Saudi Arabia

| Kingdom of Saudi Arabia | |

|---|---|

|

Motto: لا إله إلا الله، محمد رسول الله "Lā ʾilāha ʾillāl–lāh, Muhammadun rasūl allāh" "There is no god but God; Muhammad is the messenger of God."[1][lower-alpha 1] (Shahada) | |

.svg.png) | |

| Capital and largest city |

Riyadh 24°39′N 46°46′E / 24.650°N 46.767°E |

| Official languages | Arabic[3] |

| Ethnic groups |

90% Arab 10% Afro-Arab |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

| Demonym |

|

| Government | Unitary Islamic absolute monarchy |

• King | Salman |

| Mohammad | |

| Vacant | |

| Legislature |

None Council of Ministers Consultative Assembly |

| Establishment | |

| 23 September 1932 | |

| 24 October 1945 | |

| 31 January 1992 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,149,690[3] km2 (830,000 sq mi) (12th) |

• Water (%) | 0.7 |

| Population | |

• 2017 estimate | 33,000,000[4] (40th) |

• Density | 15/km2 (38.8/sq mi) (216th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $1.803 trillion[5] (14th) |

• Per capita | $55,229[5] (12th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $689.004 billion[5] (20th) |

• Per capita | $21,100[5] (36th) |

| HDI (2014) |

very high · 39th |

| Currency | Saudi riyal (SR) (SAR) |

| Time zone | AST (UTC+3) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (AH) |

| Drives on the | right |

| Calling code | +966 |

| ISO 3166 code | SA |

| Internet TLD | |

| |

Saudi Arabia[lower-alpha 2] (/ˌsɔːdiː əˈreɪbiə/, /ˌsaʊ-/), officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA),[lower-alpha 3] is an Arab sovereign state in Western Asia constituting the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula. With a land area of approximately 2,150,000 km2 (830,000 sq mi), Saudi Arabia is geographically the fifth-largest state in Asia and second-largest state in the Arab world after Algeria. Saudi Arabia is bordered by Jordan and Iraq to the north, Kuwait to the northeast, Qatar, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates to the east, Oman to the southeast and Yemen to the south. It is separated from Israel and Egypt by the Gulf of Aqaba. It is the only nation with both a Red Sea coast and a Persian Gulf coast and most of its terrain consists of arid desert and mountains.

The area of modern-day Saudi Arabia formerly consisted of four distinct regions: Hejaz, Najd and parts of Eastern Arabia (Al-Ahsa) and Southern Arabia ('Asir).[7] The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was founded in 1932 by Ibn Saud. He united the four regions into a single state through a series of conquests beginning in 1902 with the capture of Riyadh, the ancestral home of his family, the House of Saud. Saudi Arabia has since been an absolute monarchy, effectively a hereditary dictatorship governed along Islamic lines.[8][9] The ultraconservative Wahhabi religious movement within Sunni Islam has been called "the predominant feature of Saudi culture", with its global spread largely financed by the oil and gas trade.[8][9] Saudi Arabia is sometimes called "the Land of the Two Holy Mosques" in reference to Al-Masjid al-Haram (in Mecca) and Al-Masjid an-Nabawi (in Medina), the two holiest places in Islam. The state has a total population of 28.7 million, of which 20 million are Saudi nationals and 8 million are foreigners.[10] The state's official language is Arabic.

Petroleum was discovered on 3 March 1938 and followed up by several other finds in the Eastern Province.[11] Saudi Arabia has since become the world's largest oil producer and exporter, controlling the world's second largest oil reserves and the sixth largest gas reserves.[12] The kingdom is categorized as a World Bank high-income economy with a high Human Development Index[13] and is the only Arab country to be part of the G-20 major economies.[14] However, the economy of Saudi Arabia is the least diversified in the Gulf Cooperation Council, lacking any significant service or production sector (apart from the extraction of resources).[15] The state has attracted criticism for its treatment of women and use of capital punishment.[16] Saudi Arabia is a monarchical autocracy,[17][18] has the fourth highest military expenditure in the world[19][20] and SIPRI found that Saudi Arabia was the world's second largest arms importer in 2010–2014.[21] Saudi Arabia is considered a regional and middle power.[22] In addition to the GCC, it is an active member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and OPEC.[23]

Etymology

Following the unification of the Hejaz and Nejd kingdoms, the new state was named al-Mamlakah al-ʻArabīyah as-Suʻūdīyah (a transliteration of المملكة العربية السعودية in Arabic) by royal decree on 23 September 1932 by its founder, Abdulaziz Al Saud (Ibn Saud). Although this is normally translated as "the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia" in English[24] it literally means "the Saudi Arab kingdom",[25] or "the Arab Saudi Kingdom".[26]

The word "Saudi" is derived from the element as-Suʻūdīyah in the Arabic name of the country, which is a type of adjective known as a nisba, formed from the dynastic name of the Saudi royal family, the Al Saud (آل سعود). Its inclusion expresses the view that the country is the personal possession of the royal family.[27][28] Al Saud is an Arabic name formed by adding the word Al, meaning "family of" or "House of",[29] to the personal name of an ancestor. In the case of the Al Saud, this is the father of the dynasty's 18th century founder, Muhammad bin Saud.[30]

History

There is evidence that human habitation in the Arabian Peninsula dates back to about 125,000 years ago.[31] It is now believed that the first modern humans to spread east across Asia left Africa about 75,000 years ago across the Bab el Mandib connecting Horn of Africa and Arabia.[32]

Before the foundation of Saudi Arabia

In ancient times the Arabian peninsula served as a corridor for trade and exhibited several civilizations. The history before the foundation of Saudi Arabia divided into two phases: pre-Islam and after Islam.

Pre-Islamic Arabia

Religions of the people of the Arabian Peninsula before Islam consisted of indigenous polytheistic beliefs, Arabian Christianity, Nestorian Christianity, Judaism and Zoroastrianism.[33]

Al-Magar Civilization

Al-Magar is prehistoric civilisation that was founded in the center of the Arabian Peninsula, particularly in Najd. Al-Magar is where the first domestication of animals occurred, particularly the horse, during the Neolithic period.[34]

.jpg)

Dilmun Civilization

Dilmun is one of the ancient civilizations in the Middle East and in the Arabian Peninsula.[36][37] It was a major trading centre, and, at the height of its power, controlled the Persian Gulf trading routes.[38][39] The Dilmun encompassed the east large side of the Arabian Peninsula, particularly in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. One of the earliest inscriptions naming Dilmun is that of King Ur-Nanshe of Lagash (c. 2300 BC) discovered in a door-socket: "The ships of Dilmun brought him wood as tribute from foreign lands[40]

Thamud Civilization

Thamud is the name of an ancient civilization in the Hejaz known from the 1st millennium BC to near the time of Muhammad. More than 9,000 Thamudic inscriptions were recorded in south-west Saudi Arabia.[41]

Nabatean Kingdom

The Nabataeans, also Nabateans (/ˌnæbəˈtiːənz/; Arabic: الأنباط al-ʾAnbāṭ , compare to Ancient Greek: Ναβαταίος, Latin: Nabatæus), were an Arab[42] people who inhabited northern Arabia and the Southern Levant, and whose settlements, most prominently the assumed capital city of Raqmu, now called Petra,[42] in CE 37 – c. 100, gave the name of Nabatene to the borderland between Arabia and Syria, from the Euphrates to the Red Sea. Their loosely controlled trading network, which centered on strings of oases that they controlled, where agriculture was intensively practiced in limited areas, and on the routes that linked them, had no securely defined boundaries in the surrounding desert. Trajan conquered the Nabataean kingdom, annexing it to the Roman Empire, where their individual culture, easily identified by their characteristic finely potted painted ceramics, was adopted into the larger Greco-Roman culture. They were later converted to Christianity. Jane Taylor, a writer, describes them as "one of the most gifted peoples of the ancient world".[43]

Kingdom of Lihyan

The kingdom of Lihyan (Arabic: لحيان) or Dedan is an Ancient North Arabian kingdom. It was located in northwestern of the now-day Saudi Arabia, and is known for its Ancient North Arabian inscriptions dating to ca. the 6th to 4th centuries BC.[44]

Kindah Kingdom

Kindah was a tribal kingdom that was established in the Najd in central Arabia. Its kings exercised an influence over a number of associated tribes more by personal prestige than by coercive settled authority. Their first capital was Qaryat Dhāt Kāhil, today known as Qaryat al-Fāw.[45]

Middle Ages and rise of Islam

Shortly before the advent of Islam, apart from urban trading settlements (such as Mecca and Medina), much of what was to become Saudi Arabia was populated by nomadic pastoral tribal societies.[46] The Islamic prophet Muhammad, however, was born in Mecca in about 571 A.D. In the early 7th century, Muhammad united the various tribes of the peninsula and created a single Islamic religious polity.[47] Following his death in 632, his followers rapidly expanded the territory under Muslim rule beyond Arabia, conquering huge and unprecedented swathes of territory (from the Iberian Peninsula in west to modern day Pakistan in east) in a matter of decades. Arabia soon became a more politically peripheral region of the Muslim world as the focus shifted to the vast and newly conquered lands.[47]

Arab dynasties, originating from modern-day Saudi Arabia, Hejaz in particular, founded the Rashidun (632–661), Umayyad (661–750), Abbasid (750–1517) and the Fatimid (909-1171) caliphates.[50][51][52][53][54]

From the 10th century to the early 20th century Mecca and Medina were under the control of a local Arab ruler known as the Sharif of Mecca, but at most times the Sharif owed allegiance to the ruler of one of the major Islamic empires based in Baghdad, Cairo or Istanbul. Most of the remainder of what became Saudi Arabia reverted to traditional tribal rule.[55][56]

For much of the 10th century the Isma'ili-Shi'ite Qarmatians were the most powerful force in the Persian Gulf. In 930, the Qarmatians pillaged Mecca, outraging the Muslim world, particularly with their theft of the Black Stone.[57] In 1077-1078, an Arab Sheikh named Abdullah bin Ali Al Uyuni defeated the Qarmatians in Bahrain and Al-Hasa with the help of the Great Seljuq Empire and founded the Uyunid dynasty.[58][59] The Uyunid Emirate later underwent expansion with its territory stretching from Najd to the Syrian desert.[60] They were overthrown by the Usfurids in 1253.[61] Ufsurid rule was weakened after Persian rulers of Hormuz captured Bahrain and Qatif in 1320.[62] The vassals of Ormuz, the Shia Jarwanid dynasty came to rule eastern Arabia in the 14th century.[63][64] The Jabrids took control of the region after overthrowing the Jarwanids in the 15th century and clashed with Hormuz for more than 2 decades over the region for its economic revenues, until finally agreeing to pay tribute in 1507.[63] Al-Muntafiq tribe later took over the region and came under Ottoman suzerainty. The Bani Khalid tribe later revolted against them in 17th century and took control.[65] Their rule extended from Iraq to Oman at its height and they too came under Ottoman suzerainty.[66][67][68]

Ottoman Hejaz

In the 16th century, the Ottomans added the Red Sea and Persian Gulf coast (the Hejaz, Asir and Al-Ahsa) to the Empire and claimed suzerainty over the interior. One reason was to thwart Portuguese attempts to attack the Red Sea (hence the Hejaz) and the Indian Ocean.[69] Ottoman degree of control over these lands varied over the next four centuries with the fluctuating strength or weakness of the Empire's central authority.[70]

Foundation of the Saud dynasty

The emergence of what was to become the Saudi royal family, known as the Al Saud, began in Nejd in central Arabia in 1744, when Muhammad bin Saud, founder of the dynasty, joined forces with the religious leader Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab,[71] founder of the Wahhabi movement, a strict puritanical form of Sunni Islam.[72] This alliance formed in the 18th century provided the ideological impetus to Saudi expansion and remains the basis of Saudi Arabian dynastic rule today.[73]

The first "Saudi state" established in 1744 in the area around Riyadh, rapidly expanded and briefly controlled most of the present-day territory of Saudi Arabia,[74] but was destroyed by 1818 by the Ottoman viceroy of Egypt, Mohammed Ali Pasha.[75] A much smaller second "Saudi state", located mainly in Nejd, was established in 1824. Throughout the rest of the 19th century, the Al Saud contested control of the interior of what was to become Saudi Arabia with another Arabian ruling family, the Al Rashid. By 1891, the Al Rashid were victorious and the Al Saud were driven into exile in Kuwait.[55]

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Ottoman Empire continued to control or have a suzerainty over most of the peninsula. Subject to this suzerainty, Arabia was ruled by a patchwork of tribal rulers,[76][77] with the Sharif of Mecca having pre-eminence and ruling the Hejaz.[78] In 1902, Abdul Rahman's son, Abdul Aziz—later to be known as Ibn Saud—recaptured control of Riyadh bringing the Al Saud back to Nejd.[55] Ibn Saud gained the support of the Ikhwan, a tribal army inspired by Wahhabism and led by Faisal Al-Dawish, and which had grown quickly after its foundation in 1912.[79] With the aid of the Ikhwan, Ibn Saud captured Al-Ahsa from the Ottomans in 1913.

In 1916, with the encouragement and support of Britain (which was fighting the Ottomans in World War I), the Sharif of Mecca, Hussein bin Ali, led a pan-Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire to create a united Arab state.[80] Although the Arab Revolt of 1916 to 1918 failed in its objective, the Allied victory in World War I resulted in the end of Ottoman suzerainty and control in Arabia.[81]

Ibn Saud avoided involvement in the Arab Revolt, and instead continued his struggle with the Al Rashid. Following the latter's final defeat, he took the title Sultan of Nejd in 1921. With the help of the Ikhwan, the Hejaz was conquered in 1924–25 and on 10 January 1926, Ibn Saud declared himself King of the Hejaz.[82] A year later, he added the title of King of Nejd. For the next five years, he administered the two parts of his dual kingdom as separate units.[55]

After the conquest of the Hejaz, the Ikhwan leadership's objective switched to expansion of the Wahhabist realm into the British protectorates of Transjordan, Iraq and Kuwait, and began raiding those territories. This met with Ibn Saud's opposition, as he recognized the danger of a direct conflict with the British. At the same time, the Ikhwan became disenchanted with Ibn Saud's domestic policies which appeared to favor modernization and the increase in the number of non-Muslim foreigners in the country. As a result, they turned against Ibn Saud and, after a two-year struggle, were defeated in 1929 at the Battle of Sabilla, where their leaders were massacred.[83] In 1932 the two kingdoms of the Hejaz and Nejd were united as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.[55]

Post-unification

The new kingdom was reliant on limited agriculture and pilgrimage revenues.[84] In 1938, vast reserves of oil were discovered in the Al-Ahsa region along the coast of the Persian Gulf, and full-scale development of the oil fields began in 1941 under the US-controlled Aramco (Arabian American Oil Company). Oil provided Saudi Arabia with economic prosperity and substantial political leverage internationally.[55]

Cultural life rapidly developed, primarily in the Hejaz, which was the center for newspapers and radio. However, the large influx of foreign workers in Saudi Arabia in the oil industry increased the pre-existing propensity for xenophobia. At the same time, the government became increasingly wasteful and extravagant. By the 1950s this had led to large governmental deficits and excessive foreign borrowing.[55]

In 1953, Saud of Saudi Arabia succeeded as the king of Saudi Arabia, on his father's death, until 1964 when he was deposed in favor of his half brother Faisal of Saudi Arabia, after an intense rivalry, fueled by doubts in the royal family over Saud's competence. In 1972, Saudi Arabia gained a 20% control in Aramco, thereby decreasing US control over Saudi oil.

In 1973, Saudi Arabia led an oil boycott against the Western countries that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War against Egypt and Syria. Oil prices quadrupled.[55] In 1975, Faisal was assassinated by his nephew, Prince Faisal bin Musaid and was succeeded by his half-brother King Khalid.[85]

By 1976, Saudi Arabia had become the largest oil producer in the world.[86] Khalid's reign saw economic and social development progress at an extremely rapid rate, transforming the infrastructure and educational system of the country;[55] in foreign policy, close ties with the US were developed.[85] In 1979, two events occurred which greatly concerned the government,[87] and had a long-term influence on Saudi foreign and domestic policy. The first was the Iranian Islamic Revolution. It was feared that the country's Shi'ite minority in the Eastern Province (which is also the location of the oil fields) might rebel under the influence of their Iranian co-religionists. There were several anti-government uprisings in the region such as the 1979 Qatif Uprising.[88]

The second event was the Grand Mosque Seizure in Mecca by Islamist extremists. The militants involved were in part angered by what they considered to be the corruption and un-Islamic nature of the Saudi government.[88] The government regained control of the mosque after 10 days and those captured were executed. Part of the response of the royal family was to enforce a much stricter observance of traditional religious and social norms in the country (for example, the closure of cinemas) and to give the Ulema a greater role in government.[89] Neither entirely succeeded as Islamism continued to grow in strength.[90]

In 1980, Saudi Arabia bought out the American interests in Aramco.[91]

King Khalid died of a heart attack in June 1982. He was succeeded by his brother, King Fahd, who added the title "Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques" to his name in 1986 in response to considerable fundamentalist pressure to avoid use of "majesty" in association with anything except God. Fahd continued to develop close relations with the United States and increased the purchase of American and British military equipment.[55]

The vast wealth generated by oil revenues was beginning to have an even greater impact on Saudi society. It led to rapid technological (but not cultural) modernisation, urbanization, mass public education and the creation of new media. This and the presence of increasingly large numbers of foreign workers greatly affected traditional Saudi norms and values. Although there was dramatic change in the social and economic life of the country, political power continued to be monopolized by the royal family[55] leading to discontent among many Saudis who began to look for wider participation in government.[92]

In the 1980s, Saudi Arabia spent $25 billion in support of Saddam Hussein in the Iran–Iraq War.[93] However, Saudi Arabia condemned the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and asked the US to intervene.[55] King Fahd allowed American and coalition troops to be stationed in Saudi Arabia. He invited the Kuwaiti government and many of its citizens to stay in Saudi Arabia, but expelled citizens of Yemen and Jordan because of their governments' support of Iraq. In 1991, Saudi Arabian forces were involved both in bombing raids on Iraq and in the land invasion that helped to liberate Kuwait.

Saudi Arabia's relations with the West began to cause growing concern among some of the ulema and students of sharia law and was one of the issues that led to an increase in Islamist terrorism in Saudi Arabia, as well as Islamist terrorist attacks in Western countries by Saudi nationals. Osama bin Laden was a Saudi national (until stripped of his nationality in 1994) and was responsible for the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings in East Africa and the 2000 USS Cole bombing near the port of Aden, Yemen. 15 of the 19 terrorists involved in September 11 attacks in New York City, Washington, D.C., and near Shanksville, Pennsylvania were Saudi nationals.[94] Many Saudis who did not support the Islamist terrorists were nevertheless deeply unhappy with the government's policies.[95]

Islamism was not the only source of hostility to the government. Although now extremely wealthy, Saudi Arabia's economy was near stagnant. High taxes and a growth in unemployment have contributed to discontent, and has been reflected in a rise in civil unrest, and discontent with the royal family. In response, a number of limited "reforms" were initiated by King Fahd. In March 1992, he introduced the "Basic Law", which emphasised the duties and responsibilities of a ruler. In December 1993, the Consultative Council was inaugurated. It is composed of a chairman and 60 members—all chosen by the King. The King's intent was to respond to dissent while making as few actual changes in the status quo as possible. Fahd made it clear that he did not have democracy in mind: "A system based on elections is not consistent with our Islamic creed, which [approves of] government by consultation [shūrā]."[55]

In 1995, Fahd suffered a debilitating stroke, and the Crown Prince, Abdullah, assumed the role of de facto regent, taking on the day-to-day running of the country. However, his authority was hindered by conflict with Fahd's full brothers (known, with Fahd, as the "Sudairi Seven").[96] From the 1990s, signs of discontent continued and included, in 2003 and 2004, a series of bombings and armed violence in Riyadh, Jeddah, Yanbu and Khobar.[97] In February–April 2005, the first-ever nationwide municipal elections were held in Saudi Arabia. Women were not allowed to take part in the poll.[55]

In 2005, King Fahd died and was succeeded by Abdullah, who continued the policy of minimum reform and clamping down on protests. The king introduced a number of economic reforms aimed at reducing the country's reliance on oil revenue: limited deregulation, encouragement of foreign investment, and privatization. In February 2009, Abdullah announced a series of governmental changes to the judiciary, armed forces, and various ministries to modernize these institutions including the replacement of senior appointees in the judiciary and the Mutaween (religious police) with more moderate individuals and the appointment of the country's first female deputy minister.[55]

On 29 January 2011, hundreds of protesters gathered in the city of Jeddah in a rare display of criticism against the city's poor infrastructure after deadly floods swept through the city, killing eleven people.[98] Police stopped the demonstration after about 15 minutes and arrested 30 to 50 people.[99]

Since 2011, Saudi Arabia has been affected by its own Arab Spring protests.[100] In response, King Abdullah announced on 22 February 2011 a series of benefits for citizens amounting to $36 billion, of which $10.7 billion was earmarked for housing.[101] No political reforms were announced as part of the package, though some prisoners indicted for financial crimes were pardoned.[102] On 18 March the same year, King Abdullah announced a package of $93 billion, which included 500,000 new homes to a cost of $67 billion, in addition to creating 60,000 new security jobs.[103][104]

Although male-only municipal elections were held on 29 September 2011,[105][106] Abdullah allowed women to vote and be elected in the 2015 municipal elections, and also to be nominated to the Shura Council.[107]

Politics

|

|

| Salman Al Saud King and Prime Minister |

Mohammad bin Salman Crown Prince |

Saudi Arabia is an absolute monarchy.[108] However, according to the Basic Law of Saudi Arabia adopted by royal decree in 1992, the king must comply with Sharia (Islamic law) and the Quran, while the Quran and the Sunnah (the traditions of Muhammad) are declared to be the country's constitution.[109] No political parties or national elections are permitted.[108] Critics regard it as a totalitarian dictatorship.[110] The Economist rates the Saudi government as the fifth most authoritarian government out of 167 rated in its 2012 Democracy Index,[18] and Freedom House gives it its lowest "Not Free" rating, 7.0 ("1=best, 7=worst") for 2013.[111]

In the absence of national elections and political parties,[108] politics in Saudi Arabia takes place in two distinct arenas: within the royal family, the Al Saud, and between the royal family and the rest of Saudi society.[112] Outside of the Al-Saud, participation in the political process is limited to a relatively small segment of the population and takes the form of the royal family consulting with the ulema, tribal sheikhs and members of important commercial families on major decisions.[113] This process is not reported by the Saudi media.[114]

By custom, all males of full age have a right to petition the king directly through the traditional tribal meeting known as the majlis.[115] In many ways the approach to government differs little from the traditional system of tribal rule. Tribal identity remains strong and, outside of the royal family, political influence is frequently determined by tribal affiliation, with tribal sheikhs maintaining a considerable degree of influence over local and national events.[113] As mentioned earlier, in recent years there have been limited steps to widen political participation such as the establishment of the Consultative Council in the early 1990s and the National Dialogue Forum in 2003.[116]

The rule of the Al Saud faces political opposition from four sources: Sunni Islamist activism; liberal critics; the Shi'ite minority—particularly in the Eastern Province; and long-standing tribal and regionalist particularistic opponents (for example in the Hejaz).[117] Of these, the Islamic activists have been the most prominent threat to the government and have in recent years perpetrated a number of violent or terrorist acts in the country.[97] However, open protest against the government, even if peaceful, is not tolerated.

Saudi Arabia is the only country in the world that effectively bans women from driving; although there is no written law to that effect, in practice women are hindered from obtaining the locally issued licenses required to drive.[118] On 25 September 2011, Saudi Arabia's King Abdullah announced that women will have the right to stand and vote in future local elections and join the advisory Shura council as full members.[119]

Monarchy and royal family

The king combines legislative, executive, and judicial functions[113] and royal decrees form the basis of the country's legislation.[120] The king is also the prime minister, and presides over the Council of Ministers of Saudi Arabia and Consultative Assembly of Saudi Arabia.

The royal family dominates the political system. The family's vast numbers allow it to control most of the kingdom's important posts and to have an involvement and presence at all levels of government.[121] The number of princes is estimated to be at least 7,000, with most power and influence being wielded by the 200 or so male descendants of Ibn Saud.[122] The key ministries are generally reserved for the royal family,[108] as are the thirteen regional governorships.[123]

Long term political and government appointments have resulted in the creation of "power fiefdoms" for senior princes,[124] such as those of King Abdullah, who had been Commander of the National Guard since 1963 (until 2010, when he appointed his son to replace him),[125] former Crown Prince Sultan, Minister of Defence and Aviation from 1962 to his death in 2011, former crown prince Prince Nayef who was the Minister of Interior from 1975 to his death in 2012, Prince Saud who had been Minister of Foreign Affairs since 1975[126] and current King Salman, who was Minister of Defense and Aviation before he was crown prince and Governor of the Riyadh Province from 1962 to 2011.[127] The current Minister of Defense is Prince Mohammad bin Salman, the son of King Salman and Deputy Crown Prince.[128]

The royal family is politically divided by factions based on clan loyalties, personal ambitions and ideological differences.[112] The most powerful clan faction is known as the 'Sudairi Seven', comprising the late King Fahd and his full brothers and their descendants.[129] Ideological divisions include issues over the speed and direction of reform,[130] and whether the role of the ulema should be increased or reduced. There were divisions within the family over who should succeed to the throne after the accession or earlier death of Prince Sultan.[129][131] When prince Sultan died before ascending to the throne on 21 October 2011, King Abdullah appointed Prince Nayef as crown prince.[132] The following year Prince Nayef also died before ascending to the throne.[133]

The Saudi government and the royal family have often, over many years, been accused of corruption.[134] In a country that is said to "belong" to the royal family and is named for them,[28] the lines between state assets and the personal wealth of senior princes are blurred.[122] The extent of corruption has been described as systemic[135] and endemic,[136] and its existence was acknowledged[137] and defended[138] by Prince Bandar bin Sultan (a senior member of the royal family[139]) in an interview in 2001.[140]

Although corruption allegations have often been limited to broad undocumented accusations,[141] specific allegations were made in 2007, when it was claimed that the British defence contractor BAE Systems had paid Prince Bandar US$2 billion in bribes relating to the Al-Yamamah arms deal.[142] Prince Bandar denied the allegations.[143] Investigations by both US and UK authorities resulted, in 2010, in plea bargain agreements with the company, by which it paid $447 million in fines but did not admit to bribery.[144]

Transparency International in its annual Corruption Perceptions Index for 2010 gave Saudi Arabia a score of 4.7 (on a scale from 0 to 10 where 0 is "highly corrupt" and 10 is "highly clean").[145] Saudi Arabia has undergone a process of political and social reform, such as to increase public transparency and good governance. However, nepotism and patronage are widespread when doing business in the country. The enforcement of the anti-corruption laws is selective and public officials engage in corruption with impunity.

There has been mounting pressure to reform and modernize the royal family's rule, an agenda championed by King Abdullah both before and after his accession in 2005. The creation of the Consultative Council in the early 1990s did not satisfy demands for political participation, and, in 2003, an annual National Dialogue Forum was announced that would allow selected professionals and intellectuals to publicly debate current national issues, within certain prescribed parameters. In 2005, the first municipal elections were held. In 2007, the Allegiance Council was created to regulate the succession.[116] In 2009, the king made significant personnel changes to the government by appointing reformers to key positions and the first woman to a ministerial post.[146] However, the changes have been criticized as being too slow or merely cosmetic.[147]

Al ash-Sheikh and role of the ulema

Saudi Arabia is almost unique in giving the ulema (the body of Islamic religious leaders and jurists) a direct role in government.[148] The preferred ulema are of the Salafi persuasion. The ulema have also been a key influence in major government decisions, for example the imposition of the oil embargo in 1973 and the invitation to foreign troops to Saudi Arabia in 1990.[149] In addition, they have had a major role in the judicial and education systems[150] and a monopoly of authority in the sphere of religious and social morals.[151]

By the 1970s, as a result of oil wealth and the modernization of the country initiated by King Faisal, important changes to Saudi society were under way and the power of the ulema was in decline.[152] However, this changed following the seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1979 by Islamist radicals.[153] The government's response to the crisis included strengthening the ulema's powers and increasing their financial support:[89] in particular, they were given greater control over the education system[153] and allowed to enforce stricter observance of Wahhabi rules of moral and social behaviour.[89] After his accession to the throne in 2005, King Abdullah took steps to reduce the powers of the ulema, for instance transferring control over girls' education to the Ministry of Education.[154]

The ulema have historically been led by the Al ash-Sheikh,[155] the country's leading religious family.[151] The Al ash-Sheikh are the descendants of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, the 18th century founder of the Wahhabi form of Sunni Islam which is today dominant in Saudi Arabia.[156] The family is second in prestige only to the Al Saud (the royal family)[157] with whom they formed a "mutual support pact"[158] and power-sharing arrangement nearly 300 years ago.[149] The pact, which persists to this day,[158] is based on the Al Saud maintaining the Al ash-Sheikh's authority in religious matters and upholding and propagating Wahhabi doctrine. In return, the Al ash-Sheikh support the Al Saud's political authority[159] thereby using its religious-moral authority to legitimize the royal family's rule.[160] Although the Al ash-Sheikh's domination of the ulema has diminished in recent decades,[161] they still hold the most important religious posts and are closely linked to the Al Saud by a high degree of intermarriage.[151]

Legal system

The primary source of law is the Islamic Sharia derived from the teachings of the Qur'an and the Sunnah (the traditions of the Prophet).[120] Saudi Arabia is unique among modern Muslim states in that Sharia is not codified and there is no system of judicial precedent, giving judges the power to use independent legal reasoning to make a decision. Saudi judges tend to follow the principles of the Hanbali school of jurisprudence (or fiqh) found in pre-modern texts[163] and noted for its literalist interpretation of the Qur'an and hadith.[164]

Because the judge is empowered to disregard previous judgments (either his own or of other judges) and may apply his personal interpretation of Sharia to any particular case, divergent judgements arise even in apparently identical cases,[165] making predictability of legal interpretation difficult.[166] The Sharia court system constitutes the basic judiciary of Saudi Arabia and its judges (qadi) and lawyers form part of the ulema, the country's Islamic scholars.

Royal decrees are the other main source of law; but are referred to as regulations rather than laws because they are subordinate to the Sharia.[120] Royal decrees supplement Sharia in areas such as labor, commercial and corporate law. Additionally, traditional tribal law and custom remain significant.[167] Extra-Sharia government tribunals usually handle disputes relating to specific royal decrees.[168] Final appeal from both Sharia courts and government tribunals is to the King and all courts and tribunals follow Sharia rules of evidence and procedure.[169]

The Saudi system of justice has been criticized for its "ultra-puritanical judges", who are often harsh in their sentencing (with beheading for the crime of witchcraft), but also sometimes overly lenient (for cases of rape or wife-beating) and slow, for example leaving thousands of abandoned women unable to secure a divorce.[170][171] The system has also been criticized for being arcane,[172] lacking in some of the safeguards of justice, and unable to deal with the modern world.[173] In 2007, King Abdullah issued royal decrees reforming the judiciary and creating a new court system,[165] and, in 2009, the King made a number of significant changes to the judiciary's personnel at the most senior level by bringing in a younger generation.[172]

Capital and physical punishments imposed by Saudi courts, such as beheading, stoning (to death), amputation, crucifixion and lashing, as well as the sheer number of executions have been strongly criticized.[175] The death penalty can be imposed for a wide range of offences including murder, rape, armed robbery, repeated drug use, apostasy, adultery, witchcraft and sorcery and can be carried out by beheading with a sword, stoning or firing squad, followed by crucifixion.[176][177][178] The 345 reported executions between 2007 and 2010 were all carried out by public beheading. The last reported execution for sorcery took place in September 2014.[179]

Although repeated theft can be punishable by amputation of the right hand, only one instance of judicial amputation was reported between 2007 and 2010. Homosexual acts are punishable by flogging or death.[176][178][180] Atheism or "calling into question the fundamentals of the Islamic religion on which this country is based" is considered a terrorist crime.[181] Lashings are a common form of punishment[182] and are often imposed for offences against religion and public morality such as drinking alcohol and neglect of prayer and fasting obligations.[176]

Retaliatory punishments, or Qisas, are practised: for instance, an eye can be surgically removed at the insistence of a victim who lost his own eye.[171] Families of someone unlawfully killed can choose between demanding the death penalty or granting clemency in return for a payment of diyya (blood money), by the perpetrator.[183]

Human rights

Western-based organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch condemn both the Saudi criminal justice system and its severe punishments. There are no jury trials in Saudi Arabia and courts observe few formalities.[184] Human Rights Watch, in a 2008 report, noted that a criminal procedure code had been introduced for the first time in 2002, but it lacked some basic protections and, in any case, had been routinely ignored by judges. Those arrested are often not informed of the crime of which they are accused or given access to a lawyer and are subject to abusive treatment and torture if they do not confess. At trial, there is a presumption of guilt and the accused is often unable to examine witnesses and evidence or present a legal defense. Most trials are held in secret.[185] An example of sentencing is that UK pensioner and cancer victim Karl Andree, aged 74, faced 360 lashes for home brewing alcohol.[186] He was later released due to intervention by the British government.[187]

Saudi Arabia is widely accused of having one of the worst human rights records in the world. Human rights issues that have attracted strong criticism include the extremely disadvantaged position of women (see Women below), capital punishment for homosexuality,[188] religious discrimination, the lack of religious freedom and the activities of the religious police (see Religion below).[175] Between 1996 and 2000, Saudi Arabia acceded to four UN human rights conventions and, in 2004, the government approved the establishment of the National Society for Human Rights (NSHR), staffed by government employees, to monitor their implementation. To date, the activities of the NSHR have been limited and doubts remain over its neutrality and independence.[189]

Saudi Arabia remains one of the very few countries in the world not to accept the UN's Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In response to the continuing criticism of its human rights record, the Saudi government points to the special Islamic character of the country, and asserts that this justifies a different social and political order.[190] The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom had unsuccessfully[191] urged President Barack Obama to raise human rights concerns with King Abdullah on his March 2014 visit to the Kingdom especially the imprisonments of Sultan Hamid Marzooq al-Enezi, Saud Falih Awad al-Enezi, and Raif Badawi.[192]

Saudi Arabia also conducts about 2 executions per week, mainly for murder and drug smuggling, although there are people who have been executed for deserting Islam and crimes against the Faisal bin Musaid.[193] The method of execution is normally beheading in public.[194] For example, Ali Mohammed Baqir al-Nimr was arrested in 2012 when he was 17 years old for taking part in an anti-government protests in Saudi Arabia during the Arab Spring.[195] In May 2014, Ali al-Nimr was sentenced to be publicly beheaded and crucified.[196]

In 2013, the government deported thousands of non-Saudis, many of them who were working illegally in the country or had overstayed their visas. Many reports abound, of foreigner workers being tortured either by employers or others.[197] This resulted in many basic services suffering from a lack of workers, as many Saudi Arabian citizens are not keen on working in blue collar jobs.[198]

Saudi Arabia has a "Counter-Radicalization Program" the purpose of which is to "combat the spread and appeal of extremist ideologies among the general populous" and to "instill the true values of the Islamic faith, such as tolerance and moderation."[199] This "tolerance and moderation" has been called into question by the Baltimore Sun, based on the reports from Amnesty International regarding Raif Badawi,[200] and in the case of a man from Hafr al-Batin sentenced to death for rejecting Islam.[201] In September 2015, Faisal bin Hassan Trad, Saudi Arabia's ambassador to the UN in Geneva, has been elected Chair of the United Nations Human Rights Council panel that appoints independent experts.[202] In January 2016, Saudi Arabia executed the prominent Shia cleric Sheikh Nimr who had called for pro-democracy demonstrations and for free elections in Saudi Arabia.[203]

Foreign relations

Saudi Arabia joined the UN in 1945[24][204] and is a founding member of the Arab League, Gulf Cooperation Council, Muslim World League, and the Organization of the Islamic Conference (now the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation).[205] It plays a prominent role in the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and in 2005 joined the World Trade Organization.[24] Saudi Arabia supports the intended formation of the Arab Customs Union in 2015 and an Arab common market[206] by 2020, as announced at the 2009 Arab League summit.[207]

Since 1960, as a founding member of OPEC, its oil pricing policy has been generally to stabilize the world oil market and try to moderate sharp price movements so as to not jeopardise the Western economies.[24][208]

Between the mid-1970s and 2002 Saudi Arabia expended over $70 billion in "overseas development aid". However, there is evidence that the vast majority was, in fact, spent on propagating and extending the influence of Wahhabism at the expense of other forms of Islam.[209] There has been an intense debate over whether Saudi aid and Wahhabism has fomented extremism in recipient countries.[210] The two main allegations are that, by its nature, Wahhabism encourages intolerance and promotes terrorism.[211] Counting only the non-Muslim-majority countries, Saudi Arabia has paid for the construction of 1359 mosques, 210 Islamic centres, 202 colleges and 2000 schools.[212]

Saudi Arabia and the United States are strategic allies,[213][214] and since President Barack Obama took office in 2009, the U.S. has sold $110 billion in arms to Saudi Arabia.[215][216] In the first decade of the 21st century the Saudi Arabia paid approximately $100 million to American firms to lobby the U.S. government.[217] The relations with the U.S. became strained following 9/11.[218] American politicians and media accused the Saudi government of supporting terrorism and tolerating a jihadist culture.[219] Indeed, Osama bin Laden and fifteen out of the nineteen 9/11 hijackers were from Saudi Arabia;[220] in ISIL-occupied Raqqa, in mid-2014, all 12 judges were Saudi.[221] According to former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, "Saudi Arabia remains a critical financial support base for al-Qaida, the Taliban, LeT and other terrorist groups... Donors in Saudi Arabia constitute the most significant source of funding to Sunni terrorist groups worldwide."[222] Former CIA director James Woolsey described it as "the soil in which Al-Qaeda and its sister terrorist organizations are flourishing."[223] The Saudi government denies these claims or that it exports religious or cultural extremism.[224] In April 2016, Saudi Arabia has threatened to sell off $750 billion in Treasury securities and other U.S. assets if Congress passes a bill that would allow the Saudi government to be sued over 9/11.[213]

In the Arab and Muslim worlds, Saudi Arabia is considered to be pro-Western and pro-American,[226] and it is certainly a long-term ally of the United States.[227] However, this[228] and Saudi Arabia's role in the 1991 Persian Gulf War, particularly the stationing of U.S. troops on Saudi soil from 1991, prompted the development of a hostile Islamist response internally.[229] As a result, Saudi Arabia has, to some extent, distanced itself from the U.S. and, for example, refused to support or to participate in the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.[113]

The consequences of the 2003 invasion and the Arab Spring led to increasing alarm within the Saudi monarchy over the rise of Iran's influence in the region.[230] These fears were reflected in comments of King Abdullah,[154] who privately urged the United States to attack Iran and "cut off the head of the snake".[231] The tentative rapprochement between the US and Iran that began in secret in 2011[232] was said to be feared by the Saudis,[233] and, during the run up to the widely welcomed deal on Iran's nuclear programme that capped the first stage of US–Iranian détente, Robert Jordan, who was U.S. ambassador to Riyadh from 2001 to 2003, said "[t]he Saudis' worst nightmare would be the [Obama] administration striking a grand bargain with Iran."[234] A trip to Saudi by US President Barack Obama in 2014 included discussions of US–Iran relations, though these failed to resolve Riyadh's concerns.[235]

In order to protect the house of Khalifa, the monarchs of Bahrain, Saudi Arabia invaded Bahrain by sending military troops to quell the uprising of Bahraini people on 14 March 2011.[236] The Saudi government considered the two-month uprising as a "security threat" posed by the Shia who represent the majority of Bahrain population.[236]

.jpg)

According to the Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki in March 2014, Saudi Arabia along with Qatar provided political, financial and media support to terrorists against the Iraqi government.[237]

On 25 March 2015, Saudi Arabia, spearheading a coalition of Sunni Muslim states,[238] started a military intervention in Yemen against the Shia Houthis and forces loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was deposed in the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings.[239]

As of 2015, together with Qatar and Turkey, Saudi Arabia is openly supporting the Army of Conquest,[240] an umbrella group of anti-government forces fighting in the Syrian Civil War that reportedly includes an al-Qaeda linked al-Nusra Front and another Salafi coalition known as Ahrar al-Sham.[241]

Following a number of incidents during the Hajj season, the deadliest[242] of which killed at least 2,070 pilgrim[243] in 2015 Mina stampede, Saudi Arabia has been accused of mismanagement and focusing on increasing money revenues while neglecting pilgrims' welfare.[244]

Saudi Arabia has been seen as a moderating influence in the Arab–Israeli conflict, periodically putting forward a peace plan between Israel and the Palestinians and condemning Hezbollah.[245] Following the Arab Spring Saudi Arabia offered asylum to deposed President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia and King Abdullah telephoned President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt (prior to his deposition) to offer his support.[246] In early 2014 relations with Qatar became strained over its support for the Muslim Brotherhood, and Saudi Arabia's belief that Qatar was interfering in its affairs. In August 2014 both countries appeared to be exploring ways of ending the rift.[247]

Military

Saudi Arabia has one of the highest percentages of military expenditure in the world, spending more than 10% of its GDP in its military. The Saudi military consists of the Royal Saudi Land Forces, the Royal Saudi Air Force, the Royal Saudi Navy, the Royal Saudi Air Defense, the Saudi Arabian National Guard (SANG, an independent military force), and paramilitary forces, totaling nearly 200,000 active-duty personnel. In 2005 the armed forces had the following personnel: the army, 75,000; the air force, 18,000; air defense, 16,000; the navy, 15,500 (including 3,000 marines); and the SANG had 75,000 active soldiers and 25,000 tribal levies. [248] In addition, there is an Al Mukhabarat Al A'amah military intelligence service.

The kingdom has a long-standing military relationship with Pakistan, it has long been speculated that Saudi Arabia secretly funded Pakistan's atomic bomb programme and seeks to purchase atomic weapons from Pakistan, in near future.[249][250] The SANG is not a reserve but a fully operational front-line force, and originated out of Ibn Saud's tribal military-religious force, the Ikhwan. Its modern existence, however, is attributable to it being effectively Abdullah's private army since the 1960s and, unlike the rest of the armed forces, is independent of the Ministry of Defense and Aviation. The SANG has been a counterbalance to the Sudairi faction in the royal family: The late prince Sultan, former Minister of Defense and Aviation, was one of the so-called 'Sudairi Seven' and controlled the remainder of the armed forces until his death in 2011.[251]

.jpg)

Spending on defense and security has increased significantly since the mid-1990s and was about US$25.4 billion in 2005. Saudi Arabia ranks among the top 10 in the world in government spending for its military, representing about 7% of gross domestic product in 2005. Its modern high-technology arsenal makes Saudi Arabia among the world's most densely armed nations, with its military equipment being supplied primarily by the US, France and Britain.[248]

The United States sold more than $80 billion in military hardware between 1951 and 2006 to the Saudi military.[252] On 20 October 2010, the U.S. State Department notified Congress of its intention to make the biggest arms sale in American history—an estimated $60.5 billion purchase by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The package represents a considerable improvement in the offensive capability of the Saudi armed forces.[253] 2013 saw Saudi military spending climb to $67bn, overtaking that of the UK, France and Japan to place fourth globally.[254]

The United Kingdom has also been a major supplier of military equipment to Saudi Arabia since 1965.[255] Since 1985, the UK has supplied military aircraft—notably the Tornado and Eurofighter Typhoon combat aircraft—and other equipment as part of the long-term Al-Yamamah arms deal estimated to have been worth £43 billion by 2006 and thought to be worth a further £40 billion.[256] In May 2012, British defence giant BAE signed a £1.9bn ($3bn) deal to supply Hawk trainer jets to Saudi Arabia.[257]

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, SIPRI, in 2010–14 Saudi Arabia became the world's second largest arms importer, receiving four times more major arms than in 2005–2009. Major imports in 2010–14 included 45 combat aircraft from the UK, 38 combat helicopters from the USA, 4 tanker aircraft from Spain and over 600 armoured vehicles from Canada. Saudi Arabia has a long list of outstanding orders for arms, including 27 more combat aircraft from the UK, 154 combat aircraft from the USA and a large number of armoured vehicles from Canada.[21] Saudi Arabia received 41 per cent of UK arms exports in 2010–14.[258] France authorized $18 billion in weapons sales to Saudi Arabia in 2015 alone.[216] The $15 billion arms deal with Saudi Arabia is believed to be the largest arms sale in Canadian history.[259] In 2016, the European Parliament decided to temporarily impose an arms embargo against Saudi Arabia, as a result of the Yemen civilian population's suffering from the conflict with Saudi Arabia.[260] In 2017, Saudi Arabia signed a 110 billion dollar arms deal with the United States.

Geography

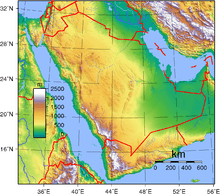

Saudi Arabia occupies about 80% of the Arabian Peninsula (the world's largest peninsula),[262] lying between latitudes 16° and 33° N, and longitudes 34° and 56° E. Because the country's southern borders with the United Arab Emirates and Oman are not precisely marked, the exact size of the country is undefined.[262] The CIA World Factbook estimates 2,149,690 km2 (830,000 sq mi) and lists Saudi Arabia as the world's 13th largest state.[263] It is geographically the largest country in the Arabian Plate.[264]

Saudi Arabia's geography is dominated by the Arabian Desert, associated semi-desert and shrubland (see satellite image) and several mountain ranges and highlands. It is, in fact, a number of linked deserts and includes the 647,500 km2 (250,001 sq mi) Rub' al Khali ("Empty Quarter") in the southeastern part of the country, the world's largest contiguous sand desert.[113][265] There are a few lakes in the country but no permanent rivers, however wadis are very numerous. The fertile areas are to be found in the alluvial deposits in wadis, basins, and oases.[113] The main topographical feature is the central plateau which rises abruptly from the Red Sea and gradually descends into the Nejd and toward the Persian Gulf. On the Red Sea coast, there is a narrow coastal plain, known as the Tihamah parallel to which runs an imposing escarpment. The southwest province of Asir is mountainous, and contains the 3,133 m (10,279 ft) Mount Sawda, which is the highest point in the country.[113]

Except for the southwestern province of Asir, Saudi Arabia has a desert climate with very high day-time temperatures and a sharp temperature drop at night. Average summer temperatures are around 113 °F (45 °C), but can be as high as 129 °F (54 °C). In the winter the temperature rarely drops below 32 °F (0 °C). In the spring and autumn the heat is temperate, temperatures average around 84 °F (29 °C). Annual rainfall is extremely low. The Asir region differs in that it is influenced by the Indian Ocean monsoons, usually occurring between October and March. An average of 300 mm (12 in) of rainfall occurs during this period, that is about 60% of the annual precipitation.[266]

Animals

.jpg)

Animal life includes Arabian leopard, Arabian wolves, striped hyenas, mongooses, baboons, hares, sand cats, and jerboas. Animals such as gazelles, oryx, leopards and cheetahs were relatively numerous until the 19th century, when extensive hunting reduced these animals almost to extinction. Birds include falcons (which are caught and trained for hunting), eagles, hawks, vultures, sandgrouse, bulbuls etc. There are several species of snakes, many of which are venomous. Saudi Arabia is home to a rich marine life. The Red Sea in particular is a rich and diverse ecosystem. More than 1200 species of fish[267] have been recorded in the Red Sea, and around 10% of these are found nowhere else.[268] This also includes 42 species of deepwater fish.[267]

The rich diversity is in part due to the 2,000 km (1,240 mi) of coral reef extending along its coastline; these fringing reefs are 5000–7000 years old and are largely formed of stony acropora and porites corals. The reefs form platforms and sometimes lagoons along the coast and occasional other features such as cylinders (such as the Blue Hole (Red Sea) at Dahab). These coastal reefs are also visited by pelagic species of Red Sea fish, including some of the 44 species of shark. The Red Sea also contains many offshore reefs including several true atolls. Many of the unusual offshore reef formations defy classic (i.e., Darwinian) coral reef classification schemes, and are generally attributed to the high levels of tectonic activity that characterize the area. Domesticated animals include the legendary Arabian horse, Arabian camel, sheep, goats, cows, donkeys, chickens etc. Reflecting the country's dominant desert conditions, Saudi Arabia's plant life mostly consists of herbs, plants and shrubs that require little water. The date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) is widespread.[113]

Administrative divisions

Saudi Arabia is divided into 13 regions[269] (Arabic: مناطق إدارية; manatiq idāriyya, sing. منطقة إدارية; mintaqah idariyya). The regions are further divided into 118 governorates (Arabic: محافظات; muhafazat, sing. محافظة; muhafazah). This number includes the 13 regional capitals, which have a different status as municipalities (Arabic: أمانة; amanah) headed by mayors (Arabic: أمين; amin). The governorates are further sudivided into sub-governorates (Arabic: مراكز; marakiz, sing. مركز; markaz).

The 13 regions of Saudi Arabia.

Cities

| Largest cities or towns in Saudi Arabia Data.gov.sa (2013/2014/2016) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Regions | Pop. | Rank | Name | Regions | Pop. | ||

Riyadh  Jeddah |

1 | Riyadh | Riyadh | [270]6,506,700 | 11 | Qatif | Ash-Sharqiyyah | [271]559,300 |  Mecca  Medina |

| 2 | Jeddah | Makkah | [272]3,976,400 | 12 | Khamis Mushait | 'Asir | [273]549,000 | ||

| 3 | Mecca | Makkah | [272]1,919,900 | 13 | Ha'il | Ha'il | [274]441,900 | ||

| 4 | Medina | Al Madinah | [275]1,271,800 | 14 | Hafar Al-Batin | Ash-Sharqiyyah | [271]416,800 | ||

| 5 | Al-Ahsa | Ash-Sharqiyyah | [271]1,136,900 | 15 | Jubail | Ash-Sharqiyyah | [271]411,700 | ||

| 6 | Ta'if | Makkah | [272]1,109,800 | 16 | Al-Kharj | Riyadh | [276]404,100 | ||

| 7 | Dammam | Ash-Sharqiyyah | [271]975,800 | 17 | Abha | 'Asir | [273]392,500 | ||

| 8 | Buraidah | Al-Qassim | [277]658,600 | 18 | Najran | Najran | [278]352,900 | ||

| 9 | Khobar | Ash-Sharqiyyah | [271]626,200 | 19 | Yanbu | Al Madinah | [275]320,800 | ||

| 10 | Tabuk | Tabuk | [279]609,000 | 20 | Al Qunfudhah | Makkah | [272]304,400 | ||

Economy

Saudi Arabia's command economy is petroleum-based; roughly 75% of budget revenues and 90% of export earnings come from the oil industry. It is strongly dependent on foreign workers with about 80% of those employed in the private sector being non-Saudi.[280][281] Among the challenges to Saudi economy include halting or reversing the decline in per capita income, improving education to prepare youth for the workforce and providing them with employment, diversifying the economy, stimulating the private sector and housing construction, diminishing corruption and inequality.[282]

The oil industry comprises about 45% of Saudi Arabia's nominal gross domestic product, compared with 40% from the private sector (see below). Saudi Arabia officially has about 260 billion barrels (4.1×1010 m3) of oil reserves, comprising about one-fifth of the world's proven total petroleum reserves.[283]

In the 1990s, Saudi Arabia experienced a significant contraction of oil revenues combined with a high rate of population growth. Per capita income fell from a high of $11,700 at the height of the oil boom in 1981 to $6,300 in 1998.[284] Taking into account the impact of the real oil price changes on the Kingdom's real gross domestic income, the real command-basis GDP was computed to be 330.381 billion 1999 USD in 2010.[285] Increases in oil prices in the aughts helped boost per capita GDP to $17,000 in 2007 dollars (about $7,400 adjusted for inflation),[286] but have declined since oil price drop in mid-2014.[287]

OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) limits its members' oil production based on their "proven reserves." Saudi Arabia's published reserves have shown little change since 1980, with the main exception being an increase of about 100 billion barrels (1.6×1010 m3) between 1987 and 1988.[288] Matthew Simmons has suggested that Saudi Arabia is greatly exaggerating its reserves and may soon show production declines (see peak oil).[289]

From 2003–2013 "several key services" were privatized—municipal water supply, electricity, telecommunications—and parts of education and health care, traffic control and car accident reporting were also privatized. According to Arab News columnist Abdel Aziz Aluwaisheg, "in almost every one of these areas, consumers have raised serious concerns about the performance of these privatized entities."[290] The Tadawul All Share Index (TASI) of the Saudi stock exchange peaked at 16,712.64 in 2005, and closed at 8,535.60, at the end of 2013.[291] In November 2005, Saudi Arabia was approved as a member of the World Trade Organization. Negotiations to join had focused on the degree to which Saudi Arabia is willing to increase market access to foreign goods and in 2000, the government established the Saudi Arabian General Investment Authority to encourage foreign direct investment in the kingdom. Saudi Arabia maintains a list of sectors in which foreign investment is prohibited, but the government plans to open some closed sectors such as telecommunications, insurance, and power transmission/distribution over time.

The government has also made an attempt at "Saudizing" the economy, replacing foreign workers with Saudi nationals with limited success.[292]

Saudi Arabia has had five-year "Development Plans" since 1970. Among its plans were to launch "economic cities" (e.g. King Abdullah Economic City) to be completed by 2020, in an effort to diversify the economy and provide jobs. As of 2013 four cities were planned.[293] The King has announced that the per capita income is forecast to rise from $15,000 in 2006 to $33,500 in 2020.[294] The cities will be spread around Saudi Arabia to promote diversification for each region and their economy, and the cities are projected to contribute $150 billion to the GDP.

In addition to petroleum and gas, Saudi also has a small gold mining sector in the Mahd adh Dhahab region and other mineral industries, an agricultural sector (especially in the southwest) based on dates and livestock, and large number of temporary jobs created by the roughly two million annual hajj pilgrims.[282]

Statistics on poverty in the kingdom are not available through the UN resources because the Saudi government does not issue any.[295] The Saudi state discourages calling attention to or complaining about poverty. In December 2011, the Saudi interior ministry arrested three reporters and held them for almost two weeks for questioning after they uploaded a video on the topic to YouTube.[296] Authors of the video claim that 22% of Saudis may be considered poor (2009).[297] Observers researching the issue prefer to stay anonymous[298] because of the risk of being arrested.

Agriculture

Saudi Arabia encouraged desert agriculture by providing substantial subsidies as well as consuming 300 billion cubic meter of mostly non-renewable water reserves free of charge to grow alfalfa, cereals, meat and milk in the Arabian Desert.[299] Consuming non-renewable groundwater resulted in the loss of an estimated four fifths of the total groundwater reserves by 2012.[300]

Water supply and sanitation

Water supply and sanitation in Saudi Arabia is characterized by significant investments in seawater desalination, water distribution, sewerage and wastewater treatment leading to a substantial increase in access to drinking water and sanitation over the past decades. About 50% of drinking water comes from desalination, 40% from the mining of non-renewable groundwater and 10% from surface water, especially in the mountainous southwest of the country. The capital Riyadh, located in the heart of the country, is supplied with desalinated water pumped from the Persian Gulf over a distance of 467 km. Given the substantial oil wealth, water is provided almost for free. Despite improvements service quality remains poor. For example, in Riyadh water was available only once every 2.5 days in 2011, while in Jeddah it is available only every 9 days.[301] Institutional capacity and governance in the sector are weak, reflecting general characteristics of the public sector in Saudi Arabia. Since 2000, the government has increasingly relied on the private sector to operate water and sanitation infrastructure, beginning with desalination and wastewater treatment plants. Since 2008, the operation of urban water distribution systems is being gradually delegated to private companies as well.

Demographics

The population of Saudi Arabia as of July 2013 is estimated to be 26.9 million, including between 5.5 million[3] and 10 million non-nationalized immigrants,[281][302] though the Saudi population has long proved difficult to accurately estimate due to Saudi leaders' historical tendency to artificially inflate census results.[303] Saudi population has grown rapidly since 1950 when it was estimated to be 3 million,[304] and for many years had one of the highest birthrates in the world at around 3% a year.[305]

The ethnic composition of Saudi citizens is 90% Arab and 10% Afro-Asian.[306] Most Saudis live in Hejaz (35%), Najd (28%), and the Eastern Province (15%).[307] Hejaz is the most populated region in Saudi Arabia.[308]

As late as 1970, most Saudis lived a subsistence life in the rural provinces, but in the last half of the 20th century the kingdom has urbanized rapidly. As of 2012 about 80% of Saudis live in urban metropolitan areas—specifically Riyadh, Jeddah, or Dammam. [309]

Its population is also quite young with over half the population under 25 years old.[310] A large fraction are foreign nationals. (The CIA Factbook estimated that as of 2013 foreign nationals living in Saudi Arabia made up about 21% of the population.[3] Other estimates are 30%[311] or 33%[312])

As recently as the early 1960s, Saudi Arabia's slave population was estimated at 300,000.[313] Slavery was officially abolished in 1962.[314][315]

Languages

The official language of Saudi Arabia is Arabic. The three main regional variants spoken by Saudis are Hejazi Arabic (about 6 million speakers[316]), Najdi Arabic (about 8 million speakers[317]), and Gulf Arabic (about 0.2 million speakers[318]). Saudi Sign Language is the principal language of the deaf community. The large expatriate communities also speak their own languages, the most numerous of which are Tagalog (700,000), Rohingya (400,000), Urdu (380,000), and Egyptian Arabic (300,000).[319]

Religions

Virtually all Saudi citizens are Muslim[320] (officially, all are), and almost all Saudi residents are Muslim.[321][322] Estimates of the Sunni population of Saudi Arabia range between 75% and 90%, with the remaining 10–25% being Shia Muslim.[323][324][325][326][327] The official and dominant form of Sunni Islam in Saudi Arabia is commonly known as Wahhabism[328] (proponents prefer the name Salafism, considering Wahhabi derogatory[329]) and is often described as 'puritanical', 'intolerant', or 'ultra-conservative' by observers, and as "true" Islam by its adherents. It was founded in the Arabian Peninsula by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab in the eighteenth century. Other denominations, such as the minority Shia Islam, are systematically suppressed.[330]

According to estimates there are about 1,500,000 Christians in Saudi Arabia, almost all foreign workers.[331] Saudi Arabia allows Christians to enter the country as foreign workers for temporary work, but does not allow them to practice their faith openly. The percentage of Saudi Arabian citizens who are Christians is officially zero,[332] as Saudi Arabia forbids religious conversion from Islam (apostasy) and punishes it by death.[333] In spite of this, a 2015 study estimates 60,000 Muslims converted to Christianity in Saudi Arabia.[334] According to Pew Research Center there are 390,000 Hindus in Saudi Arabia, almost all foreign workers.[335]

There may be a significant fraction of atheists and agnostics in Saudi Arabia,[336][337] although they are officially called "terrorists".[338] Apostasy is punishable by death in Saudi Arabia, hence non-believers hardly ever come out.

Foreigners

Saudi Arabia's Central Department of Statistics & Information estimated the foreign population at the end of 2014 at 33% (10.1 million).[339] The CIA Factbook estimated that as of 2013 foreign nationals living in Saudi Arabia made up about 21% of the population.[3] Other sources report differing estimates.[312] Indian: 1.3 million, Pakistani: 1.5 million,[340] Egyptian: 900,000, Yemeni: 800,000, Bangladeshi: 500,000, Filipino: 500,000, Jordanian/Palestinian: 260,000, Indonesian: 250,000, Sri Lankan: 350,000, Sudanese: 250,000, Syrian: 100,000 and Turkish: 100,000.[341] There are around 100,000 Westerners in Saudi Arabia, most of whom live in compounds or gated communities.

Foreign Muslims[342] who have resided in the kingdom for ten years may apply for Saudi citizenship. (Priority is given to holders of degrees in various scientific fields,[343] and exception made for Palestinians who are excluded unless married to a Saudi national, because of Arab League instructions barring the Arab states from granting them citizenship.) Saudi Arabia is not a signatory to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention.[344]

As Saudi population grows and oil export revenues stagnate, pressure for "Saudization" (the replacement of foreign workers with Saudis) has grown, and the Saudi government hopes to decrease the number of foreign nationals in the country.[345] Saudi Arabia expelled 800,000 Yemenis in 1990 and 1991[346] and has built a Saudi–Yemen barrier against an influx of illegal immigrants and against the smuggling of drugs and weapons.[347] In November 2013, Saudi Arabia expelled thousands of illegal Ethiopian residents from the Kingdom. Various Human Rights entities have criticised Saudi Arabia's handling of the issue.[348] Over 500,000 undocumented migrant workers — mostly from Somalia, Ethiopia, and Yemen — have been detained and deported since 2013.[349]

Monarchs (1932–present)

- King Abdulaziz (1932–1953); second longest reigning Saudi monarch.

- King Saud (1953–1964); third longest reigning Saudi monarch.

- King Faisal (1964–1975); fourth longest reigning Saudi monarch.

- King Khalid (1975–1982); sixth longest reigning Saudi monarch.

- King Fahd (1982–2005); longest reigning Saudi monarch.

- King Abdullah (2005–2015); fifth longest reigning Saudi monarch.

- King Salman (2015–present); current monarch.

Crown Princes (1933–present)

.jpg)

- Crown Prince Saud bin Abdulaziz (1933–1953); became King. Crown Prince of King Abdulaziz.

- Crown Prince Faisal bin Abdulaziz (1953–1964); became King. Crown Prince of King Saud.

- Crown Prince Muhammad bin Abdulaziz (1964–1965); Resigned from post. Crown Prince of King Faisal.

- Crown Prince Khalid bin Abdulaziz (1965–1975); became King. Crown Prince of King Faisal.

- Crown Prince Fahd bin Abdulaziz (1975–1982); became King. Crown Prince of King Khalid.

- Crown Prince Abdullah bin Abdulaziz (1982–2005); became King. Crown Prince of King Fahd.

- Crown Prince Sultan bin Abdulaziz (2005–2011); died in office. Crown Prince of King Abdullah.

- Crown Prince Nayef bin Abdulaziz (2011–2012); died in office. Crown Prince of King Abdullah.

- Crown Prince Salman bin Abdulaziz (2012–2015); became King. Crown Prince of King Abdullah.

- Crown Prince Muqrin bin Abdulaziz (2015); removed from post. Crown Prince of King Salman.

- Crown Prince Mohammad bin Nayef (2015–present); incumbent. Crown Prince of King Salman.

Second Deputy Prime Minister/Second-in-line (1965–2011)

- Prince Fahd (1965–1975); became Crown Prince.

- Prince Abdullah (1975–1982); became Crown Prince.

- Prince Sultan (1982–2005); became Crown Prince.

- Prince Nayef (2009–2011); became Crown Prince.

Deputy Crown Prince/Second-in-line (2014–present)

- Prince Muqrin (2014–2015); became Crown Prince.

- Prince Mohammad (2015); became Crown Prince. Son of Prince Nayef.

- Prince Mohammad (2015–present); incumbent. Defense Minister of Saudi Arabia. Son of King Salman.

Culture

Saudi Arabia has centuries-old attitudes and traditions, often derived from Arab civilization. This culture has been heavily influenced by the austerely puritanical Wahhabi form of Islam, which arose in the eighteenth century and now predominates in the country. Wahhabi Islam has been called "the predominant feature of Saudi culture."[8]

Religion in society

Its Hejaz region and its cities Mecca and Medina are the cradle of Islam, the destination of the hajj pilgrimage, the two holiest sites of Islam.[350]

Islam is the state religion of Saudi Arabia and its law requires that all citizens be Muslims.[351] Neither Saudi citizens nor guest workers have the right of freedom of religion.[351] The official and dominant form of Islam in the kingdom – Wahhabism—arose in the central region of Najd, in the eighteenth century. Proponents call the movement "Salafism",[329] and believe that its teachings purify the practice of Islam of innovations or practices that deviate from the seventh-century teachings of Muhammad and his companions.[352] The Saudi government has often been viewed as an active oppressor of Shia Muslims because of the funding of the Wahabbi ideology which denounces the Shia faith.[353][354] Prince Bandar bin Sultan, Saudi ambassador to the United States, stated: "The time is not far off in the Middle East when it will be literally 'God help the Shia'. More than a billion Sunnis have simply had enough of them."[355]

Saudi Arabia is one of the few countries that have "religious police" (known as Haia or Mutaween), who patrol the streets "enjoining good and forbidding wrong" by enforcing dress codes, strict separation of men and women, attendance at prayer (salat) five times each day, the ban on alcohol, and other aspects of Sharia (Islamic law). (In the privacy of the home behavior can be far looser, and reports from the Daily Mail and WikiLeaks indicate that the ruling Saudi Royal family applies a different moral code to itself, indulging in parties, drugs and sex.[356])

Until 2016, the kingdom used the lunar Islamic calendar, not the international Gregorian calendar,[357] but in 2016 the kingdom announced its switch to the Gregorian calendar for civil purposes.[358]

Daily life is dominated by Islamic observance. Businesses are closed three or four times a day[359] for 30 to 45 minutes during business hours while employees and customers are sent off to pray.[360] The weekend is Friday-Saturday, not Saturday-Sunday, because Friday is the holiest day for Muslims.[113][361] For many years only two religious holidays were publicly recognized – ʿĪd al-Fiṭr and ʿĪd al-Aḍḥā. (ʿĪd al-Fiṭr is "the biggest" holiday, a three-day period of "feasting, gift-giving and general letting go".[362])

As of 2004 approximately half of the broadcast airtime of Saudi state television was devoted to religious issues.[363] 90% of books published in the kingdom were on religious subjects, and most of the doctorates awarded by its universities were in Islamic studies.[364] In the state school system, about half of the material taught is religious. In contrast, assigned readings over twelve years of primary and secondary schooling devoted to covering the history, literature, and cultures of the non-Muslim world comes to a total of about 40 pages.[363]

.jpg)

"Fierce religious resistance" had to be overcome to permit such innovations as paper money (in 1951), female education (1964), and television (1965) and the abolition of slavery (1962).[365] Public support for the traditional political/religious structure of the kingdom is so strong that one researcher interviewing Saudis found virtually no support for reforms to secularize the state.[366]

Because of religious restrictions, Saudi culture lacks any diversity of religious expression, buildings, annual festivals and public events.[367][368] Celebration of other (non-Wahhabi) Islamic holidays, such as the Muhammad's birthday and the Day of Ashura, (an important holiday for the 10–25% of the population[324][325][326] that is Shīʿa Muslim), are tolerated only when celebrated locally and on a small scale.[369] Shia also face systematic discrimination in employment, education, the justice system according to Human Rights Watch.[370] Non-Muslim festivals like Christmas and Easter are not tolerated at all,[371] although there are nearly a million Christians as well as Hindus and Buddhists among the foreign workers.[372][371] No churches, temples or other non-Muslim houses of worship are permitted in the country. Proselytizing by non-Muslims and conversion by Muslims to another religion is illegal,[372] and as of 2014 the distribution of "publications that have prejudice to any other religious belief other than Islam" (such as Bibles), was reportedly punishable by death.[373] In legal compensation court cases (Diyya) non-Muslim are awarded less than Muslims.[371] Atheists are legally designated as terrorists.[374] And at least one religious minority, the Ahmadiyya Muslims, had its adherents deported,[375] as they are legally banned from entering the country.[376]

Islamic heritage sites