Konstantin Balmont

| Konstantin Balmont | |

|---|---|

|

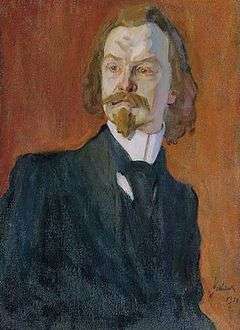

Portrait of Konstantin Balmont by Valentin Serov. 1905. | |

| Born |

Konstantin Dmitrievich Balmont 15 June [O.S. 3 June] 1867 Shuya, Vladimir Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died |

23 September 1942 (aged 75) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Citizenship | Russian Empire / France |

| Education | Moscow University (dropped) |

| Period | 1885–1937 |

| Genre | poetry • memoirs • political essay |

| Literary movement | Russian symbolism |

| Notable works | Burning Buildings (1900) • Let Us Be Like the Sun (1903) |

| Spouse | Larisa Garelina • Yekaterina Andreeva • Elena Tzvetkovskaya |

| Children | Nikolai Bal'mont, Nina (Ninika) Bruni (neé Balmont), Mirra Balmont, Georges Shahovskoy, Svetlana Shales (neé Shahovskoy) |

Konstantin Dmitriyevich Balmont (Russian: Константи́н Дми́триевич Бальмо́нт; IPA: [kənstɐnˈtʲin ˈdmʲitrʲɪjɪvʲɪtɕ bɐlʲˈmont]; 15 June [O.S. 3 June] 1867 – 23 December 1942) was a Russian symbolist poet and translator. He was one of the major figures of the Silver Age of Russian Poetry.

Biography

Konstantin Balmont was born at his family's estate Gumnishchi, Shuya (then Vladimir Governorate, now Ivanovo Oblast), the third of the seven sons of a Russian nobleman, lawyer and senior state official Dmitry Konstantinovich Balmont and Vera Nikolayevna (née Le′bedeva) who came from a military family.[1] The latter knew several foreign languages, was enthusiastic about literature and theater and exerted strong influence on her son.[2][3] Balmont learned to read at the age of five and cited Aleksandr Pushkin, Nikolai Nekrasov, Alexey Koltsov and Ivan Nikitin as his earliest influences.[4] Later he remembered the first ten years of his life spent at Gumnishchi with great affection and referred to the place as 'a tiny kingdom of silent comfort'.[5]

In 1876 the family moved to Shuya where Vera Nikolayevna owned a two-story house.[1] At age ten Konstantin joined the local gymnasium, an institution he later described as "the home of decadence and capitalism, good only at air and water contamination."[6]:9 It was there that he became interested in French and German poetry and started writing himself. His first two poems, though, have been panned by his mother in such a manner that for the next six years he made no attempt at repeating this first poetic venture.[7] At the gymnasium Balmont became involved with a secret circle (formed by students and some teachers) which printed and distributed Narodnaya Volya proclamations.[7] "I was happy and I wanted everybody to be happy. The fact that only a minority, myself included, were entitled to such happiness, seemed outrageous to me," he later wrote.[8] On 30 June 1886 he was expelled from the Shuia gymnasium for his political activities.

Vera Nikolayevna transferred her son to a Vladimir gymnasium, but here the boy had to board with a Greek language teacher who took upon himself a duty of a warden. In the late 1885 Balmont made his publishing debut: three of his poems appeared in a popular Saint Petersburg magazine Zhivopisnoye Obozrenye. This event (according to the biographer Viktor Bannikov) "was noticed by nobody except for his (tor)mentor" who forbade the young man to publish anything further.[7][9]

In 1886 Balmont graduated the much hated gymnasium ("It completely ruined my nervous system," he remembered in 1923)[10] and enrolled in the Moscow University to study law.[11] There he became involved with a group of leftist activists and was arrested for taking part in the students' unrest.[10] He spent three days in prison, was expelled from the University and returned home to Shuya.[12] In 1889 Balmont returned to the University but soon quit again, due to nervous breakdown. He joined the Demidov Law college in Yaroslavl but dropped out in September 1890 deciding he'd had enough of formal education.[3] "I simply couldn't bring myself to study law, what with living so intensely through the passions of my heart," he wrote in 1911.[10][13] In February 1889 he married Larisa Mikhailovna Garelina; unhappy in marriage, on 13 March 1890 Balmont attempted suicide by leaping from a third-storey window, leaving him with a limp and an injured writing hand for the rest of his life[14] A year of recuperation became a turning point for Balmont, who, in his words, experienced 'extraordinary mental agitation' and envisaged his 'poetic mission.'[9][15]

Debut

In 1890 Balmont released a self-financed book called Collection of Poems (Sbornik stikhotvoreny),[16] which included some of the pieces published in 1885.[17] Instrumental in helping the publication was Vladimir Korolenko, by then an established writer who two had received a handwritten notebook (sent to him by Konstantin's classmates) and sent back detailed and favourable critical analysis. He praised the schoolboy's eye for detail, warned against the occasional lapse of concentration and advised to "trust this unconscious part of human soul which accumulates momentary impressions."[18] "Should you learn to concentrate and work methodically, in due time we'll hear of your having developed into something quite extraordinary", were the last words of this remarkable letter.[7] Balmont was greatly impressed with the famous writer's magnanimity and later referred to Korolenko as his 'literary godfather'.[6]:10 The book, though, proved to be a failure.[19] Disgusted with it, Balmont purchased and burnt all of its copies.[2] "My first book, of course, was a total failure. People dear to me have made this fiasco even less bearable with their negativism," he wrote in 1903,[20]:376 meaning apparently Larisa, but also his university friends who considered the book 'reactionary' and scorned its author for 'betraying the ideals of social struggle'. Again, Korolenko came to help. "The poor guy is very shy; a mere attention to his work would make great difference," he wrote to Mikhail Albov, one of the editors of Severny Vestnik, in September 1891.[21]

In 1888–1891 Balmont published several poems he translated from German and French.[4] For a while none of the literary journals showed interest in Balmont's own work.

Some crucial practical help came from the Moscow University professor Nikolai Storozhenko. "Were it not for him. I would have died of hunger," Balmont later remembered.[12] The professor accepted his essay on Percy Bysshe Shelley and in October 1892 introduced him to the authors of Severny Vestnik, including Nikolay Minsky, Dmitry Merezhkovsky and Zinaida Gippius, as well as the publisher Kuzma Soldatyonkov, who commissioned him to translate two fundamental works on the history of the European literature. These books, published in 1894–1895, "were feeding me for three years, making it possible for me to fulfill all my poetic ambitions," Balmont wrote in 1922.[22] All the while he continued to translate Shelley and Edgar Allan Poe. The lawyer and philanthropist Prince Alexander Urusov, an expert in West European literature, financed the publication of two of the Poe's books, translated by Balmont.[19] These translations are still held by Russian literary scholar as exemplary.[6]:11 In 1894 Balmont met Valery Bryusov, who, impressed by the young poet's "personality and his fanatical passion for poetry," soon became his best friend.[23]

1893–1899

In December 1893 Balmont informed Nikolai Minsky in a letter: "I've just written a series of my own verse and I am planning to start the publishing process in January. I anticipate my liberal friends to be outraged for there's not much liberalism in this, while 'corrupting influences' are aplenty."[24] Under the Northern Sky (Под северным небом) came out in 1894 and marked the starting point in his literary career, several critics praising the young author's originality and versatility.[6]:12 The second collection, In Boundlessness (В безбрежности, 1895) saw Balmont starting to experiment with the Russian language's musical and rhythmical structures. Mainstream critics reacted coolly,[6]:12 but the Russian cultural elite of the time hailed the author as gifted innovator.[9] Around this time Balmont met and became close friends with Sergei Poliakov, Knut Hamsun's Russian translator and an influential literary entrepreneur (who in 1899 would launch the Scorpion publishing house).[25] He also became a close friend of Bryusov, who had a formative influence on the development of Balmont's poetic and critical voice. In 1896 Balmont married Ekaterina Alekseyevna Andreeva, and the couple went abroad that year to travel through Western Europe.[6]:12 All the while Balmont was engaged in an intensive self-education: he learned several languages and became an expert in various subjects like the Spanish art and the Chinese culture.[7] In the spring of 1897 Oxford University invited Balmont to read lectures on Russian poetry.[26] "For the first time ever I've been given the opportunity to live my life totally in accord with my intellectual and aesthetic interests. I'll never get enough of this wealth of arts, poetry and philosophy treasures ," he wrote in a letter to critic Akim Volynsky.[27] These European impressions have formed the basis for Balmont's third collection Silence (Тишина, 1898).[7]

1900–1905

After two years of continuous travelling Balmont settled at Sergey Polyakov's Banki estate to concentrate on his next piece of work. In the late 1899 he informed the poet Lyudmila Vilkina in a letter:

I write non-stop. My love of life grows and now I want to live forever. You won't believe how many new poems I've written: more than a hundred! It's madness, it's fantasy and it's something new. The book I'm going to publish will be different. It will raise many eyebrows. My understanding of the state of things has totally changed. It may sound funny, but I'll tell you: now I understand how the world works. For many years [this understanding] will stay with me, hopefully forever.[6]:15[28]

The book in question, Burning Buildings (Горящие здания, 1900), a collection of innovative verse aimed at "inner liberation and self-understanding," in retrospect came to be regarded as an apex of Balmont's legacy.[3] In it Balmont's Nietzschean individualism reached almost religious dimensions, typified by lines like: "O yes, I am the Chosen, I am the Wise, I am the Initiate / The Son of the Sun, I am a poet, the son of reason, I am emperor." In 1901 Balmont sent Leo Tolstoy a copy of it, saying in a letter: "This book is a prolonged scream of a soul caught in the process of being torn apart. One might see this soul as low or ugly. But I won't disclaim not a single page of it as long I keep in me this love for ugliness which is as strong as my love of harmony."[29] Burning Buildings made Balmont the most popular poet in the Russian Symbolist movement. He introduced formal innovations that were widely emulated in Russian verse, including melodic rhythms, abundant rhymes, and the meticulous organization of short lyric poems into narrative poems, cycles, and other compositional units. "For a decade he was a towering presence in Russian poetry. Others either meekly followed or were struggling painfully to free themselves from his overbearing influence," wrote Valery Bryusov later.[30] He was known also for his prolific output, which over time became seen as a shortcoming. "I churn out one page after another, hastily... How unpredictable one's soul is! One more look inside, and you see the new horizons. I feel like I've struck a goldmine. Should I keep on this way, I'll make a book that will never die," he wrote to Ieronim Yasinsky in 1900.

In March 1901 Balmont took part in a student demonstration on the square before Kazan Cathedral which was violently disrupted by the police and Cossack units.[6]:14 Several days later at a literary event in the Russian State Duma he recited his new poem "The Little Sultan" (Malenkii sultan), a diatribe against Tsar Nicholas II, which then circulated widely in hand-written copies.[7] As a result, Balmont was deported from the capital and banned for two years from living in university cities. On 14 March 1902 Balmont departed Russia for Britain and France, lecturing at the Russian College of Social Sciences Paris. While there he met Elena Konstantinovna Tsvetkovskaya, the daughter of a prominent general, who by 1905 became his third (common-law) wife. In 1903 Balmont returned to Russia, his administrative restrictions having been removed by Interior Minister von Plehve. Back in Moscow, he joined Bryusov and Poliakov in the founding of a journal Vesy (The Scales), published by Scorpion.[9]

In 1903 Let Us Be Like the Sun. The Book of Symbols (Будем как Солнце. Книга Символов) came out to great acclaim.[31] Alexander Blok called it "unique in its unfathomable richness."[6]:15 In 1903 Balmont moved to the Baltic Sea shore to work on his next book, Only Love (Только любовь, 1903) which failed to surpass the success of the two previous ones, but still added to the cult of Balmont.[32] "Russia was passionately in love with him. Young men whispered his verses to their loved ones, schoolgirls scribbled them down to fill their notebooks," Teffi remembered.[33] Established poets like Mirra Lokhvitskaya, Valery Bryusov, Andrey Bely, Vyacheslav Ivanov, Maximilian Voloshin and Sergey Gorodetsky treated him (according to biographer Darya Makogonenko) as a "genius… destined to rise high above the world by submerging himself totally into depths of his soul."[6]:5 In 1904 Bal'mont published his collected writings in prose as Mountain Peaks (Gornye vershiny).

In 1904–1905 Scorpion published a two-volume set of Balmont's collected work, followed in 1905 by the collection A Liturgy of Beauty. Elemental Hymns (Литургия красоты. Стихийные гимны) and Fairy's Fairytales (Фейные сказки, both 1905). The first one dealt mostly with his impressions of the Russian-Japanese War,[10] the second was a children's book written for daughter Nina Balmont. Neither collection was received as warmly as their predecessors; in retrospect many contemporaries recognized this as the beginning of Balmont's long decline as a poet. Back from his trip to Mexico and California, Balmont became involved in the 1905 street unrest, reciting poems on barricades and (according to Yekaterina Andreyeva) "carrying a pistol in the pocket wherever he went." Now friends with Maxim Gorky, he contributed both to the latter's New Life (Novaya zhizn) and Paris-based Red Banner (Krasnoye znamya) radical newspapers.[26] On December 31, 1905, he flew to Paris so as to avoid arrest.[7] Balmont's posturing as political immigrant was ridiculed in Russia at the time, but years later researchers found evidence that the Russian secret police considered the poet a 'dangerous political activist' and tried to spy on him abroad. Balmont returned to Russia only in 1913 after an amnesty on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty.[3]

1906–1917

Balmont's next two books collected the poetry written during and in the wake of the First Russian revolution events. Inspired by Walt Whitman, whom he was translating at the time, Balmont gathered his civic verse into the ecollection Poems (Стихотворения, 1906), which was immediately confiscated by the police. Songs of the Avenger (Песни мстителя, 1907), containing direct calls for the assassination of the Tsar, was banned in Russia and came out in Paris. Evil Charms (Злые чары, 1906) was banned for its allegedly anti-religious sentiments. In 1907–1912 Balmont travelled continuously. Snakes' Flowers (Zmeinye tsvety. 1910) and The Land of Osiris (Krai Ozirisa, 1914) collected his travel sketches. Then came the Russian folklore-orientated Firebird. Slav's Svirel (Жар-птица. Свирель славянина, 1907), Birds in the Air (Ptitsy v vozdukhe, 1908), Green Vertograd. Words Like Kisses (Зелёный вертоград. Слова поцелуйные, 1909) and The Glow of Dawns (Zarevo zor', 1912). In Ancient Calls (Зовы древности, 1909) Balmont adapted poems and inscriptions from a variety of ancient sources. Both critics and fellow poets (close friend Bryusov among them) saw these post-1905 books as manifesting a deep creative crisis,[10] of which the poet himself, apparently, remained unaware.[2] Vladimir Markov later argued that Green Vertograd marked the start of a new ascent in Balmont's lyrical poetry, based on the reworking of folkloric material (mostly but not exclusively Russian in origin).[34] A somewhat better reception awaited White Lightnings (Белые зарницы, 1908) and Luminous Sea (Морское свечение, 1910), collecting his essays on Russian and foreign authors.[3]

The outbreak of the World War I found Balmont in France and he had to make a long trip through United Kingdom, Norway and Sweden to return home in May 1915. In 1916 he traveled through the entire Empire, giving readings to large audiences and reached Japan, where he was also warmly received.[6]:18 During the war Balmont published Ash. The Vision of a Tree (Ясень. Видение древа, 1916) and 255 sonnets under the title Sonnets of the Sun, Honey and the Moon (Сонеты Солнца, мёда и Луны, 1917). Both books were received warmly by the public, though the majority of critics found them monotonous and banal.[26] Balmont also composed longer poems, including six garlands of sonnets.[7] He made new friends, including the composers Alexander Skryabin[35] and Sergei Prokofiev, collaborating with the latter on musical works. His 1915 volume Poetry as Magic gave the most coherent and influential statement of his theoretical positions on poetry. White Architect (1914) confirmed Balmont's return as a lyric poet; Markov underscores its more classical qualities of "energy, viritlity, solidity, finish."[34] In 1914 the publication of Balmont's Complete Works in ten volumes commenced.[26]

1917–1942

Balmont welcomed the February Revolution and even entered the competition for a new Russian national anthem, but the failure of the Provisional Government and the October revolution left him bitterly disappointed. He joined the Constitutional Democratic Party and praised Lavr Kornilov in one of his articles.[6]:18 He condemned the dictatorship of proletariat doctrine as destructive and suppressive.[3][4] Still, in his essay Am I a Revolutionary or Not? he argued that a poet should keep away from political parties and keep "his individual trajectory which is more akin to that of a comet rather than a planet."[19]

1918–1920 were the years of great hardship for Balmont who, living in Petrograd (with Elena Tsvetkovskaya and their daughter Mirra)[36] had also to support Andreyeva and their daughter Nina, in Moscow.[12] He struck up a friendship with Marina Tsvetayeva, another poet on the verge of physical collapse.[6]:18 Unwilling to collaborate with the Bolsheviks (whose "hands were smeared with blood," as he declared openly at one of the literary meetings) occasionally he had to. In 1920 Anatoly Lunacharsky (urged by Jurgis Baltrushaitis, then the head of Lithuanian diplomatic mission in Moscow) granted Balmont the permission to leave the country. Boris Zaitsev later opined that what Baltrushaitis did was actually save Balmont's life. According to the Sergey Litovtsev (a Russian critic who lived in immigration) at one of the Cheka secret meetings the fate of Balmont was discussed, "...it's just that those demanding him being put to a firing squad happened to be in the minority at the time."[37] On May 25, 1920, Balmont and his family left Russia for good.[6]:19 As soon as Balmont reached Reval, rumors began to circulate that he had begun to make anti-Soviet public statements, leading to the cancellation of other writers' journeys out of Soviet Russia. Balmont denied these rumors, and there is no evidence to support them, but by 1921 Balmont was regularly publishing inflammatory articles against the Soviet government in the émigré press.[38]

In Paris Balmont found himself unpopular. Radical Russian emigres took his safe and easy departure as a sign of him being a Communist sympathizer.[37] Lunacharsky with his apologetic article ensuring the public at home that Balmont's stance wasn't in any way anti-Bolshevik, played up to these suspicions. On the other hand, the Bolshevik press accused of 'treacherousness' the poet, who "having been sent to the West on a mission to collect common people's revolutionary poetry abused the trust of the Soviet government." Condemning repressions in Russia, Balmont was critical of his new environment too, speaking of many things that horrified him in the West.[37] What troubled him most though, was his longing for Russia. "Not a single other Russian poet in exile suffered so painfully from having been severed from his roots," the memoirist Yuri Terapiano later argued.[39] For Balmont his European experience was the "life among aliens." "Emptiness, emptiness everywhere. Not a trace of spirituality here in Europe," he complained in a December 1921 letter to Andreyeva.[26]

In 1921 Balmont moved out of Paris into the province where he and his family rented houses in Brittany, Vendee, Bordeaux and Gironde.[4] In the late 1920s his criticism of both the Soviet Russia and what he saw as the leftist Western literary elite’s indifference to the plight of the Russian people, became more pronounced. Great Britain's acknowledgement of the legitimacy of (in Balmont's words) "the international gang of bandits who seized power in Moscow and Saint Petersburg" rendered "a fatal blow to the last remnants of honesty in the post-War Europe."[40] Still, unlike his conservative friend Ivan Shmelyov, Balmont was a liberal: he detested fascism and right-wing nationalist ideas. All the while, he shied the Russian Socialists (like Alexander Kerensky and Ilya Fondaminsky) and expressed horror at what he saw as France's general 'enchantment' with Socialism. His views in many ways were similar to those of Ivan Bunin; the two disliked each other personally, but spoke in one voice on many occasions.[41]

In emigration Balmont published several books of poetry, including A Gift to Earth (Дар Земле), Lightened Hour (Светлый час, both 1921), The Haze (Марево, 1922), From Me to Her. Poems of Russia (Моё — ей. Стихи о России, 1923), Beyond Stretched Horizons (В раздвинутой дали, 1929), Northern Lights (Северное сияние, 1933), Blue Horseshoe (Голубая подкова) and Serving the Light (Светослужение, both 1937). He released autobiographies and memoirs: Under the New Sickle (Под новым серпом), The Airy Path (Воздушный путь, both 1923) and Where Is My Home? (Где мой дом?, Prague, 1924). Balmont's poetry in emigration was criticized by Vladimir Nabokov who called his verse "jarring" and "its new melodies false."[42] Nina Berberova argued that Balmont exhausted his muse while in Russia and none of his later work was worthy of attention. Modern Russian critics assess Balmont's last books more favourably, seeing them as more accessible and insightful, even if certainly less flamboyant than his best known work. The poet and biographer Nikolai Bannikov called poems "Pines in Dunes" (Дюнные сосны) and "Russian Language" (Русский язык) "little masterpieces". From the mid-1920s Balmont turned his gaze to Eastern Europe, traveling to centers of the Russian emigration in Lithuania, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria, translating poetry from their languages, and adapting their folklore in his own original work.[7]

In the early 1930s, as the financial support from the Czech and Yugoslav governments stopped, Balmont, who had to support three women, fell into poverty. Ivan Shmelyov provided moral support, professor Vladimir Zeeler some financial help. By 1932 triggered at least to some extent by his alcohol abuse in the 1920s.[43] In April 1936 the group of Russian writers and musicians abroad celebrated the 50th anniversary of Balmont's literary career by staging a charity event; among organizers and contributors were Shmelyov, Bunin, Zaitsev, Sergei Rachmaninoff and Mark Aldanov.[41]

Konstantin Balmont died on December 23, 1942 in a refuge for Russian emigres, the Russian House, due to complications of pneumonia. He is interred in Noisy-le-Grand's Catholic cemetery, four words engraved on a grey tomb: "Constantin Balmont, poete russe". Among the several people who came to the funeral, were Zaitsev, daughter Mirra and Jurgis Baltrushaitis' widow.[25][44]

Personality

Konstantin Balmont has been characterized variously as theatrical, pretentious, erratic and egotistical.[7] Boris Zaitsev, ridiculing good-humouredly his best friend's vain eccentricities, remembered episodes when Balmont "could be altogether different person: very sad and very simple."[25] Andrey Bely spoke of Balmont as of a lonely and vulnerable man, totally out of touch with the real world. Inconsistency marred his creativity too: "He failed to connect and harmonize those riches he's been given by nature, aimlessly spending his spiritual treasures," Bely argued.[45]

"Balmont was a poseur and the reasons for this were obvious. Ever crowded by worshippers, he was trying to bear himself in a manner he saw as befitting a great poet... It was laughter that gave him away… Just like a child, he was always moved by a momentary impulse," wrote Teffi.[33] "He lives his everyday life as a poet, trying to discover each moment's full richness. That is why one shouldn't judge him by common criteria," Valery Bryusov argued.[46]

Pyotr Pertsov who knew Balmont from teenage years, characterized him as "very nice, friendly and considerate young man." Marina Tsvetayeva insisted that he was "a kind of man who'd give a needy one his last piece of bread, his last log of wood." Mark Talov, a Soviet translator who in the 1920s found himself penniless in Paris, remembered how often, after having left Balmont's house he would find money in a pocket; the poet (who was very poor himself) preferred the anonymous way of help so as not to confuse a visitor.[7]

Bohemian habits notwithstanding, Balmont was a hard worker, proficient and prolific. Eccentric to many, he seemed rational and logical to some. The publisher Sergey Sabashnikov remembered Balmont as "accurate, punctual, pedantic and never slovenly… Such accuracy made Balmont a very welcome client," he added.[15]

Origins

In his 1903 short autobiography Balmont wrote:

According to our family legend, my ancestors were sailors, either Scottish or Scandinavian, who came to Russia and settled there. My father's father was a Navy officer and a hero of Turkish War praised by Tsar Nicholas the First for bravery. My mother's ancestors were Tatars, the first in the line being Prince Bely Lebed (White Swan) of the Golden Horde. That was where two of her distinctive qualities, unruliness and tempestuousness which I inherited, have come from.[20]:375

According to Ekaterina Andreeva's Memoirs,[47] Balmont's paternal grand-grandfather Ivan Andreyevich Balamut (Баламут, the Ukrainian surname, translated literally as "trouble-maker") was a landowner in Kherson, Southern Ukraine, who served as a cavalry sergeant in Catherine the Great's Imperial Guard regiment (Andreyeva insisted she had seen the proof of it in an original parchment-written document kept in the family archives).[26][48]

Dmitry Konstantinovich, Vera Nikolayevna and all of their relatives pronounced the surname with the first syllable stressed. The poet changed its pronunciation to Balmont, citing "a certain woman's whimsy" as the reason for this.[12]

Private life

In 1889, ignoring his mother's warnings, Balmont married Larisa Mikhaylovna Garelina, a daughter of Shuya-based factory-owner, described as a neurasthenic who "gave [the poet] the love of a truly demonic nature".[6]:10 This led first to Balmont's ties with his family being severed,[12][49] then his March 13, 1890, suicide attempt.[7] The couple's first son died in infancy; the second, Nikolai, suffered from mental illness.[12] Later some critics warned against demonizing Larisa Garelina, pointing to the fact that years later she married the well-known Russian journalist and literature historian Nikolai Engelgardt and enjoyed perfectly normal family life with him. Their daughter Anna Engelgardt became the second wife of poet Nikolai Gumilyov.[12]

On 27 September 1896 Balmont married Yekaterina Alekseyevna Andreyeva (1867–1952), a well-educated woman who came from the rich merchants' family, related to the well-known Moscow publishers' clan of Sabashnikovs.[12] Andreyeva and Balmont had much in common; they formed a tandem of translators and worked together on the works of Gerhart Hauptmann and Oscar Wilde.[7] Andreyeva, a strong-minded woman, was a leading force in the family, and in her 'strong, healthy and loving hands' (according Boris Zaitsev, who knew them well) Balmont led a 'disciplined, working man's life.'[25] In 1901 their daughter Nina Balmont (Bruni in marriage, died in Moscow in 1989) was born.[6]:284

In the early 1900s, while in Paris, Balmont met Yelena Konstantinovna Tsvetkovskaya (1880–1943), general K.G. Tzvetkovsky's daughter, a student of mathematics at the University of Paris and the poet's ardent fan. Balmont, as some of his letters suggested, wasn't in love with her, but soon found himself in many ways dependent upon the girl who proved to be a loyal, devoted friend. Balmont's family life got seriously complicated in 1907 when Tsvetkovskaya gave birth to a daughter Mirra, named so by her father in the memory of the poet Mirra Lokhvitskaya, who died in 1905 and with whom he had passionate platonic relations.[6]:19 Torn apart between the two families, in 1909 Balmont attempted suicide for the second time (jumping out a window) and again survived. Up until 1917 he lived in Saint Petersburg with Tsvetkovskaya and Mirra, occasionally visiting Yekaterina and Nina in Moscow.[6]:19 While in France Balmont continued to correspond with Andreyeva up until 1934.[48]

Balmont and Tsvetkovskaya, according to Teffi, communicated in a bizarrely pretentious manner. "She was always calling him 'a poet', never – 'my husband'. A simple phrase like 'My husband asks for a drink' in their special argot would turn into something like: 'A poet is willing to appease his thirst'." [33] Unlike Andreyeva, Yelena Tsvetkovskaya was helpless in domestic life and had no influence over Balmont whatsoever.[33]

From 1919 Balmont was romantically linked with Dagmar Shakhovskaya (née von Lilienfeld, 1893–1967), who followed Balmont to France in 1921. They lived apart except for brief periods, although Dagmar bore Balmont two children: Georges (1922–1943) and Svetlana (b. 1925).[50] Balmont sent her letters or postcards almost daily; in all, 858 of them survived, mostly from 1920-1924.[51] It was Elena Tsvetkovskaya, though, who remained with Balmont until his dying day. She died in 1943, surviving her husband by a year. Mirra Balmont (in her first marriage Boychenko, in the second Ayutina) was a published poet, who used the pseudonym Aglaya Gamayun. She died in Paris in 1970.[41]

In music

Among the Russian composers who have set Balmont's poetry to music were Mikhail Gnessin, Nikolai Myaskovsky, Nikolai Obukhov, Sergei Prokofiev, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Maximilian Steinberg, Igor Stravinsky, and Sergei Taneyev. His free Russian translation of Edgar Allan Poe's The Bells formed the basis for Rachmaninoff's choral symphony of the same name, Op. 35.

Selected works

Poetry collections

- Collection of Poems (Сборник стихотворений, 1890)

- Under the Northern Sky (Под северным небом, 1894)

- In Boundlessness (В безбрежности, 1895)

- Silence (Тишина. Лирические поэмы, 1898)

- Burning Buildings. The Lyric of the Modern Soul (Горящие здания. Лирика современной души, 1900)

- Let Us Be Like the Sun. The Book of Symbols (Будем как солнце. Книга символов, 1903)

- Only Love (Только любовь. Семицветник, 1903)

- Liturgy of Beauty (Литургия красоты. Стихийные гимны, 1905)

- Fairy's Fairytales (Фейные сказки (детские песенки), 1905)

- Vile Charms (Злые чары, 1906)

- Poems (Стихотворения, 1906)

- Firebird. Slavic Svirel (Жар-птица. Свирель славянина, 1907)

- Songs of the Avenger (Песни мстителя, 1907)

- Three Blossoms. Theatre of Youth and Beauty (Три расцвета. Театр юности и красоты, 1907)

- Runaround of Times (Хоровод времён. Всегласность, 1909)

- Birds in the Air (Птицы в воздухе. Строки напевные, 1908)

- Green Vertograd (Зелёный вертоград. Слова поцелуйные, 1909)

- White Architect. Mystery of Four Lanterns (Белый Зодчий. Таинство четырёх светильников, 1914)

- Ash. Visions of a Tree (Ясень. Видение древа, 1916)

- Sonnets of Sun, Honey and Moon (Сонеты Солнца, Мёда и Луны, 1917; published in 1921 in Berlin)

References

- 1 2 Savinova, R.F.. "The Balmonts". The Vladimir Region (Vladimirsky krai) site. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- 1 2 3 "Balmont, Konstantin Dmitrievich". silverage.ru. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Stakhova, M.. "Konstantin Balmont. Lives of The Silver Age Poets". www.litera.ru. Archived from the original on 2011-08-18. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- 1 2 3 4 Polonsky, Vadim. "K.D. Balmont in the Krugosvet (Around the World) encyclopedia". www.krugosvet.ru. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- ↑ Balmont, K.D. At Sunrise. Autobiography. — From K.D.Balmont's Autobiographical prose. Мoscow, 2001, P. 570.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Makogonenko, Darya. Life and Fate (Zhizn i sudba). // Balmont, К. The Selected Works. Poems, translations, essays. Compiled by Darya Makogonenko. Moscow. Pravda Publishers, 1990. ISBN 5-253-00115-8

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Bannikov, Nikolai (1989). "Balmont's Life and Poetry (Zhizn i poeziya Balmonta)". Detskaya Literatura. Balmont, K.D. The Sun's Yarn: Poems, sketches. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- ↑ Balmont, K.D. A Revolutionary: Am I, or Am I Not? / Революционер я или нет?, p. 452.

- 1 2 3 4 Brockhaus and Efron (1911). "Konstantin Dmitrievich Balmont biography". Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Azadovsky, K.M. (1990). "K.D.Balmont. Biography". Russian writers. Biobibliographical dictionary. Vol. 1. Edited by P.A.Nikolayev. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- ↑ "Moscow University poetry". www.poesis.ru. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Aleksandrova, Tatyana Lvovna. "Konstantin Balmont". old.portal-slovo.ru (The Word site). Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- ↑ The Morning of Russia (Utro Rossii). 1911. — December 23.

- ↑ Balmont, K. "Vozdushnyi put',"Russkaya Mysl, No. 11, 1908).

- 1 2 Prashkevich, Gennady. "Russia's Famous Poets. Konstantin Balmont". lib.ololo.cc. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ↑ "Balmont Konstantin Dmitrievich". The Yaroslavl University site. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- ↑ "Balmont Konstantin Dmitrievich". www.russianculture.ru. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- ↑ Balmont, K.D. At The Dawn (Na zare). Autobiographical prose. P. 572.

- 1 2 3 "Balmont Konstantin Dmitrievich". Russian writers of the XX century. Biographical dictionary. Vol.2. Prosveshchenye Publishers. 1998. P.131. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- 1 2 К. Balmont. Autobiographical letter, 17/V/1903 // S.A.Vengerov. Critical and biographical dictionary of Russian writers and scientists. Vol. 6. St.P., 1904

- ↑ Korolenko, V.G. — Selected letters. Vol. 3. Мoscow, 1936. p. 68.

- ↑ Seeing Eyes (Vidyaschyie glaza). Fragments from K.D.Balmont's memoirs. Latest News newspaper, Revel, March 17, 1922.

- ↑ Bryusov, Valery. Autobiography. Russian literature of the ХХ century. Ed. S.A. Vengerov. Vol. 1, Moscow, 1914. P. 111

- ↑ Balmont, K.D. Poems. Leningrad, 1969. P. 23.

- 1 2 3 4 Zaitsev, Boris. "Remembering the Silver Age (Vospominanyia o serebryanom veke)". az.lib.ru. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ozerov, Lev. "Konstantin Balmont and his poetry (Konstantin Balmont i yevo poeziya)". www.litera.ru. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ↑ Volynsky, Akim. Severny Vestnik. 1898, Nos. 8–9

- ↑ Balmont, K.D.. Poems. Leningrad, 1969, p. 50

- ↑ Literaturnoye Nasledstvo. Vol. 69, Book. I. Pp. 135—136

- ↑ Nagorsky, A.V.. "The Greats. Konstantin Balmont". infa.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

- ↑ Bogomolov, N. A.. "To the History of Balmont's Best Book.". НЛО, 2005 N75. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ↑ V.Y.Bryusov's letters to P.P.Pertsov. Мoscow, 1927, p. 78

- 1 2 3 4 Teffi, N.A. (1955). "Balmont. Remembering the Silver Age". Мoscow. Respublika Publishers, 1993. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- 1 2 Vladimir Markov, "Bal'mont: A Reappraisal," Slavic Review 28 (1969)

- ↑ Balmont, K. Zvukovoi zazyv. The Sound Call. Balmont's memoirs on Skryabin

- ↑ "Konstantin Balmont. Letters to Fyodor Shuravin (1937)". www.russianresources.lt. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- 1 2 3 S. Polyakov (Litovtsev). "Of Balmont the Poet". Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ↑ Robert Bird, E. V. Ivanova. “Byl li vinoven Bal’mont?” [Was Bal’mont Guilty?], Russkaia literatura (St. Petersburg). No. 3 (2004) 55-85

- ↑ Terapiano, Yuri (1994). "K.D.Balmont". Distant Shores. Portraits of Writers in Emigration. Compiled and edited by V.Kreid. Moscow. Respublika Publishers. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ↑ Balmont, К. The Angles. The Word of the World (Vsemirnoye slovo), Saint Petersburg, 2001. No. 14. P.8.

- 1 2 3 Azadovsky, K.M., Bongard-Levine, G.M. (2002). "The Meeting. Konstantin Balmont and Ivan Shmelyov". Our Inheritance (Nashe naslediye), No.61. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- ↑ Nabokov, V.V. Iv. Bunin. Selected Poems. Sovremennye zapiski Publishers. Paris, 1929. P. 754.

- ↑ "K.D.Balmont’s letters to V.V.Obolyaninov". dlib.eastview.com. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- ↑ Terapiano, Y. Meetings. New York. Chekhov Publishing House, 1953. P. 21.

- ↑ Bely, Andrey (1910). "Green Meadow (Lug zelyony)". Мoscow, Altsiona Publishers. P. 202. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- ↑ Pyotr Pertsov, Literary memoirs (Literatutnyie vospominaniya). Moscow-Leningrad, 1993, p. 260

- ↑ Andreeva-Balmont, E.A. Vospominaniya. 1997

- 1 2 Simonova, Е., Bozhe, V. "I am For Everyone and for Nobody...". Vechernii Cheliabinsk (newspaper). Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- ↑ Balmont, K.D. Autobiographical prose. Volga magazine. P. 541.

- ↑ "K.D.Balmont' letters to Dagmar Shakhovskaya". www.litera.ru. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- ↑ Konstantin Balmont. My vstretimsia v solnechnom luche… Pisma k Dagmar Shakhovskoi (1919-1924) [Letters to Dagmar]. Eds. Robert Bird and Farida Tcherkassova. Moscow: Russkii put’, 2014

External links

- Bibliowiki has original media or text related to this article: Konstantin Balmont (in the public domain in Canada)

- Collection of Poems by Konstantin Balmont (English Translations)

- Works by or about Konstantin Balmont at Internet Archive

- Four poems in English c. 1900

- Konstantin Balmont poetry at Stihipoeta (in Russian)