London King's Cross railway station

| King's Cross | |

|---|---|

| London King's Cross | |

|

King's Cross station frontage following restoration, in 2014 | |

King's Cross Location of King's Cross in Central London | |

| Location | Kings Cross |

| Local authority | London Borough of Camden |

| Managed by | Network Rail |

| Owner | Network Rail |

| Station code | KGX |

| DfT category | A |

| Number of platforms | 12 (numbered 0–11) |

| Accessible | Yes |

| Fare zone | 1 |

| OSI |

King's Cross St. Pancras London St. Pancras Int'l London Euston |

| Cycle parking | Yes – platforms 0 & 1, 8, 9 and car park racks |

| Toilet facilities | Yes |

| National Rail annual entry and exit | |

| 2011–12 |

|

| – interchange |

|

| 2012–13 |

|

| – interchange |

|

| 2013–14 |

|

| – interchange |

|

| 2014–15 |

|

| – interchange |

|

| 2015–16 |

|

| – interchange |

|

| Railway companies | |

| Original company | Great Northern Railway |

| Pre-grouping | Great Northern Railway |

| Post-grouping | London and North Eastern Railway |

| Key dates | |

| 1852 | Opened |

| Other information | |

| Lists of stations | |

| External links | |

| WGS84 | 51°31′51″N 0°07′24″W / 51.5309°N 0.1233°WCoordinates: 51°31′51″N 0°07′24″W / 51.5309°N 0.1233°W |

|

| |

King's Cross railway station, also known as London King's Cross, is a Central London railway terminus on the northern edge of the city. It is one of the busiest railway stations in the United Kingdom, being the southern terminus of the East Coast Main Line to North East England and Scotland.

The station was opened in 1852 by the Great Northern Railway in the Kings Cross area to accommodate the East Coast Main Line. It quickly grew to cater for suburban lines and was expanded several times in the 19th century. It came under ownership of the London and North Eastern Railway as part of the Big Four grouping in 1923, who introduced famous services such as the Flying Scotsman and locomotives such as Mallard. The station complex was redeveloped in the 1970s, simplifying the layout and providing electric suburban services, and it became a major terminus for the high-speed InterCity 125. As of 2017, long-distance trains from King's Cross are run by Virgin Trains East Coast to Edinburgh Waverley and Glasgow Central via York and Newcastle; other long-distance operators include Hull Trains and Grand Central. In addition, Great Northern runs suburban commuter trains in and around north London.

In the late 20th century, the area around the station became known for its seedy and downmarket character, and was used as a backdrop for several films as a result. There was major redevelopment in the 21st century, including restoration of the original roof, and the station became well known for its association with the Harry Potter books and films, particularly the fictional Platform 9¾.

Adjacent to King's Cross station is St. Pancras International, the London terminus for Eurostar services to continental Europe. Beneath both main line stations is King's Cross St. Pancras tube station on the London Underground, and combined they form one of the country's largest transport hubs.

Location and name

The station is located on the London Inner Ring Road at the eastern end of Euston Road, next to the junction with Pentonville Road, Gray's Inn Road and York Way. To the west, at the other side of Pancras Road, is St. Pancras railway station.[3] Several London bus routes, including 10, 30, 59, 73, 91, 205, 390, 476 pass in front of or to the side of the station.[4]

King's Cross is spelled both with and without an apostrophe. King's Cross is used in signage at the Network Rail and London Underground stations, on the Tube map and on the official Network Rail webpage.[5] It rarely featured on early Underground maps, but has been consistently used on them since 1951.[6] Kings X, Kings + and London KX are abbreviations used in space-limited contexts. The National Rail station code is KGX.[7]

History

Early history

The area of King's Cross was previously a village known as Battle Bridge which was an ancient crossing of the River Fleet, originally known as Broad Ford, later Bradford Bridge. The river flowed along what is now the west side of Pancras Road until it was rerouted underground in 1825.[8] The name "Battle Bridge" is linked to tradition that this was the site of a major battle between the Romans and the Celtic British Iceni tribe led by Boudica. According to folklore, King's Cross is the site of Boudica's final battle and some sources say she is buried under one of the platforms.[9] Platforms 9 and 10 have been suggested as possible sites.[9][10] Boudica's ghost is also reported to haunt passages under the station, around platforms 8–10.[11]

Great Northern Railway (1850–1923)

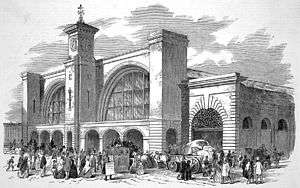

King's Cross station was built in 1851–1852 as the London terminus of the Great Northern Railway (GNR), and was the fifth London terminal to be constructed.[12] It replaced a temporary station next to Maiden Lane (now York Way) that had been quickly constructed with the line's arrival in London in 1850.[13]

The station took its name from the King's Cross building, a monument to King George IV that stood in the area and was demolished in 1845.[14] Construction was on the site of a smallpox hospital and it replaced a temporary terminus at Maiden Lane that had opened on 7 August 1850.[15]

Plans for the station were made in December 1848 under the direction of George Turnbull, resident engineer for constructing the first 20 miles (32 km) of the Great Northern Railway out of London.[16][17] The station's detailed design was by Lewis Cubitt, the brother of Thomas Cubitt (the architect of Bloomsbury, Belgravia and Osborne House), and Sir William Cubitt (who was chief engineer of The Crystal Palace built in 1851, and consulting engineer to the Great Northern and South Eastern Railways). The design comprised two great arched train sheds, with a brick structure at the south end designed to reflect the arches behind.[18] Its main feature was a 112-foot (34 m) high clock tower that held treble, tenor and bass bells, the latter weighing 1 ton 9 cwt (1.47 tonnes).[19] In size, it was inspired by the 200 yards (180 m) long Moscow Riding Academy of 1825,[20] leading to its built length of 268 yards (245 m).[12][lower-alpha 1]

_p138_-_King's_Cross_Station_(plan).jpg)

The station, the biggest in England, opened on 14 October 1852.[12] Originally it had one arrival and one departure platform (today's platforms 1 and 8), and the space between used for carriage sidings.[13] The platforms have been reconfigured several times. They have been numbered 1 to 8 since 1972.[21] Suburban traffic quickly grew with the opening of stations at Hornsey in 1850, Holloway Road in 1856, Wood Green in 1859 and Seven Sisters Road (now Finsbury Park) in 1861. Midland Railway services to Leicester via Hitchin and Bedford began running from King's Cross on 1 February 1858.[22] More platforms were added in 1862; No. 2 was full-length but No. 3 was stepped into the northern end of the station.[23] In 1866, a connection was made via the Metropolitan Railway to the London, Chatham and Dover Railway at Farringdon, with goods and passenger services to South London via Herne Hill.[24] A separate suburban station to the west of the main building, housing platforms 9–11 As of 1972 and known initially as "Kings Cross Main Line (Local) Station", opened in August 1875. It was followed by a connection to the Metropolitan line on 1 February 1878.[25] Two platforms (now 5 and 6) were opened on 18 December 1893 to cater for increased traffic demands. An iron footbridge was built halfway down the train shed to connect all the platforms.[26] By 1880, half the traffic at King's Cross was suburban.[27]

A significant bottleneck in the early years of operations was at Gas Works tunnel underneath the Regent's Canal immediately to the north of the station, which was built with a single up and down track. Commercial traffic was further impeded by having to cross over on-level running lines to reach the goods yard.[24] Grade separation of goods traffic was achieved by constructing the skew bridge that opened in August 1877 and the second and third Gas Works tunnels opened in 1878 and 1892 respectively.[28]

On 15 September 1881, a light engine and a coal train collided near the mouth of Copenhagen Tunnel north of the station because of a signalman's error. One person was killed and another was severely injured.[29] Bad weather contributed to flooding in the tunnels. One such incident in July 1901 suspended all traffic from the station for more than four hours, which happened at no other London terminus.[30]

King's Cross sustained no damage during World War I even though large amounts of high explosives were carried to the station in passenger trains during this time. Where possible, trains were parked in tunnels in the event of enemy aircraft overhead.[31]

London and North Eastern Railway (1923–1948)

.jpg)

Kings Cross came into the ownership of the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) following the Railways Act 1921. The LNER made improvements to various amenities, including toilets and dressing rooms underneath what is now platform 8.[32] The lines through the Gas Works tunnels were remodelled between 1922 and 1924 and improved signalling made it easier to manage the increasing number of local trains.[33]

A number of famous trains have been associated with King's Cross, such as the Flying Scotsman service to Edinburgh.[34] The Gresley A3 and later streamlined A4 Pacific steam locomotives handled express services from the 1930s until 1966.[35] The most famous of these was Mallard, which holds the world speed record for steam locomotives at 126 miles per hour (203 km/h), set in 1938.[36]

King's Cross handled large numbers of troops alongside civilian traffic during World War II. Engine shortages meant that up to 2,000 people had to be accommodated on each train. In the early hours of Sunday 11 May 1941, two 1,000 pounds (450 kg) bombs fell on the west side of the station, destroying the general offices, booking hall and a bar, and blowing out a large section of roof. Twelve people were killed; the death total would have been higher if the blast had occurred during a busy period.[37]

On 4 February 1945, a passenger train to Leeds and Bradford stalled in Gasworks Tunnel, ran back and was derailed in the station. Two people were killed and 25 were injured. Services were not fully restored until 23 February.[38][39]

British Rail (1948–1996)

Diesel services were introduced during the 1950s when steam was being phased out. All main line services were converted to diesel by June 1963.[37] Platform numbers were reorganised in 1972, to run consecutively from 1 (east) to 14 (west). The track layout was simplified in the 1970s by reusing an old flyover for freight near the Copenhagen Tunnels at Holloway, and reducing the number of running lanes through the Gas Works tunnels from six to four. At the same time, electrification started with the installation of a 25kV overhead line to cater for suburban services. The works were completed on 3 April 1977.[40] Electric services began running from King's Cross to Hertford, Welwyn Garden City and Royston; one of the few service improvements made in the area under the late 1970s Labour government.[41]

The construction of the Victoria line and its interchange at King's Cross was seen by British Rail as an opportunity to modernise the station.[42] In 1972, an in-house designed single-storey extension containing the main passenger concourse and ticket office was built at the front of the station. Although intended to be temporary, it was still standing 40 years later obscuring the Grade I-listed façade of the original station.[43] Before the extension was built, the façade was hidden behind a small terrace of shops. The extension was demolished in late 2012,[44] revealing the Lewis Cubitt architecture. In its place, the 75,000 square feet (7,000 m2) King's Cross Square was created, which was opened to the public on 26 September 2013.[45]

On 10 September 1973, a Provisional IRA bomb exploded in the booking hall at 12.24 p.m., causing extensive damage and injuring six people, some seriously. The 3 lb (1.4 kg) device was thrown without warning by a youth who escaped into the crowd and was not caught.[46]

King's Cross was a London terminus for InterCity 125 high speed services, along with Paddington. By 1982, almost all long-distances trains leaving King's Cross were 125s. The service proved to be popular, and the station saw regular queues across the concourse to board departing trains.[47]

The King's Cross fire in 1987 started in the machine room for a wooden escalator between the main line station and the London Underground station's Piccadilly line platforms. The escalator burnt up and much of the tube station caught fire with smoke spreading to the main line station, killing 31 people.[48]

In 1987, British Rail proposed building a new station with four platforms for international trains through the Channel Tunnel, and four for Thameslink trains under King's Cross. After six years of design work, the plans were abandoned, and the international terminal was constructed at St. Pancras.[27]

Privatisation (1996 – present)

Before privatisation, the King's Cross area had a reputation for run-down buildings and prostitution services in front of the main entrance. A major clean-up took place during the 1990s and the station's atmosphere was much improved by the end of the decade.[27]

Following the privatisation of British Rail in 1996, express services into the station were taken over by the Great North Eastern Railway (GNER). The company refurbished the British Rail Mark 4 "Mallard" rolling stock used for long-distances services from King's Cross and the inauguration of the new-look trains took place in the presence of the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh in 2003.[49]

GNER successfully re-bid for the franchise in 2005 but surrendered it the following year.[50] National Express East Coast took over the franchise in late 2007 after an interim period when trains ran under a management contract.[51] In 2009, it was announced that National Express was no longer willing to finance the East Coast subsidiary and the franchise was taken back into public ownership and handed over to East Coast in November.[52]

Restoration

The £500 million restoration plan announced by Network Rail in 2005 was approved by Camden London Borough Council in 2007.[54] It involved restoring and reglazing the original arched train shed roof and removing the 1972 extension at the front of the station and replacing it with an open-air plaza.[53][55]

The new semi-circular departures concourse opened to the public in March 2012.[56][57] Situated to the west of the station behind the Great Northern Hotel, it was designed by John McAslan and built by Vinci.[58] It caters for much-increased passenger flows and provides greater integration between the intercity, suburban and underground sections of the station. The architect claimed that the roof is the longest single-span station structure in Europe and the semi-circular structure has a radius of 59 yards (54 m) and more than 2,000 triangular roof panels, half of which are glass.[53]

Land between and behind Kings Cross and St Pancras stations is being redeveloped as King's Cross Central with around 2,000 new homes, 5,000,000 sq ft (464,500 m2) of offices and new roads.[59] In the restoration, refurbished offices have opened on the east side of the station to replace ones lost on the west side, and a new platform, numbered 0, opened underneath them on 20 May 2010.[60] Diesel trains cannot normally use this platform for environmental reasons.[61] The restoration project was awarded a European Union Prize for Cultural Heritage / Europa Nostra Award in 2013.[62][63]

In May 2016, the Office of Rail Regulation approved a new operator, East Coast Trains, to operate services to Edinburgh Waverley via Stevenage, Newcastle & Morpeth. The service is expected to start in 2021.[64][65][66]

Accidents and incidents

There have been many accidents at King's Cross over the years. The most serious were the King's Cross railway accident on 4 February 1945 which killed two people and injured 25.[38][39] and a collision in Gasworks tunnel on 15 September 1881 which killed one person and seriously injured another.[29] The most recent was on 17 September 2015 when a passenger train collided with the buffer stops, injuring fourteen people.[67][68]

Other stations

King's Cross York Road

From 1863, part of King's Cross was an intermediate station. On the extreme east of the site, King's Cross York Road station was served by suburban trains from Finsbury before they followed the sharply curved and steeply graded York Road Tunnel to join the City Widened Lines to Farringdon, Barbican and Moorgate. In the other direction, trains from Moorgate came off the Widened Lines via the Hotel Curve,[22] to platform 16 (latterly renumbered 14) which rose to the main line level. Services to and from Moorgate were diverted via the Northern City Line from November 1976. The station remained in occasional use until it was completely closed on 5 March 1977.[69]

Great Northern Cemetery Station

The Great Northern Cemetery Station was built 50 metres (160 ft) to the east of the main station complex[70] to transport coffins and mourners from the city to the burial grounds at New Southgate Cemetery. The station opened in 1861 but was never profitable and closed in 1873.[71]

Services

Great Northern Route | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hull Trains Route | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Grand Central routes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The station hosts services on inter-city routes to the East of England, Yorkshire, North East England and eastern and northern Scotland, connecting to major cities and towns such as Cambridge, Peterborough, Hull, Doncaster, Leeds, York, Sunderland, Newcastle, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Bradford, Aberdeen and Inverness.

Train services

Four train services operate from King's Cross:

Virgin Trains East Coast operates high speed inter-city services along the East Coast Main Line. Basic off-peak timetable includes:[73]

- Half-hourly service to Leeds

- 1 train per hour calling at Peterborough, Doncaster and Wakefield Westgate

- 1 train per hour calling at Stevenage, Grantham, Doncaster and Wakefield Westgate

- One service is extended to each of Bradford Forster Square, Skipton and Harrogate per day.

- Hourly semi-fast service to Newcastle Central (extended to Edinburgh every two hours) calling at Peterborough, Newark North Gate, Doncaster, York, Northallerton, Darlington and Durham

- Services at peak hours are extended to Edinburgh Waverley calling at Alnmouth

- One service is extended to each of Glasgow Central via Edinburgh and Sunderland per day.

- Services at peak hours are extended to Edinburgh Waverley calling at Alnmouth

- Hourly express service to Edinburgh Waverley calling at York, Darlington, Newcastle Central and Berwick-upon-Tweed.

- Two-hourly service to Newark North Gate/York calling at all stations on route.

- 1 service extended daily to Newcastle

- 1 service extended daily to Lincoln

Great Northern operates outer-suburban services to North London, Hertfordshire and Cambridgeshire. Basic off-peak timetable includes:[74]

- 2 services per hour to Peterborough (1 semi-fast, 1 stopping)

- 1 service per hour to Ely

- 1 service per hour to King's Lynn

- 1 stopping service per hour to Cambridge North

- 1 semi-fast service per hour to Cambridge

Hull Trains operates daily inter-city services to Hull and a limited weekday service to Beverley via the East Coast Main Line. Unlike other train companies in FirstGroup, Hull Trains operates under an open-access arrangement and is not a franchised train operating company.[75]

Grand Central operates inter-city services to Bradford and Sunderland along the East Coast Main Line and is an open-access operator. On 23 May 2010 it began services to Bradford Interchange via Halifax, Brighouse, Mirfield, Wakefield, Pontefract and Doncaster[76] which had originally been due to begin in December 2009.[77][78]

Routes

| Preceding station | |

Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terminus | Hull Trains London-Hull |

Stevenage or Grantham | ||

| Terminus | Hull Trains London-Beverley |

Grantham | ||

| Terminus | Virgin Trains East Coast London-Leeds |

Stevenage or Peterborough | ||

| Terminus | Virgin Trains East Coast The Flying Scotsman |

Newcastle Central | ||

| Terminus | Virgin Trains East Coast London-Edinburgh fast |

Peterborough or York | ||

| Terminus | Virgin Trains East Coast London-Newcastle/Edinburgh semi-fast |

Stevenage or Peterborough or York | ||

| Terminus | Virgin Trains East Coast London-Lincoln/York |

Stevenage or Peterborough | ||

| Terminus | Virgin Trains East Coast London-Hull One train a day |

Selby or Peterborough or Stevenage | ||

| Terminus | Grand Central North Eastern London-Sunderland |

York | ||

| Grand Central West Riding London-Bradford Interchange |

Doncaster | |||

| Terminus | Great Northern Cambridge Cruiser and London-Cambridge (Semi-fast) |

Cambridge or Finsbury Park or Letchworth Garden City or Royston | ||

| Terminus | Great Northern London-Peterborough |

Finsbury Park or Stevenage or Hitchin or Biggleswade or St. Neots or Huntingdon | ||

| Terminus | Great Northern Suburban services (Peak times only) |

Finsbury Park | ||

| Disused railways | ||||

| Finsbury Park | British Rail Eastern Region City Widened Lines |

Farringdon via King's Cross York Road | ||

| Historical railways | ||||

| Terminus | Great Northern Railway East Coast Main Line |

Holloway & Caledonian Road Line open, station closed | ||

Tube station

King's Cross St. Pancras tube station is served by more lines than any other station on the London Underground. In 2005, it was the busiest tube station, but has been overtaken by others since.[79] It is in Travelcard Zone 1 and caters for both Kings Cross and the neighbouring St. Pancras railway station.

The station opened as part of the first section of Metropolitan Railway project on 10 January 1863; the first part of the Underground to open.[80] It was expanded to accommodate the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway (now the Piccadilly line) in 1906,[81] with the City & South London Railway (now the Northern line) opening a year later.[82]

The Victoria line platforms were opened in 1968.[83] A major expansion to accommodate High Speed 1 at St. Pancras opened in November 2009.[84]

Cultural references

In fiction

The station is mentioned in Chapter 2 of E.M. Forster's 1910 novel Howards End, where it suggests "infinity" to the eldest Schlegel daughter, Margaret, and contrasted with the "facile splendours" of St. Pancras.[85]

King's Cross features in the Harry Potter books, by J. K. Rowling, as the starting point of the Hogwarts Express. The train uses a secret Platform 9¾ accessed through the brick wall barrier between platforms 9 and 10.[86] In fact, platforms 9 and 10 are in a separate building from the main station and are separated by two intervening tracks.[87]

Within King's Cross, a cast-iron "Platform 9¾" plaque was erected in 1999, initially in a passageway connecting the main station to the platform 9–11 annexe. Part of a luggage trolley was installed below the sign: the near end of the trolley was visible, but the rest had disappeared into the wall. The location quickly became a popular tourist spot amongst Harry Potter fans.[88] The sign and a revamped trolley, complete with luggage and bird cage, were relocated in 2012, following the development of the new concourse building, and are now sited next to a Harry Potter merchandise shop. Because of the restrained facade of the real King's Cross station, the Harry Potter films showed St. Pancras in exterior station shots instead.[88]

In film

The station, its surrounding streets and the railway approach feature prominently in the 1955 Ealing comedy film The Ladykillers.[89] In the story, a gang robs a security van near the station after planning in a house overlooking the railway. When they fall out, members of the gang are dropped into passing goods wagons from the parapet of the Copenhagen Tunnel north of the station.[90]

The 1986 crime drama film Mona Lisa is set around King's Cross. At the time, the downmarket and seedy area surrounding the station, coupled with urban decay, made it an ideal location. Subsequent early 1990s tabloid coverage of crime and prostitution around King's Cross referred back to the film.[91]

Pet Shop Boys released a song titled "King's Cross" on the 1987 album Actually and the station was extensively filmed in for the group's 1988 feature film It Couldn't Happen Here. The band's Neil Tennant explained that the station was a recognisable landmark coming into London, attempting to find opportunities away from the high unemployment areas of Northeast England at the time. The song was primarily about "hopes being dashed" and "an epic nightmare".[92] The group subsequently asked filmmaker Derek Jarman to direct a background video for "King's Cross" for their 1989 tour, which featured a black and white sequence of juddery camera movements around the local area.[93]

Monopoly

King's Cross station is a square on the British Monopoly board. The other three stations in the game are Marylebone, Fenchurch Street and Liverpool Street, and all four were LNER termini at the time the game was being designed for the British market in the mid-1930s.[94]

References

Notes

- ↑ Lewis Cubitt was also responsible for the design of the Great Northern Hotel (see below).

Citations

- ↑ "Out of Station Interchanges" (XLS). Transport for London. May 2011. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Station usage estimates". Rail statistics. Office of Rail Regulation. Please note: Some methodology may vary year on year.

- ↑ "King's Cross Station". Google Maps. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ↑ "Central London Bus Map" (PDF). Transport for London. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ↑ "King's Cross". Network Rail. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ↑ Badsey-Ellis, Antony (November 2008). "The Underground and the apostrophe" (PDF). Underground News. London Underground Railway Society. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ "National Rail station codes CSV". Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ Walter H Godfrey; W McB. Marcham, eds. (1952). Battle Bridge Estate. Survey of London. 24, the Parish of St Pancras Part 4: King's Cross Neighbourhood. London. pp. 102–113. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- 1 2 "Dig uncovers Boudicca's brutal streak". The Observer. 3 December 2000. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ↑ "Historical Notes: Boadicea's bones under Platform 10". The Independent. 14 July 1999. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ↑ Johnson, Marguerite (2012). Boudicca. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-853-99732-7.

- 1 2 3 Weinreb et al. 2010, p. 463.

- 1 2 Jackson 1984, p. 76.

- ↑ Thornbury, Walter (1878). "Highbury, Upper Holloway and King's Cross". Old and New London. London. 2: 273–279. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ↑ Butt, R.V.J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations. Yeovil: Patrick Stephens. p. 134. ISBN 1-85260-508-1. R508.

- ↑ Diaries of George Turnbull (Chief Engineer, East Indian Railway Company) held at the Centre of South Asian Studies at Cambridge University, England.

- ↑ Page 87 of George Turnbull, C.E. 437-page memoirs published privately 1893, scanned copy held in the British Library, London on compact disk since 2007.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, p. 77.

- ↑ Young, John (1977). Great Northern suburban. David & Charles. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-715-37477-1.

- ↑ "History – King's Cross station". Network Rail. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- 1 2 Jackson 1984, p. 78.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, pp. 78–79.

- 1 2 Jackson 1984, p. 79.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, p. 80.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, p. 84.

- 1 2 3 Simmons & Biddle 1997, p. 290.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, pp. 81,83.

- 1 2 "Inquests". The Times (30305). London. 21 September 1881. col D, p. 10.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, p. 83.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, p. 87-8.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, p. 89.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, p. 88.

- ↑ Christopher 2013, p. 47.

- ↑ Sharpe 2009, p. 73.

- ↑ Sharpe 2009, p. 57.

- 1 2 Jackson 1984, p. 90.

- 1 2 "Report on the Accident at King's Cross on 4th February 1945". Railways Archive. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- 1 2 Jackson 1984, p. 93.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, pp. 348–349.

- ↑ Gourvish & Anson 2004, p. 93.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, p. 91.

- ↑ Historic England. "Kings Cross Station (Grade I) (1078328)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Johnson, Marc (12 November 2012). "King's Cross 'temporary' extension torn down after 40 years". Rail.co. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ "King's Cross Square opens to the public". BBC News. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ "On This Day: 10 September 1973: Bomb blasts rock Central London". BBC News. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, p. 350.

- ↑ "On This Day: 18 November 1987 : King's Cross station fire 'kills 27'". BBC News. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ Memorandum by Great North Eastern Railway (GNER) (FOR 115) (Report). GNER. October 2003. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ↑ "GNER to surrender top train route". BBC News. 15 December 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ↑ "National Express wins rail route". BBC News. 14 August 2007. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ↑ "East Coast rail change confirmed". BBC News. 5 November 2009.

- 1 2 3 Long, Kieran (14 March 2012). "All change at King's Cross". London Evening Standard. p. 34.

- ↑ "Planning Application – 2006/3387/P". London Borough of Camden. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ↑ "Network Rail unveils look for King's Cross square". Rail. Peterborough. 10 August 2011. p. 14.

- ↑ Silvester, Katie (14 March 2012). "New concourse set to open at King's Cross". Rail Professional.

- ↑ "What's changing at King's Cross?". Network Rail. 2012.

- ↑ "London King's Cross western concourse opens". Railway Gazette International. London. 19 March 2012.

- ↑ "Kings Cross place plan". London Borough of Camden. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ↑ "Zero Hour for King's Cross as transport Secretary Opens New Platform 0". Network Rail. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ↑ Marsh, Phil (July 2010). Pigott, Nick, ed. "King's Cross Platform Zero opens". The Railway Magazine. London. 156 (1311): 7. ISSN 0033-8923.

- ↑ "Awards". Europa Nostra.

- ↑ "Winners of 2013 EU Prize for Cultural Heritage / Europa Nostra Awards announced" (Press release). European Commission.

- ↑ Applications for the East Coast Main Line Office of Rail and Road 12 May 2016

- ↑ First Group to run Edinburgh to London budget rail service BBC News 12 May 2016

- ↑ VTEC and FirstGroup granted East Coast Main Line paths Railway Gazette International 12 May 2016

- ↑ "Govia Thameslink King's Cross rail crash: Five hurt". BBC News. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ "Collision with buffer stops at King's Cross 17 September 2015" (PDF). Rail Accident Investigation Branch. 4 August 2016.

- ↑ Jackson 1984, p. 348.

- ↑ Compliance Report : Landscape Details for the Podium Garden, Northern and Southern Gateways & York Way (PDF) (Report). London Borough of Islington Council. September 2016. p. 3. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ↑ "The dead bodies service from King’s Cross railway station". Ian Visits. 19 March 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ↑

- ↑ "Virgin Trains East Coast timetable" (PDF). Virgin Trains. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ↑ "Latest train timetables". First Capital Connect. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "London King's Cross Station". Hull Trains. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ↑ "Grand Central launches West Riding service". Modern Railways. London. June 2010. p. 7.

- ↑ Drury, Colin (19 August 2009). "London rail link blow: Service will be delayed until May". Halifax Evening Courier. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ↑ "Next stop – Mirfield". York: Grand Central. 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "London Underground: 150 fascinating Tube facts". The Daily Telegraph. 9 January 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Wolmar 2004, p. 181.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2008, p. 47.

- ↑ Menear 1983, p. 112.

- ↑ "King's Cross St. Pancras Tube station doubles in size as state-of-the-art ticket hall opens". Transport for London. 27 November 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ↑ "E.M. Forster's draft of Howards End". British Library. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ↑ "Platform 9¾ at King's Cross Station". King's Cross (official website). Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ↑ "King's Cross – Station Guide" (PDF). Network Rail. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- 1 2 "London's 18 Most Magical Harry Potter Sites". MSN. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017.

- ↑ Martin, Andrew (2014). Belles and Whistles: Journeys Through Time on Britain's Trains. Profile Books. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-782-83025-2.

- ↑ Glinert, Ed (2012). The London Compendium. Penguin. p. 882. ISBN 978-0-718-19204-4.

- ↑ Campkin 2013, p. 112.

- ↑ Campkin 2013, p. 84.

- ↑ Campkin 2013, p. 85.

- ↑ Moore 2003, p. 159.

Sources

- "Stations Run by Network Rail". Network Rail. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- "London Kings Cross (KGX)". National Rail Enquiries. National Rail. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- Campkin, Ben (2013). Remaking London: Decline and Regeneration in Urban Culture. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-857-73416-7.

- Christopher, John (2013). King's Cross Station Through Time. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-445-62359-7.

- Day, John R.; Reed, John (2008) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground (10th ed.). Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-316-7.

- Gourvish, Terry; Anson, Mike (2004). British Rail 1974–1997 : From Integration to Privatisation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19926-909-9.

- Jackson, Alan A. (1984) [1969]. London's Termini. London: David & Charles. ISBN 0-330-02747-6.

- Menear, Laurence (1983). London's underground stations: a social and architectural study. Midas. ISBN 978-0-859-36124-8.

- Moore, Tim (2003). Do Not Pass Go. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-099-43386-6.

- Sharpe, Brian (2009). The Flying Scotsman: The Legend Lives on. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-845-63090-4.

- Simmons, Jack; Biddle, Gordon (1997). The Oxford Companion to British Railway History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-019-211697-0.

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, Julia; Keay, John (2010). The London Encyclopedia. Pan MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-4050-4924-5.

- Wolmar, Christian (2004). The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground Was Built and How It Changed the City Forever. Atlantic Books. ISBN 1-84354-023-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to London King's Cross railway station. |

- History of Kings Cross, at the LNER Encyclopedia

- Pictures of the new concourse opened in March 2012 (London Evening Standard website)

Video links

- 1935, Demonstration run of 'Silver Jubilee' to Grantham

- 1944, Retirement of driver Duddington

- 1938, Stirling Single special train