Keelung Campaign

| Keelung Campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Sino-French War | |||||||

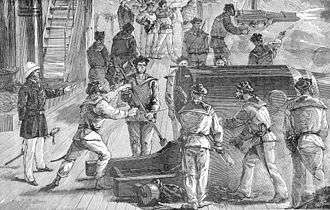

French forces land at Keelung, 1 October 1884 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

20+ warships 4,500 infantry by March 1885) | 35,000 infantry by March 1885 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~700 dead, several hundred wounded | Several thousand killed and wounded | ||||||

The Keelung Campaign (August 1884–April 1885) was a controversial military campaign undertaken by the French in northern Formosa (Taiwan) during the Sino-French War. After making a botched attack on Keelung in August 1884, the French landed an expeditionary corps of 2,000 men and captured the port in October 1884. Unable to advance beyond their bridgehead, they were invested inside Keelung by superior Chinese forces under the command of the imperial commissioner Liu Mingchuan. In November and December 1884 cholera and typhoid drained the strength of the French expeditionary corps, while reinforcements for the Chinese army flowed into Formosa via the Pescadores Islands, raising its strength to 35,000 men by the end of the war. Reinforced in January 1885 to a strength of 4,500 men, the French won two impressive tactical victories against the besieging Chinese in late January and early March 1885, but were not strong enough to exploit these victories. The Keelung campaign ended in April 1885 in a strategic and tactical stalemate. The campaign was criticised at the time by Admiral Amédée Courbet, the commander of the French Far East Squadron, as strategically irrelevant and a wasteful diversion of the French navy.

Background

Following the defeat of China's Guangxi Army by the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps in the Bac Ninh campaign (March 1884), a two-year confrontation between France and China in northern Vietnam was ended on 11 May 1884 by the conclusion of the Tientsin Accord, under which the Chinese undertook to withdraw their troops from Vietnam and to recognise a French protectorate in Tonkin. However, the hopes aroused by this agreement, which seemed to have brought France's Tonkin campaign to a victorious end, were shattered on 23 June 1884 by the Bac Le ambush, in which a French column advancing to occupy Lang Son and other frontier towns was attacked near Bac Le by a detachment of the Guangxi Army.

When news of the 'Bac Le Ambush' reached Paris, there was fury at what was perceived as blatant Chinese treachery. Jules Ferry's government demanded an apology, an indemnity, and the immediate implementation of the terms of the Tientsin Accord. The Chinese government agreed to negotiate, but refused to apologise or pay an indemnity. The mood in France was against compromise, and although negotiations continued throughout July, Admiral Amédée Courbet, the commander of France's newly created Far East Squadron, was ordered to take his ships to Foochow. He was instructed to prepare to attack the Chinese fleet in the harbour and to destroy the Foochow Navy Yard. Meanwhile, as a demonstration of what would follow if the Chinese remained recalcitrant, Courbet was ordered on 2 August to despatch a naval force to the port of Keelung in northern Formosa, destroy its coastal defences, and occupy the town as a 'pledge' (gage) to be bargained against a Chinese withdrawal from Tonkin.[4]

Failed French landing at Keelung, August 1884

French interest in Keelung dated from February 1884, when Admiral Sébastien Lespès, the commander of France's Far East naval division, had recommended its occupation in the event of a war between France and China on the grounds that it could be easily seized and easily held. When this recommendation was made, Keelung was poorly defended. As tension between France and China grew in July 1884 the garrison of Keelung was substantially increased and the town's defences improved, and in August 1884 it was no longer the easy target it had been six months earlier. Its inner harbour was defended by three shore batteries: the recently completed Ta-sha-wan Battery (大沙灣砲台), boasted by the Chinese to be impregnable; the Ehr-sha-wan battery on the eastern side of the harbour; and a third battery on the seaward slope of Mount Clement (Huo-hao-shan, 火號山), a prominent hill to the west of the town. By the end of July 1884 there were 5,000 Chinese soldiers stationed in northern Formosa, deployed around the ports of Keelung and Tamsui. The appointment of Liu Mingchuan as imperial commissioner for Formosa in July 1884 also underscored the determination of the Qing government to defend Formosa. Liu was a veteran military commander, who had distinguished himself in the Taiping Rebellion.

Liu Mingchuan was aware that Keelung and the nearby port of Tamsui were likely targets for a French attack, and made sensible defensive dispositions to oppose a landing at both towns. He stationed 2,500 Chinese troops around Keelung, the likeliest target, under the command of the generals Sun Kaihua and Su Desheng,[lower-alpha 1] while he himself remained with the other half of his army at Tai-pak-fu (modern Taipei), occupying a central position that would allow him to move quickly either to Tamsui or to Keelung once the French threat developed.[5]

Admiral Courbet, then aboard the French cruiser Volta in the Min River, received the French government's order to attack Keelung on the evening of 2 August. He entrusted this mission to Admiral Lespès, his second-in-command, who left the Min River the following morning aboard the gunboat Lutin to meet the ironclads Bayard and La Galissonnière off the island of Matsu. At Matsu, Lespès transferred Bayard's landing company to his flagship La Galissonnière, and on the night of 3 August crossed the Formosa Strait with La Galissonnière and Lutin. The two French ships arrived off Keelung on the morning of 4 August, where the cruiser Villars was already waiting for them.[6]

On the morning of 5 August, after the Chinese rejected a French ultimatum to hand over their coastal defences, La Galissonnière, Villars and Lutin engaged and disabled Keelung's three coastal batteries. Admiral Lespès put a landing force ashore in the afternoon to occupy Keelung and the nearby coal mines at Pei-tao (Pa-tou, 八斗), but the arrival of a large body of Chinese troops led by Liu Mingchuan forced the French to make a fighting withdrawal and re-embark on 6 August. French casualties in this unsuccessful operation were 2 dead and 11 wounded. The Chinese suffered markedly heavier casualties.[7]

French strategic debate, September 1884

In the wake of the Battle of Foochow (23 August 1884), which inaugurated the nine-month Sino-French War, the French decided to make a second attempt to put pressure on China by seizing Keelung. Admiral Courbet argued vigorously against a campaign in Formosa and submitted alternative proposals for a campaign in northern Chinese waters to seize either Port Arthur or Weihaiwei. He was supported by Jules Patenôtre, the French minister to China.[8]

Courbet's proposals, although militarily attractive, were too ambitious for the French government to stomach. The French premier Jules Ferry fought the Sino-French War in the teeth of parliamentary disapproval, and was unable to give Courbet the resources necessary for a major campaign on the Chinese mainland. A limited operation to seize Keelung, on the other hand, could be undertaken with the forces already at Courbet's disposal. The town could be taken and held by a relatively small French force, and with its nearby coal mines would make an admirable wartime base for the Far East Squadron. A victory at Keelung would also avenge the failure of 6 August. The decision to attack Keelung was made by the French cabinet on 18 September 1884. For good measure, the cabinet also sanctioned an attack on nearby Tamsui, provided that the town could be captured without damage to European commercial interests.[9]

French capture of Keelung, 1 October 1884

On 1 October 1884 Lieutenant-Colonel Bertaux-Levillain landed at Keelung with a small expeditionary corps (2,250 men) drawn from the French garrisons in Tonkin and Cochinchina. The Formosa Expeditionary Corps (French: corps expéditionnaire de Formose) consisted of three four-company battalions of marine infantry (chefs de bataillon Ber, Lacroix and Lange), a marine artillery battery, and a scratch battery of two 80-millimetre mountain guns and 4 Hotchkiss canons-revolvers.[lower-alpha 2] A small force of Vietnamese porters accompanied the combatants.[10]

The men of the expeditionary corps sailed from Saigon and Along Bay in the third week of September aboard the state transports Nive, Tarn and Drac and joined the Far East Squadron off the island of Matsu on 29 September. The three troopships were escorted on the final leg of their journey by the ironclad Bayard. On the morning of 30 September the invasion force arrived off Keelung. Courbet scouted the Chinese defences during the afternoon, and gave orders for an opposed landing on the following morning.[11]

At dawn on 1 October Ber's marine infantry battalion was put ashore to the west of Keelung, at the foot of Mount Clement. Supported by naval gunfire from several ships of Courbet's Far East Squadron, the French scaled Mount Clement and established a defensive position on its summit, flanking the Chinese out of their positions to the south of Keelung and threatening their line of retreat to Tamsui. French casualties in the battle for Mount Clement were negligible: 4 killed and 12 wounded. Chinese casualties, according to Formosan informants, were around 100 killed and 200 to 300 wounded. In the first week of October the French occupied several hills in the immediate vicinity of Keelung and began to fortify them. However, the expeditionary corps was too small to advance beyond Keelung, and the Pei-tao coal mines remained in Chinese hands.[12]

Liu Mingchuan had commanded the unsuccessful defence of Keelung in person, with a Chinese division of 2,000 troops. Anticipating that the French would follow up their success with a landing at Tamsui, he left half of his force in strong defensive positions around Lok-tao (Chinese: 六堵; pinyin: Liù-dǔ), astride the road to Tamsui, and retreated to Tai-pak-fu with the rest on 3 October. It was rumoured that he intended to flee south to Tek-cham (Hsinchu), and his arrival in Tai-pak-fu was greeted with rioting. Several of his bodyguards were killed and he himself was arrested and held for several days in the city's Lungshan temple.[13]

Liu Mingchuan took measures to reinforce Tamsui, in the river nine torpedo mines were planted and the entrance was blocked with ballast boats filled with stone which were sunk on September 3, matchlock armed "Hakka hill people" were used to reinforce the mainland Chinese battalion, and around the British Consulate and Customs House at the Red Fort hilltop, Shanghai Arsenal manufactured Krupp guns were used to form an additional battery.[14]

At Tamsui, the entrance of the river had been closed by laying down six torpedoes in the shape of a semi-circle on the inside of the bar. The Douglas steamers Fokien and Hailoong running to the port, as well as the German steamer Welle, were, whenever necessary, piloted over the torpedoes by the Chinese who had laid them down. The mandarins engaged in planting the guns that had been brought to the island by the latter steamer.Trade was resumed during the middle of the month at Twatutia, it being regarded for the time as safe, and the country thereabouts had quieted down to such an extent that a good deal of tea was brought in. Life for the foreigners was very much cramped. They were prohibited from making trips into the country; and even in the settlement, with religious processions, crackers, and, gongs going at all times of day, and the watchmen making a great noise with bamboos all night, rest was well nigh impossible except to the Chinese guards told off to protect foreign hongs, who after disappearing all day, except at meal times, "return at night, and instead of guarding the property, turn in early and sleep as soundly as Rip van Winkle did till morning."

Under the impression that the French would attempt to enter the Tamsui river, ballast boats and junks loaded with stones were sunk at the entrance. A number of Hakka hillmen were added to the government force. They were armed with their own matchlocks, which in their ignc ranee they preferred to foreign rifles. Much was expected of them, as the life of warfare they had led on the savage border had trained them to be good shots and handy with their knives. By the end of August the French had succeeded in holding the shore line at Kelung, but were unable to advance beyond it; and as Chinese soldiers had for some days been erecting earthworks and digging entrenchments on the hills on the east side of the bay overlooking the shipping, the French sent word ashore for the Europeans to come on board the Bayard, as they intended opening fire on the earthworks which were now just visible.1 The firing was not successful either that day or the next, the nature of the country being in favor of the Chinese; and for many days the shelling was a regular event, the Chinese not apparently suffering much damage themselves, or being able to inflict any upon the French. This condition of affairs continued through September, the French having gained only the summits of the near hills surrounding the harbor.

General Liu Mingchuan left Kelung on the 9th to visit Tamsui and Taipehfu. On his arrival at the latter place he was met at the wharf by some 200 soldiers, 5 buglers, and 2 or 3 drummers. The march up the street with the soldiers in front, the band next, and the general in the rear in his chair, made an imposing parade. His presence is also said to have had a most stimulating effect on the soldiers on guard in the foreign hongs. All appeared in full force with uniforms and rifles, although for several days the muster in one hong had produced only one soldier and a boy in a soldier's coat.

Liu Ming-chuan with some 6,000 men was stationed at Taipehfu in the Banka plain, while the forces at Hobe were daily strengthened, until, in the middle of October, there were assembled about 6,000 men in the neighborhood. Among these were new levies of Hakka hillmen. They were considered by the foreigners to be a dangerous lot to have in the neighborhood, and as they did not speak the same language as the general and other officers, it was feared that misunderstandings might arise with serious results. The other soldiers present were principally northern men, and were said to be well armed. The Hakkas, although armed with their primitive matchlocks, were considered to be brave men and were hardened to the privations of warfare. Their matchlocks are described as long-barrelled guns, fixed into semi-circular shaped stocks, with pans for priming powder, and armlets made of rattan, worn around the right wrist and containing pieces of bark-cord, which, when lighted, would keep alight for hours, if necessary. When in action the Hakka pours a charge of powder down the muzzle; on top of that are dropped two or three slug shot or long pieces of iron, withouL wadding. The trigger is made to receive the lighted piece of bark, and when powder covers the priming pan and all is ready, • the trigger is pulled and if,—if the weather is dry, off goes the gun. The ordinary method of handling these weapons is to place the lower end of the butt against the right breast, high enough to enable the curved end to rest against the cheek, and the eye to look down the large barrel, upon which there are ordinarily no sights. This method is sometimes varied by discharging the guns from the hip, and it is quite customary for the Hakka to lie flat on his back, place the muzzle between his toes, and, raising his head sufficiently to sight along the barrel, to take deliberate aim and fire. He is able to make good practice; while his presence, especially when surrounded by rank grass, is decidedly difficult to determine.Rev. Dr. Mackay's Tamsui Mission Hospital, with Dr. Johansen in charge, which had rendered such great services to the Chinese wounded and had no doubt been the means of saving many lives, was visited on the 19th by General Sun, who thanked the doctor in charge as well as Dr. Browne of the Cockcliafer (who had given valuable assistance) for their attentions to the sick and wounded. The patients then numbered only a dozen, a good many of the wounded having left, fearing that the French might land again and kill them; others, seeing their wounds healing nicely, went away into the town. One man who had been shot through the left shoulder, in the region of the collar bone, after a week or ten days' treatment suddenly shouldered his rifle and left for the front, preferring life with his comrades to being confined in the hospital. It was supposed that the bullet had pierced the upper part of his lungs. Another instance occurred seven days after the French landing, when a Chinese walked into the hospital with his skull wounded and the brain visible. Several others, shot through the thighs and arms, bones being splintered in many pieces, bore their pain most heroically. Soon after the engagement, when there were seventy men in the hospital, some being badly wounded with as many as three shots apiece, there was scarcely a groan to be heard. One of the wounded came to the hospital after having had a bullet in his calf for nine or ten days. Dr. Browne extracted the bullet, and off the man went back to the front. Many other instances like the foregoing might be recorded, all of which indicated that the Chinese could recover in a few days from wounds, which, if not actually fatal, would have laid foreign soldiers up for months.

— James W. Davidson, The island of Formosa, past and present, [16]

French defeat at Tamsui, 8 October 1884

Meanwhile, after an ineffective naval bombardment on 2 October, Admiral Lespès attacked the Chinese defences at Tamsui with 600 sailors from the French squadron’s landing companies on 8 October. Tamsui had a large foreign population at this period, and many of the town's European residents formed picnic parties and flocked to vantage points on the nearby hills to watch the unfolding battle.[17]

The French attack soon began to falter. The French fusiliers-marins were not trained to fight as line infantry, and were attacking over broken ground. Capitaine de frégate Boulineau of Château-Renaud, who had replaced the officer originally scheduled to command the attack at the last moment, lost control of his men in the thick undergrowth in front of the Chinese forts. The French line gradually lost its cohesion and ammunition began to run short. The Chinese forces at Tamsui, numbering around 1,000 men, were under the command of the generals Sun Kaihua and Zhang Gaoyuan.[lower-alpha 3] Seeing the French in confusion, Sun Kaihua advanced with his own forces and outflanked the French on both wings. The French hastily withdrew to the shore and re-embarked under cover of the squadron's guns. French casualties at Tamsui were 17 dead and 49 wounded. Chinese casualties, according to European employees of the Tamsui customs, were 80 dead and around 200 wounded.[18]

The repulse at Tamsui was one of the rare French defeats in the Sino-French War, and had immediate political significance. China's war party had been placed on the defensive after the loss of China's Fujian fleet in the Battle of Fuzhou on 23 August 1884, but the unexpected Chinese victory at Tamsui six weeks later bolstered the position of the hardliners in the Qing court. The court thereupon decided to continue the war against France until the French withdrew their demand for the payment of an indemnity for the Bac Le ambush, rejecting an American offer of mediation made shortly after the battle. This decision ensured that the Sino-French War would continue for several more months, with increasing losses and expenditure on both sides.

The Chinese took prisoner and beheaded 11 French marines who were injured in addition to La Gailissonniere's captain Fontaine and used bamboo poles to display the heads in public, to incite anti-French feelings in China pictures of the decapitation of the Frenchmen were published in the Tien-shih-tsai Pictorial Journal in Shanghai.[19]

"A most unmistakable scene in the market place occurred. Some six heads of Frenchmen, heads of the true French type were exhibited, much to the disgust of foreigners. A few visited the place where they were stuck up, and were glad to leave it—not only on account of the disgusting and barbarous character of the scene, but because the surrounding crowd showed signs of turbulence. At the camp also were eight other Frenchmen's heads, a sight which might have satisfied a savage or a Hill-man, but hardly consistent with the comparatively enlightened tastes, one would think, of Chinese soldiers even of to-day. It is not known how many of the French were killed and wounded; fourteen left their bodies on shore, and no doubt several wounded were taken back to the ships. (Chinese accounts state that twenty were killed and large numbers wounded.)In the evening Captain Boteler and Consul Frater called on General Sun, remonstrating with him on the subject of cutting heads off, and allowing them to be exhibited. Consul Frater wrote him a despatch on the subject strongly deprecating such practices, and we understand that the general promised it should not occur again, and orders were at once given to bury the heads. It is difficult for a general even situated as Sun is—having to command troops like the Hillmen, who are the veriest savages in the treatment of their enemies—to prevent such barbarities.

"It is said the Chinese buried the dead bodies of the Frenchmen after the engagement on 8th instant by order of General Sun. The Chinese are in possession of a machine gun taken or found on the beach.

— James W. Davidson, The island of Formosa, past and present, [20]

Actions around Keelung, November and December 1884

As a result of the defeat at Tamsui, French control over Formosa was limited merely to the town of Keelung and to a number of positions on the surrounding hills. This achievement fell far short of what had been hoped for, but without reinforcements the French could go no further. They therefore did their best to fortify the precarious bridgehead at Keelung. Several forts were built to cover the various approaches to the town. Fort Clement, Fort Central and Fort Thirion faced west towards the Chinese positions at Lok-tao. Fort Tamsui and Eagle's Nest (Nid d'aigle) covered the approach to Keelung from the southwest along the main road from Tamsui. Cramoisy Pagoda, a large Chinese house converted into a fort and manned by Captain Cramoisy's marine infantry company, covered the southern approach to Keelung. Fort Ber, Fort Gardiol and Fort Bayard, a chain of forts collectively known as the 'Ber Lines', crowned the low range of hills that screened Keelung's eastern suburb of Sao-wan. The three Chinese forts disabled by the French in August were repaired and named respectively Fort Lutin, Fort Villars and Fort La Galissonnière, after the three ships that had engaged them.[21]

On 2 November 1884 the Chinese general Cao Zhizhong[lower-alpha 4] attacked the French outposts of Fort Tamsui and Eagle's Nest to the southwest of Keelung with a force of 2,000 men. The attackers made a night march from Tsui-tng-ka (水返腳, now Hsichih, 汐止), hoping to take the French by surprise with a dawn attack, but failed to reach their positions in time. The Chinese attack was made in daylight and was easily repelled by the French, who mowed down the attackers with Hotchkiss and rifle fire. The Chinese admitted to a loss of 200 men in the attack, but the true figure was probably somewhat higher. One French soldier was lightly wounded. On 3 November a force of Chinese marauders approached Keelung from the south and tried to rush Cramoisy Pagoda, but were repelled without difficulty by its defenders. The attack was probably made by the Chinese in the hope that the French had lowered their guard after the failure of the previous day's assault.[22]

Following the failure of these attacks Liu Mingchuan began to invest Keelung. He ordered the town's inhabitants to leave their homes, thereby denying the French their services as cooks, laundrymen and labourers, and he fortified a number of hill positions to the south and southeast of Keelung. The Chinese built major forts on the summits of Shih-ch'iu-ling (獅球嶺), Hung-tan-shan (紅淡山) and Yueh-mei-shan (月眉山), linking them with an elaborate trench system. These forts were christened respectively by the French La Dent ('the fang'), Fort Bamboo and La Table. From its distinctive shape, Hung-tan-shan became Le Cirque ('the corry'). On 13 and 14 November the French destroyed the Chinese defences on the summit of Hung-tan-shan and burned the village of Nai-nin-ka (南寧腳) to the southeast of Shih-ch'iu-ling, which the Chinese were using as a supply depot. On 12 December the French captured and partly demolished the Shih-ch'iu-ling fort (La Dent), but were forced to withdraw by a Chinese counterattack. On each occasion the Chinese quickly made good the damage.[23]

Although French losses in these engagements with Liu Mingchuan's army were negligible, the Formosa expeditionary corps suffered heavy casualties from disease. An outbreak of cholera and typhus in November 1884 killed 83 French soldiers by 23 December and incapacitated hundreds more. On 1 December 1884 only 1,100 French soldiers were fit were action, half the number who had landed at Keelung two months earlier. French officers with long memories compared the occupation of Keelung with the siege of Tourane twenty-five years earlier, where an initial victory had been succeeded by a costly and protracted stalemate and, ultimately, an ignominious evacuation by the invaders.[24]

December followed with but little to relieve the monotony. The foreign community, not having received any outside supplies for some months, were now obliged to put themselves on half and three-quarter allowances, besides laying aside something, that their Christmas dinner might not lose by the blockade. The French allowed mails and stores to be landed for the personal use of the consul and the officers and crew of the Cockchafer, but refused to allow anything of like nature to be delivered to the foreign community. This they, of course, had a right to do, but it does seem that they might have acted with a little more generosity under the circumstances, especially as they were using Hongkong for all purposes as a naval supply depot. However, Christmas day was celebrated by the whole Tamsui community with a dinner, in which " huge pieces of beef, lordly turkeys, and fatted capons, home made puddings, pies and cakes" played a leading part. A regatta which had been planned for the day had to be postponed on account of the weather; it took place on the 29th of December, however; the programme including numerous boat races with foreign and native boats, and finishing up with a greased pole with a pig at the top, and the distribution of prizes amounting to $150.During the month no fighting of importance transpired. The Chinese killed a few Frenchmen who were out foraging for bullocks, and the French destroyed one village where a party of their men had been attacked. The friends of the French officer who was killed during the landing having communicated their desire to recover the body, General Liu Mingchuan, with that manliness and generosity which characterized his later days, offered Taels 200 ($150 gold) to any one who would find and produce the body of the dead officer. As a result the head was discovered some days afterwards, but the body could not be identified, it having been buried with others on the downs.

The French no doubt found great difficulty in advancing into the country. The nature of the place was most favorable to the Chinese, the vicinity of Kelung being hilly and full of cover, and the only roads being narrow pathways. Chinese soldiers were scattered about without regard to rank all over the hills, behind rifle pits, or hidden in thick covers, and even up trees, it was said. French soldiers advancing were exposed to the fire of these unseen riflemen, some of whom were adepts at savage warfare. They moved through the long grass, now erect, now on all fours, suddenly raised themselves just high enough to take aim and fire, then lay down again, and crawled away like snakes from the tell-tale smoke, so that they made but poor targets for even the best of the French riflemen.

— James W. Davidson, The island of Formosa, past and present, [25]

French offensive, 25–31 January 1885

Towards the end of 1884 the French were able to enforce a limited blockade of the northern Formosan port of Tamsui and the southern ports of Taiwan-fu (modern Tainan) and Takow (modern Kaohsiung). The blockade was relatively ineffective, and was unable to prevent the Chinese from using the Pescadores Islands as a staging post for landing large numbers of troops in southern Formosa.[26] Substantial drafts from the Hunan and Anhui Armies raised the strength of Liu Mingchuan's defending army to around 25,000 men by the end of the year, and to around 35,000 men in April 1885.

The Chinese forces around Keelung consisted for the most part of regular soldiers from Fukien and from the northern provinces around the Gulf of Petchili. The French considered them to be the cream of the Chinese army. The men were tall and sturdy, and wore a practical dark blue cloth uniform consisting of baggy trousers reaching to mid-calf and a loose shirt decorated with a large scarlet badge inscribed with characters in black indicating their battalion and company. Leggings and felt-soled slippers completed their normal dress, and they were also issued with a light rain cape either of wool or waterproofed with fish paste. Their equipment included German-made belts, scabbards and ammunition pouches (the latter much admired by the French, who replaced their own 1882 pattern pouches whenever they could). Unlike the French, they did not carry haversacks. Most of them were armed with the Lee Model 1879 rifle, though Mausers, Winchesters and Remingtons were also popular and the bodyguards of the senior mandarins were armed, as befitted their prestige, with the latest Hotchkiss carbines. They were abundantly supplied with ammunition.[27]

Liu Mingchuan also raised a corps of local Hakka militia under the command of Lin Chaodong,[lower-alpha 5] and at one point even recruited a band of head-hunting aborigines from the untamed central mountain region of Formosa. These illiterate tribesmen had long been accustomed to raid the peaceful Chinese villages of the plain, and Liu Mingchuan seized the opportunity to divert their warlike energies against the French. In the event, the tribesmen were of little military value to the Chinese. They were armed only with matchlock rifles loaded with stone bullets. Captain Paul Thirion, whose marine infantry company met them in battle during a skirmish on 20 November 1884, claimed that a gang of small boys throwing stones would have put up a better fight.[28]

In early January 1885 the Formosa expeditionary corps was substantially reinforced with two battalions of infantry, bringing its total strength to around 4,000 men. Four of the six companies of the 3rd African Light Infantry Battalion (chef de bataillon Fontebride) arrived in Keelung on 6 January, and all four companies of the 4th Foreign Legion Battalion (chef de bataillon Vitalis) disembarked on 20 January. Command of the expanded expeditionary corps was given to Lieutenant-Colonel Jacques Duchesne (1837–1918), the future French general and conqueror of Madagascar, who had recently made his name in Tonkin by defeating Liu Yongfu's Black Flag Army in the Battle of Yu Oc (19 November 1884) and fighting his way through to the isolated French post of Tuyen Quang.[lower-alpha 6]

The African Battalion reinforcements soon blooded themselves, but not in accordance with Duchesne's plans. On 10 January 1885 a party of 15 bored zéphyrs under the command of Corporal Mourier escaped from their barracks and launched an impromptu attack on Le Cirque. Their aim, apparently, was to capture the Chinese flag floating above the ramparts of Fort Bamboo and bring it back to Keelung. Mourier and his men soon came under fire, and Fontebride was forced to commit all four companies of the battalion one after another to disengage them. By mid-afternoon the entire African Battalion was deployed in line, in the open, halfway up the slopes of Hung-tan-shan, exchanging fire with the Chinese defenders of Fort Bamboo. Courbet and Duchesne, furious at this reckless, unauthorised attack, ordered Fontebride to extricate the battalion immediately. French casualties in this 'reconnaissance' (as Courbet prudently called it in his official report) were 17 dead and 28 wounded. Chinese casualties were almost certainly higher, as their positions were shelled by the French artillery during the engagement. The survivors of Mourier's party (several of them were killed during the attack) were jailed for 60 days.[29]

Two weeks later the French attacked the Chinese lines in a more orderly manner. On 25 January 1885 Duchesne launched an offensive aimed at capturing the key Chinese position of La Table (Yueh-mei-shan). In three days of fighting the French captured the subsidiary position of Fork Y, enabling their artillery to enfilade the main Chinese defences, but on 28 January torrential rain halted the offensive before the French could assault La Table itself. A Chinese counterattack on Fork Y during the night of 31 January was decisively repulsed by the French with rifle fire at point-blank range. French casualties in the actions of 25 to 31 January were 21 dead and 62 wounded, mostly in the Legion and African battalions. Chinese casualties, mostly sustained in the disastrous counterattack on 31 January, probably amounted to at least 2,000 men. The dead included the battalion commander Zhang Rengui,[lower-alpha 7] a bandit chief from Yilan who had contributed a force of 200 militiamen to Cao Zhizhong's command.[30]

Duchesne was anxious to follow up this limited victory with a further attack on La Table, but heavy rain continued throughout February. No serious troop movements were possible during this period. In mid-February the Chinese bombarded the French positions from La Table with Congreve rockets, but without doing any damage. French artillery fired back, and a lucky shot blew up an ammunition dump on La Table. Thereafter the Chinese left the French in peace.[31]

Duchesne decided to occupy Fork Y, as its possession allowed the French to enfilade long stretches of the Chinese trench lines linking their forts on Yueh-mei-shan and Hung-tan-shan, and Legion and zéphyr garrisons took turn and turn about to hold this position during the chills and rains of February. The French troops soon renamed Fork Y Fort Misery:

Our stay at Fort Misery was dreadful. The rain never let up. It pricked our faces like icicles, put out fires we had spent hours lighting, turned our campsite into a bog and washed out the dye from our clothes. The men slept on beds of liquid mud. Their uniforms, filthy and faded, were a disgraceful sight. As for the Annamese coolies, shivering with cold and fever, we could hardly bear to look at them. Most of them were now clad in French hand-me-downs, which they had either filched from the field hospital or been given by kind-hearted soldiers. The unlucky ones, still clad only in a scanty loincloth, wrapped themselves in sheets or blankets to stay as warm as they could.— Garnot, L'expédition française de Formose, [32]

French offensive, 4–7 March 1885

The rain finally stopped on 2 March, and two days later Duchesne launched a second, highly successful offensive. In a series of actions fought between 4 and 7 March, the French broke the Chinese encirclement of Keelung with a flank attack delivered against the east of the Chinese line, defeating Chinese forces under the command of Cao Zhizhong, Wang Shizheng,[lower-alpha 8] and Lin Chaodong, capturing the key positions of La Table and Fort Bamboo, and forcing the Chinese to withdraw behind the Keelung River.[33]

Duchesne committed 1,300 troops to his attack column. The column contained six companies of the 4th Legion and 3rd African battalions and three companies of marine infantry. Artillery support was provided by three guns under the command of Captain de Champglen and by the gunboat Vipère, which took up a position off Pei-tao from which it could bombard the Chinese positions on Yueh-mei-shan and in the Keelung River valley.[34]

On 4 March the French made a bold outflanking march eastwards towards Pei-tao (八堵), occupying the summits of Wu-k'eng-shan (五坑山) and Shen-ou-shan (深澳山).[35]

At dawn on 5 March they descended into the Shen-ou-k'eng (深澳坑) valley and marched southwards to place themselves dead on the flank of the Chinese line. In the early afternoon they scaled Liu-k'eng-shan (六坑山) from the east and laboriously ascended the eastern face of Yueh-mei-shan (月眉山), approaching the Chinese positions without being spotted. Late in the afternoon they captured La Table with a simultaneous frontal and flanking attack, supported by rifle and artillery fire from the French forward positions on Fork Y. The French guns on Fork Y, firing over open sights at a right angle to the axis of the attack, pounded the Chinese positions as the French infantry closed in on La Table, lifting their fire only seconds before the attackers reached the Chinese defences.[36]

On 6 March the attack column, reinforced by two Legion companies previously stationed on Fork Y, paused to resupply with food and ammunition.[37]

On the morning of 7 March the French thrust westwards from Yueh-mei-shan and fought their way to the summit of Hung-tan-shan, where they stormed Fort Bamboo. The attackers were aided by a diversionary attack mounted by Cramoisy's marine infantry company from the Keelung garrison, which had stealthily occupied a hill position to the west of Fort Bamboo during the previous night. Cramoisy's marsouins disclosed themselves as Fontebride's zéphyrs approached Fort Bamboo from the east, disorganising the Chinese defenders with a devastating volley from behind their positions. The hoisting of the French tricolour above Fort Bamboo was greeted by the ships of the Far East squadron lying in Keelung harbour with blasts on their foghorns, and by cheers from the French troops echeloned back along the line of advance on the summits of Yueh-mei-shan and Liu-k'eng-shan.[38]

In the afternoon of 7 March a mixed column of legionnaires, zéphyrs and marine infantry attacked southwards along the ridge of Niao-tsui-chien (鳥嘴尖), against determined enemy resistance. The struggle for Niao-tsui-chien saw the fiercest fighting of the four-day campaign. The Chinese held the peaks, and rolled rocks down on the advancing French. One Chinese infantry unit, concealed in a wood, opened fire on the French at almost point-blank range and inflicted heavy casualties on the 3rd African Battalion. The French eventually pushed the Chinese off the ridges, and just before sunset drove them back through the village of Loan-loan (Nuan-nuan, 暖暖).[39]

Some French troops attempted to cross the Keelung River in abandoned Chinese sampans, but they were promptly recalled by Duchesne, who had no wish to fight a confusing night action south of the river. At nightfall Duchesne halted the pursuit and regrouped his troops on the northern bank of the Keelung River.[40]

On 8 March the French consolidated their positions around Loan-loan. On 9 March the Chinese withdrew from Shih-ch'iu-ling, which could no longer be held with Hung-tan-shan in French hands, and fell back behind the Keelung River.[41]

French casualties in the March offensive were 41 killed and 157 wounded. Chinese losses may have amounted to around 1,500 killed and wounded. The French also captured a battery of modern German Krupp cannon that had been brought into Formosa by the British blockade-runner Waverley and had just been emplaced on La Table. These guns had fired a few rounds during the battle, but the Chinese had been unable to fuse the shells properly and they had failed to explode on impact. Had the French attack been delayed for a few more days, the Chinese might have been able to shell the French out of their forts around Keelung and force them to withdraw behind the hills of the Ber Lines. Duchesne's offensive had been launched in the very nick of time.[42]

The capture of La Table and Fort Bamboo, although it had been bought at a heavy cost, was a remarkable victory for the French. Duchesne's men had been asked to make an arduous approach march of more than 100 kilometres through unfamiliar countryside and then to fight two major battles in the confusing, heavily wooded, mountainous terrain to the south of Keelung. This spectacular feat of arms, perhaps the most impressive French professional triumph of the Sino-French War, was overshadowed at the time by the news of the relief of the Siege of Tuyen Quang on 3 March 1885, and remains largely unknown to this day in France.[43]

On the 3rd of March, preparations were made to attack a fort known to the French as Fort Bamboo, on account of the bamboo stockade that surrounded it. This was on a curiously shaped hill with almost perpendicular sides and a Hat top, at the back of a village known as Wan Wan. It was a most commanding position, and its capture by the French with the small force at their command was most creditable. The French brought 330 men to the attack, and the pathway was so steep that they were forced to use storming ladders. In gaining this pathway and reaching the fortifications, the French were for two miles under fire, but so determined was the charge that the Chinese weakened and finally retreated. The tale is told by a member of the French expedition ; and a young Chinese officer, an Anhui man, is credited with exceptional braver)-. After the Chinese had fled from the field this officer returned with a small squad, which he led without a sign of fear against the French now greatly outnumbering his little band. This gallant charge in the open field was an exhibition of such rare bravery for the Chinese that the French officer in command was much affected and ordered that the enemy should not be fired upon if it could be helped. Hut, regardless of their inferiority in numbers, the Chinese officer and his men did not falter, and it became necessary for the protection of the French troops to give the order to fire a volley to frighten the enemy from the field. As soon as the smoke had cleared away, the French were surprised to find this officer again leading his men to the front. Again did the French fire, and again did the Chinese appear to retreat; but, with an evident determination to conquer or die on the field, the Anhui man again returned for the third time, with scarcely a corporal's guard remaining. With much regret the French officer gave the order to fire, and the brave little band, lacking only in wisdom, met death to a man.— James W. Davidson, The island of Formosa, past and present, [44]

Pescadores campaign, 25–29 March 1885

Duchesne's victory enabled Admiral Courbet to detach a marine infantry battalion from the Keelung garrison to capture the Pescadores Islands in late March. Strategically, the Pescadores Campaign was an important victory, which would have prevented the Chinese from further reinforcing their army in Formosa, but it came too late to affect the outcome of the war.[45]

Final skirmishes around Keelung, March–April 1885

Despite his defeat Liu Mingchuan remained as resilient as ever. In mid-March he began to fortify a new Chinese defensive line south of the Keelung River and along the Lok-tao (Liu-tu, 六堵) and Chit-tao (Ch'i-tu, 七堵) heights to the west of Keelung, covering the approaches to Tai-pak-fu and Tamsui. The news of Duchesne's victory sparked a brief panic in Tai-pak-fu, and militia units were hastily raised to defend the town against a possible French attack.[46]

But the French were not strong enough to advance beyond their bridgehead at Keelung, particularly after the detachments made from the Keelung garrison for the Pescadores Campaign. They contented themselves with occupying Hung-tan-shan and Yueh-mei-shan, replacing Fort Bamboo and La Table with two identically named forts of their own. Two more forts, Fort Bertin and Southern Fort (Fort du Sud), were built above Loan-loan and on the lower slopes of Hung-tan-shan, overlooking the Keelung River.[47]

The Keelung Campaign now reached a point of equilibrium. The French were holding a virtually impregnable defensive perimeter around Keelung but could not exploit their success, while Liu Mingchuan's army remained in presence just beyond their advanced positions. The Chinese attempted to disrupt work on the construction of Fort Bertin, uncomfortably close to their forward positions, and there were one or two minor skirmishes around the new fort in late March in which several French soldiers were wounded. However, neither the French nor the Chinese undertook any major operations. During the first fortnight of April the French and Chinese outposts occasionally exchanged shots, but no casualties were suffered by either side.[48]

At the end of March 1885 French reverses in Tonkin overshadowed Duchesne's achievement at Keelung. The shocking news of Lieutenant-Colonel Paul-Gustave Herbinger’s retreat from Lang Son on 28 March reached Courbet at Makung on 4 April 1885, in the form of a navy ministry despatch brought from Hong Kong by the cruiser Roland. Courbet was ordered to evacuate Keelung and return to Tonkin with the bulk of the Formosa expeditionary corps, leaving only a small French garrison at Makung in the Pescadores. In the second week of April Courbet and Duchesne drew up a plan for an opposed evacuation of Keelung, involving a carefully phased daylight withdrawal from the frontline forts to the harbour. A small rearguard would be left to hold the approaches to the harbour while the evacuation proceeded, supported by the guns of the Far East squadron. In the event this plan was never implemented, as preliminaries of peace between France and China were concluded on 4 April 1885, bringing the Sino-French War to an end. On 10 April Courbet was ordered to suspend plans for an immediate evacuation of Keelung, and on 14 April he was notified of the conclusion of preliminaries of peace ten days earlier. Hostilities around Keelung now came to an end.[49]

Japanese interest in the Keelung campaign

The French endeavours at Keelung were of great interest to another predatory power in the region, the Empire of Japan. In 1874 the Japanese had sent a punitive expedition to southern Taiwan, following the murder of shipwrecked Japanese sailors by Taiwanese aborigines, and Japanese expansionists already had their eye on Taiwan as a future Japanese colony. Following the failure of the Gapsin Coup in Korea in December 1884, Japan began to look ahead to an eventual showdown with China. Although France and Japan never became formal allies during the Sino-French War (despite Chinese fears of such a possibility), Japan's naval and military leaders observed the performance of Admiral Courbet's squadron and Colonel Duchesne's Formosa expeditionary corps with keen professional interest. The Japanese captain Tōgō Heihachirō, the future commander-in-chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy, visited Keelung during the war aboard the corvette Amagi and was briefed by French officers on the tactics the French were using against the Chinese. Togo's guide was the young French engineering captain Joseph Joffre, who had been sent to Keelung to lay out the new French forts after Duchesne's March victory. Commander-in-chief of the French Army at the start of the First World War and victor of the crucial Battle of the Marne in 1914, Joffre would end his military career as a Marshal of France.[50]

French evacuation of Keelung, June 1885

The Formosa expeditionary corps continued to occupy Keelung and Makung for several months after the end of the Sino-French War as a surety for the withdrawal of Chinese forces from Tonkin. During this period a battalion of marine infantry and a newly arrived marine artillery battery were withdrawn from the Keelung garrison to take part in a French punitive campaign in Madagascar.[51]

Keelung was finally evacuated on 22 June 1885. Under arrangements agreed between Liu Mingchuan and Admiral Lespès on 17 June, the French withdrew from their forts on Hung-tan-shan and Yueh-mei-shan in stages, over a three-day period, and their positions were reoccupied by the Chinese only after a prudent delay. The Chinese officers kept their men well in hand, and the occupation of the French forts was conducted with dignity and restraint. "There was not the slightest demonstration of triumph, nothing that could hurt our feelings, nothing that could wound our legitimate pride," wrote one French officer. The French flag that had flown above Keelung for eight months was lowered to a 21-gun salute from the ironclad La Galissonnière. Colonel Duchesne, the commander of the Formosa expeditionary corps, was the last French soldier to embark aboard the waiting transports. The men of the Formosa expeditionary corps were ferried either to Makung in the Pescadores, which would remain in French hands for another month, or to Along Bay in Tonkin, to rejoin the Tonkin expeditionary corps.[52]

By June 1885 Keelung was virtually unrecognisable as a Chinese town. Although its temples had been respected by the occupiers, many of its houses had been demolished to provide fields of fire for the French garrison, and the remaining buildings had been whitewashed and decorated in the French mode. The French had also built a network of broad avenues and boulevards through the town, and turned the waterfront into an esplanade, complete with bandstand.[53] The Canadian missionary George MacKay mentioned that Keelung was reoccupied by its former inhabitants as soon as the French warships steamed out of the harbour, but he did not comment on their reaction to the transformation that had taken place in their absence. Before long, however, Keelung was once again its former self.[54]

The French cemetery in Keelung

Only one trace remains today of the French occupation. At the request of Admiral Lespès, Liu Mingchuan undertook to respect the cemetery in which the French war dead had been buried.[55] This promise was kept, and the French cemetery in Keelung can still be seen today. The French dead, between 600 and 700 soldiers and sailors (most of them victims of cholera and typhoid rather than battle casualties),[56][57][58] were originally buried in a cemetery further to the north, close to the Erh-sha-wan battery, and their remains were transferred to the present cemetery in 1909.[59] The French cemetery contains only two named graves, those of sous-commissaire Marie-Joseph-Louis Dert and Lieutenant Louis Jehenne. Ironically, these two marine infantry officers died not in Keelung but in Makung in the Pescadores Islands, in June 1885, and their remains were exhumed and transferred to the Keelung cemetery in 1954.[60]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Chinese: t 蘇得勝, s 苏得胜, p Sū Déshèng, w Su Te-sheng.

- ↑ Ber’s battalion consisted of the 23rd, 26th, 27th and 28th Companies, 3rd Marine Infantry Regiment (Captains Casse, Marty, Carré and Melse). Lacroix’s battalion consisted of the 21st, 22nd, 23rd and 24th Companies, 2nd Marine Infantry Regiment (Captains Bauche, Thirion, Leverger and Onffroy de la Rozière). Lange’s battalion consisted of the 25th, 26th, 27th and 30th Companies, 2nd Marine Infantry Regiment (Captains Amouroux, Bertin, Cramoisy and Le Boulaire). The four companies of Lacroix’s battalion were taken from Tonkin, as were Bertin and Cramoisy’s companies of Lange's battalion, while the other six companies were drawn from the garrisons of Cochinchina. The infantry were supported by the 23rd Marine Artillery Battery (Captain de Champglen) and a section (2 guns) of the 11th Battery, 12th Army Artillery Regiment (Lieutenant Naud). The Hotchkiss detachment was under the command of lieutenant de vaisseau Barry.

- ↑ Chinese: 章高元, p Zhāng Gāoyuán, w Chang Kao-yuan.

- ↑ Chinese: 曹志忠, p Cáo Zhìzhōng, w Ts‘ao Chih-chung.

- ↑ Chinese: t 林朝棟, s 林朝栋, p Lín Cháodòng, w Lin Ch‘ao-tung.

- ↑ The 3rd African Battalion sent its 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th Companies to Formosa (Captains Pénasse, de Fradel, Michaud and Bernhart). The Legion company officers were Captains du Marais, Césari and Lebigot and Lieutenant Jannet.

- ↑ Chinese: t 張仁貴, s 张仁贵, p Zhāng Rénguì, w Chang Jen-kuei.

- ↑ Chinese: t 王詩正, s 王诗正, p Wáng Shīzhēng, w Wang Shih-cheng.

References

Citations

- ↑ ed. Piehler 2013, p. 1388.

- ↑ John King Fairbank (1978). The Cambridge History of China: Late Chʻing, 1800-1911, pt. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 251–. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3.

- ↑ Keeling 2011, p. 386.

- ↑ Loir, 89–91

- ↑ Lung Chang, 273–4

- ↑ Loir, 91–4

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 23–31; Loir 1886, pp. 94–101

- ↑ Billot, 244–52; Garnot 1894, pp. 35–7; Thomazi, 213

- ↑ Billot, 252–4; Garnot 1894, pp. 36–38; Thomazi, 213–14

- ↑ Loir, 183

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 41–5; Loir, 182–3

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 45–7; Loir, 184–8

- ↑ Davidson 1903, p. 227

- ↑ Tsai 2009, p. 97.

- ↑ Davidson 1903, pp. 223–4

- ↑ Davidson 1903, pp. 230–1.

- ↑ Davidson 1903, pp. 225–31

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 45–57; Lung Chang, 326

- ↑ Tsai 2009, pp. 98-99.

- ↑ Davidson 1903, p. 229

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 59–74; Poyen-Bellisle, 26–34

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 83–7

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 87–9, 93–5; Poyen-Bellisle, 35–41; Rouil, 60–65

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 74–8

- ↑ Davidson 1903, pp. 232–3

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 78–82; Loir, 209–44

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 138–40

- ↑ Rouil, 60–61

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 107–14; Poyen-Bellisle, 54–6

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 119–35; Lung Chang, 327

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 135–44; Loir, 239–41; Rouil, 86–7

- ↑ Garnot 1894, p. 131

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 147–72; Lung Chang, 327; Poyen-Bellisle, 76–89

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 147–8; Poyen-Bellisle, 77–9

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 149–52; Poyen-Bellisle, 80–82

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 152–9; Poyen-Bellisle, 82–5

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 159–60; Poyen-Bellisle, 85–6

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 160–64; Poyen-Bellisle, 86–7

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 164–7; Poyen-Bellisle, 87

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 167–8; Poyen-Bellisle, 87

- ↑ Garnot 1894, p. 170; Poyen-Bellisle, 88–9

- ↑ Garnot, 168–9; Poyen-Bellisle, 88

- ↑ Garnot, 172

- ↑ Davidson 1903, p. 234

- ↑ Duboc, 295–303; Ferrero, 109–14; Garnot, 179–95; Loir, 291–317

- ↑ Lung Chang, 327

- ↑ Garnot, 172–7; Poyen-Bellisle, 89–100

- ↑ Garnot, 175; Poyen-Bellisle, 100–103

- ↑ Garnot, 195–206

- ↑ Busch, 38; Falk, 123

- ↑ Garnot, 208–12

- ↑ Garnot, 225–30; Poyen-Bellisle, 107–11

- ↑ Loir, 239–41; Rollet de l'Isle, 293–300

- ↑ MacKay, 199–201

- ↑ Garnot, 230

- ↑ 120 on the battlefield, 150 from their wounds, the others because of diseases. Joeck, 8.

- ↑ Crook, Steven (Nov 15, 2001). "Exhuming French history in Taiwan". Taipei Times. p. 11.

- ↑ Tsai 2009, p. 103.

- ↑ The 1630 m² cemetery is located at Tchong Pan teou, Tchong Tcheng district, Keelung. Joeck, 8.

- ↑ Rouil, 149–68

Bibliography

- Billot, A., L’affaire du Tonkin: histoire diplomatique du l’établissement de notre protectorat sur l’Annam et de notre conflit avec la Chine, 1882–1885, par un diplomate (Paris, 1888)

- Busch, N. F., The Emperor's Sword: Japan versus Russia in the Battle of Tsushima (1969)

- Davidson, James W. (1903). "Chapter XVI: The French Campaign in Formosa. 1884-1885". The Island of Formosa, Past and Present : history, people, resources, and commercial prospects : tea, camphor, sugar, gold, coal, sulphur, economical plants, and other productions. London and New York: Macmillan & co. pp. 219–242. OL 6931635M.

- Davidson, James Wheeler, The Island of Formosa: Historical View from 1430 to 1900 (London, 1903)

- Duboc, E., Trente cinq mois de campagne en Chine, au Tonkin (Paris, 1899)

- Falk, E. A., Togo and the Rise of Japanese Sea Power (New York, 1936)

- Ferrero, Stéphane, Formose, vue par un marin français du XIXe siècle (Paris, 2005)

- Garnot, Eugène Germain (1894). L' expédition française de Formose, 1884-1885. Paris: Librairie C. Delagrave. OCLC 3986575. OL 5225244M.

- Joeck, Claude R. Le cimetière Français de Keelung et le monument à la mémoire de l'amiral Courbet de Makung (Taiwan) LSF, Le Souvenir Français, N°25, déc. 2008, pp. 7–8.

- Loir, M., L'escadre de l'amiral Courbet (Paris, 1886)

- Lung Chang [龍章], Yueh-nan yu Chung-fa chan-cheng [越南與中法戰爭, Vietnam and the Sino-French War] (Taipei, 1993)

- Mackay, George L. (1896). From Far Formosa. New York: F. H. Revell Co. OCLC 855518794.

- Poyen-Bellisle, H. de, L'artillerie de la Marine à Formose (Paris, 1888)

- Rollet de l'Isle, M., Au Tonkin et dans les mers de Chine (Paris, 1886)

- Rouil, C., Formose: des batailles presque oubliées (Taipei, 2001)

- Thirion, P., L'expédition de Formose (Paris, 1898)

- Thomazi, A., La conquête de l'Indochine (Paris, 1934)

- Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (2009). Maritime Taiwan: Historical Encounters with the East and the West (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765623285. Archived from the original on 13 July 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2014.