Julius Nyerere

| Mwalimu Julius Nyerere | |

|---|---|

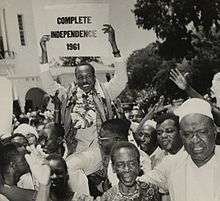

Nyerere, late 1950s. | |

| 1st President of Tanzania | |

|

In office 29 October 1964 – 5 November 1985 | |

| Vice President |

Abeid Karume Aboud Jumbe Ali Hassan Mwinyi |

| Prime Minister |

Rashidi Kawawa Edward Sokoine Cleopa Msuya Edward Sokoine Salim Ahmed Salim |

| Preceded by |

Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Tanganyika Abeid Karume as President of The People's Republic of Zanzibar and Pemba |

| Succeeded by | Ali Hassan Mwinyi |

| President of the United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar | |

|

In office 26 April 1964 – 29 October 1964 | |

| Vice-Presidents |

Abeid Karume (First) Rashidi Kawawa (Second) |

| President of Tanganyika | |

|

In office 9 December 1962 – 26 April 1964 | |

| Prime Minister | Rashidi Kawawa |

| Prime Minister of Tanganyika | |

|

In office 1 May 1961 – 22 January 1962 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Preceded by | Himself (as Chief Minister) |

| Succeeded by | Rashidi Kawawa |

| Chief Minister of Tanganyika | |

|

In office 2 September 1960 – 1 May 1961 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governor | Sir Richard Turnbull |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as Prime Minister) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Kambarage Nyerere 13 April 1922 Butiama, Tanganyika |

| Died |

14 October 1999 (aged 77) London, United Kingdom |

| Resting place | Butiama, Tanzania |

| Nationality | Tanzanian |

| Political party |

CCM (1977–1999) TANU (1954–1977) |

| Spouse(s) | Maria (m. 1953–99)[1] |

| Children |

8

|

| Alma mater |

Makerere University (DipEd) University of Edinburgh (MA) |

| Profession | Teacher |

| Awards |

Lenin Peace Prize Gandhi Peace Prize Joliot-Curie Medal |

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (Swahili pronunciation: [ˈdʒuːliəs kɑmˈbɑɾɑgə njɛˈɾɛɾɛ]; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian anti-colonial activist, politician, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika as its Prime Minister from 1961 to 1963 and then as its President from 1963 to 1964, after which he led its successor state, Tanzania, as its President from 1964 until 1985. He was a founding member of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) party and later a member of the Chama Cha Mapinduzi party. Ideologically an African nationalist and African socialist, he promoted a political philosophy known as Ujamaa.

Born in Butiama, then in the British colony of Tanganyika, Nyerere was the son of a Zanaki chief. After completing his schooling in Tanganyika, he studied at Makerere College in Uganda and then Edinburgh University in Britain. Nyerere was known by the Swahili honorific Mwalimu or 'teacher', his profession prior to politics.[2] He was also referred to as Baba wa Taifa (Father of the Nation).[3] In 1954, he helped form the Tanganyika African National Union, which was instrumental in obtaining independence for Tanganyika.

In 1967, influenced by the ideas of African socialism, Nyerere issued the Arusha Declaration, which outlined his vision of ujamaa (variously translated as "familyhood" or "socialism"; not to be confused with the Swahili word Umoja which means "unity"). Ujamaa was a concept that came to dominate Nyerere's policies. However, his policies led to economic decline, systematic corruption, and unavailability of goods. In the early 1970s, Nyerere ordered his security forces to forcibly transfer much of the population to collective farms and, because of opposition from villagers, often burned villages down. This campaign pushed the nation to the brink of starvation and made it dependent on foreign food aid. In 1985, after more than two decades in power, he relinquished power to his hand-picked successor, Ali Hassan Mwinyi. Nyerere left Tanzania as one of the poorest and most foreign aid-dependent countries in the world,[4] although much progress in services such as health and education had nevertheless been achieved.[5] He remained the chairman of the Chama Cha Mapinduzi for another five years until 1990. He died of leukemia in London in 1999.

Nyerere is still a controversial figure in Tanzania. A cult of personality revolves around him and the country's Roman Catholic community have attempted to beatify him.

Early life

Childhood: 1922–

Julius Kambarage Nyerere was born on 13 April 1922[6] in the town of Butiama in Tanganyika's Mara Region.[7][6] He was one of 26 children of Nyerere Burito, the chief of the Zanaki people.[8][9] Burito had been born in 1860 and given the name "Nyerere" ("caterpillar" in Zanaki) after a plague of worm caterpillars infested the local area at the time of his birth.[10] Burito had been appointed chief in 1915, installed in that position by the German imperial administrators of what was then German East Africa;[10] his position was also endorsed by the incoming British imperial administration.[11] Burito had 22 wives, of whom Julius' mother, Mugaya Nyang'ombe, was the fifth.[12] She had been born in 1892 and had married the chief in 1907, when she was fifteen.[13]

These wives lived in various huts around Burito's cattle corral, in the centre of which was his roundhouse.[14] The Zanaki were one of the smallest of the 120 tribes in the British colony and were then sub-divided among eight chiefdoms; they would only be united under the kingship of Chief Wanzagi Nyerere, Burito's half-brother, in the 1960s.[15] Nyerere's clan were the Abhakibhweege.[8] Nyerere was raised into the polytheistic belief system of the Zanaki,[16] and until the age of twelve, he was a cattle herder.[15]

The British colonial administration encouraged the education of chiefs' sons, believing that this would help to perpetuate the chieftain system and prevent the development of a separate educated indigenous elite who might challenge colonial governance.[17] At the age of twelve, Nyerere was sent to the Musoma Native Authority School in Butiama, about 26 miles from his home.[15] It was around this age that he began to take an interest in Roman Catholicism, although was initially concerned about abandoning the veneration of his people's traditional gods.[15] After completing his elementary education, Nyerere passed an entrance exam and began studying at a secondary school in Tabora.[15] Fellow pupils later remembered him as being ambitious and competitive, eager to come top of the class in examinations.[18] In 1942, Nyerere's father died,[19] having appointed his son Edward Wanzagi Nyerere as his successor.[20] Julius then decided to be baptised as a Roman Catholic.[15] In 1943, he completed his secondary education and decided to study at Makerere College in the Ugandan city of Kampala.[21] There, he decided to focus on philosophy, having been strongly influenced by the writings of the British philosopher John Stuart Mill.[21]

He began attending Government Primary School in Musoma at the age of 12 where he completed the four-year programme in three years and went on to Tabora Government School in 1937. He later described Tabora School as being "as close to Eton as you can get in Africa."[22] In 1943 he was baptised as a Catholic. He took the baptismal name of Julius, which eventually became his given name.[23][24] He received a scholarship to attend Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda. Here he founded the Tanganyika Welfare Association, which eventually merged with the Tanganyika African Association (TAA), which had been formed in 1929.[25] Nyerere received his teaching diploma in 1947.[6] He returned to Tanganyika and worked for 3 years at St. Mary's Secondary School in Tabora, where he taught Biology and English. In 1949, he received a government scholarship to attend the University of Edinburgh, where he earned an undergraduate Master of Arts degree in Economics and History in 1952. In Edinburgh he encountered Fabian thinking and began to develop his particular vision of connecting socialism with African communal living.[26][27]

Political career

TAA and TANU

On his return to Tanganyika, Nyerere took a position teaching History, English and Kiswahili, at St. Francis' College (currently Pugu secondary school), near Dar es Salaam.[27] In 1953 he was elected president of the Tanganyika African Association (TAA), a civic organisation dominated by civil servants, that he had been involved with while a student at Makerere University.[2] In 1954 he transformed TAA into the politically oriented Tanganyika African National Union (TANU).[2] TANU's main objective was to achieve national sovereignty for Tanganyika. A campaign to register new members was launched, and within a year TANU had become the leading political organisation in the country.[28][29] TANU had been founded in 1954 by Nyerere and Oscar Kambona.[30] By the late 1950s, TANU had extended its influence throughout the country and gained considerable support.[31]

Tanganyika Independence

In March 1955, Nyerere spoke before the UN Trusteeship Council for the first time, saying "with your help and with the help of the [British] Administering Authority we would be governing ourselves long before twenty to twenty-five years."[32] This seemed highly ambitious to everyone at the time.[32] Nyerere's activities attracted the attention of the Colonial authorities and he was forced to make a choice between his political activities and his teaching.[32] He was reported as saying that he was a "schoolmaster by choice and a politician by accident".[33] He resigned from teaching and travelled throughout the country speaking to common people and tribal chiefs, trying to garner support for movement towards independence. He also spoke on behalf of TANU to the Trusteeship Council and Fourth Committee of the United Nations in New York. His oratory skills and integrity helped Nyerere achieve TANU's goal for an independent country without war or bloodshed.

The cooperative British governor Sir Richard Turnbull aided the effort for independence. Nyerere entered the Colonial Legislative council following the country's first elections in 1958–59 and was elected chief minister following fresh elections in 1960 when Tanganyika was granted responsible government. On 9 December 1961, Tanganyika gained independence as a Commonwealth realm and Nyerere became its first Prime Minister. Tanganyika became a republic in 1962, though remaining in the Commonwealth of Nations, and Nyerere was elected as the country's first president. A month later, Nyerere declared that to further the interests of national unity and economic development, TANU was now the only legal political party. However, the country had effectively been a one-party state since independence. During the first years of his presidency, Nyerere used "preventive detention", allowed after his part passed the Preventive Detention Act, 1962, to eliminate trade unions and opposition political forces. He was reelected unopposed every five years until his retirement in 1985.

Unification of Tanzania

In 1964, Nyerere was instrumental in the union between the islands of Zanzibar and the mainland Tanganyika to form Tanzania with himself as president of the unified country. This was precipitated by the Zanzibar revolution on 12 January 1964 which toppled the Sultan of Zanzibar Jamshid bin Abdullah. The coup leader, a stonemason from Lira, Uganda, named John Okello, had intended Zanzibar to join Kenya. Nyerere, unnerved by a failed mutiny of the Tanganyika Rifles a few days later, ensured that Okello was barred from returning to Zanzibar after a visit to the mainland. In his absence the President of Zanzibar, Abeid Karume, negotiated with Nyerere on Zanzibar's behalf to enter into a union with Tanganyika to form the new country of Tanzania.[34]

Ujamaa and economic transformation

In January 196, Nyerere presented TANU's National Executive Committee with a new statement of party principles, the Arusha Declaration.[35] He followed this with a series of additional policy papers covering such areas as foreign policy and rural development.[35] After this point, the concept of socialism became central to the government's policy formation.[36]

When in power, Nyerere issued the Arusha Declaration, which called for the implementation of an economic programme influenced by African socialist ideas. He also established close ties with the People's Republic of China under Mao Zedong, and introduced a policy of collectivisation in the country's agricultural system, known as ujamaa, "socialism" in the sense of "familyhood" or "extended family"—the Swahili word for socialism comes from the word Jamaa—which literally mean "familyhood" and the "extended family".

In 1967, nationalisations transformed the government into the largest employer in the country. The state expanded rapidly into virtually every sector. It was involved in everything from retailing to import-export trade and even baking. This created an environment ripe for corruption.[37]

The private sector suffered from the multiplying cumbersome, bureaucratic procedures and excessive tax rates.[37] Enormous amounts of public funds were misappropriated and put to unproductive use.[37] Purchasing power declined at an unprecedented rate and even essential commodities became unavailable.[37] A system of state permits (vibali) required for many activities allowed officials to collect huge bribes in exchange for distributing the vibali.[37] Nyerere's policies laid a foundation for systemic corruption for years to come.[37] The ruling party's officials became known as Wabenzi ("people of the Benz"), referring to their taste for Benz cars.

Collectivization was accelerated in 1971. Because much of the population resisted collectivisation, Nyerere used his police and military forces to forcibly transfer much of the population into collective farms.[38][39] Houses were set on fire or demolished, sometimes with the family's pre-Ujamaa property inside.[39] The regime denied food to those who resisted.[39] A substantial amount of the country's wealth in the form of built structures and improved land (fields, fruit trees, fences) was destroyed or forcibly abandoned.[39] Livestock was lost or stolen, or fell ill or died.[39]

In 1975, the Tanzanian government issued the "ujamaa program" to send the Sonjo in northern Tanzania from compact sites with less water to flatter lands with more fertility and water; new villages were created to reap crops and raise livestock easier. This "villagization" (coined by W.M. Adams) encouraged the Sonjo to use modern irrigation techniques such as the 'unlined canals' and man-made springs (Adams 22–24). Given the diversion of water from the Kisangiro and Lelestutta Rivers by dams, river water can flow by canals into the irrigation systems to alleviate the hardships of smallholder farmers and livestock owners.[40]

Farming practices towards tea and cloves had increased for subsistence farmers. By 1974 ujaama programs and the IDA (International Development Association) worked hand in hand; while villagisation organized new villages to farm, the IDA financed projects to educate farmers to grow alternate crops and granted loans to farmers with added credit to small farmers (Whitaker 206). For example, only 3 tons of tea had been produced in 1964 yet by 1975, 2,100 tons of tea was the net output of smallholder farmers mostly by Nyerere's policies have given the communal villages the opportunity to grow tea leaves despite the long history of tea being only grown in estates (208). Although these statistics come from the late 1970s, one may understand agricultural growth through reorganising traditional farms and investing into non-staple agriculture (especially through educating farmers how to grow tea and improve farming methods. One may look upon another example of Tanzanian government's extensive services in training farmers to grow tobacco and improve farming methods, which aided significantly in tobacco yields 41.9 million pounds in 1975–1976. By 1976, Tanzania became the third-largest tobacco cultivator in Africa (207). Therefore, when the Tanzanian government used extensive services in agriculture, they achieved positive results and crop yields' growth, especially in tea and tobacco smallholder farming whose prices are cheaper for Tanzanian villages to consume than purchase products within the cities.[41]

As a result of this centralised government-controlled focus on tobacco and tea dominating arable land with only cash crops beneficial to the central government, food production plummeted, and only foreign aid prevented starvation. Tanzania, which had been the largest exporter of food in Africa and was always able to feed its people, became the largest importer of food in the continent.[42][43] Many sectors of the economy collapsed. There was a virtual breakdown in transportation. Goods such as toothpaste became virtually unobtainable.[42][43]

The deficit in cereal grains was more than 1 million tons between 1974 and 1977. Only loans and grants from the World Bank and the IMF in 1975 prevented Tanzania from going bankrupt. By 1979, ujamaa villages contained 90% of the rural population but only produced 5% of the national agricultural output.[44]

Nyerere announced that he would retire after presidential elections in 1985, leaving the country to enter its free market era — as imposed by structural adjustment under the IMF and World Bank – under the leadership of Ali Hassan Mwinyi, his hand-picked successor. Nyerere was instrumental in putting both Ali Hassan Mwinyi and Benjamin Mkapa in power. He remained the chairman of Chama Cha Mapinduzi (ruling party) for five years following his presidency until 1990, and is still recognised as the Father of the Nation.

Nyerere left Tanzania as one of the poorest, least developed, and most foreign aid-dependent countries in the world.[4] Nevertheless, Nyerere's government did much to foster social development in Tanzania during its time in office. At an international conference of the Arusha Declaration, Nyerere's successor Mwinyi noted the social gains of his predecessor's time in office: an increase in life expectancy to 52 years, a reduction in infant mortality to 137 per thousand, 2600 dispensaries, 150 hospitals, a literacy rate of 85%, two universities with over 4500 students, and 3.7 million children enrolled in primary school.[45]

Foreign policy

Nyerere's foreign policy emphasised nonalignment in the Cold War and under his leadership Tanzania enjoyed friendly relations with the People's Republic of China, the Soviet bloc as well as the Western world. Nyerere sided with the Chinese in the Sino-Soviet rivalry, and China reciprocated by its assistance with the building of the TAZARA Railway. When it was completed two years ahead of schedule, the TAZARA was the single longest railway in sub-Saharan Africa.[46] TAZARA was the largest single foreign-aid project undertaken by China at the time, at a construction cost of 500 million United States dollars (the equivalent of US $3.08 billion today).[47]

Nyerere signed his country to the British Commonwealth.[48]

Nyerere claimed Tanzania to be the first country to recognise Biafra soon after it declared independence from Nigeria in 1967, but was criticised for not consulting on this within his government first, as it could cause division in its relationship with Nigeria at the time.

Nyerere, along with several other Pan-Africanist leaders, founded the Organisation of African Unity in 1963, which he served as Chairperson of from 1984-1985. He signed the Lusaka Manifesto with Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia in 1969, affirming his opposition to white minority rule of African nations. Nyerere supported several militant groups active in white minority African states, including the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) of South Africa, FRELIMO when it sought to overthrow Portuguese rule in Mozambique, MPLA when it sought to overthrow Portuguese rule in Angola, and ZANLA in its war with the Smith government of Rhodesia. From the mid 1970s on, along with Kaunda, he was one of the leaders of the Front Line States which campaigned in support of black majority rule in southern Africa. In 1978 he led Tanzania in a successful war with Uganda, defeating and exiling the government of Idi Amin.

Nyerere was instrumental in the Seychelles military coup in 1977, in which soldiers trained by Nyerere deposed the country's democratically elected president James Mancham and installed a progressive one-party socialist state under France-Albert René.[49][50][51]

In an interview with Hubert Fichte from Frankfurter Rundschau, Nyerere commented that homosexuality was alien to Africa and therefore homosexuals cannot be defended against discrimination. His comments were omitted from the publication.[52] Despite it being illegal, persecution was rare during his tenure.[53]

He was criticised for his vindictive actions after unsuccessfully appealing to the Pan Africanist Congress to adopt dialogue and détente with Pretoria instead of armed revolution. He supported a leadership coup that installed David Sibeko but after Sibeko's assassination he crushed PAC resistance at Chunya Camp near Mbeya on 11 March 1980, when Tanzanian troops murdered and split up the PAC army into detention camps. Nyerere then pressured the Zimbabwe government to arrest and deport PAC personnel in May 1981. The PAC never recovered and despite rivalling the ANC from 1959–1981 quickly declined. Its Tanzanian controlled remnant under Clarence Makwetu gained only 1.2% in the 1994 South African election, the first after the end of apartheid.

Outside of Africa Nyerere was an inspiration to Walter Lini, Prime Minister of Vanuatu, whose theories on Melanesian socialism owed much to the ideas he found in Tanzania, which he visited. Lecturers inspired by Nyerere also taught at the University of Papua New Guinea in the 1980s, helping educated Melanesians familiarise themselves with his ideas.

In doing so, Nyerere—according to A. B. Assensoh—was "one of the few African leaders to have voluntarily, gracefully, and honourably bowed out" of governance.[54]

Post-presidential activity

After the Presidency, Nyerere remained the Chairman of Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) until 1990 when Ali Hassan Mwinyi took over. Nyerere remained vocal about the extent of corruption and corrupt officials during the Mwinyi administration. However, he raised no objections when the CCM abandoned its monopoly of power in 1992. He also served as Chairman of the independent International South Commission (1987–1990), and Chairman of the South Centre in the Geneva & Dar es Salaam Offices (1990–1999).

Nyerere did not leave the political arena altogether. He campaigned in support of the CCM candidates in Tanzania's 1995 presidential election.[54] He also took part in the fifth Pan-African Congress, held in the Ugandan city of Kampala.[55]

Nyerere retained enough influence to block Jakaya Kikwete's nomination for the presidency in the country's first multiparty elections in three decades, citing that he was too young to run a country. Nyerere was instrumental in getting Benjamin Mkapa elected (Mkapa had been Minister of Foreign Affairs for a time during Nyerere's administration). Kikwete later became president in 2005.

In one of his famous speeches during the CCM general assembly, Nyerere said in Swahili "Ninang'atuka", meaning that he was pulling out of politics for good. He kept to his word that Tanzania would be a democratic country. He moved back to his childhood home village of Butiama in northern Tanzania.[24] During his retirement, he continued to travel the world meeting various heads of government as an advocate for poor countries and especially the South Centre institution. Nyerere travelled more widely after retiring than he did when he was president of Tanzania. One of his last high-profile actions was as the chief mediator in the Burundi conflict in 1996.

The government and army contributed funds to build Nyerere a house in his home village; it was finished in 1999, although he only spent two weeks there prior to his death.[56]

Nyerere died in a London hospital of leukaemia on 14 October 1999.

In January 2005 the Catholic diocese of Musoma opened a case for the beatification of Julius Nyerere. Nyerere was a devout Catholic who attended Mass daily throughout his public life and was known for fasting frequently.

He received honorary degrees from the University of Edinburgh (UK), Duquesne University (USA), University of Cairo (Egypt), University of Nigeria (Nigeria), University of Ibadan (Nigeria), University of Liberia (Liberia), University of Toronto (Canada), Howard University (USA), Jawaharlal Nehru University (India), University of Havana (Cuba), National University of Lesotho,[57] University of the Philippines, Fort Hare University (South Africa), Sokoine University of Agriculture (Tanzania), and Lincoln University (PA, USA).

Cultural influences

Nyerere advocated for strict government control over popular culture in order to promote his vision of African pride and unity.[58] In the late 1960s, Nyerere criminalised "decadent" forms of culture including soul music, unapproved films and magazines, miniskirts, and tight trousers.[59][60]

Nyerere remained an influence upon the people of Tanzania in the years following his presidency. His broader ideas of socialism live on in the rap and hip hop tradition of Tanzania.[61] Nyerere believed socialism was an attitude of mind that countered discrimination and entailed equality of all human beings.[62] Therefore, ujamaa can be said to have created the social environment for the development of hip hop culture. As in other countries, hip hop emerged in post-colonial Tanzania when divisions among the population were prominent, whether by class, ethnicity or gender. Rappers broadcast messages of freedom, unity, and family, topics that are all reminiscent of the spirit Nyerere put forth in ujamaa.[61]

In addition, Nyerere supported the presence of foreign cultures in Tanzania saying, "a nation which refuses to learn from foreign cultures is nothing but a nation of idiots and lunatics...[but] to learn from other cultures does not mean we should abandon our own."[61]

Political ideology

Nyerere was an African nationalist,[48] and an African socialist.[63] He was also a Pan-Africanist.[64]

Nyerere took pains to avoid the claim that any particular tribal group influenced ujamaa.[65]

Personality and personal life

Nyerere was a modest man who was shy regarding the personality cult that followers established around him.[66]

When planners suggested infrastructure developments for his home area, Nyerere rejected the proposals, not wanting to present the appearance of giving favours to it.[8] Nyerere ensured that his parents' resting places were maintained.[67]

Honours and awards

Honours

| Order | Country | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |

Royal Order of the Seraphim | |

1963 |

| |

Order of José Marti[68] | |

1975 |

| |

Order of the Aztec Eagle (Collar)[69] | |

1975 |

| |

Amílcar Cabral Medal[69] | |

1976 |

| Order of Eduardo Mondlane[69] | |

1983 | |

| |

Order of Agostinho Neto[69] | |

1985 |

| |

Order of the Star of Ghana[70] | |

1988 |

| |

Order of the Companions of O. R. Tambo (Gold)[71] | |

2004 |

| Royal Order of Munhumutapa[72][73] | |

2005 | |

| |

Most Excellent Order of the Pearl of Africa (Grand Master)[74] | |

2005 |

| |

Order of Katonga[75] | |

2005 |

| |

National Liberation Medal[76] | |

2009 |

| |

Campaign Against Genocide Medal[76] | |

2009 |

| |

Order of the Most Ancient Welwitschia Mirabilis[77] | |

2010 |

| |

Order of Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere | |

2011 |

| |

National Order of the Republic (Grand Cordon)[78][79] | |

2012 |

| |

Order of Jamaica[80] | |

? |

Awards

- 1973: Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding[81]

- 1982: the Third World Prize

- 1983: Nansen Refugee Award

- 1986: Sir Seretse Khama SADC Medal

- 1987: Lenin Peace Prize

- 1988: Joliot-Curie Medal of Peace

- 1992: International Simón Bolívar Prize

- 1995: Gandhi Peace Prize

Posthumous:

- 2000: Statesman of the 20th century by the Chama cha Mapinduzi

- 2009: World Hero of Social Justice by the 63rd President of UNGA, Miguel d'Escoto Brockmann[82]

- 2011: Tanzania Professional Network Award[83]

Reception and legacy

Nyerere was remembered "in African nationalist history as an uncompromising socialist".[84] He published widely over the course of his life.[85] He gained recognition for the successful merger between Tanganyika and Zanzibar.[86]

Bureaucrats from TANU subsequently established a cult of personality around Nyerere.[87] Posthumously, the Catholic Church of Tanzania began the processing of beatifying Nyerere, hoping to have him recognised as a saint.[87]

After his death, Nyerere received far less attention than other, contemporary African leaders like Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, and Nelson Mandela.[87] Much of the literature published on Nyerere has been in-critical and hagiographic.[88]

In 2009 his life was portrayed in Imruh Bakari's – The Legacy of Julius Kambarage Nyerere (Mnet, Great Africans Series, 2009).[89]

Eponyms

- Julius Nyerere International Airport, (renamed from Dar es Salaam International Airport in 2005) the nation's largest and busiest airport

- Julius Nyerere International Convention Centre, an ultramodern conference centre in Dar es Salaam with a seating capacity for about 1,000 people

- Julius Nyerere University of Agriculture, a proposed university in his hometown of Butiama

- Julius Nyerere University of Kankan, in Kankan, Guinea

- Nyerere Day, a public holiday in Tanzania (14 October)

- Nyerere Cup

- The Julius Nyerere Peace and Security Building of the Commission of the African Union (AU) in Addis Ababa[90]

- Nyerereite, a rare sodium calcium carbonate mineral. Formula: Na2Ca(C O3)2

- Order of Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere, an order of Tanzania

- Roads and streets:

Botswana: Nyerere Drive, Gaborone (1.6 km)

Botswana: Nyerere Drive, Gaborone (1.6 km) Kenya: Nyerere Road, Nairobi (0.75 km)

Kenya: Nyerere Road, Nairobi (0.75 km) Kenya: Nyerere Avenue, Mombasa (1.5 km)

Kenya: Nyerere Avenue, Mombasa (1.5 km) Kenya: Nyerere Road, Kisumu (2 km)

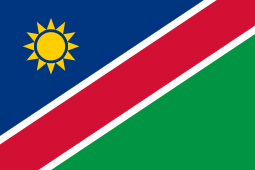

Kenya: Nyerere Road, Kisumu (2 km) Namibia: Julius Nyerere Street, Windhoek (1.1 km)

Namibia: Julius Nyerere Street, Windhoek (1.1 km) South Africa: Julius Nyerere Street, Durban (0.5 km)

South Africa: Julius Nyerere Street, Durban (0.5 km) Tanzania: Nyerere Road, Mwanza (0.8 km)

Tanzania: Nyerere Road, Mwanza (0.8 km) Tanzania: Nyerere Cable-Stayed Bridge, Dar Es Salaam (0.687 km)

Tanzania: Nyerere Cable-Stayed Bridge, Dar Es Salaam (0.687 km) Tanzania: Nyerere Road, Unguja, Zanzibar (6.5 km)

Tanzania: Nyerere Road, Unguja, Zanzibar (6.5 km) Zambia: Nyerere Road, Kitwe (1.4 km)

Zambia: Nyerere Road, Kitwe (1.4 km) Zimbabwe: Julius Nyerere Way, Harare (1 km)

Zimbabwe: Julius Nyerere Way, Harare (1 km)

- Schools in Tanzania:

- Nyerere Secondary School in Mwanga District and J.K. Nyerere Secondary School in Moshi, Kilimanjaro Region

- Mwalimu J. K. Nyerere Secondary School in Mbozi District, Mbeya Region

- Nyerere Memorial School in Korogwe, Tanga Region

- Nyerere High School Migoli in Iringa Region

- Nyerere Secondary School in Unguja, Zanzibar

- The University of Edinburgh awards a Julius Nyerere Scholarship for Masters students from Tanzania[91]

- The African Union Commission runs The Nyerere Program for implementing scholarships and academic mobility initiatives[92]

Memorials

Publications

- Freedom and Unity (Uhuru na Umoja): A Selection from Writings & Speeches, 1952–1965 (Oxford University Press, 1967)

- Freedom and Socialism (Uhuru na Ujama): A Selection from Writings & Speeches, 1965–1967 (Oxford University Press, 1968)

- Includes "The Arusha Declaration"; "Education for self-reliance"; "The varied paths to socialism"; "The purpose is man"; and "Socialism and development."

- Freedom and Development (Uhuru Na Maendeleo): A Selection from the Writings & Speeches, 1968–73 (Oxford University Press, 1974)

- Includes essays on adult education; freedom and development; relevance; and ten years after independence.

- Ujamaa – Essays on Socialism (1977)

- Crusade for Liberation (1979)

- Julius Kaisari (a Swahili translation of William Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar, as a gift to the nation to celebrate its first anniversary of independence.)

- Mabepari wa Venisi (a Swahili translation of William Shakespeare's play – The Merchant of Venice)

- Utenzi wa Enjili Kadiri ya Utungo wa Mathayo (a poetic Swahili version of the Gospel of Matthew)

- Utenzi wa Enjili Kadiri ya Utungo wa Marko (a poetic Swahili version of the Gospel of Mark)

- Utenzi wa Enjili Kadiri ya Utungo wa Luka (a poetic Swahili version of the Gospel of Luke)

- Utenzi wa Enjili Kadiri ya Utungo wa Yohana (a poetic Swahili version of the Gospel of John)

- Utenzi wa Matendo ya Mitume (a poetic Swahili version of the Acts of the Apostles)

See also

References

- ↑ "Obituary: Julius Nyerere". The Daily Telegraph. London. 15 October 1999. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 Blumberg, Arnold (1995). Great Leaders, Great Tyrants?: Contemporary Views of World Rulers who Made History. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 221–222. ISBN 0-313-28751-1.

- ↑ Hopkins, Raymond F. (1971). Political Roles in a New State: Tanzania's First Decade. Yale University Press. p. 204. ISBN 0-300-01410-4.

- 1 2 Skinner, Annabel (2005). Tanzania & Zanzibar. New Holland Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 1-86011-216-1.

- ↑ http://www.policyforum-tz.org/files/LeeKyongKoo.pdf

- 1 2 3 Simon, David (2006). Fifty key thinkers on development. Taylor & Francis. p. 193. ISBN 0-415-33790-9.

- ↑ Molony 2014, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 Molony 2014, p. 12.

- ↑ Clagett Taylor, James (1963). The political development of Tanganyika. Stanford University Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-8047-0147-4.

- 1 2 Molony 2014, p. 32.

- ↑ Molony 2014, p. 33.

- ↑ Molony 2014, pp. 13, 34.

- ↑ Molony 2014, p. 34.

- ↑ Molony 2014, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Assensoh 1998, p. 125.

- ↑ Molony 2014, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Molony 2014, p. 35.

- ↑ Assensoh 1998, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Assensoh 1998, p. 125; Molony 2014, p. 13.

- ↑ Molony 2014, p. 36.

- 1 2 Assensoh 1998, p. 126.

- ↑ Lawrence, David (2009). Tanzania: The Land, Its People and Contemporary Life. Godfrey Mwakikagile. p. 58. ISBN 9987-9308-3-2.

- ↑ Kantowicz, Edward R. (2000). Coming Apart, Coming Together. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 258. ISBN 0-8028-4456-1.

- 1 2 Kaufman, Michael T. (15 October 1999), "Julius Nyerere of Tanzania Dies; Preached African Socialism to the World", The New York Times, retrieved 26 March 2010

- ↑ Mwakikagile, Godfrey (2006). Tanzania Under Mwalimu Nyerere: Reflections on an African Statesman. Godfrey Mwakikagile. p. 21. ISBN 0-9802534-9-7.

- ↑ Adi, Hakim; Sherwood, Marika (2003). "Julius Kambarage Nyerere". Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa and the Diaspora Since 1787. Routledge. p. 147. ISBN 0-203-41780-1.

- 1 2 van Dijk, Ruud (2008). Encyclopedia of the Cold War, Volume 1. Taylor & Francis. p. 880. ISBN 0-415-97515-8.

- ↑ Kangsen, Muna (13 April 2007), "Happy Birthday Mwalimu", Daily News, Daily News Media Group, archived from the original on 27 September 2007, retrieved 21 March 2010

- ↑ "Julius Nyerere". Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- ↑ Pratt 1976, pp. 22, 23.

- ↑ Pratt 1976, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Bjerk, P. (2015). Building a Peaceful Nation: Julius Nyerere and the Establishment of Sovereignty in Tanzania, 1960-1964. Rochester studies in African history and the diaspora. University of Rochester Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-58046-505-2. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ↑ Marshall, Julian (15 October 1999), "Julius Nyerere", The Guardian, Guardian Media Group, retrieved 30 March 2010

- ↑ Conley, Robert (27 April 1964), "Tanganyika gets new rule today", New York Times, p. 11

- 1 2 Pratt 1976, p. 4.

- ↑ Pratt 1976, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rick Stapenhurst, Sahr John Kpundeh. Curbing corruption: toward a model for building national integrity. pp. 153–156.

- ↑ Skinner, Annabel (2005). Tanzania & Zanzibar. New Holland Publishers. p. 18. ISBN 1-86011-216-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Philip Wayland Porter. Challenging nature: local knowledge, agroscience, and food security in Tanga.

- ↑ W.M. Adams, T. Potkanski and J.E.G. Sutton (1994). "Indigenous Farmer-Managed Irrigation in Sonjo, Tanzania". The Geographical Journal. Vol. 160. No. 1 (March 1994). pp. 17–32. Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers).

- ↑ Donald P. Whitaker (1978). "The Economy", Tanzania: A Country Study. American University. Washington DC.

- 1 2 Blair, David (10 May 2006), "Africa in a nutshell", The Daily Telegraph

- 1 2 Lessons from Socialist Tanzania. Sven Rydenfelt. The Freeman. September 1986, Volume: 36, Issue: 9.

- ↑ Meredith, Martin (2006). The fate of Africa: from the hopes of freedom to the heart of despair : a history of fifty years of independence. Public Affairs. ISBN 1-58648-398-6.

- ↑ Mastering Modern World History by Norman Lowe

- ↑ Deborah Brautigam (7 April 2011). The Dragon's Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa. OUP Oxford. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-19-161976-2.

- ↑ "Historical Milestones". Tanzania Zambia Railway Authority.

- 1 2 Assensoh 1998, p. 26.

- ↑ Military power and politics in black Africa. Simon Baynham. p. 181

- ↑ Leonard, Thomas M. (2006). Encyclopedia of the Developing World, Volume 1. Taylor & Francis. p. 1402. ISBN 0-415-97662-6.

- ↑ Cawthra, Gavin; Du Pisani, André; Omari, Abillah H. (2007). Security and Democracy in Southern Africa. IDRC. p. 143. ISBN 1-86814-453-4.

- ↑ Chris Dunton; Mai Palmberg (1996). Human Rights and Homosexuality in Southern Africa. Nordic Africa Institute. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-91-7106-402-8.

- ↑ Michael Lynch (12 April 2013). Access to History for the IB Diploma: Origins and development of authoritarian and single-party states. Hodder Education. pp. 395–. ISBN 978-1-4441-5646-1.

- 1 2 Assensoh 1998, p. 29.

- ↑ Assensoh 1998, p. 149.

- ↑ Molony 2014, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ "Historical Note of the National University of Lesotho", National University of Lesotho, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 26 April 2010

- ↑ Lemelle, S.J. (2006). "'Ni Wapi Tunakwenda': Hip hop culture and the children of Arusha". In Basu, D.; Lemelle, S.J. The vinyl ain't final: Hip hop and the globalization of black popular culture. Pluto. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-7453-1941-4. Retrieved 5 July 2017. Missing

|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Allma, Jean Marie. Fashioning Africa: power and the politics of dress. p. 108.

- ↑ Skinner, Annabel (2005). Tanzania & Zanzibar. New Holland Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 1-86011-216-1.

- 1 2 3 Lemelle, Sidney J. (2006). "'Ni wapi Tunakwenda': Hip Hop Culture and the Children of Arusha". In Dipannita, Basu; Sidney J., Lemelle. The vinyl ain't final: hip hop and the globalization of black popular culture. Pluto Press. pp. 230–254. ISBN 0-7453-1940-8.

- ↑ Keregero, Keregero (14 October 2005), "Mwalimu Julius Nyerere on Socialism", The Guardian, IPP Media, archived from the original on 22 February 2006, retrieved 21 March 2010

- ↑ Assensoh 1998, p. 25.

- ↑ Assensoh 1998, p. 27.

- ↑ Molony 2014, p. 21.

- ↑ Molony 2014, p. 7.

- ↑ Molony 2014, p. 14.

- ↑ Condecorado Julius K. Nyerere por el Gobierno Revolucionario con la Orden Nacional Jose Marti LANIC [LATIN AMERICAN NETWORK INFORMATION CENTER] (Granma) (in Spanish)

- 1 2 3 4 Awards / Prices Juliusnyerere.info

- ↑ Dr. Obed Yao Asamoah (20 October 2014). The Political History of Ghana (1950-2013): The Experience of a Non-Conformist. AuthorHouse. pp. 439–. ISBN 978-1-4969-8563-7.

- ↑ "Government Gazette" (PDF). info.gov.za. 11 June 2004. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ Maura Mwingira (18 April 2005). "Nyerere awarded Zimbabwe's highest medal". Kafoi.com (Daily News). Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ↑ "The Royal Order of Munhumutapa". SADC Today. 4 October 2005. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ John Musinguzi (24 February 2013). "Understanding Museveni's medals". The Observer (Uganda). Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ↑ "Museveni honours Nyerere". New Vision. 10 July 2007. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- 1 2 Daniel R. Kasule (3 July 2009). "Museveni, Zenawi, Nyerere to receive national honours". The New Times. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ↑ Tanganyika: Africa’s mecca for liberation movements at the Wayback Machine (archived 16 May 2013) Archived from the original on 16 May 2013

- ↑ "Burundi: Decree of July 2012" (PDF). burundi-gov.bi. 1 July 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ↑ "Museveni gets prestigious Burundi award". New Vision. 4 July 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ "Members of the Order of Jamaica (Deceased)". Government of Jamaica. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "List of the recipients of the Jawharlal Nehru Award". Indian Council for Cultural Relations. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ↑ "Morales Named "World Hero of Mother Earth" by UN General Assembly". Latin American Herald Tribune. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ↑ "Kikwete urges local experts to embrace integrity". Daily News. Tanzania. 4 December 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ Assensoh 1998, p. 5.

- ↑ Assensoh 1998, p. 24.

- ↑ Assensoh 1998, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 Molony 2014, p. 2.

- ↑ Molony 2014, p. 1.

- ↑ "Mwalimu: The Legacy of Julius Kambarage Nyerere (2009) - The List". film.list.co.uk.

- ↑ Kebede, Abraham. "Inauguration of the Julius Nyerere Peace and Security Building-African Union". African Union Peace and Security Department.

- ↑ "The Julius Nyerere Masters Scholarships - The University of Edinburgh". www.ed.ac.uk.

- ↑ "Education Division - African Union". www.au.int.

- Yakan, Mohamad A (1999). Almanac of African Peoples & Nations. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-433-9.

- Smith, Mark K. "Julius Nyerere, lifelong learning and informal education." The Encyclopaedia of Informal Education. 1998.

- Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere, profile at Embassy of Tanzania, Sweden

- Former Presidents: Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere, Tanzania State House

- Godfrey Mwakikagile Life under Nyerere, First Edition, New Africa Press, ISBN 978-0-9802587-2-1.

- Bjerk, Paul (2015). Building a Peaceful Nation: Julius Nyerere and the Establishment of Sovereignty in Tanzania, 1960-1964. Rochester University Press. ISBN 9781580465052

Sources

- Assensoh, A. B. (1998). African Political Leadership: Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, and Julius K. Nyerere. Malabar, Florida: Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 9780894649110.

- Molony, Thomas (2014). Nyerere: The Early Years. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell and Brewer. ISBN 978-1847010902.

- Pratt, Cranford (1976). The Critical Phase in Tanzania 1945–1968: Nyerere and the Emergence of a Socialist Strategy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20824-6.

External links

- Nyerere's remarks on Ali Hassan Mwinyi Corrupt practices

- PBS Interview with Nyerere on the Great Lakes crisis, December 26, 1996

- Infed.org article on Nyerere and his views on education in Tanzania

- Jerry Atkin's Nyerere tribute, from InMotion Magazine

- SouthCentre Nyerere Memorial Site

- A translation of Merchant of Venice into KiSwahili

- Nyerere Obituary from the ANC

- NPR Weekend Edition reflection on Nyerere

- Julius Nyerere Fellowship

- Called to greatness MercatorNet, 10 November 2006

- Beatification inquiry for Tanzania's Nyerere (from Catholic World News)

- Is Nyerere's process to sainthood timely? (from IPP Media)

- The Julius Nyerere Intellectual Festival Week by Gacheke Gachihi, All Africa, 11 June 2009

- The Julius Nyerere Master's Scholarships (University of Edinburgh)