Quipu

| Queipu, Khipo | |

|---|---|

| Type |

other

|

| Languages | Aymara, Quechua, Puquina languina |

Time period | 5rd millennium BCEA – 17th century (some variants are used today) |

Sister systems | Chinese knots, Wampum |

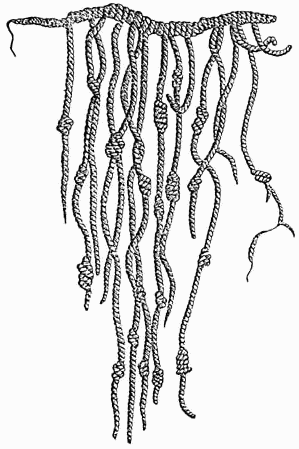

Quipus, also known as khipos or talking knots,[1] were recording devices historically used in a number of cultures and particularly in the region of Andean South America.[2] Similar systems were used by the ancient Chinese and native Hawaiians,[3] though this article specifically deals with the most familiar Inca system, and knotted string records are often generically referred to in English as quipus after the Inca term. A quipu usually consisted of colored, spun, and plied thread or strings made from cotton or camelid fiber. For the Inca, the system aided in collecting data and keeping records, ranging from monitoring tax obligations, properly collecting census records, calendrical information, and military organization.[4] The cords contained numeric and other values encoded by knots in a base ten positional system. A quipu could have only a few or up to 2,000 cords.[5] The configuration of the quipus have also been "compared to string mops."[6] Archaeological evidence has also shown a use of finely carved wood as a supplemental, and perhaps more sturdy, base on which the color-coordinated cords would be attached.[7] A relatively small number have survived.

Objects that can be identified unambiguously as quipus first appear in the archaeological record in the first millennium AD. They subsequently played a key part in the administration of the Kingdom of Cusco and later Tawantinsuyu, the empire controlled by the Incan ethnic group, flourishing across the Andes from c. 1100 to 1532 AD. As the region was subsumed under the invading Spanish Empire, the use of the quipu faded from use, to be replaced by European writing systems. However, in several villages, quipu continued to be important items for the local community, albeit for ritual rather than recording use. It is unclear as to where and how many intact quipus still exist, as many have been stored away in mausoleums, 'along with the dead.'[8]

Quipu is the Spanish spelling and the most common spelling in English. Khipu (pronounced [ˈkʰipu], plural: khipukuna) is the word for "knot" in Cusco Quechua; the kh is an aspirated k. In most Quechua varieties, the term is kipu.

Etymology

The word "khipu", meaning "knot" or "to knot", comes from the Quechua language word: quipu,1704, the "lingua franca and language of administration" of Tawantin Suyu.[9]

Archaeologist Gary Urton, 2003.[10]

Purpose

_p360.png)

Most information recorded on the quipus consists of numbers in a decimal system.[11]

In the early years of the Spanish conquest of Peru, Spanish officials often relied on the quipus to settle disputes over local tribute payments or goods production. Spanish chroniclers also concluded that quipus were used primarily as mnemonic devices to communicate and record numerical information. Quipucamayocs (Quechua khipu kamayuq "khipu specialist", plural: khipu kamayuqkuna) could be summoned to court, where their bookkeeping was recognised as valid documentation of past payments.

Some of the knots, as well as other features, such as color, are thought to represent non-numeric information, which has not been deciphered. It is generally thought that the system did not include phonetic symbols analogous to letters of the alphabet. However Gary Urton has suggested that the quipus used a binary system which could record phonological or logographic data.

To date, no link has yet been found between a quipu and Quechua, the native language of the Peruvian Andes. This suggests that quipus are not a glottographic writing system and have no phonetic referent. Frank Salomon at the University of Wisconsin has argued that quipus are actually a semasiographic language, a system of representative symbols—such as music notation or numerals—that relay information but are not directly related to the speech sounds of a particular language. The Khipu Database Project (KDP), begun by Gary Urton, may have already decoded the first word from a quipu—the name of a village, Puruchuco, which Urton believes was represented by a three-number sequence, similar to a ZIP code. If this conjecture is correct, quipus are the only known example of a complex language recorded in a 3-D system.[12]

System

| Numeral systems |

|---|

|

| Hindu–Arabic numeral system |

| East Asian |

| Alphabetic |

| Former |

| Positional systems by base |

| Non-standard positional numeral systems |

| List of numeral systems |

Marcia and Robert Ascher, after having analyzed several hundred quipus, have shown that most information on quipus is numeric, and these numbers can be read. Each cluster of knots is a digit, and there are three main types of knots: simple overhand knots; "long knots", consisting of an overhand knot with one or more additional turns; and figure-eight knots. In the Aschers’ system, a fourth type of knot—figure-of-eight knot with an extra twist—is referred to as "EE". A number is represented as a sequence of knot clusters in base 10.[13]

- Powers of ten are shown by position along the string, and this position is aligned between successive strands.

- Digits in positions for 10 and higher powers are represented by clusters of simple knots (e.g., 40 is four simple knots in a row in the "tens" position).

- Digits in the "ones" position are represented by long knots (e.g., 4 is a knot with four turns). Because of the way the knots are tied, the digit 1 cannot be shown this way and is represented in this position by a figure-of-eight knot.

- Zero is represented by the absence of a knot in the appropriate position.

- Because the ones digit is shown in a distinctive way, it is clear where a number ends. One strand on a quipu can therefore contain several numbers.

For example, if 4s represents four simple knots, 3L represents a long knot with three turns, E represents a figure-of-eight knot and X represents a space:

- The number 731 would be represented by 7s, 3s, E.

- The number 804 would be represented by 8s, X, 4L.

- The number 107 followed by the number 51 would be represented by 1s, X, 7L, 5s, E.

This reading can be confirmed by a fortunate fact: quipus regularly contain sums in a systematic way. For instance, a cord may contain the sum of the next n cords, and this relationship is repeated throughout the quipu. Sometimes there are sums of sums as well. Such a relationship would be very improbable if the knots were incorrectly read.[5]

Some data items are not numbers but what Ascher and Ascher call number labels. They are still composed of digits, but the resulting number seems to be used as a code, much as we use numbers to identify individuals, places, or things. Lacking the context for individual quipus, it is difficult to guess what any given code might mean. Other aspects of a quipu could have communicated information as well: color-coding, relative placement of cords, spacing, and the structure of cords and sub-cords.[14]

Literary uses

Some have argued that far more than numeric information is present and that quipus are a writing system. This would be an especially important discovery as there is no surviving record of written Quechua predating the Spanish invasion. Possible reasons for this apparent absence of a written language include an actual absence of a written language, destruction by the Spanish of all written records, or the successful concealment by the Incan peoples of those records. Making the matter even more complex, the Inca 'kept separate "khipu" for each province, on which a pendant string recorded the number of people belonging to each category.'[15] This creates yet another step in the process of decryption in addition to the Spanish attempts at eradicating the system. Historians Edward Hyams and George Ordish believe quipus were recording devices, similar to musical notation, in that the notes on the page present basic information, and the performer would then bring those details to life.[16]

In 2003, while checking the geometric signs that appear on drawings of Inca dresses from the First New Chronicle and Good Government, written by Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala in 1615, William Burns Glynn found a pattern that seems to decipher some words from quipus by matching knots to colors of strings.

The August 12, 2005, edition of the journal Science includes a report titled "Khipu Accounting in Ancient Peru" by anthropologist Gary Urton and mathematician Carrie J. Brezine.[17] Their work may represent the first identification of a quipu element for a non-numeric concept, a sequence of three figure-of-eight knots at the start of a quipu that seems to be a unique signifier. It could be a toponym for the city of Puruchuco (near Lima), or the name of the quipu keeper who made it, or its subject matter, or even a time designator.

Beynon-Davies considers quipus as a sign system and develops an interpretation of their physical structure in terms of the concept of a data system.[18]

Khipu kamayuqkuna (knot makers/keepers, i.e., the former Inka record keepers) supplied colonial administrators with a variety and quantity of information pertaining to censuses, tribute, ritual and calendrical organization, genealogies, and other such matters from Inka times. Performing a number of statistical tests for quipu sample VA 42527, one study led by Alberto Sáez-Rodríguez discovered that the distribution and patterning of S- and Z-knots can organize the information system from a real star map.

Laura Minelli, a professor of Precolumbian studies at the University of Bologna, has discovered something which she believed to be a seventeenth-century Jesuit manuscript that contains detailed information on literary quipus. This manuscript consists of nine folios with Spanish, Latin, and ciphered Italian texts. Owned by the family of Neapolitan historian Clara Miccinelli, the manuscript also includes a wool quipu fragment. Miccinelli believes that the text was written by two Italian Jesuit missionaries, Joan Antonio Cumis and Giovanni Anello Oliva, around 1610–1638, and Blas Valera, a mestizo Jesuit sometime before 1618. Along with the details of reading literary quipus, the documents also discuss the events and people of the Spanish conquest of Peru.

In the text of these documents, Cumis states that there are quipus which accounted for uses other than accounting. Since so many quipus were burned by the Spanish, very few remained for Cumis to analyze. As related in the manuscript, the word Pacha Kamaq, the Inca deity of earth and time, was used many times in these quipus, where the syllables were represented by symbols formed in the knots. Following the analysis of the use of "Pacha Kamaq", the manuscript offers a list of many words present in quipus. Bruce Mannheim, the director of the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Michigan, and Colgate University's Gary Urton question the location of its origin and its authenticity.[19][20]

History

Tawantin Suyu

Quipucamayocs (Quechua khipu kamayuq, "khipu-authority"), the accountants of Tawantin Suyu, created and deciphered the quipu knots. Quipucamayocs could carry out basic arithmetic operations, such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. They kept track of mita, a form of taxation. The quipucamayocs also tracked the type of labor being performed, maintained a record of economic output, and ran a census that counted everyone from infants to "old blind men over 80". The system was also used to keep track of the calendar. According to Guaman Poma, quipucamayocs could "read" the quipus with their eyes closed.[5]

Quipucamayocs were from a class of people, "males, fifty to sixty",[21] and were not the only members of Inca society to use quipus. Inca historians used quipus when telling the Spanish about Tawantin Suyu history (whether they only recorded important numbers or actually contained the story itself is unknown). Members of the ruling class were usually taught to read quipus in the Inca equivalent of a university, the yachay wasi (literally, "house of teaching"), in the third year of schooling, for the higher classes who would eventually become the bureaucracy.[22]

Spanish invasion

In 1532, the Spanish Empire's conquest of the Andean region began, with several Spanish conquerors making note of the existence of quipus in their written records about the invasion. The earliest known example comes from Hernando Pizarro, the brother of the Spanish military leader Francisco Pizarro, who recorded an encounter that he and his men had in 1533 as they traveled along the royal road from the highlands to the central coast.[14] It was during this journey that they encountered several quipu keepers, later relating that these keepers "untied some of the knots which they had in the deposits section [of the khipu], and they [re-]tied them in another section [of the khipu]."[23]

The Spanish authorities quickly suppressed the use of quipus.[24]

Contemporary social importance

The quipu system operated as both a method of calculation and social organization, regulating regional governance and 'land use.'[25] While evidence for the latter is still under the critical eye of scholars around the world, the very fact that they are kept to this day without any confirmed level of fluent literacy in the system is testament to its historical 'moral authority.'[26] Today, "khipu" is regarded as a powerful symbol of heritage, only 'unfurled' and handled by 'pairs of [contemporary] dignitaries,' as the system and its 'construction embed' modern 'cultural knowledge.'[26] Ceremonies in which they are 'curated, even though they can no longer be read,' is even further support for the case of societal honor and significance associated with the quipu.[26] Even today, 'the knotted cords must be present and displayed when village officers leave or begin service, and draping the cords over the incoming office holders instantiates the moral and political authority of the past.'[26] These examples are indicative of how the quipu system is not only fundamental mathematically or linguistically for the original Inca, but also for the cultural preservation of the original empire's descendants.

Anthropologists and archaeologists working in Peru have highlighted two known cases where quipus have continued to be used by contemporary communities, albeit as ritual items seen as "communal patrimony" rather than as devices for recording information.[27] The Khipu system, being the efficient method of social management it was for the Inca, is also a link to the Cuzco census, as it was one of the primary methods of population calculation.[28] This also has allowed historians and anthropologists to understand both the census and the "decimal hierarchy" system the Inca used, and that they were actually 'initiated together,' due to the fact that they were 'conceptually so closely linked.'[28]

Tupicocha, Peru

In 1994, the American cultural anthropologist Frank Salomon conducted a study in the Peruvian village of Tupicocha, where quipus are still an important part of the social life of the village.[29] As of 1994, this was the only village where quipus with a structure similar to pre-Columbian quipus were still used for official local government record-keeping and functions, although the villagers did not associate their quipus with Inca artifacts.[30]

San Cristóbal de Rapaz, Peru

The villagers of San Cristóbal de Rapaz (known as Rapacinos), located in the Province of Oyón, keep a quipu in an old ceremonial building, the Kaha Wayi, that is itself surrounded by a walled architectural complex. Also within the complex is a disused communal storehouse, known as the Pasa Qullqa, which was formerly used to protect and redistribute the local crops, and some Rapacinos believe that the quipu was once a record of this process of collecting and redistributing food.[14] The entire complex was important to the villagers, being "the seat of traditional control over land use, and the centre of communication with the deified mountains who control weather".[27]

In 2004, the archaeologist Renata Peeters (of the UCL Institute of Archaeology in London) and the cultural anthropologist Frank Salomon (of the University of Wisconsin) undertook a project to conserve both the quipus in Rapaz and the building that it was in, due to their increasingly poor condition.[31]

Archaeological investigation

The archaeologist Gary Urton noted in his 2003 book Signs of the Inka Khipu that he estimated "from my own studies and from the published works of other scholars that there are about 600 extant quipu in public and private collections around the world."[32]

According to the Khipu Database Project[33] undertaken by Harvard professor Gary Urton and his colleague Carrie Brezine, 751 quipus have been reported to exist across the globe. Their whereabouts range from Europe to North and South America. Most are housed in museums outside of their native countries, however some reside in their native locations under the care of the descendants of those who made the knot records. A table of the largest collections is shown below.

| Museum Collection | Location | Quipus |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnological Museum of Berlin | Berlin, Germany | 298 |

| Museum Five Continents[34] | Munich, Germany | |

| Pachacamac[35] | near Lima, Peru | 35 |

| Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú[36] | Lima, Peru | 35 |

| Centro Mallqui[37] | Leimebamba, Amazonas, Peru | 32 |

| Museo Temple Radicati, National University of San Marcos | Lima, Peru | 26 |

| Museo Regional de Ica | Ica, Peru | 25 |

| Museo Puruchuco[38] | Ate District, Lima, Peru | 23 |

While patrimonial quipu collections have not been accounted for in this database, their numbers are likely to be unknown. One prominent patrimonial collection held by the Rapazians of Rapaz, Peru, was recently researched by University of Wisconsin–Madison professor, Frank Salomon. The Anthropology/Archaeology department at the University of California at Santa Barbara also holds one quipu.

Preservation

Quipus are now preserved using techniques that will minimise their future degradation. Museums, archives and special collections have adopted preservation guidelines from textile practices. Quipus are made of fibers, either spun and plied thread such as wool or hair from alpaca, llama, guanaco or vicuña, though are also commonly made of cellulose like cotton. The knotted strings of quipus were often made with an "elaborate system of knotted cords, dyed in various colors, the significance of which was known to the magistrates".[39] Fading of color, natural or dyed, cannot be reversed, and may indicate further damage to the fibers. Colors can darken if attacked by dust or by certain dyes and mordants. Quipus have been found with adornments, such as animal shells, attached to the cords, and these non-textile materials may require additional preservation measures.

All textiles are damaged by ultraviolet (UV) light. This damage can include fading and weakening of the fibrous material. Environmental controls are used to monitor and control temperature, humidity and light exposure of storage areas. The heating, ventilating and air conditioning, or HVAC systems, of buildings that house quipu knot records are usually automatically regulated. Relative humidity should be 60% or lower, with low temperatures. High temperatures can damage the fibres and make them brittle. Damp conditions and high humidity can damage protein-rich material. As with all textiles, cool, clean, dry and dark environments are most suitable. When quipus are on display, their exposure to ambient conditions is usually minimized and closely monitored.[40]

Quipus are also closely monitored for mold, as well as insects and their larvae. As with all textiles, these are major problems. Fumigation may not be recommended for fiber textiles displaying mold or insect infestations, although it is common practice for ridding paper of mold and insects.

Damage can occur during storage. The more accessible the items are during storage, the greater the chance of early detection.[40] Storing quipus horizontally on boards covered with a neutral pH paper (paper that is neither acid or alkaline) to prevent potential acid transfer is a preservation technique that extends the life of a collection. Extensive handling of quipus can also increase the risk of further damage. The fibers can be abraded by rubbing against each other or for those attached to sticks or rods by their own weight if held in an upright position.[41]

When Gary Urton, professor of Anthropology at Harvard, was asked "Are they [quipus] fragile?", he answered, "some of them are, and you can't touch them – they would break or turn into dust. Many are quite well preserved, and you can actually study them without doing them any harm. Of course, any time you touch an ancient fabric like that, you're doing some damage, but these strings are generally quite durable."[42]

Ruth Shady, a Peruvian archeologist, has discovered a quipu or perhaps proto-quipu believed to be around 5,000 years old in the coastal city of Caral. It was in quite good condition, with "brown cotton strings wound around thin sticks", along with "a series of offerings, including mysterious fiber balls of different sizes wrapped in 'nets' and pristine reed baskets. Piles of raw cotton – uncombed and containing seeds, though turned a dirty brown by the ages – and a ball of cotton thread" were also found preserved. The good condition of these articles can be attributed to the arid condition of Caral.[43]

Even when people have tried to preserve quipus, corrective care may still be required. Conservators in the field of library science have the skills to handle a variety of situations. If quipus are to be conserved close to their place of origin, local camelid or wool fibres in natural colors can be obtained and used to mend breaks and splits in the cords.[44] Even though some quipus have hundreds of cords, each cord should be assessed and treated individually. Quipu cords can be "mechanically cleaned with brushes, small tools and light vacuuming".[44] Just as the application of fungicides is not recommended to rid quipus of mold, neither is the use of solvents to clean them. Rosa Choque Gonzales and Rosalia Choque Gonzales, conservators from southern Peru, worked to conserve the Rapaz patrimonial quipus in the Andean village of Rapaz, Peru. These quipus had undergone repair in the past, so this conservator team used new local camelid and wool fibers to spin around the area under repair in a similar fashion to the earlier repairs found on the quipu.[44]

See also

- Caral, site of discovery of a "proto-quipu" (ca. 3000 BC)

- Wampum, North American beads used as memory aids

- Yupana, an Incan calculating device

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Domenici, Viviano; Domenici, Davide (1996). "Talking Knots of the Inka". Archaeology. 49 (6). Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ↑ Neuman, William (January 2, 2016). "Untangling an Accounting Tool and an Ancient Incan Mystery". New York Times. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ↑ Jacobsen, Lyle E. "Use of Knotted String Accounting Records in Old Hawaii and Ancient China". Accounting Historians Journal. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ D'altroy, Terence N. (2001). 18

- 1 2 3 "Quipu" 2012, http://www.ancientscripts.com/quipu.html

- ↑ Urton, Gary, Carrie Brezine. Harvard University. (2009)

- ↑ D'altroy, Terence N. (2001). 16–17

- ↑ Urton, Gary. (2011). "Tying the Archive in Knots, or: Dying to Get into the Archive in Ancient Peru

- ↑ Urton 2003. p. 1.

- ↑ Urton 2003. pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Ordish, George; Hyams, Edward (1996). The last of the Incas: the rise and fall of an American empire. New York: Barnes & Noble. p. 80. ISBN 0-88029-595-3.

- ↑ Adams, Mark (July 12, 2011) "Questioning the Inca Paradox: Did the civilization behind Machu Picchu really fail to develop a written language?"

- ↑ "Quipu" (2012)

- 1 2 3 Locke, 1912

- ↑ D'altroy, Terrence N. "The Incas." 234–235

- ↑ Ordish, George; Hyams, Edward (1996). The last of the Incas: the rise and fall of an American empire. New York: Barnes & Noble. p. 84. ISBN 0-88029-595-3.

- ↑ Urton, Gary; Brezine, Carrie J. (12 August 2005). "Khipu Accounting in Ancient Peru". Science. 309 (5737): 1065–1067. PMID 16099983. doi:10.1126/science.1113426.

- ↑ Beynon-Davies, P (2009). "Significant threads: the nature of data". International Journal of Information Management. 29 (3): 170–188. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2008.12.003.

- ↑ Domenici, Viviano and Davide, 1996

- ↑ (2012) "Quipu" 2012, http://www.ancientscripts.com/quipu.html

- ↑ Ordish, George; Hyams, Edward (1996). The last of the Incas: the rise and fall of an American empire. New York: Barnes & Noble. p. 69. ISBN 0-88029-595-3.

- ↑ Ordish, George; Hyams, Edward (1996). The last of the Incas: the rise and fall of an American empire. New York: Barnes & Noble. p. 113. ISBN 0-88029-595-3.

- ↑ Urton 2003. p. 3.

- ↑ "Fernando Murillo de la Serda. Carta sobre los caracteres, 1589". Archived from the original on 28 June 2012.

- ↑ Niles, Susan A. (2007). Considering Quipus: Andean Knotted String Records in Analytical Context. 92–93

- 1 2 3 4 Niles, Susan A. (2007). 93

- 1 2 Peters and Salomon 2006/2007. p. 41.

- 1 2 D'Altroy, Terence N. (2001). 234–235

- ↑ Domenici, 1996

- ↑ Salomon 2004

- ↑ Peters and Salomon 2006/2007. pp. 41–44.

- ↑ Urton 2003. p. 2.

- ↑ "Khipu Database Project".

- ↑ "State Museum of Ethnography".

- ↑ "Museo de Pachacamac".

- ↑ "Museo Nacional de Arqueologia, Antropologia e Historia".

- ↑ "Centro Mallqui Cultura".

- ↑ "Museo Puruchuco".

- ↑ Bingham, Hiram (1948). Lost City of the Incas, The Story of Machu Picchu and its Builders’.. New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce. OCLC 486224.

- 1 2 "Conservation Register".

- ↑ Piechota, Dennis (1978). "Storage Containerization Archaeological Textile Collections". Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. 18 (1): 10–18. JSTOR 3179387. doi:10.2307/3179387.

- ↑ "Conversations String Theorist".

- ↑ Mann, Charles (2005). "Unraveling Khipu's Secrets". Science. 309 (5737): 1008–1009. PMID 16099962. doi:10.1126/science.309.5737.1008. "proto-quipu" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 Salomon, Frank; Peters,, Renata (2007). Governance and Conservation of the Rapaz Khipu Patrimony.. Archaeology International #10.

Bibliography

- Adrien, Kenneth (2001). Andean Worlds: Indigenous History, Culture and Consciousness. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-2359-6.

- The Archaeological Institute of America (November–December 2005). "Conversations: String Theorist". Archaeology. 58 (6). ISSN 0003-8113.

- Ascher, Marcia; Robert Ascher (1978). Code of the Quipu: Databook. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ASIN B0006X3SV4.

- Ascher, Marcia; Robert Ascher (1980). Code of the Quipu: A Study in Media, Mathematics, and Culture. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-09325-8.

- Brokaw, Galen (2010). A History of the Khipu. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521197793.

- Cook, Gareth (January 2007). "Untangling the Mystery of the Inca". Wired (15.01). ISSN 1059-1028.

- D'Altroy, Terrence N. (2001). The Incas. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-17677-0.

- Day, Cyrus Lawrence (1967). Quipus and witches' knots; the role of the knot in primitive and ancient cultures. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press. OCLC 1446690.

- Hyland, Sabine. 2017. Writing with Twisted Cords: The Inscriptive Capacity of Andean Khipus. Current Anthropology 58(3). Web access

- Niles, Susan A. (2007). "Considering Quipus: Andean Knotted String Records in Analytical Context". Taylor and Francis. ISSN 0093-8157.

- Nordenskiold, Erland (1925). The Secret of the Peruvian Quipus. OCLC 2887018.

- Peters, Renata; Salomon, Frank (2006–2007). "Patrimony and partnership: conserving the khipu legacy of Rapaz, Peru". Archaeology International. London: UCL Institute of Archaeology. pp. 41–44. ISSN 1463-1725.

- Piechota, Dennis (1978). "Storage Containerization Archaeological Textile Collections". Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. 18 (1): 10–18. JSTOR 3179387. doi:10.2307/3179387.

- Saez-Rodríguez, A. (2012). An Ethnomathematics Exercise for Analyzing a Khipu Sample from Pachacamac (Perú). Revista Latinoamericana de Etnomatemática. 5(1), 62–88.

- Salomon, Frank (2001). "How an Andean 'Writing Without Words' Works". Current Anthropology. 42 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1086/318435.

- Salomon, Frank (2004). The Cord Keepers: Khipus and Cultural Life in a Peruvian Village. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3379-1. OCLC 54929904.

- Salomon, Frank & Renata Peters (31 March 2007). "Governance and Conservation of the Rapaz Khipu Patrimony" (with collaboration of Carrie Brezine, Gino de las Casas Ríos, Víctor Falcón Huayta, Rosa Choque Gonzales, and Rosalía Choque Gonzales). paper delivered at Interdisciplinary Workshop on Intangible Heritage. Collaborative for Cultural Heritage and Museum Practices, Urbana-Champaign, IL.

- Urton, Gary (1998). "From Knots to Narratives: Reconstructing the Art of Historical Record Keeping in the Andes from Spanish Transcriptions of Inka Khipus". Ethnohistory. 45 (5): 409–438. JSTOR 483319. doi:10.2307/483319.

- Urton, Gary (2003). Signs of the Inka Khipu: Binary Coding in the Andean Knotted-String Records. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-78539-9. OCLC 50323023.

- Urton, Gary; Carrie Brezine (2003–2004). "The Khipu Database Project". Archived from the original on April 27, 2006.

- Urton, Gary (2011). "Tying the Archive in Knots, or: Dying to get into the Archive in Ancient Peru". Routledge, Taylor and Francis Groupe. ISSN 0037-9816.

- Urton, Gary. 2017. Inka history in knots. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Domenici, Davide (1996). "Talking Knots of the Inka". Archaeology. 49 (6): 13–24.

- "Quipu". 2012.

- Locke, Leland (1912). "The Ancient Quipu, a Peruvian Knot Record". American Anthropologist. 14 (2): 325–332. doi:10.1525/aa.1912.14.2.02a00070.

- National Geographic (1996). "Accounting Cords".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quipu. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Quipus. |

- The Khipu Database Project at Harvard University (gallery, archives, references, researchers, etc.)

- Quipu: A Modern Mystery

- Speaking of Graphics: The Quipu and Statistical Graphics

- Untangling the Mystery of the Inca

- From Knots to Narratives

- Science: Inka Accounting Practices

- Open / Popular (Ad Hoc) Khipu Decipherment Project

- Open / Popular (Ad Hoc) Khipu Decipherment Project (now on FACEBOOK)

- History of Counting-PlainMath.Net

- High in the Andes, Keeping an Incan Mystery Alive (New York Times, August 16, 2010)

- The Khipu of San Cristobal de Rapaz

- “Making Sense of the Pre-Columbian,” Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520-1820.

Discovery of "Puruchuco" toponym

- Experts 'decipher' Inca strings – BBC

- Peruvian ‘writing’ system goes back 5,000 yearsArchived April 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. – MSNBC

- American Textile History Museum

- American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works