Kingdom of Libya

| Kingdom of Libya | ||||||||||||||

| المملكة الليبية Al-Mamlakah Al-Lībiyya Regno di Libia | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Anthem Libya, Libya, Libya | ||||||||||||||

.svg.png) | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Tripoli / Benghazi / Baydaa | |||||||||||||

| Languages | Arabic Berber Italian | |||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | |||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | |||||||||||||

| King | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1951–1969 | Idris I | ||||||||||||

| Crown Prince Regent | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1962 | Hasan | ||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1951–1954 | Mahmud al-Muntasir | ||||||||||||

| • | 1968–1969 | Wanis al-Qaddafi | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | |||||||||||||

| • | Upper house | Senate | ||||||||||||

| • | Lower house | House of Representatives | ||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||

| • | Independence | 24 December 1951 | ||||||||||||

| • | Coup d'état | 1 September 1969 | ||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1954 | 1,759,530 km2 (679,360 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1954 est. | 1,091,830 | ||||||||||||

| Density | 1/km2 (2/sq mi) | |||||||||||||

| Currency | Libyan pound | |||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| a. | The Kingdom had two capitals. | |||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Libya | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Libya (Arabic: المملكة الليبية; Libyan Kingdom; Italian: Regno di Libia), originally called the United Kingdom of Libya, came into existence upon independence on 24 December 1951 and lasted until a coup d'état led by Muammar Gaddafi on 1 September 1969 overthrew King Idris of Libya and established the Libyan Arab Republic.

History

Constitution

Under the constitution of October 1951, the federal monarchy of Libya was headed by King Idris as chief of state, with succession to his designated heirs. Substantial political power resided with the king. The executive arm of the government consisted of a prime minister and Council of Ministers designated by the king but also responsible to the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of a bicameral legislature. The Senate, or upper house, consisted of eight representatives from each of the three provinces. Half of the senators were nominated by the king, who also had the right to veto legislation and to dissolve the lower house. Local autonomy in the provinces was exercised through provincial governments and legislatures. Tripoli and Benghazi served alternately as the national capital.

Political development

Several factors, rooted in Libya's history, affected the political development of the newly independent country. They reflected the differing political orientations of the provinces and the ambiguities inherent in Libya's monarchy. First, after the first Libyan general election, 1952, which were held on 19 February, political parties were abolished. The National Congress Party, which had campaigned against a federal form of government, was defeated throughout the country. The party was outlawed, and Bashir es Sadawi was deported. Second, provincial ties continued to be more important than national ones, and the federal and provincial governments were constantly in dispute over their respective spheres of authority. A third problem derived from the lack of a direct heir to the throne. To remedy this situation, Idris in 1953 designated his sixty-year-old brother to succeed him. When the original heir apparent died, the king appointed his nephew, Prince Hasan ar Rida, his successor.

Foreign policy

In its foreign policy, the Kingdom of Libya was recognized as belonging to the conservative traditionalist bloc in the League of Arab States, of which it became a member in 1953.[1]

The government was in close alliance with the United States and United Kingdom; both countries maintained military base rights in Libya. The U.S. supported the United Nations resolution providing for Libyan independence in 1951 and raised the status of its office at Tripoli from a consulate general to a legation. Libya opened a legation at Washington, D.C. in 1954. Both countries subsequently raised their missions to the embassy level and exchanged ambassadors.

In 1953, Libya concluded a twenty-year treaty of friendship and alliance with the United Kingdom under which the latter received military bases in exchange for financial and military assistance. The next year, Libya and the United States signed an agreement under which the United States also obtained military base rights, subject to renewal in 1970, in return for economic aid to Libya. The most important of the United States installations in Libya was Wheelus Air Base, near Tripoli, considered a strategically valuable installation in the 1950s and early 1960s. Reservations set aside in the desert were used by British and American military aircraft based in Europe as practice firing ranges. Libya forged close ties with France, Italy, Greece, Turkey, and established full diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in 1955, but declined a Soviet offer of economic aid.

As part of a broad assistance package, the UN Technical Assistance Board agreed to sponsor a technical aid program that emphasized the development of agriculture and education. The University of Libya was founded in 1955 by royal decree in Benghazi. Foreign powers, notably Britain and the United States, provided development aid. Steady economic improvement occurred, but the pace was slow, and Libya remained a poor and underdeveloped country heavily dependent on foreign aid.

Development of the nation

This situation changed suddenly and dramatically in June 1959 when research prospectors from Esso (later renamed Exxon) confirmed the location of major petroleum deposits at Zaltan in Cyrenaica. Further discoveries followed, and commercial development was quickly initiated by concession holders who returned 50 percent of their profits to the Libyan government in taxes. In the petroleum market, Libya's advantages lay not only in the quantity but also in the high quality of its crude product. Libya's proximity and direct linkage to Europe by sea were further marketing advantages. The discovery and exploitation of petroleum turned the vast, sparsely populated, impoverished country into an independently wealthy nation with potential for extensive development and thus constituted a major turning point in Libyan history. Libya's petroleum law, initially passed in 1955, was amended in 1961 and again in 1965 to increase the Libyan government's share of the revenues from oil.[2]

As development of petroleum resources progressed in the early 1960s, Libya launched its first Five-Year Plan, 1963-68. One negative result of the new wealth from petroleum, however, was a decline in agricultural production, largely through neglect. Internal Libyan politics continued to be stable, but the federal form of government had proven inefficient and cumbersome. In April 1963, Prime Minister Mohieddin Fikini secured adoption by parliament of a bill, endorsed by the king, that abolished the federal form of government, establishing in its place a unitary, monarchical state with a dominant central government. By legislation, the historical divisions of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania, and Fezzan were to be eliminated and the country divided into ten new provinces, each headed by an appointed governor. The legislature revised the constitution in 1963 to reflect the change from a federal to a unitary state.

International relations

In regional affairs, Libya enjoyed the advantage of not having aggravated boundary disputes with its neighbors. Libya was one of the thirty founding members of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), established in 1963, and in November 1964 participated with Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia in forming a joint consultative committee aimed at economic cooperation among North African states. Although it supported Arab causes, including the Moroccan and Algerian independence movements, Libya took little active part in the Arab-Israeli dispute or the tumultuous inter-Arab politics of the 1950s and the early 1960s.[3]

Nevertheless, the brand of Arab nationalism advanced by Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser exercised an increasing influence, particularly among the younger Libyan generation that were influenced by the influx of Egyptian teachers into Libya. As one report suggests:

The presence of Egyptian teachers explains why so many classrooms show the influence of Egyptian propaganda. Pupils do crayon drawings of Egyptian troops winning victories over Israel or Britain. In Benghazi, Libya, a complete course in Egyptian history is given to secondary school students. A display in a high school art exhibit showed pictures of the leading rules of Egypt; on one side were the “bad” rulers, on the other the “good” rulers. The bad rulers began with the Pharaoh Cheops, who enslaved his people to build the pyramids, and ended with Farouk. The good rulers began with the idealistic Pharaoh Ikhnaton and ended with, of course, Gamal Abdel Nasser.[4]

In response to anti-Western agitation in 1964, Libya's essentially pro-Western government requested the evacuation of British and American bases before the dates specified in the treaties. Most British forces were in fact withdrawn in 1966, although the evacuation of foreign military installations, including Wheelus Air Base, was not completed until March 1970.

The June 1967 War between Israel and its Arab neighbors aroused a strong reaction in Libya, particularly in Tripoli and Benghazi, where dock and oil workers as well as students were involved in violent demonstrations. The United States and British embassies and oil company offices were damaged in rioting. Members of the small Jewish community were also attacked, prompting the emigration of almost all remaining Libyan Jews. The government restored order, but thereafter attempts to modernize the small and ineffective Libyan armed forces and to reform the grossly inefficient Libyan bureaucracy foundered upon conservative opposition to the nature and pace of the proposed reforms.

Although Libya was clearly on record as supporting Arab causes in general, the country did not play an important role in Arab politics. At the Arab summit conference held at Khartoum in September 1967, however, Libya, along with Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, agreed to provide generous subsidies from oil revenues to aid Egypt, Syria, and Jordan, defeated in June by Israel. Also, Idris first broached the idea of taking collective action to increase the price of oil on the world market. Libya, nonetheless, continued its close association with the West, while Idris' government steered an essentially conservative course at home.

Attempts at reform

After the forming of the Libyan state in 1951, Idris' government had tried—not very successfully—to promote a sense of Libyan nationalism built around the institution of the monarchy. But Idris himself was first and foremost a Cyrenaican, never at ease in Tripolitania. His political interests were essentially Cyrenaican, and he understood that whatever real power he had—and it was more considerable than what he derived from the constitution—lay in the loyalty he commanded as emir of Cyrenaica and head of the Sanussi order. Idris' pro-Western sympathies and identification with the conservative Arab bloc were especially resented by an increasingly politicized urban elite that favored nonalignment. Aware of the potential of their country's natural wealth, many Libyans had also become conscious that its benefits reached very few of the population. An ominous undercurrent of dissatisfaction with corruption and malfeasance in the bureaucracy began to appear as well, particularly among young officers of the armed forces who were influenced by Nasser's Arab nationalist ideology.

Alienated from the most populous part of the country, from the cities, and from a younger generation of Libyans, Idris spent more and more time at his palace in Tobruk, near the British military base. In June 1969, the king left the country for rest and medical treatment in Greece and Turkey, leaving Crown Prince Hasan as-Senussi as regent.

1969 coup and end of the monarchy

The monarchy came to an end on 1 September 1969 when a group of military officers led by Muammar Gaddafi staged a coup d’état against King Idris while he was in Turkey for medical treatment. The revolutionaries arrested the army chief of staff and the head of security in the kingdom. After hearing about the coup, King Idris dismissed it as "unimportant".[5]

The coup pre-empted King Idris' instrument of abdication dated 4 August 1969 to take effect 2 September 1969 in favour of the Crown Prince, who had been appointed regent following the king's departure for Turkey. Following the overthrow of the monarchy the country was renamed the Libyan Arab Republic.

Aftermath

2011 Libyan revolution

Although the king and the crown prince died in exile and most of the younger generation of Libyans were born after the monarchy, the Senussi dynasty has enjoyed somewhat of a comeback during the 2011 Libyan civil war, especially in the dynasty's traditional stronghold of Cyrenaica. Opposition demonstrators to Colonel Gaddafi used the old tricolour flag of the monarchy, some carried portraits of the king,[6] and played the old national anthem Libya, Libya, Libya. Two of the surviving Senussi exiles were planning to return to Libya to support the protestors.

Government

The United Kingdom of Libya was a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with legislative power being exercised by the monarch in conjunction with parliament.

King

| King of Libya | |

|---|---|

|

| |

|

Idris I | |

| Details | |

| First monarch | Idris I |

| Last monarch | Idris I |

| Formation | 24 December 1951 |

| Abolition | 1 September 1969 |

| Residence | Royal Palace |

| Appointer | Hereditary |

| Pretender(s) | Mohammed El Senussi |

The King was defined by the constitution as the supreme head of state. Before he is able to assume constitutional powers the King would need to take an oath before a joint session of the Senate and the House of Representatives. All laws passed by parliament needed to be sanctioned and promulgated by the king. It was also the king's responsibility to open and close the sessions of Parliament, it is also his responsibility to dissolve the House of Representatives in line with the constitution. The king was head of the kingdom's armed forces.

Council of ministers

.jpg)

The King was responsible for appointing and removing Prime Ministers. The king also appointed and dismissed ministers based on the advice of the Prime Minister. The Council of Ministers were responsible for the direction of the internal and external affairs of the country and the council were accountable to the House of Representatives. Once a prime minister was removed from office this automatically resulted in dismissal of all the other ministers.

Parliament

The Kingdom's parliament consisted of two chambers, the Senate and the House of Representatives. Both chambers met and closed at the same time.

The Senate was made up of twenty-four members appointed by the King. A seat in the Senate was restricted to Libyan nationals of at least forty years. The King appointed the President of the Senate, with the Senate itself electing two vice presidents which the King would then need to approve. The president and vice president served for a fixed two-year term. At the end of this term, the King was free to reappoint the president or replace them with someone else while the vice presidents faced re-election. The term of office for a senator was eight years. A senator could not serve for consecutive terms but could be reappointed in the future. Half of all the senators were to be replaced every four years.

Members of the House of Representatives were elected through universal suffrage following the constitutional change on 25 April 1963. Women had previously not been able to vote. The number of deputies in the house was determined on the basis of one deputy for twenty thousand people. Elections were held every four years unless parliament was dissolved earlier. The deputies were responsible for electing a speaker and two vice-speakers for the house.

Subdivisions

Provinces

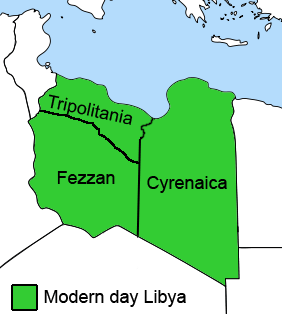

Following independence until 1963, the Kingdom was organised into three provinces: Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan, which are the three historic regions of Libya. Autonomy in the provinces was exercised through provincial governments and legislatures.

| Province | Capital | Area[7] |

|---|---|---|

| Tripolitania | Tripoli | 106,500 sq mi (276,000 km2) |

| Cyrenaica | Benghazi | 330,000 sq mi (850,000 km2) |

| Fezzan | Sabha | 243,500 sq mi (631,000 km2) |

1963 reorganisation

Following a change in the constitution abolishing the federal makeup of the country in 1963 the three provinces were reorganised into ten governorates (muhafazah in Arabic) which were ruled by an appointed governor.[8][9]

- Bayda, formerly part of Cyrenaica

- Al Khums, formerly part of Tripolitania

- Awbari, formerly part of Fezzan

- Az Zawiyah, formerly part of Tripolitania

- Benghazi, formerly part of Cyrenaica

- Darnah, formerly part of Cyrenaica

- Gharian, formerly part of Fezzan and Tripolitania

- Misrata, formerly part of Tripolitania

- Sabha, formerly part of Fezzan

- Tarabulus, formerly part of Tripolitania

See also

References

- ↑ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress (1987), "Independent Libya", U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved July 14, 2006.

- ↑ Vandewalle, Dirk J. (2006), A history of modern Libya, Cambridge University Press, p. 59, ISBN 978-0-521-85048-3

- ↑ Abadi, Jacob (2000), "Pragmatism and Rhetoric in Libya's Policy Toward Israel", The Journal of Conflict Studies: Volume XX Number 1 Fall 2000, University of New Brunswick. Retrieved July 19, 2006.

- ↑ Wynn, Wilton (1959). Nasser Of Egypt: The Search For Dignity. Clinton, MA: Colonial Press. p. 137.

- ↑ 1969: Bloodless coup in Libya, BBC

- ↑ "The liberated east: Building a new Libya". The Economist. 24 February 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ↑ Villard, Henry Serrano (1956), Libya: the new Arab kingdom of North Africa, Cornell University Press, p. 26

- ↑ Modern history in politics (in Arabic). Libya's future. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ↑ "Municipalities of Libya"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kingdom of Libya. |

- Kingdom of Libya's constitution

- Libya at worldstatesmen.org.

- Birth of a nation

- Independent Libya

.gif)