Jin Chinese

| Jin | |

|---|---|

| 晉語 / 晋语 | |

|

Jinyu written in Chinese characters | |

| Native to | China |

| Region | most of Shanxi province; central Inner Mongolia; parts of Hebei, Henan, Shaanxi |

Native speakers | 48 million (2007)[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

cjy |

| Glottolog |

jiny1235[2] |

| Linguasphere |

79-AAA-c |

| |

| Jin Chinese | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 晉語 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 晋语 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 山西話 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 山西话 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Shanxi speech | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

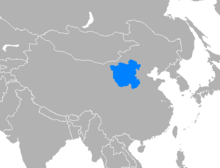

Jin (simplified Chinese: 晋语; traditional Chinese: 晉語; pinyin: jìnyǔ) is a group of Chinese spoken by roughly 45 million people in northern China. Its geographical distribution covers most of Shanxi province except for the lower Fen River valley, much of central Inner Mongolia and adjoining areas in Hebei, Henan, and Shaanxi provinces. The status of Jin is disputed among linguists; some prefer to classify it under Mandarin, but others set it apart as an independent branch.

Classification

Until the 1980s, Jin was universally considered to be a dialect of Mandarin Chinese. In 1985, however, Li Rong proposed that Jin should be considered a separate top-level grouping, similar to Cantonese or Wu Chinese (that is, its own dialect group). His main criterion was that Jin dialects had preserved the entering tone as a separate category, still marked with a glottal stop as in the Wu dialects, but distinct in this respect from the other Mandarin dialects.

Other linguists have subsequently adopted this classification. However, some linguists still do not agree that Jin should be considered a separate dialect group[3] for these reasons:

- Languages and dialect groups are not normally delineated based on a single feature but rather on a cluster of features distinguishing the group from other related varieties as well as mutual intelligibility. Use of a single diagnostic feature is inconsistent with the way that all other Chinese dialect groups have been delineated.[3]

- Certain other Mandarin dialects also preserve the glottal stop, especially the Jianghuai dialects, and so far, no linguist has claimed that these dialects should also be split from Mandarin.[3]

Dialects

Jin can be divided into the following 8 subdivisions:[4]

- Bingzhou, or that spoken in central Shanxi, including Taiyuan

- Lüliang, or that spoken in western Shanxi and northern Shaanxi

- Shangdang, or that spoken in southeastern Shanxi

- Wutai, or that spoken in parts of northern Shanxi and central Inner Mongolia

- Datong–Baotou, or that spoken in parts of northern Shanxi and central Inner Mongolia

- Zhangjiakou–Hohhot, or that spoken in northwestern Hebei and parts of central Inner Mongolia

- Handan–Xinxiang, or that spoken in southeastern Shanxi, southern Hebei and northern Henan

- Zhidan–Yanchuan (志丹-延川)

Phonology

Unlike most varieties of Mandarin, Jin has preserved a final glottal stop, which is the remnant of a final stop consonant (/p/, /t/ or /k/). This is in common with the Early Mandarin of the Yuan Dynasty (c. 14th century AD) and with a number of modern southern varieties of Chinese. In Middle Chinese, syllables closed with a stop consonant had no tone; Chinese linguists, however, prefer to categorize such syllables as belonging to a separate tone class, traditionally called the "entering tone". Syllables closed with a glottal stop in Jin are still toneless, or alternatively, Jin can be said to still maintain the entering tone. (In standard Mandarin Chinese, syllables formerly ending with a glottal stop have been reassigned to one of the other tone classes in a seemingly random fashion.)

Jin employs extremely complex tone sandhi, or tone changes that occur when words are put together into phrases. The tone sandhi of Jin is notable in two ways among Chinese varieties:

- Tone sandhi rules depend on the grammatical structure of the words being put together. Hence, an adjective–noun compound may go through different sets of changes compared to a verb–object compound.

- There are tones that merge when words are pronounced alone, but behave differently (and hence are differentiated) during tone sandhi.

Grammar

Jin readily employs prefixes such as 圪 /kəʔ/, 忽 /xəʔ/, and 入 /zəʔ/, in a variety of derivational constructions. For example:

入鬼 "fool around" < 鬼 "ghost, devil"

In addition, there are a number of words in Jin that evolved, evidently, by splitting a mono-syllabic word into two, adding an 'l' in between (cf. Ubbi Dubbi, but with /l/ instead of /b/). For example:

/pəʔ ləŋ/ < 蹦 pəŋ "hop"

/tʰəʔ luɤ/ < 拖 tʰuɤ "drag"

/kuəʔ la/ < 刮 kua "scrape"

/xəʔ lɒ̃/ < 巷 xɒ̃ "street"

A similar process can in fact be found in most Mandarin dialects (e.g. 窟窿 kulong < 孔 kong), but it is especially common in Jin.

Vocabulary

Some dialects of Jin make a three-way distinction in demonstratives. (Modern English, for example, has only a two-way distinction between "this" and "that", with "yonder" being archaic.)

Notes

- ↑ Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Jinyu Chinese". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- 1 2 3 Kurpaska 2010, pp. 74–75

- ↑ Kurpaska 2010, p. 68

References

- Hou Jingyi 侯精一; Shen Ming 沈明 (2002), Hou Jingyi 侯精一, ed., 现代汉语方言概论 [Overview of modern Chinese dialects] (in Chinese), Shanghai Education Press, ISBN 7-5320-8084-6

- Kurpaska, Maria (2010), Chinese Language(s): A Look Through the Prism of The Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-021914-2