Joint (building)

A building joint is a junction where building elements meet without applying a static load from one element to another. When one or more of these vertical or horizontal elements that meet are required by the local building code to have a fire-resistance rating, the resulting opening that makes up the joint must be firestopped in order to restore the required compartmentalisation.

Qualification requirements

Such joints are often subject to movement, as a function of the building's design basis. For a sample certification listing indicating fire tested motion, click here. Firestops must be able to demonstrate the ability to withstand operational movement prior to fire testing. Firestops for such building joints can be qualified to UL 2079 -- Tests for Fire Resistance of Building Joint Systems.

Whether or not the building elements forming the joint have a fire-resistance rating, the joint design must still consider the anticipated operational movement of each joint. Timing is also important, as freshly poured concrete shrinks [1] particularly during the first few months of a new building, potentially causing joint size changes.

Perimeter slab edge

Firestopping at the "perimeter slab edge", which is gaps between the floors and the backpan of the curtain wall or precast concrete panels, slow the passage of fire and combustion gases between floors. The firestop at the perimeter slab edge is considered a continuation of the fire-resistance rating of the floor slab. The curtain wall itself, however, is not ordinarily required to have a rating. Fire compartmentalisation is based upon compartments enclosed on all sides to avoid fire and smoke migration beyond each engaged compartment. A non-fire-resistance rated curtain wall prevents the complete compartment (or envelope) from being fire-resistance rated. The provision of firestopping at the joint of the floor slab and curtain wall can still add to the overall fire safety of the building by slowing the advance of the fire in the building interior from floor to floor. The use of fire sprinklers has been shown to mitigate the spread of fire by keeping the fire from growing to a size large enough to cause structural damage and break the exterior glass. If the building is not equipped with sprinklers, the fire can travel up the outside of the curtain wall if the glass on the floor of fire origin is shattered due to radiant heat, causing flames to lick up the outside of the building, resulting in the glass in floors above to break. Falling glass can endanger pedestrians, firefighters and firehoses below. An example of mode of fire spread is the First Interstate Bank Fire in Los Angeles, California.[2] This building is now the Aon Center.

The fire leapfrogged up the tower by shattering the glass. The exterior curtain wall aluminium skeleton holding the glass failed. Exceptionally sound cementitious spray fireproofing also helped to delay and ultimately to avoid the possible collapse of the building,[3] by preventing the steel building structure from reaching the critical temperature at which steel weakens and can no longer hold its intended load.[4] This fire proved the positive, collective effect of both active fire protection (sprinklers) to control fire size in its incipient stages,[5] and passive fire protection (fireproofing) if the fire sprinklers are not effective.[6]

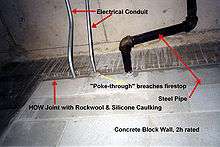

Head-of-Wall (HOW)

Where fire-resistance rated wall assemblies, be they masonry or drywall, meet the underside of the floor slab above, a movement joint results, which can be subject to compression, as the freshly placed concrete cures and shrinks all over a new building. This joint must be firestopped in a flexible manner. For concrete block walls that are not load-bearing, the contractor is often instructed to stop the wall about 25mm short of the slab above. The drywaller has to fasten a track to the underside of the slab above, which holds the metal studs. The drywall is then either stopped short allowing for a flexible buffer to be inserted or caulked in place, or one may use purpose-made tracks that hold the studs but permit up and down movement without damage to the system.

See also

- Concrete

- Penetration (firestop)

- Sealant

- Firestop

- Curtain wall

- Passive fire protection

- Active fire protection

- Mineral wool

- Packing (firestopping)

- Fire sprinkler

- Articulation

References

- ↑ "Cement Association of Canada - Drying Shrinkage". Cement Association of Canada. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- ↑ http://www.lafire.com/famous_fires/880504_1stInterstateFire/exsummary/LAFD-ExecutiveSummary.htm Los Angeles Fire Department Historical Archive

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-07-13. Retrieved 2010-07-13. p. 21

- ↑ http://www.modernsteel.com/Uploads/Issues/March_2004/30727_clifton-feeney.pdf

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-07-13. Retrieved 2010-07-13. p. 18

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-07-13. Retrieved 2010-07-13. p. 20

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Building Joints. |

- UL2079 Scope: Tests for Fire Resistance of Building Joint Systems

- UL treatise on building joints

- UL HW-S-0055: A common condition