Khedda

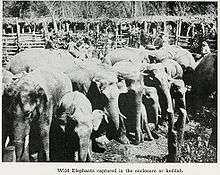

A khedda (or Kheddah) or the Khedda system was a stockade trap for the capture of a full herd of elephants that was used in India; other methods were also used to capture single elephants.[1] The elephants were driven into the stockade by skilled mahouts mounted on domesticated elephants.[2][1] This method was practiced widely in North-east India, particularly in the state of Assam,[3] mostly in South India,[4] and in particular in the erstwhile Mysore State (now part of Karnataka) state.[5]

The khedda practice and other methods of trapping or capturing elephants have been discontinued since 1973 following the enactment of a law under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, declaring the Indian elephant to be a highly endangered species. In the case of elephants which cause extensive damage by encroaching into human habitations and damaging crops, the forest department has the authority to capture them.[3]

Etymology

Khedda is a word in the Hindi language meaning a "ditch", which was used as a trap to capture many wild elephants. Prior to introduction of this system the method used to trap wild elephants was a pit system.[6]

History

An early description of a khedda was written by the Greek explorer and ambassador to India, Megasthenes (ca. 350 – 290 BC), on which Strabo based his account in Geographica.[7] The description was similar to the modern technique.[8] Female elephants were used as bait. When the captured elephants were worn out by famine and combat with tame elephants, their legs were tied. Finally their necks were lacerated, and leather straps inserted in the cuts "so that they submit to their bonds through pain, and so remain quiet."[9]

Man-elephant conflict is a major factor in either capturing them or hunting them for economic purpose. Four methods of trapping them have been practiced. These methods are: by trapping them in pits; by kheddah operations for capturing a herd of elephants, by driving into kheddas or enclosures, or driving the herd through the river-drive method; by noosing them with the help of mahouts sitting on the backs of trained elephants, mostly adopted to capture single elephants; and using decoy or lure by tamed female elephants and then spearing them.[1][3]

In Mysore

In Mysore, the khedda system was first introduced by G P. Sanderson in 1873–1874 at Kardihalli. The venue of such events was the Kakanakote forest on the banks of the Kabini River. This was organized by the forest department at frequent intervals, usually coinciding with the visit of a dignitary to the state. Tipu Sultan, the ruler of Mysore, had failed to capture elephants.[5] Tipu Sultan and his father Hyder Ali were not successful in trapping wild elephants in spite of using their army. The first attempt to capture the elephants by Colonel Pearson, a British Army Officer, had also failed. However, G.P. Sanderson, who worked for the government of Mysore in the forest department, in his book titled Thirteen Years Among The Wild Beasts of India has noted: "Hyder made a trial, a century before, in the Kakanakote Jungles, but had failed and had recorded his opinion that no one would ever succeed, and his curse upon any one that attempted to do so, on a stone still standing near the scene of his endeavors.” The term “game” is used to denote wildlife hunting as an official royal sport, which was practiced by the erstwhile Maharajas of princely states of India like Mysore in which British officers also took keen interest. Such games were specifically arranged as an entertainment to visiting Dukes and Viceroys. One such khedda operation was arranged by Sanderson by the river-drive method through the Kabini River in honour of the Grand Duke of Russia when he visited Mysore, in 1891.[10]

Following the successful operation of the first khedda by Sanderson, this system, started in Kakanakote became very popular in Mysore. Over the next century 36 khedda operations were held till 1971 when it was legally banned under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 as it was considered a crude and gruesome method perpetrated on animals.[10]

In Assam

In Assam which is reported to have the largest population of elephants in the country, the practice followed to catch elephants was by the khedda system, also known as Mela Shikar kheddas are further classified as the Pung Garh and the Dandi Garh.[3][11] In Bengal also the practice followed was khedda and this operation was performed by the Government of Bengal to capture elephants for its use.[12]

In other states

In the Madras State, now Tamil Nadu, and in Kerala, the practice followed to capture a small number of elephants was by the pit method during the monsoon months of July to September. The elephants were captured and tamed to meet the demands of temples and to move timber in the forests.[3][11] Noosing, using the trained elephants backs, is the practice adopted in Bengal and also in Nepal. In this method three or four fast moving tamed elephants, each with three mahouts as guides were used in this method with the rope tied to the tame elephants body with the other end used as a noose.[1]

Khedda system

The composition of the team for the khedda system to trap elephants comprised drum beaters, mahouts, security men, assistants and trained elephants known as kumkis. After locating a herd of wild elephants to be captured it was encircled by the team of the hunters sealing all routes of escape. A fenced circuit of 16–21 km2 (6–8 sq mi) area was created and cordoned around the herd; this was stocked with adequate supply of feeds and water and well camouflaged.[10]

To prevent elephants from going astray, big fires were lit, shouting done, drums beaten and gun shots fired to scare the elephants and keep them confined. Following this activity of keeping the elephants within the confined space, building of the enclosure was carried out. This enclosure, located in a camouflaged area along one of the main paths of the elephant, was built to dimensions of about 20–50 m (20–50 yd) diameter raised to a height of 4 m (12 ft). The enclosure was fortified with slanting buttresses and ties. A highly secure entrance gate fitted with spikes was built. The entrance path to guide the elephants was done through two palisades. The herd of wild elephants, scared by din and sound and fire, were forced to go through the "funnel-shaped" route into the enclosure and then the gates were shut.[10] Following the capture in the trap, elephants were denied food, forced to starve and were even injured, which made them weak.[4] Thus confined into the khedda the wild elephants were then approached by the mahouts with the trained elephants to pacify them.[10]

Then the mahout with the assistance of a helper prodded the wild elephant with an iron rod to lift its one leg so that it could be noosed with ropes. Using the same procedure, the other three legs and the neck of the elephant were noosed, and wild elephants subject to the discomfort and being immobilized would become easier to control.[10] Once tamed they were trained.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Sanderson 1879, p. 70.

- ↑ Diver, Katherine H.; Maud Diver (1942). Royal India. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 0-8369-2152-6. OCLC 141359.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Elephant Protocols, Manuals, and Proceedings". History of elephant capture: Section VI. Elephant Welfare Association. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 Kamat, Vikas. "The Khedda System of Catching Wild Elephants". Kamat's Potpourri. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- 1 2 Stracey 1964, p. 61.

- ↑ Ninan 2012, p. 112.

- ↑ A. B. Bosworth (1988). From Arrian to Alexander: Studies in Historical Interpretation. Clarendon Press. pp. 43–. ISBN 978-0-19-814863-0.

- ↑ E. J. Rapson (1922). The Cambridge history of India, p.405 https://archive.org/stream/cambridgehistory01rapsuoft/cambridgehistory01rapsuoft_djvu.txt. Retrieved 30 January 2016. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Strabo (7 April 2014). The Geography of Strabo : Volume III (Illustrated). Lulu.com. pp. 109–. ISBN 978-1-312-07866-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Satish, Shalini (10 May 2010). "Deep in the jungles of Kakanakote...". Deccaan Herald. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- 1 2 Stracey 1964, p. 60.

- ↑ Sanderson 1879, p. 92.

Bibliography

- Ninan, K.N (16 May 2012). The Economics of Biodiversity Conservation: Valuation in Tropical Forest Ecosystems. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-55426-1.

- Sanderson, G. P. (1879). "Thieteen Years Among The Wild Beasts Of India. Their Haunts And Habits From Personal Observation; With An Account Of The Modes Of Capturing And Taming Elephants.". Archive Organization. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- Stracey, P. D. (1964). Wild Life in India: Its Conservation and Control. Department of Agriculture.