Khudabadi script

| Khudabadi | |

|---|---|

The word "Sindhi" written in the Khudabadi script | |

| Type | |

| Languages | Sindhi language |

Time period | c. 16th century–present |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | Gurumukhi[1] |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 |

Sind, 318 |

Unicode alias | Khudawadi |

| U+112B0–U+112FF | |

|

[a] The Semitic origin of the Brahmic scripts is not universally agreed upon. | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmic script and its descendants |

|

Northern Brahmic

|

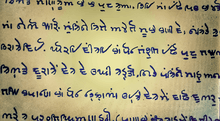

Khudabadi is a script generally used by some Sindhis in India to write the Sindhi language. It is also known as Vaniki, Hatvaniki and Hatkai script. Khudabadi is one of the three scripts used for writing the Sindhi language, the other being Perso-Arabic and Devanagari script.[2] It was used by traders and merchants to record their information and rose to importance as the script began to be used to record information kept secret from other groups and kingdoms.

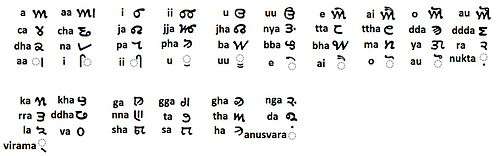

Modern Khudabadi has 37 consonants, 10 vowels, 9 vowel signs written as diacritic marks added to the consonants, 3 miscellaneous signs, one symbol for nasal sounds (anusvara), one symbol for conjucts (virama) and 10 digits like many other Indic scripts. The nukta has been borrowed from Devanagari for representing additional signs found in Arabic but not found in Sindhi. It is written from left to right, like Sanskrit. It follows a natural pattern and style of other Landa scripts.

Origins

The Khudabadi script has roots in the Brahmi script, like most north Indian and West Chinese languages.[3] It appears different from other Indic scripts such as Bengali, Odia, Gurmukhi or Devanagari, but a closer examination reveals they are similar except for angles and structure.[4]

Khudabadi is an abugida in which all consonants have an inherent vowel. Matras are used to change the inherent vowel. Vowels that appear at the beginning of a word are written as independent letters. When certain consonants occur together, special conjunct symbols are used which combine the essential parts of each letter.

The Khudabadi script was created by the Sindhi diaspora residing in Khudabad to send written messages to their relatives, who lived in their hometowns. Due to its simplicity, the use of this script spread very quickly and got acceptance in other Sindhi groups for sending written letters and messages. It continued to be in use for very long period of time. Because it was originated from Khudabad, it was called Khudabadi script.[5]

The Sindhi traders started maintaining their accounts and other business books in this new script. The knowledge of Khudabadi script became important for employing people who intend to go to overseas so that their business accounts and books can be kept secret from foreign people and government officials. Schools started teaching the Sindhi language in Khudabadi script.[6]

Sindhi language is now generally written in the Arabic script, but it belongs to the Indo-Aryan language family and over seventy percent of Sindhi words are of Sanskrit origin.[7] The historian Al-Biruni found Sindhi written in three scripts – Ardhanagari, Mahajani and Khudabadi, all of them variations of Devanagari.[8]

After Mir Nasir Khan Talpur's defeat, British rule commenced in Sindh. When the British arrived they found the Pandits writing Sindhi in Devanagari, Hindu women using Gurmukhi, government servants using Perso-Arabic script and traders keeping their business records in Khudabadi which was completely unknown to the British at the time. The British called it 'Hindu Sindhi' to differentiate it from Sindhi written in the Perso-Arabic script.

The British scholars found the Sindhi language to be closer to Sanskrit and said that the Devanagari script would be suitable for it while the government servants favoured the Arabic script since they did not know Devanagari and had to learn it. A debate began, with Captain Richard Francis Burton favoring the Arabic script and Captain Stack favouring Devanagari.[9]

Sir Bartle Frere, the Commissioner of Sindh, then referred the matter to the Court of Directors of the British East India Company, which directed that:

- The Sindhi Language in Arabic Script to be used for government office use, on the ground that Muslim names could not be written in Devanagari.

- The Education Department should give the instructions to the schools in the script of Sindhi which can meet the circumstance and prejudices of the Mohammadan and Hindu. It is thought necessary to have Arabic Sindhi Schools for Muslims where the Arabic Script will be employed for teaching and to have Hindu Sindhi Schools for Hindus where the Khudabadi Script will be employed for teaching.

In the year 1868, the Bombay Presidency assigned Narayan Jagannath Vaidya (Deputy Educational Inspector of Sindh) to replace the Abjad script used for Sindhi with the Khudabadi script. The script was decreed a standard script modified with ten vowels by the Bombay Presidency.[10] The Khudabadi script of Sindhi language did not make further progress. Traders continued to maintain their records in this script till the independence of Pakistan in 1947.

The present script predominantly used in Sindh as well as in many states in India and else, where migrants Hindu Sindhi have settled, is Arabic in Naskh styles having 52 letters. However, in some circles in India, Khudabadi and Devanagari is used for writing Sindhi. The Government of India recognizes both scripts.[9]

Alphabet

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ə | a | ɪ | i | ʊ | uː | e | ɛ | o | ɔ |

| |

|

|

|

| |||||

| k | kʰ | ɡ | ɠ | ɡʱ | ŋ | ||||

| |

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| c | cʰ | ɟ | ʄ | ɟʱ | ɲ | ||||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

| ʈ | ʈʰ | ɖ | ɗ | ɽ | ṛ | ɳ | |||

| |

|

|

|

| |||||

| t | tʰ | d | dʱ | n | |||||

| |

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| p | pʰ | f | b | ɓ | bʱ | m | |||

| |

|

|

|

||||||

| j | r | l | ʋ | ||||||

| |

|

|

|||||||

| ʃ | s | h | |||||||

Unicode

Khudabadi script was added to the Unicode Standard in June 2014 with the release of version 7.0.

Khudabadi is being used as the unified encoding for all of the Sindhi scripts except for Khojki, because each Sindhi script is named after the mercantile village in which it was used, and a vast majority are not well-developed enough to be encoded. Local scripts may be encoded in the future, but at the present, Khudabadi is recommended to represent all of the Landa-based Sindhi scripts that have been in use.

The Unicode block for Khudabadi, called Khudawadi, is U+112B0–U+112FF:

| Khudawadi[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+112Bx | 𑊰 | 𑊱 | 𑊲 | 𑊳 | 𑊴 | 𑊵 | 𑊶 | 𑊷 | 𑊸 | 𑊹 | 𑊺 | 𑊻 | 𑊼 | 𑊽 | 𑊾 | 𑊿 |

| U+112Cx | 𑋀 | 𑋁 | 𑋂 | 𑋃 | 𑋄 | 𑋅 | 𑋆 | 𑋇 | 𑋈 | 𑋉 | 𑋊 | 𑋋 | 𑋌 | 𑋍 | 𑋎 | 𑋏 |

| U+112Dx | 𑋐 | 𑋑 | 𑋒 | 𑋓 | 𑋔 | 𑋕 | 𑋖 | 𑋗 | 𑋘 | 𑋙 | 𑋚 | 𑋛 | 𑋜 | 𑋝 | 𑋞 | 𑋟 |

| U+112Ex | 𑋠 | 𑋡 | 𑋢 | 𑋣 | 𑋤 | 𑋥 | 𑋦 | 𑋧 | 𑋨 | 𑋩 | 𑋪 | |||||

| U+112Fx | 𑋰 | 𑋱 | 𑋲 | 𑋳 | 𑋴 | 𑋵 | 𑋶 | 𑋷 | 𑋸 | 𑋹 | ||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.ancientscripts.com/landa.html

- ↑ Azimusshan Haider (1974). History of Karachi. Haider. p. 23. OCLC 1604024.

- ↑ Danesh Jain; George Cardona (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 94–99, 72–73. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- ↑ George Cardona and Danesh Jain (2003), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415772945, pages 72-74

- ↑ https://books.google.ae/books/download/Incredible_Origin_and_History_of_Khudaba.enw?id=ihcAmwEACAAJ&output=enw The Incredible History and Origin of Khudabad

- ↑ Dhirendra Narain (2007). Research in Sociology. Concept Publicstion. p. 106.

- ↑ http://www.indianmirror.com/languages/sindhi-language.html Sindhi language

- ↑ https://hindusofsindh.wordpress.com/tag/khudabadi/

- 1 2 "Sindhi Language: Script". Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ "Omniglot: Sindhi alphabets, pronunciation and language". Retrieved 15 May 2012.