Claisen rearrangement

| Claisen rearrangement | |

|---|---|

| Named after | Rainer Ludwig Claisen |

| Reaction type | Rearrangement reaction |

| Identifiers | |

| Organic Chemistry Portal | claisen-rearrangement |

| RSC ontology ID | RXNO:0000148 |

The Claisen rearrangement (not to be confused with the Claisen condensation) is a powerful carbon–carbon bond-forming chemical reaction discovered by Rainer Ludwig Claisen. The heating of an allyl vinyl ether will initiate a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement to give a γ,δ-unsaturated carbonyl.

Discovered in 1912, the Claisen rearrangement is the first recorded example of a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement.[1][2][3] Many reviews have been written.[4][5][6][7]

Mechanism

The Claisen rearrangement is an exothermic, concerted (bond cleavage and recombination) pericyclic reaction. Woodward–Hoffmann rules show a suprafacial, stereospecific reaction pathway. The kinetics are of the first order and the whole transformation proceeds through a highly ordered cyclic transition state and is intramolecular. Crossover experiments eliminate the possibility of the rearrangement occurring via an intermolecular reaction mechanism and are consistent with an intramolecular process.[8][9]

There are substantial solvent effects observed in the Claisen rearrangement, where polar solvents tend to accelerate the reaction to a greater extent. Hydrogen-bonding solvents gave the highest rate constants. For example, ethanol/water solvent mixtures give rate constants 10-fold higher than sulfolane.[10][11] Trivalent organoaluminium reagents, such as trimethylaluminium, have been shown to accelerate this reaction.[12][13]

Variations

Aromatic Claisen rearrangement

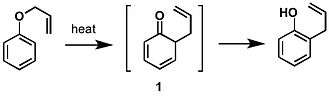

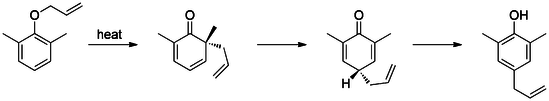

The first reported Claisen rearrangement is the [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of an allyl phenyl ether to intermediate 1, which quickly tautomerizes to an ortho-substituted phenol.

Meta-substitution affects the regioselectivity of this rearrangement.[14][15] For example, electron withdrawing groups (e.g. bromide) at the meta-position direct the rearrangement to the ortho-position (71% ortho-product), while electron donating groups (e.g. methoxy), direct rearrangement to the para-position (69% para-product). Additionally, presence of ortho-substituents exclusively leads to para-substituted rearrangement products (tandem Claisen and Cope rearrangement).[16]

If an aldehyde or carboxylic acid occupies the ortho or para positions, the allyl side-chain displaces the group, releasing it as carbon monoxide or carbon dioxide, respectively.[17][18]

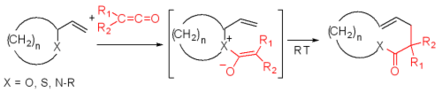

Bellus–Claisen rearrangement

The Bellus–Claisen rearrangement is the reaction of allylic ethers, amines, and thioethers with ketenes to give γ,δ-unsaturated esters, amides, and thioesters.[19][20][21] This transformation was serendipitously observed by Bellus in 1979 through their synthesis of a key intermediate of an insecticide, pyrethroid. Halogen substituted ketenes (R1, R2) are often used in this reaction for their high electrophilicity. Numerous reductive methods for the removal of the resulting α-haloesters, amides and thioesters have been developed.[22][23] The Bellus-Claisen offers synthetic chemists a unique opportunity for ring expansion strategies.

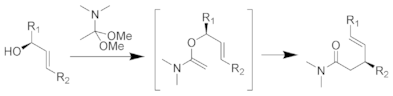

Eschenmoser–Claisen rearrangement

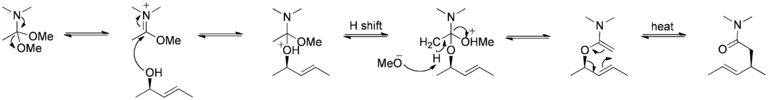

The Eschenmoser–Claisen rearrangement proceeds by heating allylic alcohols in the presence of N,N-dimethylacetamide dimethyl acetal to form γ,δ-unsaturated amide. This was developed by Albert Eschenmoser in 1964.[24][25] Eschenmoser-Claisen rearrangement was used as a key step in the total synthesis of morphine.[26]

Mechanism:[16]

Ireland–Claisen rearrangement

The Ireland–Claisen rearrangement is the reaction of an allylic carboxylate with a strong base (such as lithium diisopropylamide) to give a γ,δ-unsaturated carboxylic acid.[27][28][29] The rearrangement proceeds via silylketene acetal, which is formed by trapping the lithium enolate with chlorotrimethylsilane. Like the Bellus-Claisen (above), Ireland-Claisen rearrangement can take place at room temperature and above. The E- and Z-configured silylketene acetals lead to anti and syn rearranged products, respectively.[30] There are numerous examples of enantioselective Ireland-Claisen rearrangements found in literature to include chiral boron reagents and the use of chiral auxiliaries.[31][32]

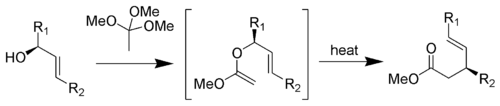

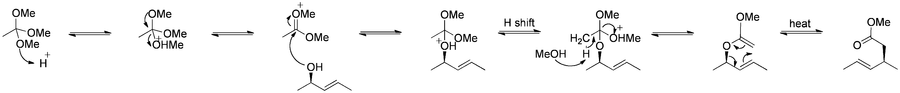

Johnson–Claisen rearrangement

The Johnson–Claisen rearrangement is the reaction of an allylic alcohol with an orthoester to yield a γ,δ-unsaturated ester.[33] Weak acids, such as propionic acid, have been used to catalyze this reaction. This rearrangement often requires high temperatures (100 to 200 °C) and can take anywhere from 10 to 120 hours to complete.[34] However, microwave assisted heating in the presence of KSF-clay or propionic acid have demonstrated dramatic increases in reaction rate and yields.[35][36]

Mechanism:[16]

Photo-Claisen rearrangement

The photo-Claisen rearrangement is closely related to the photo-Fries rearrangement, that proceeds through a similar radical mechanism. Aryl ethers undergo the photo-Claisen rearrangement, while the photo-Fries rearrangement utilizes aryl esters.[37]

Hetero-Claisens

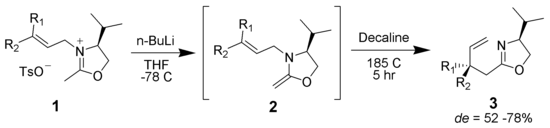

Aza–Claisen

An iminium can serve as one of the pi-bonded moieties in the rearrangement.[38]

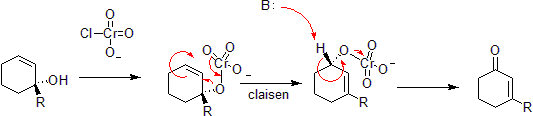

Chromium oxidation

Chromium can oxidize allylic alcohols to alpha-beta unsaturated ketones on the opposite side of the unsaturated bond from the alcohol. This is via a concerted hetero-Claisen reaction, although there are mechanistic differences since the chromium atom has access to d- shell orbitals which allow the reaction under a less constrained set of geometries.[39][40]

Chen–Mapp reaction

The Chen–Mapp reaction also known as the [3,3]-Phosphorimidate Rearrangement or Staudinger–Claisen Reaction installs a phosphite in the place of an alcohol and takes advantage of the Staudinger reduction to convert this to an imine. The subsequent Claisen is driven by the fact that a P=O double bond is more energetically favorable than a P=N double bond.[41]

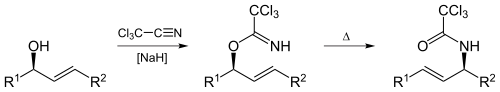

Overman rearrangement

The Overman rearrangement (named after Larry Overman) is a Claisen rearrangement of allylic trichloroacetimidates to allylic trichloroacetamides.[42][43][44]

Overman rearrangement is applicable to synthesis of vicinol diamino comp from 1,2 vicinal allylic diol.

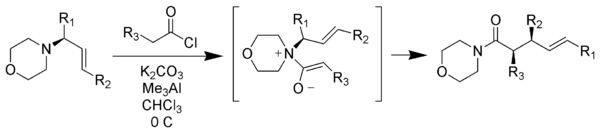

Zwitterionic Claisen rearrangement

Unlike typical Claisen rearrangements which require heating, zwitterionic Claisen rearrangements take place at or below room temperature. The acyl ammonium ions are highly selective for Z-enolates under mild conditions.[45][46]

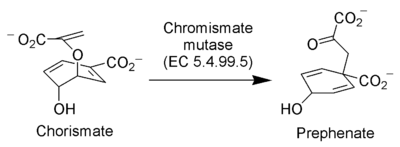

Claisen rearrangement in nature

The enzyme Chorismate mutase (EC 5.4.99.5) catalyzes the Claisen rearrangement of chorismate ion to prephenate ion, a key intermediate in the shikimic acid pathway (the biosynthetic pathway towards the synthesis of phenylalanine and tyrosine).[47]

See also

References

- ↑ Claisen, L. (1912). "Über Umlagerung von Phenol-allyläthern in C-Allyl-phenole". Chemische Berichte. 45 (3): 3157–3166. doi:10.1002/cber.19120450348.

- ↑ Claisen, L.; Tietze, E. (1925). "Über den Mechanismus der Umlagerung der Phenol-allyläther". Chemische Berichte. 58 (2): 275. doi:10.1002/cber.19250580207.

- ↑ Claisen, L.; Tietze, E. (1926). "Über den Mechanismus der Umlagerung der Phenol-allyläther. (2. Mitteilung)". Chemische Berichte. 59 (9): 2344. doi:10.1002/cber.19260590927.

- ↑ Hiersemann, M.; Nubbemeyer, U. (2007) The Claisen Rearrangement. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-30825-3

- ↑ Rhoads, S. J.; Raulins, N. R. (1975). "The Claisen and Cope Rearrangements". Org. React. 22: 1–252. ISBN 0471264180. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or022.01.

- ↑ Ziegler, F. E. (1988). "The thermal, aliphatic Claisen rearrangement". Chem. Rev. 88 (8): 1423–1452. doi:10.1021/cr00090a001.

- ↑ Wipf, P. (1991). "Claisen Rearrangements". Comp. Org. Syn. 5: 827–873. ISBN 978-0-08-052349-1. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-052349-1.00140-2.

- ↑ Hurd, C. D.; Schmerling, L. (1937). "Observations on the Rearrangement of Allyl Aryl Ethers". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 59: 107. doi:10.1021/ja01280a024.

- ↑ Francis A. Carey; Richard J. Sundberg (2007). Advanced Organic Chemistry: Part A: Structure and Mechanisms. Springer. pp. 934–935. ISBN 978-0-387-44897-8.

- ↑ Claisen, L. (1912). "Über Umlagerung von Phenol-allyläthern in C-Allyl-phenole". Chemische Berichte. 45 (3): 3157–3166. doi:10.1002/cber.19120450348.

- ↑ Claisen, L.; Tietze, E. (1925). "Über den Mechanismus der Umlagerung der Phenol-allyläther". Chemische Berichte. 58 (2): 275. doi:10.1002/cber.19250580207.

- ↑ Goering, H. L.; Jacobson, R. R. (1958). "A Kinetic Study of the ortho-Claisen Rearrangement1". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80 (13): 3277. doi:10.1021/ja01546a024.

- ↑ White, W. N.; Wolfarth, E. F. (1970). "The o-Claisen rearrangement. VIII. Solvent effects". J. Org. Chem. 35 (7): 2196. doi:10.1021/jo00832a019.

- ↑ White, William; and Slater, Carl, William N.; Slater, Carl D. (1961). "The ortho-Claisen Rearrangement. V. The Products of Rearrangement of Allyl m-X-Phenyl Ethers". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 26 (10): 3631–3638. doi:10.1021/jo01068a004.

- ↑ Gozzo, Fábio; Fernandes, Sergio; Rodrigues, Denise; Eberlin, Marcos; and Marsaioli, Anita, Fábio Cesar; Fernandes, Sergio Antonio; Rodrigues, Denise Cristina; Eberlin, Marcos Nogueira; Marsaioli, Anita Jocelyne (2003). "Regioselectivity in Aromatic Claisen Rearrangements". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 68 (14): 5493–5499. PMID 12839439. doi:10.1021/jo026385g.

- 1 2 3 László Kürti; Barbara Czakó (2005). Strategic Applications Of Named Reactions In Organic Synthesis: Background And Detailed Mechanics: 250 Named Reactions. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-429785-2. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ↑ Adams, Rodger (1944). Organic Reactions, Volume II. Newyork: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Claisen, L.; Eisleb, O. (1913). "Über die Umlagerung von Phenolallyläthern in die isomeren Allylphenole". Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 401 (1): 90. doi:10.1002/jlac.19134010103.

- ↑ Malherbe, R.; Bellus, D. (1978). "A New Type of Claisen Rearrangement Involving 1,3-Dipolar Intermediates. Preliminary communication". Helv. Chim. Acta. 61 (8): 3096–3099. doi:10.1002/hlca.19780610836.

- ↑ Malherbe, R.; Rist, G.; Bellus, D. (1983). "Reactions of haloketenes with allyl ethers and thioethers: A new type of Claisen rearrangement". J. Org. Chem. 48 (6): 860–869. doi:10.1021/jo00154a023.

- ↑ Gonda, J. (2004). "The Belluš–Claisen Rearrangement". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43 (27): 3516–3524. doi:10.1002/anie.200301718.

- ↑ Edstrom, E (1991). "An unexpected reversal in the stereochemistry of transannular cyclizations. A stereoselective synthesis of (±)-epilupinine.". Tetrahedron Letters. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)93536-6.

- ↑ Bellus (1983). "Reactions of haloketenes with allyl ethers and thioethers: a new type of Claisen rearrangement". JOC. doi:10.1021/jo00154a023.

- ↑ Wick, A. E.; Felix, D.; Steen, K.; Eschenmoser, A. (1964). "CLAISEN'sche Umlagerungen bei Allyl- und Benzylalkoholen mit Hilfe von Acetalen des N, N-Dimethylacetamids. Vorläufige Mitteilung". Helv. Chim. Acta. 47 (8): 2425–2429. doi:10.1002/hlca.19640470835.

- ↑ Wick, A. E.; Felix, D.; Gschwend-Steen, K.; Eschenmoser, A. (1969). "CLAISEN'sche Umlagerungen bei Allyl- und Benzylalkoholen mit 1-Dimethylamino-1-methoxy-äthen". Helv. Chim. Acta. 52 (4): 1030–1042. doi:10.1002/hlca.19690520418.

- ↑ Guillou, C (2008). "Diastereoselective Total Synthesis of (±)-Codeine". Chem. Eur. J. doi:10.1002/chem.200800744.

- ↑ Ireland, R. E.; Mueller, R. H. (1972). "Claisen rearrangement of allyl esters". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 94 (16): 5897. doi:10.1021/ja00771a062.

- ↑ Ireland, R. E.; Willard, A. K. (1975). "The stereoselective generation of ester enolates". Tetrahedron Lett. 16 (46): 3975–3978. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)91213-9.

- ↑ Ireland, R. E.; Mueller, R. H.; Willard, A. K. (1976). "The ester enolate Claisen rearrangement. Stereochemical control through stereoselective enolate formation". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 98 (10): 2868. doi:10.1021/ja00426a033.

- ↑ Ireland, R. E. (1991). "Stereochemical control in the ester enolate Claisen rearrangement.". JOC. doi:10.1021/jo00002a030.

- ↑ Enders, E (1996). "Asymmetric [3.3]-sigmatropic rearrangements in organic synthesis". Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. doi:10.1016/0957-4166(96)00220-0.

- ↑ Corey, E (1991). "Highly enantioselective and diastereoselective Ireland-Claisen rearrangement of achiral allylic esters". JACS. doi:10.1021/ja00010a074.

- ↑ Johnson, William Summer; Werthemann, Lucius; Bartlett, William R.; Brocksom, Timothy J.; Li, Tsung-Tee; Faulkner, D. John; Petersen, Michael R. (1970-02-01). "Simple stereoselective version of the Claisen rearrangement leading to trans-trisubstituted olefinic bonds. Synthesis of squalene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 92 (3): 741–743. ISSN 0002-7863. doi:10.1021/ja00706a074.

- ↑ Fernandes, R. A. (2013). "The Orthoester Johnson–Claisen Rearrangement in the Synthesis of Bioactive Molecules, Natural Products, and Synthetic Intermediates – Recent Advances". Eur JOC. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201301033.

- ↑ Huber, R. S. (1992). "Acceleration of the orthoester Claisen rearrangement by clay catalyzed microwave thermolysis: expeditious route to bicyclic lactones". JOC. doi:10.1021/jo00047a041.

- ↑ Srikrishna, A (1995). "Application of microwave heating technique for rapid synthesis of γ,δ-unsaturated esters". Tetrahedron. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(94)01058-8.

- ↑ IUPAC. Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book"). Compiled by A. D. McNaught and A. Wilkinson. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford (1997). XML on-line corrected version: http://goldbook.iupac.org (2006–) created by M. Nic, J. Jirat, B. Kosata; updates compiled by A. Jenkins. ISBN 0-9678550-9-8. doi:10.1351/goldbook

- ↑ Kurth, M. J.; Decker, O. H. W. (1985). "Enantioselective preparation of 3-substituted 4-pentenoic acids via the Claisen rearrangement". J. Org. Chem. 50 (26): 5769–5775. doi:10.1021/jo00350a067.

- ↑ Dauben, W. G.; Michno, D. M. (1977). "Direct oxidation of tertiary allylic alcohols. A simple and effective method for alkylative carbonyl transposition". J. Org. Chem. 42 (4): 682. doi:10.1021/jo00424a023.

- ↑ "(R)-(+)-3,4-DIMETHYLCYCLOHEX-2-EN-1-ONE [(R)-(+)-3,4-Dimethyl-2-cyclohexen-1-one]". www.orgsyn.org. Retrieved 2016-10-09.

- ↑ Chen, B.; Mapp, A. (2005). "Thermal and catalyzed 3,3-phosphorimidate rearrangements". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (18): 6712–6718. PMID 15869293. doi:10.1021/ja050759g.

- ↑ Overman, L. E. (1974). "Thermal and mercuric ion catalyzed [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of allylic trichloroacetimidates. 1,3 Transposition of alcohol and amine functions". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 96 (2): 597–599. doi:10.1021/ja00809a054.

- ↑ Overman, L. E. (1976). "A general method for the synthesis of amines by the rearrangement of allylic trichloroacetimidates. 1,3 Transposition of alcohol and amine functions". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 98 (10): 2901–2910. doi:10.1021/ja00426a038.

- ↑ Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 6, p.507; Vol. 58, p.4 (Article)

- ↑ Yu, C.-M.; Choi, H.-S.; Lee, J.; Jung, W.-H.; Kim, H.-J. (1996). "Self-regulated molecular rearrangement: Diastereoselective zwitterionic aza-Claisen protocol". J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 (2): 115–116. doi:10.1039/p19960000115.

- ↑ Nubbemeyer, U. (1995). "1,2-Asymmetric Induction in the Zwitterionic Claisen Rearrangement of Allylamines". J. Org. Chem. 60 (12): 3773–3780. doi:10.1021/jo00117a032.

- ↑ Ganem, B. (1996). "The Mechanism of the Claisen Rearrangement: Déjà Vu All over Again". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 35 (9): 936–945. doi:10.1002/anie.199609361.