Jack Kirby

| Jack Kirby | |

|---|---|

Kirby in 1992 | |

| Born |

Jacob Kurtzberg August 28, 1917 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

February 6, 1994 (aged 76) Thousand Oaks, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) |

|

| Pseudonym(s) | Jack Curtiss, Curt Davis, Lance Kirby, Ted Grey, Charles Nicholas, Fred Sande, Teddy |

Notable works | The Avengers, Captain America, Fantastic Four, Fourth World, Hulk, Kamandi, Manhunter, Newsboy Legion, Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos, Silver Surfer, Thor, X-Men |

| Awards | Alley Award, Best Pencil Artist (1967), plus many awards for individual stories, Shazam Award, Special Achievement by an Individual (1971) |

| Spouse(s) | Roz Goldstein (m. 1942) |

| Children | 4 |

Jack Kirby (/ˈkɜːrbi/; born Jacob Kurtzberg /ˈkɜːrtsbɜːrɡ/; August 28, 1917 – February 6, 1994),[1] was an American comic book artist, writer, and editor, widely regarded as one of the medium's major innovators and one of its most prolific and influential creators.

Kirby grew up in New York City, and learned to draw cartoon figures by tracing characters from comic strips and editorial cartoons. He entered the nascent comics industry in the 1930s, drawing various comics features under different pen names, including Jack Curtiss, before ultimately settling on Jack Kirby. In 1940, he and writer-editor Joe Simon created the highly successful superhero character Captain America for Timely Comics, predecessor of Marvel Comics. During the 1940s, Kirby, regularly teamed with Simon, created numerous characters for that company and for National Comics Publications, later to become DC Comics.

After serving in World War II, Kirby produced work for a number of publishers, including DC, Harvey Comics and Hillman Periodicals. At Crestwood Publications he and Simon created the genre of romance comics and later founded their own short-lived comic company, Mainline Publications. Ultimately, Kirby found himself at Timely's 1950s iteration, Atlas Comics, which in the next decade became Marvel. There, in the 1960s, Kirby and writer-editor Stan Lee co-created many of the company's major characters, including the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, and the Hulk. The Lee–Kirby titles garnered high sales and critical acclaim, but in 1970, feeling he had been treated unfairly, Kirby left the company for rival DC.

At DC, Kirby created his Fourth World saga, which spanned several comics titles. While these series proved commercially unsuccessful and were canceled, the Fourth World's New Gods have continued as a significant part of the DC Universe. Kirby returned to Marvel briefly in the mid-to-late 1970s, then ventured into television animation and independent comics. In his later years, Kirby, who has been called "the William Blake of comics",[2] began receiving great recognition in the mainstream press for his career accomplishments, and in 1987 he was one of the three inaugural inductees of the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame.

Kirby was married to Rosalind Goldstein in 1942. They had four children, and remained married until his death from heart failure in 1994, at the age of 76. The Jack Kirby Awards and Jack Kirby Hall of Fame were named in his honor.

Life and career

Early life (1917–1935)

Jack Kirby was born Jacob Kurtzberg on August 28, 1917, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in New York City, where he was raised.[3] His parents, Rose (Bernstein) and Benjamin Kurtzberg,[3] were Austrian Jewish immigrants, and his father earned a living as a garment factory worker.[4] In his youth, Kirby desired to escape his neighborhood. He liked to draw, and sought out places he could learn more about art.[5] Essentially self-taught,[6] Kirby cited among his influences the comic strip artists Milton Caniff, Hal Foster, and Alex Raymond, as well as such editorial cartoonists as C. H. Sykes, "Ding" Darling, and Rollin Kirby.[6] He was rejected by the Educational Alliance because he drew "too fast with charcoal", according to Kirby. He later found an outlet for his skills by drawing cartoons for the newspaper of the Boys Brotherhood Republic, a "miniature city" on East 3rd Street where street kids ran their own government.[7]

At age 14, Kirby enrolled at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, leaving after a week. "I wasn't the kind of student that Pratt was looking for. They wanted people who would work on something forever. I didn't want to work on any project forever. I intended to get things done".[8]

Entry into comics (1936–1940)

Kirby joined the Lincoln Newspaper Syndicate in 1936, working there on newspaper comic strips and on single-panel advice cartoons such as Your Health Comes First!!! (under the pseudonym Jack Curtiss). He remained until late 1939, when he began working for the movie animation company Fleischer Studios as an inbetweener (an artist who fills in the action between major-movement frames) on Popeye cartoons. "I went from Lincoln to Fleischer," he recalled. "From Fleischer I had to get out in a hurry because I couldn't take that kind of thing," describing it as "a factory in a sense, like my father's factory. They were manufacturing pictures."[9]

Around that time, the American comic book industry was booming. Kirby began writing and drawing for the comic-book packager Eisner & Iger, one of a handful of firms creating comics on demand for publishers. Through that company, Kirby did what he remembers as his first comic book work, for Wild Boy Magazine.[10] This included such strips as the science fiction adventure "The Diary of Dr. Hayward" (under the pseudonym Curt Davis), the Western crimefighter feature "Wilton of the West" (as Fred Sande), the swashbuckler adventure "The Count of Monte Cristo" (again as Jack Curtiss), and the humor features "Abdul Jones" (as Ted Grey) and '"Socko the Seadog" (as Teddy), all variously for Jumbo Comics and other Eisner-Iger clients.[11] He first used the surname Kirby as the pseudonymous Lance Kirby in two "Lone Rider" Western stories in Eastern Color Printing's Famous Funnies #63-64 (Oct.-Nov. 1939).[11] He ultimately settled on the pen name Jack Kirby because it reminded him of actor James Cagney. However, he took offense to those who suggested he changed his name in order to hide his Jewish heritage.[12]

In the summer of 1940, Kirby and his family moved to Brooklyn. There, Kirby met Rosalind "Roz" Goldstein, who lived in the same apartment building. The pair began dating soon afterward.[13] Kirby proposed to Goldstein on her eighteenth birthday, and the two became engaged.[14]

Partnership with Joe Simon

Kirby moved on to comic-book publisher and newspaper syndicator Fox Feature Syndicate, earning a then-reasonable $15-a-week salary. He began to explore superhero narrative with the comic strip The Blue Beetle, published from January to March 1940, starring a character created by the pseudonymous Charles Nicholas, a house name that Kirby retained for the three-month-long strip. During this time, Kirby met and began collaborating with cartoonist and Fox editor Joe Simon, who in addition to his staff work continued to freelance. Simon recalled in 1988, "I loved Jack's work and the first time I saw it I couldn't believe what I was seeing. He asked if we could do some freelance work together. I was delighted and I took him over to my little office. We worked from the second issue of Blue Bolt through... about 25 years."[15]

After leaving Fox and landing at pulp magazine publisher Martin Goodman's Timely Comics (later to become Marvel Comics), Simon and Kirby created the patriotic superhero Captain America in late 1940.[16] Simon, who became the company's editor, with Kirby as art director, said he negotiated with Goodman to give the duo 25 percent of the profits from the feature.[17] The first issue of Captain America Comics, released in early 1941,[18] sold out in days, and the second issue's print run was set at over a million copies. The title's success established the team as a notable creative force in the industry.[19] After the first issue was published, Simon asked Kirby to join the Timely staff as the company's art director.[20]

With the success of the Captain America character, Simon said he felt that Goodman was not paying the pair the promised percentage of profits, and so sought work for the two of them at National Comics Publications (later renamed DC Comics).[17] Kirby and Simon negotiated a deal that would pay them a combined $500 a week, as opposed to the $75 and $85 they respectively earned at Timely.[21] The pair feared Goodman would not pay them if he found they were moving to National, but many people knew of their plan, including Timely editorial assistant, Stan Lee.[22] When Goodman eventually discovered it, he told Simon and Kirby to leave after finishing work on Captain America Comics #10.[22]

Kirby and Simon spent their first weeks at National trying to devise new characters while the company sought how best to utilize the pair.[23] After a few failed editor-assigned ghosting assignments, National's Jack Liebowitz told them to "just do what you want". The pair then revamped the Sandman feature in Adventure Comics and created the superhero Manhunter.[24][25] In July 1942 they began the Boy Commandos feature. The ongoing "kid gang" series of the same name, launched later that same year, was the creative team's first National feature to graduate into its own title.[26] It sold over a million copies a month, becoming National's third best-selling title.[27] They scored a hit with the homefront kid-gang team, the Newsboy Legion, featuring in Star-Spangled Comics.[28] In 2010, DC Comics writer and executive Paul Levitz observed that "Like Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the creative team of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby was a mark of quality and a proven track record."[29]

Marriage and World War II (1943–1945)

Kirby married Roz Goldstein on May 23, 1942.[30] The couple had four children together: Susan (b. December 6, 1945),[31] Neal (b. May 1948),[32] Barbara (b. November 1952),[33] and Lisa (b. September 1960).[31][34]

With World War II underway, Liebowitz expected that Simon and Kirby would be drafted, so he asked the artists to create an inventory of material to be published in their absence. The pair hired writers, inkers, letterers, and colorists in order to create a year's worth of material.[27] Kirby was drafted into the U.S. Army on June 7, 1943.[35] After basic training at Camp Stewart, near Savannah, Georgia, he was assigned to Company F of the 11th Infantry Regiment.[36] He landed on Omaha Beach in Normandy on August 23, 1944, two-and-a-half months after D-Day,[36] though Kirby's reminiscences would place his arrival just 10 days after.[35] Kirby recalled that a lieutenant, learning that comics artist Kirby was in his command, made him a scout who would advance into towns and draw reconnaissance maps and pictures, an extremely dangerous duty.[37]

Kirby and his wife corresponded regularly by v-mail, with Roz sending "him a letter a day" while she worked in a lingerie shop and lived with her mother[38] at 2820 Brighton 7th Street in Brooklyn.[39] During the winter of 1944, Kirby suffered severe frostbite on his lower extremities and was taken to a hospital in London, England, for recovery. Doctors considered amputating Kirby's legs, but he eventually recovered from the frostbite.[40] He returned to the United States in January 1945, assigned to Camp Butner in North Carolina, where he spent the last six months of his service as part of the motor pool. Kirby was honorably discharged as a Private First Class on July 20, 1945, having received a Combat Infantryman Badge and a European/African/Middle Eastern Theater ribbon with Bronze Star Medal.[41][42]

Postwar career (1946–1955)

Simon arranged for work for Kirby and himself at Harvey Comics,[43] where, through the early 1950s, the duo created such titles as the kid-gang adventure Boy Explorers Comics, the kid-gang Western Boys' Ranch, the superhero comic Stuntman, and, in vogue with the fad for 3-D movies, Captain 3-D. Simon and Kirby additionally freelanced for Hillman Periodicals (the crime fiction comic Real Clue Crime) and for Crestwood Publications (Justice Traps The Guilty).[11]

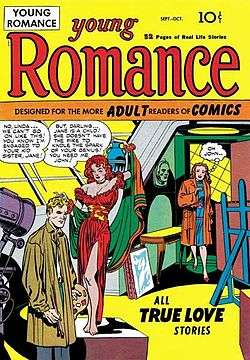

The team found its greatest success in the postwar period by creating romance comics. Simon, inspired by Macfadden Publications' romantic-confession magazine True Story, transplanted the idea to comic books and with Kirby created a first-issue mock-up of Young Romance.[44] Showing it to Crestwood general manager Maurice Rosenfeld, Simon asked for 50% of the comic's profits. Crestwood publishers Teddy Epstein and Mike Bleier agreed,[44] stipulating that the creators would take no money up front.[45] Young Romance #1 (cover-date Oct. 1947) "became Jack and Joe's biggest hit in years".[32] The pioneering title sold a staggering 92% of its print run, inspiring Crestwood to increase the print run by the third issue to triple the initial number of copies.[46] Initially published bimonthly, Young Romance quickly became a monthly title and produced the spin-off Young Love—together the two titles sold two million copies per month, according to Simon[47]—later joined by Young Brides and In Love, the latter "featuring full-length romance stories".[46] Young Romance spawned dozens of imitators from publishers such as Timely, Fawcett, Quality, and Fox Feature Syndicate.[32] Despite the glut, the Simon and Kirby romance titles continued to sell millions of copies a month, which allowed Kirby to buy a house for his family in Mineola, Long Island, New York[32] in 1949, which would be the family's home for the next 20 years, working out of a basement studio 10 feet in width, which the family referred to as "The Dungeon".[48]

Bitter that Timely Comics' 1950s iteration, Atlas Comics, had relaunched Captain America in a new series in 1954, Kirby and Simon created Fighting American. Simon recalled, "We thought we'd show them how to do Captain America".[49] While the comic book initially portrayed the protagonist as an anti-Communist dramatic hero, Simon and Kirby turned the series into a superhero satire with the second issue, in the aftermath of the Army-McCarthy hearings and the public backlash against the Red-baiting U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy.[50]

After Simon (1956–1957)

At the urging of a Crestwood salesman, Kirby and Simon launched their own comics company, Mainline Publications,[50][51] securing a distribution deal with Leader News[52] in late 1953 or early 1954, subletting space from their friend Al Harvey's Harvey Publications at 1860 Broadway.[53] Mainline, which existed from 1954 to 1955, published four titles: the Western Bullseye: Western Scout; the war comic Foxhole, since EC Comics and Atlas Comics were having success with war comics, but promoting theirs as being written and drawn by actual veterans; In Love, since their earlier romance comic Young Love was still being widely imitated; and the crime comic Police Trap, which claimed to be based on genuine accounts by law-enforcement officials.[54] After the duo rearranged and republished artwork from an old Crestwood story in In Love, Crestwood refused to pay the team,[55] who sought an audit of Crestwood's finances. Upon review, the pair's attorney's stated the company owed them $130,000 for work done over the past seven years. Crestwood paid them $10,000 in addition to their recent delayed payments. The partnership between Kirby and Simon had become strained.[56] Simon left the industry for a career in advertising, while Kirby continued to freelance. "He wanted to do other things and I stuck with comics," Kirby recalled in 1971. "It was fine. There was no reason to continue the partnership and we parted friends."[57]

At this point in the mid-1950s, Kirby made a temporary return to the former Timely Comics, now known as Atlas Comics, the direct predecessor of Marvel Comics. Inker Frank Giacoia had approached editor-in-chief Stan Lee for work and suggested he could "get Kirby back here to pencil some stuff."[58] While freelancing for National Comics Publications, the future DC Comics, Kirby drew 20 stories for Atlas from 1956 to 1957: Beginning with the five-page "Mine Field" in Battleground #14 (Nov.1956), Kirby penciled and in some cases inked (with his wife, Roz) and wrote stories of the Western hero Black Rider, the Fu Manchu-like Yellow Claw, and more.[11][59] But in 1957, distribution troubles caused the "Atlas implosion" that resulted in several series being dropped and no new material being assigned for many months. It would be the following year before Kirby returned to the nascent Marvel.

For DC around this time, Kirby co-created with writers Dick and Dave Wood the non-superpowered adventuring quartet the Challengers of the Unknown in Showcase #6 (Feb. 1957),[60] while contributing to such anthologies as House of Mystery.[11] During 30 months freelancing for DC, Kirby drew slightly more than 600 pages, which included 11 six-page Green Arrow stories in World's Finest Comics and Adventure Comics that, in a rarity, Kirby inked himself.[61] Kirby recast the archer as a science-fiction hero, moving him away from his Batman-formula roots, but in the process alienating Green Arrow co-creator Mort Weisinger.[62]

He began drawing a newspaper comic strip, Sky Masters of the Space Force, written by the Wood brothers and initially inked by the unrelated Wally Wood.[63] Kirby left National Comics Publications due largely to a contractual dispute in which editor Jack Schiff, who had been involved in getting Kirby and the Wood brothers the Sky Masters contract, claimed he was due royalties from Kirby's share of the strip's profits. Schiff successfully sued Kirby.[64] Some DC editors had criticized him over art details, such as not drawing "the shoelaces on a cavalryman's boots" and showing a Native American "mounting his horse from the wrong side."[65]

Marvel Comics in the Silver Age (1958–1970)

Several months later, after his split with DC, Kirby began freelancing regularly for Atlas in spite of his lingering resentment of Lee from the 1940s.[66] Because of the poor page rates, Kirby would spend 12 to 14 hours daily at his drawing table at home, producing four to five pages of artwork a day.[67] His first published work at Atlas was the cover of and the seven-page story "I Discovered the Secret of the Flying Saucers" in Strange Worlds #1 (Dec. 1958). Initially with Christopher Rule as his regular inker, and later Dick Ayers, Kirby drew across all genres, from romance comics to war comics to crime comics to Westerns, but made his mark primarily with a series of supernatural-fantasy and science fiction stories featuring giant, drive-in movie-style monsters with names like Groot, the Thing from Planet X;[68] Grottu, King of the Insects;[69] and Fin Fang Foom for the company's many anthology series, such as Amazing Adventures, Strange Tales, Tales to Astonish, Tales of Suspense, and World of Fantasy.[11] His bizarre designs of powerful, unearthly creatures proved a hit with readers. Additionally, he freelanced for Archie Comics' around this time, reuniting briefly with Joe Simon to help develop the series The Fly[70] and The Double Life of Private Strong.[71] Additionally, Kirby drew some issues of Classics Illustrated.[11]

It was at Marvel collaborating with writer and editor-in-chief Lee that Kirby hit his stride once again in superhero comics, beginning with The Fantastic Four #1 (Nov. 1961).[11][72] The landmark series became a hit that revolutionized the industry with its comparative naturalism and, eventually, a cosmic purview informed by Kirby's seemingly boundless imagination—one well-matched with the consciousness-expanding youth culture of the 1960s.

For almost a decade, Kirby provided Marvel's house style, co-creating with Stan Lee many of the Marvel characters and designing their visual motifs. At Lee's request, he often provided new-to-Marvel artists "breakdown" layouts, over which they would pencil in order to become acquainted with the Marvel look. As artist Gil Kane described:

Jack was the single most influential figure in the turnaround in Marvel's fortunes from the time he rejoined the company ... It wasn't merely that Jack conceived most of the characters that are being done, but ... Jack's point of view and philosophy of drawing became the governing philosophy of the entire publishing company and, beyond the publishing company, of the entire field ... [Marvel took] Jack and use[d] him as a primer. They would get artists ... and they taught them the ABCs, which amounted to learning Jack Kirby. ... Jack was like the Holy Scripture and they simply had to follow him without deviation. That's what was told to me ... It was how they taught everyone to reconcile all those opposing attitudes to one single master point of view.[73]

Highlights of Lee/Kirby collaborations, other than the Fantastic Four, include: the Hulk,[74] Thor,[75] Iron Man, the original X-Men,[76] Doctor Doom, Uatu the Watcher, Magneto, Ego the Living Planet, the Inhumans[77][78] and their hidden city of Attilan, and the Black Panther,[79] comics' first known black superhero—and his African nation of Wakanda.[80] Kirby drew the first Spider-Man story intended for publication in Amazing Fantasy #15 but Stan Lee chose to have Steve Ditko redraw the story.[81]

Lee and Kirby gathered several of their newly created characters together into the team title The Avengers[82] and would revive characters from the 1940s such as the Sub-Mariner,[83] Captain America,[84] and Ka-Zar.[85]

The story frequently cited as Lee and Kirby's finest achievement[86][87] is the three-part "The Galactus Trilogy" that began in Fantastic Four #48 (March 1966), chronicling the arrival of Galactus, a cosmic giant who wanted to devour the planet, and his herald, the Silver Surfer.[88][89] Fantastic Four #48 was chosen as #24 in the 100 Greatest Marvels of All Time poll of Marvel's readers in 2001. Editor Robert Greenberger wrote in his introduction to the story that "As the fourth year of the Fantastic Four came to a close, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby seemed to be only warming up. In retrospect, it was perhaps the most fertile period of any monthly title during the Marvel Age."[90] Comics historian Les Daniels noted that "[t]he mystical and metaphysical elements that took over the saga were perfectly suited to the tastes of young readers in the 1960s", and Lee soon discovered that the story was a favorite on college campuses.[91]

In 1968 and 1969, Joe Simon was involved in litigation with Marvel Comics over the ownership of Captain America, initiated by Marvel after Simon registered the copyright renewal for Captain America in his own name. According to Simon, Kirby agreed to support the company in the litigation and, as part of a deal Kirby made with publisher Martin Goodman, signed over to Marvel any rights he might have had to the character.[92]

Kirby continued to expand the medium's boundaries, devising photo-collage covers and interiors, developing new drawing techniques such as the method for depicting energy fields now known as "Kirby Krackle", and other experiments.[93]

Kirby grew increasingly dissatisfied with working at Marvel. There have been a number of reasons given for this dissatisfaction, including resentment over Stan Lee's increasing media prominence, a lack of full creative control, anger over breaches of perceived promises by publisher Martin Goodman, and frustration over Marvel's failure to credit him specifically for his story plotting and for his character creations and co-creations.[94] He began to both script and draw some secondary features for Marvel, such as "The Inhumans" in Amazing Adventures,[95] as well as horror stories for the anthology title Chamber of Darkness, and received full credit for doing so; but in 1970, Kirby was presented with a contract that included such unfavorable terms as a prohibition against legal retaliation. When Kirby objected, the management refused to negotiate any contract changes.[96] Kirby, although he was earning $35,000 a year freelancing for the company,[97] subsequently left Marvel in 1970 for rival DC Comics, under editorial director Carmine Infantino.[98]

DC Comics and the Fourth World saga (1971–1975)

Kirby spent nearly two years negotiating a deal to move to DC Comics,[99] where in late 1970 he signed a three-year contract with an option for two additional years.[100] He produced a series of interlinked titles under the blanket sobriquet "The Fourth World", which included a trilogy of new titles — New Gods, Mister Miracle, and The Forever People — as well as the extant Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen.[11][98][101] Kirby picked the latter book because the series was without a stable creative team and he did not want to cost anyone a job.[102][103] The central villain of the Fourth World series, Darkseid, and some of the Fourth World concepts, appeared in Jimmy Olsen before the launch of the other Fourth World books, giving the new titles greater exposure to potential buyers. The Superman figures and Jimmy Olsen faces drawn by Kirby were redrawn by Al Plastino, and later by Murphy Anderson.[104][105] Les Daniels observed in 1995 that "Kirby's mix of slang and myth, science fiction and the Bible, made for a heady brew, but the scope of his vision has endured."[106] In 2007, comics writer Grant Morrison commented that "Kirby's dramas were staged across Jungian vistas of raw symbol and storm...The Fourth World saga crackles with the voltage of Jack Kirby's boundless imagination let loose onto paper."[107]

An attempt at creating new formats for comics produced the one-shot black-and-white magazines Spirit World and In the Days of the Mob in 1971.[108]

Kirby later produced other DC series such as OMAC,[109] Kamandi,[110] The Demon,[111] and Kobra,[112] and worked on such extant features as "The Losers" in Our Fighting Forces.[113] Together with former partner Joe Simon for one last time, he worked on a new incarnation of the Sandman.[11][114] Kirby produced three issues of the 1st Issue Special anthology series and created Atlas The Great,[115] a new Manhunter,[116] and the Dingbats of Danger Street.[117]

Kirby's production assistant of the time, Mark Evanier, recounted that DC's policies of the era were not in synch with Kirby's creative impulses, and that he was often forced to work on characters and projects on which he did not want to work.[105]

Return to Marvel (1976–1978)

At the comic book convention Marvelcon '75, in spring 1975, Stan Lee used a Fantastic Four panel discussion to announce that Kirby was returning to Marvel after having left in 1970 to work for DC Comics. Lee wrote in his monthly column, "Stan Lee's Soapbox", that, "I mentioned that I had a special announcement to make. As I started telling about Jack's return, to a totally incredulous audience, everyone's head started to snap around as Kirby himself came waltzin' down the aisle to join us on the rostrum! You can imagine how it felt clownin' around with the co-creator of most of Marvel's greatest strips once more."[118]

Back at Marvel, Kirby both wrote and drew the monthly Captain America series[119] as well as the Captain America's Bicentennial Battles one-shot in the oversized treasury format.[120] He created the series The Eternals,[121] which featured a race of inscrutable alien giants, the Celestials, whose behind-the-scenes intervention in primordial humanity would eventually become a core element of Marvel Universe continuity. He produced an adaptation and expansion of the film 2001: A Space Odyssey,[122] as well as an abortive attempt to do the same for the classic television series, The Prisoner.[123] He wrote and drew Black Panther and drew numerous covers across the line.[11]

Kirby's other Marvel creations in this period include Machine Man[124] and Devil Dinosaur.[125] Kirby's final comics collaboration with Stan Lee, The Silver Surfer: The Ultimate Cosmic Experience, was published in 1978 as part of the Marvel Fireside Books series and is considered to be Marvel's first graphic novel.[126]

Film and animation (1979–1980)

Still dissatisfied with Marvel's treatment of him,[127] and with an offer of employment from Hanna-Barbera,[128] Kirby left Marvel to work in animation. In that field, he did designs for Turbo Teen, Thundarr the Barbarian and other animated series for television.[105] He worked on The New Fantastic Four animated series, reuniting him with scriptwriter Stan Lee.[129] He illustrated an adaptation of the Walt Disney movie The Black Hole for Walt Disney’s Treasury of Classic Tales syndicated comic strip in 1979-80.[130]

In 1979, Kirby drew concept art for film producer Barry Geller's script treatment adapting Roger Zelazny's science fiction novel, Lord of Light, for which Geller had purchased the rights. In collaboration, Geller commissioned Kirby to draw set designs that would be used as architectural renderings for a Colorado theme park to be called Science Fiction Land; Geller announced his plans at a November press conference attended by Kirby, former NFL American football star Rosey Grier, writer Ray Bradbury, and others. While the film did not come to fruition, Kirby's drawings were used for the CIA's "Canadian caper", in which some members of the U.S. embassy in Tehran, Iran, who had avoided capture in the Iran hostage crisis, were able to escape the country posing as members of a movie location-scouting crew.[131]

Final years and death (1981–1994)

In the early 1980s, Pacific Comics, a new, non-newsstand comic book publisher, made a then-groundbreaking deal with Kirby to publish a creator-owned series, Captain Victory and the Galactic Rangers,[132][133] and the six-issue miniseries Silver Star, which was collected in hardcover format in 2007.[134][135][136] This, together with similar actions by other independent comics publishers as Eclipse Comics (where Kirby co-created Destroyer Duck in a benefit comic-book series published to help Steve Gerber fight a legal case versus Marvel),[137] helped establish a precedent to end the monopoly of the work for hire system, wherein comics creators, even freelancers, had owned no rights to characters they created.

Kirby continued to do periodic work for DC Comics during the 1980s, including a brief revival of his "Fourth World" saga in the 1984 and 1985 Super Powers miniseries[138] and the 1985 graphic novel The Hunger Dogs. DC executives Jenette Kahn and Paul Levitz had Kirby re-design the Fourth World characters for the Super Powers toyline as a way of entitling him to royalties for several of his DC creations.[139]

In 1987, under pressure from comics creators and the fan community, Marvel finally returned approximately 1,900[140] or 2,100 pages[141] of the estimated 10,000[141] to 13,000[142] Kirby drew for the company.[141][142]

In 1985, Kirby helped to create the concept and designs for The Centurions, along with Gil Kane. A comic book series based on the show was published by DC and a toyline was produced by Kenner.

Kirby retained ownership of characters used by Topps Comics beginning in 1993, for a set of series in what the company dubbed "The Kirbyverse".[143] These titles were derived mainly from designs and concepts that Kirby had kept in his files, some intended initially for the by-then-defunct Pacific Comics, and then licensed to Topps for what would become the "Jack Kirby's Secret City Saga" mythos.[144]

Phantom Force was the last comic book which Jack Kirby worked on before his death. The story was co-written by Kirby with Michael Thibodeaux and Richard French, based on an eight-page pitch for an unused Bruce Lee comic in 1978.[145] Issues #1 and 2 were published by Image Comics with various Image artists inking over Kirby's pencils. Issue #0 and issues #3 to 8 were published by Genesis West with Kirby providing pencils for issues #0 and 4. Thibodeaux provided the art for the remaining issues of the series after Kirby died.

Marvel posthumously published a "lost" Kirby/Lee Fantastic Four story, Fantastic Four: The Lost Adventure (April 2008), with unused pages Kirby had originally drawn for a story that was partially published in Fantastic Four #108 (March 1971).[146][147]

Politically, he was a liberal Democrat.[148]

On February 6, 1994, Kirby died at age 76 of heart failure in his Thousand Oaks, California home.[149] He was buried at the Pierce Brothers Valley Oaks Memorial Park, Westlake Village, California.[150] Politically, he was a liberal Democrat.[151]

Kirby's estate

Subsequent releases

Lisa Kirby announced in early 2006 that she and co-writer Steve Robertson, with artist Mike Thibodeaux, planned to publish via the Marvel Comics Icon imprint a six-issue limited series, Jack Kirby’s Galactic Bounty Hunters, featuring characters and concepts created by her father for Captain Victory.[34] The series, scripted by Lisa Kirby, Robertson, Thibodeaux, and Richard French, with pencil art by Jack Kirby and Thibodeaux, and inking by Scott Hanna and Karl Kesel primarily, ran an initial five issues (Sept. 2006–Jan. 2007) and then a later final issue (Sept. 2007).[152]

In 2011, Dynamite Entertainment published Kirby: Genesis, an eight-issue miniseries by writer Kurt Busiek and artists Jack Herbert and Alex Ross, featuring Kirby-owned characters previously published by Pacific Comics and Topps Comics.[153][154]

Copyright dispute

On September 16, 2009,[155] Kirby's four children served notices of termination to The Walt Disney Studios, 20th Century Fox, Universal Pictures, Paramount Pictures, and Sony Pictures to attempt to gain control of various Silver Age Marvel characters.[156][157] Marvel sought to invalidate those claims.[158][159] In mid-March 2010 Kirby's children "sued Marvel to terminate copyrights and gain profits from [Kirby's] comic creations."[160] In July 2011, the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York issued a summary judgment in favor of Marvel,[155][161] which was affirmed in August 2013 by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.[162] The Kirby children filed a petition on March 21, 2014, for a review of the case by the Supreme Court of the United States,[163][164] but a settlement was reached on September 26, 2014, and the family requested that the petition be dismissed.[165] While the settlement has left uncertainty in the jurisprudence relating to works governed by the Copyright Act of 1909 that were created before the Copyright Act of 1976 came into force, the Kirby children's attorney, Marc Toberoff, said the issue of creators' rights to reclaim the work done as independent contractors remains, and other potential claims have yet to become ripe.[166]

Legacy

The New York Times, in a Sunday op-ed piece written more than a decade after his death, said of Kirby:

He created a new grammar of storytelling and a cinematic style of motion. Once-wooden characters cascaded from one frame to another—or even from page to page—threatening to fall right out of the book into the reader's lap. The force of punches thrown was visibly and explosively evident. Even at rest, a Kirby character pulsed with tension and energy in a way that makes movie versions of the same characters seem static by comparison.[167]

Michael Chabon, in his afterword to his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, a fictional account of two early comics pioneers, wrote, "I want to acknowledge the deep debt I owe in this and everything else I've ever written to the work of the late Jack Kirby, the King of Comics."[168] Director James Cameron said Kirby inspired the look of his film Aliens, calling it "not intentional in the sense I sat down and looked at all my favorite comics and studied them for this film, but, yeah, Kirby's work was definitely in my subconscious programming. The guy was a visionary. Absolutely. And he could draw machines like nobody's business. He was sort of like A. E. van Vogt and some of these other science-fiction writers who are able to create worlds that — even though we live in a science-fictionary world today — are still so far beyond what we're experiencing."[169]

Several Kirby images are among those on the "Marvel Super Heroes" set of commemorative stamps issued by the U.S. Postal Service on July 27, 2007.[170] Ten of the stamps are portraits of individual Marvel characters and the other 10 stamps depict individual Marvel Comic book covers. According to the credits printed on the back of the pane, Kirby's artwork is featured on: Captain America, The Thing, Silver Surfer, The Amazing Spider-Man #1, The Incredible Hulk #1, Captain America #100, The X-Men #1, and The Fantastic Four #3.[167][170]

In 2002, jazz percussionist Gregg Bendian released a seven-track CD, Requiem for Jack Kirby, inspired by Kirby's art and storytelling. Titles of the instrumental cuts include "Kirby's Fourth World", "New Gods", "The Mother Box", "Teaneck in the Marvel Age" and "Air Above Zenn-La".[171]

Various comic-book and cartoon creators have done homages to Kirby. Examples include the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Mirage Comics series ("Kirby and the Warp Crystal" in Donatello #1, and its animated counterpart, "The King", from the 2003 cartoon series). The episode of Superman: The Animated Series entitled "Apokolips...Now!, Part 2" was dedicated to his memory.[172][173]

As of September 2012, Hollywood films based on characters Kirby co-created have collectively earned nearly $3.1 billion.[174] Kirby himself is a character portrayed by Luis Yagüe in the 2009 Spanish short film The King & the Worst, which is inspired by Kirby's service in World War II.[175] He is portrayed by Michael Parks in a brief appearance in the fact-based drama Argo (2012), about the Canadian Caper.[176]

A play based on Kirby's life, King Kirby, by New York Innovative Theatre Awards-winner Crystal Skillman and New York Times bestselling comics writer Fred Van Lente, was staged at Brooklyn's Brick Theater as part of its annual Comic Book Theater Festival. The play was a New York Times Critics' Pick selection and was funded by a widely publicized Kickstarter campaign.[177][178][179]

A song titled "Jack Kirby" appears on the album Kaboom by rappers Illus and DJ Johnny.[180]

In the 1990s Superman: The Animated Series television show, police detective Dan Turpin was modeled on Kirby.[181]

The 2016 novel I Hate the Internet frequently mentions Kirby as a "central personage" of the novel.[182]

Awards and honors

Jack Kirby received a great deal of recognition over the course of his career, including the 1967 Alley Award for Best Pencil Artist.[183] The following year he was runner-up behind Jim Steranko. His other Alley Awards were:

- 1963: Favorite Short Story - "The Human Torch Meets Captain America", by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, Strange Tales #114[184]

- 1964:[185]

- Best Novel - "Captain America Joins the Avengers", by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, from The Avengers #4

- Best New Strip or Book - "Captain America", by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, in Tales of Suspense

- 1965: Best Short Story - "The Origin of the Red Skull", by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, Tales of Suspense #66[186]

- 1966: Best Professional Work, Regular Short Feature - "Tales of Asgard" by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, in Thor[187]

- 1967: Best Professional Work, Regular Short Feature - (tie) "Tales of Asgard" and "Tales of the Inhumans", both by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, in Thor[183]

- 1968:[188]

- Best Professional Work, Best Regular Short Feature - "Tales of the Inhumans", by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, in Thor

- Best Professional Work, Hall of Fame - Fantastic Four, by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby; Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., by Jim Steranko[188]

Kirby won a Shazam Award for Special Achievement by an Individual in 1971 for his "Fourth World" series in Forever People, New Gods, Mister Miracle, and Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen.[189] He received an Inkpot Award in 1974[190] and was inducted into the Shazam Awards Hall of Fame in 1975.[191] In 1987 he was an inaugural inductee into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame.[192] He received the 1993 Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award at that year's Eisner Awards.[193]

His work was honored posthumously in 1998: The collection of his New Gods material, Jack Kirby's New Gods, edited by Bob Kahan, won both the Harvey Award for Best Domestic Reprint Project,[194] and the Eisner Award for Best Archival Collection/Project.[195] On July 14, 2017, Jack Kirby was named a Disney Legend for the co-creation of numerous characters that would comprise Disney's Marvel Cinematic Universe.[196]

The Jack Kirby Awards and Jack Kirby Hall of Fame were named in his honor.

With Will Eisner, Robert Crumb, Harvey Kurtzman, Gary Panter and Chris Ware, Kirby was among the artists honored in the exhibition "Masters of American Comics" at the Jewish Museum in New York City from September 16, 2006 to January 28, 2007.[197][198]

Bibliography

References

- ↑ Jack Kirby at the Social Security Death Index via FamilySearch. Retrieved on February 15, 2013.

- ↑ Morrison, Grant (July 23, 2011). "My Supergods from the Age of the Superhero". The Guardian. London, United Kingdom. Archived from the original on November 7, 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- 1 2 Evanier, Mark; Sherman, Steve; et al. "Jack Kirby Biography". Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center. Archived from the original on September 17, 2013. Retrieved 2012-02-24.

- ↑ Hamilton, Sue L. Jack Kirby. ABDO Group, 2006. ISBN 978-1-59928-298-5, p. 4

- ↑ Jones, Gerard (2004). Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book. Basic Books. pp. 195–96. ISBN 978-0-465-03657-8.

- 1 2 Mark Evanier, Mark (2008). Kirby: King of Comics. New York, New York: Abrams. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8109-9447-8.

- ↑ Jones, p. 196

- ↑ "'I've Never Done Anything Halfheartedly'". The Comics Journal. Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books (134). February 1990. Reprinted in George, Milo, ed. (2002). The Comics Journal Library, Volume One: Jack Kirby. Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-56097-466-6.

- ↑ Interview, The Comics Journal #134, reprinted in George, p. 24

- ↑ Interview, The Nostalgia Journal #30, November 1976, reprinted in George, p. 3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Jack Kirby at the Grand Comics Database

- ↑ Jones, p. 197

- ↑ Ro, Ronin (2004). Tales to Astonish: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee and the American Comic Book Revolution. Bloomsbury USA. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-58234-345-7.

- ↑ Ro, p. 16

- ↑ "More Than Your Average Joe - Excerpts from Joe Simon's panels at the 1998 San Diego Comic-Con International". The Jack Kirby Collector. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing (25). August 1999. Archived from the original on November 14, 2010.

- ↑ Sanderson, Peter; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2008). "1940s". Marvel Chronicle A Year by Year History. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 18. ISBN 978-0756641238.

Simon and Kirby decided to create another hero who was their response to totalitarian tyranny abroad.

- 1 2 Ro, p. 25

- ↑ Markstein, Don (2010). "Captain America". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

Captain America was the first successful character published by the company that would become Marvel Comics to debut in his own comic. Captain America Comics #1 was dated March, 1941.

- ↑ Jones, p. 200

- ↑ Ro, p. 21

- ↑ Ro, p. 25-26

- 1 2 Ro, p. 27

- ↑ Ro, p. 28

- ↑ Ro, p. 30

- ↑ Wallace, Daniel; Dolan, Hannah, ed. (2010). "1940s". DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.

Hot properties Joe Simon and Jack Kirby joined DC...[and] after taking over the Sandman and Sandy, the Golden Boy feature in Adventure Comics #72, the writer and artist team turned their attentions to Manhunter with issue #73.

- ↑ Wallace "1940s" in Dolan, p. 41 "The inaugural issue of Boy Commandos represented Joe Simon and Jack Kirby's first original title since they started at DC (though the characters had debuted earlier that year in Detective Comics #64.)"

- 1 2 Ro, p. 32

- ↑ Wallace "1940s" in Dolan, p. 41 "Joe Simon and Jack Kirby took their talents to a second title with Star-Spangled Comics, tackling both the Guardian and the Newsboy Legion in issue #7."

- ↑ Levitz, Paul (2010). "The Golden Age 1938–1956". 75 Years of DC Comics The Art of Modern Mythmaking. Cologne, Germany: Taschen. p. 131. ISBN 9783836519816.

- ↑ Evanier, King of Comics, p. 57

- 1 2 Morrow, John (April 1996). "Roz Kirby Interview Excerpts". The Jack Kirby Collector. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing (10). Archived from the original on November 3, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Ro, p. 46

- ↑ Theakston, Greg (1991). The Jack Kirby Treasury Volume Two. Forestville, California: Eclipse Books. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-56060-134-0.

- 1 2 Brady, Matt (April 20, 2006). "Lisa Kirby, Mike Thibodeaux, & Tom Brevoort on Galactic Bounty Hunters". Newsarama. Archived from the original on September 15, 2009.

- 1 2 Ro, p. 33

- 1 2 Evanier, p. 67

- ↑ Ro, p. 35

- ↑ Ro, p. 40

- ↑ World War II V-mail letter from Kirby to Rosalind, in George, p. 117

- ↑ Ro, p. 40-41

- ↑ Evanier, p. 69

- ↑ Ro, p. 42

- ↑ Ro, p. 45

- 1 2 Simon, Joe, with Jim Simon. The Comic Book Makers (Crestwood/II, 1990) ISBN 978-1-887591-35-5; reissued (Vanguard Productions, 2003) ISBN 978-1-887591-35-5, pp. 123-125

- ↑ Evanier, King of Comics. p. 72

- 1 2 Howell, Richard (1988). "Introduction". Real Love: The Best of the Simon and Kirby Love Comics, 1940s-1950s. Forestville, California: Eclipse Books. ISBN 978-0913035634.

- ↑ Simon, p. 125

- ↑ Kirby, Neal (April 9, 2012). "Growing Up Kirby: The Marvel memories of Jack Kirby's son". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 27, 2013. Retrieved 2012-12-28.

- ↑ Ro, p. 52

- 1 2 Ro, p. 54

- ↑ Beerbohm, Robert Lee (August 1999). "The Mainline Story". The Jack Kirby Collector. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing (25). Archived from the original on April 11, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ↑ Theakston, Greg (1997). The Complete Jack Kirby. Pure Imagination Publishing, Inc. p. 29. ISBN 1-56685-006-1.

- ↑ Simon, Joe; with Simon, Jim (1990). The Comic Book Makers. Crestwood/II Publications. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-887591-35-5. Reissued (Vanguard Productions, 2003) ISBN 978-1-887591-35-5. Page numbers refer to 1990 edition.

- ↑ Mainline at the Grand Comics Database

- ↑ Ro, p. 55

- ↑ Ro, p. 56

- ↑ "'I Created an Army of Characters, and Now My Connection with Them Is Lost". Evanston, Illinois: interview, The Great Electric Bird radio show, WNUR-FM, Northwestern University. May 14, 1971. Transcribed in The Nostalgia Journal (27) August 1976. Reprinted in George, p. 16

- ↑ Ro, p. 60

- ↑ Kirby's 1956-57 Atlas work appeared in nine issues, plus three more published later after being held in inventory, per "Another Pre-Implosion Atlas Kirby". Jack Kirby Museum. November 3, 2007. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. In roughly chronological order: Battleground #14 (Nov. 1956; 5 pp.), Astonishing #56 (Dec. 1956; 4 pp.), Strange Tales of the Unusual #7 (Dec. 1956; 4 pp.), Quick-Trigger Western #16 (Feb. 1957; 5 pp.), Yellow Claw #2-4 (Dec. 1956 - April 1957; 19 pp. each), Black Rider Rides Again #1, a.k.a. Black Rider vol. 2, #1 (Sept. 1957; 19 pp.), and Two Gun Western #12 (Sept. 1957; 5 pp.), plus the inventoried Gunsmoke Western #47 (July 1958; 4 pp.) and #51 (March 1959; 5 pp. plus cover) and Kid Colt Outlaw #86 (Sept. 1959; 5 pp.)

- ↑ Irvine, Alex "1950s" in Dolan, p. 84: "Kirby's first solo project was a test run of a non-super hero adventure team called Challengers of the Unknown. Appearing for the first time in Showcase #6, the team would make a few more Showcase appearances before springing into their own title in May 1958."

- ↑ Evanier, Mark (2001). "Introduction". The Green Arrow. New York, New York: DC Comics.

All were inked by Jack with the aid of his dear spouse, Rosalind. She would trace his pencil work with a static pen line; he would then take a brush, put in all the shadows and bold areas and, where necessary, heavy-up the lines she'd laid down. (Jack hated inking and only did it because he needed the money. After departing DC this time, he almost never inked his own work again.)

- ↑ Ro, p. 61

- ↑ Evanier, King of Comics, pp. 103-106: "The artwork was exquisite, in no small part because Dave Wood had the idea to hire Wally Wood (no relation) to handle the inking."

- ↑ Evanier, King of Comics, p. 109

- ↑ Ro, p. 91

- ↑ Van Lente, Fred; Dunlavey, Ryan (2012). Comic Book History of Comics. San Diego, California: IDW Publishing. p. 100. ISBN 978-1613771976.

- ↑ Jones, p. 282

- ↑ Christiansen, Jeff (March 10, 2011). "Groot". Appendix to the Handbook of the Marvel Universe. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013.

- ↑ Christiansen, Jeff (January 17, 2007). "Grottu". Appendix to the Handbook of the Marvel Universe. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013.

- ↑ Markstein, Don (2009). "The Fly". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014.

- ↑ Markstein, Don (2007). "The Shield". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014.

- ↑ DeFalco, Tom "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 84: "It did not take long for editor Stan Lee to realize that The Fantastic Four was a hit...the flurry of fan letters all pointed to the FF's explosive popularity."

- ↑ Gil Kane, speaking at a forum on July 6, 1985, at the Dallas Fantasy Fair. As quoted in George, p. 109

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 85: "Based on their collaboration on The Fantastic Four, [Stan] Lee worked with Jack Kirby. Instead of a team that fought traditional Marvel monsters however, Lee decided that this time he wanted to feature a monster as the hero."

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 88: "[Stan Lee] had always been fascinated by the legends of the Norse gods and realized that he could use those tales as the basis for his new series centered on the mighty Thor...The heroic and glamorous style that...Jack Kirby [had] was perfect for Thor."

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 94: "The X-Men #1 introduced the world to Professor Charles Xavier and his teenage students Cyclops, Beast, Angel, Iceman, and Marvel Girl. Magneto, the master of magnetism and future leader of the evil mutants, also appeared."

- ↑ Cronin, Brian (September 18, 2010). "A Year of Cool Comics – Day 261". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 111: "The Inhumans, a lost race that diverged from humankind 25,000 years ago and became genetically enhanced."

- ↑ Cronin, Brian (September 19, 2010). "A Year of Cool Comics – Day 262". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 117: Stan Lee wanted to do his part by creating the first black super hero. Lee discussed his ideas with Jack Kirby and the result was seen in Fantastic Four #52.

- ↑ Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 15. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Kirby had the honor of being the first ever penciler to take a swing at drawing Spider-Man. Though his illustrations for the pages of Amazing Fantasy #15 were eventually redrawn by Steve Ditko after Stan Lee decided that Kirby's Spidey wasn't quite youthful enough, the King nevertheless contributed the issue's historic cover.

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 94: "Filled with some wonderful visual action, The Avengers #1 has a very simple story: the Norse god Loki tricked the Hulk into going on a rampage ... The heroes eventually learned about Loki's involvement and united with the Hulk to form the Avengers."

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 86: "Stan Lee and Jack Kirby reintroduced one of Marvel's most popular Golden Age heroes – Namor, the Sub-Mariner."

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 99: "'Captain America lives again!' announced the cover of The Avengers #4...Cap was back."

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 107: "Originally created for pulp magazines, and then used in Marvel Comics #1 (Oct. 1939), Ka-Zar the Great was brought up by tigers...When Stan Lee and Jack Kirby revived the character, they also paid homage to...[Edgar Rice] Burroughs' ideas: The dinosaur-filled Savage Land is based on Burroughs' Savage Pellucidar."

- ↑ Hatfield, Charles (2004). "The Galactus Trilogy: An Appreciation". The Collected Jack Kirby Collector Volume 1. p. 211. ISBN 978-1893905009.

- ↑ Thomas, Roy; Sanderson, Peter (2007). The Marvel Vault: A Museum-in-a-Book with Rare Collectibles from the World of Marvel. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Running Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0762428441.

Then came the issues of all issues, the instant legend, the trilogy of Fantastic Four (#48-50) that excited readers immediately christened 'the Galactus Trilogy', a designation still widely recognized four decades later.

- ↑ Cronin, Brian (February 19, 2010). "A Year of Cool Comics – Day 50". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 115: "Stan Lee may have started the creative discussion that culminated in Galactus, but the inclusion of the Silver Surfer in Fantastic Four #48 was pure Jack Kirby. Kirby realized that a being like Galactus required an equally impressive herald."

- ↑ Greenberger, Robert, ed. (December 2001). 100 Greatest Marvels of All Time. Marvel Comics. p. 26.

- ↑ Daniels, Les (1991). Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics. New York, New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 128. ISBN 9780810938212.

- ↑ Simon, p. 205

- ↑ Foley, Shane (November 2001). "Kracklin' Kirby: Tracing the advent of Kirby Krackle". The Jack Kirby Collector (33). Archived from the original on November 14, 2010.

- ↑ Evanier, King of Comics, p. 126-163

- ↑ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 146: "As Marvel was expanding its line of comics, the company decided to introduce two new 'split' books...Amazing Adventures and Astonishing Tales. Amazing Adventures contained a series about the genetically enhanced Inhumans and a series about intelligence agent the Black Widow."

- ↑ Evanier, King of Comics, p. 163

- ↑ Braun, Saul (May 2, 1971). "Shazam! Here Comes Captain Relevant". The New York Times Magazine. Abstract accessed on January 18, 2012.

- 1 2 Van Lente and Dunlavey, p. 115

- ↑ Ro, p.139

- ↑ Ro, p. 143

- ↑ McAvennie, Michael "1970s" in Dolan, p. 145 "As the writer, artist, and editor of the Fourth World family of interlocking titles, each of which possessed its own distinct tone and theme, Jack Kirby cemented his legacy as a pioneer of grand-scale storytelling."

- ↑ Evanier, Mark. "Afterword." Jack Kirby's Fourth World Omnibus; Volume 1, New York: DC Comics, 2007.

- ↑ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 141 "Since no ongoing creative team had been slated to Superman's Pal, Jimmy Olsen, "King of Comics" Jack Kirby made the title his DC launch point, and the writer/artist's indelible energy and ideas permeated every panel and word balloon of the comic."

- ↑ Evanier, Mark (August 22, 2003). "Jack Kirby's Superman". POV Online. Archived from the original on April 22, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

Plastino drew new Superman figures and Olsen heads in roughly the same poses and positions, and these were pasted into the artwork.

- 1 2 3 Kraft, David Anthony; Slifer, Roger (April 1983). "Mark Evanier". Comics Interview (2). Fictioneer Books. pp. 23–34.

- ↑ Daniels, Les (1995). "The Fourth World: New Gods on Newsprint". DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World's Favorite Comic Book Heroes. New York, New York: Bulfinch Press. p. 165. ISBN 0821220764.

- ↑ Morrison, Grant (2007). "Introduction". Jack Kirby's Fourth World Omnibus Volume One. New York, New York: DC Comics. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-1401213442.

- ↑ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 147: "Believing that new formats were necessary for the comics medium to continue evolving, Kirby oversaw the production of what was labeled his 'Speak-Out Series' of magazines: Spirit World and In the Days of the Mob...Sadly, these unique magazines never found their desired audience."

- ↑ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 161 "In OMAC's first issue, editor/writer/artist Jack Kirby warned readers of "The World That's Coming!", a future world containing wild concepts that are almost frighteningly real today."

- ↑ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 153 "Kirby had already introduced a similar concept and characters in Alarming Tales #1 (1957)...Coupling the premise with his unpublished "Kamandi of the Caves" newspaper strip, Kirby's Last Boy on Earth roamed a world that had been ravaged by the "Great Disaster" and taken over by talking animals."

- ↑ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 152 "While his "Fourth World" opus was winding down, Jack Kirby was busy conjuring his next creation, which emerged not from the furthest reaches of the galaxy but from the deepest pits of Hell. Etrigan was hardly the usual Kirby protagonist."

- ↑ Kelly, Rob (August 2009). "Kobra". Back Issue!. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing (35): 63.

Maybe that’s because Kobra was the creation of the legendary Jack 'King' Kirby, who wrote and penciled the first issue’s story, 'Fangs of the Kobra!'

- ↑ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 161 "Jack Kirby also took on a group of established DC characters that had nothing to lose. The result was a year-long run of Our Fighting Forces tales that were action-packed, personal, and among the most beloved of World War II comics ever produced."

- ↑ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 158 "The legendary tandem of writer Joe Simon and artist/editor Jack Kirby reunited for a one-shot starring the Sandman...Despite the issue's popularity, it would be Simon and Kirby's last collaboration."

- ↑ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 162: "Debuting with Atlas the Great, writer and artist Jack Kirby didn't shrug at the chance to put his spin on the well-known hero."

- ↑ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 164: "Though 1st Issue Special was primarily DC's forum to introduce new characters and storylines, editor Jack Kirby used the series as an opportunity to revamp the Manhunter, whom he and writer Joe Simon had made famous in the 1940s."

- ↑ Abramowitz, Jack (April 2014). "1st Issue Special It Was No Showcase (But It Was Never Meant To Be)". Back Issue!. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing (71): 40–47.

- ↑ Bullpen Bulletins: "The King is Back! 'Nuff Said!", in Marvel Comics cover-dated October 1975, including Fantastic Four #163

- ↑ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 175: "After an absence of half a decade, Jack Kirby returned to Marvel Comics as writer, penciller, and editor of the series he and Joe Simon created back in 1941."

- ↑ Powers, Tom (December 2012). "Kirby Celebrating America's 200th Birthday: Captain America's Bicentennial Battles". Back Issue!. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing (61): 46–49.

- ↑ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 175: "Jack Kirby's most important creation for Marvel during his return in the 1970s was his epic series The Eternals"

- ↑ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 180: "Marvel published its adaptation of director Stanley Kubrick and writer Arthur C. Clarke's classic science fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey as an oversize Marvel Treasury Special."

- ↑ Hatfield, Charles (July 1996). "Once Upon A Time: Kirby's Prisoner". The Jack Kirby Collector (11). Archived from the original on November 14, 2010.

- ↑ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 185: "In [2001: A Space Odyssey] issue #8, cover dated July 1977, [Jack] Kirby introduced a robot whom he originally dubbed 'Mister Machine.' Marvel's 2001 series eventually came to an end but Kirby's robot protagonist went on to star in his own comic book series as Machine Man."

- ↑ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 185: "Jack Kirby's final major creation for Marvel Comics was perhaps his most unusual hero: an intelligent dinosaur resembling a Tyrannosaurus rex."

- ↑ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 187: "[In 1978], Simon & Schuster's Fireside Books published a paperback book titled The Silver Surfer by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby...This book was later recognized as Marvel's first true graphic novel."

- ↑ "Ploog & Kirby Quit Marvel over Contract Dispute", The Comics Journal #44, January 1979, p. 11.

- ↑ Evanier, King of Comics, p. 189: "In 1978, an idea found him. It was an offer from the Hanna-Barbera cartoon studio in Hollywood."

- ↑ Fischer, Stuart (August 2014). "The Fantastic Four and Other Things: A Television History". Back Issue!. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing (74): 30.

Stan Lee was a consultant to this series, and Jack Kirby played a very important part in this show as an animator and helped design the show.

- ↑ "Jack Kirby". Lambiek Comiclopedia. March 6, 2009. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014.

- ↑ Bearman, Joshuah (April 24, 2007). "How the CIA Used a Fake Sci-Fi Flick to Rescue Americans from Tehran". Wired (15.05). Archived from the original on November 14, 2010.

- ↑ Catron, Michael (July 1981). "Kirby's Newest: Captain Victory". Amazing Heroes. Fantagraphics Books (2): 14.

- ↑ Morrow, John (2004). "The Captain Victory Connection". The Collected Jack Kirby Collector Volume 1. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 105. ISBN 978-1893905009.

- ↑ Larsen, Erik (February 18, 2007). "One Fan's Opinion". (column #73), Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on November 14, 2010.

- ↑ Kean, Benjamin Ong Pang (July 29, 2007). "SDCC '07: Erik Larsen, Eric Stephenson on Image's Kirby Plans". Newsarama. Archived from the original on March 29, 2009.

- ↑ Kean, Benjamin Ong Pang (May 2, 2007). "The Current Image: Erik Larsen on Jack Kirby's Silver Star". Newsarama. Archived from the original on March 29, 2009.

- ↑ Markstein, Don (2006). "Destroyer Duck". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012.

[T]he centerpiece of the issue was Gerber's own Destroyer Duck...himself. The artist who worked with Gerber was the legendary Jack Kirby, who, as co-creator of The Fantastic Four, The Avengers, X-Men and many other cornerstones of Marvel's success, had issues of his own with the company.

- ↑ Manning, Matthew K. "1980s" in Dolan, p. 208: "In association with the toy company Kenner, DC released a line of toys called Super Powers...DC soon debuted a five-issue Super Powers miniseries plotted by comic book legend Jack 'King' Kirby, scripted by Joey Cavalieri, and with pencils by Adrian Gonzales."

- ↑ Cronin, Brian (January 17, 2014). "Comic Book Legends Revealed #454". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on April 9, 2014.

- ↑ Dean, Michael (December 29, 2002). "Kirby and Goliath: The Fight for Jack Kirby’s Marvel Artwork". The Comics Journal. Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-31.

- 1 2 3 Gold, Glen (April 1998). "The Stolen Art". The Jack Kirby Collector (19). Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- 1 2 "Marvel Returns Art to Kirby, Adams". The Comics Journal. Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books (116): 15. July 1987.

- ↑ Evanier, p. 207

- ↑ Jon B., Cooke (2006). "Twilight at Topps". The Collected Jack Kirby Collector Volume 5. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. pp. 149–153. ISBN 978-1-893905-57-3.

- ↑ Morrow, John. "The Collected Jack Kirby Collector, Volume 3". Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing.

- ↑ Schedeen, Jesse (February 13, 2008). "Fantastic Four: The Lost Adventure #1 Review". IGN. Archived from the original on August 2, 2014.

- ↑ Fantastic Four: The Lost Adventure at the Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016.

- ↑ Beard, Jim (August 25, 2015). "Kack Kirby Week: Kirby4Heroes". Marvel Comics. Archived from the original on July 23, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ↑ "Jack Kirby, 76; Created Comic-Book Superheroes". The New York Times. February 8, 1994. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Jack Kirby". Find a Grave. Retrieved February 21, 2009."Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 21, 2008. Retrieved January 12, 2012. .

- ↑ Beard, Jim (August 25, 2015). "Kack Kirby Week: Kirby4Heroes". Marvel Comics. Archived from the original on July 23, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ↑ Jack Kirby's Galactic Bounty Hunters at the Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators

- ↑ Biggers, Cliff (July 2010). "Kirby Genesis: A Testament to the King's Talent". Comic Shop News (1206).

- ↑ "Alex Ross & Kurt Busiek Team For Dynamite's Kirby: Genesis". Dynamite Entertainment press release via Newsarama. July 12, 2010. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011.

- 1 2 Marvel Worldwide, Inc., Marvel Characters, Inc. and MVL Rights, LLC, against Lisa R. Kirby, Barbara J. Kirby, Neal L. Kirby and Susan M. Kirby, 777 F.Supp.2d 720 (S.D.N.Y. 2011).

- ↑ Fritz, Ben (September 21, 2009). "Heirs File Claims to Marvel Heroes". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 24, 2010.

- ↑ Kit, Borys and Matthew Belloni (September 21, 2009). "Kirby Heirs Seeking Bigger Chunk of Marvel Universe". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 1, 2011. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ↑ Melrose, Kevin (January 8, 2010). "Marvel Sues to Invalidate Copyright Claims by Jack Kirby's Heirs". Robot 6. Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on January 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Marvel Sues for Rights to Superheroes". Associated Press via The Hollywood Reporter. January 8, 2010. Archived from the original on November 14, 2010.

- ↑ Gardner, Eriq (December 21, 2010). "It's on! Kirby estate sues Marvel; copyrights to Iron Man, Spider-Man at stake". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 1, 2011. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ↑ Finke, Nikki (July 28, 2011). "Marvel Wins Summary Judgments In Jack Kirby Estate Rights Lawsuits". Deadline.com. Archived from the original on August 1, 2011.

- ↑ Marvel Characters Inc. v. Kirby, 726 F.3d 119 (2d. Cir. 2013).

- ↑ Patten, Dominic (April 2, 2014). "Marvel & Disney Rights Case For Supreme Court To Decide Says Jack Kirby Estate". Deadline.com. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014.

- ↑ "Kirby v. Marvel Characters, Inc.". SCOTUSblog.

- ↑ Patten, Dominic (September 26, 2014). "Marvel & Jack Kirby Heirs Settle Legal Battle Ahead Of Supreme Court Showdown". Deadline.com. Archived from the original on September 26, 2014.

- ↑ Frankel, Alison (September 29, 2014). "Marvel settlement with Kirby leaves freelancers’ rights in doubt". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014.

- 1 2 Staples, Brent (August 26, 2007). "Jack Kirby, a Comic Book Genius, Is Finally Remembered". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 17, 2014.

- ↑ Lalumière, Claude (January 2001). "Where There Is Icing". (book review), JanuaryMagazine.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2010.

- ↑ Lovece, Frank (February 26, 1987). "Aliens Arrives on Video this Week". United Media newspaper syndicate. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- 1 2 ""Postal Service Previews 2007 Commemorative Stamp Program" (October 25, 2006 press release)". USPS.com. October 25, 2006. Archived from the original on May 8, 2009. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ Berkwits, Jeff (January 28, 2002). "Requiem for Jack Kirby: Gregg Bendian sketches memorable musical scenes from Jack Kirby's legendary comic-book images". Science Fiction Weekly (SciFi.com). Archived from the original on February 11, 2003.

- ↑ Eury, Michael (2006). The Krypton Companion. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. pp. 226–227. ISBN 978-1893905610.

- ↑ Fogel, Rich and Timm, Bruce (writers); Riba, Dan (director) (February 14, 1998). "Apokolips...Now!, Part 2". Superman: The Animated Series. Season 2. Episode 39. The WB.

- ↑ "Marvel Comics". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- ↑ "The King & the Worst". YouTube. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. "Toronto #4: And the Winner Is..". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 8, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ↑ Webster, Andy (June 22, 2014). "The Amazing Adventures of Pencil Man". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 28, 2015. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Project of the Day: King Kirby". May 23, 2014. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ↑ "King Kirby: A Play by Crystal Skillman and Fred Van Lente". ISBN 9781499288490.

- ↑ "ILLUS & DJ Johnny Juice - KaBOOM". DJBooth.net. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ↑ Bruce Timm in Khoury, George; Khoury, Pedro III (October 1998). "Bruce Timm Interviewed". Jack Kirby Collector (21). TwoMorrows Publishing. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ↑ Jarett,, Kobek,. I hate the Internet : a useful novel (First edition ed.). Los Angeles CA. ISBN 9780996421805. OCLC 923555197.

- 1 2 "1967 Alley Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ "1963 Alley Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ "1964 Alley Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ "1965 Alley Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 10, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ "1966 Alley Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- 1 2 "1968 Alley Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

Mark Hanerfeld originally listed Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. as the winner, but then discovered he had counted separately votes for "Fantastic Four by Jack Kirby" (42 votes), "Fantastic Four by Stan Lee," and "Fantastic Four by Jack Kirby & Stan Lee," which would have given Fantastic Four a total of more than 45 votes and thus the victory.

- ↑ "1971 Academy of Comic Book Arts Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on June 27, 2008. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Inkpot Award Winners". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012.

- ↑ "1974 Academy of Comic Book Arts Awards". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on June 27, 2008. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Will Eisner Comic Industry Award: Summary of Winners". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ "The Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award". San Diego Comic-Con International. 2014. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- ↑ "1998 Harvey Award Nominees and Winners". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ "1998 Will Eisner Comic Industry Award Nominees". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ McMillan, Graeme (July 16, 2017). "Jack Kirby to Be Named "Disney Legend" at D23 Expo in July". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Exhibitions: Masters of American Comics". The Jewish Museum. Archived from the original on October 3, 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ Kimmelman, Michael (October 13, 2006). "See You in the Funny Papers". (art review), The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 11, 2011..

Further reading

- Evanier, Mark (2008). Kirby: King of Comics. Abrams. ISBN 081099447X.

- Wyman, Ray (1993). The Art of Jack Kirby. Blue Rose Press, Inc. ISBN 0-9634467-1-1.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Jack Kirby |

- The Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center

- Jack Kirby at the Comic Book DB

- Jack Kirby on IMDb

- Jack Kirby at Find a Grave

- Jack Kirby at Mike's Amazing World of Comics

- Evanier, Mark. "The Jack F.A.Q.". News From ME. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014.

- Mitchell, Elvis (August 27, 2003). "Jack Kirby Heroes Thrive in Comic Books and Film". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013.

- Christiansen, Jeff. "Creations of Jack Kirby". Appendix to the Handbook of the Marvel Universe. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013.