Mount Kailash

| Mount Kailash | |

|---|---|

|

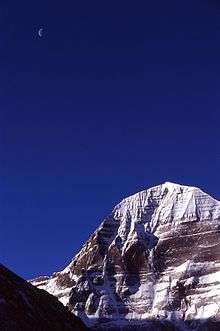

The north face of Mount Kailash | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 6,638 m (21,778 ft) |

| Prominence | 1,319 m (4,327 ft) |

| Coordinates | 31°4′0″N 81°18′45″E / 31.06667°N 81.31250°ECoordinates: 31°4′0″N 81°18′45″E / 31.06667°N 81.31250°E |

| Geography | |

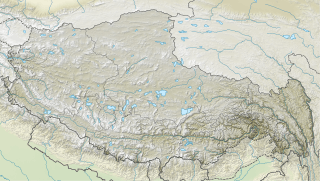

Mount Kailash | |

| Parent range | Transhimalaya |

Mount Kailash (also Mount Kailas; Kangrinboqê or Gang Rinpoche (Tibetan: གངས་རིན་པོ་ཆེ; Chinese: 冈仁波齐峰 (simplified); Chinese: 岡仁波齊峰 (traditional)) is a peak in the Kailash Range (Gangdisê Mountains), which forms part of the Transhimalaya in the Tibetan Autonomous Region of China.

Mt. Kailash lies near the source of some of the longest rivers in Asia: the Indus River, Sutlej River, Brahmaputra River, and Karnali River (a tributary of the Ganges River). It is considered a sacred place in four religions: Bön, Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism. The mountain lies near Lake Manasarovar and Lake Rakshastal.

Name

The mountain is known as Kailāsa (कैलास) in Sanskrit.[1][2] The name may be derived from the word kelāsa (केलास), which means "crystal".[3] In his Tibetan-English dictionary, Chandra (1902: p. 32) identifies the entry for 'kai la sha' (Wylie: kai la sha ) which is a loan word from Sanskrit 'kailāsa' (Devanagari: कैलास).[4]

The Tibetan name for the mountain is Gangs Rin-po-che. Gangs or Kang is the Tibetan word for snow peak analogous to alp or hima; rinpoche is an honorific meaning "precious one" so the combined term can be translated "precious jewel of snows".

- "Tibetan Buddhists call it Kangri Rinpoche; 'Precious Snow Mountain'. Bon texts have many names: Water's Flower, Mountain of Sea Water, Nine Stacked Swastika Mountain. For Hindus, it is the home of the mountain god Shiva and a symbol of his power symbol om; for Jains it is where their first Tirthankara was enlightened; for Buddhists, the navel of the universe; and for adherents of Bon, the abode of the sky goddess Sipaimen."[5]

Another local name for the mountain is Tisé mountain, which derives from ti tse in the Zhang-Zhung language, meaning "water peak" or "river peak", connoting the mountain's status as the source of the mythical Lion, Horse, Peacock and Elephant Rivers, and in fact the Indus, Yarlung Tsangpo/Dihang/Brahmaputra, Karnali and Sutlej all begin in the Kailash-Lake Manasarovara region.[6]

Religious significance

In Hinduism

| Part of a series on |

| Shaivism |

|---|

|

|

Scriptures and texts |

|

Schools

Saiddhantika Non - Saiddhantika

|

|

Others

|

|

|

According to Hinduism, Lord Shiva, the god of gods, resides at the summit of a legendary mountain named Kailāsa, where he sits in a state of perpetual meditation along with his wife Pārvatī. He is at once the Lord of Yoga and therefore the ultimate renunciate ascetic, yet he is also the divine master of Tantra.[7]

According to Charles Allen, one description in the Vishnu Purana of the mountain states that its four faces are made of crystal, ruby, gold, and lapis lazuli.[8] It is a pillar of the world and is located at the heart of six mountain ranges symbolizing a lotus.[8]

In Jainism

In Jainism, Kailash is also known as Meru Parvat or Sumeru. Ashtapada, the mountain next to Mt. Kailash, is the site where the first Jain Tirthankara, Rishabhadeva, attained Nirvana/moksa (liberation).[9]

In Buddhism

Tantric Buddhists believe that Mount Kailash is the home of the Buddha Demchok (also known as Demchog or Chakrasamvara),[10] who represents supreme bliss.

There are numerous sites in the region associated with Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava), whose tantric practices in holy sites around Tibet are credited with finally establishing Buddhism as the main religion of the country in the 7th–8th century AD.[11]

It is said that Milarepa (c. 1052 – c. 1135 AD), champion of Tantric Buddhism, arrived in Tibet to challenge Naro Bön-chung, champion of the Bön religion of Tibet. The two magicians engaged in a terrifying sorcerers' battle, but neither was able to gain a decisive advantage. Finally, it was agreed that whoever could reach the summit of Kailash most rapidly would be the victor. While Naro Bön-chung sat on a magic drum and soared up the slope, Milarepa's followers were dumbfounded to see him sitting still and meditating. Yet when Naro Bön-chung was nearly at the top, Milarepa suddenly moved into action and overtook him by riding on the rays of the Sun, thus winning the contest. He did, however, fling a handful of snow on to the top of a nearby mountain, since known as Bönri, bequeathing it to the Bönpo and thereby ensuring continued Bönpo connections with the region.[12][13][14]

In Bön

The Bön, a religion native to Tibet, maintain that the entire mystical region and the nine-story Swastika Mountain are the seat of all spiritual power.

Pilgrimage

Every year, thousands make a pilgrimage to Kailash, following a tradition going back thousands of years. Pilgrims of several religions believe that circumambulating Mount Kailash on foot is a holy ritual that will bring good fortune. The peregrination is made in a clockwise direction by Hindus and Buddhists_Jain. Followers of the Jain and Bönpo religions circumambulate the mountain in a counterclockwise direction. The path around Mount Kailash is 52 km (32 mi) long.

Some pilgrims believe that the entire walk around Kailash should be made in a single day, which is not considered an easy task. A person in good shape walking fast would take perhaps 15 hours to complete the 52 km trek. Some of the devout do accomplish this feat, little daunted by the uneven terrain, altitude sickness and harsh conditions faced in the process. Indeed, other pilgrims venture a much more demanding regimen, performing body-length prostrations over the entire length of the circumambulation: The pilgrim bends down, kneels, prostrates full-length, makes a mark with his fingers, rises to his knees, prays, and then crawls forward on hands and knees to the mark made by his/her fingers before repeating the process. It requires at least four weeks of physical endurance to perform the circumambulation while following this regimen. The mountain is located in a particularly remote and inhospitable area of the Tibetan Himalayas. A few modern amenities, such as benches, resting places and refreshment kiosks, exist to aid the pilgrims in their devotions. According to all religions that revere the mountain, setting foot on its slopes is a dire sin. It is a popular belief that the stairways on Mount Kailash lead to heaven.

Following the political and border disturbances across the Chinese-Indian boundary, pilgrimage to the legendary abode of Shiva was stopped from 1954 to 1978. Thereafter, a limited number of Indian pilgrims have been allowed to visit the place, under the supervision of the Chinese and Indian governments either by a lengthy and hazardous trek over the Himalayan terrain, travel by land from Kathmandu or from Lhasa where flights from Kathmandu are available to Lhasa and thereafter travel over the great Tibetan plateau by car. The journey takes four night stops, finally arriving at Darchen at elevation of 4,600 m (15,100 ft), small outpost that swells with pilgrims at certain times of year. Despite its minimal infrastructure, modest guest houses are available for foreign pilgrims, whereas Tibetan pilgrims generally sleep in their own tents. A small regional medical center serving far-western Tibet and funded by the Swiss Ngari Korsum Foundation was built here in 1997.

Walking around the mountain—a part of its official park—has to be done on foot, pony or yak, taking some three days of trekking starting from a height of around 15,000 ft (4,600 m) past the Tarboche (flagpole) to cross the Drölma pass 18,200 ft (5,500 m), and encamping for two nights en route. First, near the meadow of Dirapuk gompa, some 2 to 3 km (1.2 to 1.9 mi) before the pass and second, after crossing the pass and going downhill as far as possible (viewing Gauri Kund in the distance).

Geology

The region around Mount Kailash and the Indus headwaters area is typified by wide scale faulting of metamorphosed late Cretaceous to mid Cenozoic sedimentary rocks which have been intruded by igneous Cenozoic granitic rocks. Mt. Kailash appears to be a metasedimentary roof pendant supported by a massive granite base. The Cenozoic rocks represent offshore marine limestones deposited before subduction of the Tethys oceanic crust. These sediments were deposited on the southern margin of the Asia block during subduction of the Tethys oceanic crust prior to the collision between the Indian and Asian continents.[15][16]

Mountaineering

In 1926, Hugh Ruttledge studied the north face, which he estimated was 6,000 ft (1,800 m) high and "utterly unclimbable"[17] and thought about an ascent of the northeast ridge, but he ran out of time. Ruttledge had been exploring the area with Colonel R. C. Wilson, who was on the other side of the mountain with his Sherpa named Tseten. According to Wilson, Tseten told Wilson, "'Sahib, we can climb that!' ... as he too saw that this [the SE ridge] represented a feasible route to the summit."[18] Further excerpts from Wilson's article in the Alpine Journal (vol. 40, 1928) show that he was serious about climbing Kailash, but he also ran out of time. Herbert Tichy was in the area in 1936, attempting to climb Gurla Mandhata. When he asked one of the Garpons of Ngari whether Kailash was climbable, the Garpon replied, "Only a man entirely free of sin could climb Kailash. And he wouldn't have to actually scale the sheer walls of ice to do it – he'd just turn himself into a bird and fly to the summit."[19] Reinhold Messner was given the opportunity by the Chinese government to climb in the mid-1980s but he declined.[20]

In 2001 the Chinese gave permission for a Spanish team to climb the peak, but in the face of international disapproval the Chinese decided to ban all attempts to climb the mountain.[20] Reinhold Messner, who condemned the Spanish plans, said "If we conquer this mountain, then we conquer something in people's souls....I would suggest they go and climb something a little harder. Kailas is not so high and not so hard."[21]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Monier-Williams Sanskrit Dictionary, page 311 column 3

- ↑ Entry for कैलासः in Apte Sanskrit-English Dictionary

- ↑ Entry for केलासः in Apte Sanskrit-English Dictionary

- ↑ Sarat Chandra Das (1902). Tibetan-English Dictionary with Sanskrit Synonyms. Calcutta, India: Bengal Secretariat Book Depot, page 32.

- ↑ Albinia (2008), p. 288. abc

- ↑ Camaria, Pradeep (1996), Kailash Manasarovara on the Rugged Road to Revelation, New Delhi: Abhinav, retrieved 11 June 2010

- ↑ "Mt. Kailash".

- 1 2 Allen, Charles. (1982). A Mountain in Tibet, pp. 21–22. André Deutsch. Reprint: 1991. Futura Publications, London. ISBN 0-7088-2411-0.

- ↑ "To heaven and back – Times Of India". Articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com. 2012-01-11. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- ↑ "Heruka Chakrasamvara". Khandro.net. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- ↑ The Sacred Mountain, pp. 39, 33, 35, 225, 280, 353, 362–363, 377–378

- ↑ The Sacred Mountain, pp. 31, 33, 35

- ↑ The World's Most Mysterious Places Published by Reader's Digest ISBN 0-276-42217-1 pg.85

- ↑ The Sacred Mountain, pp. 25–26

- ↑ Geology and Geography of the Mt. Kailash area and Indus River headwaters in southwestern Tibet Pete Winn , Science Director Earth Science Expeditions. Accessed January 2014.

- ↑ Plate Tectonic & northern Pacific Accessed January 2014.

- ↑ The Sacred Mountain, p. 120

- ↑ The Sacred Mountain, p. 116

- ↑ The Sacred Mountain, p. 129

- 1 2 "China to Ban Expeditions on Mt Kailash". tew.org. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ "Scaling a Mountain to Destroy The Holy Soul of Tibetans". tew.org. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

Further reading

- Albinia, Alice. (2008) Empires of the Indus: The Story of a River. First American Edition (2010) W. W. Norton & Company, New York. ISBN 978-0-393-33860-7.

- Nomachi, Kazuyoshi. Tibet. Boston: Shambhala, 1997.

- Thurman, Robert and Tad Wise, Circling the Sacred Mountain: A Spiritual Adventure Through the Himalayas. New York: Bantam, 1999. ISBN 0-553-37850-3 — Tells the story of a Western Buddhist making the trek around Mount Kailash.

- Snelling, John. (1990). The Sacred Mountain: The Complete Guide to Tibet's Mount Kailas. 1st edition 1983. Revised and enlarged edition, including: Kailas-Manasarovar Travellers' Guide. Forwards by H.H. the Dalai Lama of Tibet and Christmas Humphreys. East-West Publications, London and The Hague. ISBN 0-85692-173-4.

- (Elevation) Chinese Snow Map "Kangrinboqe", published by the Lanzhou Institute of Glaciology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

- Allen, Charles (1982) A Mountain in Tibet: The Search for Mount Kailas and the Sources of the Great Rivers of Asia. (London, André Deutsch).

- Allen, Charles. (1999). The Search for Shangri-La: A Journey into Tibetan History. Little, Brown and Company. Reprint: Abacus, London. 2000. ISBN 0-349-11142-1.

- "A Tibetan Guide for Pilgrimage to Ti-se (Mount Kailas) and mTsho Ma-pham (Lake Manasarovar)." Toni Huber and Tsepak Rigzin. In: Sacred Spaces and Powerful Places In Tibetan Culture: A Collection of Essays. (1999) Edited by Toni Huber, pp. 125–153. The Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala, H.P., India. ISBN 81-86470-22-0.

- Stein, R. A. (1961). Les tribus anciennes des marches Sino-Tibétaines: légends, classifications et histoire. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris. (In French)

- Johnson, Russell, and Moran, Kerry. (1989). The Sacred Mountain of Tibet: On Pilgrimage to Kailas. Park Street Press, Rochester, Vermont. ISBN 0-89281-325-3.

- Govinda, Lama Anagarika. (1966). The Way of the White Clouds: A Buddhist Pilgrim in Tibet. Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, Colorado. Reprint with foreword by Peter Matthiessen: Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boston, Massachusetts. 1988. ISBN 0-87773-007-5

- Thubron, Colin. (2011). "To a Mountain in Tibet." Chatto & Windus, London. ISBN 978-0-7011-8380-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mount Kailash. |

- Walk around Kailash Video and still images illustrating the pilgrimage route around Mt. Kailash and parts of Lake Manasarovar, including the Saga Dawa full moon festival celebrating the life of the Buddha.