Telephus

- This article is about Telephus the son of Heracles. The name also refers to the father of Cyparissus.

In Greek mythology, Telephus (/ˈtɛlɪfəs/; Greek: Τήλεφος, Tēlephos, "far-shining")[1] was the son of Heracles and Auge, daughter of king Aleus of Tegea; and the father of Eurypylus. He was intended to be king of Tegea, but instead became the king of Mysia in Asia Minor. He was wounded by the Achaeans when they were coming to sack Troy and bring back Helen to Sparta.

Birth

Aleus, king in Tegea and father of Auge, had been told by an oracle that he would be overthrown by his grandson.[2] So, according to varying myths, he forced Auge to become a virginal priestess of Athena Alea, in which condition she was violated by Heracles. Although the infant Telephus was hidden in the temple, his cries revealed his presence and Aleus ordered the child exposed on Mt. Parthenion, the "mountain of the Virgin". The child was suckled by a deer through the agency of Heracles, although the Pergamon Altar depicts Telephus being suckled by a lion. Alternatively, Aleus put Auge and the baby in a crate that was set adrift on the sea[3] and washed up on the coast of Mysia in Asia Minor. Alternatively, Aleus exposed Telephus and sold Auge into slavery; she was thereby given as a gift to King Teuthras.

In either case, Telephus was adopted, either by King Corycus or by King Creon.

Telephus and Auge

Telephus' companion Parthenopaeus was destined to die at the gates of Thebes, but Telephus was destined to rule foreign lands and fight his fellow Greeks before they reached Troy. The two companions went off to Asia Minor to look for land to make their kingdom. They eventually came to Mysia, where they aided King Teuthras in a war and defeated the enemy. For this the King gave Telephus the hand of his beautiful adopted daughter Auge.

Auge, who was still consecrated to the memory of Heracles, privately refused her father's decision and planned Telephus' death. She secreted a knife in the marriage bed and on the wedding night tried to kill Telephus, but Heracles separated the two with a flash of lightning and they both recognized each other as mother and son.

Telephus as king of Mysia versus the Achaeans

Telephus succeeded Teuthras as king of the Mysians. When the Greeks first assembled at Aulis and left for the Trojan War, they accidentally found themselves in Mysia, where they were opposed by some fellow Achaeans. Paris and Helen had stopped in Mysia on their way to Troy, and had asked Telephus to fight off the Achaeans should they come. In another version of the myth, as depicted on the interior frieze of the Pergamon Altar, Telephus was married to the Amazon Hiera. She brought a force of Amazons to aid in the fighting, but was herself killed in the battle. In the battle Achilles wounded Telephus, who killed Thersander the King of Thebes. This explains why in the Iliad there is no Theban King.

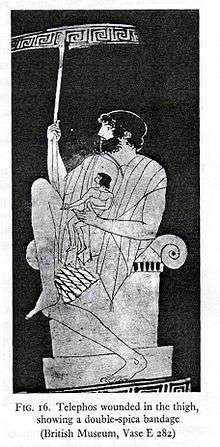

Telephus' wound

The wound would not heal and Telephus consulted the oracle of Delphi about it. The oracle responded in a mysterious way that "he that wounded shall heal". Telephus convinced Achilles to heal his wound in return for showing the Achaeans the way to Troy, thus resolving the conflict.

According to reports about Euripides' lost play Telephus, he went to Aulis pretending to be a beggar; there he asked Clytemnaestra, the wife of Agamemnon, what he should do to be healed. She had three reasons to help him: she was related to Heracles; Heracles fought a war that made her father King of Sparta; and she was angry at her husband. Some versions say that Telephus promised to marry Clytemnaestra in return for her aid. Although he did not marry Clytemnaestra, she helped him by telling him to kidnap her only son Orestes, and to threaten to kill Orestes if Achilles would not heal Telephus' wound.

When Telephus threatened the young child, Achilles refused, claiming to have no cathartic knowledge. Odysseus, however, reasoned that the spear that had inflicted the wound must be able to heal it. Pieces of the spear were scraped off onto the wound, and Telephus healed. This is an example of sympathetic magic. Afterwards Telephus guided the Achaeans to Troy.[4]

The Achaeans asked Telephus to join them. However he declined their offer, saying that he was the son-in-law of King Priam through his wife.[5]

Telephus' wives

Different traditions ascribe different wives to Telephus, usually either a daughter of Priam or a daughter of Teuthras. Marriage to a daughter of Priam, either Laodice[6] or Astyoche,[7] generally accounts for Telephus' refusal to attack Troy along with the Greek armies. (Servius makes Astyoche the sister of Priam and daughter of Laomedon, and calls her the mother of Telephus' son Eurypylus.)[8] According to Diodorus Siculus, Telephus was married to Argiope, the daughter of Teuthras, after it was discovered that Auge was his mother.[9] Philostratus, however, in his Heroicus, makes Hiera the wife of Telephus (she is erroneously called an Amazon by some; Philostratus only says that the Mysian women fight ὥσπερ Ἀμαζόνες, "like Amazons"). Hiera is killed in battle by Nireus.[10] This version is also depicted on the Pergamon Altar.

Eurypylus

Telephus led his Mysian forces towards Troy in order to help his father-in-law King Priam.[11] Telephus' son Eurypylus was supposed to succeed to the Mysian throne, but Achilles' son Neoptolemus killed Eurypylus at Troy.[12]

Telephus in the arts

Telephus features in Sophocles' The Assembly of the Achaeans and Euripides' Telephus.

The character Dicaeopolis in Aristophanes' play The Acharnians takes on the role of Telephus for comic and metatheatrical effect.

The story of Telephus turning back the Greeks at Mysia is told in the poem of Archilochus found in modern times in the Oxyrhynchus Papyri (P.Oxy 4708).

Telephus' story is the subject of the Telephus Frieze that forms a part of the famous Pergamon Altar.

Notes

- ↑ See for example, Knight, p. 433. According to the mythographic tradition, Telephus' name derived from his being suckled by a doe, e.g. Apollodorus, Library 2.7.4 (Frazer note 2 to AP 2.7.4: 'Apollodorus seems to derive the name Telephus from θηλή, “a dug,” and ἔλαφος, “a doe."'). See also Huys p.295 ff.; Webster pp 238–239; Hyginus, Fabulae 99; Diodorus Siculus, 4.33.11; Moses of Chorene, Progymnasm 3.3: "He got his name from circumstances". According to Kerenyi his name was "more accurately ... Telephanes, 'he who shines afar'" (Kerenyi, p. 337). The feminine form is Telephassa, of whom Karl Kerenyi writes, "She bore the lunar name Telephassa or Telephae, 'she who illuminates afar', or Argiope 'she of the white face'". (Kerenyi, p. 27).

- ↑ This Succession Myth, a fate parallel to the succession of the gods Cronus and Zeus, is also told of sons of Metis and Thetis.

- ↑ Compare Danaë and the infant Perseus.

- ↑ Telephus' role in the expedition has thus been seen as an instance of a common story-pattern in which a character provides a hero with information necessary for his primary quest, only after he is won over in a "preliminary adventure" (Davies 2000:9-10).

- ↑ Hyginus fab. 101, Dictys Cretensis 2.5

- ↑ Hyginus fab. 101

- ↑ Dictys Cretensis 2.5

- ↑ Servius, on Ecl. 6.72

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus 4.33

- ↑ Philostratus, Heroicus 23.26–29.

- ↑ "Telephus". Greek Mythology Link. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Dictys of Crete, 4.14–18

References

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921.

- Davies, Malcolm (2000). "Euripides Telephus Fr. 149 (Austin) and the Folk-Tale Origins of the Teuthranian Expedition" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 133: 7–10.

- Diodorus Siculus, Diodorus Siculus: The Library of History. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. Twelve volumes. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1989. Vol. 2. Books 2.35–4.58. ISBN 0-674-99334-9

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, The Myths of Hyginus. Edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960.

- Kerenyi, Karl (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks. Thames and Hudson. pp. 337–341.

- Huys, Marc, The Tale of the Hero Who Was Exposed at Birth in Euripidean Tragedy: A Study of Motifs, Cornell University Press (December 1995). ISBN 978-90-6186-713-5.

- Knight, Richard Payne, The symbolical language of ancient art and mythology, Kessinger Publishing, 1892

- Webster, Thomas Bertram Lonsdale, The Tragedies of Euripides, Methuen & Co, 1967 ISBN 978-0-416-44310-3

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Te'lephus"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Telephus. |