Julian of Norwich

| Julian of Norwich | |

|---|---|

Julian of Norwich, as depicted in the church of Ss Andrew and Mary, Langham, Norfolk | |

| Anchoress, Mystic | |

| Born |

c. 8 November 1342 Norfolk |

| Died |

c. 1416 (aged 73–74) Norwich |

| Venerated in |

Anglican Communion Lutheran Church |

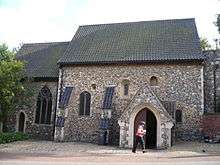

| Major shrine | Church of St Julian, Norwich |

| Feast | 8 May or 13 May |

| Major works | Revelations of Divine Love |

Julian of Norwich (c. 8 November 1342 – c. 1416) was an English anchoress and an important Christian mystic and theologian. Her Revelations of Divine Love, written around 1395, is the first book in the English language known to have been written by a woman. Julian was also known as a spiritual authority within her community, where she also served as a counsellor and advisor.[1] She is venerated in the Anglican and Lutheran churches. The Roman Catholic Church has not declared her to be a saint or given her the title Blessed. Accordingly, she does not appear in the Roman Martyrology, nor is she included in the calendar of the Catholic Church in England and Wales.[2][3]

Personal life

Very little is known about Julian's life. Even her name is uncertain; the name 'Julian' is generally thought to have been derived from the Church of St Julian in Norwich, to which her anchorite's cell was joined.[4] 'Julian' was, however, a common name among women in the Middle Ages and could possibly have belonged to the anchoress as well as to the church.[4]

Julian's writings indicate that she was probably born around 1342 and died around 1416.[5][6] She may have been from a privileged family residing in or near Norwich, at the time the second largest city in England. At least one source considered it likely that she received her early education with the Benedictine nuns at nearby Carrow.[7]

Plague epidemics were rampant during the 14th century and, according to some scholars, Julian may have become an anchoress unmarried or, having lost her family in the plague, as a widow.[8] Becoming an anchoress may have served as a way to quarantine her from the rest of the population. There is scholarly debate as to whether Julian was a nun in a nearby convent or a laywoman.[8]

When she was 30 and living at home, Julian suffered from a serious illness. Since she was presumed to be near death, her curate came to administer the last rites of the Catholic Church on 8 May 1373. As part of the ritual, he held a crucifix in the air above the foot of her bed. Julian reported that she was losing her sight and felt physically numb, but as she gazed on the crucifix she saw the figure of Jesus begin to bleed. Over the next several hours, she had a series of sixteen visions of Jesus Christ, which ended by the time she recovered from her illness on 13 May 1373.[9][10] Julian wrote about her visions immediately after they had happened (although the text may not have been finished for some years), in a version of the Revelations of Divine Love now known as the Short Text; this narrative of 25 chapters is about 11,000 words long.[11][12]

Twenty to thirty years later, perhaps in the early 1390s, Julian began to write a theological exploration of the meaning of the visions, known as The Long Text, which consists of 86 chapters and about 63,500 words.[13] This work seems to have gone through many revisions before it was finished, perhaps in the 1410s or even the 1420s.[11]

The English mystic Margery Kempe, who was the author of the first known autobiography written in England, mentioned going to Norwich to speak with her in around 1414.[14]

Adam Easton's Defense of St Birgitta, Alfonso of Jaen's Epistola Solitarii, and William Flete's Remedies against Temptations, are all referred to in Julian's text.[15]

Revelations of Divine Love

The Short Text survives in only one manuscript, the mid-15th century Amherst Manuscript, which was copied from an original written in 1413 in Julian’s lifetime.[16] The Short Text does not appear to have been widely read and was not edited until 1911.[17]

The Long Text appears to have been slightly better known, but still does not seem to have been widely circulated in late medieval England. The one surviving manuscript from this period is the mid- to late-15th century Westminster Manuscript, which contains a portion of the Long Text (not naming Julian as its author), refashioned as a didactic treatise on contemplation.[18] The surviving manuscripts of the whole Long Text fall into two groups, with slightly different readings. On the one hand, there exists the late 16th century Brigittine Long Text manuscript, produced in exile in the Antwerp region and now known as the Paris Manuscript. The other set of readings may be found in two manuscripts, now in the British Library's Sloane Collection.[19] It is believed these nuns had an original, perhaps a holograph, manuscript of the Long Text written in Julian's Norwich dialect,[19] which was written out and preserved in the Cambrai and Paris houses of the English Benedictine nuns in exile in the mid-17th century.[20]

The first printed version of the Revelations was edited by a Benedictine, Serenus Cressy, in 1670. It was reprinted in 1843, 1864 and again in 1902. Modern interest in the text increased with the 1877 publication of a new edition of the Long Text by Henry Collins. An important moment was the publication of Grace Warrack's 1901 version of the book, with its "sympathetic informed introduction" and modernised language, which introduced most early 20th century readers to Julian's writings.[21] Following the publication of the Warrack edition, Julian's name spread rapidly and she became a topic in many lectures and writings. Many editions of the works have been published in the last forty years (see below for further details), with translations into French (five times), German (four times), Italian, Finnish, Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, Dutch, Catalan, Greek and Russian.[18]

Revelations is a celebrated work in Roman Catholicism and Anglicanism because of the clarity and depth of Julian's visions of God.[22] Julian of Norwich is now recognised as one of England's most important mystics.[23]

Theology

For Denys Turner the core issue Julian addresses in Revelations of Divine Love is "the problem of sin". Julian says that sin is "behovely", which is often translated as "necessary", "expedient", or "appropriate". A more nuanced reading relates it to the scholastics "conveniens" or "fitting".[7][24]

Julian came to such a sense of the awfulness of sin that she reckoned the pains of hell are to be chosen in preference to it. "And to me was shown no harder hell than sin. For a kind soul has no hell but sin."[25] Julian believed that sin was necessary because it brings people to self-knowledge, which leads to acceptance of the role of God in their life.[26] Julian describes how God suffers with his creation as it experiences great and multifaceted evil.[27]

Julian lived in a time of turmoil, but her theology was optimistic and spoke of God's omnibenevolence and love in terms of joy and compassion. Revelations of Divine Love "contains a message of optimism based on the certainty of being loved by God and of being protected by his Providence."[28]

The most characteristic element of her mystical theology was a daring likening of divine love to motherly love, a theme found in the Biblical prophets, as in Isaiah 49:15.[28][29] According to Julian, God is both our mother and our father. As Caroline Walker Bynum showed, this idea was also developed by Bernard of Clairvaux and others from the 12th century onward.[30] Some scholars think this is a metaphor rather than a literal belief. In her fourteenth revelation, Julian writes of the Trinity in domestic terms, comparing Jesus to a mother who is wise, loving and merciful. F. Beer asserted that Julian believed that the maternal aspect of Christ was literal and not metaphoric: Christ is not like a mother, he is literally the mother.[31] Julian emphasized this by explaining how the bond between mother and child is the only earthly relationship that comes close to the relationship a person can have with Jesus.[32] She also wrote metaphorically of Jesus in connection with conception, nursing, labour, and upbringing, but saw him as our brother as well.

She wrote, "For I saw no wrath except on man's side, and He forgives that in us, for wrath is nothing else but a perversity and an opposition to peace and to love."[33] She wrote that God sees us as perfect and waits for the day when human souls mature so that evil and sin will no longer hinder us.[34]

Although Julian's views were not typical, the authorities might not have challenged her theology because of her status as an anchoress. A lack of references to her work during her own time may indicate that the religious authorities did not count her worthy of refuting, since she was an obscure woman.

Legacy

Julian's feast day in the Roman Catholic tradition is on 13 May.[35] Her feast day is on 8 May in the Anglican[8] and Lutheran traditions.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church quotes Julian of Norwich when it explains the Catholic viewpoint that, in the mysterious designs of Providence, God can draw a greater good even from evil:[28] "Here I was taught by the grace of God that I should steadfastly keep me in the faith... and that at the same time I should take my stand on and earnestly believe in what our Lord shewed in this time—that 'all manner [of] thing shall be well.'"[36]

Poet T. S. Eliot incorporated the saying that "…All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well", as well as Julian's "the ground of our beseeching" from the 14th Revelation, into Little Gidding, the fourth of his Four Quartets:[37]

In 1981 Sydney Carter wrote the song "Julian of Norwich" (sometimes called "The Bells of Norwich"), based on words of Julian.

The University of East Anglia honoured Julian in 2013 by naming the new study centre (with a 280-seat lecture theatre, seminar rooms, and adherence to high ecological standards) the "Julian Study Centre".[38]

Each year, beginning in 2013, there has been a week-long celebration of Julian of Norwich in her home city of Norwich, England. With concerts, lectures, workshops, and tours, the week aims to educate all interested people about Julian of Norwich, presenting her as a cultural, historical, literary, spiritual, and religious figure of international significance.

In recent decades a number of new editions, and renderings into modern English, of her Revelations of Divine Love, have appeared, as well as publications about her. The revival of interest in her has been associated with a renewed interest in the English-speaking world in Christian contemplation. One association of contemplative prayer groups, The Julian Meetings, is named after her.

See also

References

- ↑ "Juliana of Norwich -". www.projectcontinua.org. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- ↑ Martyrologium Romanum. Typis Vaticanis. 2004.

- ↑ "Liturgy Office of England and Wales, Calendar 2017". www.liturgyoffice.org.uk. Retrieved 2017-02-20.

- 1 2 Groves, Nicholas (2010). The Medieval Churches of the City of Norwich. Norwich: Norwich Heritage Economic and Regeneration Trust (HEART) and East Publishing. p. 74.

- ↑ Ritchie, Ronald, Joy, Kate (2001). Available Means: An Anthology of Women's Rhetoric. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 25–28.

- ↑ Beer, F., Women and Mystical Experience in the Middle Ages, p. 130. Boydell Press, 1992.

- 1 2 Watson, Nicholas and Jenkins, Jacqueline. The Writings of Julian of Norwich, Penn State Press, 2006 ISBN 9780271029085

- 1 2 3 Bhattacharji, Santha. "Julian of Norwich (1342 – c. 1416)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online Ed. Oxford: OUP. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ The Broadview Anthology of British Literature. Toronto, Canada: Broadview Press. 2011. p. 348.

- ↑ "Julian of Norwich". Encyclopædia Britannica Profiles. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 June 2006.

- 1 2 Bernard McGinn, The Varieties of Vernacular Mysticism, (New York: Herder & Herder, 2012), p. 425.

- ↑ Julian of Norwich. Showings. Paulist Press. 1978.

- ↑ Jantzen, G. Julian of Norwich: Mystic and Theologian, pp. 4–5. Paulist Press, 1988.

- ↑ "The Book of Margery Kempe, Book I, Part I". The Book of Margery Kempe. TEAMS Middle English Texts. 1996. Retrieved 19 August 2007.

- ↑ Julia Bolton Holloway, Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of Norwich and Adam Easton, OSB, Analecta Cartusiana, 2008.

- ↑ The manuscript is now in the British Library.

- ↑ McGinn, p. 425.

- 1 2 Bernard McGinn, The Varieties of Vernacular Mysticism, (New York: Herder & Herder, 2012), p. 426.

- 1 2 Crampton. The Shewings of Julian of Norwich, p. 17. Western Michigan University, 1993.

- ↑ All the Julian manuscripts have been edited by Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton Holloway in their 2001 edition (Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo).

- ↑ Crampton, p. 18.

- ↑ "Julian of Norwich". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ Pelphrey, B. Christ Our Mother: Julian of Norwich, p. 14. Michael Glazier Inc., 1989.

- ↑ Turner, Denys. Julian of Norwich, Theologian, Yale University Press, 2011 ISBN 9780300164688

- ↑ Graves, Dan. "All Will Be Well", Christian History Institute

- ↑ Beer, pg. 143.

- ↑ Perrine, Tim. "Revelations of Divine Love", CCEL

- 1 2 3 Pope Benedict XVI. General Audience, December 1, 2010

- ↑ Isaiah 49:15, NAB

- ↑ Bynum, Caroline Walker (1982). Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages. Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Beer, p. 152.

- ↑ Beer, p. 155.

- ↑ Revelations of Divine Love, p. 45. ed., D. S. Brewer, 1998

- ↑ Revelations of Divine Love, p. 50. D. S. Brewer, 1998

- ↑ Online, Catholic. "St. Juliana of Norwich - Saints & Angels - Catholic Online". Catholic Online. Retrieved 2016-12-30.

- ↑ "Divine Providence", Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed., §313, Libreria Editrice Vaticana

- ↑ Newman, Barbara (2011). "Eliot's Affirmative Way: Julian of Norwich, Charles Williams, and Little Gidding". Modern Philology. 108: 427–61. JSTOR 10.1086/658355. doi:10.1086/658355.

- ↑ University of East Anglia

Modern editions and translations

Editions:

- The Writings of Julian of Norwich, ed. Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins. Penn State University Press, 2006. (An edition and commentary of both the Short Text and Long Text. The Long Text is here generally based on the Paris manuscript)

- Denise N. Baker (2005), of the Long Text, based on the Paris manuscript

- Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translation, ed. Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P., and Julia Bolton Holloway. Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2001. ISBN 88-8450-095-8. [A “quasi-fascimile” of each version of the Showing of Love in the Westminster, Paris, Sloane and Amherst Manuscripts.]

- The Shewings of Julian of Norwich, ed. Georgia Crampton. (Kalamazoo, MI: Western Michigan University, 1994). [Of the Long Text, based largely on one of the two Sloane manuscripts.]

- Colledge, Edmund, and James Walsh, Julian of Norwich: Showings, Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1978. (a fully annotated edition of both the Short Text and Long Text, basing the latter on the Paris manuscript but using alternative readings from the Sloane manuscript when these were judged to be superior)

Translations:

- Fr. John-Julian, "The Complete Julian of Norwich". Orleans, MA; Paraclete Press, 2009

- Dutton, Elisabeth. A Revelation of Love (Introduced, Edited & Modernized). Rowman & Littlefield, 2008

- Showing of Love, Trans. Julia Bolton Holloway. Collegeville: Liturgical Press; London; Darton, Longman and Todd, 2003. [Collates all the extant manuscript texts]

- Wolters, Clifton, Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love, (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966) (the Long Text, based on the Sloane manuscripts)

Sources

- Beer, F., Women and Mystical Experience in the Middle Ages, Boydell Press, 1992

- Crampton, Georgia. The Shewings of Julian of Norwich, Western Michigan University, 1993

- Hick, John. The Fifth Dimension: An Exploration of the Spiritual Realm, Oxford: One World, 2004

- McGinn, Bernard. The Varieties of Vernacular Mysticism, New York: Herder & Herder, 2012

Bibliography

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Dutton, E.M. (2008). Julian of Norwich: The Influence of Late-medieval Devotional Compilations. Boydell & Brewer.

- Holloway, J.B., Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of Norwich and Adam Easton, O.S.B., Analecta Cartusiana, 2008; ISBN 978-3-902649-01-0.

- Holloway, J.B., Julian among the Books: Julian of Norwich's Theological Library, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4438-8894-3.

- Jantzen, Grace. Julian of Norwich: Mystic and Theologian. London: SPCK. 1987.

- McAvoy, L. H., ed., A Companion to Julian of Norwich, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2008.

- McEntire, S., ed., Julian of Norwich: A Book of Essays, Taylor & Francis, 1998.

- Turner, D., Julian of Norwich, Theologian, Yale University Press, 2011

- Nicholas Watson (1992). "The Trinitarian Hermeneutic in Julian of Norwich's Revelation of Love". In Glasscoe, M. The Medieval Mystical Tradition in England V: Papers read at Dartington Hall, July 1992. D.S. Brewer. pp. 79–100.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Julian of Norwich |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Julian of Norwich. |

- "Juliana of Norwich", Catholic Encyclopedia

- The Julian Centre, a bookshop and information centre, next door to St Julian’s Church in Norwich.

- "Julian of Norwich", Luminarium Website, Life, works, essays

- "Julian of Norwich", Umilta Website, Life, manuscripts, texts and contexts

- Revelations of Divine Love at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Julian of Norwich at Internet Archive

- Works by Julian of Norwich at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)