Koh-i-Noor

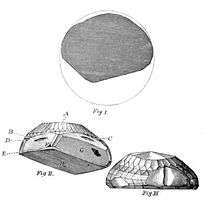

A glass replica of the diamond before it was re-cut in 1852 on display at the Reich der Kristalle museum in Munich, Germany | |

| Weight | 105.602 carats (21.1204 g) |

|---|---|

| Colour | Finest White |

| Mine of origin | Kollur Mine, Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh, India[1] |

| Discovered | 13th century |

| Cut by |

Hortenso Borgia (17th century) Levie Benjamin Voorzanger (1852) |

| Original owner | Kakatiya dynasty |

| Owner | Queen Elizabeth II in right of the Crown.[2] |

The Koh-i-Noor (Persian for Mountain of Light; also spelled Kohinoor and Koh-i-nur) is a large, colourless diamond that was found near Guntur in Andhra Pradesh, India, possibly in the 13th century. According to legend, it first weighed 793 carats (158.6 g) uncut, although the earliest well-attested weight is 186 carats (37.2 g); it was first owned by the Kakatiya dynasty. The stone changed hands several times between various factions in Asia over the next few hundred years, ending up in the possession of Queen Victoria after the British conquest of the Punjab in 1849.

In 1852, Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, was unhappy with its dull and irregular appearance, and he ordered it cut down from 186 carats (37.2 g) by Coster Diamonds. It emerged 42 percent lighter as a dazzling oval-cut brilliant weighing 105.6 carats (21.12 g) and measuring 3.6 cm x 3.2 cm x 1.3 cm.[3] By modern standards, the cut is far from perfect, in that the culet is unusually broad, giving the impression of a black hole when the stone is viewed head-on; it is nevertheless regarded by gemmologists as being full of life.[4] As the diamond's history involves a great deal of fighting between men, the Koh-i-Noor acquired a reputation within the British royal family for bringing bad luck to any man who wears it. Since arriving in the country, it has only ever been worn by female members of the family.[5]

Today, the diamond is set in the front of the Queen Mother's Crown, part of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, and is seen by millions of visitors to the Tower of London each year. The governments of India, Pakistan, Iran and Afghanistan have all claimed ownership of the Koh-i-Noor and demanded its return at various times in recent decades. The British government insists the gem was obtained legally under the terms of the Treaty of Lahore.

Origin and early history

It is widely believed to have come from the Kollur Mine in the Guntur District of present-day Andhra Pradesh India, during the reign of the Hindu Kakatiya dynasty in the 13th century in the Bhadrakali Temple. It is however impossible to know where it was found. In the early 14th century, Alauddin Khalji, second ruler of the Turkic Khalji dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate, and his army began looting the kingdoms of southern India.[6][7] Malik Kafur, Khilji's general, made a successful raid on Warangal in 1310,[8] when he possibly acquired the diamond.[9][10]

It remained in the Khilji dynasty and later passed to the succeeding dynasties of the Delhi Sultanate, until it came into the possession of Babur, a Turco-Mongol warlord, who invaded India and established the Mughal Empire in 1526. He called the stone the "Diamond of Babur" at the time, although it had been called by other names before it came into his possession. Both Babur and his son and successor, Humayun, mentioned the origins of this diamond in their memoirs, thought by many historians to be the earliest reliable reference to the Koh-i-Noor.[11]

Shah Jahan, the fifth Mughal emperor, had the stone placed into his ornate Peacock Throne. In 1658, his son and successor, Aurangazeb, confined the ailing emperor at nearby Agra Fort. While in the possession of Aurangazeb, it was allegedly cut by Hortenso Borgia, a Venetian lapidary so clumsily that he reduced the weight of the stone from 793 carats (158.6 g) to 186 carats (37.2 g).[12] For this carelessness, Borgia was reprimanded and fined 10,000 rupees.[13] According to recent research the story of Borgia cutting the diamond is not correct, and most probably mixed up with the Orlov, part of Catherine the Great's imperial Russian sceptre in the Kremlin.[14]

Acquisition by Nader Shah

Following the 1739 invasion of Delhi by Nader Shah, the Afsharid Shah of Persia, the treasury of the Mughal Empire was looted by his army in an organised and thorough acquisition of the Mughal nobility's wealth.[15] Along with a host of valuable items, including the Daria-i-Noor, as well as the Peacock Throne, the Shah also carried away the Koh-i-Noor. He allegedly exclaimed Koh-i-Noor! (meaning "mountain of light") when he finally managed to obtain the famous stone, and that is how the stone got its name.[16]

The first valuation of the Koh-i-Noor is given in the legend that one of Nader Shah's consorts apparently said, "If a strong man were to throw four stones, one north, one south, one east, one west, and a fifth stone up into the air, and if the space between them were to be filled with gold, all would not equal the value of the Koh-i-Noor".[17]

It is estimated that the total worth of the treasures plundered came to 700 million rupees. This was roughly equivalent to £87.5 million sterling at the time,[18] or approximately £12.6 billion in 2015's money.[19] The riches gained by the Afsharid Empire from the Indian campaign were so monumental that Nader Shah made a proclamation alleviating all subjects of the Empire from taxes for a total of three years.[20]

After the assassination of Nader Shah in 1747 and the collapse of his empire, the stone came into the hands of one of his generals, Ahmad Shah Durrani, who later became the Emir of Afghanistan. One of Ahmed's descendants, Shah Shujah Durrani, wore a bracelet containing the Koh-i-Noor on the occasion of Mountstuart Elphinstone's visit to Peshawar in 1808.[21]

A year later, Shujah formed an alliance with the United Kingdom to help defend against a possible invasion of Afghanistan by Russia.[22] He was quickly overthrown by his predecessor, Mahmud Shah, but managed to flee with the diamond. He went to Lahore, where the founder of the Sikh Empire, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, in return for his hospitality, insisted upon the gem being given to him, and he took possession of it in 1813.[15]

Acquisition by the British

Its new owner, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, willed the diamond to the Hindu temple of Jagannath in Puri, in modern-day Odisha, India.[23] However, after his death in 1839, British administrators did not execute his will.[24] On 29 March 1849, following the conclusion of the Second Anglo-Sikh War, the Kingdom of Punjab was formally annexed to British India, and the Last Treaty of Lahore was signed, officially ceding the Koh-i-Noor to Queen Victoria and the Maharaja's other assets to the company.

Article III of the treaty read:

The gem called the Koh-i-Noor, which was taken from Shah Sooja-ool-moolk by Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, shall be surrendered by the Maharajah of Lahore to the Queen of England.[25]

The Governor-General in charge of the ratification of this treaty was the Marquess of Dalhousie. The manner of his aiding in the transfer of the diamond was criticized even by some of his contemporaries in Britain. Although some thought it should have been presented as a gift to Queen Victoria by the East India Company, it is clear that Dalhousie strongly believed the stone was a spoil of war, and treated it accordingly, ensuring that it was officially surrendered to her by Maharaja Duleep Singh, the youngest son of Ranjit Singh.

Writing to his friend Sir George Cooper in August 1849, he stated:

The Court [of the East India Company] you say, are ruffled up by my having caused the Maharajah to cede to the Queen the Koh-i-noor; while the Daily News and my Lord Ellenborough (Governor-General of India, 1841–44) are indignant because I did not confiscate everything to Her Majesty. The motive was simply this: that it was more for the honour of the Queen that the Koh-i-noor should be surrendered directly from the hand of the conquered prince into the hands of the sovereign who was his conqueror, than it should be presented to her as a gift—which is always a favour—by any joint-stock company among her subjects.[26]

The presentation of the Koh-i-Noor and the Timur ruby by the East India Company to the queen was the latest in a long history of transfers of the stones as coveted spoils of war.[27] Duleep Singh had been placed in the guardianship of Dr John Login (later Sir John Spencer Login), a surgeon in the British Army serving in the Presidency of Bengal, in India. Dr Login and his wife Lena both would later accompany Duleep Singh on his journey to England in 1854.

In due course, the Governor-General received the Koh-i-Noor from Dr Login, who had been appointed Governor of the Citadel, with the Royal Treasury, which Dr Login valued at almost £1,000,000 (£93.6 million in 2015's money),[19] excluding the Koh-i-Noor, on 6 April 1848, under a receipt dated 7 December 1849, in the presence of the members of the Board of Administration for the affairs of the Punjab: Sir Henry Lawrence (President), C. G. Mansel, John Lawrence and Sir Henry Elliot (Secretary to the Government of India).

Legend in the Lawrence family has it that before the voyage, John Lawrence left the jewel in his waistcoat pocket when it was sent to be laundered, and was most grateful when it was returned promptly by the valet who found it.[28]

On 1 February 1850, the jewel was sealed in a small iron safe inside a red dispatch box, both sealed with red tape and a wax seal and kept in a chest at Bombay Treasury awaiting a steamer ship from China. It was then sent to England for presentation to Queen Victoria in the care of Captain J. Ramsay and Brevet Lt. Col F. Mackeson under tight security arrangements, one of which was the placement of the dispatch box in a larger iron safe. They departed from Bombay on 6 April on board HMS Medea, captained by Captain Lockyer.

The ship had a difficult voyage: an outbreak of cholera on board when the ship was in Mauritius had the locals demanding its departure, and they asked their governor to open fire on the vessel and destroy it if there was no response. Shortly afterwards, the vessel was hit by a severe gale that blew for some 12 hours.

On arrival in Britain on 29 June, the passengers and mail were unloaded in Plymouth, but the Koh-i-Noor stayed on board until the ship reached Spithead, near Portsmouth, on 1 July. The next morning, Ramsay and Mackeson, in the company of Mr Onslow, the private secretary to the Chairman of the Court of Directors of the British East India Company, proceeded by train to East India House in the City of London and passed the diamond into the care of the chairman and deputy chairman of the East India Company. The Koh-i-Noor was formally presented to Queen Victoria on 3 July at Buckingham Palace by the deputy chairman of the East India Company.[27] The date was chosen to coincide with the company's 250th anniversary.[29]

The Great Exhibition

Members of the public were given a chance to see the Koh-i-Noor when The Great Exhibition was staged at Hyde Park, London, in 1851. It was displayed in the Works in Precious Metals, Jewellery, etc. part of the South Central Gallery.[30] The Times reported:

The Koh-i-Noor is at present decidedly the lion of the Exhibition. A mysterious interest appears to be attached to it, and now that so many precautions have been resorted to, and so much difficulty attends its inspection, the crowd is enormously enhanced, and the policemen at either end of the covered entrance have much trouble in restraining the struggling and impatient multitude. For some hours yesterday, there were never less than a couple of hundred persons waiting their turn of admission, and yet, after all, the diamond does not satisfy. Either from the imperfect cutting or the difficulty of placing the lights advantageously, or the immovability of the stone itself, which should be made to revolve on its axis, few catch any of the brilliant rays it reflects when viewed at a particular angle.[31]

A French writer gave a vivid description of the exhibit:

On Friday and Saturday it puts on its best dress; it is arrayed in a tent of red cloth, and the interior is supplied with a dozen little jets of gas, which throw their light on the god of the temple. Unhappily, the Koh-i-Noor does not sparkle even then. Thus the most curious thing is not the divinity, but the worshippers. One places oneself in the file to go in at one side of the niche, looks at the golden calf, and goes out the other side. If the organs should chance to play at the same moment, the illusion is complete. The Koh-i-Noor is well secured; it is placed on a machine which causes it, on the slightest touch, to enter an iron box. It is thus put to bed every evening, and does not get up till towards noon. The procession of the faithful then commences, and only finishes at seven o'clock.[32]

After these complaints, the diamond was put in a new shaded case to let the sunlight catch it better.

1852 re-cutting

Disappointment in the appearance of the stone was not uncommon. After consulting various mineralogists, including Sir David Brewster, it was decided by Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, with the consent of the government, to polish the Koh-i-Noor. One of the largest and most famous Dutch diamond merchants, Mozes Coster, was employed for the task. He sent to London one of his most experienced artisans, Levie Benjamin Voorzanger, and his assistants.[15]

On 17 July 1852, the cutting began at the factory of Garrard & Co. in Haymarket, using a steam-powered mill built specially for the job by Maudslay, Sons and Field.[33] Under the supervision of Prince Albert and the Duke of Wellington, and the technical direction of the queen's mineralogist, James Tennant, the cutting took 38 days. Albert had spent a total of £8,000 on the operation, which reduced the weight of the diamond by around 42 percent, from 186 carats (37.2 g) to its current 105.6 carats (21.12 g).[34]

The great loss of weight is to some extent accounted for by the fact that Voorzanger discovered several flaws, one especially big, that he found it necessary to cut away.[15] Although Prince Albert was dissatisfied with such a huge reduction, most experts agreed that Voorzanger had made the right decision and carried out his job with impeccable skill.[34] When Queen Victoria showed the re-cut diamond to the young Maharaja Duleep Singh, the Koh-i-Noor's last non-British owner, he was apparently unable to speak for several minutes afterwards.[4]

The much lighter but more dazzling stone was mounted in a brooch worn by the queen. At this time, it belonged to her personally, and was not yet part of the Crown Jewels.[15] Although Victoria wore it often, she became uneasy about the way in which the diamond had been acquired. In a letter to her eldest daughter, Victoria, Princess Royal, she wrote in the 1870s: "No one feels more strongly than I do about India or how much I opposed our taking those countries and I think no more will be taken, for it is very wrong and no advantage to us. You know also how I dislike wearing the Koh-i-Noor".[35]

The Crown Jewels

After Queen Victoria's death, the Koh-i-Noor was set in the Crown of Queen Alexandra, the wife of Edward VII, that was used to crown her at their coronation in 1902. The diamond was transferred to Queen Mary's Crown in 1911,[36] and finally to The Queen Mother's Crown in 1937.[37] When The Queen Mother died in 2002, it was placed on top of her coffin for the lying-in-state and funeral.[38]

All these crowns are on display in the Jewel House at the Tower of London with crystal replicas of the diamond set in the older crowns.[39] The original bracelet given to Queen Victoria can also be seen there. A glass model of the Koh-i-Noor shows visitors how it looked when it was brought to the United Kingdom. Replicas of the diamond in this and its re-cut forms can also be seen in the 'Vault' exhibit at the Natural History Museum in London.[40]

During the Second World War, the Crown Jewels were moved from their home at the Tower of London to Windsor Castle.[41] In 1990, The Sunday Telegraph, citing a biography of the French army general, Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, by his widow, Simonne, reported that George VI hid the Koh-i-Noor at the bottom of a pond or lake near Windsor Castle, about 32 km (20 miles) outside London, where it remained until after the war. The only people who knew of the hiding place were the king and his librarian, Sir Owen Morshead, who apparently revealed the secret to the general and his wife on their visit to England in 1949.[42]

Ownership dispute

The Government of India, believing the gem was rightfully theirs, first demanded the return of the Koh-i-Noor as soon as independence was granted in 1947. A second request followed in 1953, the year of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Each time, the British government rejected the claims, saying that ownership was non-negotiable.[34]

In 1976, Pakistan asserted its ownership of the diamond, saying its return would be "a convincing demonstration of the spirit that moved Britain voluntarily to shed its imperial encumbrances and lead the process of decolonisation". In a letter to the Prime Minister of Pakistan, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, James Callaghan, wrote, "I need not remind you of the various hands through which the stone has passed over the past two centuries, nor that explicit provision for its transfer to the British crown was made in the peace treaty with the Maharajah of Lahore in 1849. I could not advise Her Majesty that it should be surrendered".[43]

In 2000, several members of the Indian Parliament signed a letter calling for the diamond to be given back to India, claiming it was taken illegally.[24] British officials said that a variety of claims meant it was impossible to establish the gem's original owner. Later that year, the Taliban's foreign affairs spokesman, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, said the Koh-i-Noor was the legitimate property of Afghanistan, and demanded for it to be handed over to the regime as soon as possible. "The history of the diamond shows it was taken from us (Afghanistan) to India, and from there to Britain. We have a much better claim than the Indians", he said.[44]

In July 2010, while visiting India, David Cameron, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, said of returning the diamond, "If you say yes to one you suddenly find the British Museum would be empty. I am afraid to say, it is going to have to stay put".[34] On a subsequent visit in February 2013, he said, "They're not having that back".[45]

In April 2016, the Indian Culture Ministry stated it would make "all possible efforts" to arrange the return of the Koh-i-Noor to India.[46] It was despite the Indian Government earlier conceding that the diamond was a gift. The Solicitor General of India had made the announcement before the Supreme Court of India due to public interest litigation by a campaign group.[47] He said "It was given voluntarily by Ranjit Singh to the British as compensation for help in the Sikh wars. The Koh-i-Noor is not a stolen object".[48]

In popular culture

The Koh-i-nor made its first appearance in popular culture in The Moonstone (1868) by Wilkie Collins, a 19th-century British epistolary novel, generally considered the first full length detective novel in the English language. In his preface to the first edition of the book, Collins states he based his Moonstone on the histories of two stones, the Orlov, a diamond set in the Russian Imperial Sceptre, and "the famous Koh-i-nor".[49] In "A Note on Sources" in the 1966 Penguin edition of The Moonstone, J. I. M. Stewart states that Collins used G. C. King's Natural History of Precious Stones (1865) to research the history of the Koh-i-Noor.[50][51]

The Koh-i-noor is featured in the plot of the 1990 novel Flashman and the Mountain of Light and the 2006 Doctor Who episode Tooth and Claw.

The Koh-i-Noor appears as a Treasure Demon (a class of enemies based on valuable objects) in the 2016 video game Persona 5.

Rahsaan Noor's adventure film Curse of the Kohinoor is scheduled for a worldwide release in the summer of 2017.[52]

See also

- Noor-ul-Ain ("Light of the Eye")

- Cullinan Diamond

- List of diamonds

References

- ↑ Kenneth J. Mears (1988). The Tower of London: 900 Years of English History. Phaidon. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-7148-2527-4.

- ↑ "Crown Jewels". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 211. United Kingdom: House of Commons. 16 July 1992. col. 944W.

- ↑ Hubert Bari; Violaine Sautter (2001). Diamonds: In the Heart of the Earth, in the Heart of Stars, at the Heart of Power. Vilo International. p. 178. ISBN 978-2-84576-032-5.

- 1 2 Claude Blair; Shirley Bury; Arthur Grimwade; E. Alan Jobbins; Donald King; Ronald Lightbown; Kenneth Scarratt; Roger Harding (1998). The Crown Jewels: The History of the Coronation Regalia in the Jewel House of the Tower of London. 2. The Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-701359-9.

- ↑ Kenneth J. Mears; Simon Thurley; Claire Murphy (1994). The Crown Jewels. Historic Royal Palaces Agency. p. 27. ASIN B000HHY1ZQ.

- ↑ Catherine B. Asher; Cynthia Talbot (2006). India Before Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-521-80904-7.

- ↑ James Gribble; Mary Pendlebury (1896). A History of the Deccan. 1. Luzac and Company. p. 7.

- ↑ R. A. Donkin (1998). Beyond Price: Pearls and Pearl-fishing: Origins to the Age of Discoveries. American Philosophical Society. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-87169-224-5.

- ↑ Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (1998). A History of India (3 ed.). Psychology Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-415-15482-6.

- ↑ Fanselow, Frank S. (1989). "Muslim Society in Tamil Nadu (India): An Historical Perspective". Journal Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs. 10 (1): 264–289.

- ↑ Jean Marie Lafont (2002). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: Lord of the Five Rivers. Oxford University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-19-566111-8.

- ↑ Leela Kohli (30 May 1953). "Fascinating history of world's best diamonds". The Northern Star. Lismore, New South Wales: National Library of Australia. p. 6. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ Sir George Younghusband; Cyril Davenport (1919). The Crown Jewels of England. Cassell & Co. pp. 53–55. ASIN B00086FM86.

- ↑ "Koh-i-Noor: Six myths about a priceless diamond", from BBC, 9 December 2016

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cyril Davenport (1897). The English Regalia. K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. pp. 57–59.

- ↑ Victor Argenzio (1977). Crystal Clear: The Story of Diamonds. David McKay Co. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-679-20317-9.

- ↑ Anita Anand (16 February 2016). "The Koh-i-Noor diamond is in Britain illegally. But it should still stay there". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ↑ Michael Axworthy (2008). Iran: Empire of the Mind: A History from Zoroaster to the Present Day. Penguin Books. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-14-190341-5.

- 1 2 UK Consumer Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)", MeasuringWorth.com.

- ↑ Axworthy, p. 159.

- ↑ The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies. 27. W. H. Allen & Co. 1838. p. 177.

- ↑ William Dalrymple (2012). Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan. Bloomsbury. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-408-8183-05.

- ↑ P. N. Rastogi (1986). Ethnic Tensions in Indian Society: Explanation, Prediction, Monitoring and Control. Mittal Publications. p. 145.

- 1 2 "Indian MPs demand Koh-i-Noor's return". BBC News. 26 April 2000. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- ↑ Lady Lena Campbell Login (1890). Sir John Login and Duleep Singh. Patiala: Languages Dept, Punjab. p. 126.

- ↑ James Andrew Broun-Ramsay (1911). Private Letters (2 ed.). India: Blackwood. pp. 87–88.

- 1 2 Anna Keay (2011). The Crown Jewels: The Official Illustrated History. Thames & Hudson. pp. 156–158. ISBN 978-0-500-51575-4.

- ↑ William Riddell Birdwood (1946). In My Time: Recollections and Anecdotes. Skeffington & Son. p. 85.

- ↑ Dena K. Tarshis (2000). "The Koh-i-Noor diamond and its glass replica at the Crystal Palace exhibition". Journal of Glass Studies. Corning Museum of Glass. 42: 138. ISSN 0075-4250. JSTOR 24191006.

- ↑ Robert Ellis (1851). The Great Exhibition: Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue. Spicer Brothers. p. 696.

- ↑ The Bankers' Magazine. 6. Warren, Gorham & Lamont. 1852. p. 246.

- ↑ John Tallis, ed. (1852). Tallis's History and Description of the Crystal Palace and the Exhibition of the World's Industry in 1851. London Printing & Publishing Co. p. 150.

- ↑ The Illustrated London News. Illustrated London News & Sketch Ltd. 24 July 1852. p. 54.

- 1 2 3 4 Neil Tweedie (29 July 2010). "The Koh-i-Noor: diamond robbery?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ↑ Nicholas Tarling (April 1981). "The Wars of British Succession" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of History. University of Auckland. 15: 27. ISSN 0028-8322.

- ↑ "Queen Mary's Crown". Royal Collection. 31704.

- ↑ "Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother's Crown". Royal Collection. 31703.

- ↑ "Priceless gem in Queen Mother's crown". BBC News. 4 April 2002. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ↑ "The Crown Jewels: Famous Diamonds". Historic Royal Palaces. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ↑ "Glittering finale for the Museum of Life documentary". Natural History Museum. 22 April 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ↑ Elizabeth Hennessy (1992). A Domestic History of the Bank of England, 1930–1960. Cambridge University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-521-39140-5.

- ↑ Associated Press (10 June 1990). "British Crown Jewels hidden in lake in World World II, newspaper says". AP News Archive. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ↑ Pakistan Horizon. 29. Pakistan Institute of International Affairs. 1976. p. 267.

- ↑ Luke Harding (5 November 2000). "Taliban asks the Queen to return Koh-i-Noor gem". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ↑ Nelson, Sara C. (21 February 2013). "Koh-i-Noor diamond will not be returned to India, David Cameron insists". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ Nida Najar (20 April 2016). "India says it wants one of the Crown Jewels back from Britain". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ "Koh-i-Noor not stolen but gifted: Centre". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. 18 April 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ↑ "India: Koh-i-Noor gem given to UK, not stolen". Sky News. 19 April 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ Collins, Wilkie. [quotation, the preface, 1868] The Moonstone – A Novel. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1874.

- ↑ "Review: The Natural History of Precious Stones and Gems and of the Precious Metals by C. W. King". The Art Journal: p. 323. October 1865.

- ↑ The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876) The Victorian Web.

- ↑ "Aref Syed to Make His International Debut". The Daily Star. September 3, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Koh-i-Noor Diamond. |

-

Works related to the Koh-i-Noor at Wikisource

Works related to the Koh-i-Noor at Wikisource - The Koh-i-Noor Diamond at h2g2