Kaw people

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,126[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Languages | |

| English, Kansa | |

| Religion | |

| Native American Church, Christianity, traditional tribal religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Siouan peoples |

The Kaw Nation (or Kanza, or Kansa) are a federally recognized Native American tribe in Oklahoma. They come from the central Midwestern United States. The tribe known as Kaw have also been known as the "People of the South wind",[2] "People of water", Kansa, Kaza, Kosa, and Kasa. Their tribal language is Kansa, classified as a Siouan language.[3]

The toponym "Kansas" was derived from the name of this tribe. The name of Topeka, capital city of Kansas, is said to be the Kaw word Tó Ppí Kˀé meaning "a good place to grow potatoes."[4] The Kaw are closely related to the Osage Nation, with whom members often intermarried.

Government

The Kaw Nation's headquarters is in Kaw City, Oklahoma, and the tribal jurisdictional area is within Kay County, Oklahoma. The elected chairwoman is Jacque Secondine Hensley currently serving a four-year term. Of the 3,126 enrolled members, 1,428 of them live within the state of Oklahoma.[1]

Economic development

Kaw Nation owns the Kanza Travel Plaza; Woodridge Market; Smoke Shop I, and II; SouthWind Casino; including a bingo hall, and an off-track wagering facility; and SouthWind Casino Braman, Which opened September 2014. The estimated annual economic impact of the tribe is $200 million.[1] The tribe also operates the Kanza Health Clinic, Kanza Wellness Center, Kaw Nation School Age Enrichment Center, Kanza Museum, Kaw Nation Environmental Department, Kaw Nation Police Department, Kaw Nation Social Service and Educational Department, Kaw Nation Emergency Management Department, Kaw Language Department and the Kaw Nation Judicial Branch. The Kaw Nation Judicial Branch includes a domestic violence program. The Kaw Nation operates its own Housing Authority, library, Title VI Food Services and issues its own tribal vehicle tags.[5] The Kanza News, the newsletter of Kaw Nation, is published quarterly.

History

Early history

The Kaw are a member of the Dhegiha branch of the Siouan language family. Oral history indicates that the ancestors of the five Dhegiha tribes migrated west from the Ohio Valley. The Quapaw separated from the other Dhegiha at the mouth of the Ohio, going down the Mississippi River to live in what is today the state of Arkansas. The other Dhegiha proceeded up the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. The Osage left the main group in central Missouri; the Kaw halted upstream on the Missouri River in northeastern Kansas; the Omaha and Ponca continued north to settle in Nebraska and South Dakota.[6]

This tradition is reinforced by the fact that the Illinois and Miami Indians called the lower Ohio and Wabash Rivers the Akansea River, because, as they told French explorers, the Akansea (Quapaw) formerly dwelt there.[7]

The Dhegiha probably migrated westward in the early to mid-17th century. Their reason for leaving their traditional home may have been due to the displacement westward of Indian tribes caused by European settlement on the Atlantic Coast of the United States. Displacement and Western migration was the fate of many Indian tribes. The first certain knowledge we have of the Dhegiha is 1673 when the French explorer of the Mississippi River, Pere Marquette, drew a crude map which showed the Dhegiha tribes near their historic locations.[8]

The French explorer Bourgmont was the first European known to visit the Kaws in 1724. He found them living in a single large village near the future site of the town of Doniphan, Kansas, on a bluff overlooking the Missouri River.[9] In 1780 the Kaw abandoned this village and took up residence on the Kansas River, but the ruins of their earlier village were long a landmark for travelers.[10] When Lewis and Clark ascended the Missouri, they noted passing the site of the “old village of the Kanzas” on July 2, 1804.[11]

Traditional culture and subsistence

From 1780 to 1830 the Kaw lived at Blue Earth Village on the Kansas River, at the site of present-day Manhattan, Kansas.[10] The Kaw probably moved to the Kansas River Valley to be closer to the buffalo herds on the Great Plains. The tribe increasingly depended upon buffalo hunting for its subsistence and less on agriculture. Also, living on the Kansas River gave them access to a rich territory of fur bearing animals to trade to the French for guns and other commodities. Unfortunately, this movement west also made them more vulnerable to attack from powerful enemies such as the Pawnees. Lewis and Clark noted that they were "reduced by war with their neighbors." They estimated the Kaw to number 300 men—about 1,500 persons in all.[12]

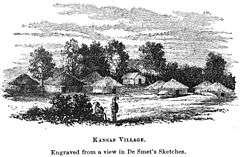

The traveler George C. Sibley gave a favorable description of the Kaw in 1811. He visited their village at the junction of the Big Blue River and Kansas Rivers. "The town contains 128 houses, or lodges, which are generally about sixty feet long and twenty-five feet wide...They are commodious and quite comfortable...." The Kaw "are governed by a chief and the influence of the oldest and most distinguished warriors. They are seldom at peace with any of their neighbors, except the Osage, with whom there appears to be a cordial and lasting relationship. The Kansas are a stout, hardy, handsome race, more active and enterprising even than the Osage. They are noted for their bravery and heroic daring."[13] The Kaw lived in their village about one-half the year. The women tended corn fields. The other half year they journeyed to western Kansas to hunt buffalo while living in teepees. Horse racing and hunting were said to be the two passions of the men. They were, in the words of Sibley, "homeless wanderers and such is the stubbornness of their Nature that they will rather remain as they are."[14] The Kaw would continue to be regarded as conservative and resistant to change.

Interaction with the United States

The purchase by the United States of Louisiana Territory in 1803 was to have a disastrous impact on the Kaw. They were increasingly hemmed in, first, by Eastern Indians forced to migrate west and, secondly, by White settlers who coveted the "beautiful aspects" and "rich and exuberant soils" of the land occupied and claimed by the Kaw.[15] West of the Kaw lived the warlike Cheyenne and Comanche, and to the north were the Pawnee, their traditional enemies. In 1825, the Kaw ceded a huge area of land in Missouri and Kansas to the United States in exchange for a promise of an annuity of $3,500 annually for twenty years. The promised annuity—to be paid in goods and services—was often late in arriving or found its way into the pockets of unscrupulous government officials and merchants. The Kaw were indifferent to the pleas of government agents and missionaries that they take up farming as their sole livelihood.

Meanwhile, the Kaw faced smallpox epidemics in 1827–1828 and 1831–1832, which killed about 500.[16] During the same period the tribe split into four different competing groups living in different villages, a consequence of rivalry between three groups of conservatives, who favored retaining traditional ways, and one group under White Plume which favored accommodation with the United States. Important in the latter group were 23 mixed bloods, the sons and daughters of French traders who had taken Kaw wives. The French influence among the Kaw is still seen today in common surnames such as Pappan, Bellmard, and Chouteau.

A disastrous flood in 1844 destroyed most of the land the Kaw had planted and left the tribe destitute. In 1846, the Kaw sold most of their remaining 2,000,000 acres (8,100 km2) of land for $202,000 plus a 256,000 acres (1,040 km2) reservation centered on Council Grove, Kansas.[17] Council Grove is a beautiful area of forests, water, and tall grass prairie, but it was probably the worst location that could have been selected for the already weakened and demoralized tribe. It was a favorite stopping place for the rough-hewn teamsters and traders and voracious merchants on the Santa Fe Trail. The first Kaw arriving there were beaten up by traders.[18] The flourishing whiskey trade in Council Grove also proved to be deleterious. Whites invaded Indian lands and sporadic efforts by soldiers to force them off the reservation were ineffective. In 1860, the Kaw reservation, overrun by White settlers, was reduced to 80,000 acres (320 km2).

With the coming of the American Civil War in 1861, the Kaw and other Indians in Kansas suddenly became an asset as the state recruited them as soldiers and scouts to stave off invasions by slave-holding tribes and Confederate supporters in Indian Territory. Seventy young Kaw men were persuaded—or forced—to join Company L, Ninth Kansas Cavalry. They served in Indian Territory (Oklahoma) and Arkansas during the war and 21 of them never came home—a large loss to the already diminished numbers of the tribe.[19]

After the war, European-Americans in Kansas agitated for removal of Indians, including the Kaw. However, amidst the gloom of a tribe that seemed likely to disintegrate came one colorful moment. The Kaw and the Cheyenne had long been enemies. On June 1, 1868, about one hundred Cheyenne warriors descended on the Kaw reservation. Terrified white settlers took refuge in Council Grove. The Kaw men painted their faces, donned their finery, and sallied forth on horseback to meet the Cheyenne. The two Indian armies put on a military pageant featuring horsemanship, fearsome howls and curses, and volleys of bullets and arrows. After four hours, the Cheyenne retired with a few stolen horses and a peace offering of coffee and sugar by the Council Grove merchants. Nobody was hurt on either side.

During the battle, the mixed-blood Kaw interpreter, Joseph James, Jr. (more commonly known as Jojim or Joe Jim) galloped 60 miles to Topeka to request assistance from the Governor. Riding along with Jojim was an eight-year-old, part-Indian boy named Charles Curtis or “Indian Charley.” Curtis would later become a jockey, a lawyer, a politician, and Vice President of the United States under Herbert Hoover.[20]

White pressure finally forced the Kaw out of Kansas. On June 4, 1873, they packed up their meager possessions in wagons and headed south to Indian Territory to a new reservation. Two weeks later, 533 men, women, and children arrived at the junction of the Arkansas River and Beaver Creek in what would become Kay County, Oklahoma.[21] The Kaw made their last successful buffalo hunt that winter, journeying on horseback to the Great Salt Plains. They preserved the buffalo meat by jerking it and sold the buffalo robes for five thousand dollars.[22]

The Kaw continued their decline in Oklahoma. In 1879, their agent reported that nearly half of their number had died of contagious diseases in the previous seven years. In the 1880s and 1890s, the Kaw derived much of their income from leasing their land to White ranchers for grazing. In 1884, to manage grazing leases, they elected a government with a Chief Councilor and a representative from each of the four Kaw bands: the Picayune, Koholo, Rock Creek, and Half-breed. Washungah was elected as the Chief Councilor in 1885 and the tribal headquarters was later named Washunga to honor him.[23]

20th century

The Kaws found security from White harassment on their Indian Territory lands, but the tribe continued to decline, especially the full bloods. By 1888 they numbered only 188 persons and the Kaws seemed on the road to extinction.[24] However, they slowly acculturated and their numbers increased, mostly through intermarriage as the number of full-bloods continued to decline. By 1910, only one old woman in the tribe could not speak English and more than 80 percent were literate.[25]

The Curtis act of 1898 expanded the powers of the federal government over Indian affairs. The author of the act was Charles Curtis, now a Congressman. Curtis believed that the Indians should be assimilated and he supported the break-up of tribal governments and the allotment of tribal lands to their members. In 1902, at Curtis’s urging, Congress abolished the Kaw tribal government and reservation and divided tribal lands among members. Each of 247 Kaw tribal members received 405 acres (1.6 km2), of which 160 acres (0.6 km2) were for a personal homestead. Curtis and his son and two daughters thus received 1,620 acres (6.6 km2) of land.[26] Most Kaws sold or lost their land. By 1945, only 13 percent of the land of the former Kaw Reservation was owned by Kaws.[27] Much former Kaw land was inundated by the creation of Kaw Lake in the 1960s, including their Council House and cemetery at Washunga which was moved to Newkirk, Oklahoma.

After the death of Washunga in 1908, the Kaw people had no formal organization for many years. In 1922, Washunga's adopted daughter Lucy Tayiah Eads (Little Deer) was elected principal chief along with a council of eight members, and was the first and only female chief, but in 1928 the government agency to the Kaw was abolished and the buildings sold.[28] Thereafter, the Kaw had no recognized government until federal recognition and reorganization of the tribe in 1959. In 1990, the Kaw ratified a new tribal constitution and created a tribal court in 1992. In 2000, the tribe purchased lands on their pre-1873 reservation near Council Grove, Kansas to create a park commemorating their history in Kansas named the Allegawaho Memorial Heritage Park.

The last fluent speaker of the Kansa language, Walter Kekahbah died in 1983.[29] {As of 2012, the Kaw Nation offers online language learning for Kansa second language speakers}.[30]

The last full-blood Kaw, William Mehojah died in 2000.[31]

Notable Kaw people

- Allegawaho, b. ca. 1820, d. ca. 1897, Kaw Chief, 1867-1873. Allegawaho Heritage Memorial Park in Council Grove, Kansas is named after him.

- Charles Curtis, the only Native American to be elected Vice President of the United States (under Herbert Hoover (1929–1933)). More important was his Congressional career, where he served long terms both in the House and Senate, where he was elected Minority Whip and Majority Leader, reflecting his ability to manage legislation and build deals. Curtis' mother Ellen Pappan Curtis was one-quarter each of Kaw, Osage, Potawatomi and French ancestry.[32]

- Lucy Tayiah Eads, b. 1888, adopted daughter of Washunga. Elected Chief of Kaw in 1920s and attempted to get federal recognition for the tribe.

- Joseph James and Joseph James, Jr. (Joe Jim or Jojim) 19th century interpreters and guides.

- William A. Mehojah, the last Kaw full blood, died on April 23, 2000. The Allegawaho Memorial Heritage Park (AMHP) was dedicated in his name on June 19, 2005 near Council Grove, Kansas.

- Jim Pepper, the U.S. jazz saxophonist, singer, and composer was of both Kaw and Creek ancestry

- Maude McCauley Rowe, died in 1978. One of the last three native speakers of the Kansa language. Between 1974 and 1977 linguist Robert Rankin recorded many hours of Rowe speaking Kansa, thus enabling the survival of the language and many of its oral traditions.[33]

- Washunga, principal chief of the Kaws from 1873 until his death in 1908. Washunga, Oklahoma was named for him.

- White Plume. Monchousia, Kaw Chief who visited President Monroe in 1822 in Washington D.C.

- Mark Branch, two-time NCAA-champion wrestler and University of Wyoming wrestling coach (2008–Present). Branch won NCAA championships in the 167-pound weight class in 1994 and 1997 and placed second in 1995 and 1996. Branch won four straight Western Wrestling Conference titles as the coach of Wyoming. He has been named WWC Coach of the Year three times.[34]

- Chris Pappan, ledger artist.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 2011 Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Directory. Archived 2012-05-12 at the Wayback Machine. Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. 2011: 17. Retrieved 4 Jan 2012.

- ↑ "Constitution of the Kaw Nation." Kaw Nation. 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ Unrau, William. Kaw (Kansa). Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. Retrieved 21 Feb 2009.

- ↑ Connelley, William E. "Origin of the Name of Topeka" Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, Vol 27, 589-593.

- ↑ Kanza Cultural History. The Kaw Nation. (retrieved 29 April 2012)

- ↑ Unrau,William E. Kansa Indians: A History of the Wind People, 1673–1873, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971: 12-14.

- ↑ Accessed, Feb 21, 2010

- ↑ Dorsey, James Owen, "Migration of the Siouan Tribes," The American Naturalist, Vol XX, Mar 1886, 214.

- ↑ Norall,Frank. Bourgmont, Explorer of the Missouri, 1698-1725. Lincoln: University of Neb Press, 1988, 51

- 1 2 Olson, Kevin (2012). Frontier Manhattan. University Press of Kansas. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-7006-1832-3.

- ↑ , Accessed, Feb 23, 2010

- ↑ Accessed, Feb 23, 2010

- ↑ Lutting, John C. Journal of a Fur-Trading Expedition on he Upper Missouri, 1812-1813.. St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society, 1920,36-37.

- ↑ Unrau, Kansa Indins, 106

- ↑ Unrau, Kansa Indians, 105

- ↑ Unrau, Kansa Indians, 149-150

- ↑ Unrau, ibid, 159-161

- ↑ Unrau, Kansa Indians 163

- ↑ National Archives, Record Group M-234, Tape 467,page 476

- ↑ Unrau, William E. Mixed Bloods and Tribal Dissolution: Charles Curtis and the Quest for Indian Identity, Norman: University of Okla Press, 1971: 72-75.

- ↑ Unrau, Mixed Bloods, 92

- ↑ Accessed, Aug 12, 1999.

- ↑ Finney, Frank F. "The Kaw Indians and their Indian Territory Agency." Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vol. 35, 1957-58, p. 418

- ↑ Accessed, Feb 22, 2010.

- ↑ Accessed Feb 22,2010. Reddy, Marlita A., ed. Statistical Record of Native North Americans, Detroit: Gale Research, 166, 189

- ↑ Finney,Frank F. "The Kay Indians and their Indian Territory Agency." Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vp; 35. No. 4, 1957, 416-422

- ↑ Chapman, Berlin B. "Charles Curtis and the Kaw Reservation." Kansas Historical Quarterly.Vol XV, No. 4. Nov 1947, p. 351

- ↑ Finney, p. 423

- ↑ Ranney, Dave. "Researchers try to preserve Indian languages." accessed 8 Apr 2011

- ↑ [Ranney, Dave. “Researchers try to preserve Indian languages.”, accessed 12 Apr 2011]

- ↑ OK/IT GenWeb. "The Kansas/Kanza/Kaw Nation." Accessed 30 Nov 2011

- ↑ Charles Curtis, U.S. Senate: Art & History, US Senate.gov, reprinted from Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789-1993, Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1997, accessed 10 Aug 208

- ↑ Ranney, Dave. "Researchers try to preserve Indian Languages." http://www2.ljworld.com/news/2005/aug/01/researchers_try_preserve_indian_languages/, accessed 8 Apr 2011

- ↑ http://www.gowyo.com/sports/m-wrestl/mtt/branch_mark00.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kaw tribe. |

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about Kaw people. |

- Kaw Nation, official website

- Al-le-ga-wa-ho Memorial

- Rootsweb Kaw article.

- WebKanza: The Online Home of the Kanza Language