Calvin Coolidge

| Calvin Coolidge | |

|---|---|

Coolidge, photographed in 1919 when he was governor of Massachusetts | |

| 30th President of the United States | |

|

In office August 2, 1923 – March 4, 1929 | |

| Vice President |

None (1923–1925) Charles G. Dawes (1925–1929) |

| Preceded by | Warren G. Harding |

| Succeeded by | Herbert Hoover |

| 29th Vice President of the United States | |

|

In office March 4, 1921 – August 2, 1923 | |

| President | Warren G. Harding |

| Preceded by | Thomas R. Marshall |

| Succeeded by | Charles G. Dawes |

| 48th Governor of Massachusetts | |

|

In office January 2, 1919 – January 6, 1921 | |

| Lieutenant | Channing H. Cox |

| Preceded by | Samuel W. McCall |

| Succeeded by | Channing H. Cox |

| 46th Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts | |

|

In office January 6, 1916 – January 2, 1919 | |

| Governor | Samuel W. McCall |

| Preceded by | Grafton D. Cushing |

| Succeeded by | Channing H. Cox |

| President of the Massachusetts Senate | |

|

In office 1914–1915 | |

| Preceded by | Levi H. Greenwood |

| Succeeded by | Henry Gordon Wells |

| Member of the Massachusetts Senate | |

|

In office 1912–1915 | |

| Mayor of Northampton, Massachusetts | |

|

In office 1910–1911 | |

| Preceded by | James W. O'Brien |

| Succeeded by | William Feiker |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives | |

|

In office 1907–1908 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

John Calvin Coolidge Jr. July 4, 1872 Plymouth Notch, Vermont, U.S. |

| Died |

January 5, 1933 (aged 60) Northampton, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Coronary thrombosis |

| Resting place | Plymouth Notch Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Grace Goodhue (m. 1905) |

| Children | 2, including John Coolidge |

| Alma mater | Amherst College |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature |

|

John Calvin Coolidge Jr. (/ˈkuːlɪdʒ/; July 4, 1872 – January 5, 1933) was the 30th President of the United States (1923–29). A Republican lawyer from Vermont, Coolidge worked his way up the ladder of Massachusetts state politics, eventually becoming governor of that state. His response to the Boston Police Strike of 1919 thrust him into the national spotlight and gave him a reputation as a man of decisive action. Soon after, he was elected as the 29th vice president in 1920 and succeeded to the presidency upon the sudden death of Warren G. Harding in 1923. Elected in his own right in 1924, he gained a reputation as a small-government conservative, and also as a man who said very little, although having a rather dry sense of humor.

Coolidge restored public confidence in the White House after the scandals of his predecessor's administration, and left office with considerable popularity.[1] As a Coolidge biographer wrote, "He embodied the spirit and hopes of the middle class, could interpret their longings and express their opinions. That he did represent the genius of the average is the most convincing proof of his strength."[2] Coolidge's retirement was relatively short, as he died at the age of 60 in January 1933, less than two months before his immediate successor, Herbert Hoover, left office.

Although his reputation underwent a renaissance during the Reagan administration, modern assessments of Coolidge's presidency are divided. He is adulated among advocates of smaller government and laissez-faire; supporters of an active central government generally view him less favorably, while both sides praise his stalwart support of racial equality.[3]

Birth and family history

John Calvin Coolidge Jr. was born in Plymouth Notch, Windsor County, Vermont, on July 4, 1872, the only U.S. president to be born on Independence Day. He was the elder of the two children of John Calvin Coolidge Sr. (1845–1926) and Victoria Josephine Moor (1846–85). Coolidge Senior engaged in many occupations, but developed a statewide reputation as a prosperous farmer, storekeeper and public servant. He held various local offices, including justice of the peace and tax collector and served in the Vermont House of Representatives as well as the Vermont Senate.[4] Coolidge's mother was the daughter of a Plymouth Notch farmer. She was chronically ill and died, perhaps from tuberculosis, when Coolidge was twelve years old. His younger sister, Abigail Grace Coolidge (1875–1890), died at the age of fifteen, probably of appendicitis, when Coolidge was eighteen. Coolidge's father remarried in 1891, to a schoolteacher, and lived to the age of eighty.[5]

Coolidge's family had deep roots in New England; his earliest American ancestor, John Coolidge, emigrated from Cottenham, Cambridgeshire, England, around 1630 and settled in Watertown, Massachusetts.[6] Another ancestor, Edmund Rice, arrived at Watertown in 1638. Coolidge's great-great-grandfather, also named John Coolidge, was an American military officer in the Revolutionary War and one of the first selectmen of the town of Plymouth Notch.[7] His grandfather, Calvin Galusha Coolidge, served in the Vermont House of Representatives.[8] Many of Coolidge's ancestors were farmers, and numerous distant cousins were prominent in politics.

Early career and marriage

Education and law practice

Coolidge attended Black River Academy and then St. Johnsbury Academy, before enrolling at Amherst College, where he distinguished himself in the debating class, as a senior joined the fraternity Phi Gamma Delta and graduated cum laude. While there, Coolidge was profoundly influenced by philosophy professor Charles Edward Garman, a Congregational mystic, with a neo-Hegelian philosophy.

Coolidge explained Garman's ethics forty years later,

there is a standard of righteousness that might does not make right, that the end does not justify the means, and that expediency as a working principle is bound to fail. The only hope of perfecting human relationships is in accordance with the law of service under which men are not so solicitous about what they shall get as they are about what they shall give. Yet people are entitled to the rewards of their industry. What they earn is theirs, no matter how small or how great. But the possession of property carries the obligation to use it in a larger service...[9]

At his father's urging after graduation, Coolidge moved to Northampton, Massachusetts to become a lawyer. To avoid the cost of law school, Coolidge followed the common practice of apprenticing with a local law firm, Hammond & Field, and reading law with them. John C. Hammond and Henry P. Field, both Amherst graduates, introduced Coolidge to law practice in the county seat of Hampshire County. In 1897, Coolidge was admitted to the Massachusetts bar, becoming a country lawyer.[10] With his savings and a small inheritance from his grandfather, Coolidge opened his own law office in Northampton in 1898. He practiced commercial law, believing that he served his clients best by staying out of court. As his reputation as a hard-working and diligent attorney grew, local banks and other businesses began to retain his services.[11]

Marriage and family

In 1903, Coolidge met Grace Anna Goodhue, a University of Vermont graduate and teacher at Northampton's Clarke School for the Deaf. They married on October 4, 1905 at 2:30 p.m. in a small ceremony which took place in the parlor of Grace's family's house, following a vain effort at postponement by Grace's mother; she was never enamored with Coolidge, nor he with her.[12] The newlyweds went on a honeymoon trip to Montreal, originally planned for two weeks but cut short by a week at Coolidge's request. After 25 years he wrote of Grace, "for almost a quarter of a century she has borne with my infirmities and I have rejoiced in her graces".[13]

The Coolidges had two sons: John (September 7, 1906 – May 31, 2000) and Calvin Jr. (April 13, 1908 – July 7, 1924). Calvin's death at age 16 from blood poisoning brought on by an infected blister "hurt him terribly," according to son John. John became a railroad executive, helped to start the Coolidge Foundation, and was instrumental in creating the President Calvin Coolidge State Historic Site.[14] Coolidge was frugal, and when it came to securing a home, he insisted upon renting. Henry Field had a pew in Edwards Congregational Church, and Grace was a member, but Coolidge never formally joined the congregation.[15]

Local political office

City offices

The Republican Party was dominant in New England in Coolidge's time, and he followed Hammond's and Field's example by becoming active in local politics.[16] In 1896, Coolidge campaigned for Republican presidential candidate William McKinley, and the next year he was selected to be a member of the Republican City Committee.[17] In 1898, he won election to the City Council of Northampton, placing second in a ward where the top three candidates were elected.[16] The position offered no salary, but provided Coolidge invaluable political experience.[18] In 1899, he declined renomination, running instead for City Solicitor, a position elected by the City Council. He was elected for a one-year term in 1900, and reelected in 1901.[19] This position gave Coolidge more experience as a lawyer and paid a salary of $600.[19] In 1902, the city council selected a Democrat for city solicitor, and Coolidge returned to private practice.[20] Soon thereafter, however, the clerk of courts for the county died, and Coolidge was chosen to replace him. The position paid well, but it barred him from practicing law, so he remained at the job for only one year.[20] In 1904, Coolidge suffered his sole defeat at the ballot box, losing an election to the Northampton school board. When told that some of his neighbors voted against him because he had no children in the schools he would govern, Coolidge replied, "Might give me time!"[20]

State legislator and mayor

In 1906, the local Republican committee nominated Coolidge for election to the state House of Representatives. He won a close victory over the incumbent Democrat, and reported to Boston for the 1907 session of the Massachusetts General Court.[21] In his freshman term, Coolidge served on minor committees and, although he usually voted with the party, was known as a Progressive Republican, voting in favor of such measures as women's suffrage and the direct election of Senators.[22] While in Boston, Coolidge became an ally, and then a liegeman, of then U.S. Senator Winthrop Murray Crane who controlled the western faction of the Massachusetts Republican Party; Crane's party rival in the east of the commonwealth was U.S. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge.[23] Another key strategic alliance which Coolidge forged was with Guy Currier, who had served in both state houses and had the social distinction, wealth, personal charm and broad circle of friends which Coolidge lacked, and which would have a lasting impact on his political career.[24] In 1907, he was elected to a second term, and in the 1908 session, Coolidge was more outspoken, though not in a leadership position.[25]

Instead of vying for another term in the State House, Coolidge returned home to his growing family and ran for mayor of Northampton when the incumbent Democrat retired. He was well liked in the town, and defeated his challenger by a vote of 1,597 to 1,409.[26] During his first term (1910 to 1911), he increased teachers' salaries and retired some of the city's debt while still managing to effect a slight tax decrease.[27] He was renominated in 1911, and defeated the same opponent by a slightly larger margin.[28]

In 1911, the State Senator for the Hampshire County area retired and successfully encouraged Coolidge to run for his seat for the 1912 session; Coolidge defeated his Democratic opponent by a large margin.[29] At the start of that term, he became chairman of a committee to arbitrate the "Bread and Roses" strike by the workers of the American Woolen Company in Lawrence, Massachusetts.[lower-alpha 1] After two tense months, the company agreed to the workers' demands, in a settlement proposed by the committee.[30] A major issue affecting Massachusetts Republicans that year was the party split between the progressive wing, which favored Theodore Roosevelt, and the conservative wing, which favored William Howard Taft. Although he favored some progressive measures, Coolidge refused to leave the Republican party.[31] When the new Progressive Party declined to run a candidate in his state senate district, Coolidge won reelection against his Democratic opponent by an increased margin.[31]

| Do the day's work. If it be to protect the rights of the weak, whoever objects, do it. If it be to help a powerful corporation better to serve the people, whatever the opposition, do that. Expect to be called a stand-patter, but don't be a stand-patter. Expect to be called a demagogue, but don't be a demagogue. Don't hesitate to be as revolutionary as science. Don't hesitate to be as reactionary as the multiplication table. Don't expect to build up the weak by pulling down the strong. Don't hurry to legislate. Give administration a chance to catch up with legislation. |

| Have Faith in Massachusetts as delivered by Calvin Coolidge to the Massachusetts State Senate, 1914.[32] |

In the 1913 session, Coolidge enjoyed renowned success in arduously navigating to passage the Western Trolley Act which connected Northampton with a dozen similar industrial communities in western Massachusetts.[33] Coolidge intended to retire after his second term as was the custom, but when the President of the State Senate, Levi H. Greenwood, considered running for Lieutenant Governor, Coolidge decided to run again for the Senate in the hopes of being elected as its presiding officer.[34] Although Greenwood later decided to run for reelection to the Senate, he was defeated primarily due to his opposition to women's suffrage; Coolidge was in favor of the women's vote, won his own re-election and with Crane's help, assumed the presidency of a closely divided Senate.[35] After his election in January 1914, Coolidge delivered a published and frequently quoted speech entitled Have Faith in Massachusetts, which summarized his philosophy of government.[32]

Coolidge's speech was well received, and he attracted some admirers on its account;[36] towards the end of the term, many of them were proposing his name for nomination to lieutenant governor. After winning reelection to the Senate by an increased margin in the 1914 elections, Coolidge was reelected unanimously to be President of the Senate.[37] Coolidge's supporters, led by fellow Amherst alumnus Frank Stearns, encouraged him again to run for lieutenant governor.[38] Stearns, an executive with the Boston department store R. H. Stearns, became another key ally, and began a publicity campaign on Coolidge's behalf before he announced his candidacy at the end of the 1915 legislative session.[39]

Lieutenant Governor and Governor of Massachusetts

Coolidge entered the primary election for lieutenant governor and was nominated to run alongside gubernatorial candidate Samuel W. McCall. Coolidge was the leading vote-getter in the Republican primary, and balanced the Republican ticket by adding a western presence to McCall's eastern base of support.[40] McCall and Coolidge won the 1915 election to their respective one-year terms, with Coolidge defeating his opponent by more than 50,000 votes.[41]

In Massachusetts, the lieutenant governor does not preside over the state Senate, as is the case in many other states; nevertheless, as lieutenant governor, Coolidge was a deputy governor functioning as administrative inspector and was a member of the governor's council. He was also chairman of the finance committee and the pardons committee.[42] As a full-time elected official, Coolidge discontinued his law practice in 1916, though his family continued to live in Northampton.[43] McCall and Coolidge were both reelected in 1916 and again in 1917. When McCall decided that he would not stand for a fourth term, Coolidge announced his intention to run for governor.[44]

1918 election

Coolidge was unopposed for the Republican nomination for Governor of Massachusetts in 1918. He and his running mate, Channing Cox, a Boston lawyer and Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, ran on the previous administration's record: fiscal conservatism, a vague opposition to Prohibition, support for women's suffrage, and support for American involvement in World War I.[45] The issue of the war proved divisive, especially among Irish and German Americans.[46] Coolidge was elected by a margin of 16,773 votes over his opponent, Richard H. Long, in the smallest margin of victory of any of his statewide campaigns.[47]

Boston Police Strike

In 1919, in reaction to a plan of the policemen of the Boston Police Department to register with a union, Police Commissioner Edwin U. Curtis announced that such an act would not be tolerated. In August of that year, the American Federation of Labor issued a charter to the Boston Police Union.[48] Curtis declared the union's leaders were guilty of insubordination and would be relieved of duty, but indicated he would cancel their suspension if the union was dissolved by September 4.[49] The mayor of Boston, Andrew Peters, convinced Curtis to delay his action for a few days, but with no results, and Curtis suspended the union leaders on September 8.[50] The following day, about three-quarters of the policemen in Boston went on strike.[51][lower-alpha 2] Coolidge, tacitly but fully in support of Curtis' position, closely monitored the situation but initially deferred to the local authorities. He anticipated that only a resulting measure of lawlessness could sufficiently prompt the public to understand and appreciate the controlling principle – that a policeman does not strike. That night and the next, there was sporadic violence and rioting in the unruly city.[52] Peters, concerned about sympathy strikes by the firemen and others, called up some units of the Massachusetts National Guard stationed in the Boston area pursuant to an old and obscure legal authority, and relieved Curtis of duty.[53]

| "Your assertion that the Commissioner was wrong cannot justify the wrong of leaving the city unguarded. That furnished the opportunity; the criminal element furnished the action. There is no right to strike against the public safety by anyone, anywhere, any time. ... I am equally determined to defend the sovereignty of Massachusetts and to maintain the authority and jurisdiction over her public officers where it has been placed by the Constitution and laws of her people." |

| Telegram from Governor Calvin Coolidge to Samuel Gompers September 14, 1919.[54] |

Coolidge, sensing the severity of circumstances were then in need of his intervention, conferred with Crane's operative, William Butler, and then acted.[55] He called up more units of the National Guard, restored Curtis to office, and took personal control of the police force.[56] Curtis proclaimed that all of the strikers were fired from their jobs, and Coolidge called for a new police force to be recruited.[57] That night Coolidge received a telegram from AFL leader Samuel Gompers. "Whatever disorder has occurred", Gompers wrote, "is due to Curtis's order in which the right of the policemen has been denied…"[58] Coolidge publicly answered Gompers's telegram, denying any justification whatsoever for the strike – and his response launched him into the national consciousness (quoted, above left).[58] Newspapers across the nation picked up on Coolidge's statement and he became the newest hero to opponents of the strike. In the midst of the First Red Scare, many Americans were terrified of the spread of communist revolution, like those that had taken place in Russia, Hungary, and Germany. While Coolidge had lost some friends among organized labor, conservatives across the nation had seen a rising star.[59] Although he usually acted with deliberation, the Boston police strike gave him a national reputation as a decisive leader, and as a strict enforcer of law and order.

1919 election

Coolidge and Cox were renominated for their respective offices in 1919. By this time Coolidge's supporters (especially Stearns) had publicized his actions in the Police Strike around the state and the nation and some of Coolidge's speeches were published in book form.[32] He faced the same opponent as in 1918, Richard Long, but this time Coolidge defeated him by 125,101 votes, more than seven times his margin of victory from a year earlier.[lower-alpha 3] His actions in the police strike, combined with the massive electoral victory, led to suggestions that Coolidge run for president in 1920.[61]

Legislation and vetoes as governor

By the time Coolidge was inaugurated on January 2, 1919, the First World War had ended, and Coolidge pushed the legislature to give a $100 bonus to Massachusetts veterans. He also signed a bill reducing the work week for women and children from fifty-four hours to forty-eight, saying, "We must humanize the industry, or the system will break down."[62] He signed into law a budget that kept the tax rates the same, while trimming $4 million from expenditures, thus allowing the state to retire some of its debt.[63]

Coolidge also wielded the veto pen as governor. His most publicized veto prevented an increase in legislators' pay by 50%.[64] Although Coolidge was personally opposed to Prohibition, he vetoed a bill in May 1920 that would have allowed the sale of beer or wine of 2.75% alcohol or less, in Massachusetts in violation of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. "Opinions and instructions do not outmatch the Constitution," he said in his veto message. "Against it, they are void."[65]

Vice presidency

1920 election

At the 1920 Republican National Convention, most of the delegates were selected by state party conventions, not primaries. As such, the field was divided among many local favorites.[66] Coolidge was one such candidate, and while he placed as high as sixth in the voting, the powerful party bosses running the convention, primarily the party's U.S. Senators, never considered him seriously.[67] After ten ballots, the bosses and then the delegates settled on Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio as their nominee for president.[68] When the time came to select a vice presidential nominee, the bosses also made and announced their decision on whom they wanted – Sen. Irvine Lenroot of Wisconsin – and then prematurely departed after his name was put forth, relying on the rank and file to confirm their decision. A delegate from Oregon, Wallace McCamant, having read Have Faith in Massachusetts, proposed Coolidge for vice president instead. The suggestion caught on quickly with the masses starving for an act of independence from the absent bosses, and Coolidge was unexpectedly nominated.[69]

The Democrats nominated another Ohioan, James M. Cox, for president and the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, for vice president. The question of the United States joining the League of Nations was a major issue in the campaign, as was the unfinished legacy of Progressivism.[70] Harding ran a "front-porch" campaign from his home in Marion, Ohio, but Coolidge took to the campaign trail in the Upper South, New York, and New England – his audiences carefully limited to those familiar with Coolidge and those placing a premium upon concise and short speeches.[71] On November 2, 1920, Harding and Coolidge were victorious in a landslide, winning more than 60 percent of the popular vote, including every state outside the South.[70] They also won in Tennessee, the first time a Republican ticket had won a Southern state since Reconstruction.[70]

"Silent Cal"

The U.S. vice presidency did not carry many official duties, but Coolidge was invited by President Harding to attend cabinet meetings, making him the first vice president to do so.[72] He gave a number of unremarkable speeches around the country.[73]

As the U.S. vice president, Coolidge and his vivacious wife Grace were invited to quite a few parties, where the legend of "Silent Cal" was born. It is from this time that most of the jokes and anecdotes involving Coolidge originate. Although Coolidge was known to be a skilled and effective public speaker, in private he was a man of few words and was commonly referred to as "Silent Cal". A possibly apocryphal story has it that a matron, seated next to him at a dinner, said to him, "I made a bet today that I could get more than two words out of you." He replied, "You lose."[74] Dorothy Parker, upon learning that Coolidge had died, reportedly remarked, "How can they tell?"[75] Coolidge often seemed uncomfortable among fashionable Washington society; when asked why he continued to attend so many of their dinner parties, he replied, "Got to eat somewhere."[76] Alice Roosevelt Longworth, a leading Republican wit, underscored Coolidge's silence and his dour personality: "When he wished he were elsewhere, he pursed his lips, folded his arms, and said nothing. He looked then precisely as though he had been weaned on a pickle."[77]

As president, Coolidge's reputation as a quiet man continued. "The words of a President have an enormous weight," he would later write, "and ought not to be used indiscriminately."[78] Coolidge was aware of his stiff reputation; indeed, he cultivated it. "I think the American people want a solemn ass as a President," he once told Ethel Barrymore, "and I think I will go along with them."[79] Some historians would later suggest that Coolidge's image was created deliberately as a campaign tactic,[80] while others believe his withdrawn and quiet behavior to be natural, deepening after the death of his son in 1924.[81]

Presidency

On August 2, 1923, President Harding died unexpectedly in San Francisco while on a speaking tour of the western United States. Vice President Coolidge was in Vermont visiting his family home, which had neither electricity nor a telephone, when he received word by messenger of Harding's death.[82] He dressed, said a prayer, and came downstairs to greet the reporters who had assembled.[82] His father, a notary public and justice of the peace, administered the oath of office in the family's parlor by the light of a kerosene lamp at 2:47 a.m. on August 3, 1923; President Coolidge then went back to bed.

Coolidge returned to Washington the next day, and was sworn in again by Justice Adolph A. Hoehling Jr. of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, to forestall any questions about the authority of a state official to administer a federal oath.[83] This second oath taking remained a secret until it was revealed by Harry M. Daugherty in 1932, and confirmed by Hoehling.[84] When Hoehling confirmed Daugherty's story, he indicated that Daugherty, then serving as United States Attorney General, asked him to administer the oath without fanfare at the Willard Hotel.[85] According to Hoehling, he did not question Daugherty's reason for requesting a second oath taking, but assumed it was to resolve any doubt about whether the first swearing in was valid.[85]

The nation initially did not know what to make of Coolidge, who had maintained a low profile in the Harding administration; many had even expected him to be replaced on the ballot in 1924.[86] Coolidge believed that those of Harding's men under suspicion were entitled to every presumption of innocence, taking a methodical approach to the scandals, principally the Teapot Dome scandal, while others clamored for rapid punishment of those they presumed guilty.[87] Coolidge thought the Senate investigations of the scandals would suffice; this was affirmed by the resulting resignations of those involved. He personally intervened in demanding the resignation of Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty after he refused to cooperate with the congressional probe. He then set about to confirm that no loose ends remained in the administration, arranging for a full briefing on the wrongdoing. Harry A. Slattery reviewed the facts with him, Harlan F. Stone analyzed the legal aspects for him and Senator William E. Borah assessed and presented the political factors.[88]

Coolidge addressed Congress when it reconvened on December 6, 1923, giving a speech that supported many of Harding's policies, including Harding's formal budgeting process, the enforcement of immigration restrictions and arbitration of coal strikes ongoing in Pennsylvania.[89] Coolidge's speech was the first presidential speech to be broadcast over the radio.[90] The Washington Naval Treaty was proclaimed just one month into Coolidge's term, and was generally well received in the country.[91] In May 1924, the World War I veterans' World War Adjusted Compensation Act or "Bonus Bill" was passed over his veto.[92] Coolidge signed the Immigration Act later that year, which was aimed at restricting southern and eastern European immigration, but appended a signing statement expressing his unhappiness with the bill's specific exclusion of Japanese immigrants.[93] Just before the Republican Convention began, Coolidge signed into law the Revenue Act of 1924, which reduced the top marginal tax rate from 58% to 46%, as well as personal income tax rates across the board, increased the estate tax and bolstered it with a new gift tax.[94]

On June 2, 1924, Coolidge signed the act granting citizenship to all Native Americans born in the United States. By that time, two-thirds of the people were already citizens, having gained it through marriage, military service (veterans of World War I were granted citizenship in 1919), or the land allotments that had earlier taken place.[95][96][97]

1924 election

The Republican Convention was held on June 10–12, 1924, in Cleveland, Ohio; Coolidge was nominated on the first ballot.[98] The convention nominated Frank Lowden of Illinois for vice president on the second ballot, but he declined; former Brigadier General Charles G. Dawes was nominated on the third ballot and accepted.[98]

The Democrats held their convention the next month in New York City. The convention soon deadlocked, and after 103 ballots, the delegates finally agreed on a compromise candidate, John W. Davis, with Charles W. Bryan nominated for vice president. The Democrats' hopes were buoyed when Robert M. La Follette Sr., a Republican senator from Wisconsin, split from the GOP to form a new Progressive Party. Many believed that the split in the Republican party, like the one in 1912, would allow a Democrat to win the presidency.[99]

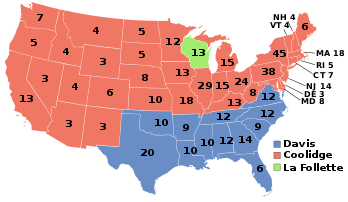

After the conventions and the death of his younger son Calvin, Coolidge became withdrawn; he later said that "when he [the son] died, the power and glory of the Presidency went with him."[100] Even as he mourned, Coolidge ran his standard campaign, not mentioning his opponents by name or maligning them, and delivering speeches on his theory of government, including several that were broadcast over radio.[101] It was the most subdued campaign since 1896, partly because of Coolidge's grief, but also because of his naturally non-confrontational style.[102] The other candidates campaigned in a more modern fashion, but despite the split in the Republican party, the results were similar to those of 1920. Coolidge and Dawes won every state outside the South except Wisconsin, La Follette's home state. Coolidge won the popular vote by 2.5 million over his opponents' combined total.[103]

Industry and trade

| it is probable that a press which maintains an intimate touch with the business currents of the nation is likely to be more reliable than it would be if it were a stranger to these influences. After all, the chief business of the American people is business. They are profoundly concerned with buying, selling, investing and prospering in the world. (emphasis added) |

| President Calvin Coolidge's address to the American Society of Newspaper Editors, Washington D.C., January 25, 1925.[104] |

During Coolidge's presidency, the United States experienced a period of rapid economic growth known as the "Roaring Twenties." He left the administration's industrial policy in the hands of his activist Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover, who energetically used government auspices to promote business efficiency and develop airlines and radio.[105] Coolidge disdained regulation, and demonstrated this by appointing commissioners to the Federal Trade Commission and the Interstate Commerce Commission who did little to restrict the activities of businesses under their jurisdiction.[106] The regulatory state under Coolidge was, as one biographer described it, "thin to the point of invisibility."[107]

Coolidge's economic policy has often been misquoted as "generally speaking, the business of the American people is business" (full quotation at right). Some have criticized Coolidge as an adherent of the laissez-faire ideology, which they claim led to the Great Depression.[108] On the other hand, historian Robert Sobel offers some context based on Coolidge's sense of federalism: "As Governor of Massachusetts, Coolidge supported wages and hours legislation, opposed child labor, imposed economic controls during World War I, favored safety measures in factories, and even worker representation on corporate boards. Did he support these measures while president? No, because in the 1920s, such matters were considered the responsibilities of state and local governments."[109][110]

Taxation and government spending

Coolidge's taxation policy was that of his Secretary of the Treasury, Andrew Mellon, the ideal that "scientific taxation"—lower taxes—actually increase rather than decrease government receipts.[111] Congress agreed, and the taxes were reduced in Coolidge's term.[111] In addition to these tax cuts, Coolidge proposed reductions in federal expenditures and retiring some of the federal debt.[112] Coolidge's ideas were shared by the Republicans in Congress, and in 1924, Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1924, which reduced income tax rates and eliminated all income taxation for some two million people.[112] They reduced taxes again by passing the Revenue Acts of 1926 and 1928, all the while continuing to keep spending down so as to reduce the overall federal debt.[113] By 1927, only the wealthiest 2% of taxpayers paid any federal income tax.[113] Federal spending remained flat during Coolidge's administration, allowing one-fourth of the federal debt to be retired in total. State and local governments saw considerable growth, however, surpassing the federal budget in 1927.[114]

Opposition to farm subsidies

Perhaps the most contentious issue of Coolidge's presidency was relief for farmers. Some in Congress proposed a bill designed to fight falling agricultural prices by allowing the federal government to purchase crops to sell abroad at lower prices.[115] Agriculture Secretary Henry C. Wallace and other administration officials favored the bill when it was introduced in 1924, but rising prices convinced many in Congress that the bill was unnecessary, and it was defeated just before the elections that year.[116] In 1926, with farm prices falling once more, Senator Charles L. McNary and Representative Gilbert N. Haugen—both Republicans—proposed the McNary–Haugen Farm Relief Bill. The bill proposed a federal farm board that would purchase surplus production in high-yield years and hold it (when feasible) for later sale or sell it abroad.[117] Coolidge opposed McNary-Haugen, declaring that agriculture must stand "on an independent business basis," and said that "government control cannot be divorced from political control."[117] Instead of manipulating prices, he favored instead Herbert Hoover's proposal to create profits by modernizing agriculture. Secretary Mellon wrote a letter denouncing the McNary-Haugen measure as unsound and likely to cause inflation, and it was defeated.[118]

After McNary-Haugen's defeat, Coolidge supported a less radical measure, the Curtis-Crisp Act, which would have created a federal board to lend money to farm co-operatives in times of surplus; the bill did not pass.[118] In February 1927, Congress took up the McNary-Haugen bill again, this time narrowly passing it, and Coolidge vetoed it.[119] In his veto message, he expressed the belief that the bill would do nothing to help farmers, benefiting only exporters and expanding the federal bureaucracy.[120] Congress did not override the veto, but it passed the bill again in May 1928 by an increased majority; again, Coolidge vetoed it.[119] "Farmers never have made much money," said Coolidge, the Vermont farmer's son. "I do not believe we can do much about it."[121]

Flood control

Coolidge has often been criticized for his actions during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the worst natural disaster to hit the Gulf Coast until Hurricane Katrina in 2005.[122] Although he did eventually name Secretary Hoover to a commission in charge of flood relief, scholars argue that Coolidge overall showed a lack of interest in federal flood control.[122] Coolidge did not believe that personally visiting the region after the floods would accomplish anything, and that it would be seen as mere political grandstanding. He also did not want to incur the federal spending that flood control would require; he believed property owners should bear much of the cost.[123] On the other hand, Congress wanted a bill that would place the federal government completely in charge of flood mitigation.[124] When Congress passed a compromise measure in 1928, Coolidge declined to take credit for it and signed the bill in private on May 15.[125]

Minorities

According to one biographer, Coolidge was "devoid of racial prejudice," but rarely took the lead on civil rights. Coolidge disliked the Ku Klux Klan and no Klansman is known to have received an appointment from him. In the 1924 presidential election his opponents (Robert La Follette and John Davis), and his running mate Charles Dawes, often attacked the Klan but Coolidge avoided the subject, just as he avoided most controversial topics.[126]

Coolidge spoke in favor of the civil rights of African-Americans, saying in his first State of the Union address that their rights were "just as sacred as those of any other citizen" under the U.S. Constitution and that it was a "public and a private duty to protect those rights."[127][128]

Coolidge repeatedly called for laws to make lynching a federal crime (it was already a state crime). Congress refused to pass any such legislation. On June 2, 1924, Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act, which granted U.S. citizenship to all American Indians living on reservations (Indians off reservations had long been citizens). [129] On June 6, 1924, Coolidge delivered a commencement address at historically black, non-segregated Howard University, in which he thanked and commended African-Americans for their rapid advances in education and their contributions to U.S. society over the years, as well as their eagerness to render their services as soldiers in the World War, all while being faced with discrimination and prejudices at home.[130]

In a speech in October 1924, Coolidge stressed tolerance of differences as an American value and thanked immigrants for their contributions to U.S. society, saying that they have "contributed much to making our country what it is." He stated that although the diversity of peoples was a detrimental source of conflict and tension in Europe, it was peculiar for the United States that it was a "harmonious" benefit for the country. Coolidge further stated the United States should assist and help immigrants who come to the country, and urged immigrants to reject "race hatreds" and "prejudices".[131]

Foreign policy

Although not an isolationist, Coolidge was reluctant to enter into foreign alliances.[132] He considered the 1920 Republican victory as a rejection of the Wilsonian position that the United States should join the League of Nations.[133] While not completely opposed to the idea, Coolidge believed the League, as then constituted, did not serve American interests, and he did not advocate membership.[133] He spoke in favor of the United States joining the Permanent Court of International Justice (World Court), provided that the nation would not be bound by advisory decisions.[134] In 1926, the Senate eventually approved joining the Court (with reservations).[135] The League of Nations accepted the reservations, but it suggested some modifications of its own.[136] The Senate failed to act; the United States never joined the World Court.[136]

Coolidge's primary initiative was the Kellogg–Briand Pact of 1928, named for Coolidge's Secretary of State, Frank B. Kellogg, and French foreign minister Aristide Briand. The treaty, ratified in 1929, committed signatories—the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan—to "renounce war, as an instrument of national policy in their relations with one another."[137] The treaty did not achieve its intended result—the outlawry of war—but it did provide the founding principle for international law after World War II.[138]

Coolidge continued the previous administration's policy of withholding recognition of the Soviet Union.[139] He also continued the United States' support for the elected government of Mexico against the rebels there, lifting the arms embargo on that country.[140] He sent Dwight Morrow to Mexico as the American ambassador.[141]

The United States' occupation of Nicaragua and Haiti continued under his administration, but Coolidge withdrew American troops from the Dominican Republic in 1924.[142] Coolidge led the U.S. delegation to the Sixth International Conference of American States, January 15–17, 1928, in Havana, Cuba. This was the only international trip Coolidge made during his presidency.[143] There, he extended an olive branch to Latin American leaders embittered over America's interventionist policies in Central America and the Caribbean.[144] For 88 years he was the only sitting president to have visited Cuba, until Barack Obama did so in 2016.[145]

1928 election

In the summer of 1927, Coolidge vacationed in the Black Hills of South Dakota, where he engaged in horseback riding and fly fishing and attended rodeos. He made Custer State Park his "summer White House." While on vacation, Coolidge surprisingly issued a terse statement that he would not seek a second full term as president: "I do not choose to run for President in 1928."[146] After allowing the reporters to take that in, Coolidge elaborated. "If I take another term, I will be in the White House till 1933 … Ten years in Washington is longer than any other man has had it—too long!"[147] In his memoirs, Coolidge explained his decision not to run: "The Presidential office takes a heavy toll of those who occupy it and those who are dear to them. While we should not refuse to spend and be spent in the service of our country, it is hazardous to attempt what we feel is beyond our strength to accomplish."[148] After leaving office, he and Grace returned to Northampton, where he wrote his memoirs. The Republicans retained the White House in 1928 in the person of Coolidge's Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover. Coolidge had been reluctant to endorse Hoover as his successor; on one occasion he remarked that "for six years that man has given me unsolicited advice—all of it bad."[149] Even so, Coolidge had no desire to split the party by publicly opposing the nomination of the popular commerce secretary.[150]

Cabinet

Front row, left to right: Harry Stewart New, John W. Weeks, Charles Evans Hughes, Coolidge, Andrew Mellon, Harlan F. Stone, Curtis D. Wilbur

Back row, left to right, James J. Davis, Henry C. Wallace, Herbert Hoover, Hubert Work

Although a few of Harding's cabinet appointees were scandal-tarred, Coolidge initially retained all of them, out of an ardent conviction that as successor to a deceased elected president he was obligated to retain Harding's counselors and policies until the next election. He kept Harding's able speechwriter Judson T. Welliver; Stuart Crawford replaced Welliver in November 1925.[151] Coolidge appointed C. Bascom Slemp, a Virginia Congressman and experienced federal politician, to work jointly with Edward T. Clark, a Massachusetts Republican organizer whom he retained from his vice-presidential staff, as Secretaries to the President (a position equivalent to the modern White House Chief of Staff).[91]

Perhaps the most powerful person in Coolidge's Cabinet was Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon, who controlled the administration's financial policies and was regarded by many, including House Minority Leader John Nance Garner, as more powerful than Coolidge himself.[152] Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover also held a prominent place in Coolidge's Cabinet, in part because Coolidge found value in Hoover's ability to win positive publicity with his pro-business proposals.[153] Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes directed Coolidge's foreign policy until he resigned in 1925 following Coolidge's re-election. He was replaced by Frank B. Kellogg, who had previously served as a Senator and as the ambassador to Great Britain. Coolidge made two other appointments following his re-election, with William M. Jardine taking the position of Secretary of Agriculture and John G. Sargent becoming Attorney General.[154] Coolidge did not have a vice president during his first term, but Charles Dawes became vice president during Coolidge's second term, and Dawes and Coolidge clashed over farm policy and other issues.[155]

Judicial appointments

Coolidge appointed one justice to the Supreme Court of the United States, Harlan Fiske Stone in 1925. Stone was Coolidge's fellow Amherst alumnus, a Wall Street lawyer and conservative Republican. Stone was serving as dean of Columbia Law School when Coolidge appointed him to be attorney general in 1924 to restore the reputation tarnished by Harding's Attorney General, Harry M. Daugherty.[156] Stone proved to be a firm believer in judicial restraint and was regarded as one of the court's three liberal justices who would often vote to uphold New Deal legislation.[157] President Franklin D. Roosevelt later appointed Stone to be chief justice.

Coolidge nominated 17 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 61 judges to the United States district courts. He appointed judges to various specialty courts as well, including Genevieve R. Cline, who became the first woman named to the federal judiciary when Coolidge placed her on the United States Customs Court in 1928.[158] Coolidge also signed the Judiciary Act of 1925 into law, allowing the Supreme Court more discretion over its workload.

Retirement and death

After his presidency, Coolidge retired to the modest rented house on residential Massasoit Street in Northampton before moving to a more spacious home, "The Beeches."[159] He kept a Hacker runabout boat on the Connecticut River and was often observed on the water by local boating enthusiasts. During this period, he also served as chairman of the non-partisan Railroad Commission, as honorary president of the American Foundation for the Blind, as a director of New York Life Insurance Company, as president of the American Antiquarian Society, and as a trustee of Amherst College.[160]

Coolidge published his autobiography in 1929 and wrote a syndicated newspaper column, "Calvin Coolidge Says," from 1930 to 1931.[161] Faced with looming defeat in the 1932 presidential election, some Republicans spoke of rejecting Herbert Hoover as their party's nominee, and instead drafting Coolidge to run, but the former president made it clear that he was not interested in running again, and that he would publicly repudiate any effort to draft him, should it come about.[162] Hoover was renominated, and Coolidge made several radio addresses in support of him. Hoover then lost the general election to Coolidge's 1920 vice presidential Democratic opponent Franklin D. Roosevelt in a landslide[163]

Coolidge died suddenly from coronary thrombosis at "The Beeches," at 12:45 p.m., January 5, 1933.[164] Shortly before his death, Coolidge confided to an old friend: "I feel I no longer fit in with these times."[165] Coolidge is buried in Plymouth Notch Cemetery, Plymouth Notch, Vermont. The nearby family home is maintained as one of the original buildings on the Calvin Coolidge Homestead District site. The State of Vermont dedicated a new visitors' center nearby to mark Coolidge's 100th birthday on July 4, 1972.

Radio, film, and commemorations

Despite his reputation as a quiet and even reclusive politician, Coolidge made use of the new medium of radio and made radio history several times while president. He made himself available to reporters, giving 520 press conferences, meeting with reporters more regularly than any president before or since.[166] Coolidge's second inauguration was the first presidential inauguration broadcast on radio. On December 6, 1923, he was the first president whose address to Congress was broadcast on radio.[167] Coolidge signed the Radio Act of 1927, which assigned regulation of radio to the newly created Federal Radio Commission. On August 11, 1924, Theodore W. Case, using the Phonofilm sound-on-film process he developed for Lee DeForest, filmed Coolidge on the White House lawn, making Coolidge the first president to appear in a sound film. The title of the DeForest film was President Coolidge, Taken on the White House Grounds.[168] When Charles Lindbergh arrived in Washington on a U.S. Navy ship after his celebrated 1927 trans-Atlantic flight, President Coolidge welcomed him back to the U.S. and a sound-on-film record of the event exists.

Coolidge was the only president to have his portrait on a coin during his lifetime, the Sesquicentennial of American Independence Half Dollar, minted in 1926.

Coolidge was the only president to have his portrait on a coin during his lifetime, the Sesquicentennial of American Independence Half Dollar, minted in 1926. Coolidge on a 1938 postage stamp

Coolidge on a 1938 postage stamp

See also

- SS President Coolidge

- Coolidge, Arizona

- Coolidge Dam

- Coolidge effect

- List of Presidents of the United States

- List of Presidents of the United States, sortable by previous experience

Notes

References

- ↑ McCoy 1967, pp. 420–21; Greenberg 2006, pp. 49–53.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 500.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, pp. 12–13; Greenberg 2006, pp. 1–7.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 22.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 17; McCoy 1967, p. 5; White 1938, p. 11.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 12.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 7.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 24.

- ↑ White 1938, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Shlaes 2013, pp. 66–68.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 74–81; McCoy 1967, pp. 22–26.

- ↑ Bryson 2013, p. 187.

- ↑ White 1938, p. 61.

- ↑ Martin, Douglas (June 4, 2000). "John Coolidge, Guardian of President's Legacy. Dies at 93". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-25.

- ↑ Shlaes 2013, p. 91.

- 1 2 Sobel 1998, pp. 49–51.

- ↑ White 1938, pp. 51–53.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 83.

- 1 2 Fuess 1940, pp. 84–85.

- 1 2 3 McCoy 1967, p. 29.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 61.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 62; Fuess 1940, p. 99.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, pp. 63–66.

- ↑ White 1938, pp. 99–102.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 72.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 106–07; Sobel 1998, p. 74.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 108.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 76.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 110–11; McCoy 1967, pp. 45–46.

- 1 2 Sobel 1998, pp. 79–80; Fuess 1940, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 Coolidge 1919, pp. 2–9.

- ↑ White 1938, p. 105.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 114–15.

- ↑ White 1938, p. 111.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, pp. 90–92.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 90; Fuess 1940, p. 124.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, pp. 92–98; Fuess 1940, pp. 133–36.

- ↑ White 1938, p. 117.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 139–142.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 145.

- ↑ White 1938, p. 125.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 151–52.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, pp. 107–110.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 111; McCoy 1967, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 112.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 115; McCoy 1967, p. 76.

- ↑ Russell 1975, pp. 77–79; Sobel 1998, p. 129.

- ↑ Russell 1975, p. 86–87.

- ↑ Russell 1975, pp. 111–13; Sobel 1998, pp. 133–36.

- 1 2 Russell 1975, p. 113.

- ↑ White 1938, pp. 162–164.

- ↑ Russell 1975, p. 120.

- ↑ Coolidge 1919, pp. 222–24.

- ↑ White 1938, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 142.

- ↑ Russell 1975, pp. 182–83.

- 1 2 Sobel 1998, p. 143.

- ↑ Shlaes 2013, pp. 174–79.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 238.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 239–43; McCoy 1967, pp. 102–13.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 117; Fuess 1940, p. 195.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 186.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 187; McCoy 1967, p. 81.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 187–88.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, pp. 152–53.

- ↑ White 1938, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 259–60.

- ↑ White 1938, pp. 211–213.

- 1 2 3 Sobel 1998, pp. 204–12.

- ↑ White 1938, pp. 217–219.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, pp. 210–11.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 219; McCoy 1967, p. 136.

- ↑ Hannaford, p. 169.

- ↑ Greenberg 2006, p. 9.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 217.

- ↑ Cordery 2008, p. 302.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 243.

- ↑ Greenberg 2006, p. 60.

- ↑ Buckley, pp. 593–626.

- ↑ Gilbert, pp. 87–109.

- 1 2 Fuess 1940, pp. 308–09.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 310–15.

- ↑ "Confirms Daugherty's Story of Coolidge's Second Oath". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, MO. Associated Press. February 2, 1932. p. 1C. (Subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 "Confirms Daugherty's Story of Coolidge's Second Oath".

- ↑ Sobel 1998, pp. 226–28; Fuess 1940, pp. 303–05; Ferrell 1998, pp. 43–51.

- ↑ White 1938, p. 265.

- ↑ White 1938, pp. 272–277.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 328–29; Sobel 1998, pp. 248–49.

- ↑ Shlaes 2013, p. 271.

- 1 2 Fuess 1940, pp. 320–22.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 341.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 342; Sobel 1998, p. 269.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, pp. 278–79.

- ↑ Madsen, Deborah L., ed. (2015). The Routledge Companion to Native American Literature. Routledge. p. 168. ISBN 1317693191.

- ↑ Charles Kappler (1929). "Indian affairs: laws and treaties Vol. IV, Treaties". Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- ↑ Alysa Landry, "Calvin Coolidge: First Sitting Prez Adopted by Tribe Starts Desecration of Mount Rushmore", Indian Country Today, 26 July 2016; accessed same day

- 1 2 Fuess 1940, pp. 345–46.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 300.

- ↑ Coolidge 1929, p. 190.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, pp. 300–01.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, pp. 302–03.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 354.

- ↑ Shlaes 2013, p. 324.

- ↑ Ferrell 1998, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Ferrell 1998, pp. 66–72; Sobel 1998, p. 318.

- ↑ Ferrell 1998, p. 72.

- ↑ Ferrell 1998, p. 207.

- ↑ Sobel, Robert. "Coolidge and American Business". John F. Kennedy Library and Museum. Archived from the original on March 8, 2006.

- ↑ Greenberg 2006, p. 47; Ferrell 1998, p. 62.

- 1 2 Sobel 1998, pp. 310–11; Greenberg 2006, pp. 127–29.

- 1 2 Sobel 1998, pp. 310–11; Fuess 1940, pp. 382–83.

- 1 2 Ferrell 1998, p. 170.

- ↑ Ferrell 1998, p. 174.

- ↑ Ferrell 1998, p. 84; McCoy 1967, pp. 234–35.

- ↑ McCoy 1967, p. 235.

- 1 2 Fuess 1940, pp. 383–84.

- 1 2 Sobel 1998, p. 327.

- 1 2 Fuess 1940, p. 388; Ferrell 1998, p. 93.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 331.

- ↑ Ferrell 1998, p. 86.

- 1 2 Sobel 1998, p. 315; Barry 1997, pp. 286–87; Greenberg 2006, pp. 132–35.

- ↑ McCoy 1967, pp. 330–31.

- ↑ Barry 1997, pp. 372–74.

- ↑ Greenberg 2006, p. 135.

- ↑ Roberts 2014, p. 209.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 250; McCoy 1967, pp. 328–29.

- ↑ Wikisource:Calvin Coolidge's First State of the Union Address

- ↑ Deloria 1992, p. 91.

- ↑ Coolidge 1926, pp. 31–36.

- ↑ Coolidge 1926, pp. 159–156.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 342.

- 1 2 McCoy 1967, pp. 184–85.

- ↑ McCoy 1967, p. 360.

- ↑ McCoy 1967, p. 363.

- 1 2 Greenberg 2006, pp. 114–16.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 421–23.

- ↑ McCoy 1967, pp. 380–81; Greenberg 2006, pp. 123–24.

- ↑ McCoy 1967, p. 181.

- ↑ McCoy 1967, pp. 178–79.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 349.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 414–17; Ferrell 1998, pp. 122–23.

- ↑ "Travels of President Calvin Coolidge". U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian.

- ↑ "Calvin Coolidge: Foreign Affairs". millercenter.org. Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on February 20, 2016. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ↑ Kim, Susanna (December 18, 2014). "Here's What Happened the Last Time a US President Visited Cuba". ABC News. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 370.

- ↑ White 1938, p. 361.

- ↑ Coolidge 1929, p. 239.

- ↑ Ferrell 1998, p. 195.

- ↑ McCoy 1967, pp. 390–91; Wilson 1975, pp. 122–23.

- ↑ Greenberg 2006, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Rusnak 1983, pp. 270-271.

- ↑ Polsky & Tkacheva 2002, pp. 224-227.

- ↑ Greenberg 2006, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ "Charles G. Dawes, 30th Vice President (1925-1929)". US Senate. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 364.

- ↑ Galston, passim.

- ↑ Freeman 2002, p. 216.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 407.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 450–55.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 403; Ferrell 1998, pp. 201–02.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, pp. 457–59; Greenberg 2006, p. 153.

- ↑ Fuess 1940, p. 460.

- ↑ Greenberg 2006, pp. 154–55.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 410.

- ↑ Greenberg 2006, p. 7.

- ↑ Sobel 1998, p. 252.

- ↑ "President Coolidge, Taken on the White House Ground (1924)". Retrieved February 4, 2007.

Works cited

Scholarly sources

- Barry, John M. (1997). Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-84002-4.

- Bryson, Bill (2013), One Summer: America, 1927, New York: Doubleday, ISBN 978-0-7679-1940-1

- Cordery, Stacy A. (2008). Alice: Alice Roosevelt Longworth, from White House Princess to Washington Power Broker. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-311427-1.

- Deloria, Vincent (1992). American Indian Policy in the Twentieth Century. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2424-7.

- Ferrell, Robert H. (1998). The Presidency of Calvin Coolidge. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0892-8.

- Freeman, Jo (2002). A Room at a Time: How Women Entered Party Politics. Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-9805-9.

- Fuess, Claude M. (1940). Calvin Coolidge: The Man from Vermont. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4067-5673-9.

- Greenberg, David (2006). Calvin Coolidge. The American Presidents Series. Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-6957-0.

- McCoy, Donald R. (1967). Calvin Coolidge: The Quiet President. Macmillan. ISBN 1468017772.

- Russell, Francis (1975). A City in Terror: Calvin Coolidge and the 1919 Boston Police Strike. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-5033-0.

- Shlaes, Amity (2013). Coolidge. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-196755-9.

- Sobel, Robert (1998). Coolidge: An American Enigma. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89526-410-7.

- White, William Allen (1938). A Puritan in Babylon: The Story of Calvin Coolidge. Macmillan.

- Wilson, Joan Hoff (1975). Herbert Hoover, Forgotten Progressive. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-94416-8.

Articles and book chapters

- Buckley, Kerry W. (December 2003). "'A President for the "Great Silent Majority': Bruce Barton's Construction of Calvin Coolidge". The New England Quarterly. 76 (4): 593–626. JSTOR 1559844. doi:10.2307/1559844.

- Galston, Miriam (November 1995). "Activism and Restraint: The Evolution of Harlan Fiske Stone's Judicial Philosophy". Tulane Law Revue. 70: 137.

- Gilbert, Robert E. (2005). "Calvin Coolidge's Tragic Presidency: the Political Effects of Bereavement and Depression". Journal of American Studies. 39 (1): 87–109. JSTOR 27557598. doi:10.1017/S0021875805009266.

- Polsky, Andrew J.; Tkacheva, Olesya (Winter 2002). "Legacies versus Politics: Herbert Hoover, Partisan Conflict, and the Symbolic Appeal of Associationalism in the 1920s". International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. 16 (2): 207–235. JSTOR 20020160.

- Roberts, Jason (2014). "The Biographical Legacy of Calvin Coolidge and the 1924 Presidential Election". In Katherine A. S. Sibley. A Companion to Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover. Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-83447-3.

- Rusnak, Robert J. (Spring 1983). "Andrew W. Mellon: Reluctant Kingmaker". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 13 (2): 269–278. JSTOR 27547924.

Primary sources

- Coolidge, Calvin (1919). Have Faith in Massachusetts: A Collection of Speeches and Messages (2nd ed.). Houghton Mifflin.

- Coolidge, Calvin (2004) [1926]. Foundations of the Republic: Speeches and Addresses. University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 1-4102-1598-9.

- Coolidge, Calvin (1929). The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge. Cosmopolitan Book Corp. ISBN 0-944951-03-1.

- Coolidge, Calvin (2001). Peter Hannaford, ed. The Quotable Calvin Coolidge: Sensible Words for a New Century. Images From The Past, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-884592-33-1.

Further reading

- Coolidge, Calvin (1964). Howard H. Quint and Robert H. Ferrell, ed. The Talkative President: The Off-the Record Press Conferences of Calvin Coolidge. University of Massachusetts Press.

- Felzenberg, Alvin S. (Fall 1998). "Calvin Coolidge and Race: His Record in Dealing with the Racial Tensions of the 1920s". New England Journal of History. 55 (1): 83–96.

- Hatfield, Mark O. (1997). "Calvin Coolidge (1921–1923)". Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 347–354.

External links

| Library resources about Calvin Coolidge |

| By Calvin Coolidge |

|---|

- White House biography

- United States Congress. "Calvin Coolidge (id: C000738)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Calvin Coolidge Presidential Library & Museum

- Calvin Coolidge Presidential Foundation

- Text of a number of Coolidge speeches, Miller Center of Public Affairs

- "Calvin Coolidge collected news and commentary". The New York Times.

- Calvin Coolidge: A Resource Guide, Library of Congress

- Works by or about Calvin Coolidge at Internet Archive

- President Coolidge, Taken on the White House Ground, the first presidential film with sound recording

- Calvin Coolidge at DMOZ

- "Life Portrait of Calvin Coolidge", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, September 27, 1999

- Calvin Coolidge Personal Manuscripts

- Calvin Coolidge on IMDb