Kater's pendulum

A Kater's pendulum is a reversible freeswinging pendulum invented by British physicist and army captain Henry Kater in 1817[1] for use as a gravimeter instrument to measure the local acceleration of gravity. Its advantage is that, unlike previous pendulum gravimeters, the pendulum's centre of gravity and center of oscillation do not have to be determined, allowing greater accuracy. For about a century, until the 1930s, Kater's pendulum and its various refinements remained the standard method for measuring the strength of the Earth's gravity during geodetic surveys. It is now used only for demonstrating pendulum principles.

Description

A pendulum can be used to measure the acceleration of gravity g because for narrow swings its period of swing T depends only on g and its length L:[2]

So by measuring the length L and period T of a pendulum, g can be calculated.

The Kater pendulum consists of a rigid metal bar with two pivot points, one near each end of the bar. It can be suspended from either pivot and swung. It also has either an adjustable weight that can be moved up and down the bar, or one adjustable pivot, to adjust the periods of swing. In use, it is swung from one pivot, and the period timed, and then turned upside down and swung from the other pivot, and the period timed. The movable weight (or pivot) is adjusted until the two periods are equal. At this point the period T is equal to the period of an 'ideal' simple pendulum of length equal to the distance between the pivots. From the period and the measured distance L between the pivots, the acceleration of gravity can be calculated with great precision from the equation (1) above.

History

Gravity measurement with pendulums

The first person to discover that gravity varied over the Earth's surface was French scientist Jean Richer, who in 1671 was sent on an expedition to Cayenne, French Guiana, by the French Académie des Sciences, assigned the task of making measurements with a pendulum clock. Through the observations he made in the following year, Richer determined that the clock was 2½ minutes per day slower than at Paris, or equivalently the length of a pendulum with a swing of one second there was 1¼ Paris lines, or 2.6 mm, shorter than at Paris.[3][4] It was realized by the scientists of the day, and proven by Isaac Newton in 1687, that this was due to the fact that the Earth was not a perfect sphere but slightly oblate; it was thicker at the equator because of the Earth's rotation. Since the surface was farther from the Earth's center at Cayenne than at Paris, and also the centrifugal contribution from the Earth's rotation was stronger, and in spite of the presence of more mass underneath, the net effect was that gravity was weaker there. Since that time pendulums began to be used as precision gravimeters, taken on voyages to different parts of the world to measure the local gravitational acceleration. The accumulation of geographical gravity data resulted in more and more accurate models of the overall shape of the Earth.

Pendulums were so universally used to measure gravity that, in Kater's time, the local strength of gravity was usually expressed not by the value of the acceleration g now used, but by the length at that location of the seconds pendulum, a pendulum with a period of two seconds, so each swing takes one second. It can be seen from equation (1) that for a seconds pendulum, the length is simply proportional to g:

Inaccuracy of gravimeter pendulums

In Kater's time, the period T of pendulums could be measured very precisely by timing them with precision clocks set by the passage of stars overhead. Prior to Kater's discovery, the accuracy of g measurements was limited by the difficulty of measuring the other factor L, the length of the pendulum, accurately. L in equation (1) above was the length of an ideal mathematical 'simple pendulum' consisting of a point mass swinging on the end of a massless cord. However the 'length' of a real pendulum, a swinging rigid body, known in mechanics as a compound pendulum, is more difficult to define. In 1673 Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens in his mathematical analysis of pendulums, Horologium Oscillatorium, showed that a real pendulum had the same period as a simple pendulum with a length equal to the distance between the pivot point and a point called the center of oscillation, which is located under the pendulum's center of gravity and depends on the mass distribution along the length of the pendulum. The problem was there was no way to find the location of the center of oscillation in a real pendulum accurately. It could theoretically be calculated from the shape of the pendulum if the metal parts had uniform density, but the metallurgical quality and mathematical abilities of the time didn't allow the calculation to be made accurately.

To get around this problem, most early gravity researchers, such as Jean Picard (1669), Charles Marie de la Condamine (1735), and Jean-Charles de Borda (1792) approximated a simple pendulum by using a metal sphere suspended by a light wire. If the wire had negligible mass, the center of oscillation was close to the center of gravity of the sphere. But even finding the center of gravity of the sphere accurately was difficult. In addition, this type of pendulum inherently wasn't very accurate. The sphere and wire didn't swing back and forth as a rigid unit, because the sphere acquired a slight angular momentum during each swing. Also the wire stretched elastically during the pendulum's swing, changing L slightly during the cycle.

Kater's solution

However, in Horologium Oscillatorium, Huygens had also proved that the pivot point and the center of oscillation were interchangeable. That is, if any pendulum is suspended upside down from its center of oscillation, it has the same period of swing, and the new center of oscillation is the old pivot point. The distance between these two conjugate points was equal to the length of a simple pendulum with the same period.

As part of a committee appointed by the Royal Society in 1816 to reform British measures, Kater had been contracted by the House of Commons to determine accurately the length of the seconds pendulum in London.[5] He realized Huygens' principle could be used to find the center of oscillation, and so the length L, of a rigid (compound) pendulum. If a pendulum were hung upside down from a second pivot point that could be adjusted up and down on the pendulum's rod, and the second pivot were adjusted until the pendulum had the same period as it did when swinging right side up from the first pivot, the second pivot would be at the center of oscillation, and the distance between the two pivot points would be L.

Kater wasn't the first to have this idea.[6][7] French mathematician Gaspard de Prony first proposed a reversible pendulum in 1800, but his work was not published till 1889. In 1811 Friedrich Bohnenberger again discovered it, but Kater independently invented it and was first to put it in practice.

(a) opposing knife edge pivots from which pendulum is suspended

(b) fine adjustment weight moved by adjusting screw

(c) coarse adjustment weight clamped to rod by setscrew

(d) bob

(e) pointers for reading

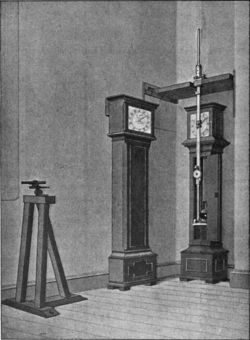

The pendulum

Kater built a pendulum consisting of a brass rod about 2 meters long, 1½ inches wide and one-eighth inch thick, with a weight (d) on one end.[1][8] For a low friction pivot he used a pair of short triangular 'knife' blades attached to the rod. In use the pendulum was hung from a bracket on the wall, supported by the edges of the knife blades resting on flat agate plates. The pendulum had two of these knife blade pivots (a), facing one another, about a meter (40 in) apart, so that a swing of the pendulum took approximately one second when hung from each pivot.

Kater found that making one of the pivots adjustable caused inaccuracies, making it hard to keep the axis of both pivots precisely parallel. Instead he permanently attached the knife blades to the rod, and adjusted the periods of the pendulum by a small movable weight (b,c) on the pendulum shaft. Since gravity only varies by a maximum of 0.5% over the Earth, and in most locations much less than that, the weight only had to be adjusted slightly. Moving the weight toward one of the pivots decreased the period when hung from that pivot, and increased the period when hung from the other pivot. This also had the advantage that the precision measurement of the separation between the pivots only had to be made once.

Experimental procedure

To use, the pendulum was hung from a bracket on a wall, with the knife blade pivots supported on two small horizontal agate plates, in front of a precision pendulum clock to time the period. It was swung first from one pivot, and the oscillations timed, then turned upside down and swung from the other pivot, and the oscillations timed again. The small weight (c) was adjusted with the adjusting screw, and the process repeated until the pendulum had the same period when swung from each pivot. By putting the measured period T, and the measured distance between the pivot blades L, into the period equation (1), g could be calculated very accurately.

Kater performed 12 trials.[1] He measured the period of his pendulum very accurately using the clock pendulum by the method of coincidences; timing the interval between the coincidences when the two pendulums were swinging in synchronism. He measured the distance between the pivot blades with a microscope comparator, to an accuracy of 10−4 in. (2.5 μm). As with other pendulum gravity measurements, he had to apply small corrections to the result for a number of variable factors:

- the finite width of the pendulum's swing, which increased the period

- temperature, which caused the length of the rod to vary due to thermal expansion

- atmospheric pressure, which reduced the effective mass of the pendulum by the buoyancy of the displaced air, increasing the period

- altitude, which reduced the gravitational force with distance from the center of the Earth. Gravity measurements are always referenced to sea level.

He gave his result as the length of the seconds pendulum. After corrections, he found that the mean length of the solar seconds pendulum at London, at sea level, at 62 °F (17 °C), swinging in vacuum, was 39.1386 inches. This is equivalent to a gravitational acceleration of 9.81158 m/s2. The largest variation of his results from the mean was 0.00028 inches (7.1 µm). This represented a precision of gravity measurement of 7(10−6) (7 milligals).

In 1824, the British Parliament made Kater's measurement of the seconds pendulum the official standard of length for defining the yard.

Use

The large increase in gravity measurement accuracy made possible by Kater's pendulum established gravimetry as a regular part of geodesy. To be useful, it was necessary to find the exact location (latitude and longitude) of the 'station' where a gravity measurement was taken, so pendulum measurements became part of surveying. Kater's pendulums were taken on the great historic geodetic surveys of much of the world that were being done during the 19th century. In particular, Kater's pendulums were used in the Great Trigonometric Survey of India.

Reversible pendulums remained the standard method used for absolute gravity measurements until they were superseded by free-fall gravimeters in the 1950s.[9]

Repsold–Bessel pendulum

Repeatedly timing each period of a Kater pendulum, and adjusting the weights until they were equal, was time consuming and error-prone. Friedrich Bessel showed in 1826 that this was unnecessary. As long as the periods measured from each pivot, T1 and T2, are close in value, the period T of the equivalent simple pendulum can be calculated from them:[10]

Here and are the distances of the two pivots from the pendulum's center of gravity. The distance between the pivots, , can be measured with great accuracy. and , and thus their difference , cannot be measured with comparable accuracy. They are found by balancing the pendulum on a knife edge to find its center of gravity, and measuring the distances of each of the pivots from the center of gravity. However, because is so much smaller than , the second term on the right in the above equation is small compared to the first, so doesn't have to be determined with high accuracy, and the balancing procedure described above is sufficient to give accurate results.

Therefore, the pendulum doesn't have to be adjustable at all, it can simply be a rod with two pivots. As long as each pivot is close to the center of oscillation of the other, so the two periods are close, the period T of the equivalent simple pendulum can be calculated with equation (2), and the gravity can be calculated from T and L with (1).

In addition, Bessel showed that if the pendulum was made with a symmetrical shape, but internally weighted on one end, the error caused by effects of air resistance would cancel out. Also, another error caused by the finite diameter of the pivot knife edges could be made to cancel out by interchanging the knife edges.

Bessel didn't construct such a pendulum, but in 1864 Adolf Repsold, under contract to the Swiss Geodetic Commission, developed a symmetric pendulum 56 cm long with interchangeable pivot blades, with a period of about ¾ second. The Repsold pendulum was used extensively by the Swiss and Russian Geodetic agencies, and in the Survey of India. Other widely used pendulums of this design were made by Charles Peirce and C. Defforges.

References

- 1 2 3 Kater, Henry (1818). "An account of experiments for determining the length of the pendulum vibrating seconds in the latitude of London". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. London. 104 (33): 109. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ↑ Nave, C. R. (2005). "Simple Pendulum". Hyperphysics. Dept. of Physics and Astronomy, Georgia State Univ. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- ↑ Poynting, John Henry; Joseph John Thompson (1907). A Textbook of Physics, 4th Ed. London: Charles Griffin & Co. p. 20.

- ↑ Victor F., Lenzen; Robert P. Multauf (1964). "Paper 44: Development of gravity pendulums in the 19th century". United States National Museum Bulletin 240: Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology reprinted in Bulletin of the Smithsonian Institution. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 307. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- ↑ Zupko, Ronald Edward (1990). Revolution in Measurement: Western European Weights and Measures since the Age of Science. New York: Diane Publishing. pp. 107–110. ISBN 0-87169-186-8.

- ↑ Lenzen & Multauf 1964, p. 315

- ↑ Poynting & Thompson 1907, p. 12

- ↑ Elias Loomis (1864). Elements of Natural Philosophy, 4th Ed. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 109.

- ↑ Torge, Wolfgang (2001). Geodesy: An Introduction. Walter de Gruyter. p. 177. ISBN 3-11-017072-8.

- ↑ Poynting & Thompson 1907, p. 15

External links

- The Accurate Measurement of g using Kater's pendulum, U. of Sheffield Has derivation of equations

- Kater, Henry (June 1818) An Account of the Experiments for determining the length of the pendulum vibrating seconds in the latitude of London, The Edinburgh Review, Vol. 30, p.407 Has detailed account of experiment, description of pendulum, value determined, interest of French scientists