Kampilan

| Kampilan - Manardas ᜃᜋ᜔ᜉᜒᜎᜈ᜔ | |

|---|---|

|

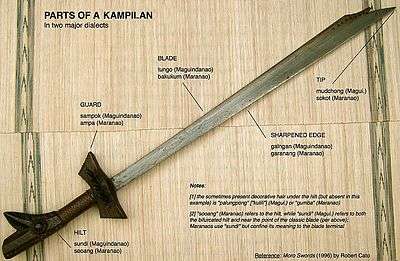

Parts of the kampílan, written in Maguindanao and Maranao languages of Mindanao. | |

| Type | Sword |

| Place of origin | Philippines |

| Service history | |

| In service | Ancient barangays Rajahnate of Cebu Madja-as Tondo Namayan Maynila Rajahnate of Butuan Sultanate of Maguindanao |

| Used by | Kapampangans, Ilokanos, Visayans, Moros (Illanun, Maguindanao, Maranao, Sulu), Bajau |

| Wars |

Majapahit-Luzon wars Bruneian Invasion of Tondo Battle of Mactan Moro wars |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 90-100cm |

|

| |

| Blade type | Single edge |

| Hilt type | Ivory , Wood , Gold |

| Scabbard/sheath | Wood |

The kampilan is a type of single-edged long sword, traditionally used by various ethnic groups in the Philippines archipelago.

The kampilan (Baybayin: ᜃᜋ᜔ᜉᜒᜎᜈ᜔ Abecedario: cámpilán) has a distinct profile, with the tapered blade being much broader and thinner at the point than at its base, sometimes with a protruding spikelet along the flat side of the tip and a bifurcated hilt which is believed to represent a mythical creature's open mouth.[1]

The Maguindanao and the Maranao of mainland Mindanao preferred this weapon as opposed to the Tausūg of Sulu who favoured the barung. The Kapampangan name of the Kampilan was Talibong and the hilt on the Talibong represented the dragon Naga, however the creature represented varies between different ethnic groups. Its use by the Illocanos have also been seen in various ancient records. Pieces of Visayan kampilans are distinguished by their Mindanao counterparts by the way hilts are made. The native Meranau name of the Kampilan was Kifing, while the Iranun language it is known as Parang Kampilan.[2]

A notable wielder of the kampílan was Datu Lapu-Lapu (the king of Mactan) and his warriors, who defeated the Spaniards and killed Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan at the Battle of Mactan on April 27, 1521.[1][3][4]

The kampílan was earliest mentioned in ancient Filipino epics in Hiligaynon Hinilawod from the Visayas and Ilocano Biag ni Lam-Ang from Luzon. This particular design of sword was not uncommon among the various ethnic tribes throughout the pre-Hispanic Philippine archipelago. the early Today, the kampílan is portrayed in Filipino art and ancient tradition.

In Borneo, the Dayak people are also known to forge kampilan.[5] The officers who bears the royal regalia of the Sultan of Brunei such as the Panglima Agsar who carries the royal weapons of kelasak (shield) and kampilan, whereas the Panglima Raja carries the pemuras (royal gun) and kampilan.[6]

Physical description

Among Filipino swords, the most distinguishing characteristic of the Kampilan is its huge size. At about 36 to 40 inches (90 to 100 cm) long, it is much larger than other Filipino swords,[3] and is thought to be the longest,[4] though smaller versions (sometimes called the kampilan bolo)[7] exist. A notable exception would be the panabas, another Philippine longsword, of which an unusually large example could measure up to four feet in length.[8]

Related to the klewang, the blade is narrow near the hilt and it gradually swells in width into an almost trapezoidal profile at the end. The blades are often laminated with various styles of tip. Kampílan blades often have holes near the tip that are sometimes filled with brass. Rarer still are specimens that have tips exhibiting a kris-like fretwork, while others have engravings down the entire blade. Although the kampílan can be used with one hand, it is primarily a two-handed sword. At times the hilt was bound to the hand by a talismanic piece of cloth to prevent slippage. Sometimes a chain mail covering was attached to prevent the hand from injury. Almost all kampílan originally had large metal staples protruding from the cross guard above the grip. Hilts were made of hardwood, but expensive examples that belonged to datus are covered in silver sheet or are entirely manufactured of expensive materials such as ivory or bone.

Blade

The laminated steel blade of the kampílan is single-edged, and made from Damascus steel pattern welding process[9][10] and is easily identified by its tapered profile, narrowest near the hilt and gently widening until its truncated point. The blade's spikelet has led to the description of the kampílan in some documents as "dual-tipped" or "double-tipped".[1][3][11][11]

Sheath or scabbard

The scabbard is usually made of cheap wood and is bound with simple rattan or fibre lashings. When the sword needs to be used immediately, the sword bearer will simply strike with the sheathed sword and the blade will cut through the lashings, thereby effecting a quick, tactical strike without the need to unsheathe the sword.

Scabbards are unadorned and are often disposable when going into battle. Some scabbards were also made of bamboo or were made with a handle that allowed half of the scabbard to serve as a small shield.

Hilt

The hilt is quite long in order to counterbalance the weight and length of the blade and is made of hardwood.[1] As with the blade, the design of the hilt's profile is relatively consistent from blade to blade, combining to make the kampílan an effective combat weapon.

The complete tang of the kampílan disappears into a crossguard, which is often decoratively carved in an okir (geometric or flowing) pattern.[1] The guard prevents the enemy's weapon from sliding all the way down the blade onto bearer's hand and also prevents the bearer's hand from sliding onto the blade while thrusting.

The most distinctive design element of the hilt is the Pommel, which is shaped to represent a creature's wide open mouth. The represented creature varies from sword to sword depending on the culture. Sometimes it is a real animal such as a monitor lizard or a crocodile,[3] but more often the animal depicted is mythical, with the nāga and the bakonawa being popular designs.[1][4] Some kampílan also have animal or human hair tassels attached to the hilt as a form of decoration.[1]

Usage

The kampílan is a weapon used for warfare, used either in small skirmishes or large-scale encounters.[4] According to Philippine historical documents, the kampílan was widely used by chieftains and warriors for battle and as a headhunting sword. The most famous use of kampilans in warfare was in the Battle of Mactan.[3][4]

Publications

- Whittington, Jeff. "armory:knives". Peoples of the Philippines: Filipino Arts and Crafts. The C.E. Smith Museum of Anthropology. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- Greaves, Ian; Jose Albovias Jr; Federico Malibago. "Sandata - The Edged Weapons of the Philippines". History of Steel in Eastern Asia. Macao Museum of Art. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- "kampilan (subheading)". History of Steel in Eastern Asia. Macao Museum of Art. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Kampilan". Malay World Edged Weapons. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ Mamitua Saber, Dionisio G. Orellana (1977). Comparative Notes On Museum Exhibits In Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Macao, And The Philippines: A Report To The Ford Foundation On Travelling Symposium For Southeast Asia Museum Development, April-May, 1971. Aga Khan Museum, Mindanao State University. ASIN B0007BP4DA.

- 1 2 3 4 5 http://www.traditionalfilipinoweapons.com/Kampilan.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 http://www.marcialtirada.net/traditional_filipino_weapons

- ↑ Bernard Dorléans (2006). Orang Indonesia Dan Orang Prancis: Dari Abad XVI Sampai Dengan Abad XX. Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. ISBN 978-979-9100-50-4.

- ↑ Siti Norkhalbi Haji Wahsalfelah (2007). Textiles and Identity in Brunei Darussalam. White Lotus Press. ISBN 974-480-094-1.

- ↑ http://traditionalfilipinoweapons.com/KampilanBolo.html

- ↑ http://traditionalfilipinoweapons.com/Panabas.htm

- ↑ Maryon, Herbert (February 1960). "Pattern-Welding and Damascening of Sword-Blades—Part 1: Pattern-Welding". Studies in Conservation. 5 (1): 25–37. JSTOR 1505063. doi:10.2307/1505063.

- ↑ Maryon, Herbert (May 1960). "Pattern-Welding and Damascening of Sword-Blades—Part 2: The Damascene Process". Studies in Conservation. 5 (2): 52–60. JSTOR 1504953. doi:10.2307/1504953.

- 1 2 Raiders of the Sulu Sea (Documentary). Oakfilms3, History Channel Asia. Retrieved 2009-02-08.