The Jungle Book (1967 film)

| The Jungle Book | |

|---|---|

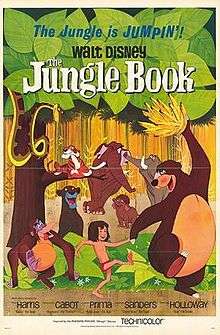

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Wolfgang Reitherman |

| Produced by | Walt Disney |

| Story by |

Larry Clemmons Ralph Wright Ken Anderson Vance Gerry Floyd Norman (uncredited)[1] Bill Peet (uncredited)[2] |

| Based on |

The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling |

| Starring |

Phil Harris Sebastian Cabot Louis Prima George Sanders Sterling Holloway J. Pat O'Malley Bruce Reitherman |

| Narrated by | Sebastian Cabot |

| Music by |

George Bruns (Score) Terry Gilkyson Richard M. Sherman Robert B. Sherman (Songs) |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 78 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4 million |

| Box office | $205.8 million[3] |

The Jungle Book is a 1967 American animated musical adventure film produced by Walt Disney Productions. Inspired by Rudyard Kipling's book of the same name, it is the 19th Disney animated feature film. Directed by Wolfgang Reitherman, it was the last film to be produced by Walt Disney, who died during its production. The plot follows Mowgli, a feral child raised in the Indian jungle by wolves, as his friends Bagheera the panther and Baloo the bear try to convince him to leave the jungle before the evil tiger Shere Khan arrives.

The early versions of both the screenplay and the soundtrack followed Kipling's work more closely, with a dramatic, dark, and sinister tone which Disney did not want in his family film, leading to writer Bill Peet and composer Terry Gilkyson being replaced. The casting employed famous actors and musicians Phil Harris, Sebastian Cabot, George Sanders and Louis Prima, as well as Disney regulars such as Sterling Holloway, J. Pat O'Malley and Verna Felton, and the director's son, Bruce Reitherman, as Mowgli.

The Jungle Book was released on October 18, 1967, to positive reception, with acclaim for its soundtrack, featuring five songs by the Sherman Brothers and one by Gilkyson, "The Bare Necessities". The film grossed over $23.8 million worldwide in its first release,[4] and as much again from two re-releases. Disney released a live-action remake in 1994 and an animated sequel, The Jungle Book 2, in 2003; another live-action adaptation directed by Jon Favreau was released in 2016.

Plot

Mowgli, a young orphan boy, is found in a basket in the deep jungles of India by Bagheera, a black panther who promptly takes him to a mother wolf who has just had cubs. She raises him along with her own cubs and Mowgli soon becomes well acquainted with jungle life. Mowgli is shown ten years later, playing with his wolf siblings.

One night, when the wolf tribe learns that Shere Khan, a man-eating Bengal tiger, has returned to the jungle, they realize that Mowgli must be taken to the "Man-Village" for his (and their) own safety. Bagheera volunteers to escort him back. They leave that very night, but Mowgli is determined to stay in the jungle. He and Bagheera rest in a tree for the night, where Kaa, a hungry python, tries to devour Mowgli, but Bagheera intervenes. The next morning, Mowgli tries to join the elephant patrol led by Colonel Hathi and his wife Winifred. Bagheera finds Mowgli, but after a fight decides to leave Mowgli on his own. Mowgli soon meets up with the laid-back, fun-loving bear Baloo, who promises to raise Mowgli himself and never take him back to the Man-Village.

Shortly afterwards, a group of monkeys kidnap Mowgli and take him to their leader, King Louie the orangutan. King Louie offers to help Mowgli stay in the jungle if he will tell Louie how to make fire like other humans. However, since he was not raised by humans, Mowgli does not know how to make fire. Bagheera and Baloo arrive to rescue Mowgli and in the ensuing chaos, King Louie's palace is demolished to rubble. Bagheera speaks to Baloo that night and convinces him that the jungle will never be safe for Mowgli so long as Shere Khan is there. In the morning, Baloo reluctantly explains to Mowgli that the Man-Village is best for the boy, but Mowgli accuses him of breaking his promise and runs away. As Baloo sets off in search of Mowgli, Bagheera rallies the help of Hathi and his patrol. However, Shere Khan himself, who was eavesdropping on Bagheera and Hathi's conversation, is now determined to hunt and kill Mowgli himself.

Meanwhile, Mowgli has encountered Kaa once again, but thanks to the unwitting intervention of the suspicious Shere Khan, Mowgli escapes. As a storm gathers, a depressed Mowgli encounters a group of friendly vultures who accept Mowgli as a fellow outcast. Shere Khan appears shortly after, scaring off the vultures and confronting Mowgli. Baloo rushes to the rescue and tries to keep Shere Khan away from Mowgli, but is injured. When lightning strikes a nearby tree and sets it ablaze, the vultures swoop in to distract Shere Khan while Mowgli gathers flaming branches and ties them to Shere Khan's tail. Terrified of fire, the tiger panics and runs off.

Bagheera and Baloo take Mowgli to the edge of the Man-Village, but Mowgli is still hesitant to go there. His mind soon changes when he is smitten by a beautiful young girl from the village who is coming down by the riverside to fetch water. After noticing Mowgli, she "accidentally" drops her water pot. Mowgli retrieves it for her and follows her into the Man-Village. After Mowgli chooses to stay in the Man-Village, Baloo and Bagheera decide to head home, content that Mowgli is safe and happy with his own kind.

Cast

- Bruce Reitherman as Mowgli, an orphaned boy, commonly referred to as "man-cub" by the other characters.

- Phil Harris as Baloo, a sloth bear who leads a carefree life and believes in letting the good things in life come by themselves.

- Sebastian Cabot as Bagheera, a serious black panther who is determined to take Mowgli back to the village and disapproves of Baloo's carefree approach to life.

- Louis Prima as King Louie, an orangutan who wants to be a human, and wants Mowgli to teach him how to make fire.

- George Sanders as Shere Khan, an intelligent and sophisticated yet merciless Bengal tiger who hates all humans for fear of their guns and fire and wants to kill Mowgli.

- Sterling Holloway as Kaa, an Indian python who also seeks Mowgli as prey, but comically fails each time he attempts to eat him.

- J. Pat O'Malley as Colonel Hathi the Indian elephant/Buzzie the Vulture

- Verna Felton as Winifred, Colonel Hathi's wife.

- Clint Howard as Junior, Colonel Hathi's son.

- Chad Stuart as Flaps the Vulture

- Lord Tim Hudson as Dizzie the Vulture

- John Abbott as Akela the Indian wolf

- Ben Wright as Rama the Father Wolf

- Darleen Carr as The Human Girl

- Leo De Lyon as Flunkey the Langur*

- Hal Smith as The Slob Elephant*

- Ralph Wright as The Gloomy Elephant*

- Digby Wolfe as Ziggy the Vulture*

- Bill Skiles and Pete Henderson as Monkeys*

Asterisks mark actors listed in the opening credits as "Additional Voices".[5][6][7]

Production

Development and writing

After The Sword in the Stone was released, storyman Bill Peet claimed to Walt Disney that "we [the animation department] can do more interesting animal characters" and suggested that Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book could be used for the studio's next film.[8] Disney agreed and Peet created an original treatment, with little supervision, as he had done with One Hundred and One Dalmatians and The Sword in the Stone. However, after the disappointing reaction to The Sword in the Stone, Walt Disney decided to become more involved in the story than he had been with the past two films,[9] with his nephew Roy E. Disney saying that "[he] certainly influenced everything about it. (...) With Jungle Book, he obviously got hooked on the jungle and the characters that lived there."[10]

Peet decided to follow closely the dramatic, dark, and sinister tone of Kipling's book, which is about the struggles between animals and man. However, the film's writers decided to make the story more straightforward, as the novel is very episodic, with Mowgli going back and forth from the jungle to the Man-Village, and Peet felt that Mowgli returning to the Man-Village should be the ending for the film. Following suggestions, Peet also created two original characters: The human girl for which Mowgli falls in love, as the animators considered that falling in love would be the best excuse for Mowgli to leave the jungle; and Louie, king of the monkeys. Louie was a less comical character, enslaving Mowgli trying to get the boy to teach him to make fire. The orangutan would also show a plot point borrowed from The Second Jungle Book, gold and jewels under his ruins — after Mowgli got to the man village, a poacher would drag the boy back to the ruins in search for the treasure.[2][9] Disney was not pleased with how the story was turning out, as he felt it was too dark for family viewing and insisted on script changes. Peet refused, and after a long argument, Peet left the Disney studio in January 1964.[8]

Disney then assigned Larry Clemmons as his new writer and one of the four story men for the film, giving Clemmons a copy of Kipling's book, and telling him: "The first thing I want you to do is not to read it."[9] Clemmons still looked at the novel, and thought it was too disjointed and without continuity, needing adaptations to fit a film script. Clemmons wanted to start in medias res, with some flashbacks afterwards, but then Disney said to focus on doing the storyline more straight - "Let's do the meat of the picture. Let's establish the characters. Let's have fun with it.".[11] Although much of Bill Peet's work was discarded, the personalities of the characters remained in the final film. This was because Disney felt that the story should be kept simple, and the characters should drive the story. Disney took an active role in the story meetings, acting out each role and helping to explore the emotions of the characters, help create gags and develop emotional sequences.[9] Clemmons would write a rough script with an outline for most sequences. The story artists then discussed how to fill the scenes, including the comedic gags to employ.[1][12] The script also tried to incorporate how the voice actors molded their characters and interacted with each other.[13] The Jungle Book also marks the last animated film from the company to have Disney's personal touches, before his death on December 15, 1966.[14]

Casting

—Wolfgang Reitherman[13]

Many familiar voices inspired the animators in their creation of the characters[9] and helped them shape their personalities.[14] This use of familiar voices for key characters was a rarity in Disney's past films.[9] The staff was shocked to hear that a wise cracking comedian, Phil Harris was going to be in a Kipling film. Disney suggested Harris after meeting him at a party.[15] Harris improvised most of his lines, as he considered the scripted lines "didn't feel natural".[8] After Harris was cast, Disneyland Records president Jimmy Johnson suggested Disney to get Louis Prima as King Louie, as he "felt that Louis would be great as foil".[16] Walt also cast other prominent actors such as George Sanders as Shere Khan and Sebastian Cabot as Bagheera. Additionally, he cast regular Disney voices such as Sterling Holloway as Kaa, J. Pat O'Malley as Colonel Hathi and Buzzie the Vulture and Verna Felton as Hathi's wife. This was her last film before she died.[14] David Bailey was originally cast as Mowgli, but his voice changed during production, leading Bailey to not fit the "young innocence of Mowgli's character" at which the producers were aiming. Thus director Wolfgang Reitherman cast his son Bruce, who had just voiced Christopher Robin in Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree. The animators shot footage of Bruce as a guide for the character's performance.[8][17] Child actress Darlene Carr was going around singing in the studio when composers Sherman Brothers asked her to record a demo of "My Own Home". Carr's performance impressed Disney enough for him to cast her as the role of the human girl.[18]

In the original book, the vultures are grim and evil characters who feast on the dead. Disney lightened it up by having the vultures bearing a physical and vocal resemblance to The Beatles, including the signature mop-top haircut. It was also planned to have the members of the band to both voice the characters and sing their song, "That's What Friends Are For". However, the Beatles member John Lennon's refusal to work on animated films in that period led to the idea being discarded.[19] The casting of the vultures still brought a British Invasion musician, Chad Stuart of the duo Chad & Jeremy.[8] In earlier drafts of the scene the vultures had a near-sighted rhinoceros friend named Rocky, who was to be voiced by Frank Fontaine. However, Walt decided to cut the character for feeling that the film had already much action with the monkeys and vultures.[20]

Animation

While many of the later Disney feature films had animators being responsible for single characters, in The Jungle Book the animators were in charge of whole sequences, since many have characters interacting with one another. The animation was done by xerography, with character design, led by Ken Anderson, employing rough, artistic edges in contrast to the round animals seen in productions such as Dumbo.[21]

Anderson also decided to make Shere Khan resemble his voice actor, George Sanders.[8] Backgrounds were hand-painted — with exception of the waterfall, mostly consisting of footage of the Angel Falls - and sometimes scenery was used in both foreground and bottom to create a notion of depth. Following one of Reitherman's trademarks of reusing animation of his previous films, the wolf cubs are based on dogs from 101 Dalmatians. Animator Milt Kahl based Bagheera and Shere Khan's movements on live-action felines, which he saw in two Disney productions, A Tiger Walks and the "Jungle Cat" episode of True-Life Adventures.[21]

Baloo was also based on footage of bears, even incorporating the animal's penchant for scratching. Since Kaa has no limbs, its design received big expressive eyes, and parts of Kaa's body did the action that normally would be done with hands.[22] The monkeys' dance during "I Wan'na Be Like You" was partially inspired by a performance Louis Prima did with his band at Disney's soundstage to convince Walt Disney to cast him.[8]

Music

The instrumental music was written by George Bruns and orchestrated by Walter Sheets. Two of the cues were reused from previous Disney films. The scene where Mowgli wakes up after escaping King Louie used one of Bruns' themes for Sleeping Beauty; and the scene where Bagheera gives a eulogy to Baloo when he mistakenly thinks the bear was killed by Shere Khan used Paul J. Smith's organ score from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.[23]

The score features eight original songs: seven by the Sherman Brothers and one by Terry Gilkyson. Longtime Disney collaborator Gilkyson was the first songwriter to bring several complete songs which followed the book closely but Walt Disney felt that his efforts were too dark. The only piece of Gilkyson's work which survived to the final film was his upbeat tune "The Bare Necessities", which was liked by the rest of the film crew. The Sherman Brothers were then brought in to do a complete rewrite.[8] Disney asked the siblings if they had read Kipling's book and they replied that they had done so "a long, long time ago" and that they had also seen the 1942 version by Alexander Korda. Disney said the "nice, mysterious, heavy stuff" from both works was not what he aimed for, instead going for a "lightness, a Disney touch".[24] Disney frequently brought the composers to the storyline sessions.[8] He asked them to "find scary places and write fun songs" for their compositions[23] that fit in with the story and advanced the plot instead of being interruptive.[8]

Release and reception

Theatrical run

The Jungle Book was released in October 1967,[9] just 10 months after Walt's death.[14] Some copies were in a double feature with Charlie, the Lonesome Cougar.[25] Produced on a budget of $4 million,[26][27] the film was a massive success, finishing 1967 as the fourth highest-grossing movie of the year.[28] The Jungle Book was re-released theatrically in North America three times, 1978, 1984, and 1990, and also in Europe throughout the 1980s.[29] The total gross is $141 million in the United States and $205 million worldwide.[3] The North American total, after adjustments for inflation, is estimated to be the 29th highest-grossing film of all time in the United States.[30] An estimated $108 million alone came from Germany making it the third highest-grossing film of all time there only behind Avatar ($137 million) and Titanic ($125 million).[31] However, it is Germany's highest-grossing film of all time in terms of admissions with 27.3 million tickets sold, nearly 10 million more than Titanic's 18.8 million tickets sold.[32]

Home media

The Jungle Book was released in the United States on VHS in 1991 as part of the Walt Disney Classics product line. Home video sales outside North America totaled 14.8 million units by January 1994.[33] It was reissued on video in 1997 as part of the Walt Disney Masterpiece Collection for the film's 30th anniversary.[29] A Limited Issue DVD was released by Buena Vista Home Entertainment in 1999.[34] The film was released once again as a 2-disc Platinum Edition DVD on October 2, 2007 to commemorate its 40th anniversary.[35] Its release was accompanied by a limited 18-day run at Disney's own El Capitan Theatre in Los Angeles, with the opening night featuring a panel with composer Richard Sherman and voice actors Bruce Reitherman, Darlene Carr and Chad Stuart.[36] The Platinum DVD was put on moratorium in 2010.[37] The film was released in a Blu-Ray/DVD/Digital Copy Combo pack on February 11, 2014 as part of Disney's Diamond Edition line.[38] The Diamond Edition release went back into the Disney Vault on January 31, 2017.

Critical reception

The Jungle Book received positive reviews upon release, undoubtedly influenced by a nostalgic reaction to the death of Disney.[14] Time noted that the film strayed far from the Kipling stories, but "the result is thoroughly delightful...it is the happiest possible way to remember Walt Disney."[14] The New York Times called it "a perfectly dandy cartoon feature,"[25] and Life magazine referred to it as "the best thing of its kind since Dumbo, another short, bright, unscary and blessedly uncultivated cartoon."[39] Variety's review was generally positive, but they stated that "the story development is restrained" and that younger audiences "may squirm at times."[14] The song "The Bare Necessities" was nominated for Best Song at the 40th Academy Awards, losing to "Talk to the Animals" from Doctor Dolittle.[40] Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences president Gregory Peck lobbied extensively for this film to be nominated for Best Picture, but was unsuccessful.[41]

Retrospective reviews were also positive, with the film's animation, characters and music receiving much praise throughout the years. On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 86%.[42] In 1990, when the film had its last theatrical re-release, Entertainment Weekly considered that The Jungle Book "isn't a classic Walt Disney film on the order of, say, Cinderella or Pinocchio, but it's one of Disney's liveliest and funniest",[43] while the Los Angeles Times thought the film's crew was "near the height of their talents" and the resulting film "remains a high-spirited romp that will delight children--and parents weary of action films with body counts that exceed their box-office grosses."[44] In 2010, Empire' ' described the film as one that "gets pretty much everything right", regarding that the vibrant animation and catchy songs overcame the plot deficiencies.[41]

American Film Institute lists:

[AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs|AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

The Bare Necessities - Nominated

I wanna be like you - Nominated

Legacy

In 1968, Disneyland Records released the album More Jungle Book, an unofficial sequel also written by screenwriter Larry Simmons, which continued the story of the film, and included Phil Harris and Louis Prima voicing their film roles. In the record, Baloo (Harris) is missing Mowgli (Ginny Tyler), so he teams up with King Louie (Prima) and Bagheera (Dal McKennon) to take him from the man village.[45] On February 14, 2003, DisneyToon Studios in Australia released a film sequel, The Jungle Book 2, in which Mowgli runs away from the man village to see his animal friends, unaware that Shere Khan is more determined to kill him than ever.[46] In 2005, screenwriter Robert Reece pitched Jungle Book 3 to Disney execs. However, the project never materialized.[47]

Elements of The Jungle Book were recycled in the later Disney feature film Robin Hood due to that film's limited budget, such as Baloo being inspiration for Little John (who not only was a bear, but also voiced by Phil Harris). In particular, the dance sequence between Baloo and King Louie was simply rotoscoped for Little John and Lady Cluck's dance.[48] It has been widely acclaimed by animators, with Eric Goldberg declaring The Jungle Book "boasts possibly the best character animation a studio has ever done". The animators of Aladdin, The Lion King and Lilo & Stitch took inspiration from the design and animation of the film, and four people involved with Disney's animations, director Brad Bird and animators Andreas Deja, Glen Keane and Sergio Pablos, have declared the film to be their inspiration for entering the business.[49]

Many characters appear in the 1990–91 animated series TaleSpin.[50] Between 1996 and 1998, the TV series Jungle Cubs told the stories of Baloo, Hahti, Bagheera, Louie, Kaa, and Shere Khan when they were children.[51] Disney later made a live-action remake of the film, which was more of a realistic action-adventure film with somewhat-more adult themes. The film, released in 1994, differs even more from the book than its animated counterpart, but was still a box-office success. In 1998, Disney released a direct to video film entitled The Jungle Book: Mowgli's Story.[52] A new live-action version of The Jungle Book was released by Disney in 2016, which even reused most of the songs of the animated movie, with some lyrical reworking by original composer Richard M. Sherman.[53]

There are two video games based on the film: The Jungle Book was a platformer released in 1993 for Master System, Mega Drive, Game Gear, Super NES, Game Boy and PC. A version for the Game Boy Advance was later released in 2003.[54] The Jungle Book Groove Party was a dance mat game released in 2000 for PlayStation and PlayStation 2.[55][56] Kaa and Shere Khan have also made cameo appearances in another Disney video game, Quackshot.[57] A world based on the film was intended to appear more than once in the Square Enix-Disney Kingdom Hearts video game series, but was omitted both times, first in the first game because it featured a similar world based on Tarzan,[58] and second in Kingdom Hearts: Birth by Sleep, although areas of the world are accessible via hacking codes.[59]

Since the film's release, many of the film's characters appeared in House of Mouse, The Lion King 1½, Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and Aladdin and the King of Thieves.[60] In December 2010, a piece of artwork by British artist Banksy featuring The Jungle Book characters which had been commissioned by Greenpeace to help raise awareness of deforestation went on sale for the sum of £80,000.[61]

See also

References

- 1 2 Beiman, Nancy (2007). Prepare to board!: creating story and characters for animated features and shorts. Focal Press. ISBN 978-0-240-80820-8.

- 1 2 Disney's Kipling: Walt's Magic Touch on a Literary Classic. The Jungle Book, Platinum Edition, Disc 2. 2007.

- 1 2 "The Jungle Book". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ↑ "Animals Portray Parts in Disney's "Robin Hood"". Toledo Blade. October 18, 1970. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ↑ Beck, Jerry (2005). The animated movie guide. Chicago Review Press. p. 133. ISBN 1-55652-591-5.

- ↑ Hischak, Thomas S. (2011). Disney Voice Actors: A Biographical Dictionary. McFarland. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-7864-6271-1.

- ↑ Webb, Graham S. (2000). The animated film encyclopedia: a complete guide to American shorts, features and sequences 1900-1979. McFarland. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-7864-0728-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Barrier, Michael (2008). The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. University of California Press. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-520-25619-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Thomas, Bob: "Chapter 7: The Post-War Films," section: "Walt Disney's Last Films", pages 106-107. Disney's Art of Animation: From Mickey Mouse to Hercules, 1997

- ↑ The Legacy of the Jungle Book. The Jungle Book 2 DVD: Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2003.

- ↑ Larry Clemmons. The Jungle Book audio commentary. The Jungle Book — Platinum Edition

- ↑ Norman, Floyd (2010). Ghez, Didier, ed. Walt's People -, Volume 9. Xlibris Corporation. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-4500-8746-9.

- 1 2 Crown (1980). Walt Disney's The jungle book. Harmony Books. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-517-54328-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Maltin, Leonard: "Chapter 2," section: "The Jungle Book", pages 253-256. The Disney Films, 2000

- ↑ Wolfgang Reitherman. The Jungle Book audio commentary. The Jungle Book — Platinum Edition

- ↑ Hollis, Tim; Ehrbar, Greg (2006). Mouse tracks: the story of Walt Disney Records. Univ. Press of Mississippi. pp. 89, 90. ISBN 978-1-57806-849-4.

- ↑ Bruce Reitherman (2007). The Jungle Book audio commentary. The Jungle Book, Platinum Edition, Disc 1.

- ↑ Sherman, Robert B., Walt's Time: from before to beyond, Camphor Tree Publishers, Santa Clarita, California, 1998, p 84.

- ↑ McLean, Craig (July 30, 2013). "The Jungle Book: the making of Disney's most troubled film". The Telegraph. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Lost Character: Rocky the Rhino", The Jungle Book Platinum Edition Disc 1

- 1 2 Andreas Deja (2007). The Jungle Book audio commentary. The Jungle Book, Platinum Edition, Disc 1.

- ↑ Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston Discuss Character Animation. The Jungle Book, Platinum Edition, Disc 2. 2007.

- 1 2 Richard Sherman (2007). The Jungle Book audio commentary. The Jungle Book, Platinum Edition, Disc 1.

- ↑ Sherman, Robert B.; Sherman, Richard M. (1990). Interview with the Sherman Brothers (audio track). The Jungle Book soundtrack, 30th Anniversary Edition (1997): Walt Disney Records.

- 1 2 Thompson, Howard (December 23, 1967). "Disney 'Jungle Book' Arrives Just in Time". The New York Times. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ↑ DiPrisco, Mike (September 2, 2012). "Ranking Disney: #12 – The Jungle Book (1967)". B+ Movie Blog. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ↑ "The.Jungle.Book.(1967).SE.DVD9.PAL-DVD-ED2K [EN/ES/PT/HB]". sharethefiles.com. March 19, 2008. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ↑ Krämer, Peter (2005). The new Hollywood: from Bonnie and Clyde to Star Wars. Wallflower Press. pp. 56. ISBN 978-1-904764-58-8.

- 1 2 Jones, Steve; Jensen, Joli (2005). Afterlife as afterimage: understanding posthumous fame. Peter Lang. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-8204-6365-0.

- ↑ "All Time Box Office Adjusted for Ticket Price Inflation". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ↑ Scott Roxborough (January 11, 2016). "German Box Office: 'Star Wars' Becomes Fourth Highest-Grossing Film of All Time". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ↑ Scott Roxborough (April 22, 2016). "Why Disney's Original 'Jungle Book' Is Germany's Biggest Film of All Time". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Billboard" (PDF). Billboard. January 22, 1994. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ↑ "The Jungle Book DVD Review". Ultimate Disney. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ↑ White, Cindy (October 4, 2007). "Disney Cracks Open The Jungle Book Again". IGN. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ↑ Holleran, Scott (September 14, 2007). "'Jungle Book' Opens in Hollywood". Archived from the original on March 29, 2010. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ↑ McCutcheon, David (January 13, 2010). "Disney Vault Shuts". IGN. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ↑ Brigante, Ricky (February 11, 2014). "Review: "The Jungle Book" Blu-ray brings home much more than bare necessities with funny, heartfelt features". InsideTheMagic. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ↑ Schickel, Richard (January 5, 1968). "Walt's Good — and Bad — Goodbye". Life. 64 (1): 11. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ↑ "1968 Oscars Nominees". Oscars.org. January 29, 2010. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- 1 2 "Your Guide To Disney's 50 Animated Features". Empire. January 29, 2010. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ↑ The Jungle Book at Rotten Tomatoes

- ↑ "Movie Review: The Jungle Book". Entertainment Weekly. August 3, 1990.

- ↑ Solomon, Charles (July 13, 1990). "MOVIE REVIEW : Kipling Reconditioned in Walt Disney's 'The Jungle Book'". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Hollis, Tim; Ehrbar, Greg (2006). Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records. University Press of Mississippi. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-61703-433-6.

- ↑ "The Jungle Book 2". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ↑ Armstrong, Josh (April 22, 2013). "From Snow Queen to Pinocchio II: Robert Reece's animated adventures in screenwriting". Animated Views. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ↑ Spanton, T. (April 21, 2009). "Toon of a kind". The Sun. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ↑ The Lure of The Jungle Book. The Jungle Book, Platinum Edition, Disc 2. 2007.

- ↑ "TaleSpin". Entertainment Weekly. September 7, 1990. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ↑ King, Susan (September 1, 1996). "Reading, Writing and Reinventing Heroes". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ↑ Nibley, Alexander (May 26, 1997). "Are Films Using Names in Vain?". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ↑ Keegan, Rebecca (January 8, 2016). "Jon Favreau brings 21st century technology to Rudyard Kipling's 1894 'The Jungle Book'". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Jungle Book — Sega Genesis: Video Games". Amazon.com. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ↑ Strohm, Axel (May 17, 2006). "Jungle Book Rhythm N'Groove Hands-On". GameSpot. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ↑ Varanini, Giancarlo (February 7, 2003). "Ubi Soft to release two Jungle Book games". GameSpot. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ↑ "QuackShot Retro Review". IGN. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ↑ Groenendijk, Ferry (August 11, 2006). "Kingdom Hearts II Tetsuya Nomura interview". Video Game Blogger. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ↑ McGeorge, Christopher (September 26, 2013). "Kingdom Hearts III: 7 Awesome Disney Worlds It Must Include". What Culture. Archived from the original on June 12, 2014. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ↑ Lyttelton, Oliver (March 14, 2013). "5 Things You Might Not Know About ‘Who Framed Roger Rabbit’". IndieWire. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ↑ Marc Rath, Marc (December 17, 2010). "Controversial Jungle Book artwork by Banksy bound for auction". Evening Post. Bristol Evening Post. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Jungle Book (1967 film). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Jungle Book (1967 film) |

- Official website

- The Jungle Book at The Big Cartoon DataBase

- The Jungle Book on IMDb

- The Jungle Book at the TCM Movie Database

- The Jungle Book at Rotten Tomatoes