Parliament of Jordan

| Parliament of Jordan مجلس الأمة Majlis Al-Umma | |

|---|---|

| 18th Parliament | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses |

Senate House of Representatives |

Term limits | 4 years |

| History | |

| Founded | January 1, 1952 |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

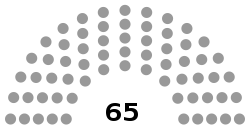

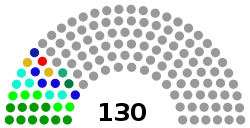

| Seats |

195 members: 65 senators 130 representatives |

| |

Senate political groups |

|

| |

House of Representatives political groups |

|

| Elections | |

Senate voting system | Appointed by the King |

House of Representatives voting system | Open list proportional representation (15 seats reserved for women, nine for Christians, and three for Chechens and Circassians) |

House of Representatives last election | 20 September 2016 |

House of Representatives next election | 2020 or earlier |

| Meeting place | |

| Al-Abdali, Amman | |

| Website | |

|

www | |

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Jordan |

|

|

|

Related topics |

|

|

The Parliament of Jordan (Arabic: مجلس الأمة Majlis Al-Umma) is the bicameral Jordanian national assembly. Established by the 1952 Constitution, the legislature consists of two houses: the Senate ("Majlis Al-Aayan") and the House of Representatives ("Majlis Al-Nuwaab").

The Senate has 65 members, all of whom are directly appointed by the King, while the House of Representatives has 130 elected members, with nine seats reserved for Christians, three are for Circassian and Chechen minorities, and fifteen for women.[1] The members of both houses serve for four-year terms.[2]

Political history

As a developing constitutional monarchy, Jordan has survived the trials and tribulations of Middle Eastern politics. The Jordanian public has experienced limited democracy since gaining independence in 1946 however the population has not suffered as others have under dictatorships imposed by some Arab regimes.[3] The 1952 Constitution provided for citizens of Jordan to form and join political parties.[4] Such rights were suspended in 1967 when a state of emergency was declared and martial law and suspension of Parliament, continuing until it was repealed in 1989.

In 1988 King Hussein cut political ties with the West Bank following the Israeli occupation. Subsequently, civil unrest followed with Prime Minister al-Rifa’i alleged to have used heavy-handed tactics against the population which resulted in riots in April 1989. After the riots had subsided the King fired al-Rifa’i and announced elections for later that year. The King’s action to re-convene parliament elections was considered a significant move forward in enabling the Jordanian public to have greater freedoms and democracy, this has been labelled by the think tank Freedom House as, “the Arab World's most promising experiment in political liberalization and reform”.[5]

The resumption of the parliamentary election was reinforced by new laws governing the media and publishing as well as fewer restrictions on freedoms of expression. Following the legalization of political parties in 1992, 1993 saw the first multi-party elections held since 1956.[6] The country is now one of the most politically open in the Middle East permitting opposition parties such as the Islamic Action Front (IAF), the political wing of the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood. The influence of the IAF significantly reduced in 2007 when their parliamentary representation fell from seventeen to six. The IAF boycotted the 2011 and 2013 elections in protest of the one voice electoral system. The Monarch still holds the true levers of power, appointing members of the House of Senate and has the right to replace the prime minister, a step that King Abdullah II of Jordan took in April 2005.[7]

It has been argued that the influence of tribalism in determining Parliament election results in Jordan should not be overlooked; it is stronger than political affiliations. Tribal identity has a strong influence over Jordanian life: “…identities remain the primary driving forces of decision making at the level of the individual, the community, and the state”.[8]

In 2016, the King of Jordan dissolved the parliament, and named Hani Al-Mulki as Prime Minister.[9]

Legislative procedure

Both houses initiate debates and vote on legislation. Proposals are referred by the Prime Minister to the House of Representatives where they are either accepted, amended or rejected. Every proposal is referred to a committee of the lower house for consideration. If it is approved then it is referred to the government to draft in the form of a bill and submit it to the House of Representatives. If approved by this House, it is passed onto the Senate for debate and a vote. If the Senate gives its approval then the King can either grant consent or refuse. In this case the bill is passed back to the House of Deputies where the review and voting process is repeated. If both houses pass the bill by a two-thirds majority it becomes an Act of Parliament overriding the King’s veto. Article 95 of the Constitution empowers both houses to submit legislation to the government in the form of a draft law.[10]

The Constitution does not provide a strong system of checks and balances within which the Jordanian Parliament can assert its role in relationship to the Monarch. During the suspension of Parliament between 2001 and 2003, the scope of King Abdullah II’s power was demonstrated with the passing of 110 temporary laws. Two of such laws dealt with election law and were created to reduce the power of Parliament.[11][12]

Term

Senators have terms of four years and are appointed by the King and can be reappointed. Prospective Senators must be at least forty years old and have held senior positions in either the government or military. Appointed senators have included former prime ministers and members of the House of Representatives. Deputies are elected to serve a four-year term. Deputy candidates must be older than thirty five and cannot be related to the king and must not have any financial interests in governmental contracts.[13]

Political parties in the House of Representatives

Despite the reforms of 1989, multi-party politics has yet to develop in Jordan. The only political party that plays a role in the legislature is the Islamic Action Front (IAF). Political parties can be seen to represent four sections: Islamists, leftists, Arab nationalists and conservative. There are 34 registered political parties in Jordan including the Jordanian Arab Democratic Party, Jordanian Socialist Party, Muslim Centre Party, but these have little impact on the political process. Legislation regarding political parties was passed in March 2007 which made it a requirement that all political parties had to report to the Ministry of the Interior and have a minimum of five hundred founding members from at least five governorates. This was seen by some as a direct threat to a number of the political parties which are small in membership.[14]

Public disillusion with existing political parties has been highlighted in research carried out by the Centre for Strategic Studies at Jordan University. The investigation concluded that in 2007 only 9.7% of respondents felt that the political parties represented their political, economic and social aspirations. Furthermore, 80% of respondents believed that ‘none’ of the political parties were ‘qualified to form a government’.[15]

Permanent committees

Legal, Financial, Administrative and Foreign Affairs. Both houses have the ability to create committees when required.

Current weakness

- Low voter turnout has indicated that there is a problem with public participation in the democratic process, with the following turnouts for previous elections: 2007 54%[16] 2003 58%;[17] 1997 44%; 1993 47%; 1989 41%[18]

- Practical issues have reduced the effect of Parliament with brief parliamentary sessions (November to March) and a lack of resources and support for members of both houses[19]

- There has been a lack of involvement in Jordanian politics of political parties. This was further reduced through the Boycotting of previous elections by the IAF (1997)[20] which represented the only real political party as the vast majority of elected parliamentarians ran as independents based on tribal lines or families close to the king.

Democratization

The Jordanian Parliament and its form of democracy are young in comparison to their western contemporaries. According to Kaaklini et al., “Since 1989, it [Jordanian Parliament] has become a more credible, representative, and influential institution. Still, serious constitutional, political, and internal hurdles continue to prevent it from enjoying the prerogatives and from performing the range of functions that are appropriate for a legislature in a democratic system”.[21] Judged against other states in the Middle East, Jordan has made significant progress towards a democratic system of government.

It has been argued that the Jordanian Parliament is part of a democracy that has not been achieved by other states within the Middle East. However, in comparison to elected democracies as associated with ‘western’ nations, Jordan may not be considered to have occurred as the monarchy continues to dominate national politics, “…1989 elections brought unparalleled political liberalization and somewhat greater democratic input… although the political supremacy of the palace has been rendered less visible by the more active role of parliament, it is clear that a fundamental transfer of power into elected hands has not yet occurred.”.[22]

See also

- List of Presidents of the Senate of Jordan

- List of Speakers of the House of Representatives of Jordan

- Jordanian local elections, 2017

- Jordanian general election, 2016

- Jordanian general election, 2013

- Jordanian general election, 2010

- Politics of Jordan

- List of legislatures by country

References

- ↑ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/jo.html

- ↑ "World Factbook: Jordan", U.S. Central Intelligence Agency

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20061117165033/http://www.uk.oneworld.net/guides/jordan/development

- ↑ http://www.idea.int/publications/dem_jordan/upload/Jordan_country_report_English.pdf

- ↑ Countries at the Crossroads 2006 Country Report – Jordan http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=140&edition=7&ccrpage=31&ccrcountry=118

- ↑ Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs. Profile: Jordan. March 2008.

- ↑ UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Jordan: Year in Brief 2005 – A chronology of democratic developments. 15/01/2006.

- ↑ Khouri 2003 p.147 as quoted in World Bank 2003 ‘Better governance for development in the Middle East and North Africa: enhancing inclusiveness and accountability’ Washington

- ↑ "Jordan's King Abdullah dissolves parliament, names caretaker PM". todayonline.com. Mediacorp Press Ltd. 29 May 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ http://www.kinghussein.gov.jo/government3html

- ↑ p.148 Parker, C. 2004 ‘Transformation without transition: electoral politics, network ties, and the persistence of the shadow state in Jordan’ in Elections in the Middle East: what do they mean’ Cairo Papers in Social Sciences Vol. 25 Numbers ½, Spring Summer 2002 Cairo

- ↑ World Bank 2003 p.44 ‘Better governance for development in the Middle East and North Africa: Enhancing inclusiveness and accountability’ Washington

- ↑ http://www.lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+jo0103)

- ↑ Economist Intelligence Unit 23/07/2007 ‘Political Forces’ http://www.economist.com/countries/Jordan/profile.cfm?folder=Profile-Political%20Forces

- ↑ Dr. Braizat, F. Public Opinion Poll Unit Centre For Strategic Studies Jordan University 12/07 ‘Democracy in Jordan 2007’ www.jcss.org/UploadPolling/258.pdf

- ↑ electionguide.org/details.aspz/3/Jordan/8/Election%20Results/article984

- ↑ http://www.pogar.org/countries/elections.asp?cid=7 United Nations Development Programme Democratic Governance Jordan

- ↑ Ryan, C. 2002 ‘Jordan in transition: From Hussein to Abdullah’ Lynne Rienner Publishers London p.39

- ↑ page167Baaklini, A., Denoeux, G. & Springborg, R. 1999 ‘Legislative Politics in the Arab World: The resurgence of Democratic Institutions’ Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc. London

- ↑ Hamzeh, A. 10//11/2001 ‘IAF resignations rekindle tension with government’ Jordan Times http://www.jordanembassyus.org/08102001002.htm

- ↑ Kaaklini, A. Denouex, G & Springborg, R 1999 page 165 ‘Legislative Politics in the Arab world: the resurgence of democratic institutions’ Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc. London

- ↑ p.79 Brynen, R. ‘The Politics of Monarchical Liberalism: Jordan’ Political Liberalization and democratization in the Arab world’ Volume 2, comparative experiences: Korany, B. Brynen , R . Noble, P. Lynne Rienner London

Coordinates: 31°57′44.4″N 35°54′43.2″E / 31.962333°N 35.912000°E

External links

- Parliament of Jordan

- House of Representatives

- Senate

- Sculptor Annette Yarrow on being commissioned to produce a statue for the Jordanian Parliament building