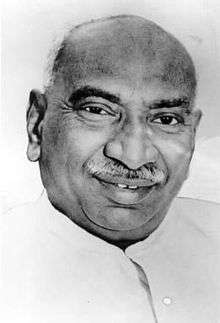

K. Kamaraj

| K. Kamaraj | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd, 4th, 5th Chief Minister of Madras | |

|

In office 1954–1963 | |

| Preceded by | C. Rajagopalachari |

| Succeeded by | M. Bhakthavatsalam |

| Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | |

|

In office 1967–1975 | |

| Preceded by | A. Nesamony |

| Succeeded by | Kumari Ananthan |

| Constituency | Nagercoil |

| Member of Legislative Assembly | |

|

In office 1957–1967 | |

| Preceded by | S. Ramaswamy Naidu |

| Succeeded by | S. Ramaswamy Naidu |

| Constituency | Sattur |

| Member of Legislative Assembly | |

|

In office 1954–1957 | |

| Preceded by | Rathnaswamy and A. J. Arunachala Mudaliar |

| Succeeded by | V. K. Kothandaraman and T. Manavalan |

| Constituency | Gudiyatham |

| Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | |

|

In office 1952–1954 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | S. S. Natarajan |

| Constituency | Srivilliputhur |

| President of Indian National Congress | |

|

In office 1967–1971 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Morarji Desai |

| President of Indian National Congress | |

|

In office 1963–1967 | |

| Preceded by | Neelam Sanjiva Reddy |

| Succeeded by | S. Nijalingappa |

| President of the Madras Provincial Congress Committee | |

|

In office 1946–1952 | |

| Succeeded by | P. Subbarayan |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

15 July 1903 Virudhunagar, Madras Presidency, British India |

| Died |

2 October 1975 (aged 72) Madras (now Chennai, Tamil Nadu), India |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Awards |

|

| Signature |

|

Kumaraswami Kamaraj (b. 15 July 1903[1] – d. 2 October 1975[2]), was a leader of the Indian National Congress (INC), widely acknowledged as the "kingmaker" in Indian politics during the 1960s. He served as INC president for four years between 1964-1967 and was responsible for the elevation of Lal Bahadur Shastri to the position of Prime Minister of India after Indira Gandhi turned down the same at the time of Jawaharlal Nehru's death. Kamaraj was the chief minister of Tamil Nadu during 1954–1963 and a Member of Parliament during 1952–1954 and 1967–1975. He was known for his simplicity and integrity.[1][3]

He was involved in the Indian independence movement.[4] As the president of the INC, he was instrumental in navigating the party after the death of Jawaharlal Nehru. In Tamil Nadu, his home state, he is still remembered for bringing school education to millions of the rural poor by introducing free education and the free Midday Meal Scheme during his tenure as chief minister. He was awarded with India's highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna, posthumously in 1976.[5]

Kamaraj was born on 15 July 1903 to Kumarasamy Nadar and Sivakami at Virudhunagar in Tamil Nadu. His name was originally Kamatchi, but later changed to Kamarajar. His father Kumarasamy was a merchant. In 1907, four years after the birth of Kamaraj, his sister Nagammal was born. At age 5 (1907), Kamaraj was admitted to a traditional school and in 1908 he was admitted to Yenadhi Narayana Vidhya Salai. In 1909 Kamaraj was admitted in Virudupatti High School. Kamaraj's father died when he was six years old and his mother was forced to support her family. In 1914 Kamaraj dropped out of school to support his family.[6]

Politics

He worked in his uncle's provision shop and during this time he started joining processions and attending public meetings about the Indian Home Rule Movement. Kamaraj developed an interest in prevailing political conditions by reading newspapers daily.[7] The Jallianwala Bagh massacre was the decisive turning point in his life, and at this point he decided his aim was to fight for national freedom and to bring an end to foreign rule.[8][9] In 1920, at the age of 18, he became active as a political worker and joined Congress as a full-time worker.[9] In 1921 Kamaraj was organising public meetings at Virudhunagar for Congress leaders. He was eager to meet Gandhi, and when Gandhi visited Madurai on 21 September 1921 Kamaraj attended Gandhi's public meeting and met him for the first time in person. He visited villages carrying Congress propaganda.[10]

In 1922 Congress was boycotting the visit of the Prince of Wales as part of the Non-Cooperation Movement. He came to Madras and took part in this event.[11] He participated in the famous Vaikom Satyagraha led by Narayana Guru against the atrocities of the higher caste Hindus against the Harijans.[12] In 1923–25 Kamaraj participated in the Nagpur Flag Satyagraha.[13] In 1927, Kamaraj started the Sword Satyagraha in Madras and was chosen to lead the Neil Statue Satyagraha, but this was given up later in view of the Simon Commission boycott.[14] Kamaraj led almost all the agitation and demonstration against British rule.[15]

Kamaraj was first jailed in June 1930 for two years in Alipore Jail, Calcutta, for participation in the "Salt Satyagraha" led by Rajagopalachari at Vedaranyam; he was released early in 1931 in consequence of the Gandhi-Irwin Pact before he could serve his full term of imprisonment. In 1932, Section 144 was imposed in Madras prohibiting the holding of meetings and organisation of processions against the arrest of Gandhi in Bombay. In Virdhunagar, under Kamaraj's leadership, processions and demonstrations happened every day. Kamaraj was arrested again in January 1932 and sentenced to one year's imprisonment.[16] In 1933 Kamaraj was falsely implicated in the Virudhunagar bomb case. Varadarajulu Naidu and George Joseph argued on Kamaraj's behalf and proved the charges to be baseless.[17] At the age of 34, Kamaraj entered the Assembly winning the Sattur seat in the 1937 election.

Kamaraj was conducting a vigorous campaign throughout the state asking people not to contribute to war funds when Sir Arthur Hope, the Madras Governor, was collecting contributions to fund for the Second World War. In December 1940 he was arrested again at Guntur, under the Defence of India rules for speeches opposing contributions to the war fund, and sent to Vellore Central Prison while he was on his way to Wardha to get Gandhi's approval for a list of Satyagrahis. While in jail, he was elected as Municipal Councillor of Virudhunagar. He was released nine months later in November 1941 and resigned from this post as he thought he had greater responsibility for the nation. [18][19] His principle was "One should not accept any post to which one could not do full justice".

In 1942, Kamaraj attended the All-India Congress Committee in Bombay and returned to spread propaganda material for the Quit India Movement. The police issued orders to all the leaders who attended this Bombay session. Kamaraj did not want to get arrested before he took the message to all district and local leaders. He decided not to go to Madras and decided to cut short his trip; he saw a large number of policemen waiting for the arrest of Congress leaders in Arakonam but managed to escape from the police and went to Ranipet, Tanjore, Trichy and Madurai to inform local leaders about the programme. He reached Virdhunagar after finishing his work and sent a message to the local police that he was ready to be arrested. He was arrested in August 1942. He was under detention for three years and was released in June 1945. This was his last prison term.[12][18][20] Kamaraj was imprisoned six times by the British for his pro-Independence activities, accumulating more than 3,000 days in jail.[21]

Chief Minister

On 13 April 1954, Kamaraj became the Chief Minister of Madras Province. To everyone's surprise, Kamaraj nominated C. Subramaniam and M. Bhakthavatsalam, who had contested his leadership, to the newly formed cabinet.

As Chief Minister, Kamaraj removed the family vocation based Hereditary Education Policy introduced by Rajaji. The State made immense strides in education and trade. New schools were opened, so that poor rural students had to walk no more than three kilometers to their nearest school. Better facilities were added to existing ones. No village remained without a primary school and no panchayat without a high school. Kamaraj strove to eradicate illiteracy by introducing free and compulsory education up to the eleventh standard. He introduced the Midday Meal Scheme to provide at least one meal per day to the lakhs of poor school children ((The Mid-day Meal Scheme, was first introduced in 1920 by the Madras Corporation with the approval of the legislative council, as a breakfast scheme in a corporation school at Thousand Lights, Madras for the first time in the world)) Later it was expanded to four more schools. This was the precursor to the free noon meal schemes introduced by K. Kamaraj in 1960's and expanded by M. G. Ramachandran in the 1980s.. He introduced free school uniforms to weed out caste, creed and class distinctions among young minds.

During the British regime the education rate was only 7 per cent. But after Kamaraj's reforms it reached 37% . Apart from increasing the number of schools, steps were taken to improve standards of education. To improve standards, the number of working days was increased from 180 to 200; unnecessary holidays were reduced; and syllabuses were prepared to give opportunity to various abilities. Kamaraj and Bishnuram Medhi (Governor) took efforts to establish IIT Madras in 1959.

Major irrigation schemes were planned in Kamaraj's period. Dams and irrigation canals were built across higher Bhavani, Mani Muthar, Aarani, Vaigai, Amaravathi, Sathanur, Krishnagiri, Pullambadi, Parambikulam and Neyyaru among others. The Lower Bhavani Dam in Erode district brought 207,000 acres (840 km2) of land under cultivation. 45,000 acres (180 km2) of land benefited from canals constructed from the Mettur Dam. The Vaigai and Sathanur systems facilitated cultivation across thousands of acres of lands in Madurai and North Arcot districts respectively. Rs 30 crores were planned to be spent for Parambikulam River scheme, and 150 lakhs of acres of lands were brought under cultivation; one third of this (i.e. 56 lakhs of acres of land) received a permanent irrigation facility. In 1957–61 1,628 tanks were de-silted under the Small Irrigation Scheme, and 2,000 wells were dug with outlets. Long term loans with 25% subsidy were given to farmers. In addition farmers who had dry lands were given oil engines and electric pump sets on an installment basis.

Industries with huge investments in crores of Rupees were started in his period: Neyveli Lignite Corporation, BHEL at Trichy, Manali Oil Refinery, Hindustan raw photo film factory at Ooty, surgical instruments factory at Chennai, and a railway coach factory at Chennai were established. Industries such as paper, sugar, chemicals and cement took off during the period.

First Cabinet

Kamaraj's council of ministers during his first tenure as Chief Minister (13 April 1954 – 31 March 1957):[22]

| Minister | Portfolios |

|---|---|

| K. Kamaraj | Chief Minister, Public and Police in the Home Department |

| M. Bhaktavatsalam | Agriculture, Forests, Fisheries, Cinchona, Rural Welfare, Community Projects, National Extension Scheme, Women’s Welfare, Industries and Labour, Animal Husbandry and Veterinary |

| C. Subramaniam | Finance, Food, Education, Elections and Information, Publicity and Law (Courts and Prisons) |

| A. B. Shetty | Medical and Public Health, Co-operation, Housing, Ex-servicemen. |

| M. A. Manickavelu Naicker | Land Revenue, Commercial Taxes, Rural Development |

| Shanmugha Rajeswara Sethupathi | Public Works, Accommodation Control, Engineering Colleges, Stationery and Printing including establishment questions of the Stationery Department and the Government Press |

| B. Parameswaran | Transport, Harijan Uplift, Hindu Religious Endowments, Registration, Prohibition |

| S. S. Ramasami Padayachi | Local Administration |

- Changes

- Following the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, A. B. Shetty quit the Ministry on 1 March 1956 and his portfolio was shared between the other ministers.

Second Cabinet

Kamaraj's council of ministers during kamarajars second tenure as Chief Minister (1 April 1957 – 1 March 1962):[23]

| Minister | Portfolios |

|---|---|

| K. Kamaraj | Chief Minister, Public Planning and Development (including Local Development Works, Women's Welfare, Community Projects and Rural Welfare), National Extension Scheme |

| M. Bhaktavatsalam | Home |

| C. Subramaniam | Finance |

| R. Venkataraman | Industries |

| M. A. Manickavelu Naicker | Revenue |

| P. Kakkan | Works |

| V. Ramaiah | Electricity |

| Lourdhammal Simon | Local Administration |

Third Cabinet

Kamaraj's council of ministers during his third tenure as Chief Minister (3 March 1962 – 2 October 1963):[23][24][25]

| Minister | Portfolios |

|---|---|

| K. Kamaraj | Chief Minister, Public Planning and Development (including Local Development Works, Women's Welfare, Community Projects and Rural Welfare), National Extension Scheme |

| M. Bhaktavatsalam | Finance and Education |

| Jothi Venkatachalam | Public Health |

| R. Venkataraman | Revenue |

| S. M. Abdul Majid | Local Administration |

| N. Nallasenapathi Sarkarai Mandradiar | Cooperation, Forests |

| G. Bhuvaraghan | Publicity and Information |

Kamaraj Plan

Kamaraj remained Chief Minister for three consecutive terms, winning elections in 1957 and 1962. Kamaraj noticed that the Congress party was slowly losing its vigour.

On Gandhi Jayanti day, 2 October 1963, he resigned from the Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Post. He proposed that all senior Congress leaders should resign from their posts and devote all their energy to the re-vitalization of the Congress.

In 1963 he suggested to Nehru that senior Congress leaders should leave ministerial posts to take up organisational work. This suggestion came to be known as the Kamaraj Plan, which was designed primarily to dispel from the minds of Congressmen the lure of power, creating in its place a dedicated attachment to the objectives and policies of the organisation. Six Union Ministers and six Chief Ministers including Lal Bahadur Shastri, Jagjivan Ram, Morarji Desai, Biju Patnaik and S.K. Patil followed suit and resigned from their posts. Impressed by Kamaraj's achievements and acumen, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru felt that his services were needed more at the national level. In a swift move he brought Kamaraj to Delhi as the President of the Indian National Congress. Nehru realized that in addition to wide learning and vision, Kamaraj possessed enormous common sense and pragmatism. Kamaraj was elected President, Indian National Congress, on 9 October 1963.[26]

National politics

After Nehru's death in 1964, Kamaraj successfully navigated the party through turbulent times. As president of the INC, he refused to become the next prime minister himself and was instrumental in bringing to power two Prime Ministers, Lal Bahadur Shastri in 1964 and Nehru's daughter Indira Gandhi in 1966.[27] For this role, he was widely acclaimed as the "kingmaker" during the 1960s.

When the Congress split in 1969, Kamaraj became the leader of the Indian National Congress (Organisation) (INC(O)) in Tamil Nadu. The party failed poorly in the 1971 elections amid allegations of fraud by the opposition parties. He remained as the leader of INC(O) till his death in 1975.[28][29]

Electoral history

| Year | Post | Constituency | Party | Opponent | Election | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1937 | MLA | Sattur | INC | Unopposed | 1937 elections | Won |

| 1946 | MLA | Sattur-Aruppukottai | INC | Unopposed | 1946 elections | Won |

| 1952 | MP | Srivilliputtur | INC | G. D. Naidu | Indian General Elections, 1951 | Won |

| 1954 | MLA | Gudiyatham | INC | V. K. Kothandaraman | By Election | Won |

| 1957 | MLA | Sattur | INC | Jayarama Reddiar | Madras legislative assembly election, 1957 | Won |

| 1962 | MLA | Sattur | INC | P. Ramamoorthy | Madras legislative assembly election, 1962 | Won |

| 1967 | MLA | Virudhunagar | INC | P. Seenivasan | Tamil Nadu state assembly election, 1967 | Lost |

| 1969 | MP | Nagercoil | INC | M. Mathias | By Election | Won |

| 1971 | MP | Nagercoil | INC(O) | M. C. Balan | Indian General Elections, 1971 | Won |

Death

Kamaraj died at his home, on Gandhi Jayanti day (2 October 1975), which was also the 12th anniversary of his resignation. He was aged 72 and died in his sleep.

Legacy

Kamaraj was awarded India's highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna, posthumously in 1976. He is widely acknowledged as "Kalvi Thanthai" (Father of Education) in Tamil Nadu. The domestic terminal of the Chennai airport is named "Kamaraj Terminal". Chennai's beach road is named "Kamarajar Salai", Bangalore's North Parade Road and Parliament road in New Delhi as "K. Kamaraj Road" and the Madurai Kamaraj University in his honour.[3][30]

Popular culture

In 2004 a Tamil-language film titled Kamaraj was made based on the life history of Kamaraj. The English version of the film was released on DVD in 2007.

References

- 1 2 Revised edition of book on Kamaraj to be launched Archived 10 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine., The Hindu, 8 July 2009

- ↑ Crusading Congressman, Frontline Magazine Archived 15 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine., hinduonnet.com. 15–28 September 2001

- 1 2 He raised the bar with simplicity, The Hindu 16 July 2008 Archived 10 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The commonsense politician, Frontline Magazine, 17–30 August 2002 Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Padma Awards Directory (1954–2007)" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ↑ Kapur, Raghu Pati (1966). Kamaraj, the iron man. Deepak Associates. p. 12. Archived from the original on 16 November 2014.

- ↑ Kandaswamy, P. (2001). The Political Career of K. Kamaraj. Concept Publishing Company. p. 23. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017.

- ↑ Kandaswamy, P. (2001). The Political Career of K. Kamaraj. Concept Publishing Company. p. 24. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017.

- 1 2 Freedom Movement In Madras Presidency With Special Reference To The Role Of Kamaraj (1920–1945), Page 1

- ↑ Early Life of K. Kamaraj. p. 25.

- ↑ Freedom Movement In Madras Presidency With Special Reference To The Role Of Kamaraj (1920–1945), Page 2

- 1 2 Bhatnagar, R. K. "Tributes To Kamaraj". Asian Tribune. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ↑ K.Kamaraj Archived 7 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kandaswamy, P. (2001). The Political Career of K. Kamaraj. Concept Publishing Company. p. 30. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017.

- ↑ Remembering Our Leaders. p. 145. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017.

- ↑ Freedom Movement In Madras Presidency With Special Reference To The Role Of Kamaraj (1920–1945), Page 3

- ↑ George Joseph, a true champion of subaltern Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Remembering Our Leaders. p. 146. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Bharat Ratnas. p. 88. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Bharat Ratnas. p. 89. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014.

- ↑ Stepan, Alfred; Linz, Juan J.; Yadav, Yogendra (2011). Crafting State-Nations: India and Other Multinational Democracies. JHU Press. p. 124. ISBN 9780801897238. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017.

- ↑ A Review of the Madras Legislative Assembly (1952–1957) Archived 17 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Kandaswamy, P. (2001). The Political Career of K. Kamaraj. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 62–64. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017.

- ↑ The Madras Legislative Assembly, Third Assembly I Session Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The Madras Legislative Assembly, Third Assembly II Session Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Archived 18 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Will Mamata Banerjee's Hindi handicap hurt her ambition to be prime minister?". Archived from the original on 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam, ed. India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 164.

- ↑ juh

- ↑ Man of the people Archived 6 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine., The Tribune, 4 October 1975

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to K. Kamaraj. |