Himalia (moon)

|

Himalia as seen by spacecraft Cassini | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | C. D. Perrine |

| Discovery date | December 3, 1904[1] |

| Designations | |

| Adjectives | Himalian |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| Periapsis | 9,782,900 km |

| Apoapsis | 13,082,000 km |

Mean orbit radius | 11,460,000 km[2] |

| Eccentricity | 0.16[2] |

| 250.56 d (0.704 a)[2] | |

Average orbital speed | 3.312 km/s |

| Inclination | |

| Satellite of | Jupiter |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean radius |

75±10 × 60±10 km (Cassini estimate)[3] 85 ± ?? km[4] (ground-based estimate)[3] |

| ~90,800 km2 | |

| Volume | ~2,570,000 km3 |

| Mass |

6.7×1018 kg[4] 4.19×1018 kg[5] |

Mean density |

2.6 g/cm3 (assumed)[4] 1.63 g/cm3 (assuming radius 85 km)[5][6] |

| ~0.062 m/s2 (0.006 g) | |

| ~0.100 km/s | |

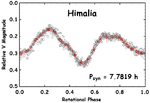

Sidereal rotation period | 7.782 h[7] |

| Albedo | 0.04[4][3] |

| Temperature | ~124 K |

| 14.6[4] | |

|

| |

Himalia (/haɪˈmeɪliə/ hy-MAY-lee-ə or /hɪˈmɑːliə/ hi-MAH-lee-ə; Greek: Ἱμαλία) is the largest irregular satellite of Jupiter. It is the sixth largest Jovian satellite overall in size, and only the four Galilean moons of Jupiter have greater mass. It was discovered by Charles Dillon Perrine at the Lick Observatory on 3 December 1904 and is named after the nymph Himalia, who bore three sons of Zeus (the Greek equivalent of Jupiter). It is one of the largest planetary moons in the Solar System not imaged in detail, and the largest not including the moons of Neptune and several trans-Neptunian objects, particularly Dysnomia, the moon of Eris.[1]

Discovery

Himalia was discovered by Charles Dillon Perrine at the Lick Observatory on 3 December 1904.[1] Himalia is Jupiter's most easily observed small satellite; though Amalthea is brighter, its proximity to the planet's brilliant disk makes it a far more difficult object to view.[8][9]

Name

Himalia is named after the nymph Himalia, who bore three sons of Zeus (the Greek equivalent of Jupiter). The moon did not receive its present name until 1975;[10] before then, it was simply known as Jupiter VI or Jupiter Satellite VI, although calls for a full name appeared shortly after its and Elara's discovery; A.C.D. Crommelin wrote in 1905:

Unfortunately the numeration of Jupiter's satellites is now in precisely the same confusion as that of Saturn's system was before the numbers were abandoned and names substituted. A similar course would seem to be advisable here; the designation V for the inner satellite [Amalthea] was tolerated for a time, as it was considered to be in a class by itself; but it has now got companions, so that this subterfuge disappears. The substitution of names for numerals is certainly more poetic.[11]

The moon was sometimes called Hestia, after the Greek goddess, from 1955 to 1975.[12]

Orbit

At a distance of about 11.5 million km from Jupiter, Himalia takes about 251 Earth days to complete one orbit.[13] It is the largest member of the group that bears its name, the moons orbiting between 11.4 and 13 million kilometers from Jupiter at an inclination of about 27.5°.[14] The orbital elements are as of January 2000.[2] They are continuously changing due to solar and planetary perturbations.

Physical characteristics

Himalia's rotational period is 7 h 46 m 55±2 s.[7] Himalia appears neutral in color (grey), like the other members of its group, with colour indices B−V=0.62, V−R=0.4, similar to a C-type asteroid.[15] Measurements by Cassini confirm a featureless spectrum, with a slight absorption at 3 µm, which could indicate the presence of water.[16]

Mass

In 2005, Emelyanov estimated Himalia to have a mass of 4.19×1018 kg (GM=0.28), based on a perturbation of Elara on July 15, 1949.[5] JPL's Solar System dynamics web site assumes that Himalia has a mass of 6.7×1018 kg (GM=0.45) with a radius of 85 km.[4]

Himalia's density will depend on whether it has an average radius of about 67 km (geometric mean from Cassini)[5] or a radius closer to 85 km.[4]

| Source | Radius km | Density g/cm³ | Mass kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emelyanov | 67 | 3.33 | 4.19×1018 |

| Emelyanov | 85 | 1.63[6] | 4.19×1018 |

| JPL SSD | 85 | 2.6 | 6.7×1018 |

Exploration

In November 2000, the Cassini spacecraft, en route to Saturn, made a number of images of Himalia, including photos from a distance of 4.4 million km. Himalia covers only a few pixels, but seems to be an elongated object with axes 150±20 and 120±20 km, close to the Earth-based estimations.[3]

In February and March 2007, the New Horizons spacecraft en route to Pluto made a series of images of Himalia, culminating in photos from a distance of 8 million km. Again, Himalia appears only a few pixels across.

Possible relationship with Jupiter's rings

The small moon Dia, 4 kilometres in diameter, had gone missing since its discovery in 2000.[17] One theory was that it had crashed into the much larger moon Himalia, 170 kilometres in diameter, creating a faint ring. This possible ring appears as a faint streak near Himalia in images from NASA's New Horizons mission to Pluto. This suggests that Jupiter sometimes gains and loses small moons through collisions.[18] However, the recovery of Dia in 2010 and 2011[19] disproves the link between Dia and the Himalia ring, although it is still possible that a different moon may have been involved.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Porter, J. G. (1905). "Discovery of a Sixth Satellite of Jupiter". Astronomical Journal. 24 (18): 154B. Bibcode:1905AJ.....24..154P. doi:10.1086/103612.;

Perrine, C. D. (1905-01-25). "Sixth Satellite of Jupiter Confirmed". Harvard College Observatory Bulletin. 175: 1. Bibcode:1905BHarO.175....1P.;

Perrine, C.D. (1905). "Discovery of a Sixth Satellite to Jupiter". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 17: 22–23. Bibcode:1905PASP...17...22.. doi:10.1086/121619.;

Perrine, C.D. (1905). "Orbits of the sixth and seventh satellites of Jupiter". Astronomische Nachrichten. 169 (3): 43–44. Bibcode:1905AN....169...43P. doi:10.1002/asna.19051690304. - 1 2 3 4 5 Jacobson, R. A. (2000). "The orbits of outer Jovian satellites". Astronomical Journal. 120 (5): 2679–2686. Bibcode:2000AJ....120.2679J. doi:10.1086/316817.

- 1 2 3 4 Porco, Carolyn C.; et al. (March 2003). "Cassini Imaging of Jupiter's Atmosphere, Satellites, and Rings" (PDF). Science. 299 (5612): 1541–1547. Bibcode:2003Sci...299.1541P. PMID 12624258. doi:10.1126/science.1079462.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters". JPL (Solar System Dynamics). 2008-10-24. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- 1 2 3 4 Emelyanov, N.V.; Archinal, B. A.; a'Hearn, M. F.; et al. (2005). "The mass of Himalia from the perturbations on other satellites". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 438 (3): L33–L36. Bibcode:2005A&A...438L..33E. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200500143.

- 1 2 Density = GM / G / (Volume of a sphere of 85km) = 1.63 g/cm3

- 1 2 3 Pilcher, Frederick; Mottola, Stefano; Denk, Tilmann (2012). "Photometric lightcurve and rotation period of Himalia (Jupiter VI)". Icarus. 219 (2): 741–742. Bibcode:2012Icar..219..741P. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2012.03.021.

- ↑ "Himalia, Jupiter's "fifth" moon". Archived from the original on July 19, 2011.

- ↑ "Finding Himalia, The Fifth Brightest Moon Of Jupiter - an Astronomy Net Article". Astronomy.net. 2003-10-20. Retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ↑ Marsden, B. G. (7 October 1974). "Satellites of Jupiter". IAUC Circular. 2846.

- ↑ Crommelin, A. C. D. (March 10, 1905). "Provisional Elements of Jupiter's Satellite VI". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 65 (5): 524–527. Bibcode:1905MNRAS..65..524C. doi:10.1093/mnras/65.5.524.

- ↑ Payne-Gaposchkin, Cecilia; Katherine Haramundanis (1970). Introduction to Astronomy. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-478107-4.

- ↑ "Himalia: Overview". NASA. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ↑ Jewitt, David C.; Sheppard, Scott & Porco, Carolyn (2004). "Jupiter's Outer Satellites and Trojans". In Bagenal, F.; Dowling, T. E. & McKinnon, W. B. Jupiter: The planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere (PDF). Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Rettig, T. W.; Walsh, K.; Consolmagno, G. (December 2001). "Implied Evolutionary Differences of the Jovian Irregular Satellites from a BVR Color Survey". Icarus. 154 (2): 313–320. Bibcode:2001Icar..154..313R. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6715.

- ↑ Chamberlain, Matthew A.; Brown, Robert H. (2004). "Near-infrared spectroscopy of Himalia". Icarus. 172 (1): 163–169. Bibcode:2004Icar..172..163C. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2003.12.016.

- ↑ IAUC 7555 (January 2001). "FAQ: Why don't you have Jovian satellite S/2000 J11 in your system?". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- ↑ "Lunar marriage may have given Jupiter a ring", New Scientist, March 20, 2010, p. 16.

- ↑ Gareth V. Williams (2012-09-11). "MPEC 2012-R22 : S/2000 J 11". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 2012-09-11.

External links

- "Himalia: Overview" by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- David Jewitt pages

- Jupiter's Known Satellites (by Scott S. Sheppard)

- Two Irregular Satellites of Jupiter (Himalia & Elara: Remanzacco Observatory: November 23, 2012)