Josiah

| Josiah | |

|---|---|

| King of Judah | |

| |

| Reign | 640 to 609 BCE |

| Predecessor | Amon of Judah |

| Successor | Jehoahaz of Judah |

| Born |

c. 648 BCE probably Jerusalem |

| Died |

Tammuz (June/July) 609 BCE Jerusalem |

| Spouse |

Zebudah Hamutal |

| Issue |

Johanan Jehoiakim Jehoahaz Zedekiah |

| House | House of David |

| Father | Amon |

| Mother | Jedidah |

Josiah or Yoshiyahu (/dʒoʊˈsaɪ.ə/ or /dʒəˈzaɪ.ə/;[1][2] Hebrew: יֹאשִׁיָּהוּ, Modern Yoshiyyáhu, Tiberian Yôšiyyāhû, literally meaning "healed by Yah" or "supported of Yah"; Latin: Iosias; c. 649–609 BCE) was a king of Judah (641–609 BCE), who according to the Hebrew Bible, instituted major religious changes. Josiah is credited by most historians with having established or compiled important Hebrew Scriptures during the "Deuteronomic reform" that occurred during his rule.

Josiah became king of Judah at the age of eight, after the assassination of his father, King Amon, and reigned for thirty-one years, from 641/640 to 610/609 BCE.[3] He is described as a very righteous king, a king who "walked in all the way of David his father, and turned not aside to the right hand or to the left" (2 Kings 22:2).

He is also one of the kings mentioned in one of the two divergent genealogies of Jesus in the New Testament.

Family

| Rulers of Judah |

|---|

Josiah is known only from biblical texts. No reference to him exists in surviving texts of the period from Egypt or Babylon, and no clear archaeological evidence, such as inscriptions bearing his name, has ever been found.[4]

According to the Bible, Josiah was the son of King Amon and Jedidah, the daughter of Adaiah of Bozkath.[5] His grandfather Manasseh was one of the kings blamed for turning away from the worship of Yahweh. Manasseh adapted the Temple for idolatrous worship. Josiah's great-grandfather was King Hezekiah, a noted reformer.

Josiah had four sons: Johanan, and Eliakim (born c. 634 BCE) by Zebudah the daughter of Pedaiah of Rumah; and Mattanyahu (c. 618 BCE) and Shallum (633/632 BCE), both by Hamutal, the daughter of Jeremiah of Libnah.[6] Eliakim had his name changed by Pharaoh Necho of Egypt to Jehoiakim (2 Kings 23:34).

Shallum succeeded Josiah as king of Judah, under the name Jehoahaz.[7] Shallum was succeeded by Eliakim, under the name Jehoiakim,[8] who was succeeded by his own son Jeconiah;[9] then, Jeconiah was succeeded to the throne by Mattanyahu, under the name Zedekiah.[10] Zedekiah was the last king of Judah before the kingdom was conquered by Babylon and the people exiled.

Religious changes

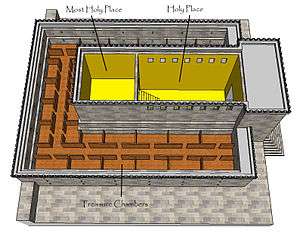

According to the Hebrew Bible, in the eighteenth year of his rule, Josiah ordered the High Priest Hilkiah to use the tax money which had been collected over the years to renovate the temple. It was during this time that Hilkiah discovered the Book of the Law. While Hilkiah was clearing the treasure room of the Temple he discovered a scroll described as "the book of the Law"[5] or as "the book of the law of Yahweh by the hand of Moses". The phrase "the book of the Torah" (ספר התורה, sefer ha-torah) in 2 Kings 22:8 is identical to the phrase used in Joshua 1:8 and 8:34 to describe the sacred writings that Joshua had received from Moses. The book is not identified in the text as the Torah and many scholars believe this was either a copy of the Book of Deuteronomy or a text that became a part of Deuteronomy.[11]

However it has been noted that the story of the repairs to the Temple is based on those ordered by Joash an earlier Judean king (ruled ca. 837 – 800 BCE) in 2 Kings 12.[12]

Hilkiah brought this scroll to Josiah's attention. Josiah consulted the prophetess Huldah, who assured him that the evil foretold in the document for nonobservance of its instructions, would come, but not in his day; "because," she said, "thine heart was tender and thou didst humble thyself before the Lord."[5] An assembly of the elders of Judah and Jerusalem and of all the people was called, and Josiah then encouraged the exclusive worship of Yahweh, forbidding all other forms of worship. The instruments and emblems of the worship of Baal and "the host of heaven,"were removed from the Jerusalem Temple. Local sanctuaries, or High Places, were destroyed, from Beer-sheba in the south to Beth-el and the cities of Samaria in the north.[5] Josiah had pagan priests executed and even had the bones of the dead priests of Bethel exhumed from their graves and burned on their altars. Josiah also reinstituted the Passover celebrations.

According to 1 Kings 13:1–3 an unnamed "man of God" (sometimes identified as Iddo) had prophesied to King Jeroboam of the northern Kingdom of Israel (Samaria), approximately three hundred years earlier, that "a son named Josiah will be born to the house of David" and that he would destroy the altar at Bethel. And the only exception to this destruction was for the grave of an unnamed prophet he found in Bethel (2 Kings 23:15–19), who had foretold that these religious sites Jeroboam erected would one day be destroyed (see 1 Kings 13). Josiah ordered the double grave of the "man of God" and of the Bethel prophet to be let alone as these prophecies had come true.

Josiah's changes are described in two accounts in the Bible, 2 Kings 22-23, and 2 Chronicles 34-35. They began with the ending of ancient Israelite religious practices, and the astral cults that had become popular in the 8th Century, and led to centralisation of worship in Jerusalem, and the destruction of the temple at Bethel.[13]

According to the later account in 2 Chronicles, Josiah destroyed altars and images of pagan deities in cities of the tribes of Manasseh, Ephraim, "and Simeon, as far as Naphtali" (2 Chronicles 34:6–7), which were outside of his kingdom, Judah, and returned the Ark of the Covenant to the Temple.[14]

Foreign relations

When Josiah became king of Judah in about 641/640 BCE, the international situation was in flux. The Assyrian Empire was beginning to disintegrate, the Neo-Babylonian Empire had not yet risen to replace it, and Egypt to the west was still recovering from Assyrian rule. In this power vacuum, Jerusalem was able to govern itself for the time being without foreign intervention.

In the spring of 609 BCE, Pharaoh Necho II led a sizable army up to the Euphrates River to aid the Assyrians against the Babylonians.[15] Taking the coast route Via Maris into Syria at the head of a large army, consisting mainly of mercenaries, and supported by his Mediterranean fleet along the shore, Necho passed the low tracts of Philistia and Sharon. However, the passage over the ridge of hills which shuts in on the south of the great Jezreel Valley was blocked by the Judean army led by Josiah, who may have considered that the Assyrians and Egyptians were weakened by the death of the pharaoh Psamtik I only a year earlier (610 BCE), who had been appointed and confirmed by Assyrian kings Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal.[15] Josiah attempted to block the advance at Megiddo, where a fierce battle was fought and Josiah was killed.[11] Necho then joined forces with the Assyrian Ashur-uballit II and together they crossed the Euphrates and lay siege to Harran. The combined forces failed to capture the city, and Necho retreated to northern Syria.

Death

There are two accounts of Josiah's death in the Bible. The Books of Kings merely state that Necho II met Josiah at Megiddo and killed him (2 Kings 23:29). The Book of Chronicles (2 Chronicles 35:20–27) gives a lengthier account and states that Josiah was fatally wounded by Egyptian archers and was brought back to Jerusalem to die. His death was a result of "not listen[ing] to what Necho had said at God's command..." when Necho stated: "What have I to do with you, king of Judah? I am not coming against you today, but against the house with which I am at war; and God has commanded me to hurry. Cease opposing God, who is with me, so that he will not destroy you." (NRSV)

Josiah did not heed this warning and by both accounts his death was caused by meeting Necho at Megiddo. According to 2 Chronicles 35:25, Jeremiah wrote a lament for Josiah's death.[16]

The account in Chronicles is considered unreliable by some scholars,[17] as it is based on the description of the death of Ahab in 1 Kings, and it meets the Chronicler's religious agenda to attribute the death of a righteous king to some form of sin.[18]

Succession

After the setback in Harran, Necho left a sizable force behind, and returned to Egypt. On his return march, Necho found that Jehoahaz had been selected to succeed his father, Josiah. (2 Kings 23:31) Necho deposed Jehoahaz, who had been king for only three months, and replaced him with his older brother, Jehoiakim. Necho imposed on Judah a levy of a hundred talents of silver (about 3 3⁄4 tons or about 3.4 metric tons) and a talent of gold (about 75 pounds or about 34 kilograms). Necho then took Jehoahaz back to Egypt as his prisoner. The defeat of Josiah at Megiddo essentially represents the end of the rule of the Davidic line, since not only were Josiah's successors short-lived, but also Judah's relative independence had crumbled in the face of a resurgent Egypt bent on regaining its traditional control of the region, and the imminent rise of the Babylonian empire which also sought control.

Necho had left Egypt in 609 BCE for two reasons: one was to relieve the Babylonian siege of Harran, and the other was to help the king of Assyria, who was defeated by the Babylonians at Carchemish. Josiah's actions may have provided aid to the Babylonians by engaging the Egyptian army.[19]

Book of the Law

The Hebrew Bible states that the priest Hilkiah found a "Book of the Law" in the temple during the early stages of Josiah's temple renovation. For much of the 19th and 20th centuries it was agreed among scholars that this was an early version of the Book of Deuteronomy, but recent biblical scholarship sees it as largely legendary narrative about one of the earliest stages of creation of Deuteronomistic work.[20] According to the Bible Hilkiah gave the scroll to his secretary Shaphan who took it to king Josiah.

Historical-critical biblical scholarship generally accepts that this scroll—an early predecessor of the Torah—was written by the priests driven by ideological interest to centralize power under Josiah in the Temple in Jerusalem, and that the core narrative from Joshua to 2 Kings up to Josiah's reign comprises a "Deuteronomistic History" (DtrH) written during Josiah's reign.[21] On the other hand, recent European theologians posit that most of the Torah and Deuteronomistic History was composed and its form finalized during the Persian period, several centuries later.[22]

According to George E. Mendenhall, King Josiah then changed his form of leadership entirely, entering into a new form of covenant with the Lord. Because of what was known as the "book of the law" he wiped out all of the pagan cults that had formed within his land. He, along with his people, then entered into this new covenant with the Lord to keep the commandments of the Lord. According to Mendenhall, in this covenant the Lord was merely a witness to the covenant instead of an actual participant. This defines the covenant as a vassal treaty - a treaty in which the suzerain owes something to its vassals. Because this covenant had just been discovered, it had to be formed into coalition with the covenant that King Josiah's people were already serving under, the Abrahamic covenant.[23]

Sources

The only textual sources of information for Josiah's reign are from the Bible,[4] notably 2 Kings 22–23 and 2 Chronicles 34–35. No archaeological evidence for Josiah as a person exists. Seals and seal impressions from the period stated in the Bible to be that of Josiah's reign show a transition from those of an earlier period which bear images of stars and the moon, to seals that carry only names, a possible indication of Josiah's enforcement of monotheism.[24] No other archaeological evidence for the religious changes attributed to Josiah in the Bible has been discovered.[24]

The date of Josiah's death can fairly well be established. The Babylonian Chronicle dates the battle at Harran between the Assyrians and their Egyptian allies against the Babylonians from Tammuz (July–August) to Elul (August–September) 609 BCE. On that basis, Josiah was killed in the month of Tammuz (July–August) 609 BCE, when the Egyptians were on their way to Harran.[25]

Rabbinic literature

According to Rabbinic interpretation, Huldah said to the messengers of King Josiah, "Tell the man that sent you to me," etc. (2 Kings 22:15), indicating by her unceremonious language that for her Josiah was like any other man. The king addressed her, and not Jeremiah, because he thought that women are more easily stirred to pity than men, and that therefore the prophetess would be more likely than Jeremiah to intercede with God in his behalf (Meg. 14a, b; comp. Seder 'Olam R. xxi.). Huldah was a relative of Jeremiah, both being descendants of Rahab by her marriage with Joshua (Sifre, Num. 78; Meg. 14a, b). While Jeremiah admonished and preached repentance to the men, she did the same to the women (Pesiḳ. R. 26 [ed. Friedmann, p. 129]). Huldah was not only a prophetess, but taught publicly in the school (Targ. to 2 Kings 22:14), according to some teaching especially the oral doctrine. It is doubtful whether "the Gate of Huldah" in the Second Temple (Mid. i. 3) has any connection with the prophetess Huldah; it may have meant "Cat's Gate"; some scholars, however, associate the gate with Huldah's schoolhouse (Rashi to Kings l.c.).E. C. L. G.

The prophetic activity of Jeremiah began in the reign of Josiah; he was a contemporary of his relative the prophetess Hulda and of his teacher Zephaniah (comp. Maimonides in the introduction to "Yad"; in Lam. R. i. 18 Isaiah is mentioned as Jeremiah's teacher). These three prophets divided their activity in such wise that Hulda spoke to the women and Jeremiah to the men in the street, while Zephaniah preached in the synagogue (Pesiḳ. R. l.c.). When Josiah restored the true worship, Jeremiah went to the exiled ten tribes, whom he brought to Israel under the rule of the pious king ('Ar. 33a). Although Josiah went to war with Egypt against the prophet's advice, yet the latter knew that the pious king did so only in error (Lam. R. l.c.); and in his dirges he bitterly laments the king's death, the fourth chapter of the Lamentations beginning with a dirge on Josiah (Lam. R. iv. 1; Targ. II Chron. xxxv. 25).

See also

References

- ↑ Josiah definition - Bible Dictionary - Dictionary.com. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ↑ Wells, John C. (1990). Longman pronunciation dictionary. Harlow, England: Longman. p. 386. ISBN 0-582-05383-8. entry "Josiah"

- ↑ Edwin Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, (1st ed.; New York: Macmillan, 1951; 2d ed.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965; 3rd ed.; Grand Rapids: Zondervan/Kregel, 1983). ISBN 0-8254-3825-X, 9780825438257, 217.

- 1 2 Alpert, Bernard; Alpert, Fran (2012). Archaeology and the Biblical Record. Hamilton Books. p. 74. ISBN 978-0761858355.

- 1 2 3 4 "Josiah", Jewish Encyclopedia

- ↑ 1 Chronicles 3:15, 2 Kings 23:36, 24:18, 23:31

- ↑ 1 Chronicles 3:15, Jeremiah 22:11

- ↑ 2 Chronicles 36:4

- ↑ 2 Chronicles 36:8

- ↑ 2 Kings 24:17

- 1 2 Sweeney, Marvin A. King Josiah of Judah, Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-19-513324-0]

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Judaica | second edition | vol 11 | pg 459

- ↑ Encyclopedia Judaica | second edition | vol 11 | pg 459

- ↑ 2 Chronicles 35:1–4

- 1 2 Coogan, Michael David. The Oxford History of the Biblical World, Oxford University Press, 2001 ISBN 9780195139372

- ↑ Hill, Andrew E., "1 and 2 Chronicles", The NIV Application Commentary, Zondervan, 2010 ISBN 9780310865612

- ↑ Talshir, Zipora, “The Three Deaths of Josiah and the Strata of Biblical Historiography (2 Kings XXIII 29-30; 2 Chronicles XXXV 20-5; 1 Esdras I 23-31), Vetus Testamentum XLVI, 2, 1996

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Judaica, second edition, vol. 11, pg 458-459

- ↑ Gordon D. Fee; Robert L. Jr. Hubbard (4 October 2011). The Eerdmans Companion to the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-8028-3823-0.

- ↑ "The Book of Josiah's Reform", Bible.org. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ↑ Friedman 1987, Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of its Sacred Texts, Touchstone, New York, 2002

- ↑ Konrad Schmid, "The Persian Imperial Authorization as a Historical Problem and as a Biblical Construct," in G.N. Knoppers and B.M. Levison (eds.): The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding its Promulgation and Acceptance, Eisenbrauns 2007

- ↑ Mendenhall, George (September 1954). "Covenant Forms in Israelite Tradition". The Biblical Archaeologist. 17 (3): 73–76.

- 1 2 Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2001). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-86912-4.

- ↑ Thiele, Mysterious Numbers 182, 184–185.

Further reading

- The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts for the possible role of Josiah in creation of the Bible.

- Hertz, J. H. (1936). The Pentateuch and Haftoras. Deuteronomy. Oxford University Press, London.

- Friedman, R. (1987). Who Wrote the Bible? New York: Summit Books.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to King Josiah. |

| Josiah | ||

| Preceded by Amon |

King of Judah 641–610 BCE Died at Tammuz in July–August 609 BCE |

Succeeded by Jehoahaz |