Uesugi Kenshin

| Uesugi Kenshin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | 上杉 謙信 |

| Birth name | Nagao Kagetora |

| Nickname(s) | Dragon of Echigo, God of War, Tiger of Echigo, Guardian of the North |

| Born |

February 18, 1530 Echigo Province, Japan |

| Died |

April 19, 1578 Echigo Province, Japan |

| Allegiance | Nagao clan, Uesugi clan |

| Rank | Lord (Daimyō) |

| Battles/wars |

|

Uesugi Kenshin (上杉 謙信, February 18, 1530 – April 19, 1578) was a daimyō who was born as Nagao Kagetora,[1] and after the adoption into the Uesugi clan, ruled Echigo Province in the Sengoku period of Japan.[2] He was one of the most powerful daimyōs of the Sengoku period. While chiefly remembered for his prowess on the battlefield, Kenshin is also regarded as an extremely skillful administrator who fostered the growth of local industries and trade; his rule saw a marked rise in the standard of living of Echigo.

Kenshin is famed for his honourable conduct, his military expertise, a long-standing rivalry with Takeda Shingen, his numerous campaigns to restore order in the Kantō region as the Kanto Kanrei, and his belief in the Buddhist god of war — Bishamonten. In fact, many of his followers and others believed him to be the Avatar of Bishamonten, and called Kenshin "God of War".

Name

His original name was Nagao Kagetora (長尾景虎).[3] He changed his name to Uesugi Masatora (上杉政虎) when he inherited the Uesugi clan name in order to accept the official title of Kantō Kanrei (関東管領). Later he changed his name again to Uesugi Terutora (上杉輝虎) to honor the 13th shogun Ashikaga Yoshiteru (足利義輝), and finally to Kenshin (上杉謙信) after he vowed to become a Zen-Buddhist; in particular, he would become renowned for being a devotee of Bishamonten.[4][5][6]

Kenshin is sometimes referred to as "The Dragon of Echigo" because of his fearsome skills in the martial arts displayed on the battlefield. His rival Takeda Shingen was called "The Tiger of Kai". In some versions of Chinese mythology (Shingen and Kenshin had always been interested in Chinese culture, especially the works of Sun Tzu), the Dragon and Tiger have always been bitter rivals who try to defeat one another, but neither is ever able to gain the upper hand. They fought several times at Kawanakajima.[7]

His ceremony of departure to war started with praying at the shrine of Bishamonten, a traditional farewell meal with the generals with three dishes (symbolizing good fortune) and three cups, which also symbolized good luck and onmyōdō's heaven, earth and man. It was followed by two shouts "Ei!" (Glory") and "O!" (Yes!) with the assembled troops, also repeated three times, and the army standard lowered to the generals as a way of respect. In the end, Kenshin re-dedicate to the war god with the "bow of Hachiman", and mounted his horse surrounded by three flag banners; first with the first character of the Bishamonten's name, second with the red rising sun on blue (Emperor's gift), and the warring dragon flag.[8]

Early life

.jpg)

Born as Kagetora, he was the third or fourth son of the noted warrior Nagao Tamekage (長尾為景),[1] and his life presents a unique story - he was not from the Uesugi, but Nagao clan.[3] His father's family were the retainers of the Yamanouchi branch of the Uesugi clan,[9] and his father has gained some renown with his military victories over his lords Uesugi Akisada, Sadanori and Funayoshi. However, in later years, Tamekage found himself at odds with the neighboring Ikkō-ikki of Hokuriku, and as the political power in the region started to shift in favor of the Ikkō (due largely to the sudden rise of Hongan-ji), the situation for Echigo quickly deteriorated. It came to a peak in 1536, when Kenshin's father gathered up an army and marched westward. However, upon arriving at Sendanno (December 1536) in Etchū, his forces were suddenly attacked by Enami Kazuyori, and in the resulting battle Tamekage himself was slain, and his army put to flight.[10]

The impact back at Echigo was immediate. Nagao Harukage, Tamekage's eldest son, immediately made his bid for control of the Nagao, and succeeded in this claim after a power struggle which resulted in the death of one of his brothers, Kageyasu. Kenshin was removed from the conflict and relocated to Rizen temple, where he spent his life from 7 to 14 dedicated to study.

Early Rise

At the age of 14, Kenshin was suddenly contacted by Usami Sadamitsu and a number of other acquaintances of his late father. They urged the young Nagao son to go to Echigo and contest his older brother's rule. It would seem that Harukage hadn't proven the most effective or inspiring leader (probably due to ill health[11]), and his failure to exert control and gain support of the powerful kokujin families had resulted in a situation which was nearly to the point of tearing the province apart. As the story is told, at first Kenshin was reluctant to take the field against his own brother, but was eventually convinced that it was necessary to the survival of Echigo. At the age of 15 he was placed in joint command of Tochio castle, making a reputation for himself by successfully defending it against the rebels who were plotting against the Uesugi,[3] and Kenshin succeeded in wresting control of the clan from Harukage in 1548. He stepped down from the lead of the clan and provincial government, and gave the titles to his younger brother. Harukage died five years later in 1553.[12] At the age of 19 he became the head of the family and entered the Kasugayama Castle, but still as the retainer of the Uesugi clan.[3]

In the year 1551, Kenshin was called upon to provide refuge in his castle for his nominal lord, Uesugi Norimasa, who had been forced to flee there due to the expansion into the Kantō region by the lord Hōjō Ujiyasu from the Hōjō clan. He agreed to give the warlord shelter, under specific terms, but was not in a position at the time to move against the Hōjō.[2] The terms were Norimasa's adoption of Kenshin as his heir, the change of name from Kagetora to Terutora (later Kenshin), the title Lord of Echigo, and the Kantō Kanrei post as shogun's deputy.[9][13] In 1552 the Uesugi started to wage war against the Hōjō clan.[3]

Though his rule over the Nagao and Uesugi clan were now unquestioned, much of Echigo was still independent of this young warlord's grasp. Kenshin immediately set out to cement his power in the region, but these efforts were still in their infant stages when far more pressing concerns appeared. Ogasawara Nagatoki and Murakami Yoshikiyo, two Shinano lords, both appeared before Kenshin requesting his help in halting the advances of the powerful warlord Takeda Shingen.[13] Around the time Kenshin became the new lord of Echigo, Shingen had won major victories in Shinano Province. With the Takeda's conquests taking them remarkably close to the borders of Echigo, Kenshin agreed to take the field on two fronts,[3] however the conflicts between the three lords showed also various alliances and treaties.[14]

Kenshin's military success is related to his successful reform efforts on trade, market, transportation network (taxing mechanism in the port towns), and revenues generated by the cloth trade.[15] The result was control over commerce which previously government did not have. He also established feudal ties with the warrior population by land grants.[16] The so-called Funai Statutes show the provisions that apply to the traditional elites and common folk, tax breaks due to war exhaustion, with intent to centralize and consolidate the lands around his capital, which were followed by further reforms for the consolidation of the imperial lands prior the 1560–1562 Kantō campaign. However, despite Kenshin's control over agriculture and economy, he did not thoroughly implement key reforms such as cadastral surveys, important for military obligations, implying Kenshin's focus on commerce. The management of the administration, military organization, as well in some minor battles in Echigo Funai were handed by vassal Kurata Gorōzaemon.[17][18]

Conflict with Takeda Shingen

What followed was the beginning of a rivalry which became legendary. In the first conflict between the two, both Uesugi Kenshin and Takeda Shingen were very cautious, only committing themselves to indecisive skirmishes. Over the years, there would eventually be a total number of five such engagements at the famous site of Kawanakajima (1553–1564),[19] though only the fourth would prove to be a serious, all-out battle between the two.[20]

In 1561, Kenshin and Shingen fought the biggest battle they would fight, the fourth battle of Kawanakajima. Kenshin used an ingenious tactic: a special formation where the soldiers in the front would switch with their comrades in the rear, as those in the frontline became tired or wounded. This allowed the tired soldiers to take a break, while the soldiers who had not seen action would fight on the front lines. This was extremely effective and because of this Kenshin nearly defeated Shingen. In Kōyō Gunkan there is one of the most famous instances of single combat in samurai history; during this battle, Kenshin managed to ride up to Shingen and slashed at him with his sword. Shingen fended off the blows with his iron war fan or tessen. Kenshin failed to finish Shingen off before a Takeda retainer drove him away. Shingen made a counter-attack and the Uesugi army retreated.[21][22] The result of the fourth battle of Kawanakajima is still uncertain. Many scholars are divided on who the actual victor was, if the battle was actually decisive enough to even declare one, thus is generally considered a draw.[23][24] It is considered to be the largest casualty battle in the Sengoku period,[25] with loss of estimated 72 percent of Kenshin's army and 62 percent of Shingen's army, but Shingen also lost two of his most important generals during the battle, namely his advisor Yamamoto Kansuke and younger brother Takeda Nobushige. Some more conservative estimates place the casualties around 20 percent.[24]

In addition, there was an incident when the Hōjō boycotted salt supplies to Kai Province. When Kenshin heard of Shingen's problem he sent salt to the Shingen from his own province. Kenshin commented that the Hōjō had "performed a very mean act". Kenshin added, "I do not fight with salt, but with the sword".[10][20] His respect for Shingen is evident from when he died Kenshin privately wept and stated, "I have lost my good rival. We won't have a hero like that again!"[10]

Though his rivalry with Takeda Shingen was legendary, Uesugi Kenshin actually had a number of other ventures occurring around the times of these famous battles (1553–1564). In the year 1559, he made a trip with escort of 5000 men to pay homage to the shogun in Kyoto.[26] This served to heighten his reputation considerably, and added to his image as a cultured leader as well as a warlord. This same year he was pushed once again by Uesugi Norimasa to take control of the Kantō back from the Hōjō, and in 1560 he was able to comply. In August of the same year, he put southern Echigo under control of five man council for the broad mobilization, as well formed small investigative council for any kind of unrest.[27] Heading a campaign against the Hōjō Ujiyasu from fall 1560 to the summer of 1561, Kenshin was successful in taking a number of castles from the clan, like Numata and Umayabashi castles,[28] which ended with the first siege of the Odawara Castle in Sagami Province. He managed to break the defenses and burn the town, but the castle itself remained unconquered due to threats from Shingen,[29] and thus seized Kamakura.[30] In 1561, Kenshin saved his ally Ōta Sukemasa who was under siege by both Ujiyasu and Shingen, while in November 1569 when Shingen sieged Odawara Castle, Ujiyasu requested help from Kenshin.[9]

The other main area which interested Uesugi Kenshin was Etchū Province in the west, and Kenshin would spend nearly half his life involved in the politics of that province. The land was inhabited by two feuding clans, the Jinbo and the Shiina clan. Kenshin first entered the dispute as a mediator in the early 1550s between rivals Shiina Yasutane and Jinbo Nagamoto, but he later sided with the Shiina and took over the Jinbo clan. Decades later, Kenshin turned against the Shiina clan, taking their main castle in 1575 and having Shiina Yasutane assassinated in 1576 by Kojima Motoshige. At this point, by 1564 Kenshin controlled both Etchū and Kōzuke Province.[3]

Conflict with Oda Nobunaga

By the 1570s, Kenshin governed Echigo, some adjacent provinces, all Hokuriku seaboard, and routed Nobunaga's forces in Echizen Province.[31] In 1571, Kenshin attacked Shingen's satellite Ishikura Castle in Kōzuke province, and they again faced each other at the Battle of Tonegawa, to once again disengage.[32]

Starting in the year 1576, Kenshin began to consider the issue of Oda Nobunaga, who had since grown to be Japan's most powerful warlord of the time. With both Takeda Shingen and Hōjō Ujiyasu dead, Kenshin was no longer blocked off from this realm of expansion. So, when the death of a lord in Noto Province sparked up confusion and conflict, Kenshin was quick to use the opportunity, taking land from the weakened clan which put him in a position to threaten Nobunaga and his allies. In response, Nobunaga pulled together his own forces and those of his two best generals; Shibata Katsuie (柴田勝家) and Maeda Toshiie (前田利家) to meet Kenshin, who successfully besieged Nanao Castle,[33] at Tedorigawa (1577) in Kaga Province. Kenshin based his 30,000 strong army at the castle of Matsuto, while Nobunaga arrived with 50,000 troops led by many famous generals.[34]

Despite Nobunaga's overwhelming numbers, Kenshin managed to score a solid victory on the field. At first, Kenshin anticipated that Nobunaga will try to move by night over the river for dawn attack and thus refused to engage the Nobunaga army. Then he pretended to send forth a small unit to attack Nobunaga's main force from behind and gave his enemy a great opportunity to crush his remaining force. Nobunaga took the bait. Nobunaga's force attacked at night expecting a weakened opponent at the front; instead Kenshin's full military might was waiting.[34][3] However, Kenshin who described the opponent's performance as "surprisingly weak", had a false impression to have defeated Nobunaga, as his army was actually led by Katsuie.[35]

Death

In October 1577, Uesugi Kenshin arranged to put forth a grand army to continue his assaults into Nobunaga's land. In 1578 entered alliance with Takeda Katsuyori against Nobunaga,[28] but held up by bad weather, he died of a esophageal cancer in the spring of 1578.[36] His death poem was:

Even a life-long prosperity is but one cup of sake; A life of forty-nine years is passed in a dream; I know not what life is, nor death. Year in year out-all but a dream. Both Heaven and Hell are left behind; I stand in the moonlit dawn, Free from clouds of attachment.[37]

The cause of Kenshin's death has been questioned throughout the years. The theory accepted by most scholars is that early sources record his deterioration of health condition, his complaints of pain in the chest "like an iron ball", and as Kenshin Gunki (1582) records "on the 9th day of the 3rd month he had a stomach ache in his toilet. This unfortunately persisted until the 13th day when he died".[36] However, it is also speculated that he was victim of one of the most famous ninja assassinations; a ninja been waiting in the cesspool beneath the latrine at Kenshin's camp with a short spear or sword.[38] The theories are not mutually exclusive — the assassin, if he existed, and was possibly sent by Nobunaga, might simply have fatally wounded an already-dying man. However, as his anticipation of own death is recorded in the death poem, the possibility of the assassination is less likely.[36]

Domestically, Kenshin left behind a succession crisis. While he never had any children of his own, Kenshin adopted two boys during his lifetime. His nephew, Uesugi Kagekatsu, was probably adopted for deflection of the antagonism by Kagekatsu's father, Nagao Masakage, relatives and supporters. Another adopted son, Uesugi Kagetora, who was originally the son of Hōjō Ujiyasu,[3] was adopted to secure the Echigo's borders.[39] Some suppose that Kagekatsu was intended to be gradually set up as his heir,[39] while others that Kenshin decided to divide the estates between the two.[40]

Both sons had external blood ties, and reasonable claims. Kagetora was besieged at Ōtate in 1578, and although contacted for aid Hōjō Ujimasa and Takeda Katsuyori, the former backed down, Kagekatsu married his sister, and eventually was able to secure his succession. Kagetora fled to a castle near the Echigo-Shinano border where he committed suicide in 1579.[40][41]

The death caused local power struggles, with the result of almost decade long infighting in Echigo between 1578–1587, usually divided into "Otate Disturbance" (1578–1582) and "Shibata rebellion" (1582–1587).[42] The resistance of the Kagetora's supporters continued for few years in north-central Echigo.[41] In 1582, Shibata Shigeie, who was a vassal of Kagekatsu, led a rebellion in north Echigo, probably due to low rewards for his support of Kagekatsu, but even more the Kagekatsu's granting control over the toll barriers in the port of Niigata to Takemata Yoshitsuna.[43]

However, in the aftermath of the costly internal struggle, the Oda clan exploited rebellions against Kagekatsu to advance right up to the border of Echigo, having captured Noto and Kaga while the Uesugi brothers were busy with the infighting. This combined with the destruction of the Takeda clan, Uesugi's then ally and long time Oda enemy, would come close to destroying the Uesugi clan before Oda Nobunaga's own death once again shattered the balance of power in Japan.[44]

Honours

- Junior Second Rank (September 9, 1908; posthumous)

Kenshin Festival

The Kenshin Festival 謙信公祭 (Kenshin Kousai) takes place every August in Jōetsu since 1926. The procession starts at Kasugayama Castle for the reenactment of the fourth Kawanakjima battle, with an army of 400–1000 soldiers.[45][46] Japanese singer-songwriter Gackt portrayed Kenshin on several occasions since 2007, and thanks to his participation, the festival in 2015 reached record high attendance of 243,000 people.[47][48]

In popular culture

The 1990 Japanese film Heaven And Earth (original title: Ten to Chi to) directed by Haruki Kadokawa,[49] covers the rivalry between Uesugi Kenshin and Takeda Shingen, focusing mainly on the character of Kenshin who is referred to by his original name Kagetora.[50] The film has been praised for its realistic depictions of warfare and battles of the period. It is also famous for holding the world record for most saddled horses used in one sequence — 800 horses were in a battle segment.[51]

In the 2007 NHK Taiga drama, Fuurin Kazan, Uesugi Kenshin is portrayed by Japanese singer-songwriter Gackt. The 2009 NHK Taiga drama Tenchijin tells the story of Uesugi Kenshin, although its main focus is on Naoe Kanetsugu, the page and later advisor to Uesugi Kenshin's adopted son and heir Uesugi Kagekatsu.

Kenshin was again voiced by Gackt in the anime of the gag manga, Tono to Issho (2010–2011). The live action drama Sengoku Basara: Moonlight Party cast actress Mayuko Arisue as Kenshin.

Preceding this, Kenshin was voiced in both the Sengoku Basara games and anime by a female voice actress and has a very feminine appearance throughout the series.

Kenshin has been featured in many video games, such as the Koei's Samurai Warriors and Warriors Orochi series. He is a playable character in Pokémon Conquest (Pokémon + Nobunaga's Ambition in Japan), where he is the warlord of Illusio with his partner Pokémon being Gallade and Mewtwo.[52]

Quotes

Fate is in heaven, armor is on the chest, accomplishment is in the feet; always fight with your opponent in the palm of your hand, and you won't get wounded. If you fight willing to die, you'll survive; if you fight trying to survive, you'll die. If you think you'll never go home again, you will; if you hope to make it back, you won't. While it is not incorrect to consider the world uncertain, as a warrior one should not think of it as uncertain but as totally certain.[53]

Gallery

Kenshin's armour

Kenshin's armour Kenshin's mythical riding into battle by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1883)

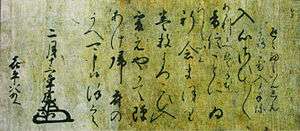

Kenshin's mythical riding into battle by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1883) Kenshin writing his death poem, by Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

Kenshin writing his death poem, by Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

See also

References

- 1 2 Trevor Nevitt Dupuy; Curt Johnson; David L. Bongard (1992). Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography. HarperCollins. p. 765. ISBN 978-0-06270-015-5.

- 1 2 Turnbull, Stephen (1987). Battles of the Samurai. Arms and Armour Press. p. 41,44. ISBN 0853688265.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Turnbull 2012, p. 53.

- ↑ Turnbull 1998, p. 13, 89, 295.

- ↑ Cleary 2008, p. 268.

- ↑ Ōta 2011, p. XV.

- ↑ Sansom, George (1961). A History of Japan, 1334–1615. Stanford University Press. pp. 246, 288. ISBN 0804705259.

- ↑ Turnbull 1998, p. 153.

- 1 2 3 Turnbull 1998, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Sato, Hiroaki (1995). Legends of the Samurai. Overlook Duckworth. pp. 210–213, 225, 221. ISBN 9781590207307.

- ↑ Goldsmith 2008, p. 182.

- ↑ Goldsmith 2008, p. 183.

- 1 2 Turnbull 2013, p. 119.

- ↑ Turnbull 1998, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Goldsmith 2008, pp. 179–181, 186, 192, 194.

- ↑ Goldsmith 2008, pp. 186–187, 230.

- ↑ Goldsmith 2008, pp. 197–221, 230, 248.

- ↑ Hall, Jansen 2015, p. 191.

- ↑ Turnbull 1998, pp. 212–217.

- 1 2 Turnbull 2013, p. 120.

- ↑ Turnbull 1998, pp. 269–272.

- ↑ Victoria Charles (2012). Art of War. Parkstone International. p. 124. ISBN 9781780428765.

- ↑ Turnbull 1998, p. 272.

- 1 2 Goldsmith 2008, p. 219.

- ↑ Turnbull 1998, p. 269.

- ↑ Goldsmith 2008, p. 196.

- ↑ Goldsmith 2008, p. 211.

- 1 2 Turnbull 1998, p. 89.

- ↑ Turnbull 1998, p. 216.

- ↑ Goldsmith 2008, pp. 197–215.

- ↑ Goldsmith 2008, p. 230.

- ↑ Turnbull 1998, p. 221.

- ↑ Ōta 2011, p. 403.

- 1 2 Turnbull 1998, p. 228.

- ↑ Ōta 2011, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 Turnbull 2012, p. 32.

- ↑ Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki (1993). Zen and Japanese Culture. Princeton. p. 82.

- ↑ Turnbull 2012, pp. 53–54.

- 1 2 Goldsmith 2008, p. 233.

- 1 2 Turnbull 1998, p. 230.

- 1 2 Goldsmith 2008, p. 234.

- ↑ Goldsmith 2008, p. 231.

- ↑ Goldsmith 2008, p. 235.

- ↑ Ōta 2011, pp. 9–15.

- ↑ "GACKT謙信、400人の武者を引き連れ出陣 上越市「謙信公祭」" (in Japanese). Oricon. August 23, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ↑ "【イベントレポート】出陣行列・川中島合戦の再現に、GACKT謙信登場". Barks (in Japanese). Japan Music Network. August 23, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ↑ "過去最高24万3000人 第90回謙信公祭の入り込み発表". Joetsu Town Journal (in Japanese). August 24, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ↑ "謙信公祭入り込み数、過去最多24万3200人GACKTさんメッセージ、「来年も楽しみに」". Joetsu Times (in Japanese). August 24, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Ten To Chi To". IMDB.

- ↑ Heaven and Earth (1990 film)

- ↑ "Ten To Chi To - Trivia". IMDB.

- ↑ "Kenshin + Mewtwo". Pokemon Conquest. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

- ↑ Cleary 2008, p. 196.

Sources

- Stephen Turnbull (1998). The Samurai Sourcebook. Cassell & Co. ISBN 1854095234.

- Brian Goldsmith (2008). Amassing Economies: The Medieval Origins of Early Modern Japan, 1450--1700. ProQuest. ISBN 9780549851158.

- Thomas F. Cleary (2008). Training the Samurai Mind: A Bushido Sourcebook. Shambhala Publications. p. 9781590305720.

- Gyūichi Ōta (2011). The Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga. BRILL. ISBN 9789004201620.

- Stephen Turnbull (2012). Samurai Commanders (1): 940–1576. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781782000426.

- Stephen Turnbull (2012). Ninja AD 1460–1650. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781782002567.

- Stephen Turnbull (2013). The Samurai: A Military History. Routledge. ISBN 9781134243693.

- John Whitney Hall; Marius B. Jansen (2015). Studies in the Institutional History of Early Modern Japan. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400868957.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Uesugi Kenshin. |

| Preceded by Uesugi Norimasa |

Uesugi family head 1548-1578 |

Succeeded by Uesugi Kagekatsu |