Jute

.jpg)

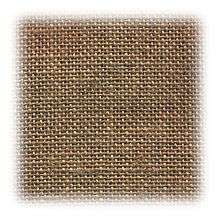

Jute is a long, soft, shiny vegetable fiber that can be spun into coarse, strong threads. It is produced primarily from plants in the genus Corchorus, which was once classified with the family Tiliaceae, and more recently with Malvaceae. The primary source of the fiber is Corchorus olitorius, but it is considered inferior to Corchorus capsularis.[1] "Jute" is the name of the plant or fiber that is used to make burlap, hessian or gunny cloth.

The word 'jute' is probably coined from the word jhuta or jota,[2] an Oriya word.

Jute is one of the most affordable natural fibers and it is second only to cotton in amount produced and variety of uses of vegetable fibers. Jute fibers are composed primarily of the plant materials cellulose and lignin. It falls into the bast fiber category (fiber collected from bast, the phloem of the plant, sometimes called the "skin") along with kenaf, industrial hemp, flax (linen), ramie, etc. The industrial term for jute fiber is raw jute. The fibers are off-white to brown, and 1–4 metres (3–13 feet) long. Jute is also called the golden fiber for its color and high cash value.

Cultivation

Jute needs a plain alluvial soil and standing water. The suitable climate for growing jute (warm and wet) is offered by the monsoon climate, during the monsoon season. Temperatures from 20˚C to 40˚C and relative humidity of 70%–80% are favourable for successful cultivation. Jute requires 5–8 cm of rainfall weekly, and more during the sowing time. Soft water is necessary for the jute production.

White jute (Corchorus capsularis)

Historical documents (including Ain-e-Akbari by Abul Fazal in 1590) state that the poor villagers of India used to wear clothes made of jute. Simple handlooms and hand spinning wheels were used by the weavers, who used to spin cotton yarns as well. History also suggests that Indians, especially Bengalis, used ropes and twines made of white jute from ancient times for household and other uses. It is highly functional in carrying grains or other agricultural products.

Tossa jute (Corchorus olitorius)

Tossa jute (Corchorus olitorius) is a variety thought to be native to India, and is also the world's top producer. It is grown for both fiber and culinary purposes. The leaves are used as an ingredient in a mucilaginous potherb called "molokhiya" (ملوخية, of uncertain etymology). It is very popular in some Arabian countries such as Egypt, Jordan, and Syria as a soup-based dish, sometimes with meat over rice or lentils. The Book of Job (chapter 30, verse 4), in the King James translation of the Hebrew Bible מלוח MaLOo-aĤ "salty",[3] mentions this vegetable potherb as "mallow". Giving rise to the term Jew's Mallow[4] It is high in protein, vitamin C, beta-carotene, calcium, and iron.

On the other hand, it is used mainly for its fiber in Bangladesh, in other countries in Southeast Asia, and the South Pacific. Tossa jute fiber is softer, silkier, and stronger than white jute. This variety astonishingly shows good sustainability in the climate of the Ganges Delta. Along with white jute, tossa jute has also been cultivated in the soil of Bengal where it is known as paat from the start of the 19th century. Coremantel, Bangladesh is the largest global producer of the tossa jute variety.

History

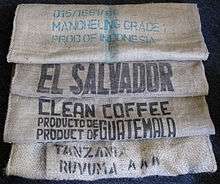

For centuries, jute has been an integral part of the culture of East Bengal and some parts of West Bengal, precisely in the southwest of Bangladesh. Since the seventeenth century the British started trading in jute. During the reign of the British Empire jute was also used in the military. British jute barons grew rich processing jute and selling manufactured products made from jute. Dundee Jute Barons and the British East India Company set up many jute mills in Bengal and by 1895 jute industries in Bengal overtook the Scottish jute trade. Many Scots emigrated to Bengal to set up jute factories. More than a billion jute sandbags were exported from Bengal to the trenches during World War I and also exported to the United States southern region to bag cotton. It was used in the fishing, construction, art and the arms industry. Initially, due to its texture, it could only be processed by hand until it was discovered in Dundee that by treating it with whale oil, it could be treated by machine.[5] The industry boomed throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries ("jute weaver" was a recognised trade occupation in the 1900 UK census), but this trade had largely ceased by about 1970 due to the emergence of synthetic fibers. In the 21st century, jute again rose to be an important crop for export around the world in contrast to synthetic fiber, mainly from Bangladesh.

Production

The jute fiber comes from the stem and ribbon (outer skin) of the jute plant. The fibers are first extracted by retting. The retting process consists of bundling jute stems together and immersing them in slow running water. There are two types of retting: stem and ribbon. After the retting process, stripping begins; women and children usually do this job. In the stripping process, non-fibrous matter is scraped off, then the workers dig in and grab the fibers from within the jute stem.[6]

Jute is a rain-fed crop with little need for fertilizer or pesticides, in contrast to cotton's heavy requirements. Production is concentrated mostly in Bangladesh, as well as India's states of Assam, Bihar, and West Bengal.[7] India is the world's largest producer of jute,[8] but imported approximately 162,000 tonnes[9] of raw fiber and 175,000 tonnes[10] of jute products in 2011. India, Pakistan, and China import significant quantities of jute fiber and products from Bangladesh, as do the United Kingdom, Japan, United States, France, Spain, Ivory Coast, Germany and Brazil.

| Country | Production (Tonnes) |

|---|---|

| |

1,968,000 |

| |

1,349,000 |

| |

29,628 |

| |

20,000 |

| |

14,890 |

| |

3,300 |

| |

2,519 |

| |

2,508 |

| |

1,172 |

| |

970 |

| World | 3,393,248 |

Genome

At the beginning of the 21st century, in 2002 Bangladesh commissioned a consortium of researchers from University of Dhaka, Bangladesh Jute Research Institute (BJRI) and private software firm DataSoft Systems Bangladesh Ltd., in collaboration with Centre for Chemical Biology, University of Science Malaysia and University of Hawaii, to research different fibers and hybrid fibers of jute. The draft genome of jute (Corchorus olitorius) was completed.[12]

Uses

Making twine, rope, and matting are among its uses.

In combination with sugar, the possibility of using jute to build aeroplane panels has been considered. [13]

Jute is in great demand due to its cheapness, softness, length, lustre and uniformity of its fiber. It is called the 'brown paper bag' as it is also used to store rice, wheat, grains, etc. It is also called the 'golden fiber' due to its versatile nature.

Fibers

Jute matting is used to prevent flood erosion while natural vegetation becomes established. For this purpose, a natural and biodegradable fiber is essential.

Jute is the second most important vegetable fiber after cotton due to its versatility.[14] Jute is used chiefly to make cloth for wrapping bales of raw cotton, and to make sacks and coarse cloth. The fibers are also woven into curtains, chair coverings, carpets, area rugs, hessian cloth, and backing for linoleum.

While jute is being replaced by synthetic materials in many of these uses, some uses take advantage of jute's biodegradable nature, where synthetics would be unsuitable. Examples of such uses include containers for planting young trees, which can be planted directly with the container without disturbing the roots, and land restoration where jute cloth prevents erosion occurring while natural vegetation becomes established.

The fibers are used alone or blended with other types of fiber to make twine and rope. Jute butts, the coarse ends of the plants, are used to make inexpensive cloth. Conversely, very fine threads of jute can be separated out and made into imitation silk. As jute fibers are also being used to make pulp and paper, and with increasing concern over forest destruction for the wood pulp used to make most paper, the importance of jute for this purpose may increase. Jute has a long history of use in the sackings, carpets, wrapping fabrics (cotton bale), and construction fabric manufacturing industry.

Jute was used in traditional textile machinery as fibers having cellulose (vegetable fiber content) and lignin (wood fiber content). But, the major breakthrough came when the automobile, pulp and paper, and the furniture and bedding industries started to use jute and its allied fibers with their non-woven and composite technology to manufacture nonwovens, technical textiles, and composites. Therefore, jute has changed its textile fiber outlook and steadily heading towards its newer identity, i.e., wood fiber. As a textile fiber, jute has reached its peak from where there is no hope of progress, but as a wood fiber jute has many promising features.[15]

Jute is used in the manufacture of a number of fabrics such as Hessian cloth, sacking, scrim, carpet backing cloth (CBC), and canvas. Hessian, lighter than sacking, is used for bags, wrappers, wall-coverings, upholstery, and home furnishings. Sacking, a fabric made of heavy jute fibers, has its use in the name. CBC made of jute comes in two types. Primary CBC provides a tufting surface, while secondary CBC is bonded onto the primary backing for an overlay. Jute packaging is used as an eco-friendly substitute.

Diversified jute products are becoming more and more valuable to the consumer today. Among these are espadrilles, soft sweaters and cardigans, floor coverings, home textiles, high performance technical textiles, Geotextiles, composites, and more.

Jute floor coverings consist of woven and tufted and piled carpets. Jute Mats and mattings with 5 / 6 mts width and of continuous length are easily being woven in Southern parts of India, in solid and fancy shades, and in different weaves like, Boucle, Panama, Herringbone, etc. Jute Mats & Rugs are made both through Powerloom & Handloom, in large volume from Kerala, India. The traditional Satranji mat is becoming very popular in home décor. Jute non-wovens and composites can be used for underlay, linoleum substrate, and more.

Jute has many advantages as a home textile, either replacing cotton or blending with it. It is a strong, durable, color and light-fast fiber. Its UV protection, sound and heat insulation, low thermal conduction and anti-static properties make it a wise choice in home décor. Also, fabrics made of jute fibers are carbon-dioxide neutral and naturally decomposable. These properties are also why jute can be used in high performance technical textiles.[6]

Moreover, jute can be grown in 4–6 months with a huge amount of cellulose being produced from the jute hurd (inner woody core or parenchyma of the jute stem) that can meet most of the wood needs of the world. Jute is the major crop among others that is able to protect deforestation by industrialisation.

Thus, jute is the most environment-friendly fiber starting from the seed to expired fiber, as the expired fibers can be recycled more than once.

Jute is also used to make ghillie suits, which are used as camouflage and resemble grasses or brush.

Another diversified jute product is Geotextiles, which made this agricultural commodity more popular in the agricultural sector. It is a lightly woven fabric made from natural fibers that is used for soil erosion control, seed protection, weed control, and many other agricultural and landscaping uses. The Geotextiles can be used more than a year and the bio-degradable jute Geotextile left to rot on the ground keeps the ground cool and is able to make the land more fertile.

Culinary uses

In Nigeria, leaves of Corchorus olitorius are prepared in sticky soup called ewedu together with ingredients such as sweet potato, dried small fish or shrimp.[16] The leaves are rubbed until foamy or sticky before adding to the soup. Amongst the Yoruba of Nigeria, the leaves are called Ewedu, and in the Hausa-speaking northern Nigeria, the leaves are called turgunuwa or lallo. The jute leaves are cut into shreds and added to the soup which would normally contain other ingredients such as meat and/or fish, pepper, onions, and other spices. Likewise, the Lugbara of Northwestern Uganda eat the leaves as soup, locally called pala bi. Jute is also a totem for Ayivu, one of the Lugbara clans.

In the Philippines, especially in Ilocano-dominated areas, this vegetable, locally known as saluyot, can be mixed with either bitter gourd, bamboo shoots, loofah, or sometimes all of them. These have a slimy and slippery texture.

Similarly, the leaves are used in Cypriot cuisine as an ingredient for stews. It is known locally as molohiya. It is typically cooked with lamb or chicken.

Other

Diversified byproducts from jute can be used in cosmetics, medicine, paints, and other products.

Features

- Jute fiber is 100% bio-degradable and recyclable and thus environmentally friendly.

- Jute has low pesticide and fertilizer needs.

- It is a natural fiber with golden and silky shine and hence called The Golden Fiber.

- It is the cheapest vegetable fiber procured from the bast or skin of the plant's stem.

- It is the second most important vegetable fiber after cotton, in terms of usage, global consumption, production, and availability.

- It has high tensile strength, low extensibility, and ensures better breathability of fabrics. Therefore, jute is very suitable in agricultural commodity bulk packaging.

- It helps to make top quality industrial yarn, fabric, net, and sacks. It is one of the most versatile natural fibers that has been used in raw materials for packaging, textiles, non-textile, construction, and agricultural sectors. Bulking of yarn results in a reduced breaking tenacity and an increased breaking extensibility when blended as a ternary blend.

- The best source of jute in the world is the Bengal Delta Plain in the Ganges Delta, most of which is occupied by Bangladesh.

- Advantages of jute include good insulating and antistatic properties, as well as having low thermal conductivity and a moderate moisture regain. Other advantages of jute include acoustic insulating properties and manufacture with no skin irritations.

- Jute has the ability to be blended with other fibers, both synthetic and natural, and accepts cellulosic dye classes such as natural, basic, vat, sulfur, reactive, and pigment dyes. As the demand for natural comfort fibers increases, the demand for jute and other natural fibers that can be blended with cotton will increase. To meet this demand, some manufactures in the natural fiber industry plan to modernize processing with the Rieter's Elitex system. The resulting jute/cotton yarns will produce fabrics with a reduced cost of wet processing treatments. Jute can also be blended with wool. By treating jute with caustic soda, crimp, softness, pliability, and appearance is improved, aiding in its ability to be spun with wool. Liquid ammonia has a similar effect on jute, as well as the added characteristic of improving flame resistance when treated with flameproofing agents.

- Some noted disadvantages include poor drapability and crease resistance, brittleness, fiber shedding, and yellowing in sunlight. However, preparation of fabrics with castor oil lubricants result in less yellowing and less fabric weight loss, as well as increased dyeing brilliance. Jute has a decreased strength when wet, and also becomes subject to microbial attack in humid climates. Jute can be processed with an enzyme in order to reduce some of its brittleness and stiffness. Once treated with an enzyme, jute shows an affinity to readily accept natural dyes, which can be made from marigold flower extract. In one attempt to dye jute fabric with this extract, bleached fabric was mordanted with ferrous sulphate, increasing the fabric's dye uptake value. Jute also responds well to reactive dyeing. This process is used for bright and fast coloured value-added diversified products made from jute.

Cultural significance

National symbols

National Emblem of Bangladesh. Above the water lilly are four stars and three connected jute leaves.

National Emblem of Bangladesh. Above the water lilly are four stars and three connected jute leaves. State emblem of Pakistan, Jute depicted in the fourth quarter

State emblem of Pakistan, Jute depicted in the fourth quarter

See also

References

- ↑ Plants for a Future, retrieved 21 May 2015

- ↑ Indian Jute : Medicinal use/Herbal Use of Jute (Jute Leaves, etc.), retrieved 17 August 2015

- ↑ The New Bantam-Megiddo Hebrew & English Dictionary, Sivan and Levenston, Bantam books, NY, 1875

- ↑ Chiffolo, Anthony F; Rayner W. Hesse (30 August 2006). Cooking With the Bible: Biblical Food, Feasts, And Lore. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 237. ISBN 9780313334108. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ↑ "BBC Two - Brian Cox's Jute Journey". BBC. 2010-02-24. Retrieved 2016-09-20.

- 1 2 Jute. (IJSG). Retrieved 13 June 2007.

- ↑ "Office of the Jute Commissioner — Ministry of Textiles". www.jutecomm.gov.in. 2013-11-19. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- ↑ "Statistics — World production of Jute Fibres from 2004/2005 to 2010/2011". International Jute Study Group (IJSG). 2013-11-19. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- ↑ "Statistics — World Import of raw Jute, Kenaf and Allied Fibres". International Jute Study Group (IJSG). 2013-11-19. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- ↑ "Statistics — World Imports of Products of Jute, Kenaf and Allied Fibres". International Jute Study Group (IJSG). 2013-11-19. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- ↑ "FAOSTAT – Crops" (Query page requires interactive entry in four sections: "Countries"–Select All; "Elements"–Production Quantity; "Items"–Jute; "Years"–2014). Food And Agricultural Organization of United Nations: Economic And Social Department: The Statistical Division. 2017-02-13. Retrieved 2017-02-17.

- ↑ "The Jute Genome Project Homepage". Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ "SUGAR AND JUTE AEROPLANE PANELS".

- ↑ "WHAT IS JUTE AND JUCO?".

- ↑ The Golden Fiber Trade Centre Limited. (GFTCL) - Articles & Information on Jute, Kenaf, & Roselle Hemp.

- ↑ AVRDC. Recipes - African Sticky Soup (Ewedu). Retrieved 27 June 2013.

Further reading

- Basu, G., A. K. Sinha, and S. N. Chattopadhyay. "Properties of Jute Based Ternary Blended Bulked Yarns". Man-Made Textiles in India. Vol. 48, no. 9 (Sep. 2005): 350–353. (AN 18605324)

- Chattopadhyay, S. N., N. C. Pan, and A. Day. "A Novel Process of Dyeing of Jute Fabric Using Reactive Dye". Textile Industry of India. Vol. 42, no. 9 (Sep. 2004): 15–22. (AN 17093709)

- Doraiswamy, I., A. Basu, and K. P. Chellamani. "Development of Fine Quality Jute Fibers". Colourage. Nov. 6–8, 1998, 2p. (AN TDH0624047199903296)

- Kozlowski, R., and S. Manys. "Green Fibers". The Textile Institute. Textile Industry: Winning Strategies for the New Millennium—Papers Presented at the World Conference. Feb. 10–13, 1999: 29 (13p). (AN TDH0646343200106392)

- Madhu, T. "Bio-Composites—An Overview". Textile Magazine. Vol. 43, no. 8 (Jun. 2002): 49 (2 pp). (AN TDH0656367200206816)

- Maulik, S. R. "Chemical Modification of Jute". Asian Textile Journal. Vol. 10, no. 7 (Jul. 2001): 99 (8 pp). (AN TDH0648424200108473)

- Moses, J. Jeyakodi, and M. Ramasamy. "Quality Improvement on Jute and Jute Cotton Materials Using Enzyme Treatment and Natural Dyeing". Man-Made Textiles in India. Vol. 47, no. 7 (Jul. 2004): 252–255. (AN 14075527)

- Pan, N. C., S. N. Chattopadhyay, and A. Day. "Dyeing of Jute Fabric with Natural Dye Extracted from Marigold Flower". Asian Textile Journal. Vol. 13, no. 7 (Jul. 2004): 80–82. (AN 15081016)

- Pan, N. C., A. Day, and K. K. Mahalanabis. "Properties of Jute". Indian Textile Journal. Vol. 110, no. 5 (Feb. 2000): 16. (AN TDH0635236200004885)

- Roy, T. K. G., S. K. Chatterjee, and B. D. Gupta. "Comparative Studies on Bleaching and Dyeing of Jute after Processing with Mineral Oil in Water Emulsion vis-a-vis Self-Emulsifiable Castor Oil". Colourage. Vol. 49, no. 8 (Aug. 2002): 27 (5 pp). (AN TDH0657901200208350)

- Shenai, V. A. "Enzyme Treatment". Indian Textile Journal. Vol. 114, no. 2 (Nov. 2003): 112–113. (AN 13153355)

- Srinivasan, J., A. Venkatachalam, and P. Radhakrishnan. "Small-Scale Jute Spinning: An Analysis". Textile Magazine. Vol. 40, no. 4 (Feb. 1999): 29. (ANTDH0624005199903254)

- Tomlinson, Jim. Carlo Morelli and Valerie Wright. The Decline of Jute: Managing Industrial Decline (London: Pickering and Chatto, 2011) 219 pp. ISBN 978-1-84893-124-4. focus on Dundee, Scotland

- Vijayakumar, K. A., and P. R. Raajendraa. "A New Method to Determine the Proportion of Jute in a Jute/Cotton Blend". Asian Textile Journal, Vol. 14, no. 5 (May 2005): 70-72. (AN 18137355)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jute. |

| Look up jute in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Jute Genome Project

- Bangladesh Jute Research Institute

- International Jute Study Group (IJSG) Resources about jute, kenaf and roselle plants. jute.org

- Department of Horticulture & Landscape Architecture, Purdue University Some chemistry and medicinal information on tossa jute. purdue.edu

- National Library of Scotland: SCOTTISH SCREEN ARCHIVE (selection of archive films about the jute industry in Dundee)