KLM

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Founded | 7 October 1919 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hubs | Amsterdam Airport Schiphol | ||||||

| Frequent-flyer program | Flying Blue | ||||||

| Alliance | SkyTeam | ||||||

| Subsidiaries | |||||||

| Fleet size | 115 (161 inc Cargo and Cityhopper) | ||||||

| Destinations | 145 | ||||||

| Company slogan | Journeys of Inspiration | ||||||

| Parent company | Air France–KLM | ||||||

| Headquarters | Amstelveen, Netherlands | ||||||

| Key people |

| ||||||

| Revenue | €9.80 billion (2016)[4] | ||||||

| Operating income | €691 million (2016)[5] | ||||||

| Employees | 35,488 (2015) | ||||||

| Website | klm.com | ||||||

KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, legally Koninklijke Luchtvaart Maatschappij N.V.,[6] is the flag carrier airline of the Netherlands.[7] KLM is headquartered in Amstelveen, with its hub at nearby Amsterdam Airport Schiphol. It is part of the Air France–KLM group, and is a member of the SkyTeam airline alliance. KLM was founded in 1919; it is the oldest airline in the world still operating under its original name and had 32,505 employees as of 2013.[8] KLM operates scheduled passenger and cargo services to 145 destinations.

History

Early years

In 1919, a young aviator lieutenant named Albert Plesman sponsored the ELTA aviation exhibition in Amsterdam. The exhibition was a great success; after it closed several Dutch commercial interests intended to establish a Dutch airline, which Plesman was nominated to head.[10] In September 1919, Queen Wilhelmina awarded the yet-to-be-founded KLM its "Royal" ("Koninklijke") predicate.[11] On 7 October 1919, eight Dutch businessmen, including Frits Fentener van Vlissingen, founded KLM—the abbreviation of Koninklijke Luchtvaart Maatschappij ("Royal Aviation Society") as one of the first commercial airline companies. Plesman became its first administrator and director.[10]

The first KLM flight took place on 17 May 1920. KLM's first pilot, Jerry Shaw, flew from Croydon Airport, London, to Amsterdam.[11] The flight was flown using a leased Aircraft Transport and Travel De Haviland DH-16,[11] registration G-EALU, which was carrying two British journalists and some newspapers. In 1920, KLM carried 440 passengers and 22 tons of freight. In April 1921, after a winter hiatus, KLM resumed its services using its own pilots, and Fokker F.II and Fokker F.III aircraft.[11] In 1921, KLM started scheduled services.

KLM's first intercontinental flight took off on 1 October 1924.[11] The final destination was Jakarta (then called 'Batavia'), Java, in the Dutch East Indies; the flight used a Fokker F.VII[11] with registration H-NACC and was piloted by Van der Hoop.[12] In September 1929, regular scheduled services between Amsterdam and Batavia commenced. Until the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, this was the world's longest-distance scheduled service by airplane.[11] By 1926, it was offering flights to Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Brussels, Paris, London, Bremen, Copenhagen, and Malmö, using primarily Fokker F.II and Fokker F.III aircraft.[13]

In 1930, KLM carried 15,143 passengers. The Douglas DC-2 was introduced on the Batavia service in 1934. The first experimental transatlantic KLM flight was between Amsterdam and Curaçao in December 1934 using the Fokker F.XVIII "Snip".[11] The first of the airline's Douglas DC-3 aircraft were delivered in 1936; these replaced the DC-2s on the service via Batavia to Sydney. KLM was the first airline to serve Manchester's new Ringway airport, starting June 1938. KLM was the only civilian airline to receive the Douglas DC-5; the airline used two of them in the West Indies and sold two to the East Indies government, and is thus the only airline to have operated all Douglas 'DC' models other than the DC-1.

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1947 | 454 |

| 1950 | 766 |

| 1955 | 1,485 |

| 1960 | 2,660 |

| 1965 | 3,342 |

| 1971 | 6,330 |

| 1975 | 10,077 |

| 1980 | 14,058 |

| 1985 | 18,039 |

| 1995 | 44,458 |

Second World War

When Germany invaded the Netherlands on 10 May 1940, a number of KLM aircraft—mostly DC-3s and a few DC-2s—were en route to or from the Far East, or were operating services in Europe. Five DC-3s and one DC-2 were taken to England. During the war, these aircraft and crew members flew scheduled passenger flights between Bristol and Lisbon under BOAC registration.

The Douglas DC-3 PH-ALI "Ibis", then registered as G-AGBB, was attacked by the Luftwaffe on 15 November 1942, 19 April 1943, and finally on 1 June 1943 as BOAC Flight 777, killing all passengers and crew. Some KLM aircraft and their crews ended up in the Australia-Dutch East Indies region, where they helped transport refugees from Japanese aggression in that area.

Post-World War II

After the end of the Second World War in August 1945, KLM immediately started to rebuild its network. Since the Dutch East Indies were in a state of revolt, Plesman's first priority was to re-establish KLM's route to Batavia. This service was reinstated by the end of 1945.[10] Domestic and European flights resumed in September 1945, initially with a fleet of Douglas DC-3s and Douglas DC-4s.[11] On 21 May 1946, KLM was the first continental European airline to start scheduled transatlantic flights between Amsterdam and New York City using Douglas DC-4 aircraft.[11] By 1948, KLM had reconstructed its network and services to Africa, North and South America, and the Caribbean resumed.[10]

Long-range, pressurized Lockheed Constellations[14] and Douglas DC-6s[15] joined KLM's fleet in the late 1940s; the Convair 240 short range pressurized twin engined airliner began European flights for the company in late 1948.

During the immediate post-war period, the Dutch government expressed interest in gaining a majority stake in KLM, thus nationalizing it. Plesman wanted KLM to remain a private company under private control; he allowed the Dutch government to acquire a minority stake in the airline.[10] In 1950, KLM carried 356,069 passengers. The expansion of the network continued in the 1950s with the addition of several destinations in western North America.[10] KLM's fleet expanded with the addition of new versions of the Lockheed Constellation and Lockheed Electra, of which KLM was the first European airline to fly.[10]

On 31 December 1953, the founder and president of KLM, Albert Plesman, died at the age of 64.[1][2] He was succeeded as president by Fons Aler.[16] After Plesman's death, the company and other airlines entered a difficult economic period. The conversion to jet aircraft placed a further financial burden on KLM. The Netherlands government increased its ownership of the company to two-thirds, thus nationalizing it. The board of directors remained under the control of private shareholders.[10]

On 25 July 1957, the airline introduced its flight simulator for the Douglas DC-7C – the last KLM aircraft with piston engines – which opened the transpolar route from Amsterdam via Anchorage to Tokyo on 1 November 1958.[11] Each crew flying the transpolar route over the Arctic was equipped with a winter survival kit, including a 7.62 mm selective-fire AR-10 carbine for use against polar bears, in the event the plane was forced down onto the polar ice.[17]

Jet age

Beginning in September 1959, KLM introduced the four-engine turboprop Lockheed Electra onto some of its European and Middle Eastern routes. In March 1960, the airline introduced the first Douglas DC-8 jet into its fleet.[11] In 1961, KLM reported its first year of losses.[10] In 1961, the airline's president Fons Aler was succeeded by Ernst van der Beugel. This change of leadership, however, did not lead to a reversion of KLM's financial difficulties.[10] Van der Beugel resigned as president in 1963 due to health reasons.[18] Horatius Albarda was appointed to succeed Ernst van der Beugel as president of KLM in 1963.[19] Alberda initiated a reorganization of the company, which led to the reduction of staff and air services.[10] In 1965, Alberda died in an air crash and was succeeded as president by Dr. Gerrit van der Wal.[20][21] Van der Wal forged an agreement with the Dutch government that KLM would be once again run as a private company. By 1966, the stake of the Dutch government in KLM was reduced to a minority stake of 49.5%.[10] In 1966, KLM introduced the Douglas DC-9 on European and Middle East routes.

The new terminal buildings at Amsterdam Airport Schiphol opened in April 1967, and in 1968 the stretched Douglas DC-8-63 entered service.[11] With 244 seats, it was the largest airliner at the time. KLM was the first airline to put the higher-gross-weight Boeing 747-200B, powered by Pratt & Whitney JT9D engines, into service in February 1971;[22] this began the airline's use of widebody jets.[11] In March 1971, KLM opened its current headquarters in Amstelveen.[11] In 1972, it purchased the first of several Douglas DC-10 aircraft—McDonnell Douglas's response to Boeing's 747.[10]

In 1973, Sergio Orlandini was appointed to succeed Gerrit van der Wal as president of KLM.[10][23] At the time, KLM, as well as other airlines, had to deal with overcapacity. Orlandini proposed to convert KLM 747s to "combis" that could carry a combination of passengers and freight in a mixed configuration on the main deck of the aircraft.[10] In November 1975, the first of these Boeing 747-200B Combi aircraft were added to the KLM fleet.[11] The airline previously operated DC-8 passenger and freight combi aircraft as well and currently operates Boeing 747-400 combi aircraft.

The oil crisis of 1973, which caused difficult economic conditions, led KLM to seek government assistance in arranging debt refinancing. The airline issued additional shares of stock to the government in return for its money. In the late 1970s, the government's stake had again increased to a majority of 78%, re-nationalizing it.[10] The company management remained under the control of private stakeholders.[11]

1980s and 1990s

In 1980, KLM carried 9,715,069 passengers. In 1983, it reached an agreement with Boeing to convert ten of its Boeing 747-200 combo aircraft to stretched-upper-deck configuration. The work started in 1984 at the Boeing factory in Everett, Washington, and finished in 1986. The converted aircraft were called Boeing 747-200SUD or 747-300, which the airline operated in addition to three newly build Boeing 747-300s. In 1983, KLM took delivery of the first of ten Airbus A310 passenger jets.[10] Sergio Orlandini retired in 1987 and was succeeded as president of KLM by Jan de Soet.[24] In 1986, the Dutch government's shareholding in KLM was reduced to 54.8 percent.[10] It was expected that this share would be further reduced during the decade.[10] The Boeing 747-400 was introduced into KLM's fleet in June 1989.[11]

With the liberalization of the European market, KLM started developing its hub at Amsterdam Airport Schiphol by feeding its network with traffic from affiliated airlines.[10] As part of its development of a worldwide network, KLM acquired a 20% stake in Northwest Airlines in July 1989.[11] In 1990, KLM carried 16,000,000 passengers. KLM president Jan de Soet retired at the end of 1990 and was succeeded in 1991 by Pieter Bouw.[25] In December 1991, KLM was the first European airline to introduce a frequent flyer loyalty program, which was called Flying Dutchman.[11]

Joint venture

In January 1993, the United States Department of Transportation granted KLM and Northwest Airlines anti-trust immunity, which allowed them to intensify their partnership.[11] As of September 1993, the airlines operated their flights between the United States and Europe as part of a joint venture.[11] In March 1994, KLM and Northwest Airlines introduced World Business Class on intercontinental routes.[11] KLM's stake in Northwest Airlines was increased to 25% in 1994.[10]

KLM introduced the Boeing 767-300ER in July 1995.[11] In January 1996, KLM acquired a 26% share in Kenya Airways, the flag-carrier airline of Kenya.[11] In 1997, Pieter Bouw resigned as president of KLM and was succeeded by Leo van Wijk.[26] In August 1998, KLM repurchased all regular shares from the Dutch government to make KLM a private company.[11] On 1 November 1999, KLM founded AirCares, a communication and fundraising platform supporting worthy causes and focusing on underprivileged children.[11]

KLM renewed its intercontinental fleets by replacing the Boeing 767s, Boeing 747-300s, and eventually the McDonnell Douglas MD-11, with Boeing 777-200ERs and Airbus A330-200s. Some 747s were withdrawn from service first. The MD-11s remained in service until October 2014.[27][28] The first Boeing 777 was received on 25 October 2003, while the first Airbus A330-200 was introduced on 25 August 2005.[11]

Air France–KLM merger

On 30 September 2003, Air France and KLM agreed to a merger plan in which Air France and KLM would become subsidiaries of a holding company called Air France–KLM. Both airlines would retain their own brands, and both Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris and Amsterdam Airport Schiphol would become key hubs.[29] In February 2004, the European Commission and United States Department of Justice approved the proposed merger of the airlines.[30][31] In April 2004, an exchange offer in which KLM shareholders exchanged their KLM shares for Air France shares took place.[32] Since 5 May 2004, Air France–KLM has been listed on the Euronext exchanges in Paris, Amsterdam and New York.[33] In September 2004, the merger was completed by creation of the Air France–KLM holding company.[33] The merger resulted in the world's largest airline group and should have led to an estimated annual cost-saving of between €400 million and €500 million.[34]

It did not appear that KLM's longstanding joint venture with Northwest Airlines—which merged with Delta Air Lines in 2008—was affected by the merger with Air France. KLM and Northwest joined the SkyTeam alliance in September 2004. Also in 2004, senior management came under fire for providing itself with controversial bonuses after the merger with Air France, while 4,500 jobs were lost at KLM. After external pressure, management gave up on these bonuses.[35]

In March 2007, KLM started to use the Amadeus reservation system, along with partner Kenya Airways. After 10 years as president of the airline, Leo van Wijk resigned from his position and was succeeded by Peter Hartman.[36]

2010s

Beginning in September 2010, KLM integrated the passenger division of Martinair into KLM, transferring all personnel and routes. By November 2011, Martinair consisted of only the cargo and maintenance division.[37] In March 2011, KLM and InselAir reached an agreement for mutual cooperation on InselAir destinations, thus expanding its passenger services. Beginning 27 March 2011, KLM passengers could fly to all InselAir destinations through InselAir's hubs in Curacao and Sint Maarten.[38][39] This cooperation was extended to a codeshare agreement in 2012.[40]

On 20 February 2013, KLM announced that Peter Hartman would resign as president and CEO of KLM on 1 July 2013. He was succeeded by Camiel Eurlings. Hartman remained employed by the company until he retired on 1 January 2014.[41] On 15 October 2014, KLM announced that Eurlings, in joint consultation with the supervisory board, had decided to immediately resign as president and CEO. As of this date, he was succeeded by Pieter Elbers.[3]

KLM received the award for "Best Airline Staff Service" in Europe at the World Airline Awards 2013. This award represents the rating for an airline's performance across both airport staff and cabin staff combined.[42] It is the second consecutive year that KLM won this award; in 2012 it was awarded with this title as well.[43]

On 19 June 2012, KLM made the first transatlantic flight fueled partly by sustainable biofuels to Rio de Janeiro. This was the longest distance any aircraft had flown on biofuels.[44]

Corporate affairs and identity

Business trends

Key business and operating results of KLM are shown below.

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenues (€ m) | 8,904 | 9,473 | 9,688 | 9,643 | 9,905 | 9,800 |

| Net Profit (€ m) | 1 | -98 | 133 | 341 | 54 | 519 |

| Number of Passengers (m) | 25.3 | 25.8 | 26.6 | 27.7 | 28.6 | 30.4 |

| Passenger Load Factor (%) | 84.3 | 85.7 | 85.8 | 86.5 | 86.4 | 87.2 |

| Revenue Passenger Kilometres (m) | 84.2 | 86.3 | 89.0 | 91.5 | 93.2 | 97.7 |

| Number of Aircraft (at Year's End) incl. Cargo | 204 | 203 | 206 | 202 | 199 | 203 |

| Number of Employees | 37,169 | 35,787 | 35,662 | 35,685 | 35,488 | 34,363 |

| References | [45][46] | [47][45] | [48][47] | [49][48] | [50][49] | [50] |

Management

As of October 2015, KLM's corporate leader is its president and chief executive officer (CEO) Pieter Elbers, who replaced Camiel Eurlings suddenly on 15 October 2014. The president and CEO is part of the larger Executive Committee, which manages KLM and consists of the statutory managing directors and executive vice-presidents of KLM's business units that are represented in the Executive Committee.[51] The supervision and management of KLM are structured in accordance with the two-tier model; the Board of Managing Directors is supervised by a separate and independent Supervisory Board. The Supervisory Board also supervises the general performance of KLM.[52] The Board of Managing Directors is formed by the four Managing Directors, including the CEO. Nine Supervisory Directors comprise the Supervisory Board.[51]

Head office

KLM's head office is located in Amstelveen,[53] on a 6.5-hectare (16-acre) site near Schiphol Airport. The airline's current headquarters was built between 1968 and 1970.[54] Before the opening of the new headquarters, the airline's head office was on the property of Schiphol Airport in Haarlemmermeer.[55]

Subsidiaries

Companies with a major KLM stake include:[56]

| Company | Type | Principal activities | Incorporated in | Group's equity shareholding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cobalt Ground Solutions | Subsidiary | Ground handling | United Kingdom | 60% |

| Cygnific | Subsidiary | Sales and service | Netherlands | 100% |

| EPCOR | Subsidiary | Maintenance | Netherlands | 100% |

| Kenya Airways | Associate | Airline | Kenya | 27% |

| KLM Asia | Subsidiary | Airline | Taiwan | 100% |

| KLM Catering Services | Subsidiary | Catering services | Netherlands | 100% |

| KLM Cityhopper | Subsidiary | Airline | Netherlands | 100% |

| KLM Cityhopper UK | Subsidiary | Airline | United Kingdom | 100% |

| KLM Equipment Services | Subsidiary | Equipment support | Netherlands | 100% |

| KLM Financial Services | Subsidiary | Financing | Netherlands | 100% |

| KLM Flight Academy | Subsidiary | Flight academy | Netherlands | 100% |

| KLM Health Services | Subsidiary | Health services | Netherlands | 100% |

| KLM UK Engineering | Subsidiary | Engineering and maintenance | United Kingdom | 100% |

| Martinair | Subsidiary | Cargo airline | Netherlands | 100% |

| Schiphol Logistics Park | Joint controlled entity | Logistics | Netherlands | 53% (45% voting right) |

| Transavia | Subsidiary | Airline | Netherlands | 100% |

| Transavia France | Associate | Airline | France | 40% |

Former subsidiaries

Subsidiaries, associates, and joint ventures of KLM in the past include:

| Company | Type | Year of establishment | Year of rejection | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air UK | Associate | 1987 | 1998 | Renamed KLM uk upon obtaining majority stake | [57] |

| Braathens | Joint Venture | 1998 | 2003 | — | [58][59] |

| Buzz | Subsidiary | 2000 | 2003 | Sold to Ryanair | [60][61][62] |

| De Kroonduif | Subsidiary | 1955 | 1963 | Acquired by Garuda Indonesia | [63] |

| KLM alps | Subsidiary | 1998 | 2001 | Franchise agreement with Air Engiadina and Air Alps | [64][65] |

| KLM exel | Subsidiary | 1991 | 2004 | — | [66] |

| KLM Helicopters | Subsidiary | 1965 | 1998 | Sold to Schreiner Airways | [67][68][69] |

| KLM Interinsulair Bedrijf (KLM-IIB) | Subsidiary | 1947 | 1949 | Nationalized and renamed Garuda Indonesia | [70] |

| KLM uk | Subsidiary | 1998 | 2002 | Merged with KLM Cityhopper | [57][71] |

| NetherLines | Subsidiary | 1988 | 1991 | Merged with NLM CityHopper and formed KLM Cityhopper | [72][73] |

| NLM CityHopper | Subsidiary | 1966 | 1991 | Merged with NetherLines and formed KLM Cityhopper | [73][74] |

| High Speed Alliance | Subsidiary | 2007 | 2014 | 5% (10% voting) share before it became NS International | [75] |

KLM also worked closely with ALM Antillean Airlines in the Caribbean in order to provide air service for the Dutch controlled islands in the region with KLM aircraft such as the Douglas DC-8 and McDonnell Douglas DC-9-30 being operated by KLM flight crews on behalf of ALM.[76]

KLM Asia

.jpg)

KLM Asia (Chinese: 荷蘭亞洲航空公司; pinyin: Hélán Yàzhōu Hángkōng Gōngsī) is a wholly KLM-owned subsidiary registered in Taiwan. The airline was established in 1995 to operate flights to Taipei without compromising the traffic rights held by KLM for destinations in the People's Republic of China.[77]

The livery of KLM Asia does not feature Dutch national symbols, such as the flag of the Netherlands, nor KLM's stylised Dutch Crown logo. Instead, it features a special KLM Asia logo. The airline has one Boeing 747-400 aircraft, seven Boeing 777-200ER and two Boeing 777-300ER. KLM Asia initially operated the Amsterdam-Bangkok-Taipei route with a B747-400 Combi or a B747-400 non-combi aircraft. Since March 2012, it has operated the revised Amsterdam-Taipei-Manila route with Boeing 777-200ER/-300ER aircraft. Some aircraft are already painted in the revised KLM Asia livery of 2014.[78]

Branding

Dirk Roosenburg designed the KLM logo at its establishment in 1919; he intertwined the letter K, L, and M, and gave them wings and a crown. The crown was depicted to denote KLM's royal status, which was granted at KLM's establishment.[79] The logo became known as the "vinklogo" in reference to the common chaffinch.[80] The KLM logo was largely redesigned in 1961 by F.H.K. Henrion. The crown, formed by a line, four blue circles and a cross, was retained. In 1991, the logo was further revised by Chris Ludlow of Henrion, Ludlow & Schmidt.[81] In addition to its main logo, KLM displays its alliance status in its branding, including "Worldwide Reliability" with Northwest Airlines (1993–2002) and the SkyTeam alliance (2004–present).[82]

Livery and uniforms

KLM has utilized several major liveries since its founding, with numerous variations on each. Initially many aircraft featured a bare-metal fuselage with a stripe above the windows bearing the phrase "The Flying Dutchman". The rudder was divided into three segments and painted to match the Dutch flag. Later aircraft types sometimes bore a white upper fuselage, and additional detail striping and titling. In the mid-1950s, the livery was changed to feature a split cheatline in two shades of blue on a white upper fuselage, and angled blue stripes on the vertical stabilizer. The tail stripes were later enlarged and made horizontal, and the then-new crown logo was placed in a white circle. The final major variation of this livery saw the vertical stabilizer painted completely white with the crown logo in the center. All versions of this livery had small "KLM Royal Dutch Airlines" titles, first in red, and later in blue.

Since 1971, the KLM livery has primarily featured a bright blue fuselage, with variations on the striping and details. Originally a wide, dark blue cheatline covered the windows, and was separated from the light gray lower fuselage by a thin white stripe. The KLM logo was placed centrally on the white tail and on the front of the fuselage. In December 2002, KLM introduced an updated livery in which the white strip was removed and the dark-blue cheatline was significantly narrowed. The bright blue color was retained and now covers most of the fuselage. The KLM logo was placed more centrally on the fuselage while its position on the tail and the tail design remained the same.[83] In 2014, KLM modified its livery with a swooping cheatline that wraps around the entire forward fuselage. The livery was first introduced on Embraer 190 aircraft.[84]

KLM also has several aircraft painted in special liveries; they include the following:

- PH-BXA, the airline's first 737-800, is painted in the livery introduced on the Lockheed Electra fleet pictured at right.

- PH-BVA, a Boeing 777-300ER, features an orange forward fuselage that fades into the standard blue to commemorate the Netherlands national team's participation in the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro.[85]

- PH-KZU, a Fokker F70, has been applied with a special livery featuring Anthony Fokker, the founder of Fokker, commemorating the airline's long standing history with Fokker aircraft and the phase out of the Fokker 70 aircraft in October 2017.[86]

- Several aircraft bear the silver SkyTeam alliance livery, including PH-BVD (a 777-300ER), PH-BXO (a 737-900), and PH-EZX (a KLM Cityhopper ERJ-190).

In April 2010, KLM introduced new uniforms for its female cabin attendants, ground attendants and pilots at KLM and KLM Cityhopper. The new uniform was designed by Dutch couturier Mart Visser. It retains the KLM blue color that was introduced in 1971 and adds a touch of orange—the national color of the Netherlands.[87]

Marketing slogans

KLM has used several slogans for marketing throughout its operational history:

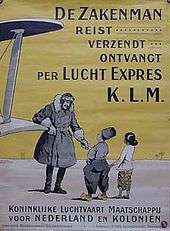

- "The businessman travels, sends, and receives by KLM" (translated from Dutch)[88][89] (1920s)

- "The Flying Dutchman"[88][90]

- "Bridging the World"[88] (1994)

- "The Reliable Airline"[91]

- "KLM, A Journey of Inspiration"[91][92] (2009–present)

Social media

KLM has an extensive presence on social media platforms Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, Instagram, LinkedIn, Google+, and YouTube, and also runs a blog.[93] Customers can make inquiries through these channels. The airline also uses these networks to inform customers of KLM news, marketing campaigns and promotions.

The airline's use of social media platforms to reach customers peaked when the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajökull erupted in April 2010, causing widespread disruption to air traffic. Customers used the social networks to contact the airline, which used them to provide information about the situation.[94] Following the increased use of social media, KLM created a centralized, public social media website named the Social Media Hub in October 2010.[95]

KLM has developed several services based on these social platforms, including:

- Meet & Seat; this service allows passengers to find information about people who will be on the same KLM flight by connecting their Facebook or LinkedIn profiles to the flight. Meet & Seat facilitates contact with fellow travelers who have the same background or interests.[96] By launching Meet & Seat, KLM became the first airline to integrate social networking into its regular flight process.[97]

- Trip Planner; this platform uses Facebook to organize a trip with Facebook friends.[98]

- Twitterbots; KLM operates several Twitterbots, including one to request the current status of a flight and one to request the lowest KLM fares to a destination on a specified date or month.[99]

In June 2013, KLM launched its own 3D strategy game "Aviation Empire" for iOS and Android platforms. The game allows users to experience airline management. Players manage KLM from its establishment until the present; they can by investing in a fleet, build a network with international destinations and develop airports. The game combines the digital world with the real world by enabling the unlocking of airports by GPS check-ins.[100]

Philanthropy

KLM started KLM AirCares, a program that aids underprivileged children in developing countries to which KLM flies, in 1999.[101] The airline collects money and airmiles from passengers. In 2012, new applications for support from the program were suspended because it needed an overhaul.[102]

Destinations

KLM and its partners serve 133 destinations in 70 countries on five continents from their hub at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport.[103][104]

Codeshare agreements

KLM codeshares with the following airlines:[105]

- Adria Airways

- Aer Lingus

- Aeroflot

- Aerolíneas Argentinas

- Aeroméxico

- Air Astana

- Air Europa

- Air France

- Air Malta

- Air Mauritius (begins 30th October 2017)

- Air Serbia

- airBaltic

- Alaska Airlines

- Alitalia

- Bangkok Airways

- Belavia

- Bulgaria Air

- China Airlines

- China Eastern Airlines

- China Southern Airlines

- CityJet

- Copa Airlines

- Croatia Airlines

- Czech Airlines

- Delta Air Lines

- Etihad Airways

- Garuda Indonesia

- Georgian Airways

- Gol Transportes Aéreos

- Insel Air

- Jet Airways

- Kenya Airways

- Korean Air

- Malaysia Airlines

- Oman Air

- Pegasus Airlines

- Saudia

- Sichuan Airlines

- TAAG Angola Airlines

- TAROM

- Transavia

- Ukraine International Airlines

- Vietnam Airlines

- WestJet

- XiamenAir

Fleet

Current fleet

_(2).jpg)

wearing the special Orange Dutch Pride livery

As of February 2017, the KLM fleet (excluding its subsidiaries KLM Cityhopper, Transavia and Martinair) consists of the following aircraft:[106][107]

| KLM Main Line Fleet | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aircraft | In Service | Orders | Passengers[108] | Notes | |||

| C | Y+ | Y | Total | ||||

| Airbus A330-200 | 8 | — | 30 | 35 | 178 | 243 | |

| 18 | 36 | 218 | 272 | ||||

| Airbus A330-300 | 5 | — | 30 | 40 | 222 | 292 | |

| Airbus A350-900 | — | 7 | TBA | Expected in service: 2020 | |||

| Boeing 737-700 | 18 | — | 20 | 6 | 106 | 132 | |

| Boeing 737-800 | 27 | — | 20 | 6 | 150 | 176 | |

| Boeing 737-900 | 5 | — | 28 | 18 | 132 | 178 | |

| Boeing 747-400 | 6 | — | 35 | 36 | 337 | 408 | Expected phase out 2021 |

| Boeing 747-400M | 9 | — | 35 | 36 | 197 | 268 | Combi aircraft version. Expected phase out 2021 |

| Boeing 777-200ER | 15 | — | 34 | 40 | 242 | 316 | |

| Boeing 777-300ER | 13 | 1 | 34 | 40 | 334 | 408 | |

| Boeing 787-9 | 9[109] | 6 | 30 | 48 | 216 | 294 | |

| Boeing 787-10 | — | 6 | TBA | Expected in service: 2020 | |||

| KLM Cargo Fleet | |||||||

| Boeing 747-400ERF | 3 | — | 112,760 kg (248,590 lb) | ||||

| Total | 118 | 20 | |||||

Former fleet

Over the years, KLM has operated the following aircraft types:[110]

| Aircraft | Introduced | Retired |

|---|---|---|

| Airbus A310-200 | 1983 | 1997 |

| Boeing 737-300 | 1986 | 2011 |

| Boeing 737-400 | 1989 | 2011 |

| Boeing 747-200 | 1971 | 2004 |

| Boeing 747-300 | 1983 | 2004 |

| Boeing 767-300ER | 1995 | 2007 |

| Convair 240 | 1948 | 1959 |

| Convair 340 | 1953 | 1964 |

| De Havilland DH.16 | 1920 | 1924 |

| Douglas DC-2 | 1934 | 1946 |

| Douglas DC-3 | 1936 | 1964 |

| Douglas DC-4 | 1946 | 1958 |

| Douglas DC-5 | 1940 | 1941 |

| Douglas DC-6 | 1948 | 1963 |

| Douglas DC-7 | 1953 | 1966 |

| Douglas DC-8 Family[111] | 1960 | 1985 |

| Douglas DC-9-10 / McDonnell Douglas DC-9-30 | 1966 | 1989 |

| Douglas Skymaster C-54 | 1945 | 1959 |

| Fokker F.XXXVI | 1935 | 1939 |

| Fokker F.XXII | 1935 | 1939 |

| Fokker F.XX | 1933 | 1936 |

| Fokker F.XVIII | 1932 | 1946 |

| Fokker F.XII | 1931 | 1936 |

| Fokker F.IX | 1930 | 1936 |

| Fokker F.VIII | 1927 | 1940 |

| Fokker F.VII | 1925 | 1936 |

| Fokker F.III | 1921 | 1930 |

| Fokker F.II | 1920 | 1924 |

| Lockheed L-188 Electra | 1959 | 1969 |

| Lockheed Super Constellation L-1049 | 1953 | 1966 |

| Lockheed Super Electra-14 | 1938 | 1948 |

| McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 | 1972 | 1995 |

| McDonnell Douglas MD-11 | 1993 | 2014 |

| Vickers Viscount | 1957 | 1966 |

Cabin

KLM has three cabin classes for international long-haul routes; World Business Class, Economy Comfort and Economy. Personal screens with audio-video on demand, satellite telephone, SMS, and e-mail services are available in all cabins on all long-haul aircraft . European short-haul and medium-haul flights have Economy seats in the rear cabin, and Economy Comfort and Europe Business in the forward cabin.

World Business Class

World Business Class is KLM's long-haul business class product. Seats in the older World Business Class are 20 inches (51 cm) wide and have a 60-inch (150 cm) pitch.[112] Seats can be reclined into a 170-degree angled flat bed with a length of 75 inches (190 cm). Seats are equipped with a 10.4-inch (26 cm) personal entertainment system with audio and video on demand in the armrest, privacy canopy, massage function and laptop power ports.[113] World Business Class seating is in a 2–2–2 abreast arrangement on all Boeing 777s and on all Airbus A330s, and a 2–2 abreast arrangement on the main deck and upper deck of Boeing 747-400s.[114] All Boeing 777-300ER and Boeing 777-200ER and Boeing 747-400 aircraft have newer World Business Class seats based on the Business Class seats used by Air France. These seats are arranged in a pod-style layout and recline into a 175 degree-angled flat bed.

In March 2013, KLM introduced a new World Business Class seat to the long-haul fleet. Dutch designer Hella Jongerius designed the new cabin and the new flat-bed seat,which will replace both versions of the angled flat seats that are currently offered. The diamond-type seat is manufactured by B/E Aerospace and is installed on Boeing 747-400 and Boeing 777. The new seats are fully flat and offer 17-inch (43 cm)-high definition personal entertainment systems. When fully flat, the bed is about 2 metres (6.6 ft) long. The cabin features a cradle-to-cradle carpet made from old uniforms woven in an intricate pattern, which is combined with new pillows and curtains with a similar design.[115]

A completely new design of Business Class seat was introduced with the launch of KLM's Boeing 787; this aircraft's business class seats are based on the Zodiac Cirrus platform used by Air France. The new seats lie fully-flat, with a 1-2-1 layout so every passenger has direct aisle access, a large side-storage area and 16-inch (41 cm) HD video screen.[116][117] Dutch design group Viktor & Rolf has designed and provides amenity kits to World Business Class passengers. A new design will be introduced each year and the color of the kits will change every six months. The kit contains socks, eye mask, toothbrush, toothpaste, earplugs and Viktor & Rolf lip balm.[118][119][120][121]

Europe Business Class

Europe Business Class is KLM's and KLM Cityhopper's, short-haul business-class product. Europe Business Class seats are 17-inch (43 cm) wide and have an average pitch of 33 inches (84 cm).[112] Middle seats in rows of three are blocked to increase passengers' personal space. Europe Business Class seats feature extra legroom and recline further than regular Economy Class seats. In-seat power is available on all Boeing 737 aircraft.[122] Europe Business Class has no personal entertainment. Seating is arranged 3–3 abreast with the middle seat blocked on the Boeing 737 aircraft, a 3–2 abreast arrangement with the middle seat blocked on the Fokker 70 aircraft, and a 2–2 abreast arrangement on the Embraer 190 aircraft.[114]

Economy Comfort

Economy Comfort is the premium economy product offered on all KLM and KLM Cityhopper flights. Economy Comfort seats on long-haul flights have 4 inches (10 cm) more pitch than Economy Class, a 35–36-inch (89–91 cm) pitch and recline up to 7 inches (18 cm); double the recline of Economy.[123] Economy Comfort seats on short-haul flights have 3.5 inches (8.9 cm) more pitch, totaling 33.5–34.5-inch (85–88 cm), and can recline up to 5 inches (13 cm) (40%) further.[124] Except for the increased pitch and recline, seating and service in Economy Comfort is the same as in Economy Class. Economy Comfort is located in a separate cabin before the Economy Class; passengers can exit the aircraft before Economy passengers.[125]

Economy Comfort seats can be reserved by Economy Class passengers. The service is free for passengers with a full-fare ticket, for Flying Blue Platinum members and for Delta Air Lines SkyMiles Platinum or Diamond members. Discounts apply for Flying Blue Silver or Gold members, SkyTeam Elite Plus members and Delta SkyMiles members.[125]

Economy Class

The Economy Class seats on long-haul flights have a 31-to-32-inch (79–81 cm) pitch and are 17.5 inches (44 cm) wide.[112][123] All seats are equipped with adjustable winged headrests, a 9-inch (23 cm) PTV with AVOD, and a personal handset satellite telephone that can be used with a credit card. Economy Class seats in Airbus A330-300 aircraft are also equipped with in-seat power.[112] The Economy Class seats on short-haul flights have a 30-to-31-inch (76–79 cm) pitch and are 17 inches (43 cm) wide.[112][123] The Economy Class seats on short-haul flights do not feature any personal entertainment. The long-haul Economy Class seating is in a 3–4–3 abreast arrangement on the Boeing 747-400 and Boeing 777-300ER aircraft, a 3–4–3 abreast arrangement on Boeing 777-200ER aircraft, a 3-3-3 abreast arrangement on the Boeing 787-9 aircraft, and a 2–4–2 abreast arrangement on the Airbus A330 aircraft. The short-haul Economy Class seating is in a 3–3 abreast arrangement on the Boeing 737 aircraft, a 3–2 abreast arrangement on the Fokker 70 aircraft and a 2–2 abreast arrangement on the Embraer 190 aircraft.[114] [126]

Services

In-flight entertainment

KLM's in-flight entertainment system is available in all classes on all widebody aircraft; it provides all passengers with Audio/Video on Demand (AVOD). The system includes interactive entertainment including movies, television programs, music, games, and language courses. About 80 movies including recent releases, classics and world cinema are available in several languages. The selection is changed every month.[127] The in-flight entertainment system can be used to send SMS text messages and emails to the ground. Panasonic's 3000i system is installed on all Boeing 747-400, Boeing 777-200ER, and on most of the Airbus A330-200 aircraft.[128] All Airbus A330-300 and Boeing 777-300ER aircraft, and some Airbus A330-200 aircraft are fitted with the Panasonic eX2 in-flight entertainment system.[129]

KLM provides a selection of international newspapers to its passengers on long-haul flights; on short-haul flights they are only offered to Europe Business Class passengers. A selection of international magazines is available for World Business Class passengers on long-haul flights.[130] All passengers are provided with KLM's in-flight magazine, the Holland Herald.[131] On board flights to China, South Korea and Japan, the airline offers in-flight magazines EuroSky (China and Japan), in either Chinese or Japanese, and Wings of Europe (South Korea) in Korean.[132] On 29 May 2013, KLM and Air France launched a pilot scheme to test in-flight Wi-Fi internet access. Each airline equipped one Boeing 777-300ER in its fleet with Wi-Fi, which passengers can use with their Wi-Fi-enabled devices. Wireless service was available after the aircraft reached 20,000 feet (6,100 m) in altitude.[133]

Catering

World Business Class passengers are served a three-course meal. Each year KLM partners with a leading Dutch chef to develop the dishes that are served on board. Passengers in Europe Business Class are served either a cold meal, a hot main course, or a three-course meal depending on the duration of the flight.[134] All chicken served in World and Europe Business Class meets the standards of the Dutch Beter Leven Keurmerk (Better Life Quality Mark).[135] KLM partnered with Dutch designer Marcel Wanders to design the tableware of World and European Business Class.[136]

Economy Class passengers on long-haul flights are served a hot meal and a snack, and second hot meal or breakfast, depending on the duration of the flight. On short-haul flights, passengers are served sandwiches or a choice of sweet or savory snack, depending on the duration and time of the day. If the flight is at least two hours long, "stroopkoekje" cookies are served before descent. Most alcoholic beverages are free of-charge for all passengers. After a successful trial period, KLM introduced à la carte meals in Economy Class on 14 September 2011; Dutch, Japanese, Italian, cold delicacies, and Indonesian meals are offered.[137][138]

Special meals, include children's, vegetarian, medical, and religious meals, can be requested in each class up to 24 or 36 hours before departure.[139] On flights to India, China, South Korea, and Japan, KLM offers authentic Asian meals in all classes.[132] Meals served on KLM flights departing from Amsterdam are provided by KLM Catering Services.[140]

In September 2016, KLM launched world's first in-flight draft beer under the partnership with Heineken. The new service made its premiere this week aboard a flight to Curacao in the airline's World Business Class cabin.[141]

Delft Blue houses

Since the 1950s, KLM presents its World Business Class passengers with a Delft blue, miniature, traditional, Dutch house.[142] These miniatures are reproductions of real Dutch houses and are filled with Dutch genever.[143] Initially the houses were filled with Bols liqueur, which in 1986 was changed for Bols young genever.[144]

In 1952, KLM started to give the houses to its First Class passengers. With the elimination of First Class in 1993, the houses were handed out to all Business Class passengers.[145] The impetus for these houses was a rule aimed at curtailing a previously widespread practice of offering incentives to passengers by limiting the value of gifts given by airlines to 0.75 US cents. KLM did not bill the Delft Blue houses as a gift, but as a last drink on the house, which was served in the house.[145][146]

Every year, a new house is presented on 7 October, the anniversary of KLM's founding in 1919.[143] The number on the last-presented house thus represents the number of years KLM has been in operation. Special edition houses—the Dutch Royal Palace and the 17th century Cheese Weighing House De Waag in Gouda—are offered to special guests, such as VIPs and honeymoon couples.[145]

Ground services

KLM offers various check-in methods to its passengers, who can check in for their flights at self-service check-in kiosks at the airport, via the Internet, or via a mobile telephone or tablet. At destinations where these facilities are not available, check-in is by an airline representative at the counter. Electronic boarding passes can be received on a mobile device while boarding passes can be printed at airport kiosks.[147][148]

Since 4 July 2008 KLM, in cooperation with Amsterdam Airport Schiphol, has been offering self-service baggage drop-off to its passengers. The project started with a trial that included one drop-off point.[149] The number of these points has gradually increased; as of 8 February 2012 there are 12 of them.[150] KLM passengers can now drop off their bags themselves. Before they are allowed to do that they are being checked by a KLM employee.

In November 2012, KLM started a pilot scheme at Amsterdam Airport Schiphol to test self-service boarding. Passengers boarded the aircraft without interference of a gate agent by scanning their boarding passes, which opened a gate. KLM partner airline Air France ran the same pilot at its hub at Paris-Charles de Gaulle Airport. The pilot ran until March 2013, which was followed by an evaluation.[151]

KLM is the first airline to offer self-service transfer kiosks on its European and intercontinental routes for passengers connecting through Amsterdam Airport Schiphol.[152] The kiosks enable connecting passengers to view flight details of connecting flights, to change seat assignments or upgrade to a more comfortable seat. When a passenger misses a connecting flight, details about alternative flights can be viewed on the kiosk and a new boarding pass can be printed. Passengers who are entitled to coupons for a beverage, meal, the use of a telephone, or a travel discount can have these printed at the kiosk.[153]

Bus services and train codeshares

KLM has bus services for customers living in certain cities without flights from KLM, transporting them to airports where they may board KLM flights. It operates buses from Nijmegen railway station and Arnhem Central Station in the Netherlands to Amsterdam Schiphol, and from Ottawa Railway Station to Montreal Dorval Airport in Canada. In addition KLM has codeshares with Thalys and SNCF services so passengers from various French cities may travel to Charles de Gaulle Airport and passengers from Belgium may go to Schiphol (from Antwerp) or Charles de Gaulle (from Brussels).[154]

Flying Blue

Air France-KLM's frequent flyer program, Flying Blue, awards miles based on the distance traveled, ticket fare and class of service. Other airlines that adopted the Flying Blue programme include Air Europa, Garuda Indonesia, Kenya Airways, Aircalin, and TAROM.[155] Miles can also be earned from all other SkyTeam partners.[156] Membership in the program is free.[157] Two types of miles can be earned within the Flying Blue program; Award Miles and Level Miles. Award Miles can be exchanged for rewards and expire after 20 months without flying. Level Miles are used to determine membership level and remain valid until 31 December of each year.[158]

Award Miles can be earned on Flying Blue partner airlines including Alaska Airlines, Air Corsica, Airlinair, Bangkok Airways, Chalair Aviation, Comair, Copa Airlines, Gol Transportes Aéreos, Japan Airlines, Jet Airways, Malaysia Airlines, Qantas, TAAG Angola, Twin Jet, and Ukraine International Airlines, as well as SkyTeam partners.[159][160] Award Miles are redeemable for free tickets, upgrades to a more expensive seating class, extra baggage allowance, and lounge access. They can also be donated to charity through KLM AirCares,[161] or can be spent in the Flying Blue Store.[162]

The Flying Blue programme is divided into four tiers; Ivory, Silver (SkyTeam Elite), Gold (SkyTeam Elite Plus) and Platinum (SkyTeam Elite Plus).[163] The membership tier depends on the number of Level Miles earned and is recalculated each calendar year. Flying Blue privileges are additive by membership tier; higher tiers include all benefits listed for prior tiers. There is an additional fifth tier, Platinum for Life, which can be obtained after 10 consecutive years of Platinum membership. After the Platinum for Life status is obtained, re-qualification is not required.[164] Level Miles can be earned with Air France, KLM, Air Europa, Kenya Airways, TAROM, and other SkyTeam partners.[158] Qualification levels and general benefits with SkyTeam airline partners of the Flying Blue tiers are:[164][165][166][167][168]

Incidents and accidents

The most notable accident involving a KLM aircraft was the 1977 Tenerife airport disaster, which led to 583 fatalities.

Tenerife airport disaster

The Tenerife disaster, which occurred on 27 March 1977, remains the accident with the highest number of airliner passenger fatalities. 583 people died when a KLM Boeing 747-206B attempted to take off without clearance, and collided with a taxiing Pan Am 747-121 at Los Rodeos Airport on the Canary Island of Tenerife, Spain. No one on the KLM 747 survived while 61 of the 396 passengers and crew on the Pan Am aircraft survived. Pilot error from the KLM aircraft was the primary cause. Owing to a communication misunderstanding, the KLM captain thought he had clearance for takeoff.[169][170] Another cause was dense fog, meaning the KLM flight crew was unable to see the Pan Am aircraft on the runway until immediately prior to the collision.[171] The accident had a lasting influence on the industry, particularly in the area of communication. An increased emphasis was placed on using standardized phraseology in air traffic control (ATC) communication by both controllers and pilots alike, thereby reducing the chance for misunderstandings. As part of these changes, the word "takeoff" was removed from general usage, and is only spoken by ATC when actually clearing an aircraft to take off.[172]

Other fatal accidents

1920s–1930s

- On 24 April 1923, Fokker F.III H-NABS departed Lympne for Rotterdam and Amsterdam. The aircraft was not heard from again. It was presumed to have crashed into the sea, killing the pilot and both passengers.[173]

- On 25 June 1925, Fokker F.III H-NABM struck trees and crashed at Locquignol, France while flying too low in poor visibility, killing all four on board.

- On 9 July 1926, Fokker F.VII H-NACC crashed in thick fog near Wolverthem, Belgium, killing both pilots.

- On 22 August 1927, Fokker F.VIII H-NADU crashed near Sevenoaks, England. One crewmember was killed.[174]

- On 14 July 1928, Fokker F.III H-NABR crashed at Waalhaven after striking several ship masts after takeoff; one passenger drowned when the fuselage sank.

- On 20 December 1934, KLM Douglas DC-2 PH-AJU "Uiver" crashed at Rutbah Wells, Iraq, killing all occupants. The aircraft had participated in the Mac Robertson Air Race in October 1934, and won the handicap division. It was on its first flight after return from the race and was en route to the Netherlands East Indies carrying Christmas mail when it crashed.[175]

- On 6 April 1935, KLM Fokker F.XII PH-AFL "Leeuwerik" struck a mountain 15 km (9 mi) from Brilon, Germany after it encountered severe snow and thunderstorms, killing all seven on board.[176]

- On 14 July 1935, KLM Fokker F.XXII PH-AJQ "Kwikstaart" crashed and burned just outside Schiphol after both left side engines failed due to a defect in the fuel system, killing four crew and two passengers. Fourteen occupants survived.[13]

- On 20 July 1935, KLM Douglas DC-2 PH-AKG "Gaai" crashed near the San Bernardino Pass near Pian San Giacomo, killing all three crew and all 10 passengers.[13]

- On 9 December 1936, KLM Douglas DC-2 PH-AKL "Lijster" crashed into a house after taking off from Croydon Airport, London. The accident killed 15 of the 17 people on board the aircraft.

- On 3 April 1937, KLM Douglas DC-3 PH-ALP "Pluvier" was being delivered to KLM when it struck Mount Baldy, Arizona, killing all eight on board.[177]

- On 28 July 1937, KLM Douglas DC-2 PH-ALF "Flamingo" crashed in a field near Beert, Belgium. The crash was caused by an in-flight fire and killed all 15 on board.[178]

- On 6 October 1937, KLM Douglas DC-3 PH-ALS "Specht" crashed on take-off from Talang Betoetoe Airport, killing three crew and one passenger; the co-pilot and seven passengers survived.[179]

- On 14 November 1938, KLM Douglas DC-3 PH-ARY "IJsvogel" struck the ground and crashed near Schiphol Airport for unknown reasons, killing six of 19 on board.[180]

- On 9 December 1938, KLM Lockheed Model 14 Super Electra PH-APE "Ekster" crashed on take-off from Schiphol Airport because of engine failure while on a training flight, killing the four crew.[181]

- On 10 June 1939, KLM Koolhoven F.K.43 "Krekel" stalled and crashed at Vlissingen, killing all three on board.

1940s

- On 28 December 1941, KNILM Douglas DC-3 PK-ALN "Nandoe" (formerly KLM PH-ALN) was destroyed on the ground by Japanese fighters at Medan, North Sumatra, Dutch East Indies, killing all crew members and passengers.

- On 1 June 1943, KLM Douglas DC-3 PH-ALI "Ibis", which had escaped the Dutch occupation and was operating under lease to BOAC, operating BOAC Flight 777, was shot down by eight German Junkers Ju 88 fighters over the Bay of Biscay while on the scheduled Lisbon-Bristol route. All 13 passengers and four KLM crew perished. The aircraft had survived attacks in November 1942 and April 1943.

- On 14 November 1946, a KLM Douglas C-47 crashed at Schiphol Airport during a failed landing in poor weather. All 21 passengers, including the Dutch writer Herman de Man, and the five crew were killed.

- On 26 January 1947, KLM Douglas DC-3 PH-TCR crashed after take-off from Copenhagen, killing all 22 on board, including Prince Gustaf Adolf of Sweden.[182]

- On 20 October 1948, KLM Lockheed L-049 Constellation PH-TEN "Nijmegen" crashed near Prestwick, Scotland, killing all 40 aboard.

- On 23 June 1949, KLM Lockheed L-749 Constellation PH-TER "Roermond", piloted by Hans Plesman—the son of CEO Albert Plesman—crashed into the sea off Bari, killing 33 occupants.[183]

- On 12 July 1949, KLM Lockheed L-749 Constellation PH-TDF "Franeker" crashed into a 674-foot (205 m) hill in Ghatkopar near Bombay, India, killing all 45 aboard. Thirteen of those killed were American news correspondents.[184]

1950s–1970s

- On 2 February 1950, KLM Douglas C-47A PH-TEU crashed in the North Sea 40 mi (64 km) off the Dutch coast due to an apparent in-flight fire, killing all seven on board. The aircraft was operating an Amsterdam-London passenger service.[185]

- On 22 March 1952, Flight 592, a Douglas DC-6 (PH-TBJ "Koningin Juliana") crashed at Frankfurt, killing 45 of the 47 occupants.[186]

- On 23 August 1954, Flight 608, a Douglas DC-6B (PH-DFO, "Willem Bontekoe") crashed between Shannon, Ireland, and Schiphol in the North Sea, 40 kilometres (25 mi) from IJmuiden for reasons unknown. All 21 passengers and crew died.

- On 5 September 1954, Flight 633, a Lockheed Super Constellation, ditched in the River Shannon after takeoff from Shannon Airport. Twenty eight of the 56 people on board (46 passengers and 10 crew) were killed.

- On 14 July 1957, Flight 844, a Lockheed Super Constellation, crashed in the sea near Biak, after takeoff from Mokmer Airport at Biak on its way to Manila. The pilot made a low farewell pass over the island, but the aircraft lost altitude, crashed into the sea and exploded. Nine crew and 49 passengers died; there were 10 survivors.

- On 14 August 1958, Flight 607-E, a Lockheed Super Constellation flying from Amsterdam to New York via Shannon, crashed into the ocean 180 kilometres (110 mi) off the coast of County Galway, Ireland, killing all 99 on board.

- On 12 June 1961, Flight 823, a Lockheed L-188 Electra, crashed on approach to Cairo International Airport due to pilot error, killing 20 of 36 on board.

- On 25 October 1968, KLM Aerocarto Douglas C-47A PH-DAA flew into Tafelberg Mountain, Suriname, following an engine failure while on a survey flight. The aircraft collided with the mountain in cloudy conditions, killing three of the five people on board.[187]

Notable incidents without fatalities

- On 26 October 1921, KLM Fokker F.III (H-NABL) crashed while on approach to Rotterdam from London. The aircraft landed in low visibility, struck the ground and crashed upside down. The pilot, the sole occupant, survived and although the aircraft was written off, it was rebuilt and re-registered H-NABR and returned to service, but was destroyed in a 1928 crash.

- On 17 July 1935, KLM DC-2 (PH-AKM, "Maraboe") crashed near Bushehr, Iran. All occupants were rescued.[188]

- On 2 June 1939, KLM DC-2 (PH-AKN, "Nachtegaal") crashed at Schiphol Airport during a single-engine training flight, killing one person on the ground; all four crew survived. The aircraft was rebuilt and returned to service until it was destroyed in a German air raid on 10 May 1940.

- On 10 May 1940, during the German invasion of the Netherlands, nine KLM aircraft (five DC-2's and four DC-3's) were destroyed in a German air raid at Schiphol Airport by aircraft from KG 4.

- On 15 November 1942, KLM DC-3 (PH-ALI, "Ibis"), which had escaped the Dutch occupation and was operating under lease to BOAC as G-AGBB, was attacked by a Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighter. The aircraft was able to land in Lisbon where repairs were carried out. The port wing, engine nacelle and fuselage were damaged by cannon and machine gun fire.

- On 19 April 1943, KLM DC-3 (PH-ALI, "Ibis") was attacked by six Bf 110 fighters. Captain Koene Dirk Parmentier evaded the attackers by dropping to 50 ft (15 m) above the ocean and then climbing steeply into the clouds. The aircraft again sustained damage to the port aileron, shrapnel to the fuselage and a fuel tank. A new wingtip was flown to Lisbon to complete repairs. Despite these attacks, BOAC continued to fly the Lisbon–Whitchurch route. The aircraft was later destroyed in the crash of Flight 777-A.

- On 6 November 1946, KLM Douglas DC-3 (PH-TBO) crashed near Shere on approach to Croydon Airport after a flight from Amsterdam. All 20 passengers and crew survived the accident.[189][190]

- On 27 December 1947, KLM C-47 (PH-TCV) crashed near Leeuwarden after the left wing struck a church steeple; the aircraft belly-landed and skidded across some ditches which broke off both propellers. All 15 on board survived.

- On 16 June 1948, KLM Douglas DC-4 (PH-TCF, "Friesland") landed short of the runway, bounced and landed hard on the runway at Schiphol Airport due to pilot error. All 27 passengers and crew survived. The pilot had come in too low and too slow.

- On 23 March 1952, KLM Lockheed Constellation (PH-TFF, "Venlo") suffered a propeller failure and subsequent engine fire during landing in Bangkok. All 44 passengers and crew escaped shortly before the fire completely consumed the aircraft. A Thai ground crewman ran into the burning aircraft and returned with an infant who had been left behind.[191]

- On 1 January 1953, KLM C-54 (PH-TDL) force-landed in the desert 17 miles from Dhahran Airport due to fuel exhaustion after the crew diverted twice due to poor visibility. All 66 passengers and crew on board survived.

- On 25 May 1953, KLM Convair 240 (PH-TEI, "Paulus Potter") lost altitude just after takeoff from Schiphol Airport. The aircraft belly-landed on the runway and slid off, crossed a road and came to rest in a field. All 34 passengers and crew survived, however two people who were watching the aircraft died when the aircraft crossed the road.

- On 11 June 1961, KLM Douglas DC-7C (PH-DSN) lost an engine at 17,000 feet over the Atlantic en route to Amsterdam from Windsor Locks; the aircraft landed safely at Prestwick with no casualties to the 81 passengers and crew on board.

- On 25 November 1973, Flight 861 was hijacked over Iraq by Palestinian terrorists. The aircraft took off in Amsterdam and was bound for Tokyo. After several hours it made its final landing in Dubai. The passengers were released earlier in Malta. Everyone survived the hijacking.

- On 4 September 1976, Flight 366, a McDonnell Douglas DC-9-33RC (PH-DNM) flying from Malaga to Amsterdam with an intermediate stop in Nice, was hijacked shortly after takeoff from Nice by Palestinian terrorists. After aborted attempts to land in Tunis, the aircraft landed in Larnaca, Cyprus. After refueling, the hijackers attempted to reach Palestine before the aircraft was turned around by Israeli F4 Phantoms. After returning to Cyprus, the passengers were released unharmed and the hijackers surrendered.[192][193] US

- On 3 June 1983, a McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 (PH-DTE, "Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart") was substantially damaged after landing at Panama City International Airport. During landing, the aircraft veered off the runway into muddy ground. The nose gear collapsed and the airplane sustained damage. After repair the plane was put back into service.[194]

- On 15 December 1989, Flight 867 flew through a volcanic plume causing nearly US$80 million of damage to the brand-new Boeing 747-406M. The plane landed in Anchorage, Alaska, with no reported injuries or fatalities.[195][196]

- On 28 November 2004, Flight 1673, a Boeing 737-400 (PH-BTC), suffered a birdstrike upon rotation from Amsterdam Airport Schiphol. The aircraft continued onwards to Barcelona International Airport, where the nose gear collapsed. No injuries or casualties were reported. The aircraft was written off.

Notable KLM employees

- Jacob Veldhuyzen van Zanten, pilot

- Ingrid de Caluwé

- Bob Hiensch, Flight attendant

- Joop van Werkhoven

- Leo Visser, pilot

- Tommy Stackz, Stunt pilot

- Vladmir Belov, Chief engineer

- Lisa Westerhof, pilot

- King Willem-Alexander, guest pilot[197]

See also

- Air transport in the Netherlands

- List of airports in the Netherlands

- List of companies of the Netherlands

References

- 1 2 "The Flying Dutchman is Forty". FLIGHT International. 76 (2638): 321. 2 October 1959. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- 1 2 "The Netherlands' Aviation Industry – KLM Royal Dutch Airlines". FLIGHT International. 99 (3244): 686. 13 May 1971. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- 1 2 "Pieter Elbers appointed President and CEO of KLM, replacing Camiel Eurlings" (Press release). KLM. 15 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ http://www.airfranceklm.com/sites/default/files/communiques/fy_2016_press_release_en.pdf

- ↑ http://www.airfranceklm.com/sites/default/files/communiques/fy_2016_press_release_en.pdf

- ↑ klm.com - Koninklijke Luchtvaart Maatschappij N.V. retrieved 6 December 2016

- ↑ "Air France: Strikers against reality". The Economist. Paris. 20 September 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ↑ "About KLM — Facts & Figures". KLM. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ↑ Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. "Urban Nebula".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 "Koninklijke Luchtvaart Maatschappij, N.V. History". International Directory of Company Histories. 28. 1999. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 "History". KLM Corporate. KLM. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ↑ "H-NACC". Aviacrash.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 (Dutch) Albert Heijn, ed (1969) KL-50 – logboek van vijftig jaar vliegen. Meijer, Amsterdam.

- ↑ "A Gracious Lady – The Lockheed Constellation". KLM Blog. 21 September 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ "The Six". Air & Space. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ "Civil Aviation – To Succeed Dr. Plesman". FLIGHT International. 65 (2356): 347. 19 March 1954. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Pikula, Sam (Major), The ArmaLite AR-10, Regnum Publications (1998), p. 73

- ↑ "KLM Directors Resign". FLIGHT International. 83 (2809): 45. 10 January 1963. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM's New President". FLIGHT International. 83 (2833): 1010. 27 June 1963. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ "Death of KLM President". FLIGHT International. 87 (2933): 820. 27 May 1965. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ "New KLM President". FLIGHT International. 87 (2937): 1010. 24 June 1965. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ "Aircraft owner's and operator's guide: 747-200/-300" (PDF). Aircraft Commerce.

- ↑ Vischer, Freddy. "The years 1969 – 1978". Tradewind Caribbean Airlines. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ "News Scan – KLM Royal Dutch Airlines". FLIGHT International. 130 (4036): 8. 8 November 1986. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Names New MD". FLIGHT International. 137 (4205): 36. 28 February 1990. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ "People – KLM". FLIGHT International. 151 (4577): 52. 4 June 1997. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Reed, Ted (15 November 2014). "Good Bye MD-11 -- Too Bad Nobody Ever Loved You". Forbes. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "KLM Operates Last MD-11 Passenger Flight" (Press release). KLM. 26 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Air France and KLM get close". The Economist. 6 October 2003. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ "Commission clears merger between Air France and KLM subject to conditions" (Press release). European Commission. 11 February 2004. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ "History – 2004". SkyTeam. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ "Air France exchange offer for all common shares of KLM" (Press release). Air France. 2 April 2004. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- 1 2 "2004–05 Reference Document" (PDF). Air France–KLM Finance. Air France–KLM. 12 July 2005. p. 6. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ "Air France – KLM, A Global Airline Market Leader" (PDF) (Press release). Air France / KLM. 5 May 2004. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM senior managers forgo controversial bonuses".

- ↑ "People: 5 December 2006". Flight International. 5 December 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ "Laatste passagiersvlucht Martinair". Blik op Nieuws.nl. 31 October 2011. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ↑ "InselAir and KLM sign agreement" (Press release). InselAir. 18 March 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ "InselAir to Offer Regional Flights for KLM". Routes Online. 21 March 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ "KLM and InselAir To Initiate Code-Sharing" (Press release). KLM. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ "Camiel Eurlings Appointed KLM President & CEO" (Press release). KLM. 20 February 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "The Best Airline Staff Service in Europe". World Airline Awards. Skytrax. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Royal Dutch Airlines wins award for the 2012 Best Airline Staff Service in Europe". World Airline Awards. Skytrax. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ "Biofuel flight to Rio". Klmtakescare.com. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- 1 2 "KLM:Annual Report 2012" (PDF). KLM. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ↑ "KLM:Annual Report 2011" (PDF). KLM. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- 1 2 "KLM:Annual Report 2013" (PDF). KLM. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- 1 2 "KLM:Annual Report 2014" (PDF). KLM. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- 1 2 "KLM:Annual Report 2015" (PDF). KLM. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- 1 2 "KLM:Annual Report 2016" (PDF). KLM. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- 1 2 "KLM Management". KLM Corporate. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Royal Dutch Airlines Annual Report 2011" (PDF). KLM Corporate. 2011. pp. 41, 42. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Contact – Visiting address". KLM Corporate. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM's New Head Office". FLIGHT International. 93 (3091): 855. 6 June 1968. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM (Konninklijke Luchtvaart Maatschappij NV)". FLIGHT International. 95 (3135): 578. 10 April 1969. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Royal Dutch Airlines Annual Report 2012" (PDF). KLM Corporate. 19 March 2013. p. 16. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Air UK Reunion -History". Air UK Reunion. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM signs Braathens and Northwest deals". FLIGHT International. 152 (4596): 29. 15 October 1997. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "SAS to buy troubled Braathens". Flight International. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM uk's no-frills buzz gets off the ground". Flight International. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "Buzz deal completed". Flight International. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "Ryanair snaps up Buzz and increases 737 order". Flight International. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "Vliegen als vervoer in Nieuw-Guinea" [Flying as transport in New-Guinea]. PACE (in Dutch). Papua Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM's alpine deal". Flight International. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "Air Alps lands in Italian hands". Flight International. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Exel Fleet Details and History". Planespotters.net. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "Newsletter May 1985". Den Helder Airport. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ Schreiner, Arnoud. "1996–2000". Schreiner Aviation Group History. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Helikopters BV". FLIGHT International. 113 (3605): 1137. 22 April 1978. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Interinsulair Bedrijf". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "World Airline Directory – KLM uk". FLIGHT International. 153 (4617): 82. 18 March 1998. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM buys Dutch regional". FLIGHT International. 133 (4108): 7. 9 April 1988. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- 1 2 "World Airline Directory – KLM CityHopper". FLIGHT International. 91 (4260): 139. 27 March 1991. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "World Airline Directory – Nederlandse Luchtvaart Maatschappij (NLM)". FLIGHT International. 91 (3031): 581. 13 April 1967. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.timetableimages.com, July 29, 1968 ALM - Dutch Antillean Airlines system timetable & June 15, 1969 KLM system timetable

- ↑ "KLM History". The KLM Source. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM to repaint seven Boeing 777-200 ERs in KLM Asia livery". World Airline News. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "KLM keeps predicate 'Royal'". KLM. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ van Hoogstraten, Dorine (2005). "Gebouwen voor de luchtvaart" [Buildings for aviation]. Dirk Roosenburg, architect 1887–1962 [Dirk Roosenburg, architect 1887–1962] (in Dutch). Rotterdam: 010 Publishers. p. 137. ISBN 9064505322. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Logo". FamousLogos.net. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Royal Dutch Airlines". Evolution of Brands. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "New Livery For KLM Fleet" (Press release). KLM. 20 December 2002. Archived from the original on 22 December 2002. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Welcomes its Latest Embraer 190 and Modified Livery" (Press release). Amstelveen. 29 April 2014. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ↑ http://news.klm.com/orangepride-klms-unique-orange-aircraft-to-promote-the-netherlands

- ↑ https://blog.klm.com/farewell-to-fokker/

- ↑ "KLM introduces new ladies uniform" (Press release). KLM. 14 April 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 Heiden, H.G. (7 October 1994). "Een goed verwarmde kajuit in de winter" [A well-heated cabin in winter]. Reformatisch Dagblad (in Dutch). p. 17. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ↑ van Weezepoel, Paul. "Dutch Aviation History 1919". Dutch Aviation. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ↑ van Weezepoel, Paul. "Dutch Aviation History 1926". Dutch Aviation. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- 1 2 "Airline Slogans for airlines G – N". The Travel Insider. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ↑ "90th anniversary". Holland Herald. KLM. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ↑ "Where to find KLM on social media sites". KLM. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ van Drimmelen, Jochem. "KLM's social media strategy – Part 1". KLM Blog. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ van Drimmelen, Jochem. "KLM's social media strategy – Part 2". KLM Blog. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Meet & Seat". KLM. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ "With Meet & Seat, KLM integrates social media with air travel" (Press release). KLM. 3 February 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Launches Trip Planner – Plan a trip with friends via Facebook" (Press release). KLM. 31 May 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ van Drimmelen, Jochem. "KLM's social media strategy – Part 4". KLM Blog. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Launches 3D Strategy Game 'Aviation Empire'" (Press release). KLM. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ ""KLM AirCares" KLM Website". Corporate.klm.com. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ↑ "KLM AirCares".

- ↑ "Facts & Figures". KLM Corporate. 18 October 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ "SkyTeam Fact Sheet" (PDF). SkyTeam. p. 5. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ "Profile on KLM Royal Dutch Airlines". CAPA. Centre for Aviation. Archived from the original on 2016-10-30. Retrieved 2016-10-30.

- ↑ - KLM Royal Dutch Airlines retrieved 12 February 2017

- ↑ "KLM Plane Facts" (PDF). KLM. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ↑ klm.com - seating plans retrieved 12 May 2017

- ↑ KLM Ontvangt Negende Boeing 787 Dreamliner Luchtvaartnieuws. Retrieved 20 July 2017

- ↑ KLM fleet Airfleets. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ↑ http://www.airliners.net, photos of KLM DC-8 aircraft

- 1 2 3 4 5 "KLM Fleet Information and Seatmaps". Seatguru. TripAdvisor. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ↑ "Travel classes – World Business Class". KLM. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Seating plans". KLM. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Continues to Invest in Its Customers" (Press release). KLM. 19 March 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "New KLM 787 Business Class seats". Lux-traveller.com. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ "KLM Showcase New 787-9 World Business Class Cabin". The Design Air. 24 July 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Lieberman, Melanie (8 January 2015). "Coolest Airline Amenity Kits". Travel and Leisure. Time Inc. p. 11. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Pillai, Shalu (22 July 2015). "The 7 best first class amenity kits according to Afar". Luxury Launches. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Schlappig, Ben. "Review: KLM Business Class 747-400 Amsterdam To Chicago". One Mile At a Time. Boarding Area. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Best Business Class Amenity Kits in the Skies". The Points Guy. 26 March 2015. pp. Spiegel, Jessica. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Travel classes – Europe Business Class". KLM. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Economy Class seats on intercontinental KLM flights" (PDF). KLM. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ↑ "Economy Class seats on European KLM flights" (PDF). KLM. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- 1 2 "Seat in the Economy Comfort zone". KLM. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ↑ https://www.klm.com/travel/gb_en/prepare_for_travel/on_board/seating_plans/787.htm

- ↑ "Many choices and a personal screen". KLM. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ↑ "Matsushita Avionics Systems Corporation's System 3000 IFE Selected by KLM Royal Dutch Airlines for B777-200ER Fleet" (PDF) (Press release). Panasonic Avionics Corporation. 23 September 2002. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ↑ "Panasonic Avionics Corporation Selected by Air France – KLM to Provide World Class Entertainment on Air France's New B777-300ER" (PDF) (Press release). Panasonic Avionics Corporation. 11 September 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ↑ "Travel classes". KLM. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ↑ "The Holland Herald, our award winning magazine". KLM. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- 1 2 "Asia on board: dining and services". KLM. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ "Air France and KLM launch inflight Wi-Fi". KLM (Press release). 29 May 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ "Dining in Business Class". KLM. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Takes New Steps Towards More Sustainable Catering" (Press release). KLM. 1 October 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ "KLM's World Business Class servies van ontwerper Marcel Wanders" [KLM's World Business Class tableware from designer Marcel Wanders] (Press release) (in Dutch). KLM. 9 November 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ "KLM launches ‘à la carte catering’ pilot" (Press release). KLM. 25 May 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ "KLM Introduces "À La Carte Meals"" (Press release). KLM. 28 July 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ "Special meals on board". KLM. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ "Customers". KLM Catering Services. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ David Gianatasio (6 September 2016). "Heineken, KLM Finally Figured Out How to Serve Freshly Tapped Draught Beer on an Airplane". Adweek. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Zegeling, Mark (2015). Little Kingdom by the Sea: a Celebration of Dutch Cultural Heritage - Secrets of the KLM Houses Revealed. Markmedia & Art. ISBN 9081905627.

- 1 2 "KLM Delft Blue houses". KLM. KLM. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ "House of Bols". Bols. Bols. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 Michaels, Daniel (31 May 2008). "The Ultimate Dutch Status Symbol: House-Shaped Booze Bottles; Jet-Setters Hoard, but Avoid Drinking, KLM's Freebies; The $1,000 Cheese Building". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ "Discover all our houses; About KLM Houses". KLM. KLM. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ "All about checking in". KLM. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "KLM App". KLM. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Amsterdam airport Schiphol and KLM launch innovative self-service baggage drop-off trial" (Press release). KLM. 4 July 2008. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Amsterdam Airport Schiphol: Six new Self-Service Baggage Drop-Off units now in use at Amsterdam Airport Schiphol" (Press release). Schiphol Group. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "KLM test 'self service boarding' op Schiphol en Parijs CDG" [KLM tests 'self service boarding' at Schiphol and Paris CDG]. Luchtvaartnieuws (in Dutch). Reismedia. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ "KLM and Schiphol Airport first to launch European and intercontinental Self Service Transfer Kiosks" (Press release). KLM. 15 December 2006. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Transfer to another flight". KLM. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Travel by bus or rail with a KLM ticket." KLM. Retrieved on October 29, 2016.

- ↑ "All about Flying Blue Miles". FlyingBlue.com. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Earn Miles". FlyingBlue.com. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Levels and benefits". FlyingBlue.com. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- 1 2 "Earn Miles". KLM. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ KLM (May 2015). "KLM Maps - World". Holland Herald. G+J Media. 50 (5): 96, 97. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ↑ "Flying Blue Partners". Flying Blue News. Air France – KLM. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ "AirCares". KLM. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ "Spend Miles". KLM. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ "All about benefits". KLM. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- 1 2 "Platinum benefits with SkyTeam airline partners". KLM. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ "Membership thresholds". KLM. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ "Ivory membership". KLM. Retrieved 28 January 2013.