Kisra legend

The Kisra legend is a migration story shared by a number of political and ethnic groups in modern Nigeria, Benin, and Cameroon, primarily the Borgu kingdom and the people of the Benue River valley. The migration legend depicts the arrival of a large military force in what is currently Northern Nigeria around the 7th Century AD. The Borgu kingdom claimed direct descent from the leader of this migration and a number of other polities recognize the migration through ceremony and formal regalia. There are a number of different versions of the legend with Kisra sometimes being depicted as a religious and military rival to Muhammad near Mecca around the time that Islam was founded and sometimes as the remnant forces of a Persian king defeated in Egypt. The legend was a key piece of evidence in a number of Hamitic historical theories which argued that the political development of societies in sub-Saharan Africa was the result of contacts with societies from the Middle East (namely Egypt, Rome, and the Byzantine Empire).

The Kisra legend

The legend is shared by many different political and ethnic entities throughout what is currently northern Nigeria and has provided important linkages between these communities. Although the different versions share a similar depiction of a large migration into the area along the Niger river in around the 7th Century. Two of the most prominent versions of the story depict Kisra as a challenger to Muhammad on the Arabian peninsula or as a Persian ruler who suffered a military defeat in Egypt.[1] However, in some versions Kisra is not an individual person but a generalized title for the leader of the migration as it moved across Africa.[2] Versions also differ on other aspects of the story, namely whether or not Kisra himself founded any of the royal lines and the specifics of his death or magical disappearance.[1]

Kisra as challenger to Muhammad

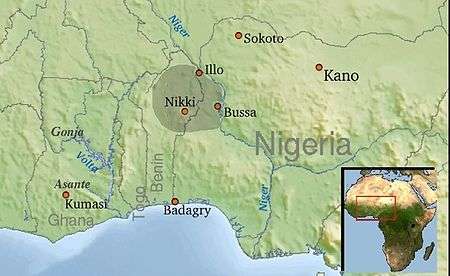

In the most prominent version of the story in the Borgu kingdom, Kisra is depicted as an early political and religious challenger to Muhammad in the area around Mecca.[3] In this version, Kisra was a prominent leader and possessed a number of magical powers. However, during his rule, a seer foresaw that his power would eventually be undermined by a child born within the city who would have divine powers.[4] To prevent this challenge, Kisra exiled all the men of his city on the date that the seer had predicted the baby to be conceived; however, the husband of Aminatu, Kisra's daughter, remained in the city and a son was conceived, Muhammad. As Muhammad grew, he began trying to convert Kisra to Islam, but the ruler resisted. Eventually, this resulted in open warfare between Muhammad and Kisra over religious issues and Kisra won the initial conflict. However, as Muhammad fled to a baobab tree he was provided divine assistance for his escape and to reorganize his forces.[3] Seeing that the tables had turned, Kisra and his followers left the Arabian peninsula, eventually reaching the Niger river.[5] Kisra's party visited many of the villages in the area before eventually founding the Borgu kingdom. In some versions of the legend, Kisra's oldest son Woru (or sometimes Kisra himself) founded the city of Bussa, which would become the capital of Borgu. Kisra's younger sons founded Nikki, founded by Shabi, and Illo, founded by Bio.[6] In later versions, this order of foundation of the main cities of the Borgu kingdom is changed.[6] The legend became crucial in the Borgu kingdom in uniting the different cities,[7] legitimizing the ruling dynasty (the Wasangari),[6] and providing an ideological distinction between Borgu and the Islamic states in the area.[3]

Kisra as Persian king

In 1909, the German anthropologist Leo Frobenius compiled an aggregate version of the Kisra legend from informants in the Benue river valley. This version depicts Kisra not as a challenger to Mohammad, but instead as a Persian king who suffered a military defeat in Egypt to a Byzantine army.[8] Following this defeat, Kisra and his army were unable to return to Persia and had to work further into Africa. His army settled briefly in Nubia and Ethiopia where Kisra joined forces with a powerful king in the region, Napata, to conquer lands to the West. His army migrated into the Niger river region and then followed a similar route as that described above with Kisra's party visiting a number of communities in the area and eventually settling in the Borgu area.[8]

Polities linked to Kisra's migration

Many communities in the area have some connection to the Kisra migration and the story is used in much of the folklore of the region. However, some cities claim direct connection to the Kisra. These include:

- Borgu kingdom, the cities of Bussa, Nikki, and Illo claim to have been founded by Kisra and his sons.[9]

- Gunji, believed to be the location where Kisra's three sons divided from one another to found the three cities of the Borgu kingdom.[9]

- Karissen, a cipu city east of Yauri, Nigeria in the Benue river area, legends say that the people in the area named Kisra's grandson, Damasa, as their king.[10]

- Kebbi Emirate, has a long tradition of the Kisra legend,[11] and the royal title in Kebbi of "Kanta" may be derived from the title Kisra.[12]

- Wukari, the king holds an ancient sword and spear said to be gifts from Kisra when he visited the area.[13]

- Zaria, in some versions this city was founded by Kisra's forces before it was destroyed by the Bornu kingdom.[9]

Basis of the legend

Anthropologists and historians have conducted significant oral histories and material research to identify any correspondence of key parts of the legend. These studies generally agree that a migration into the area did occur around the seventh century.[7] Frobenius argued that the figure of Kisra was possibly the Persian king Khosrau II or Chosroes.[14] Some parts of the historical account do correspond with the timeline of Khosrau II who conquered Egypt in the early 7th century before being defeated by a Byzantine army and it is considered possible that some parts of the army were unable to return to Persia and so journeyed through Africa.[15] Flora Shaw in contrast argued that Kisra was a mistranslation of "Christ" and that the migration was largely of Christian origin.[14] C.K. Moss instead contends that Kisra was more likely a Songhai or Mosi king who rose to prominence in the 15th century.[16]

In summarizing this work, historian Daniel McCall finds that although there is no clear evidence disproving any of these arguments, there are significant problems with all of them, including: the migrating army is said to use armor not used by the Persians at that time, a lack of ecclesiastical historical corroboration, and no Christian or Mithraic symbols came with the migration.[17]

Importance

The Kisra legend is a very important folklore in many of the communities of northern Nigeria. The legend was a key part of developing clear cultural identity in Borgu and Kebbi as they resisted Songhai and Fulani dominance to the north.[12] In addition, the shared Kisra legend facilitated trade and peace treaties between the various ethnic and political communities in the area.[12] Most notably, Borgu and Bornu and Borgu and Kebbi maintained productive trade relations for centuries often facilitated by Kisra traditions of gift exchange.[11][12] After British control of Nigeria around 1900, administrative change and competition in the new governmental structures led to changes in the legend for each different community.[18]

The legend played a key role in many (now largely discredited) Hamitic theories of African political and social development.[15] These theories argued that political development, namely the formation of complex states, had its origins in migrations of people from the Middle East or of Christian influences (often Coptic).[1] The Kisra legend, and particularly the hypothesis that Kisra was actually Khosrau II, was seen as clear evidence for Egyptian, Nubian, Byzantine, or Persian influence into the development of West Africa. Without additional historical evidence though the importance of the Kisra legend was often overemphasized.[19][20]

References

- 1 2 3 Stevens Jr. 1975, p. 190.

- ↑ McCall 1968, p. 262.

- 1 2 3 Adekunle 1994, p. 545.

- ↑ Stewart 1980, p. 61.

- ↑ Stewart 1980, pp. 61-63.

- 1 2 3 Akinwumi 1998, p. 1.

- 1 2 Stevens Jr. 1975, p. 189.

- 1 2 Stewart 1980, p. 63.

- 1 2 3 Stewart 1980, p. 55.

- ↑ The Acipu People 2011.

- 1 2 Stevens Jr. 1975, p. 194.

- 1 2 3 4 Adenkule 2004, p. 53.

- 1 2 Stewart 1980, p. 56.

- 1 2 McCall 1968, p. 258.

- 1 2 Fage 1969, p. 9.

- ↑ McCall 1968, p. 259.

- ↑ McCall 1968, p. 275.

- ↑ Akinwumi 1998, p. 7.

- ↑ McCall 1968, p. 270.

- ↑ Fage 1969, p. 10.

Bibliography

Books and Journal Articles

- Adekunle, Julius O. (1994). "On Oral Tradition and History: Studies on Nigerian Borgu". Anthropos. 89 (4/6): 543–551. JSTOR 40463023.

- Adenkule, Julius O. (2004). Politics and Society in Nigeria's Middlebelt: Borgu and the Emergence of a Political Identity. Africa World Press. ISBN 978-1-59221-096-1. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- Akinwumi, Olayemi (1998). "Oral Tradition in Changing Political Contexts: The Kisra Legend in Northern Borgu". History in Africa. 25: 1–7. doi:10.2307/3172177.

- Fage, J.D. (1969). A History of West Africa. London: Cambridge University Press.

- McCall, Daniel F. (1968). "Kisra, Chosroes, Christ, Etc.". African Historical Studies. 1 (2): 255–277. doi:10.2307/216399.

- Stevens Jr., Phillip (1975). "The Kisra Legend and the Distortion of Historical Tradition". The Journal of African History. 16 (2): 185–200. doi:10.1017/S0021853700001110.

- Stewart, Marjorie Helen (1980). "The Kisra Legend as Oral History". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 13 (1): 51–70. doi:10.2307/218372.

Web Resources

- "The Acipu people". The Cicipu language. 2011. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.