King's Chapel

|

King's Chapel | |

|

King's Chapel, 2009 | |

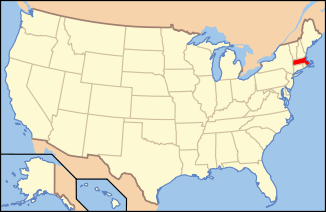

| Location | Tremont and School Streets, Boston, MA |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°21′28.81″N 71°3′35.98″W / 42.3580028°N 71.0599944°WCoordinates: 42°21′28.81″N 71°3′35.98″W / 42.3580028°N 71.0599944°W |

| Built | 1749 |

| Architect | Peter Harrison |

| Architectural style | Georgian |

| NRHP Reference # | 74002045[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 2, 1974 |

| Designated NHL | October 9, 1960 |

King's Chapel is an independent Christian unitarian congregation affiliated with the Unitarian Universalist Association that is "unitarian Christian in theology, Anglican in worship, and congregational in governance."[2] It is housed in what was formerly called "Stone Chapel", an 18th-century structure at the corner of Tremont Street and School Street in Boston, Massachusetts. The chapel building, completed in 1754, is one of the finest designs of the noted colonial architect Peter Harrison, and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960 for its architectural significance.

Despite its name, the adjacent King's Chapel Burying Ground is not affiliated with the chapel or any other church; it pre-dates the chapel by over a century.

History

The King's Chapel congregation was founded by Royal Governor Sir Edmund Andros in 1686 as the first Anglican Church in colonial New England during the reign of King James II. The original King's Chapel was a wooden church built in 1688 at the corner of Tremont and School Streets, where the church stands today. It was situated on the public burying ground, now King's Chapel Burying Ground, because no resident would sell land for a church that was not Congregationalist (at the time, the Congregational church was the official religion of Massachusetts).

In 1749, construction began on the current stone structure, which was designed by Peter Harrison and completed in 1754. The stone church was built around the wooden church. When the stone church was complete, the wooden church was disassembled and removed through the windows of the new church. The wood was then shipped to Lunenburg, Nova Scotia where it was used to construct St. John's Anglican Church. That church was destroyed by fire on Halloween night, 2001. It has since been rebuilt. Originally, there were plans to add a steeple, although funding shortfalls prevented this from happening.[3]

During the American Revolution, the chapel sat vacant and was referred to as the "Stone Chapel." The Loyalist families left for Nova Scotia and England, and those who remained reopened the church in 1782. It became Unitarian under the ministry of James Freeman, who revised the Book of Common Prayer along Unitarian lines in 1785. Although Freeman still considered King's Chapel to be Episcopalian, the Anglican Church refused to ordain him. The church still follows its own Anglican/Unitarian hybrid liturgy today. It is a member congregation of the Unitarian Universalist Association.

Inside, the church is characterized by wooden columns with Corinthian capitals that were hand-carved by William Burbeck and his apprentices in 1758. Seating is accommodated by box pews, most of which were originally owned by the member families who paid pew rent and decorated the pews to their personal tastes. The current uniform appearance of the pews dates from the 1920s.

Music has long been an important part of King's Chapel, which acquired its first organ in 1723. The present organ, the sixth installed in King's Chapel, was built by C.B. Fisk in 1964. It is decorated with miters and carvings from the Bridge organ of 1756, and it is slightly below average in size compared with most mid-1900s European chapel organs.[4] For forty-two years,[5] the eminent American composer Daniel Pinkham was the organist and music director at King's Chapel. He was succeeded by Heinrich Christensen.

The King's Chapel bell, cast in England, was hung in 1772. In 1814 it cracked, was recast by Paul Revere, and was rehung. It is the largest bell cast by the Revere foundry, and the last one cast by Paul Revere himself. It has been rung at services ever since.

Within King's Chapel is a monument to Samuel Vassall, brother of the colonist William Vassall, a patentee of the Massachusetts Bay Company, and an early deputy of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Samuel Vassall of London was also named a member of the Company in its 1629 Royal Charter but never sailed for New England, instead remaining in London to tend to business affairs; his brother William frequently clashed with John Winthrop, and eventually removed himself to Scituate, Massachusetts.[6]

The monument to Samuel Vassall, London merchant, mentions his resistance to King Charles's taxes imposed on Tonnage and Poundage, especially as Parliament had refused the King's request for a lifetime extension. Samuel Vassall subsequently represented London as a Member of Parliament (1640–1641), which restored some of Vassall's estate thought destroyed by the Crown. Ironically, later Vassalls in Massachusetts, including William Vassall for whom Vassalboro, Maine was named, turned Loyalist and fled to England during the American Revolutionary War.[7]

Ministers

- Robert Ratcliff, rector 1686-1689[8]

- Samuel Myles, rector 1689-1728 (d.1728)

- Roger Price, rector 1729-1746

- Henry Caner, rector 1747-1776

- James Freeman, rector 1787-1836 (d.1836)

- Samuel Cary, minister 1809-1815 (d.1815)

- F.W.P. Greenwood, minister 1824-1843 (d.1843)

- Ephraim Peabody, minister 1845-1856 (d.1856)

- no regular minister 1856-1861

- Henry Wilder Foote, minister 1861-1889 (d.1889)

- no regular minister 1889-1895

- Howard Nicholson Brown, minister 1895-1921

- Harold Edwin Balme Speight, minister 1921-1927

- John Carroll Perkins, minister in charge 1927-1931, minister 1931-1933

- Palfrey Perkins, minister 1933-1953

- Joseph Barth, minister 1953-1965 (d. 1988)

- no regular minister 1965-1967

- Carl R. Scovel, senior minister 1967-1999

- Charles C. Forman, affiliate minister 1980-1998 (d. 1998)

- Matthew M. McNaught, interim minister 1999-2001

- Earl K. Holt, minister 2001-2009[9]

- Dianne E. Arakawa, interim minister 2009–2013[10]

- Joy Fallon, minister, 2013-

See also

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Boston

- National Register of Historic Places listings in northern Boston, Massachusetts

| Preceded by Granary Burying Ground |

Locations along Boston's Freedom Trail King's Chapel |

Succeeded by King's Chapel Burying Ground |

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ King's Chapel website

- ↑ "King’s Chapel". Freedom Trail Foundation. 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ Cohen, Paul M. "Survey of Smaller mid-1900s European Chapel Pipe Organs: And The Small-Footed People who Play Them." 2nd edition. London: Palgrave, 1998.

- ↑

- ↑ Apparently even Scituate wasn't far enough away from Winthrop and the Massachusetts authorities to suit Vassall, who departed Scituate after a decade for Barbados, where he died.

- ↑ Annals of King's Chapel from the Puritan Age of New England to the Present Day, Vol. I, Henry Wilder Foote, Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1900

- ↑ Foote. Annals of King's Chapel, v.2. Boston: Little, Brown, 1896; p.602.

- ↑ http://www.kings-chapel.org/documents/Jan08.pdf

- ↑ http://www.kings-chapel.org/MeettheMinisters.html

Further reading

- A History of King's Chapel, in Boston: The First Episcopal Church in New England By Francis William Pitt Greenwood (1833) at Google Books

- Annals of King's Chapel from the Puritan age of New England to the present day. Boston: Little, Brown, 1882, 1896. vol.1; vol.2.

- A Brief Sketch Of The History of King's Chapel (1898) on the Internet Archive

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to King's Chapel. |

- Official website

- The Boston Athenaeum "houses the King’s Chapel Collection of mostly 17th century theological works"

- Boston National Historical Park Official Website