cave in the Vitina municipality, Dema and Karamakaz Caves of Peć and others. However, human settlement during the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age is not confirmed yet and not scientifically proven. Therefore, until arguments of Paleolithic and Mesolithic man are confirmed, Neolithic man, respectively the Neolithic sites are considered as the chronological beginning of population in Kosovo.

From this period until today Kosovo has been inhabited, and traces of activities of societies from prehistoric, ancient and up to medieval time are visible throughout its territory. Whereas, in some archaeological sites, multilayer settlements clearly reflect the continuity of life through centuries.[28]

During antiquity, the area which now makes up Kosovo was inhabited by various tribal ethnic groups, who were liable to move, enlarge, fuse and fissure with neighbouring groups. As such, it is difficult to locate any such group with precision. The Dardani, whose exact ethno-linguistic affiliation is difficult to determine, were a prominent group in the region during the late Hellenistic and early Roman eras.[29][30][31]

The area was then conquered by Rome in the 160s BC, and incorporated into the Roman province of Illyricum in 59 BC. Subsequently, it became part of Moesia Superior in AD 87. The region was exposed to an increasing number of 'barbarian' raids from the 4th century AD onwards, culminating with the Slavic migrations of the 6th and 7th centuries. Archaeologically, the early Middle Ages represent a hiatus in the material record,[32] and whatever was left of the native provincial population fused into the Slavs.[33]

Middle Ages

.png)

The subsequent political and demographic history of Kosovo is not known with absolute certainty until the 13th century. Archaeological findings suggest that there was steady population recovery and progression of the Slavic culture seen elsewhere throughout the Balkans. The region was absorbed into the Bulgarian Empire in the 850s, where Byzantine culture was cemented in the region. It was re-taken by the Byzantines after 1018, and became part of the newly established Theme of Bulgaria. As the centre of Slavic resistance to Constantinople in the region, the region often switched between Serbian and Bulgarian rule on one hand and Byzantine on the other, until Serbian Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja secured it by the end of the 12th century.[34] An insight into the region is provided by the Byzantine historian-princess, Anna Comnena, who wrote of "Serbs" being the "main" inhabitants of the region.[35]

The earliest reference of the Albanians comes from Michael Attaleiates, who spoke of the Arbanitai located around the hinterland districts of Dyrrachium (modern Durrës) on the Adriatic Sea.[36]

The zenith of Serbian power was reached in 1346, with the formation of the Serbian Empire. During the 13th and 14th centuries, Kosovo became a political, cultural and religious centre of the Serbian Kingdom. In the late 13th century, the seat of the Serbian Archbishopric was moved to Peć, and rulers centred themselves between Prizren and Skopje,[37] during which time thousands of Christian monasteries and feudal-style forts and castles were erected.[38] Stefan Dušan used Prizren Fortress as the capital of the Empire. When the Serbian Empire fragmented into a conglomeration of principalities in 1371, Kosovo became the hereditary land of the House of Branković. In the late 14th and the 15th centuries parts of Kosovo, the easternmost area of which was located near Pristina, were part of the Principality of Dukagjini, which was later incorporated into an anti-Ottoman federation of all Albanian principalities, the League of Lezhë.[39]

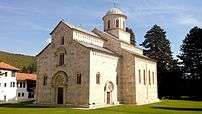

Medieval Monuments in Kosovo is a today combined UNESCO World Heritage Site consisting of four Serbian Orthodox churches and monasteries. The constructions were founded by members of Nemanjić dynasty, the most important dynasty of Serbia in the Middle Ages.[40]

In the 1389 Battle of Kosovo, Ottoman forces defeated a coalition led by Lazar Hrebeljanović.[41][42] Some historians, most notably Noel Malcolm argues that the battle of Kosovo in 1389 did not end with an Ottoman victory and "the Serbian statehood did survive for another seventy years."[43] Soon after, Lazar's son accepted Turkish nominal vassalage (as did some other Serbian principalities) and Lazar's daughter was married to the Sultan to seal the peace. By 1459, Ottomans conquered the new Serbian capital of Smederevo,[44] leaving Belgrade and Vojvodina under Hungarian rule until second quarter of the 16th century.

Kosovo was part of the Ottoman Empire from 1455 to 1912, at first as part of the eyalet of Rumelia, and from 1864 as a separate province (vilayet). During this time, Islam was introduced to the population. The Vilayet of Kosovo was an area much larger than today's Kosovo; it included all today's Kosovo territory, sections of the Sandžak region cutting into present-day Šumadija and Western Serbia and Montenegro along with the Kukës municipality, the surrounding region in present-day northern Albania and also parts of north-western Macedonia with the city of Skopje (then Üsküp), as its capital. Between 1881 and 1912 (its final phase), it was internally expanded to include other regions of present-day Republic of Macedonia, including larger urban settlements such as Štip (İştip), Kumanovo (Kumanova) and Kratovo (Kratova). Serbs likely formed a majority of Kosovo's from the 8th to the mid-19th century.[45][46] Some scholars, such as the historian Fredrick F. Anscombe, believe that medieval and Ottoman Kosovo was ethnically heterogeneous, with Serbs and Albanians dominating at different times.[47]

Kosovo was part of the wider Ottoman region to be occupied by Austrian forces during the Great War of 1683–99,[48] but the Ottomans re-established their rule of the region. Such acts of assistance by the Austrian Empire (then arch-rivals of the Ottoman Empire), or Russia, were always abortive or temporary at best.[49][50] In 1690, the Serbian Patriarch Arsenije III led thousands people from Kosovo to the Christian north, in what came to be known as the Great Serb Migration.[51][52] In 1766, the Ottomans abolished the Patriarchate of Peć and fully imposed the jizya on its non-Muslim population.

Although initially stout opponents of the advancing Turks, Albanian chiefs ultimately came to accept the Ottomans as sovereigns. The resulting alliance facilitated the mass conversion of Albanians to Islam. Given that the Ottoman Empire's subjects were divided along religious (rather than ethnic) lines, Islamisation greatly elevated the status of Albanian chiefs. Prior to this, they were organised along simple tribal lines, living in the mountainous areas of modern Albania (from Kruje to the Sar range).[53] Soon, they expanded into a depopulated Kosovo,[54] as well as northwestern Macedonia, although some might have been autochthonous to the region.[55] However, Banac favours the idea that the main settlers of the time were Vlachs.[49]

Many Albanians gained prominent positions in the Ottoman government. "Albanians had little cause of unrest", according to author Dennis Hupchik. "If anything, they grew important in Ottoman internal affairs."[56] In the 19th century, there was an awakening of ethnic nationalism throughout the Balkans. The underlying ethnic tensions became part of a broader struggle of Christian Serbs against Muslim Albanians.[42] The ethnic Albanian nationalism movement was centred in Kosovo. In 1878 the League of Prizren (Lidhja e Prizrenit) was formed. This was a political organisation that sought to unify all the Albanians of the Ottoman Empire in a common struggle for autonomy and greater cultural rights,[57] although they generally desired the continuation of the Ottoman Empire.[58] The League was dis-established in 1881 but enabled the awakening of a national identity among Albanians.[59] Albanian ambitions competed with those of the Serbs. The Kingdom of Serbia wished to incorporate this land that had formerly been within its empire.

During and after the Serbian–Ottoman War of 1876–78, between 30,000 and 70,000 Muslims, mostly Albanians, were expelled from the Sanjak of Niš and fled to the Kosovo Vilayet.[60][61][62][63][64][65]

Yugoslavia

The Young Turk movement took control of the Ottoman Empire after a coup in 1912 which deposed Sultan Abdul Hamid II. The movement supported a centralised form of government and opposed any sort of autonomy desired by the various nationalities of the Ottoman Empire. An allegiance to Ottomanism was promoted instead.[66] An Albanian uprising in 1912 exposed the empire's northern territories in Kosovo and Novi Pazar, which led to an invasion by the Kingdom of Montenegro. The Ottomans suffered a serious defeat at the hands of Albanians in 1912, culminating in the Ottoman loss of most of its Albanian-inhabited lands. The Albanians threatened to march all the way to Salonika and reimpose Abdul Hamid.[67]

A wave of Albanians in the Ottoman army ranks also deserted during this period, refusing to fight their own kin. In September 1912, a joint Balkan force made up of Serbian, Montenegrin, Bulgarian and Greek forces drove the Ottomans out of most of their European possessions. The rise of nationalism unfortunately hampered relations between Albanians and Serbs in Kosovo, due to influence from Russians, Austrians and Ottomans.[68] After the Ottomans' defeat in the First Balkan War, the 1913 Treaty of London was signed with Western Kosovo (Metohija) ceded to the Kingdom of Montenegro and Eastern Kosovo ceded to the Kingdom of Serbia.[69] Soon, there were concerted Serbian colonisation efforts in Kosovo during various periods between Serbia's 1912 takeover of the province and World War II. So the population of Serbs in Kosovo fell after World War II, but it had increased considerably before then.[70]

An exodus of the local Albanian population occurred. Serbian authorities promoted creating new Serb settlements in Kosovo as well as the assimilation of Albanians into Serbian society.[71] Numerous colonist Serb families moved into Kosovo, equalising the demographic balance between Albanians and Serbs.

In the winter of 1915–16, during World War I, Kosovo saw the retreat of the Serbian army as Kosovo was occupied by Bulgaria and Austria-Hungary. In 1918, the Allied Powers pushed the Central Powers out of Kosovo. After the end of World War I, the Kingdom of Serbia was transformed into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians on 1 December 1918.

Kosovo was split into four counties, three being a part of Serbia (Zvečan, Kosovo and southern Metohija) and one of Montenegro (northern Metohija). However, the new administration system since 26 April 1922 split Kosovo among three districts (oblast) of the Kingdom: Kosovo, Raška and Zeta. In 1929, the country was transformed into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the territories of Kosovo were reorganised among the Banate of Zeta, the Banate of Morava and the Banate of Vardar. In order to change the ethnic composition of Kosovo, between 1912 and 1941 a large-scale Serbian re-colonisation of Kosovo was undertaken by the Belgrade government. Meanwhile, Kosovar Albanians' right to receive education in their own language was denied alongside other non-Slavic or unrecognised Slavic nations of Yugoslavia, as the kingdom only recognised the Slavic Croat, Serb, and Slovene nations as constituent nations of Yugoslavia, while other Slavs had to identify as one of the three official Slavic nations while non-Slav nations were only deemed as minorities.[71]

Albanians and other Muslims were forced to emigrate, mainly with the land reform which struck Albanian landowners in 1919, but also with direct violent measures.[72][73] In 1935 and 1938 two agreements between the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Turkey were signed on the expatriation of 240,000 Albanians to Turkey, which was not completed because of the outbreak of World War II.[74]

After the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in 1941, most of Kosovo was assigned to Italian-controlled Albania, with the rest being controlled by Germany and Bulgaria. A three-dimensional conflict ensued, involving inter-ethnic, ideological, and international affiliations, with the first being most important. Nonetheless, these conflicts were relatively low-level compared with other areas of Yugoslavia during the war years, with one Serb historian estimating that 3,000 Albanians and 4,000 Serbs and Montenegrins were killed, and two others estimating war dead at 12,000 Albanians and 10,000 Serbs and Montenegrins.[75] An official investigation conducted by the Yugoslav government in 1964 recorded nearly 8,000 war-related fatalities in Kosovo between 1941 and 1945, 5,489 of whom were Serb and Montenegrin and 2,177 of whom were Albanian.[76] It is not disputed that between 1941 and 1945 tens of thousands of Serbs, mostly recent colonists, fled from Kosovo. Estimates range from 30,000 to 100,000.[77] There had been large-scale Albanian immigration from Albania to Kosovo which is by some scholars estimated in the range from 72,000[78][79] to 260,000 people (with a tendency to escalate, the last figure being in a petition of 1985). Some historians and contemporary references emphasize that a large-scale migration of Albanians from Albania to Kosovo is not recorded in Axis documents.[80]

Communist Yugoslavia

The province as in its outline today first took shape in 1945 as the Autonomous Kosovo-Metohian Area. Until World War II, the only entity bearing the name of Kosovo had been a political unit carved from the former vilayet which bore no special significance to its internal population. In the Ottoman Empire (which previously controlled the territory), it had been a vilayet with its borders having been revised on several occasions. When the Ottoman province had last existed, it included areas which were by now either ceded to Albania, or found themselves within the newly created Yugoslav republics of Montenegro, or Macedonia (including its previous capital, Skopje) with another part in the Sandžak region of southwest Serbia.

Tensions between ethnic Albanians and the Yugoslav government were significant, not only due to ethnic tensions but also due to political ideological concerns, especially regarding relations with neighbouring Albania.[81] Harsh repressive measures were imposed on Kosovo Albanians due to suspicions that there were sympathisers of the Stalinist regime of Enver Hoxha of Albania.[81] In 1956, a show trial in Pristina was held in which multiple Albanian Communists of Kosovo were convicted of being infiltrators from Albania and were given long prison sentences.[81] High-ranking Serbian communist official Aleksandar Ranković sought to secure the position of the Serbs in Kosovo and gave them dominance in Kosovo's nomenklatura.[82]

Islam in Kosovo at this time was repressed and both Albanians and Muslim Slavs were encouraged to declare themselves to be Turkish and emigrate to Turkey.[81] At the same time Serbs and Montenegrins dominated the government, security forces, and industrial employment in Kosovo.[81] Albanians resented these conditions and protested against them in the late 1960s, accusing the actions taken by authorities in Kosovo as being colonialist, as well as demanding that Kosovo be made a republic, or declaring support for Albania.[81]

After the ouster of Ranković in 1966, the agenda of pro-decentralisation reformers in Yugoslavia, especially from Slovenia and Croatia, succeeded in the late 1960s in attaining substantial decentralisation of powers, creating substantial autonomy in Kosovo and Vojvodina, and recognising a Muslim Yugoslav nationality.[83] As a result of these reforms, there was a massive overhaul of Kosovo's nomenklatura and police, that shifted from being Serb-dominated to ethnic Albanian-dominated through firing Serbs in large scale.[83] Further concessions were made to the ethnic Albanians of Kosovo in response to unrest, including the creation of the University of Pristina as an Albanian language institution.[83] These changes created widespread fear among Serbs that they were being made second-class citizens in Yugoslavia.[84] By the 1974 Constitution of Yugoslavia, Kosovo was granted major autonomy, allowing it to have its own administration, assembly, and judiciary; as well as having a membership in the collective presidency and the Yugoslav parliament, in which it held veto power.[85]

In the aftermath of the 1974 constitution, concerns over the rise of Albanian nationalism in Kosovo rose with the widespread celebrations in 1978 of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the League of Prizren.[81] Albanians felt that their status as a "minority" in Yugoslavia had made them second-class citizens in comparison with the "nations" of Yugoslavia and demanded that Kosovo be a constituent republic, alongside the other republics of Yugoslavia.[86] Protests by Albanians in 1981 over the status of Kosovo resulted in Yugoslav territorial defence units being brought into Kosovo and a state of emergency being declared resulting in violence and the protests being crushed.[86] In the aftermath of the 1981 protests, purges took place in the Communist Party, and rights that had been recently granted to Albanians were rescinded – including ending the provision of Albanian professors and Albanian language textbooks in the education system.[86]

Due to very high birth rates, the proportion of Albanians increased from 75% to over 90%. In contrast, the number of Serbs barely increased, and in fact dropped from 15% to 8% of the total population, since many Serbs departed from Kosovo as a response to the tight economic climate and increased incidents with their Albanian neighbours. While there was tension, charges of "genocide" and planned harassment have been debunked as an excuse to revoke Kosovo's autonomy. For example, in 1986 the Serbian Orthodox Church published an official claim that Kosovo Serbs were being subjected to an Albanian program of 'genocide'.[87]

Even though they were disproved by police statistics,[87] they received wide attention in the Serbian press and that led to further ethnic problems and eventual removal of Kosovo's status. Beginning in March 1981, Kosovar Albanian students of the University of Pristina organised protests seeking that Kosovo become a republic within Yugoslavia and demanding their human rights.[88] The protests were brutally suppressed by the police and army, with many protesters arrested.[89] During the 1980s, ethnic tensions continued with frequent violent outbreaks against Yugoslav state authorities, resulting in a further increase in emigration of Kosovo Serbs and other ethnic groups.[90][91] The Yugoslav leadership tried to suppress protests of Kosovo Serbs seeking protection from ethnic discrimination and violence.[92]

Kosovo War

Inter-ethnic tensions continued to worsen in Kosovo throughout the 1980s. In 1989, Serbian President Slobodan Milošević, employing a mix of intimidation and political manoeuvring, drastically reduced Kosovo's special autonomous status within Serbia and started cultural oppression of the ethnic Albanian population.[93] Kosovo Albanians responded with a non-violent separatist movement, employing widespread civil disobedience and creation of parallel structures in education, medical care, and taxation, with the ultimate goal of achieving the independence of Kosovo.[94]

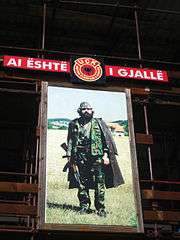

In July 1990, the Kosovo Albanians proclaimed the existence of the Republic of Kosova, and declared it a sovereign and independent state in September 1992.[95] In May 1992, Ibrahim Rugova was elected its president in an election in which only Kosovo Albanians participated.[96] During its lifetime, the Republic of Kosova was only officially recognised by Albania. By the mid-1990s, the Kosovo Albanian population was growing restless, as the status of Kosovo was not resolved as part of the Dayton Agreement of November 1995, which ended the Bosnian War. By 1996, the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), an ethnic Albanian guerrilla paramilitary group that sought the separation of Kosovo and the eventual creation of a Greater Albania,[lower-alpha 1] had prevailed over the Rugova's non-violent resistance movement and launched attacks against the Yugoslav Army and Serbian police in Kosovo, resulting in the Kosovo War.[93][102]

By 1998, international pressure compelled Yugoslavia to sign a ceasefire and partially withdraw its security forces. Events were to be monitored by Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) observers according to an agreement negotiated by Richard Holbrooke. The ceasefire did not hold and fighting resumed in December 1998, culminating in the Račak massacre, which attracted further international attention to the conflict.[93] Within weeks, a multilateral international conference was convened and by March had prepared a draft agreement known as the Rambouillet Accords, calling for the restoration of Kosovo's autonomy and the deployment of NATO peacekeeping forces. The Yugoslav delegation found the terms unacceptable and refused to sign the draft. Between 24 March and 10 June 1999, NATO intervened by bombing Yugoslavia aimed to force Milošević to withdraw his forces from Kosovo,[103] though NATO could not appeal to any particular motion of the Security Council of the United Nations to help legitimise its intervention.

.jpg)

Combined with continued skirmishes between Albanian guerrillas and Yugoslav forces the conflict resulted in a further massive displacement of population in Kosovo.[104]

During the conflict, roughly a million ethnic Albanians fled or were forcefully driven from Kosovo. In 1999 more than 11,000 deaths were reported to the office of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia prosecutor Carla Del Ponte.[105] As of 2010, some 3,000 people were still missing, of which 2,500 are Albanian, 400 Serbs and 100 Roma.[106] By June, Milošević agreed to a foreign military presence in Kosovo and the withdrawal of his troops. After the Yugoslav Army withdrew, over half of Kosovo's Serbs and other non-Albanians flew or were expelled and many of the remaining civilians were subjected to abuse.[107][107][108][109][110][111] During the Kosovo War, over 90,000 Serbian and other non-Albanian refugees fled the war-torn province. In the days after the Yugoslav Army withdrew, over 200,000 (over half) Serb and other non-Albanians civilians were expelled from Kosovo and many of the remaining civilians were victims of abuse.[112][113][114][115][111] After Kosovo and other Yugoslav Wars, Serbia became home to the highest number of refugees and IDPs (including Kosovo Serbs) in Europe.[116][117][118]

In some villages under Albanian control in 1998, militants drove ethnic-Serbs from their homes. Some of those who remained are unaccounted for and are presumed to have been abducted by the KLA and killed. The KLA detained an estimated 85 Serbs during its 19 July 1998 attack on Orahovac. 35 of these were subsequently released but the others remained. On 22 July 1998, the KLA briefly took control of the Belaćevac mine near the town of Obilić. Nine Serb mineworkers were captured that day and they remain on the International Committee of the Red Cross's list of the missing and are presumed to have been killed.[107] In August 1998, 22 Serbian civilians were reportedly killed in the village of Klečka, where the police claimed to have discovered human remains and a kiln used to cremate the bodies.[107][119] In September 1998, Serbian police collected 34 bodies of people believed to have been seized and murdered by the KLA, among them some ethnic Albanians, at Lake Radonjić near Glođane (Gllogjan) in what became known as the Lake Radonjić massacre.[107]

During and after the 1999 war, over three hundred Serb civilians who were taken across the border into Albania were killed in a "Yellow House" near the town of Burrel and had several of their organs removed for sale on the black market. These claims were investigated first by the ICTY who found medical equipment and traces of blood in and around the house.[120] They were then investigated by the UN, who received witness reports from many ex-UK fighters who stated that several of the prisoners had their organs removed.[121] Chief Prosecutor for the ICTY; Carla Del Ponte revealed these crimes to the public in her book; Madame Prosecutor in 2008, causing a large response. In 2011; French media outlet; France24 released a classified UN document written in 2003 which documented the crimes.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) prosecuted crimes committed during the Kosovo War. Nine senior Yugoslav officials, including Milošević, were indicted for crimes against humanity and war crimes committed between January and June 1999. Six of the defendants were convicted, one was acquitted, one died before his trial could commence, and one (Milošević) died before his trial could conclude.[122] Six KLA members were charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes by the ICTY following the war, but only one was convicted.[123][124][125][126]

Post-war

On 10 June 1999, the UN Security Council passed UN Security Council Resolution 1244, which placed Kosovo under transitional UN administration (UNMIK) and authorised Kosovo Force (KFOR), a NATO-led peacekeeping force. Resolution 1244 provided that Kosovo would have autonomy within the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and affirmed the territorial integrity of Yugoslavia, which has been legally succeeded by the Republic of Serbia.[127]

Estimates of the number of Serbs who left when Serbian forces left Kosovo vary from 65,000[128] to 250,000[129] (194,000 Serbs were recorded as living in Kosovo in the census of 1991. But many Roma also left and may be included in the higher estimates). The majority of Serbs who left were from urban areas, but Serbs who stayed (whether in urban or rural areas) suffered violence which largely (but not entirely) ceased between early 2001 and the riots of March 2004, and ongoing fears of harassment may be a factor deterring their return. International negotiations began in 2006 to determine the final status of Kosovo, as envisaged under UN Security Council Resolution 1244. The UN-backed talks, led by UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari, began in February 2006. Whilst progress was made on technical matters, both parties remained diametrically opposed on the question of status itself.[130]

In February 2007, Ahtisaari delivered a draft status settlement proposal to leaders in Belgrade and Pristina, the basis for a draft UN Security Council Resolution which proposed 'supervised independence' for the province. A draft resolution, backed by the United States, the United Kingdom and other European members of the Security Council, was presented and rewritten four times to try to accommodate Russian concerns that such a resolution would undermine the principle of state sovereignty.[131]

Russia, which holds a veto in the Security Council as one of five permanent members, had stated that it would not support any resolution which was not acceptable to both Belgrade and Kosovo Albanians.[132] Whilst most observers had, at the beginning of the talks, anticipated independence as the most likely outcome, others have suggested that a rapid resolution might not be preferable.[133]

After many weeks of discussions at the UN, the United States, United Kingdom and other European members of the Security Council formally 'discarded' a draft resolution backing Ahtisaari's proposal on 20 July 2007, having failed to secure Russian backing. Beginning in August, a "Troika" consisting of negotiators from the European Union (Wolfgang Ischinger), the United States (Frank G. Wisner) and Russia (Alexander Botsan-Kharchenko) launched a new effort to reach a status outcome acceptable to both Belgrade and Pristina. Despite Russian disapproval, the U.S., the United Kingdom, and France appeared likely to recognise Kosovar independence.[134] A declaration of independence by Kosovar Albanian leaders was postponed until the end of the Serbian presidential elections (4 February 2008). Most EU members and the US had feared that a premature declaration could boost support in Serbia for the ultra-nationalist candidate, Tomislav Nikolić.[135]

Provisional self-government

In November 2001, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe supervised the first elections for the Kosovo Assembly.[136] After that election, Kosovo's political parties formed an all-party unity coalition and elected Ibrahim Rugova as President and Bajram Rexhepi (PDK) as Prime Minister.[137] After Kosovo-wide elections in October 2004, the LDK and AAK formed a new governing coalition that did not include PDK and Ora. This coalition agreement resulted in Ramush Haradinaj (AAK) becoming Prime Minister, while Ibrahim Rugova retained the position of President. PDK and Ora were critical of the coalition agreement and have since frequently accused that government of corruption.[138]

Parliamentary elections were held on 17 November 2007. After early results, Hashim Thaçi who was on course to gain 35 per cent of the vote, claimed victory for PDK, the Democratic Party of Kosovo, and stated his intention to declare independence. Thaçi formed a coalition with current President Fatmir Sejdiu's Democratic League which was in second place with 22 percent of the vote.[139] The turnout at the election was particularly low. Most members of the Serb minority refused to vote.[140]

Independence

Kosovo declared independence from Serbia on 17 February 2008.[141] As of 27 February 2017, 111 UN states recognise its independence, including all of its immediate neighbours, with the exception of Serbia.[142] Since declaring independence, it has become a member of the international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank,[143][144] though not of the United Nations.

The Serb minority of Kosovo, which largely opposes the declaration of independence, has formed the Community Assembly of Kosovo and Metohija in response. The creation of the assembly was condemned by Kosovo's president Fatmir Sejdiu, while UNMIK has said the assembly is not a serious issue because it will not have an operative role.[145] On 8 October 2008, the UN General Assembly resolved, on a proposal by Serbia, to ask the International Court of Justice to render an advisory opinion on the legality of Kosovo's declaration of independence. The advisory opinion, which is not binding over decisions by states to recognise or not recognise Kosovo, was rendered on 22 July 2010, holding that Kosovo's declaration of independence was not in violation either of general principles of international law, which do not prohibit unilateral declarations of independence, nor of specific international law – in particular UNSCR 1244 – which did not define the final status process nor reserve the outcome to a decision of the Security Council.[146]

Some rapprochement between the two governments took place on 19 April 2013 as both parties reached the Brussels Agreement, an EU brokered agreement that would allow the Serb minority in Kosovo to have its own police force and court of appeals.[147] The agreement is yet to be ratified by either parliament.[148]

Environment

Geography

Kosovo has an area of 10,887 square kilometers.[149] It lies between latitudes 42° and 43° N, and longitudes 20° and 22° E. The border of Kosovo is approximately 702 km (436 miles) long. It borders Albania to the southwest (112 km), Macedonia to the southeast (159 km), Montenegro to the west (79 km), and Central Serbia to the north and east (352 km).[149]

Most of its terrain is mountainous; the highest peak is Đeravica with 2,656 m (8,714 ft). There are two main plain regions, the Metohija basin in the west, and the Plain of Kosovo in the east. The main rivers of the region are the White Drin, running towards the Adriatic Sea, the South Morava in the Goljak area, and Ibar in the north. Sitnica, a tributary of Ibar, is the longest river lying completely within Kosovo. The biggest lakes are Gazivoda, Radonjić, Batlava and Badovac. The largest cities are Pristina, the capital, with an estimated 198,000 inhabitants, Prizren on the southwest, with a population of 178,000, Peć in the west with 95,000 inhabitants, and Ferizaj in the south at around 108,000.

39.1% of Kosovo is forested, about 52% is classified as agricultural land, 31% of which is covered by pastures and 69% is arable.[150] Phytogeographically, Kosovo belongs to the Illyrian province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF and Digital Map of European Ecological Regions by the European Environment Agency, the territory of Kosovo belongs to the ecoregion of Balkan mixed forests. The 39,000 ha Šar Mountains National Park, established in 1986 along the border with the Republic of Macedonia, is the only national park in Kosovo, although the Balkan Peace Park in the Prokletije along the border with Montenegro has been proposed as another one.[151] The Nerodimka river, near Ferizaj, is the only example in Europe of a river dividing with its waters flowing into two different seas.[152]

- Geography of Kosovo

Section between Mountains of Irzniq in Peć, western part of Kosovo.

Section between Mountains of Irzniq in Peć, western part of Kosovo. View from the top of Ostrvica Mountain opposite the Šar Mountains.

View from the top of Ostrvica Mountain opposite the Šar Mountains. Mirusha Canyon at the fourth lake.

Mirusha Canyon at the fourth lake. Aerial view of Kosovo plain near the capital Pristina.

Aerial view of Kosovo plain near the capital Pristina.

Climate

Kosovo has a humid continental climate with Mediterranean and oceanic influences, featuring warm summers and cold and snowy winters. Precipitation ranges from 600 to 1,300 mm (24 to 51 in) per year, and is well distributed year-round. To the northeast, Kosovo field and Ibar river valley are drier (with total precipitation of about 600 millimetres (24 inches) per year) and more influenced by continental air masses, with colder winters and very hot summers. In the southwest, climatic area of Metohija receives more Mediterranean influences with warmer summers, somewhat higher precipitation (700 mm (28 in)) and heavy snowfalls in the winter. Mountainous areas of Prokletije in the west, Šar Mountains on the south and Kopaonik in the north have a more alpine climate, with high precipitation (900 to 1,300 mm (35 to 51 in) per year), short and fresh summers, and cold winters.[153] The average annual temperature of Kosovo is 9.5 °C (49.1 °F). The warmest month is July with average temperature of 19.2 °C (66.6 °F), and the coldest is January with −1.3 °C (29.7 °F). Except Prizren and Istok, all other meteorological stations in January recorded average temperatures under 0 °C (32 °F).[154]

- Climate of Kosovo

- Autumn in Peć

Warm temperature in Rugova mountains

Warm temperature in Rugova mountains

Snow in Prizren

Snow in Prizren

Biodiversity

The flora and fauna of Kosovo forests is quite rich due to the exposure to Mediterranean climate through the White Drin valley.[155] In that context, the Šar Mountains and the Prokletije are the two most important areas of the biodiversity.[156]:2 The woodlands of Sharr are habitat to 86 vascular plants of international significance, while the Prokletije house 128 endemic species.[156]:9 The flora is represented by 139 orders classified in 63 families, 35 genera and 20 species.[156]:2 It has a significance for the entire region of Balkans – although Kosovo represents only 2.3% of the entire surface of Balkans, in terms of vegetation it represents 25% of the Balkans flora and about 18% of the European flora.[156]:8 The fauna is composed of a wide range of species due to its relief, ecological factors and geographic location. The forests with the greatest varieties are the ones located in the Šar, Prokletije, Kopaonik and Mokna.[156]:14

- Biodiversity of Kosovo

- Flowers of Pistacia terebinthus are characteristic to the forests of Kosovo.

The Balkan lynx subspecies is found in Kosovo.

The Balkan lynx subspecies is found in Kosovo..jpg) Kosovo’s lakes and swamps are important resting places for the golden eagle.

Kosovo’s lakes and swamps are important resting places for the golden eagle.- Taxus baccata is rare in the Balkans, but still found in Kosovo.

Politics

Government

.jpg)

|

|

| Hashim Thaçi President |

Isa Mustafa Prime Minister |

Kosovo is a multi-party parliamentary representative democratic republic. The country is governed by legislative, executive and judicial institutions which derive from the Constitution which was adopted in June 2008, although until the Brussels Agreement, North Kosovo was in practice largely controlled by institutions of the Republic of Serbia or parallel institutions funded by Serbia. The Legislative is vested in both the Parliament and the ministers within their competencies. The Government exercises the executive power and is composed of the Prime Minister as the head of government, the deputy prime ministers, and the ministers of the various ministries.

The Judiciary is composed of the Supreme Court and subordinate courts, a Constitutional Court, and independent prosecutorial institutions. There also exist multiple independent institutions defined by the Constitution and law, as well as local governments. It specifies that the country is a secular state and neutral in matters of religious beliefs. Freedom of belief, conscience and religion is guaranteed with religious autonomy ensured and protected. All citizens are equal before the law and gender equality is ensured by the constitution.[157][158] The Constitutional Framework guarantees a minimum of ten seats in the 120-member Assembly for Serbs, and ten for other minorities, and also guarantees Serbs and other minorities places in the Government.

The President (Presidenti) serves as the head of state and represents the unity of the people, elected every five years, indirectly by the National Assembly, in a secret ballot by a two thirds majority of all deputies of the Assembly. The president invested primarily with representative responsibilities and powers. The head of state has the power to return draft legislation to the Assembly for reconsideration, and has a role in foreign affairs and certain official appointments.[159] The current President is Hashim Thaçi since 2016.

The Prime Minister (Kryeministri) serves as the head of government elected by the National Assembly. Ministers are nominated by the Prime Minister, and then confirmed by the Assembly. The Prime Minister is the leader of the party with the most seats in the National Assembly. The head of government exercises executive power of the country. The current Prime Minister is Isa Mustafa. His government consists of Albanians, as well as ministers from Kosovo's minorities, which include Bosniaks, Turks and Serbs.

Foreign relations and military

.jpg)

Foreign relations are conducted through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Pristina. The current minister is Enver Hoxhaj. As of 2017, 111 out of 193 UN member countries recognise the Republic of Kosovo. The nation is member of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the International Road and Transport Union (IRU), the Regional Cooperation Council, the Council of Europe Development Bank, the Venice Commission and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.[160] It has gained full membership in many major sports federations. Within the European Union, it is recognised by 23 of the 28 members and is a potential candidate for the future enlargement of the European Union.[161][162] In November 2015, Kosovo's bid to become a member of UNESCO but fell three votes short of the two-third majority required to join.[163][164] Almost 21 countries maintain embassies in Kosovo.[165] The Republic of Kosovo maintains 24 embassies[166] and 28 consular missions abroad.[167]

The relations with Albania are in a special case, considering that the two countries share the same language. The Albanian language is one of the official languages of Kosovo. Albania has an embassy in the capital Pristina and Kosovo an embassy in Tirana. In 1992, Albania was the only country whose parliament voted to recognise the Republic of Kosova. Albania was one of the first countries to officially announce its recognition of the sovereign Republic of Kosovo in February 2008.

The Global Peace Index 2015 ranked Kosovo 69th out of 163 countries. The President holds the title of commander-in-chief of the national armed forces. The current Minister of Security Forces is Haki Demolli. Citizens over the age of 18 are eligible to serve in the Kosovo Security Force. Members of the force are protected from discrimination on the basis of gender or ethnicity.[168] The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) led the Kosovo Force (KFOR) and the Kosovo Protection Corps (KPC) in 2008, started preparations for the formation of the Kosovo Security Force. In 2014, the former Prime Minister Hashim Thaçi declared, that the National Government had decided to establish a Defence Ministry in 2019, officially transform the Kosovo Security Forces into the Kosovan Armed Forces, an Army which meets all the standards of NATO members with the aim to join the alliance in the future.[169]

Law

The judicial system of Kosovo is a civil law system divided between courts with regular civil and criminal jurisdiction and administrative courts with jurisdiction over litigation between individuals and the public administration. As of the Constitution of Kosovo, the judicial system is composed of the Supreme Court, which is the highest judicial authority, a Constitutional Court, and an independent prosecutorial institution. All of them are administered by the Judicial Council located in Pristina. The Kosovo Police is the main state law enforcement agency in the nation. After the Independence of Kosovo in 2008, the force became the governmental agency. The agency carries nearly all general police duties such as criminal investigation, patrol activity, traffic policing, border control.

The Ahtisaari Plan envisaged two forms of international supervision of Kosovo after its independence such as the International Civilian Office (ICO), which would monitor the implementation of the Plan and would have a wide range of veto powers over legislative and executive actions, and the European Union Rule of Law Mission to Kosovo (EULEX), which would have the narrower mission of deploying police and civilian resources with the aim of developing the Kosovo Police and judicial systems but also with its own powers of arrest and prosecution. The declaration of independence and subsequent Constitution granted these bodies the powers assigned to them by the Ahtisaari Plan. Since the Plan was not voted on by the UN Security Council, the ICO's legal status within Kosovo was dependent on the de facto situation and Kosovo legislation; it was supervised by an International Steering Group (ISG) composed of the main states which recognised Kosovo. It was never recognised by Serbia or other non-recognising states. EULEX was also initially opposed by Serbia, but its mandate and powers were accepted in late 2008 by Serbia and the UN Security Council as operating under the umbrella of the continuing UNMIK mandate, in a status-neutral way, but with its own operational independence. The ICO's existence terminated on 10 September 2012, after the ISG had determined that Kosovo had substantially fulfilled its obligations under the Ahtisaari Plan. EULEX continues its existence under both Kosovo and international law; in 2012 the Kosovo president formally requested a continuation of its mandate until 2014.

Minorities

The relations between Kosovo-Albanians and Serbs have been hostile since the rise of nationalism in the Balkans during the 19th century.[170] During Communism in Yugoslavia, the ethnic Albanians and Serbs were strongly irreconcilable with sociological studies during the Tito-era indicating that ethnic Albanians and Serbs rarely accepted each other as neighbours or friends and few held interethnic marriages.[171] Ethnic prejudices, stereotypes and mutual distrust between ethnic Albanians and Serbs have remained common for decades.[171] The level of intolerance and separation between both communities during the Tito-period was reported by sociologists to be worse than that of Croat and Serb communities in Yugoslavia which also had tensions but held some closer relations between each other.[171]

Despite their planned integration into the Kosovar society and their recognition in the Kosovar constitution, the Romani, Ashkali, and Egyptian communities continue to face many difficulties, such as segregation and discrimination, in housing, education, health, employment and social welfare.[172] Many camps around Kosovo continue to house thousands of Internally Displaced People, all of whom are from minority groups and communities.[173] Because many of the Roma are believed to have sided with the Serbs during the conflict, taking part in the widespread looting and destruction of Albanian property, Minority Rights Group International report that Romani people encounter hostility by Albanians outside their local areas.[174]

Administration

%2C_administrative_divisions_-_Nmbrs_-_colored.svg.png)

Until 2007, Kosovo was divided into 30 municipalities. It is currently subdivided into seven districts and divided into 38, according to Kosovo law and the Brussels Agreement of 2013, which stipulated the formation of new municipalities with Serb majority populations. These municipalities, 10 altogether, are in the process of forming a community encompassing approximately 90% of the Serb population in Kosovo.[175]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Demographics

Population

.png)

According to the Kosovo in Figures 2005 Survey of the Statistical Office of Kosovo,[176][177][178] Kosovo's total population is estimated between 1.9 and 2.2 million with the following ethnic composition: Albanians 92%, Serbs 4%, Bosniaks and Gorans 2%, Turks 1%, Roma 1%. CIA World Factbook estimates the following ratio: 88% Albanians, 8% Kosovo Serbs and 4% other ethnic groups.[149] According to CIA The World Factbook estimated data from July 2009, Kosovo's population stands at 1,804,838 persons. It stated that ethnic composition is "Albanians 88%, Serbs 7%, other 5% (Bosniak, Gorani, Roma, Turk, Ashkali, Egyptian, Janjevci – Croats)".[149]

Albanians, steadily increasing in number, have constituted a majority in Kosovo since the 19th century, the earlier ethnic composition being disputed. Kosovo's political boundaries do not quite coincide with the ethnic boundary by which Albanians compose an absolute majority in every municipality; for example, Serbs form a local majority in North Kosovo and two other municipalities, while there are large areas with an Albanian majority outside of Kosovo, namely in the neighbouring regions of former Yugoslavia: the north-west of Macedonia, and in the Preševo Valley in Southern Serbia.

At 1.3% per year (2008 data), ethnic Albanians in Kosovo have the fastest rate of growth in population in Europe.[179] Over an 82-year period (1921–2003) the population of Kosovo grew to 460% of its original size. Whereas Albanians constituted 60% of Kosovo's 500,000 person population in 1931, by 1991 they reached 81% of Kosovo's 2 million person population.[180] In the second half of the 20th century, Kosovo Albanians had three times higher birth rates than Serbs.[181] In addition, most of Kosovo's pre-1999 Serb population relocated to Serbia proper following the ethnic cleansing campaign in 1999.[111]

Language

According to the Constitution, Albanian and Serbian are the official languages of Kosovo. Almost 95% of the population speaks Albanian as their native language, followed by South Slavic languages and Turkish. Due to North Kosovo's boycott of the census, Bosnian resulted in being the second-largest language after Albanian. However, Serbian is de facto the second most spoken language in Kosovo. Since 1999, the Albanian language has become the dominant language in the country, although equal status is given to Serbian and special status is given to other minority languages.[182]

The National Assembly adopted the Law on the Use of Languages in 2006 committed Kosovo institutions to ensuring the equal use of Albanian and Serbian as the official languages.[183] Additionally, other languages can also gain recognition at municipal level as official languages if the linguistic community represents at least 5% of the total population of municipality.[183] The Law on the Use of Languages gives Turkish the status of an official language in the municipality of Prizren, irrespective of the size of the Turkish community living there.[183] Although both Albanian and Serbian are official languages, municipal civil servants are only required to speak one of them in a professional setting and, according to Language Commissioner of Kosovo Slaviša Mladenović statement from 2015, no organizations have all of their documents in both languages.[184]

Urbanization

| Largest urban areas of Kosovo KAS Population of Kosovo 2015 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pristina Prizren |

Rank | City | Population | Rank | City | Population |  Ferizaj  Gjakova | |||

| 1 | Pristina | 204,721 | 11 | Suva Reka | 59,681 | |||||

| 2 | Prizren | 186,986 | 12 | Orahovac | 58,908 | |||||

| 3 | Ferizaj | 101,174 | 13 | Mališevo | 57,301 | |||||

| 4 | Peć | 97,890 | 14 | Lipljan | 56,643 | |||||

| 5 | Gjakova | 94,543 | 15 | Skenderaj | 51,746 | |||||

| 6 | Podujevo | 83,425 | 16 | Vitina | 46,742 | |||||

| 7 | Mitrovica | 80,623 | 17 | Deçan | 41,173 | |||||

| 8 | Gjilan | 80,525 | 18 | Istok | 39,604 | |||||

| 9 | Vučitrn | 64,578 | 19 | Klina | 39,208 | |||||

| 10 | Glogovac | 60,175 | 20 | Kosovo Polje | 37,048 | |||||

Religion

Kosovo is a secular state with no official state religion. The Constitution provides for freedom of religion and conscience.[157][158] According to the 2011 Census, 95.6% of the population of Kosovo are Muslims though this seems inflated as 7 to 8% are Christians. These figures do not represent individual sects operating in the country such as the Sufism or Bektashism, which are sometimes classified generally under the category of Islam.[185] 3.69% of the population are Catholic and an equal number or up to 5% Orthodox. The Catholic Albanian communities are mostly concentrated in the cities of Gjakova, Prizren, Klina, and a few villages near Peć and Vitina. The Serb minority is largely Serbian Orthodox.

Christianity has a long-standing tradition in the country, dating back to the Illyrians and Romans. During the Middle Ages, the entire Balkan peninsula had been Christianized by both the Romans and Byzantines. From 1389 until 1912, Kosovo was officially governed by the Ottoman Empire and a high level of Islamization occurred. After the second World War, the country was ruled by secular socialist authorities in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. During that period, the population of Kosovo became increasingly secularized. Today, over 90% of its population are from Muslim backgrounds, most of whom are ethnic Albanians[186] but also including Slavs (who mostly identify themselves as Gorani or Bosniaks) and Turks.

According to the 2014 Freedom of Thought reports by the IHEU, the nation was ranked first in the Southern Europe and ninth in the world as Free and equal for tolerance towards religion and atheism.[187]

Health

In the past, Kosovo's capabilities to develop a modern health care system were limited.[188] Low GDP during 1990 worsened the situation even more. However, the establishment of Faculty of Medicine in the University of Pristina marked a significant development in health care. This was also followed by launching different health clinics which enabled better conditions for professional development.[188]

Nowadays the situation has changed and health care system in Kosovo is organised in three sectors including, primary, secondary and tertiary health care.[189] Primary health care in Pristina is organised in thirteen family medicine centres[190] and fifteen ambulantory care units.[190] Secondary health care is decentralised in seven regional hospitals. Pristina does not have any regional hospital and instead uses University Clinical Center of Kosovo for health care services. University Clinical Center of Kosovo provides its health care services in twelve clinics,[191] where 642 doctors are employed.[192] At a lower level, home services are provided for several vulnerable groups which are not able to reach health care premises.[193] Kosovo health care services are now focused on patient safety, quality control and assisted health.[194]

Education

Education for primary, secondary, and tertiary levels are mostly are predominantly public and supported by the state, run by the Ministry of Education. Education takes place in two main stages: primary and secondary education and higher education.

The primary and secondary education is subdivided into four stages such as the preschool education, the primary and low secondary education, high secondary education and the special education. The preschool education is for children from the age of one to five. The primary and secondary education is obligatory for everyone. It is provided by gymnasiums and vocational schools and also available in languages of recognized minorities in the country, where classes are held in Albanian, Serbian, Bosnian, Turkish and Croatian. The first phase (primary education) includes classes from one to five and the second phase (low secondary education) classes from six to nine. The third phase (high secondary education) consist the general education but also the professional education, that is focused on different fields. It lasts four years. However, pupils offers possibilities of applying for higher or university studies. According to the Ministry of Education, children who are not able to get a general education, are able to get a special education (fifth phase).[195]

Higher education can be received in universities and other higher education institutes. These educational institutions offer studies for Bachelor, Master and PhD degrees. The students may choose full-time or part-time studies.

Economy

The Economy of Kosovo is a transition economy. The nations economy suffered from the combined results of political upheaval, the following Yugoslav wars, the Serbian dismissal of Kosovo employees and international sanctions on Serbia of which it was then part. Since Kosovo's Independence in 2008, the economy has grown every year. Despite declining foreign assistance, growth of GDP averaged over 5% a year. This was despite the Global financial crisis of 2009 and the subsequent Eurozone crisis. Additionally, the inflation rate was low. The most economic development, has taken place in the trade, retail and construction sectors. Kosovo is highly dependent on remittances from the Diaspora, FDI and other capital inflows.[196]

Kosovo's largest trading partners are Albania, Italy, Switzerland, China, Germany and Turkey. The Euro is the official currency of country.[197] The Government of Kosovo have signed a free-trade agreements with Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania and the Republic of Macedonia.[17][198][17][199][17][200][17][201] Kosovo is a Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) member, agreed with UNMIK, and enjoys a free trade within the non-European Union countries.[202]

The secondary sector accounted for 22.60 of GDP and a general workforce of 800.000 employees in 2009. There are several reasons for this stagnation, ranging from consecutive occupations, political turmoil and the War in Kosovo in 1999.[203] The electricity sector is considered as one of the sectors with the greatest potential of development.[204] Kosovo has large reserves of lead, zinc, silver, nickel, cobalt, copper, iron and bauxite.[205] The nation has the 5th largest lignite reserves in the World and the 3rd in Europe.[206] The Directorate for Mines and Minerals and the World Bank estimated, that Kosovo had €13.5 billion worth of minerals.[207]

The primary sector is based on small to medium-sized family-owned dispersed units.[208] 53% of the nation's area is agricultural land and 41% forest and forestry land, whereas 6% for others.[209] The arable land is mostly used for corn, wheat, pastures, meadows and vineyards. It contributes almost to 35% of GDP including the forestry sector. Wine has historically been produced in Kosovo. The wine industry is successful and has been growing after Kosovo War. The main heartland of Kosovo's wine industry is in Orahovac, where millions of litres of wine are produced. The main cultivars include Pinot noir, Merlot, and Chardonnay. Kosovo exports wines to Germany and the United States.[210] During the "glory days" of the wine industry, grapes were grown from the vineyard area of 9,000ha, divided into private and public ownership, and spread mainly throughout the south and west of Kosovo. The four state-owned wine production facilities were not as much "wineries" as they were "wine factories". Only the Rahovec facility that held approximately 36% of the total vineyard area had the capacity of around 50 million litres annually. The major share of the wine production was intended for exports. At its peak in 1989, the exports from the Rahovec facility amounted to 40 million litres and were mainly distributed to the German market.[211]

Infrastructure

Currently, there are two main motorways in Kosovo including the R7 connecting Kosovo with Albania and the R6 connecting Pristina with the Macedonian border at Hani i Elezit. The construction of the new R7.1 Motorway began in 2017.

The R7 Motorway (part of Albania-Kosovo Highway) links Kosovo to Albania's Adriatic coast in Durrës. Once the remaining European route (E80) from Pristina to Merdare section project will be completed, the motorway will link Kosovo through the present European route (E80) highway with the Pan-European corridor X (E75) near Niš in Serbia. The R6 Motorway is currently under construction. Forming part of the E65, it is the second motorway constructed in the region and it links the capital Pristina with the Macedonian border at Elez Han, which is about 20 km (12 mi) from Skopje. Construction of the motorway started in 2014 and it is going to be finished in 2018.

The nation hosts two Airports such as the Gjakova Airport and the only International Airport of Pristina. The Gjakova Airport was built by the Kosovo Force (KFOR) following the Kosovo War, next to an existing airfield used for agricultural purposes, and was used mainly for military and humanitarian flights. The local and national government plans to offer Gjakova Airport for operation under a public-private partnership with the aim of turning it into a civilian and commercial airport.[212] The Pristina International Airport is located southwest of Pristina. It is Kosovo's only international airport and the only port of entry for air travelers to Kosovo.

Tourism

The natural values of Kosovo represent quality tourism resources. The description of Kosovo's potential in tourism is closely related to its geographic position. Its position in the centre of the Balkan Peninsula in south-eastern Europe represents a crossroads which historically dates back to Illyrian and Roman times. With its central position in the Balkans, it serves as a link in the connection between central and south Europe, the Adriatic Sea, and Black Sea. The mountainous south of Kosovo has great potential for winter tourism. Skiing takes place at the winter resort Brezovica in the Šar Mountains. It offers perfect weather and snow conditions for ski seasons from November to May.[213]

The New York Times included Kosovo on the list of 41 Places to go in 2011.[214][215] In the same year, Kosovo saw a jump of about 40 places on the Skyscanner flight search engine which rates global tourism growth.[216][217]

Kosovo is generally rich with mountains, artificial lakes, canyons and rivers and therefore also offers prime possibilities for hunting and fishing.[213] Brezovica also includes three hotels with 680 rooms, two restaurants and nine ski lifts with a transport capacity of 10,000 skiers per hour. With close proximity to Pristina International Airport (60 km) and Skopje Airport (70 km), the resort is a possible destination for international tourists and has the potential to become the most desired winter tourism destination in the Balkans.

Culture

Architecture

The Architecture of Kosovo dates back to the Neolithic Period and includes the Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages, Antiquity and the Medieval period. It has been influenced by the presence of different civilizations and religions as evidenced by the structures which have survived to this day.

Kosovo is home to many Monasteries and Churches from the 13th and 14th century that represents the Serbian Orthodox legacy. Architectural heritage from the Ottoman Period includes mosques and hamams from the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. Other historical architectural structures of interest include kullas from the 18th and 19th centuries as well as a number of bridges, urban centers and fortresses. While some vernacular buildings are not considered important in their own right, taken together they are of considerable interest. During the 1999 conflict in Kosovo, many buildings that represent this heritage were destroyed or damaged.[218][219] In the Dukagjini region, at least 500 kullas were attacked, and most of them destroyed or otherwise damaged.[17]

In 2004, UNESCO recognized the Visoki Dečani monastery as World Heritage Site for its outstanding universal value. Two years later, the site of patrimony was extended as a serial nomination, to include three other religious monuments: Patriarchate of Peć, Our Lady of Ljeviš and Gračanica monastery under the name of Medieval Monuments in Kosovo.[220] It is consisting of four Serbian Orthodox churches and monasteries which represent the fusion of the eastern Orthodox Byzantine and the western Romanesque ecclesiastical architecture to form the Palaiologian Renaissance style. The construction was founded by members of Nemanjić dynasty, the most important dynasty of Serbia in the Middle Ages.

These monuments have come under attack, especially during the 2004 ethnic violence. In 2006, the property was inscribed on the List of World Heritage in Danger due to difficulties in its management and conservation stemming from the region's political instability.[221]

Art

Kosovan art was unknown to the international public for a very long time, because of the regime, many artists were unable to display their art in art galleries, and so were always on the lookout for alternatives, and even resorted to taking matters into their own hands. During the Kosovo War, many studios were burned down and many artworks were destroyed or lost. Until 1990, artists from Kosovo presented their art in many prestigious worldwide renowned centers. They were affirmed and evaluated highly because of their unique approach to the arts considering the circumstances in which they were created, making them distinguished and original.

On February 1979, the Kosova National Art Gallery was founded. It became the highest institution of visual arts in Kosovo. It was named after one of the most prominent artists of Kosovo Muslim Mulliqi. Engjëll Berisha, Masar Caka, Tahir Emra, Abdullah Gërguri, Hysni Krasniqi, Nimon Lokaj, Aziz Nimani, Ramadan Ramadani, Esat Valla and Lendita Zeqiraj are some of few Albanian painters born in Kosovo.

Cuisine

The cuisine in Kosovo is similar to the cuisine of the surrounding places (Albania, Montenegro, Greece), and has been significantly influenced by Turkish cuisine and Albanian cuisine. Common dishes include burek, pies, flija, kebab, suxhuk and other sausages, stuffed peppers, lamb, beans, sarma, burjan, pita and rice.[222] Bread and dairy are important staples in Kosovar Albanian cuisine.

The most widely used dairy products are milk, yogurt, ayran, spreads, cheese and kaymak. Meat (beef, chicken and lamb), beans, rice and peppers are, likewise, major parts of the Kosovo Albanian diet. Vegetables are used seasonally. Usually, cucumbers, tomatoes and cabbage are pickled. Herbs such as salt, black pepper, red pepper and Vegeta are also popular.[223]

Traditional Kosovan desserts are often made with sherbet, which is cooked sugar with either lemon or vanilla flavor. Baklava is one of the most widely used pastries in Kosovo. Another is Kajmaçin, which is composed of baked eggs, mixed with sugar and oil. Sheqer Pare is a pastry similar to baklava, as it is topped with sherbet. Other pastries such as Kaqamak, Tespishte, Rovani, Tulluma and Pallaqinka are also a very popular breakfast foods in Kosovo. They are usually topped with Nutella, cheese, or honey. Shampite or Llokuma is served as a treat for children, and mostly as the first treat to guests on the days of Bajram.[224]

Cinema

"Kosovo is known more for conflict than culture, but at a film festival in the country’s prettiest town, partying and arts mix to great effect." - The Guardian[225]

The film industry of Kosovo dates from the 1970s. In 1969, the parliament of Kosovo established Kosovafilm, a state institution for the production, distribution and showing of films. Its initial director was the actor Abdurrahman Shala, followed by writer and noted poet Azem Shkreli, under whose direction the most successful films were produced. Subsequent directors of Kosovafilm were Xhevar Qorraj, Ekrem Kryeziu and Gani Mehmetaj. After producing seventeen feature films, numerous short films and documentaries, the institution was taken over by the Serbian authorities in 1990 and dissolved. Kosovafilm was reestablished after Yugoslav withdrawal from the region in June 1999 and has since been endeavoring to revive the film industry in Kosovo.

The International Documentary and Short Film Festival is the largest film event in Kosovo. The Festival is organized in August in Prizren which attracts numerous international and regional artists. In this annually organized festival films are screened twice a day in three open air cinemas as well as in two regular cinemas. Except for its films, the festival is also well known for lively nights after the screening. Various events happen within the scope of the festival: workshops, DokuPhoto exhibitions, festival camping, concerts, which altogether turn the city into a charming place to be. In 2010 Dokufest was voted as one of the 25 best international documentary festivals.In 2010 Dokufest was voted as one of the 25 best international documentary festivals.[226]

International actors of Albanian origin from Kosovo include Arta Dobroshi, James Biberi, Faruk Begolli and Bekim Fehmiu. The Prishtina International Film Festival is the largest film festival, held annually in Pristina, in Kosovo that screens prominent international cinema productions in the Balkan region and beyond, and draws attention to the Kosovar film industry.

The movie Shok was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Live Action Short Film at the 88th Academy Awards.[227] The movie was written and directed by Oscar nominated director Jamie Donoughue, based on true events during the Kosovo war. Shok's distributor is Ouat Media, and the social media campaign is led by Team Albanians.

Music

.jpg)

Kosovo-Albanian singer Rona Nishliu represented Albania at the 2012 Eurovision Song Contest in Baku, where she finished 5th. (right)

Although the music in Kosovo is diverse, authentic Albanian and Serbian music still exist. Albanian music is characterised by the use of the Çifteli (authentic Albanian instrument), mandolin, mandola and percussion. Classical music is well known in Kosovo and has been taught at several music schools and universities (at the University of Prishtina Faculty of Arts in Pristina and the University of Priština Faculty of Arts at Mitrovica). In 2014 Kosovo submitted their first film for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, with Three Windows and a Hanging directed by Isa Qosja.[228]

In the past, epic poetry in Kosovo and Northern Albania was sung on a lahuta (one-string fiddle) and then a more tuneful çiftelia was used which has two strings-one for the melody and one for drone. Kosovan music is influenced by Turkish music due to the almost 500-year span of Ottoman rule in Kosovo though Kosovan folklore has preserved its originality and exemplary.[229] Archaeological researches tells about how old is this tradition and how was it developed in parallel way with other traditional music in the Balkan. There were found lots of roots since 5th century BC like paintings in the stones of singers with instruments. (Is famous the portrait of "Pani" who was holding an instrument similar to flute)[230]

The contemporary music artists Rita Ora, Dua Lipa and Era Istrefi, are all of Albanian origin and have achieved international recognition for their music.[231] One widely recognised musician from Prizren is guitarist Petrit Çeku, winner of several international prizes.[232]

Serbian music from Kosovo presents a mixture of traditional music, which is part of the wider Balkan tradition, with its own distinctive sound, and various Western and Turkish influences.[233] Serb songs from Kosovo were an inspiration for 12th song wreath (sr. Руковет) by composer Stevan Mokranjac. Most of Serbian music from Kosovo was dominated by church music, with its own share of sung epic poetry.[233] Serbian national instrument Gusle is also used in Kosovo.[234]