Kite (geometry)

| Kite | |

|---|---|

A kite, showing its pairs of equal length sides and its inscribed circle. | |

| Type | Quadrilateral |

| Edges and vertices | 4 |

| Symmetry group | D1 (*) |

| Dual polygon | Isosceles trapezoid |

In Euclidean geometry, a kite is a quadrilateral whose four sides can be grouped into two pairs of equal-length sides that are adjacent to each other. In contrast, a parallelogram also has two pairs of equal-length sides, but they are opposite to each other rather than adjacent. Kite quadrilaterals are named for the wind-blown, flying kites, which often have this shape and which are in turn named for a bird. Kites are also known as deltoids, but the word "deltoid" may also refer to a deltoid curve, an unrelated geometric object.

A kite, as defined above, may be either convex or concave, but the word "kite" is often restricted to the convex variety. A concave kite is sometimes called a "dart" or "arrowhead", and is a type of pseudotriangle.

Special cases

If all four sides of a kite have the same length (that is, if the kite is equilateral), it must be a rhombus.

If a kite is equiangular, meaning that all four of its angles are equal, then it must also be equilateral and thus a square. A kite with three equal 108° angles and one 36° angle forms the convex hull of the lute of Pythagoras.[1]

The kites that are also cyclic quadrilaterals (i.e. the kites that can be inscribed in a circle) are exactly the ones formed from two congruent right triangles. That is, for these kites the two equal angles on opposite sides of the symmetry axis are each 90 degrees.[2] These shapes are called right kites[3] and they are in fact bicentric quadrilaterals (below to the left). Among all the bicentric quadrilaterals with a given two circle radii, the one with maximum area is a right kite.[4]

There are only eight polygons that can tile the plane in such a way that reflecting any tile across any one of its edges produces another tile; one of them is a right kite, with 60°, 90°, and 120° angles. The tiling that it produces by its reflections is the deltoidal trihexagonal tiling.[5]

A right kite |

An equidiagonal kite inscribed in a Reuleaux triangle |

Among all quadrilaterals, the shape that has the greatest ratio of its perimeter to its diameter is an equidiagonal kite with angles π/3, 5π/12, 5π/6, 5π/12. Its four vertices lie at the three corners and one of the side midpoints of the Reuleaux triangle (above to the right).[6]

In non-Euclidean geometry, a Lambert quadrilateral is a right kite with three right angles.[7]

Characterizations

A quadrilateral is a kite if and only if any one of the following conditions is true:

- Two disjoint pairs of adjacent sides are equal (by definition).

- One diagonal is the perpendicular bisector of the other diagonal.[8] (In the concave case it is the extension of one of the diagonals.)

- One diagonal is a line of symmetry (it divides the quadrilateral into two congruent triangles that are mirror images of each other).[9]

- One diagonal bisects a pair of opposite angles.[9]

Symmetry

The kites are the quadrilaterals that have an axis of symmetry along one of their diagonals.[10] Any non-self-crossing quadrilateral that has an axis of symmetry must be either a kite (if the axis of symmetry is a diagonal) or an isosceles trapezoid (if the axis of symmetry passes through the midpoints of two sides); these include as special cases the rhombus and the rectangle respectively, which have two axes of symmetry each, and the square which is both a kite and an isosceles trapezoid and has four axes of symmetry.[10] If crossings are allowed, the list of quadrilaterals with axes of symmetry must be expanded to also include the antiparallelograms.

Basic properties

Every kite is orthodiagonal, meaning that its two diagonals are at right angles to each other. Moreover, one of the two diagonals (the symmetry axis) is the perpendicular bisector of the other, and is also the angle bisector of the two angles it meets.[10]

One of the two diagonals of a convex kite divides it into two isosceles triangles; the other (the axis of symmetry) divides the kite into two congruent triangles.[10] The two interior angles of a kite that are on opposite sides of the symmetry axis are equal.

Area

As is true more generally for any orthodiagonal quadrilateral, the area A of a kite may be calculated as half the product of the lengths of the diagonals p and q:

Alternatively, if a and b are the lengths of two unequal sides, and θ is the angle between unequal sides, then the area is

Tangent circles

Every convex kite has an inscribed circle; that is, there exists a circle that is tangent to all four sides. Therefore, every convex kite is a tangential quadrilateral. Additionally, if a convex kite is not a rhombus, there is another circle, outside the kite, tangent to the lines that pass through its four sides; therefore, every convex kite that is not a rhombus is an ex-tangential quadrilateral.

For every concave kite there exist two circles tangent to all four (possibly extended) sides: one is interior to the kite and touches the two sides opposite from the concave angle, while the other circle is exterior to the kite and touches the kite on the two edges incident to the concave angle.[11]

Dual properties

Kites and isosceles trapezoids are dual: the polar figure of a kite is an isosceles trapezoid, and vice versa.[12] The side-angle duality of kites and isosceles trapezoids are compared in the table below.[9]

| Isosceles trapezoid | Kite |

|---|---|

| Two pairs of equal adjacent angles | Two pairs of equal adjacent sides |

| One pair of equal opposite sides | One pair of equal opposite angles |

| An axis of symmetry through one pair of opposite sides | An axis of symmetry through one pair of opposite angles |

| Circumscribed circle | Inscribed circle |

Tilings and polyhedra

All kites tile the plane by repeated inversion around the midpoints of their edges, as do more generally all quadrilaterals. A kite with angles π/3, π/2, 2π/3, π/2 can also tile the plane by repeated reflection across its edges; the resulting tessellation, the deltoidal trihexagonal tiling, superposes a tessellation of the plane by regular hexagons and isosceles triangles.[13]

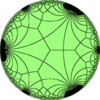

The deltoidal icositetrahedron, deltoidal hexecontahedron, and trapezohedron are polyhedra with congruent kite-shaped facets. There are an infinite number of uniform tilings of the hyperbolic plane by kites, the simplest of which is the deltoidal triheptagonal tiling.

Kites and darts in which the two isosceles triangles forming the kite have apex angles of 2π/5 and 4π/5 represent one of two sets of essential tiles in the Penrose tiling, an aperiodic tiling of the plane discovered by mathematical physicist Roger Penrose.

Face-transivive self-tesselation of the sphere, Euclidean plane, and hyperbolic plane with kites occurs as uniform duals: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() for Coxeter group [p,q], with any set of p,q between 3 and infinity, as this table partially shows up to q=6. When p=q, the kites become rhombi.

for Coxeter group [p,q], with any set of p,q between 3 and infinity, as this table partially shows up to q=6. When p=q, the kites become rhombi.

| Polyhedra | Euclidean | Hyperbolic tilings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

V4.3.4.3 |

V4.3.4.4 |

V4.3.4.5 |

V4.3.4.6 |

V4.3.4.7 |

V4.3.4.8 |

... |  V4.3.4.∞ |

| Polyhedra | Euclidean | Hyperbolic tilings | |||||

V4.4.4.3 |

V4.4.4.4 |

V4.4.4.5 |

V4.4.4.6 |

V4.4.4.7 |

V4.4.4.8 |

... |  V4.4.4.∞ |

| Polyhedra | Hyperbolic tilings | ||||||

V4.3.4.5 |

V4.4.4.5 |

V4.5.4.5 |

V4.6.4.5 |

V4.7.4.5 | V4.8.4.5 | ... | V4.∞.4.5 |

| Euclidean | Hyperbolic tilings | ||||||

V4.3.4.6 |

V4.4.4.6 |

V4.5.4.6 |

V4.6.4.6 |

V4.7.4.6 |  V4.8.4.6 |

... |  V4.∞.4.6 |

| Hyperbolic tilings | |||||||

V4.3.4.7 |

V4.4.4.7 | V4.5.4.7 | V4.6.4.7 | V4.7.4.7 | V4.8.4.7 | ... | V4.∞.4.7 |

| Hyperbolic tilings | |||||||

V4.3.4.8 |

V4.4.4.8 |

V4.5.4.8 |  V4.6.4.8 |

V4.7.4.8 |  V4.8.4.8 |

... |  V4.∞.4.8 |

Conditions for when a tangential quadrilateral is a kite

A tangential quadrilateral is a kite if and only if any one of the following conditions is true:[14]

- The area is one half the product of the diagonals.

- The diagonals are perpendicular. (Thus the kites are exactly the quadrilaterals that are both tangential and orthodiagonal.)

- The two line segments connecting opposite points of tangency have equal length.

- One pair of opposite tangent lengths have equal length.

- The bimedians have equal length.

- The products of opposite sides are equal.

- The center of the incircle lies on a line of symmetry that is also a diagonal.

If the diagonals in a tangential quadrilateral ABCD intersect at P, and the incircles in triangles ABP, BCP, CDP, DAP have radii r1, r2, r3, and r4 respectively, then the quadrilateral is a kite if and only if[14]

If the excircles to the same four triangles opposite the vertex P have radii R1, R2, R3, and R4 respectively, then the quadrilateral is a kite if and only if[14]

References

- ↑ Darling, David (2004), The Universal Book of Mathematics: From Abracadabra to Zeno's Paradoxes, John Wiley & Sons, p. 260, ISBN 9780471667001.

- ↑ Gant, P. (1944), "A note on quadrilaterals", Mathematical Gazette, The Mathematical Association, 28 (278): 29–30, JSTOR 3607362, doi:10.2307/3607362.

- ↑ De Villiers, Michael (1994), "The role and function of a hierarchical classification of quadrilaterals", For the Learning of Mathematics, 14 (1): 11–18, JSTOR 40248098

- ↑ Josefsson, Martin (2012), "Maximal area of a bicentric quadrilateral" (PDF), Forum Geometricorum, 12: 237–241, MR 2990945.

- ↑ Kirby, Matthew; Umble, Ronald (2011), "Edge tessellations and stamp folding puzzles", Mathematics Magazine, 84 (4): 283–289, MR 2843659, arXiv:0908.3257

, doi:10.4169/math.mag.84.4.283.

, doi:10.4169/math.mag.84.4.283. - ↑ Ball, D.G. (1973), "A generalisation of π", Mathematical Gazette, 57 (402): 298–303, doi:10.2307/3616052; Griffiths, David; Culpin, David (1975), "Pi-optimal polygons", Mathematical Gazette, 59 (409): 165–175, doi:10.2307/3617699.

- ↑ Eves, Howard Whitley (1995), College Geometry, Jones & Bartlett Learning, p. 245, ISBN 9780867204759.

- ↑ Zalman Usiskin and Jennifer Griffin, "The Classification of Quadrilaterals. A Study of Definition", Information Age Publishing, 2008, pp. 49-52.

- 1 2 3 Michael de Villiers, Some Adventures in Euclidean Geometry, ISBN 978-0-557-10295-2, 2009, pp. 16, 55.

- 1 2 3 4 Halsted, George Bruce (1896), "Chapter XIV. Symmetrical Quadrilaterals", Elementary Synthetic Geometry, J. Wiley & sons, pp. 49–53.

- ↑ Wheeler, Roger F. (1958), "Quadrilaterals", Mathematical Gazette, The Mathematical Association, 42 (342): 275–276, JSTOR 3610439, doi:10.2307/3610439.

- ↑ Robertson, S.A. (1977), "Classifying triangles and quadrilaterals", Mathematical Gazette, The Mathematical Association, 61 (415): 38–49, JSTOR 3617441, doi:10.2307/3617441.

- ↑ See Weisstein, Eric W. "Polykite". MathWorld. .

- 1 2 3 Josefsson, Martin (2011), "When is a Tangential Quadrilateral a Kite?" (PDF), Forum Geometricorum, 11: 165–174.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Deltoids. |

- Kite definition and area formulae with interactive animations at Mathopenref.com