Dwarf (Middle-earth)

| Khazâd, Hadhodrim, Naugrim | |

|

An illustration of a Middle-earth dwarf, by a fan artist. | |

| Attributes | |

|---|---|

| Founder |

Aulë Durin and the other Fathers of the Dwarves |

| Leader(s) | Kings of Durin's folk had precedence over all Dwarf-lords |

| Home world | Middle-earth |

| Base of operations | Khazad-dûm (to T.A. 1981), Blue Mountains, Lonely Mountain, Iron Hills |

| Language | Khuzdul |

| Races | Longbeards, Broadbeams, Firebeards, Ironfists, Stiffbeards, Blacklocks, Stonefoots (see #Divisions below) |

| Races of Middle-earth |

|---|

| Ainur |

| Other races |

In the fantasy of J. R. R. Tolkien, the Dwarves are a race inhabiting Middle-earth, the central continent of Earth in an imagined mythological past. They are based on the dwarfs of Germanic myths: small humanoids that dwell in mountains, and are associated with mining, metal-craft and jewelry.

They appear in his books The Hobbit (1937), The Lord of the Rings (1954–55), the posthumously published The Silmarillion (1977), Unfinished Tales (1980), and The History of Middle-earth series (1983–96), the last three edited by his son and literary executor Christopher Tolkien.

Development

The Book of Lost Tales

In The Book of Lost Tales the very few Dwarves who appear are portrayed as evil beings, employers of Orc mercenaries and in conflict with the Elves—who are the imagined "authors" of the myths, and are therefore biased against Dwarves.[1][2] Tolkien was inspired by the dwarves of Norse myths[3][4] and dwarves of Germanic folklore (such as those of the Brothers Grimm), from whom his Dwarves take their characteristic affinity with mining, metalworking, crafting and avarice.[4]

The Hobbit

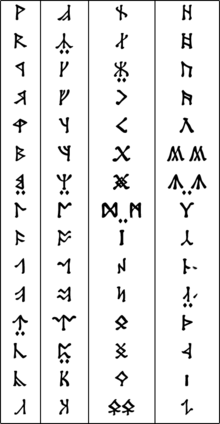

The representation of Dwarves as evil changed dramatically with The Hobbit. Here the Dwarves became occasionally comedic and bumbling, but largely seen as honourable, serious-minded, but still portraying some negative characteristics such as being gold-hungry, extremely proud and occasionally officious. Tolkien was now influenced by his own selective reading of medieval texts regarding the Jewish people and their history.[5] The dwarves' characteristics of being dispossessed of their homeland (the Lonely Mountain, their ancestral home, is the goal the exiled Dwarves seek to reclaim), and living among other groups whilst retaining their own culture are all derived from the medieval image of Jews,[5][6] whilst their warlike nature stems from accounts in the Hebrew Bible.[5] Medieval views of Jews also saw them as having a propensity for making well-crafted and beautiful things,[5] a trait shared with Norse dwarves.[4] For The Hobbit almost all dwarf-names are taken from the Dvergatal or "Catalogue of the Dwarves", found in the Poetic Edda.[7][8] However, more than just supplying names, the "Catalogue of the Dwarves" appears to have inspired Tolkien to supply meaning and context to the list of names—that they travelled together, and this in turn became the quest told of in The Hobbit.[9] The Dwarves' written language is represented on maps and in illustrations by Anglo-Saxon Runes. The Dwarf calendar invented for The Hobbit reflects the Jewish calendar in beginning in late autumn.[5] The dwarves taking Bilbo out of his complacent existence has been seen as an eloquent metaphor for the "impoverishment of Western society without Jews."[6]

The Lord of the Rings

by Perrie Nicholas Smith.

When writing The Lord of the Rings Tolkien continued many of the themes he had set up in The Hobbit. When giving Dwarves their own language (Khuzdul) Tolkien decided to create an analogue of a Semitic language influenced by Hebrew phonology. Like medieval Jewish groups, the Dwarves use their own language only amongst themselves, and adopted the languages of those they live amongst for the most part, for example taking public names from the cultures they lived within, whilst keeping their "true-names" and true language a secret.[10] Along with a few words in Khuzdul, Tolkien also developed runes of his own invention (the Cirth), said to have been invented by Elves and later adopted by the Dwarves. Tolkien further underlines the diaspora of the Dwarves with the lost stronghold of the Mines of Moria. In The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien uses the main dwarf character Gimli to finally reconcile the conflict between Elves and Dwarves through showing great courtesy to Galadriel and forming a deep friendship with Legolas, which has been seen as Tolkien's reply toward "Gentile anti-Semitism and Jewish exclusiveness".[6]

Tolkien also elaborated on Jewish influence on his Dwarves in a letter: "I do think of the 'Dwarves' like Jews: at once native and alien in their habitations, speaking the languages of the country, but with an accent due to their own private tongue..."[11]

The "Quenta Silmarillion"

After preparing The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien returned again to the matter of the Silmarillion, in which he gave the Dwarves a creation myth. The most Dwarf-centric story from The Book of Lost Tales, "The Nauglafring", was not redrafted to fit with the later positive portrayal of the dwarves from The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, nor other events in the Silmarillion,[12] leading Christopher Tolkien significantly to rewrite it with input from Guy Gavriel Kay in preparation for publication.

The Later Silmarillion and last writings

Sometime before 1969 Tolkien wrote the essay Of Dwarves and Men, in which detailed consideration was given to the Dwarves' use of language, that the names given in the stories were of Northern Mannish origin, and Khuzdul being their own secret tongue and the naming of the Seven Houses of the Dwarves. The essay represents the last of Tolkien's writing regarding the Dwarves and was published in volume 12 of The History of Middle-earth in 1996.

In the last interview before his death, Tolkien, after discussing the nature of Elves, briefly says of his Dwarves: "The dwarves of course are quite obviously, wouldn't you say that in many ways they remind you of the Jews? Their words are Semitic, obviously, constructed to be Semitic."[13]

Spelling "Dwarves"

The original editor of The Hobbit "corrected" Tolkien's plural dwarves to dwarfs, as did the editor of the Puffin paperback edition of The Hobbit.[14] According to Tolkien, the "real 'historical'" plural of dwarf is dwarrows or dwerrows.[15] He referred to dwarves as "a piece of private bad grammar".[16] In Appendix F of The Lord of the Rings it is explained that if we still spoke of dwarves regularly, English might have retained a special plural for the word dwarf as with goose—geese. Despite Tolkien's fondness for it, the form dwarrow only appears in his writing as Dwarrowdelf, a name for Moria.

Tolkien used Dwarves, instead, which corresponds with Elf and Elves. In this matter, one has to consider the fact that the etymological development of the term dwarf differs from the similar-sounding word scarf (plural scarves). The English word is related to old Norse dvergr, which, in the other case, would have had the form dvorgr. But this word was never recorded, and the f/g-emendation (English/Norse) dates further back in language history.

Adjectives

Tolkien used dwarvish[17] and dwarf(-) (e.g. Dwarf-lords, Old Dwarf Road) as adjectives for the people he created, rarely dwarven if ever.

Wicked Dwarves

Of the people of Middle-earth, Dwarves are the most resistant to corruption and influence of Morgoth and later Sauron. The seven rings of Power of the dwarves did not turn them to evil, but it did amplify their greed and lust for gold. It is said that very few wilfully served the side of darkness. Of those who did very little was written.[18] Of the seven houses few fought on either side during The Last Alliance at the end of the Second Age, and it's known that none from the House of Durin ever fought on the side of evil.[19] During the early parts of the Third Age (or at least in legends of the previous), it is known that in some places wicked dwarves had made alliances with orcs.[20] It is suggested by Tolkien in some of his notes that of the dwarves that turned to wickedness they most likely came from the Dwarves of the far eastern mansions (and perhaps some of the nearer ones) came under the Shadow of Morgoth and turned to evil. It is however unclear if these refer to Dwarves beyond Iron Hills (the most eastern known stronghold of the Dwarves).[21] Because Dwarves are not evil by nature, few ever served the Enemy of their own free will (though rumours of Men suggest the total was greater).[22]

Some of the dwarves accused of fighting on the side of darkness may have been in conflict due to enmity between the races due to misunderstandings (which may also apply to the Petty-dwarves' distrust and hatred of the elves), or enmity between the races caused by greed and envy (men lusting after the dwarves' wealth and their handiwork, and possibly between the Dwarvish clans themselves), or by races becoming estranged from each other (the rise of the enmity and distrust between dwarves and elves after the fall of Khazad-dûm). What may have been fought in self-defence may be seen as an evil action by the opposing force. But in these cases those involved were never allied with the Enemy or his ambassadors (though the wars between the Free Peoples may have worked to his advantage). The trust and interaction between elves and dwarves was later restored through the friendship of Legolas and Gimli.

Literature

Characteristics

In The Silmarillion, the Dwarves are described as shorter and stockier than Elves and Men, able to withstand both heat and cold. Though they are mortal, Dwarves have an average lifespan of 250 years.[23]

In The Lord of the Rings Tolkien writes that they breed slowly, for no more than a third of them are female, and not all marry; also, female Dwarves look and sound (and dress, if journeying—which is rare) so alike to Dwarf-males that other folk cannot distinguish them, and thus others wrongly believe Dwarves grow out of stone. Tolkien names only one female, Dís.

Tolkien's Dwarves, much like their mythical forebears, are great metalworkers, smiths and stoneworkers. Fierce in battle, their main weapons are axes (referenced in many subsequent fantasy works), but they also use bows, swords, shields and mattocks.[24] Unlike other fantasy dwarves, Tolkien does not explicitly have them use war hammers.

Since they lived underground, Dwarves did not grow their own food supplies if they could help it, and usually obtained food through trade with Elves and Men. In the essay "Of Dwarves and Men" in The Peoples of Middle-earth it is written that Dwarf and human communities often formed trade relations where the Men were the prime suppliers of food, farmers and herdsmen, while the Dwarves supplied tools and weapons, road-building and construction work.

Unlike Elves and Men, created by the supreme god Ilúvatar, Dwarves were created by the Vala Aulë.

Throughout the First Age and most of the Second Age, the Dwarves maintain mostly friendly trading relations with Men and Elves (the treachery of the Dwarves of Nogrod towards Thingol of Doriath being an exception). However, in the Third Age, particularly after the closure of Moria, they grow mistrustful of Elves, though in later times cordial relations are established with the Elves of Mirkwood and the Men of Dale. They also maintain somewhat ambivalent relations with Hobbits for most of the Third Age, although after the mission to retake the Lonely Mountain Bilbo Baggins is held in great esteem there.

Language

From their creation, the Dwarves spoke Khuzdul, a constructed language made for them by Aulë. Because it was a constructed (though living) language, it was not descended from any form of Elvish, as most of the languages of Men were, although it is suggested that the language may have had influence on the early languages of Men.[25] Khuzdul was for the most part a closely guarded tongue (one of the few recorded outsiders to have a knowledge of it was Eöl), however, and the Dwarves never revealed their Khuzdul names to outsiders, going so far as to omit them from even their tombs. Khuzdul was written in Cirth, a runic alphabet developed by the Elves. There is no extant corpus for the Khuzdul language, whether in Tolkien's novels or in his private works, other than the battle cry: Baruk Khazâd! Khazâd ai-mênu! (meaning "Axes of the Dwarves! The Dwarves are upon you!") and the inscription on Balin's tombstone, reading: BALIN FUNDINUL UZBAD KHAZAD-DÛMU, or Balin son of Fundin Lord of Moria. The remainder of the corpus of Khuzdul consists of single words and names, such as the mountains Barazinbar (Redhorn) and Zirakzigil (Silvertine). Tolkien himself does not seem to have had a firm idea of the meaning of these words when he created them; his notes on Zirakzigil originally suggested that "zirak" means "silver" and "zigil" means "spike", but he later reversed this and proposed that "zirak" is "spike" and "zigil" is "silver". Of another Khuzdul name "Kibil-nâla" he wrote "the meaning of nâla is not known."[26]

Names

In the Grey-elvish or Sindarin the Dwarves were called Naugrim ("Stunted People"), Gonnhirrim ("Stone-lords"), and Dornhoth ("Thrawn Folk"), and also Hadhodrim. In Quenya they were the Casári. The Dwarves called themselves Khazâd in their own language, Khuzdul.

Tolkien took the names of twelve of the thirteen dwarves he used in The Hobbit (and Gandalf's name as well) from Völuspá.

Divisions

In The Silmarillion, it is stated that the Dwarves were originally divided into seven clans or "Houses". The three who enter Tolkien's histories are:

- Longbeards (Khuzdul: Sigin-tarâg) (Durin's folk), who founded the city of Khazad-dûm in the Misty Mountains (they later founded realms in the Grey Mountains and the Lonely Mountain);

- Firebeards, who founded Nogrod in the Blue Mountains;

- Broadbeams, who founded Belegost in the Blue Mountains.

After the end of the First Age, the Dwarves spoken of are almost exclusively of Durin's line. Almost nothing is known of the histories of the other four Houses, except that they each sent a contingent west to fight in The War of the Dwarves and Orcs in the late Third Age, and their names:

- Ironfists

- Stiffbeards

- Blacklocks

- Stonefoots

Petty-dwarves

The Petty-dwarves were Dwarves of several houses, which had been exiled in very ancient times for reasons unknown. They were the first to cross the Ered Luin in the First Age, and established strongholds in Beleriand before the building of Nogrod and Belegost in the Blue Mountains, and before the Elves arrived. These very ancient settlements were at Nargothrond and Amon Rûdh.

The usual Sindarin name was Noegyth Nibin; others include Nibin-Nogrim and Noegoethig, formed of nibin ("petty") and one of the Elvish names for the true Dwarves. In Quenya they were called Pitya-naukor. The Petty-dwarves of West Beleriand dwindled to a single family, and then at last became extinct.

The Sindar, not acquainted with Dwarves yet, saw the Petty-dwarves as little more than bothersome animals, calling them (Levain) Tad-dail ("two-legged (animals)"), and hunted them.[27][28] Not until the Dwarves of the Ered Luin established contact with the Sindar did they realize what the Petty-dwarves were. Afterwards they were mostly left alone, but not before the Petty-dwarves came to hate all Elves with a passion.

Petty-dwarves differed from normal Dwarves in various ways: they were smaller, far more unsociable, and they freely gave away their names: other Dwarves kept their Khuzdul names and language a secret. In reality, Tolkien's original conception was that all Dwarves were greedy, treacherous and unable to create works of beauty without aid. This was so different from their characteristics that evolved in later stories that he felt obliged to describe the Dwarves in these earlier stories as a separate race, the Petty-dwarves.[29]

By the time of the War of the Jewels, after the return of the Noldor, the Petty-dwarves had nearly died out. The last remnant of their people were Mîm and his two sons, Ibun and Khîm, who lived at Amon Rûdh. They gave shelter to Túrin Turambar and his band at their home of Amon Rûdh. Mîm was later captured by a band of Orcs and saved his own life by betraying Túrin, though his sons were killed. Mîm later became the possessor of a treasure-hoard abandoned by the dragon Glaurung, but was later killed by Húrin, Túrin's father.

History

The Dwarves are portrayed as a very ancient people who awoke, like the Elves, at the start of the First Age, before the existence of the Sun and Moon (the Elves, however, awakened first).

Creation

In Tolkien's works, the Dwarves (in the form of seven patriarchs) were created during the Years of the Trees (also known as the Ages of Darkness), when all of Middle-earth was controlled by the forces of Melkor. They were created by the Vala Aulë, in secret from the other Valar, intended to be his children to whom he could teach his crafts. Ilúvatar, however, knew of their creation, despite Aulë's efforts. When confronted by Ilúvatar, Aulë confessed his deed and raised his hammer to destroy his creations. However, Ilúvatar, seeing that they had been made not out of malice or wickedness, stayed Aulë's hand and sanctified the dwarves, though he did not allow them to "awake" before the Elves (whom he had designated as "The Firstborn"). Aulë sealed the seven Fathers of the Dwarves in stone chambers in far-flung regions of Middle-earth to await their awakening.

First Age

Some time after the Elves had awakened at Cuiviénen, the Seven Fathers of the Dwarves were released from their stone chambers. The eldest of them, called Durin, wandered until he founded the city of Khazad-dûm in the natural caves beneath three peaks: Caradhras, Celebdil, and Fanuidhol (known in Khuzdul as Baranzinbar, Zirakzigil, and Bundushathûr, respectively). The city, populated by the Longbeards or Durin's folk, grew and prospered continuously through Durin's life (which was so long that he was called Durin the Deathless, also a reference to the belief by his people that he would be reincarnated seven times). It was the only one of the Dwarf mansions to survive the First Age.

Far to the west of Khazad-dûm, the great dwarvish cities of Belegost and Nogrod were founded in Ered Luin (The Blue Mountains) during the First Age, before the arrival of the Elves in Beleriand. The Dwarves of Belegost were the first to forge mail of linked rings, and they also traded weaponry with the Sindar and carved the Thousand Caves of Menegroth for the Elf king Thingol. In Nogrod, the smith Telchar forged Narsil and Angrist, two of the most fateful weapons in the history of Arda, as well as the famed Dragon-helm of Dor-Lómin.

The dwarves of Beleriand fought against the forces of Melkor during the first age, and the dwarves of Belegost were the only people able to withstand dragon-fire in the Battle of Unnumbered Tears, when King Azaghâl, who died in the battle, stabbed Glaurung, the first dragon.

The dwarves of Nogrod fought against Melkor as well. However, they slew Thingol out of greed and stole the Silmaril they had been charged to set into the necklace called Nauglamír. A number of retaliatory actions ensued, and the Nogrod army was destroyed by a force of Laiquendi and Ents. Both dwarf kingdoms would eventually be destroyed, along with nearly all of Beleriand, after the War of Wrath, with the dwarvish refugees mainly resettling in Khazad-dûm.

Second Age

Refugees from Belegost and Nogrod added to the population of Khazad-dûm, and its wealth was also enriched with the discovery of mithril, a magical and extremely valuable metal found only in its mines. During this time the Dwarves continued to trade with neighbouring Men and the Elves of Eregion. Seven of the Rings of Power forged by the Elven-Smiths were later given by Sauron, who had seized them, to the heads of the seven Dwarf clans (although the Longbeards maintained that Durin's Ring was given to him by Celebrimbor). The Dwarves of Moria at first fought in the War of Sauron and the Elves, but in the year 1697 of the Second Age, the doors of Khazad-dûm were shut and its inhabitants no longer ventured forth into the world. Thereafter it was known by the elven name of Moria, meaning "dark chasm".

Third Age

During the Third Age the Dwarves of Moria continued to prosper until the year 1980, when, in pursuing a vein of mithril, they broke open a chamber containing the last balrog known in the histories of Middle-earth, called Durin's Bane. They battled against the demon for one year, and after the death of two kings, the Dwarves who had not been killed fled from the Misty Mountains. For almost two decades they had no kingdom, but in the year 1999, Thráin I founded a kingdom at the Lonely Mountain. This kingdom prospered for a time, and the great jewel known as the Arkenstone was discovered.

In 2210 Thorin I founded a kingdom in the Grey Mountains to the north of Mirkwood. Both of these realms would eventually be consumed by dragons—the Grey Mountains in 2590 by a horde and The Lonely Mountain in 2770 by the dragon Smaug. The refugees from the Grey Mountains who did not return to The Lonely Mountain colonized the Iron Hills, one of the only Dwarf kingdoms never to be abandoned or taken. The main body of the Dwarves became a wandering people, and Thrór, who had been king of the Lonely Mountain when it was captured, was slain by Orcs in the year 2790 and his body mutilated. This led to the War of the Dwarves and Orcs, in which nearly all of the Orc hordes of the Misty Mountains were exterminated but half of the Dwarf host were killed, a blow that took the Dwarves several hundred years to recover from.

For a time an exile kingdom was founded in the northern Blue Mountains, but Thráin II was driven to wandering the wilderness by his Ring, the last of the Dwarvish Rings not yet taken by Sauron or consumed by dragons. He was soon captured by Sauron, then reigning as the Necromancer in Dol Guldur. Thráin was tortured, his Ring of Power taken, and finally died. In 2941 Thorin II Oakenshield, son of Thráin II and grandson of Thrór, recolonized the Lonely Mountain after Smaug the dragon was slain by Bard, the future King of Dale. After the ensuing Battle of the Five Armies, in which the Eagles, the Elves of Mirkwood, the Men of Dale, and the Dwarves of the Iron Hills (as well as Thorin's band) defeated an invading horde of Goblins and in which Thorin was killed, his cousin Dáin II Ironfoot, already lord of the Iron Hills, became King Under the Mountain, and the Lonely Mountain was not abandoned again.

Dwarves did not figure prominently in the major battles of the War of the Ring although the Lonely Mountain was besieged for a time and Dáin killed in the Battle of Dale. One dwarf, however—Gimli—joined the Fellowship of the Ring and was a companion of the Ringbearer for a great part of his journey, and also fought at the Battle of the Hornburg, the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, and the Battle of the Morannon.

Fourth Age

At the start of the Fourth Age, Gimli led a group of colonists from the Lonely Mountain to the Glittering Caves, beneath Hornburg in Rohan, where he established another Dwarf kingdom and ruled there for more than a century. After the death of Aragorn in the year 120 of the Fourth Age, he sailed to the Undying Lands with Legolas.

It is said that the Dwarf population began to dwindle because most male Dwarves did not desire wives, or could not find one that they desired. It does not help that Dwarf women are less than a third of the population (and many of them choose not to marry, as well).[30] Yet much is still left a mystery in Dwarvish history; the Dwarves' true fate is left unknown.

Adaptations

.jpg)

In Iron Crown Enterprises' Middle-earth Role Playing (1986) Dwarven player-characters receive statistical bonuses to Strength and Constitution, and subtractions from Presence, Agility and Intelligence. Seven "Dwarven Kindreds", named after each of the founding fathers – Durin, Bávor, Dwálin, Thrár, Druin, Thelór and Bárin – are given in The Lords of Middle-earth—Volume III (1989).

In Peter Jackson's live action adaptation of The Lord of the Rings film trilogy, Gimli's character is occasionally used as comic relief and several of his appearances are intended to emphasize the difference between the Dwarves and Elves.

As explained in the DVD commentary, the races in the Fellowship come in three height ranges: regular sized Men and Elves, Dwarves who average four feet six inches (1.37 m), and Hobbits who average three feet six inches (1.06 m). The adaptation had to digitally composite certain wide shots in which all of them appear, as well as make use of stunt doubles and various camera perspective tricks. However, while the different races come in three size ranges, the adaptations only used two different size scales, by putting both Dwarves and Hobbits into the same size scale. This was achieved by simply casting tall actors to play Dwarves, who thus seem proportionately taller than the average-height Hobbit actors, without the need for camera tricks or digital compositing. Thus Gimli rarely interacts with Men and Elves within the same camera frame, or when he does, Gimli is actually played by a shorter stunt double seen from behind. In contrast, because Dwarves and Hobbits are in the same size scale, Gimli interacts freely with the Hobbit characters within the same camera frame. A good example is when the Fellowship enters Lothlórien, and Gimli walks up to Frodo and puts his hand on his shoulder, warning him to stay close. Actor John Rhys-Davies is actually 6'1'' (1.85 m) (two inches (5 cm) taller than Viggo Mortensen, who plays Aragorn), much taller than Elijah Wood (Frodo) who is 5'6'' (1.67 m), thus keeping the proportion that Dwarves are taller than Hobbits.

Other dwarves appear in passing in two scenes of The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring movie: the "prologue" introduces the seven dwarf-lords that received the Rings of Power, and four more are present at the Council of Elrond (in contrast to the book, where only Gimli and his father Glóin are described). Peter Jackson's Dwarves wear scale armour.

In Peter Jackson's adaption of The Hobbit, a wider range of dwarves is seen: the 13 in Thorin's Company and others seen early on in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. Much more of the Dwarves' history and culture is seen throughout the main story, as with the 13 Dwarves of Thorin's Company. Examples of Khuzdul are seen, such as on Thorin Oakenshield's map, as well as the Dwarves' history, with the main story and the flashbacks. Female dwarves are actually shown on-screen briefly in the Hobbit trilogy, in the flashbacks to the fall of Erebor and Dale to Smaug the Dragon - as mentioned in the novels and first trilogy, they are depicted with beards (somewhat thinner than male beards, like very long and braided sideburns). The behind the scenes extras explain that the producers wanted to use the 13 members of Thorin's company to depict a diverse social strata, to round out their personalities and make them less monolithic. The general rule they applied was that Dwarves more closely related to Thorin and the royal line would dress in better clothing and act more aristocratic, spiraling outward: Thorin and his nephews Fili and Kili are of the royal line so they have the richest costumes, followed by Balin and Dwalin (younger cousins of the royal line but still important lords and generals); then Oin and Gloin (more distant cousins but of the royal blood, thus a respected doctor and military general, respectively); then Dori, Nori, and Ori (very distant cousins whose relation to the royal line is so distant it isn't even elaborated - they are depicted as well-to-do middle class merchants, but clearly lower on the social scale than Gloin or Dwalin); then finally, Bifur, Bofur, and Bombur (who aren't related to the royal line at all, and are depicted as humble and simply dressed working-class Dwarves, miners and toy-makers).

In Decipher Inc.'s The Lord of the Rings Roleplaying Game (2001), based on the Jackson films, Dwarf player-characters get bonuses to Vitality and Strength attributes and must be given craft skills. In the Dwarves of Middle-earth (2003) supplement, the seven Dwarf Lords and their houses are named as Durin, Sindri, Linnar, Var, Uri, Thulin and Vigdis.

In the real-time strategy game The Lord of the Rings: The Battle for Middle-earth II, and its expansion, both based on the Jackson films, Dwarves are heavily influenced by classical military practice, and use throwing axes, war hammers, spears, and circular or Roman-style shields. One dwarf unit is the "Phalanx" and is very similar to its Greek counterpart.

See also

References

- ↑ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984), Christopher Tolkien, ed., The Book of Lost Tales, 1, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, "Gilfanon's Tale", ISBN 0-395-35439-0

- ↑ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984), Christopher Tolkien, ed., The Book of Lost Tales, 2, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, "The Nauglafring", ISBN 0-395-36614-3

- ↑ Shippey, Thomas. J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins, 2000

- 1 2 3 Jane Chance, Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: A Reader (2004). University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2301-1

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rateliff, John. The History of the Hobbit. p.79-80

- 1 2 3 Owen Dudley Edwards, British Children's Fiction in the Second World War(2008) Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 0-7486-1651-9

- ↑ "10. There was Mótsognir the mightiest made / Of all the dwarfs, and Durin next; / Many a likeness of men they made, / The dwarfs in the earth, as Durin said. /11. Nyi and Nithi, Northri and Suthri, / Austri and Vestri, Althjof, Dvalin, / Nar and Nain, Niping, Dain, / Bifur, Bofur, Bombur, Nori, / An and Onar, Ai, Mjothvitnir, / 12. Vigg and Gandalf, Vindalf, Thrain, / Thekk and Thorin, Thror, Vit and Lit, / Nyr and Nyrath, / Regin and Rathvith—now have I told the list aright. / 13. Fili, Kili, Fundin, Náli, / Heptifili, Hannar, Sviur, / Frar, Hornbori, Fræg and Lóni, / Aurvang, Jari, Eikinskjaldi. / 14. The race of the dwarfs in Dvalin's throng / Down to Lofar the list must I tell; / The rocks they left, and through the wet lands / They sought a home in the fields of sand. / 15. There were Draupnir and Dolgthrasir, / Hor, Haugspori, Hlevang, Gloin, / Dori, Ori, Duf, Andvari, /Skirfir, Virfir, Skafith, Ai. / 16. Alf and Yngvi, Eikinskjaldi; / Fjalar and Frosti, Fith and Ginnar; / So for all time shall the tale be known, / The list of all the forebears of Lofar. (Poetic Edda, translated by Henry Adams Bellows. Public domain)

- ↑ "Tolkien's Middle-earth: Lesson Plans, Unit Two". Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ↑ Shippey, Thomas. J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins, 2000, pp.17

- ↑ Douglas Anderson, History of the Hobbit, Harper Collins 2006 p. 80

- ↑ Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 176, ISBN 0-395-31555-7

- ↑ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984), Christopher Tolkien, ed., The Book of Lost Tales, 2, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, "The Nauglafring, Notes", ISBN 0-395-36614-3

- ↑ Gerrolt, Dennis Now Read On... interviewBBC,1971

- ↑ The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, 138

- ↑ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=dwarf

- ↑ (Letters, 17)

- ↑ J. R. R. Tolkien (1937), The Hobbit, 4th edition (1978), George Allen & Unwin, preface; ISBN 0-04-823147-9

- ↑ http://middle-earth.xenite.org/2011/11/15/did-dwarves-ever-serve-sauron/

- ↑ Of the Dwarves few fought upon either side; but the kindred of Durin of Moria fought against Sauron. Tolkien, J. R. R. (2009-05-05). The Silmarillion (p. 352). Harper Collins, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ They did not hate dwarves especially, no more than they hated everybody and everything, and particularly the orderly and prosperous; in some parts wicked dwarves had even made alliances with them. Tolkien, J.R.R. (2009-04-17). The Hobbit (Kindle Locations 1057-1059). Harper Collins, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ 28. For they had met some far to the East who were of evil mind. [This was a later pencilled note. On the previous page of the typescript my father wrote at the same time, without indication of its reference to the text but perhaps arising from the mention (p. 301) of the awakening of the eastern kindreds of the Dwarves: 'Alas, it seems probable that (as Men did later) the Dwarves of the far eastern mansions (and some of the nearer ones?) came under the Shadow of Morgoth and turned to evil.'] Peoples of Middle-earth, HoME 12

- ↑ But they [Dwarves] are not evil by nature, and few ever served the Enemy of free will, whatever the tales of Men may have alleged. For Men of old lusted after their wealth and the work of their hands, and there has been enmity between the races. (Appendix F to LoTR)

- ↑ A Guide to Tolkien, David Day, Chancellor Press, 2002

- ↑ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937), Douglas A. Anderson, ed., The Annotated Hobbit, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 2002), "The Gathering of the Clouds", ISBN 0-618-13470-0

- ↑ The Languages of Tolkien's Middle-earth, Ruth S. Noel, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1980

- ↑ Christopher Tolkien (1989), The History of Middle-Earth, The Treason of Isengard, p.174; ISBN 0-395-51562-9

- ↑ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980), Christopher Tolkien, ed., Unfinished Tales, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, "Of Túrin Turambar", ISBN 0-395-29917-9

- ↑ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980), Christopher Tolkien, ed., Unfinished Tales, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, "Narn i Hîn Húrin", ISBN 0-395-29917-9

- ↑ John D. Rateliff (2007), The History of The Hobbit, Part One Mr. Baggins, p.78; ISBN 0-618-96847-4

- ↑ Return of the King, Appendix

External links

- "Dwarves". Tolkien Gateway.

- Khuzdul - the secret tongue of the Dwarves at Ardalambion

- Dwarves - More on Tolkien's Dwarves at The Dwarrow Scholar