Kingdom of Qocho

| Kara-Khoja Kingdom | ||||||||||||

| Kingdom | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Capital | Gaochang, Beshbalik | |||||||||||

| Languages | Tocharian, Indo-Iranian and later Old Uyghur language | |||||||||||

| Religion | Church of the East ("Nestorianism"), Manichaeism,[1][2] Buddhism[3] | |||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||

| • | Established | 843 | ||||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 1209/late 13th to mid 14th century | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Xinjiang |

|

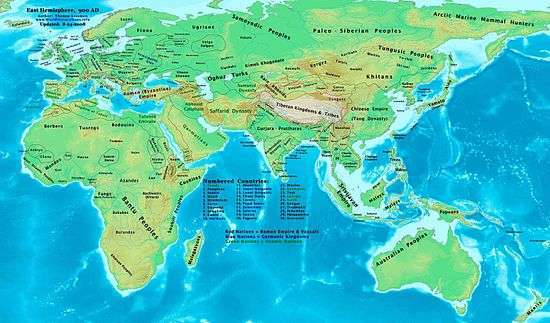

The Kingdom of Qocho, (Chinese: 高昌回鶻; pinyin: Gāochāng Húihú; literally: "Qocho Uyghurs", Mongolian ᠦᠶᠭᠦᠷ Uihur "id.") also called the Idiqut state[7][8][9][10] ("Holy Wealth, Glory"), was a Tocharian-Uyghur state created in 843 by Uyghur refugees fleeing from the destruction of the Uyghur Khaganate after having been driven out by the Yenisei Kirghiz. They made their summer capital in Qocho (modern Gaochang, also called Qara-Khoja, near modern Turpan) and winter capital in Beshbalik (modern Jimsar County, also previously known as Ting Prefecture).[11] Its population is referred to as the "Xizhou Uyghurs" after the old Tang Chinese name for Gaochang, the Qocho Uyghurs after their capital, the Kucha Uyghurs after another city they controlled, or the Arslan (lion) Uyghurs after their king's title.

The Kingdom of Qocho's rulers trace their lineage to Qutlugh of the Ediz dynasty of the Uyghur Khaganate.

History

In 843 a group of Uyghurs migrated southward under the leadership of Pangtele and occupied Karasahr and Kucha.

In 866 the Kingdom of Qocho captured Ting (Beshbalik) and Xi (Gaochang) prefectures as well as Luntai (Ürümqi) from the Guiyi Circuit.

In 869 the Kingdom of Qocho attacked the Guiyi Circuit but was repelled.

In 870 the Kingdom of Qocho attacked the Guiyi Circuit but was repelled.

In 876 the Kingdom of Qocho seized Yi Prefecture from the Guiyi Circuit, after which it came to be called Kumul.

By 887 they were settled under an agrarian lifestyle in the region of Qocho.

In 954 Ilig Bilgä Tengri rose to power.

In 981 Arslan Bilgä Tengri ilig rose to power.

In 984 Arslan Bilgä Tengri ilig became Süngülüg Khagan. In the same year a Song dynasty envoy reached Qocho and gave an account of the city:

There is no rain or snow here and it is extremely hot. Each year at the hottest time, the inhabitants dig holes in the ground to live in .... The earth here produces all the five grains except buckwheat. The nobility eat horseflesh, while the rest eat mutton, wild ducks and geese. Their music is largely played on the pipa and harp. They produce sables, fine white cotton cloth, and an embroidered cloth made from flower stamens. By custom they enjoy horseback riding and archery .... They use the [Tang] calendar produced in the seventh year of the Kaiyuan reign (719) ....They fashion pipes of silver or brass and channel flowing water to shoot at each other; or they sprinkle water on each other as a game, which they call pressing out the sun's heat to chase off sickness. They like to take walks, and the strollers always carry a musical instrument with them. There are over fifty Buddhist temples here, the names inscribed over their gates all presented by the Tang court. The temples house copies of the Buddhist scriptures (da zang jing) and the dictionaries Tang yun, Yupian and Jingyun. On spring nights the locals pass the time milling about between the temples.There's an "Imperial Writings Tower' which houses edicts written by the Tang emperor Taizong kept carefully secured. There's also a Manichaean temple, with Persian monks who keep their own religious law and call the Buddhist scriptures the 'foreign Way' .... In this land there are no poor people; anyone short of food is given public aid. People live to an advanced age, generally over one hundred years. No one dies young.[12]

In 996 Bügü Bilgä Tengri ilig succeeded Süngülüg Khagan.

In 1007 Alp Arsla Qutlugh Kül Bilgä Tengri Khan succeeded Bügü Bilgä Tengri ilig.

In 1024 Kül Bilgä Tengri Khan succeeded Alp Arsla Qutlugh Kül Bilgä Tengri Khan.

In 1068 Tengri Bügü il Bilgä Arslan Tengri Uighur Tärkän succeeded Kül Bilgä Tengri Khan.

In 1123 Bilgä rose to power. He was succeeded by Yur Temur at some point, who was succeeded by Barčuq Art iduq-qut.

In 1130 the Kingdom of Qocho became a vassal of the Qara Khitai.

In 1209 the Kingdom of Qocho became a vassal of the Mongol Empire.

In 1242 Kesmez iduq-qut succeeded Barčuq Art iduq-qut.

In 1246 Salïndï Tigin iduq-qut succeeded Kesmez iduq-qut.

In 1253 Ögrünch Tigin iduq-qut succeeded Salïndï Tigin iduq-qut.

In 1257 Mamuraq Tigin iduq-qut succeeded Ögrünch Tigin iduq-qut.

In 1266 Qosqar Tigin iduq-qut succeeded Mamuraq Tigin iduq-qut.

In 1280 Negüril Tigin iduq-qut succeeded Qosqar Tigin iduq-qut.

In 1318 Negüril Tigin iduq-qut died. The Kingdom of Qocho became part of the Chagatai Khanate.

In 1322 Tämir Buqa iduq-qut rose to power.

In 1330 Senggi iduq-qut succeeded Tämir Buqa iduq-qut.

In 1332 Taipindu iduq-qut succeeded Senggi iduq-qut.

In 1352 Ching Timür iduq-qut succeeded Taipindu iduq-qut and was the last known ruler governor of the kingdom.

By the 1370s the Kingdom of Qocho ceased to exist.

Culture

Mainly Turkic and Tocharian, but also Chinese and Iranian peoples such as the Sogdians were assimilated into the Uyghur Kingdom of Qocho.[13] Chinese were among the population of Qocho.[14] Peter B. Golden writes that the Uyghurs not only adopted the writing system and religious faiths of the Sogdians, such as Manichaeism, Buddhism, and Christianity, but also looked to the Sogdians as "mentors" while gradually replacing them in their roles as Silk Road traders and purveyors of culture.[15]

The Tang rule over Qocho and Turfan and Buddhism left a lasting legacy upon the Kingdom of Qocho with the Tang presented names remaining on the more than 50 Buddhist temples with Emperor Taizong of Tang's edicts stored in the "Imperial Writings Tower " and Chinese dictionaries like Jingyun, Yuian, Tang yun, and da zang jing (Buddhist scriptures) stored inside the Buddhist temples and Persian monks also maintained a Manichaean temple in the Kingdom, the Persian Hudud al-'Alam uses the name "Chinese town" to call Qocho, the capital city.[16]

The Uyghurs of Qocho continued to produce the Chinese Qieyun rime dictionary and developed their own pronunciations of Chinese characters, left over from the Tang influence over the area.[17]

The modern Uyghur linguist Abdurishid Yakup pointed out that the Turfan Uyghur Buddhists studied the Chinese language and used Chinese books like the Thousand Character Classic and Qieyun and it was written that "In Qocho city were more than fifty monasteries, all titles of which are granted by the emperors of the Tang dynasty, which keep many Buddhist texts as the Tripiṭaka, Tangyun, Yupuan, Jingyin etc."[18]

In Central Asia the Uyghurs viewed the Chinese script as "very prestigious" so when they developed the Old Uyghur alphabet, based on the Syriac script, they deliberately switched it to vertical like Chinese writing from its original horizontal position in Syriac.[19]

Race and ethnicity

Professor James A. Millward described the original Uyghurs as physically "Mongoloid" (an archaic term meaning "appearing ethnically Eastern or Inner Asian"), giving as an example the images of Uyghur patrons of Buddhism in Bezeklik, temple 9, until they began to mix with the Tarim Basin's original eastern Iranian inhabitants.[20] Buddhist Uyghurs created the Bezeklik murals.[21]

Conflict with the Kara-Khanid Khanate

Besides the jihad against Yutian (Kingdom of Khotan), the Uygur Karakhoja Kingdom (Kingdom of Qocho) was also subjected to Jihad in which Buddhist temples were razed and Islam spread by the Karakhanid ruler Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan.[22]

The '"Compendium of the Turkic Dialects" by Kashgari, included among the infidels, the Uyghurs.[23] It was written "just as the thorn should be cut at its root, so the Uighur should be struck on the eye" by Kashgari, who viewed them as untrustworthy and noted that Muslim Turks used the derogatory name "Tat" against the Buddhist Uyghurs whom Kashgari described as "infidels".[24] The identities of "Buddhist" and "Uyghur" were intertwined with each other.[25]

The Buddhist Uyghurs were subjected to an attack by the Muslim Turks and this was described in Mahmud Kashgari's work.[26] Mahmud Kaşgari's works contained poetry stanzas and verses which described fighting between Buddhist Uighurs (Buddhist Turks) and Muslim Karakahnids (Muslim Turks).[27] Uyghur Buddhist temples were desecrated and Uyghur cities were raided and Minglaq province across the river Ili was the target of the conquest against the Buddhist Uyghur by the Muslim Karakhanids as described in 5-6 stanzas of Kashgari's work.[28][29][30]

Mahmud Kashgari's "Three Turkic Verse Cycles" recorded in order - in the Irtysh Valley, a defeat inflicted on "infidel tribes" at the hands of the Karakhanids, secondly, the Buddhist Uyghurs being attacked by the Muslim Turks, and finally, a defeat inflicted upon "a city between Tangut and China.", Qatun Sini, at the hands of the Tangut Khan.[31][32]

Mahmud Kashgari insulted the Uyghur Buddhists as "Uighur dogs" and called them "Tats", which referred to the "Uighur infidels" according to the Tuxsi and Taghma, while other Turks called Persians "tat".[33][34] While Kashgari displayed a different attitude towards the Turks diviners beliefs and "national customs", he expressed towards Buddhism a hatred in his Diwan where he wrote the verse cycle on the war against Uighur Buddhists. Buddhist origin words like toyin (a cleric or priest) and Burxān or Furxan[35][36] (meaning Buddha,[37][38][39] acquiring the generic meaning of "idol" in the Turkic language of Kashgari) had negative connotations to Muslim Turks.[40][41]

The wars against the Buddhist, Shamanist, and Manichean Uyghurs were considered a Jihad by the Kara-Khanids.[42][43][44]

Islam was the enemy of the Christian and Buddhist Turfan Uyghur Kingdom.[45]

The Imams and soldiers who died in the battles against the Uyghur Buddhists and Khotan Buddhist Kingdom during the Tarim Basin's Islamification at the hands of the Karakhanids are revered as saints.[46]

It was possible the Muslims drove some Uyghur Buddhist monks towards taking asylum in the Western Xia dynasty.[47]

Mongol rule

Alans were recruited into the Mongol forces with one unit called "Right Alan Guard" which was combined with "recently surrendered" soldiers, Mongols, and Chinese soldiers stationed in the area of the former Kingdom of Qocho and in Besh Balikh the Mongols established a Chinese military colony led by Chinese general Qi Kongzhi.[48]

The kingdom was a Buddhist state, with both state-sponsored Mahayana Buddhism and Manichaeism, and was a center of Uyghur culture. The Uyghurs sponsored the construction of many of the temple-caves in what is now Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves. They abandoned the Old Turkic alphabet and adopted and modified the Sogdian alphabet, which later came to be known as the Old Uyghur alphabet.[49] The Idiquts (the title of the Qocho rulers) ruled independently until they become a vassal state of the Qara Khitai (Chinese: Western Liao). In 1209, the Kara-Khoja ruler Baurchuk Art Tekin declared his allegiance to the Mongols under Genghis Khan and the kingdom existed as a vassal state until 1335. After submitting to the Mongols, the Uyghurs went into the service of the Mongol rulers as bureaucrats, providing the expertise that the initially illiterate nomads lacked.[50] Qocho continued exist as a vassal to the Mongols of the Yuan dynasty, and were allied to the Yuan against the Chagatai Khanate.

When the Mongols placed the Uyghurs of the Kingdom of Qocho over the Koreans at the court the Korean King objected, then the Mongol Emperor Kublai Khan rebuked the Korean King, saying that the Uyghur King of Qocho was ranked higher than the Karluk Kara-Khanid ruler, who in turn was ranked higher than the Korean King, who was ranked last, because the Uyghurs surrendered to the Mongols first, the Karluks surrendered after the Uyghurs, and the Koreans surrendered last, and that the Uyghurs surrendered peacefully without violently resisting.[51][52]

A hybrid court was used when Han Chinese and Uyghurs were in involved in legal issues.[53]

Conquest by Muslim Chagatais

The Buddhist Uyghurs of the Kingdom of Qocho and Turfan were converted to Islam by conquest during a ghazat (holy war) at the hands of the Muslim Chagatai Khanate ruler Khizr Khoja (r. 1389-1399). Qocho and Turfan were viewed as part of "Khitay",[54] which was a name for China.[55] The 1390s war by Kizir Khoja's against the Uyghurs (Huihu) of Qoco (Qocho) is also considered a Jihad. As a consequence of the Jihad, the religion of Islam was forced on Qocho and this resulted in the city of Jiaohe being abandoned.[56] The mujahideen of the Islamic Chagatai Khanate conquered the Uyghur and Hami was purged of the Buddhist religion which was replaced with Islam.[57] The Islamic conversion forced on the Buddhist Hami state was the final event in the Islamization.[42][43][44]

After being converted to Islam, the descendants of the previously-Buddhist Uyghurs in Turfan failed to retain memory of their ancestral legacy and falsely believed that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungar people) were the ones who built Buddhist monuments in their area.[58][59] Buddhist influences still remain among the Turfan Muslims.[60] Since Islam reached them much after Altishahr, personal names of un-Islamic Old Uyghur origin are still used in Qumul and Turfan while people in Altishahr use mostly Islamic names of Persian and Arabic origin.[61]

Anti portrait Muslims had Buddhist portraits obliterated during the wars over hundreds of years in which Buddhism was replaced by Islam. Cherrypicking of history of Xinjiang with the intention of projecting an image of irreligiousity or piousness of Islam in Uyghur culture has been done by people with agendas.[62] Michael Dillon wrote that the 1000s-1100s Islam-Buddhist war are still recalled in the forms of the Khotan Imam Asim Sufi shrine celebration and other Sufi holy site celebrations. Bezeklik's Thousand Buddha Caves are an example of the religiously motivated vandalism against portraits of religious and human figures.[63]

Buddhist murals at the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves were damaged by local Muslim population whose religion proscribed figurative images of sentient beings, the eyes and mouths in particular were often gouged out. Pieces of murals were also broken off for use as fertilizer by the locals.[64]

The Uyghurs of Taoyuan are the remnants of Uyghurs from Turpan from the Kingdom of Qocho.

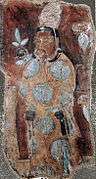

Images of Buddhist and Manichean Uyghurs

Uyghur Khagan

Uyghur Khagan Uyghur king from Turfan

Uyghur king from Turfan Uyghur Prince from the Bezeklik murals

Uyghur Prince from the Bezeklik murals Uyghur noble from the Bezeklik murals

Uyghur noble from the Bezeklik murals Uyghur noble from the Bezeklik murals

Uyghur noble from the Bezeklik murals Uyghur Princesses from the Bezeklik murals

Uyghur Princesses from the Bezeklik murals Uyghur Princes from the Bezeklik murals

Uyghur Princes from the Bezeklik murals Uyghur donor from the Bezeklik murals

Uyghur donor from the Bezeklik murals Uyghur Manichaean Electae from Qocho

Uyghur Manichaean Electae from Qocho Uyghur Manichaean clergymen from Qocho

Uyghur Manichaean clergymen from Qocho Manicheans from Qocho

Manicheans from Qocho Mural from a Nestorian temple in Qocho

Mural from a Nestorian temple in Qocho

See also

- Turkic peoples

- Tocharians

- Sogdia

- Timeline of the Turkic peoples (500–1300)

- List of Turkic dynasties and countries

- Kara Del

- Ming–Turpan conflict

- History of the Uyghur people

- History of Xinjiang

- Gansu Uyghur Kingdom

References

- ↑ Éric Trombert; Étienne de La Vaissière (2005). Les sogdiens en Chine. École française d'Extrême-Orient. p. 299. ISBN 978-2-85539-653-8.

- ↑ Hansen, Valerie. "Les Sogdiens en Chine" (PDF).

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Stephen F. Teiser (1 April 2003). The Scripture on the Ten Kings: And the Making of Purgatory in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2776-2.

- ↑ Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2006). Peoples of Western Asia. p. 364.

- ↑ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. p. 280.

- ↑ Borrero, Mauricio (2009). Russia: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present. p. 162.

- ↑ Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies (1996). Cultural contact, history and ethnicity in inner Asia: papers presented at the Central and Inner Asian Seminar, University of Toronto, March 4, 1994 and March 3, 1995. Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies. p. 137.

- ↑ Sir Charles Eliot (4 January 2016). Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch. Sai ePublications & Sai Shop. pp. 1075–. GGKEY:4TQAY7XLN48.

- ↑ Baij Nath Puri (1987). Buddhism in Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-81-208-0372-5.

- ↑ Charles Eliot; Sir Charles Eliot (1998). Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch. Psychology Press. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-0-7007-0679-2.

- ↑ Millward 2007, p. 46.

- ↑ Millward 2007, p. 48-49.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ Peter B. Golden (2011), Central Asia in World History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 47, ISBN 978-0-19-515947-9.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ TAKATA, Tokio. "The Chinese Language in Turfan with a special focus on the Qieyun fragments" (PDF). Institute for Research in Humanities, Kyoto University: 7–9. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ Abdurishid Yakup (2005). The Turfan Dialect of Uyghur. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 180–. ISBN 978-3-447-05233-7.

- ↑ Gorelova, Liliya (2002). Manchu Grammar. Brill. p. 49. ISBN 978-90-04-12307-6.

- ↑ Millward 2007, p. 43.

- ↑ Modern Chinese Religion I (2 vol.set): Song-Liao-Jin-Yuan (960-1368 AD). BRILL. 8 December 2014. pp. 895–. ISBN 978-90-04-27164-7.

- ↑ Dust in the Wind: Retracing Dharma Master Xuanzang's Western Pilgrimage. Rhythms Monthly. 2006. pp. 479–. ISBN 978-986-81419-8-8.

- ↑ Edmund Herzig (30 November 2014). The Age of the Seljuqs. I.B.Tauris. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-1-78076-947-9.

- ↑ Edmund Herzig (30 November 2014). The Age of the Seljuqs. I.B.Tauris. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-1-78076-947-9.

- ↑ Devin DeWeese (1 November 2010). Islamization and Native Religion in the Golden Horde: Baba TŸkles and Conversion to Islam in Historical and Epic Tradition. Penn State Press. pp. 152–. ISBN 0-271-04445-4.

- ↑ Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (1980). Harvard Ukrainian studies. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. p. 159.

- ↑ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- ↑ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- ↑ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- ↑ Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (1980). Harvard Ukrainian studies. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. p. 160.

- ↑ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- ↑ Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (1980). Harvard Ukrainian studies. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. p. 151.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20151118063834/http://projects.iq.harvard.edu/huri/files/viii-iv_1979-1980_part1.pdf p. 160.

- ↑ Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (1980). Harvard Ukrainian studies. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. p. 160.

- ↑ Giovanni Stary (1996). Proceedings of the 38th Permanent International Altaistic Conference (PIAC): Kawasaki, Japan, August 7-12, 1995. Harrassowitz Verlag in Kommission. pp. 17, 27. ISBN 978-3-447-03801-0.

- ↑ James Russell Hamilton (1971). Conte bouddhique du bon et du mauvais prince. Éditions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique. p. 114.

- ↑ Linguistica Brunensia. Masarykova univerzita. 2009. p. 66.

- ↑ Egidius Schmalzriedt; Hans Wilhelm Haussig (2004). Die mythologie der mongolischen volksreligion. Klett-Cotta. p. 956. ISBN 978-3-12-909814-1.

- ↑ http://www.asianpa.net/assets/upload/articles/LZnCyNgsTym1unXG.pdf https://www.asianpa.net/assets/upload/articles/LZnCyNgsTym1unXG.pdf https://tr.wikisource.org/wiki/Div%C3%A2n-%C4%B1_L%C3%BCgati%27t-T%C3%BCrk_dizini http://www.hasmendi.net/Genel%20Dosyalar/KASGARLI_MAHMUT_LUGATI.pdf http://www.slideshare.net/ihramcizade/divan-lugatitrk http://www.philology.ru/linguistics4/tenishev-97a.htm http://www.biligbitig.org/divanu-lugat-turk http://docplayer.biz.tr/5169964-Divan-i-luqat-it-turk-dizini.html http://turklukbilgisi.com/sozluk/index.php/list/7/,F.xhtml https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=354765 https://www.ceeol.com/content-files/document-355264.pdf http://divanilugatitturk.blogspot.com/2016/01/c-harfi-divanu-lugat-it-turk-sozlugu_1.html https://plus.google.com/108758952067162862352 https://plus.google.com/108758952067162862352/posts/Ww2ce29Qfkz

- ↑ Dankoff, Robert (Jan–Mar 1975). "Kāšġarī on the Beliefs and Superstitions of the Turks". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 95 (1): 69. JSTOR 599159. doi:10.2307/599159.

- ↑ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- 1 2 Jiangping Wang (12 October 2012). 中国伊斯兰教词汇表. Routledge. pp. xvi–. ISBN 978-1-136-10650-7.

- 1 2 Jiangping Wang (12 October 2012). Glossary of Chinese Islamic Terms. Routledge. pp. xvi–. ISBN 978-1-136-10658-3.

- 1 2 Jianping Wang (2001). 中国伊斯兰教词汇表. Psychology Press. pp. xvi–. ISBN 978-0-7007-0620-4.

- ↑ Millward (2007), p. 43.

- ↑ David Brophy (4 April 2016). Uyghur Nation: Reform and Revolution on the Russia-China Frontier. Harvard University Press. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-0-674-97046-5.

- ↑ Ruth W. Dunnell (January 1996). The Great State of White and High: Buddhism and State Formation in Eleventh-Century Xia. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-0-8248-1719-0.

- ↑ Morris Rossabi (1983). China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th Centuries. University of California Press. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-0-520-04562-0.

- ↑ Souček 2000, pp. 49, 79.

- ↑ Souček 2000, p. 105.

- ↑ Morris Rossabi (1983). China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th Centuries. University of California Press. pp. 247–. ISBN 978-0-520-04562-0.

- ↑ Haw 2014, p. 4.

- ↑ Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John King Fairbank (25 November 1994). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb; Bernard Lewis; Johannes Hendrik Kramers; Charles Pellat; Joseph Schacht (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. p. 677.

- ↑ Journal of the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Archaeology Publications. 2002. p. 72.

- ↑ Dust in the Wind: Retracing Dharma Master Xuanzang's Western Pilgrimage. Rhythms Monthly. 2006. pp. 480–. ISBN 978-986-81419-8-8.

- ↑ Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb; Bernard Lewis; Johannes Hendrik Kramers; Charles Pellat; Joseph Schacht (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. p. 677.

- ↑

- ↑ Silkroad Foundation, Adela C.Y. Lee. "Viticulture and Viniculture in the Turfan Region".

- ↑ Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2007). Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 113–. ISBN 978-0-7546-7041-4.

- ↑ Michael Dillon (1 August 2014). Xinjiang and the Expansion of Chinese Communist Power: Kashgar in the Early Twentieth Century. Routledge. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-1-317-64721-8.

- ↑ Michael Dillon (1 August 2014). Xinjiang and the Expansion of Chinese Communist Power: Kashgar in the Early Twentieth Century. Routledge. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-1-317-64721-8.

- ↑ Whitfield, Susan (2010). "A place of safekeeping? The vicissitudes of the Bezeklik murals". In Agnew, Neville. Conservation of ancient sites on the Silk Road: proceedings of the second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People's Republic of China (PDF). Getty Publications. pp. 95–106. ISBN 978-1-60606-013-1.

Bibliography

- Asimov, M.S. (1998), History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Part One The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO Publishing

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Benson, Linda (1998), China's last Nomads: the history and culture of China's Kazaks, M.E. Sharpe

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2000), The Age of Achievement: A.D. 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century - Vol. 4, Part II : The Achievements (History of Civilizations of Central Asia), UNESCO Publishing

- Bughra, Imin (1983), The history of East Turkestan, Istanbul: Istanbul publications

- Drompp, Michael Robert (2005), Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History, Brill

- Golden, Peter B. (2011), Central Asia in World History, Oxford University Press

- Haywood, John (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492, Barnes & Noble

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1964), The Chinese, their history and culture, Volumes 1-2, Macmillan

- Mackerras, Colin (1990), "Chapter 12 - The Uighurs", in Sinor, Denis, The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, pp. 317–342, ISBN 0 521 24304 1

- Mergid, Toqto'a (1344), History of Liao

- Millward, James A. (2007), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press

- Mackerras, Colin, The Uighur Empire: According to the T'ang Dynastic Histories, A Study in Sino-Uighur Relations, 744-840. Publisher: Australian National University Press, 1972. 226 pages, ISBN 0-7081-0457-6

- Rong, Xinjiang (2013), Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang, Brill

- Sinor, Denis (1990), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9

- Soucek, Svat (2000), A History of Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press

- Xiong, Victor (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0810860538

- Xue, Zongzheng (1992), Turkic peoples, 中国社会科学出版社

Further reading

- Chotscho : vol.1

- Moriyasu Takao, 'The Sha-Chou [Dunhuang] Uighurs and the West Uighur Kingdo', Acta Asiatica: Bulletin of the Institute of Eastern Culture, No. 78