Jim Jarmusch

| Jim Jarmusch | |

|---|---|

|

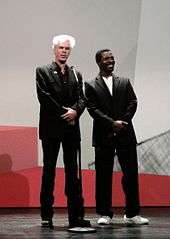

Jarmusch at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival | |

| Born |

James Robert Jarmusch[1] January 22, 1953 Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, United States |

| Occupation | Filmmaker, Actor, Composer |

| Years active | 1979–present |

| Partner(s) | Sara Driver |

James Robert Jarmusch (/ˈdʒɑːrməʃ/;[2] born January 22, 1953) is an American film director, screenwriter, actor, producer, editor, and composer.[3] He has been a major proponent of independent cinema since the 1980s, directing such films as Stranger Than Paradise (1984), Down by Law (1986), Mystery Train (1989), Dead Man (1995), Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999), Coffee and Cigarettes (2003), Broken Flowers (2005), Only Lovers Left Alive (2013), and Paterson (2016).[4] Stranger Than Paradise was added to the National Film Registry in December 2002.[5] As a musician, Jarmusch has composed music for his films and released two albums with Jozef van Wissem.

Early life

Tom Waits, as quoted in The New York Times, 2005.[6]

Jarmusch was born in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, the middle of three children of middle-class suburbanites.[4][6][7][8] His mother, of German and Irish descent, had been a reviewer of film and theatre for the Akron Beacon Journal before marrying his father, a businessman of Czech and German descent who worked for the B.F. Goodrich Company.[7][9][10] She introduced Jarmusch to the world of cinema by leaving him at a local cinema to watch matinee double features such as Attack of the Crab Monsters and Creature From the Black Lagoon while she ran errands.[11][12] The first adult film he recalls seeing was the 1958 cult classic Thunder Road, the violence and darkness of which left an impression on the seven-year-old Jarmusch.[13] Another B-movie influence from his childhood was Ghoulardi, an eccentric Cleveland television show which featured horror films.[12]

Despite his enthusiasm for film, Jarmusch was an avid reader in his youth[4] and had a greater interest in literature, which was encouraged by his grandmother.[9] Though he refused to attend church with his Episcopalian parents (not being enthused by "the idea of sitting in a stuffy room wearing a little tie"), Jarmusch credits literature with shaping his metaphysical beliefs and leading him to reconsider theology in his mid-teens.[13] From his peers he developed a taste for counterculture, and he and his friends would steal the records and books of their older siblings – this included works by William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, and The Mothers of Invention.[4][14] They made fake identity documents which allowed them to visit bars at the weekend but also the local art house cinema, which typically showed pornographic films but would occasionally feature underground films such as Robert Downey, Sr.'s Putney Swope and Andy Warhol's Chelsea Girls.[4][14] At one point, he took an apprenticeship with a commercial photographer.[4] He later remarked, "Growing up in Ohio was just planning to get out."[14]

After graduating from high school in 1971,[15] Jarmusch moved to Chicago and enrolled in the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.[8][16] After being asked to leave due to neglecting to take any journalism courses – Jarmusch favored literature and art history – he transferred to Columbia University the following year, with the intention of becoming a poet.[13][16] At Columbia, he studied English and American literature under professors including New York School avant garde poets Kenneth Koch and David Shapiro.[9] At Columbia, he began to write short "semi-narrative abstract pieces"[9] and edited the undergraduate literary journal The Columbia Review.[8][17]

During his final year at Columbia, Jarmusch moved to Paris for what was initially a summer semester on an exchange program, but this turned into ten months.[4][15] There, he worked as a delivery driver for an art gallery, and spent most of his time at the Cinémathèque Française.[4][8]

That's where I saw things I had only read about and heard about – films by many of the good Japanese directors, like Imamura, Ozu, Mizoguchi. Also, films by European directors like Bresson and Dreyer, and even American films, like the retrospective of Samuel Fuller’s films, which I only knew from seeing a few of them on television late at night. When I came back from Paris, I was still writing, and my writing was becoming more cinematic in certain ways, more visually descriptive.— Jarmusch on the Cinémathèque Française, taken from an interview with Lawrence Van Gelder of The New York Times, October 21, 1984.[9]

Jarmusch graduated from Columbia University in 1975.[8] Broke and working as a musician in New York City after returning from Paris in 1976, he applied on a whim to the prestigious Graduate Film School of New York University's Tisch School of the Arts (then under the direction of Hollywood director László Benedek).[9][4][16] Despite his lack of experience in filmmaking, his submission of a collection of photographs and an essay about film secured his acceptance into the program.[9] He studied there for four years, meeting fellow students and future collaborators Sara Driver, Tom DiCillo, Howard Brookner, and Spike Lee in the process.[8] During the late 1970s in New York City, Jarmusch and his contemporaries were part of an alternative culture scene centered on the CBGB music club.[18]

In his final year at New York University, Jarmusch worked as an assistant to the renowned film noir director Nicholas Ray, who was at that time teaching in the department.[8] In an anecdote, Jarmusch recounted of the formative experience of showing his mentor his first script; Ray disapproved of its lack of action, to which Jarmusch responded after meditating on the critique by reworking the script to be even less eventful. On Jarmusch's return with the revised script, Ray reacted favourably to his student's dissent, citing approvingly the young student's obstinate independence.[19] Jarmusch was the only person Ray brought to work – as his personal assistant – on Lightning Over Water, a documentary about his dying years on which he was collaborating with Wim Wenders.[4] Ray died in 1979 after a long fight with cancer.[8] A few days afterwards, having been encouraged by Ray and New York underground filmmaker Amos Poe and using scholarship funds given by the Louis B. Mayer Foundation to pay for his school tuition,[9][20] Jarmusch started work on a film for his final project.[3][8] The university, unimpressed with Jarmusch's use of his funding as well as the project itself, promptly refused to award him a degree.[15]

Career

First features and rise to fame: Permanent Vacation and Stranger Than Paradise

Jarmusch's final year university project was completed in 1980 as Permanent Vacation, his first feature film. It had its premiere at the International Filmfestival Mannheim-Heidelberg (formerly known as Filmweek Mannheim) and won the Josef von Sternberg Award.[15] It was made on a shoestring budget of around $12,000 in misdirected scholarship funds and shot by cinematographer Tom DiCillo on 16 mm film.[21] The 75 minute quasi-autobiographical feature follows an adolescent drifter (Chris Parker) as he wanders around downtown Manhattan.[22][23] The film was not released theatrically, and did not attract the sort of adulation from critics that greeted his later work. The Washington Post staff writer Hal Hinson would disparagingly comment in an aside during a review of Jarmusch's Mystery Train (1989) that in the director's debut, "the only talent he demonstrated was for collecting egregiously untalented actors".[24] The bleak and unrefined Permanent Vacation is nevertheless one of the director's most personal films, and established many of the hallmarks he would exhibit in his later work, including derelict urban settings, chance encounters, and a wry sensibility.[23][25]

Jarmusch's first major film, Stranger Than Paradise, was produced on a budget of approximately $125,000 and released in 1984 to much critical acclaim.[26][27] A deadpan comedy recounting a strange journey of three disillusioned youths from New York through Cleveland to Florida, the film broke many conventions of traditional Hollywood filmmaking.[28] It was awarded the Camera d'Or at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival as well as the 1985 National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Film,[29][30] and became a landmark work in modern independent film.[31]

Down by Law, Mystery Train, and Night on Earth

In 1986, Jarmusch wrote and directed Down by Law, starring musicians John Lurie and Tom Waits, and Italian comic actor Roberto Benigni (his introduction to American audiences) as three convicts who escape from a New Orleans jailhouse.[32] Shot like the director's previous efforts in black and white, this constructivist neo-noir was Jarmusch's first collaboration with renowned Dutch cinematographer Robby Müller, who had been known for his work with Wenders.[33]

His next two films each experimented with parallel narratives: Mystery Train (1989) told three successive stories set on the same night in and around a small Memphis hotel, and Night on Earth (1991)[34] involved five cab drivers and their passengers on rides in five different world cities, beginning at sundown in Los Angeles and ending at sunrise in Helsinki.[19] Less bleak and somber than Jarmusch's earlier work, Mystery Train nevertheless retained the director's askance conception of America.[35] He wrote Night on Earth in about a week, out of frustration at the collapse of the production of another film he had written and the desire to visit and collaborate with friends such as Benigni, Gena Rowlands, Winona Ryder and Isaach de Bankolé.[36]

As a result of his early work, Jarmusch became an influential representative of the trend of the American road movie.[37] Not intended to appeal to mainstream filmgoers, these early Jarmusch films were embraced by art house audiences,[38] gaining a small but dedicated American following and cult status in Europe and Japan.[39] Each of the four films had its premiere at the eminent and discerning New York Film Festival, while Mystery Train was in competition at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival.[29] Jarmusch's distinctive aesthetic and auteur status fomented a critical backlash at the close of this early period, however; though reviewers praised the charm and adroitness of Mystery Train and Night On Earth, the director was increasingly charged with repetitiveness and risk-aversion.[15][29]

A film appearance in 1989 as a used car dealer in the cult comedy Leningrad Cowboys Go America further solidified his interest and participation in the road movie genre. In 1991 Jim Jarmusch appeared as himself in Episode One of John Lurie's cult television series Fishing With John.

1995–99: Dead Man and Ghost Dog

In 1995, Jarmusch released Dead Man, a period film set in the 19th century American West starring Johnny Depp and Gary Farmer. Produced at a cost of almost $9 million with a high-profile cast including John Hurt, Gabriel Byrne and, in his final role, Robert Mitchum,[40] the film marked a significant departure for the director from his previous features.[41] Earnest in tone in comparison to its self-consciously hip and ironic predecessors, Dead Man was thematically expansive and of an often violent and progressively more surreal character.[15][41] The film was shot in black and white by Robby Müller, and features a score composed and performed by Neil Young, for whom Jarmusch subsequently filmed the tour documentary Year of the Horse, released to tepid reviews in 1997.

Though ill-received by mainstream American reviewers, Dead Man found much favor internationally and among critics, many of whom lauded it as a visionary masterpiece.[15] It has been hailed as one of the few films made by a Caucasian that presents an authentic Native American culture and character, and Jarmusch stands by it as such, though it has attracted both praise and castigation for its portrayal of the American West, violence, and especially Native Americans.[42]

Following artistic success and critical acclaim in the American independent film community, he achieved mainstream renown with his far-East philosophical crime film Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, shot in Jersey City and starring Forest Whitaker as a young inner-city man who has found purpose for his life by unyieldingly conforming it to the Hagakure, an 18th-century philosophy text and training manual for samurai, becoming, as directed, a terrifyingly deadly hit-man for a local mob boss to whom he may owe a debt, and who then betrays him. The soundtrack was supplied by RZA of the Wu-Tang Clan, which blends into the director's "aesthetics of sampling".[43] The film was unique among other things for the number of books important to and discussed by its characters, most of them listed bibliographically as part of the end credits. The film is also considered to be a homage to Le Samourai, a 1967 French New Wave film by auteur Jean-Pierre Melville, which starred renowned French actor Alain Delon in a strikingly similar role and narrative.

2004–09: Coffee and Cigarettes, Broken Flowers and The Limits of Control

A five-year gap followed the release of Ghost Dog, which the director has attributed to a creative crisis he experienced in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks in New York City.[11] 2004 saw the eventual release of Coffee and Cigarettes, a collection of eleven short films of characters sitting around drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes that had been filmed by Jarmusch over the course of the previous two decades. The first vignette, "Strange to Meet You", had been shot for and aired on Saturday Night Live in 1986, and paired Roberto Benigni with comedian Steven Wright. This had been followed three years later by "Twins", a segment featuring actors Steve Buscemi and Joie and Cinqué Lee, and then in 1993 with the Short Film Palme d'Or-winning "Somewhere in California", starring musicians Tom Waits and Iggy Pop.[44]

He followed Coffee and Cigarettes in 2005 with Broken Flowers, which starred Bill Murray as an early retiree who goes in search of the mother of his unknown son in attempt to overcome a midlife crisis. Following the release of Broken Flowers, Jarmusch signed a deal with Fortissimo Films, whereby the distributor would fund and have "first-look" rights to the director's future films, and cover some of the overhead costs of his production company, Exoskeleton.[45]

In 2009, Jarmusch released, The Limits of Control, a sparse, meditative crime film set in Spain, it starred Isaach de Bankolé as a lone assassin with a secretive mission.[46] A behind-the-scenes documentary, Behind Jim Jarmusch, was filmed over three days on the set of the film in Seville by director Léa Rinaldi.[47]

In October 2009, Jarmusch appeared as himself in an episode of the HBO series Bored to Death, and the following September, Jarmusch helped to curate the All Tomorrow's Parties music festival in Monticello, New York.

2010–14: Only Lovers Left Alive

In an August 2010 interview, Jarmusch revealed his forthcoming work schedule at that time:

I'm working on a documentary about the Stooges [Iggy Pop-fronted band]. It's going to take a few years. There's no rush on it, but it's something that Iggy asked me to do. I'm co-writing an "opera." It won't be a traditional opera, but it'll be about the inventor Nikola Tesla, with the composer Phil Klein. I have a new film project that's really foremost for me that I hope to shoot early next year with Tilda Swinton and Michael Fassbender and Mia Wasikowska, who was Alice in Wonderland in Tim Burton's film. I don't have that quite financed yet, so I'm working on that. I'm also making music and hoping to maybe score some silent films to put out. Our band will have an EP that we'll give out at ATP. We have enough music for three EPs or an album.[48]

Jarmusch eventually attained funding for the aforementioned film project after a protracted period and, in July 2012, Jarmusch began shooting Only Lovers Left Alive with Tilda Swinton, Tom Hiddleston (who replaced Fassbender), Mia Wasikowska, Anton Yelchin, and John Hurt,[49] while Jarmusch's musical project SQÜRL were the main contributors to the film's soundtrack.[50] The film screened at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival and the 2013 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF),[51] with Jarmusch explaining the seven-year completion time frame at the former: "The reason it took so long is that no one wanted to give us the money. It took years to put it together. Its getting more and more difficult for films that are a little unusual, or not predictable, or don't satisfy people's expectations of something."[52] The film's budget was US$7 million and its UK release date was February 21, 2014.[53]

As a filmmaker

In 2014 Jarmusch shunned the "auteur theory" and likened the filmmaking process to human sexual reproduction:

I put 'A film by' as a protection of my rights, but I don't really believe it. It's important for me to have a final cut, and I do for every film. So I'm in the editing room every day, I'm the navigator of the ship, but I'm not the captain, I can't do it without everyone's equally valuable input. For me it's phases where I'm very solitary, writing, and then I'm preparing, getting the money, and then I'm with the crew and on a ship and it's amazing and exhausting and exhilarating, and then I'm alone with the editor again … I've said it before, it's like seduction, wild sex, and then pregnancy in the editing room. That's how it feels for me.[50]

Style

| “ | Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination. Devour old films, new films, music, books, paintings, photographs, poems, dreams, random conversations, architecture, bridges, street signs, trees, clouds, bodies of water, light and shadows. Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable; originality is nonexistent. And don’t bother concealing your thievery – celebrate it if you feel like it. In any case, always remember what Jean-Luc Godard said: “It’s not where you take things from – it’s where you take them to.” | ” |

| — Jim Jarmusch, The Golden Rules of Filming[54] | ||

Jarmusch has been characterized as a minimalist filmmaker whose idiosyncratic films are unhurried.[26][55] His films often eschew traditional narrative structure, lacking clear plot progression and focus more on mood and character development.[11][55][56] In an interview early in his career, he stated that his goal was "to approximate real time for the audience."[57]

Jarmusch's early work is marked by a brooding, contemplative tone, featuring extended silent scenes and prolonged still shots.[41] He has experimented with a vignette format in three films that were either released, or begun around, the early 1990s: Mystery Train, Night on Earth and Coffee and Cigarettes. The Salt Lake Tribune critic Sean P. Means wrote that Jarmusch blends "film styles and genres with sharp wit and dark humor",[58] while his style is also defined by a signature deadpan comedic tone.[46]

The protagonists of Jarmusch's films are usually lone adventurers.[3] The director's male characters have been described by critic Jennie Yabroff as "three time losers, petty thiefs and inept con men, all [...] eminently likeable, if not down right charming";[41] while novelist Paul Auster described them as "laconic, withdrawn, sorrowful mumblers".[17]

Jarmusch has revealed that his instinct is a greater influence during the filmmaking process than any cognitive processes. He explained: "I feel like I have to listen to the film and let it tell me what it wants. Sometimes it mumbles and it isn't very clear." Films such as Dead Man and Limits of Control have polarized fans and general viewers alike, as Jarmusch's stylistic instinct is embedded in his strong sense of independence.[59]

Themes

Though his films are predominantly set in the United States, Jarmusch has advanced the notion that he looks at America "through a foreigner's eyes", with the intention of creating a form of world cinema that synthesizes European and Japanese film with that of Hollywood.[9] His films have often included foreign actors and characters, and (at times substantial) non-English dialogue. In his two later-nineties films, he dwelt on different cultures' experiences of violence, and on textual appropriations between cultures: a wandering Native American's love of William Blake, a black hit-man's passionate devotion to the Hagakure. The interaction and syntheses between different cultures, the arbitrariness of national identity, and irreverence towards ethnocentric, patriotic or nationalistic sentiment are recurring themes in Jarmusch's work.[41][60]

Jarmusch's fascination for music is another characteristic that is readily apparent in his work.[15][35] Musicians appear frequently in key roles – John Lurie, Tom Waits, Gary Farmer, Youki Kudoh, RZA and Iggy Pop have featured in multiple Jarmusch films, while Joe Strummer and Screamin' Jay Hawkins appear in Mystery Train and GZA, Jack and Meg White feature in Coffee and Cigarettes. Hawkins' song "I Put a Spell on You" was central to the plot of Stranger than Paradise, while Mystery Train is inspired by and named after a song popularized by Elvis Presley, who is also the subject of a vignette in Coffee and Cigarettes.[15] In the words of critic Vincent Canby, "Jarmusch's movies have the tempo and rhythm of blues and jazz, even in their use – or omission – of language. His films work on the senses much the way that some music does, unheard until it's too late to get it out of one's head."[35]

On his narrative focus, Jarmusch remarked in a 1989 interview, "I'd rather make a movie about a guy walking his dog than about the emperor of China."[61]

Impact and legacy

Jarmusch is ascribed as having instigated the American independent film movement with Stranger Than Paradise.[32] In her description of the film in a 2005 profile of the director for The New York Times, critic Lynn Hirschberg declared that Stranger than Paradise "permanently upended the idea of independent film as an intrinsically inaccessible avant-garde form".[6] The success of the film accorded the director a certain iconic status within arthouse cinema, as an idiosyncratic and uncompromising auteur, exuding the aura of urban cool embodied by downtown Manhattan.[62][63] Such perceptions were compounded with the release of his subsequent features in the late 1980s, establishing him as one of the generation's most prominent and influential independent filmmakers.[64][65]

New York critic and festival director Kent Jones undermined the "urban cool" association that Jarmusch has garnered and was quoted in a February 2014 media article, following the release of his eleventh feature film:

There's been an overemphasis on the hipness factor – and a lack of emphasis on his incredible attachment to the idea of celebrating poetry and culture. You can complain about the preciousness of a lot of his movies, [but] they are unapologetically standing up for poetry. [His attitude is] 'if you want to call me an elitist, go ahead, I don't care'.[59]

Jarmusch's staunch independence has been represented by his success in retaining the negatives for all of his films, an achievement that was described by the Guardian's Jonathan Romney as "extremely rare." British veteran producer Jeremy Thomas, who was one of the eventual financiers of Only Lovers Left Alive called Jarmusch "one of the great American independent film-makers" who is "the last of the line." Thomas believes that filmmakers like Jarmusch "are not coming through ... any more."[59]

In a 1989 review of his work, Vincent Canby of The New York Times called Jarmusch "the most adventurous and arresting film maker to surface in the American cinema in this decade".[35] Jarmusch was recognized with the Filmmaker on the Edge award at the 2004 Provincetown International Film Festival.[66] A retrospective of the director's films was hosted at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, during February 1994, and another, "The Sad and Beautiful World of Jim Jarmusch", by the American Film Institute in August 2005.[67][68]

While Swinton, who has worked with Jarmusch on numerous occasions, describes him as a "rock star," the director admits that "I don't know where I fit in. I don't feel tied to my time." Dutch lute player Jozef van Wissem, who worked on the score for Only Lovers Left Alive calls Jarmusch a "cultural sponge" who "absorbs everything."[59]

Music

In the early 1980s, Jarmusch was part of a revolving lineup of musicians in Robin Crutchfield's Dark Day project,[69] and later became the keyboardist and one of two vocalists for The Del-Byzanteens,[8] a No Wave band whose sole LP Lies to Live By was a minor underground hit in the United States and Britain in 1982. Jarmusch is also featured on the album Wu-Tang Meets the Indie Culture (2005) in two interludes described by Sean Fennessy in a Pitchfork review of the album as both "bizarrely pretentious" and "reason alone to give it a listen".[70] Jarmusch and Michel Gondry each contributed a remix to a limited edition release of the track "Blue Orchid" by The White Stripes in 2005.[71]

The author of a series of essays on influential bands, Jarmusch has also had at least two poems published. He is a founding member of The Sons of Lee Marvin, a humorous "semi-secret society" of artists resembling the iconic actor, which issues communiqués and meets on occasion for the ostensible purpose of watching Marvin's films.[6][72]

He released two collaborative albums with lutist Jozef van Wissem, Concerning the Entrance into Eternity (Important Records) and The Mystery of Heaven (Sacred Bones Records), in 2012.[73][74]

Jarmusch is a member of rock band SQÜRL with film associate Carter Logan and sound engineer Shane Stoneback.[75][76][77][78] SQÜRL's version of Wanda Jackson’s 1961 song “Funnel of Love”, featuring Madeline Follin of Cults on vocals, opens Jarmusch's 2014 film Only Lovers Left Alive.[79]

Dutch lute composer Jozef van Wissem also collaborated with Jarmusch on the soundtrack for Only Lovers Left Alive and the pair also play in a duo. Jarmusch first met van Wissem on a street in New York City's SoHo area in 2007, at which time the lute player handed the director a CD—several months later, Jarmusch asked van Wissem to send his catalog of recordings and the two started playing together as part of their developing friendship. Van Wissem explained in early April 2014: “I know the way [Jarmusch] makes his films is kind of like a musician. He has music in his head when he’s writing a script so it’s more informed by a tonal thing than it is by anything else.”[79]

Awards

In 1980 he won with his film Permanent Vacation the Josef von Sternberg Award at the International Filmfestival Mannheim-Heidelberg. 1999 he was laureate of the Douglas Sirk Preis at Filmfest Hamburg, Germany.

In 1984 he won the Caméra d'Or at Cannes Film Festival for Stranger Than Paradise.

In 2004 Jarmusch was honored with the Filmmaker on the Edge Award at the Provincetown International Film Festival.

In 2005 he won the Grand Prix of the 2005 Cannes Film Festival for his film Broken Flowers.

Personal life

.jpg)

Jarmusch rarely discusses his personal life in public.[7][11] He divides his time between New York City and the Catskill Mountains.[7][80] He stopped drinking coffee in 1986, the year of the first installment of Coffee and Cigarettes, though he continues to smoke cigarettes.[81]

In a February 2014 interview, Jarmusch stated that he is not interested in eternal life, as "there's something about the cycle of life that's very important, and to have that removed would be a burden".[50]

Archive

The moving image collection of Jim Jarmusch is held at the Academy Film Archive.[82]

Selected filmography

- Permanent Vacation (1980)

- Stranger Than Paradise (1984)

- Down by Law (1986)

- Mystery Train (1989)

- Night on Earth (1991)

- Dead Man (1995)

- Year of the Horse (1997)

- Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999)

- Coffee and Cigarettes (2004)

- Broken Flowers (2005)

- The Limits of Control (2009)

- Only Lovers Left Alive (2013)[49]

- Paterson (2016)

- Gimme Danger (2016)

Discography

- Studio albums

- Concerning the Entrance into Eternity (Important Records, 2012) (with Jozef van Wissem)

- The Mystery of Heaven (Sacred Bones Records, 2012) (with Jozef van Wissem)

- Soundtracks

- Only Lovers Left Alive (ATP Recordings, 2013) (as Sqürl, with Jozef van Wissem)

- EPs

- EP #1 (ATP Recordings, 2013) (as Sqürl)

- EP #2 (ATP Recordings, 2013) (as Sqürl)

- EP #3 (ATP Recordings, 2014) (as Sqürl)[83]

Live albums

- SQÜRL Live at Third Man Records (12" vinyl, A Third Man Records, 2016) (as Sqürl)

- Guest appearances

- Jozef van Wissem – "Concerning the Beautiful Human Form After Death" from The Joy That Never Ends (2011)

- Fucked Up – "Year of the Tiger" (2012)

- Remixes

- The White Stripes – "Blue Orchid" (First Nations Remix) (2005)

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Birth record

- ↑ Hagen, Ray. "Wolfner Library: You Say It How?". Missouri Secretary of State web site. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Lim, Dennis (April 23, 2009). "A Director Content to Wander On". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Suárez 2007, pp. 6–11

- ↑ "Films Selected for the National Film Registry in 2002 by the Library of Congress". Library of Congress. January 2003. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Hirschberg, Lynn (July 31, 2005). "The Last of the Indies". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Hertzberg, Ludvig (October 28, 2008). "The Private Life of James R. Jarmusch". Limited Control. Posterous.com. Retrieved November 2, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Hertzberg 2001, pp. xi – xii

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hertzberg, Ludvig. "Biography from Current Biography Yearbook 1990 (abridged)". The Jim Jarmusch Resource Page. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ↑ Jarmusch, Ann (May 12, 1996). "The Jarmusch clan". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

We grew up near, not in, Akron, Ohio, in an idyllic area that seemed eons away from the stinky, grimy "Rubber Capital of the World." And our father worked for B.F. Goodrich, not Goodyear.

- 1 2 3 4 Hattenstone, Simon (November 13, 2004). "Interview: Simon Hattenstone meets Jim Jarmusch". The Guardian. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- 1 2 Jarrell, Joe (May 9, 2004). "Jim Jarmusch". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- 1 2 3 McKenna, Kristine (May 5, 1996). "Dead Man Talking". Los Angeles Times.

- 1 2 3 Schoemer, Karen (April 30, 1992). "On The Lower East Side With: Jim Jarmusch; Film as Life, and Vice Versa". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Crow, Jonathan. "Jim Jarmusch > Biography". allmovie. All Media Guide. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Langdon, Matt (March 17, 2000). "The Way of the Indie God". iFMagazine. Archived from the original on February 10, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- 1 2 Auster, Paul (September 7, 2007). "Night on Earth: New York – Jim Jarmusch, Poet". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ↑ Olsen, Mark (April 26, 2009). "Jim Jarmusch on 'The Limits of Control'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- 1 2 Kennedy, Mark (March 19, 2000). "Jim Jarmusch refuses to go along". The Columbian. Associated Press.

He's never seen Obi-Wan Kenobi spar with Darth Vader, or Rhett Butler pop off to Scarlett.

Jim Jarmusch, the art-house filmmaker who helped spark a renaissance in independent film, refuses to actually sit through some of the classics of American cinema.

"I pledge I will go to my grave having never seen Gone with the Wind or any Star Wars film," Jarmusch says. "Just to be obstinate. No other good reason."

It's a typical stance from a moviemaker who stubbornly creates films that critics often complain are too long, too meandering, and too often in black and white. - ↑ Suárez 2007, p. 21

- ↑ "Jim Jarmusch". The Guardian. November 15, 1999. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ↑ Levy, Shawn (April 2000). "Postcards from Mars". Sight & Sound. 10 (4): 22–24. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- 1 2 Canby, Vincent (September 20, 1990). "Jim Jarmusch's First Feature at Archives". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ↑ Hinson, Hal (February 2, 1990). "Mystery Train (R)". The Washington Post. The Washington Post Company. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ↑ Jenkins, Mark (August 31, 2007). "Rediscovering Jarmusch's Minimalist Paradise". Washington Post. Washington Post Company. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- 1 2 Burr, Ty (March 10, 2000). "Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 17, 2009.

... minimalist director who found fame with 1984's Stranger Than Paradise ...

- ↑ Sterritt, David (February 21, 1985). "On the fringes of film: writer-director Jim Jarmusch". Christian Science Monitor.

Jim Jarmusch brought in "Stranger Than Paradise" for about $125,000. That's not a budget in today's movie world; it's lunch money.

- ↑ Tobias, Scott (May 19, 2004). "Jim Jarmusch". The A.V. Club. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Tasker, Yvonne (2002). "Stranger than Fiction: The rise and fall of Jim Jarmusch". Fifty Contemporary Filmmakers. Routledge Key Guides. New York: Routledge. pp. 177–178. ISBN 0-415-18974-8. OCLC 47764371.

- ↑ Hartl, John (March 16, 2000). "New on videotape". The Seattle Times. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- ↑ "Stranger Than Paradise (1984)". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- 1 2 Host: Bob Edwards (March 10, 2000). "Profile: Jim Jarmusch's new film, Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai". Morning Edition. National Public Radio.

The 1984 movie Stranger Than Paradise by Jim Jarmusch is credited with launching the independent film movement. Two years later, Jarmusch introduced American audiences to the wacky Italian actor Roberto Benigni in Down by Law.

- ↑ Kempley, Rita (October 3, 1986). "Down by Law". The Washington Post. The Washington Post Company. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ↑ See Gabri Ródenas (2009), Guía para ver y analizar Noche en la Tierra de Jim Jarmusch, Barcelona/Valencia: Octaedro/Nau Llibres, ISBNs: 978-84-8063-931-6 /978-84-7642-776-7. Unluckily, It's not in English, just in Spanish

- 1 2 3 4 Canby, Vincent (November 12, 1989). "The Giddy Minimalism Of Jim Jarmusch". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ↑ "Jim Jarmusch – part two". The Guardian. November 15, 1999. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ↑ Mazierska, Ewa; Rascaroli, Laura (2006). Crossing New Europe. Wallflower Press. p. 3. ISBN 1-904764-67-3. OCLC 63137371.

In reverse, North American directors started to absorb the influence of European road cinema, usually mediated by the 'American' films by Wim Wenders and Werner Herzog (Stroszek, 1977). The most influential representative of this trend in recent times is Jim Jarmusch, starting with his Stranger than Paradise from 1984.

- ↑ Rosen, Steven (March 19, 2000). "Change may be in the wind: Jarmusch indie film has mainstream feel". The Denver Post.

Jim Jarmusch, one of the most fiercely independent of current American writer-directors, has never cared if his movies gain mass acceptance.

He's been content to appeal to the devoted if limited audience that responds to film as art. And that audience has embraced his Stranger Than Paradise, Down By Law, Mystery Train and Night on Earth. - ↑ Katzman, Lisa (May 3, 1992). "The Jarmusch touch in Night on Earth, America's coolest director exhudes a new warmth". Chicago Tribune.

Walking into the cafe where we've agreed to meet on a hot spring day, director Jim Jarmusch takes off his signature black leather jacket. It's the type worn by blues musicians, '50s greasers and the downbeat bohemian odd couple Willie and Eddie of Jarmusch's second film Stranger than Paradise. A small triangular silver Triumph motorcycle pin affixed to the lapel is a tip-off to one of Jarmusch's chief recreational passions. Among Jarmusch cognoscenti, the shock of thick, almost white hair that rises from his head in a handsomely shaped post-punk spike is another unmistakable signature.

In the eight years since Stranger than Paradise became an arthouse hit, Jarmusch has garnered a loyal but limited American audience. Yet abroad, particularly in Japan and Europe, both Jarmusch and his films have achieved cult status. For foreigners, perhaps even more so than for Americans, Jarmusch's films are the sine qua non of post-modern American hipdom. They articulate a distinctly funky, low-tech, outcast vision of American society that in both ethos and esthetics draws upon and amusingly blends the past five decades of postwar culture. While in content his films quietly defy Hollywood's myths of American progress and prosperity, in form (due to their stylistic simplicity and small budgets) they are a retort to the movie industry's bloated excess.

Recently, at the Yugoslavian film festival, 6,000 people turned out to fill a 4,000-seat theater for a midnight showing of Jarmusch's latest film, Night on Earth in wartorn Belgrade. In the past several months a traveling "Jim Jarmusch Film Festival" was held in major cities throughout Poland. Czechoslavakia [sic] will soon hold such a festival. And in Japan, where the director is a national celebrity, he is offered huge sums to appear in and direct commercials. To date he has turned down all offers. - ↑ Susman, Gary (May 9–16, 1996). "Dead Man talking". Boston Phoenix. Phoenix Media/Communications Group. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Yabroff, Jennie. "Jim Jarmusch, Rock and Roll Director". Addicted to Noise. 2 (6). Archived from the original on August 3, 2002. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ↑ Hall, Mary Katherine (Winter 2000). "Now You Are a Killer of White Men: Jim Jarmusch's Dead Man and Traditions of Revisionism in the Western". Journal of Film and Video. 52 (4): 3–14.

- ↑ Gonzalez, "Jim Jarmusch’s Aesthetics of Sampling in Ghost Dog–The Way of the Samurai", 2004.

- ↑ Caro, Mark (May 28, 2004). "With 'Coffee,' Jim Jarmusch lacks for rush". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

But then 1992's "Somewhere in California," which won the Cannes Film Festival's short-film Palme D'Or, offers the delicious spectacle of [Iggy Pop] and [Tom Waits] meeting in some remote dumpy bar, with Iggy playing the shaggy, eager-to-please puppy while the edgy Waits finds ways to take constant umbrage.

- ↑ Dawtrey, Adam (May 17, 2005). "Jim Jarmusch". Daily Variety. Reed Business Information.

Jim Jarmusch, whose latest pic "Broken Flowers" premieres in the Cannes competition today, has struck a multi-year first-look deal with Fortissimo Films.

This is the first time Fortissimo has entered a formal long-term relationship with an individual filmmaker, and marks a major step forward by the Hong Kong and Amsterdam-based sales company in its drive for English-language movies.

Fortissimo has agreed to provide financing to upcoming Jarmusch films, including a contribution to the overheads of his New York-based production banner Exoskeleton. - 1 2 Tobias, Scott (May 8, 2009). "Jim Jarmusch". The A.V. Club. The Onion. Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- ↑ Hertzberg, Ludwig (June 24, 2009). "Behind Jim Jarmusch". Limited Control. Posterous. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- ↑ Breihan, Tom (August 20, 2010). "Filmmaker Jim Jarmusch Talks ATP". Pitchfork.com. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- 1 2 Roxborough, Scott (January 30, 2012). "Tilda Swinton, John Hurt Join Jim Jarmusch's Vampire Film 'Only Lovers Left Alive'". The Hollywood Reporter.

- 1 2 3 David Ehrlich (20 February 2014). "Jim Jarmusch: 'Women are my leaders'". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ "2013 Official Selection". Cannes. 18 April 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ↑ Andrew Pulver (25 May 2013). "Cannes 2013: Only Lovers Left Alive a seven year trek says Jim Jarmusch". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ Oliver Franklin (23 January 2014). "Hiddleston! Swinton! Hurt! Watch the new trailer for Only Lovers Left Alive". GQ British. Condé Nast UK. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ Jarmusch, Jim (January 22, 2004). "Jim Jarmusch’s Golden Rules". MovieMaker Magazine. MovieMaker Publishing. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- 1 2 "Director Jim Jarmusch delivers offbeat mob movie Ghost Dog". The News Tribune. April 21, 2000.

Jim Jarmusch makes movies unlike anyone else's. They're unhurried. They're populated by the oddest characters. They do not proceed in straight lines. They're one of a kind.

- ↑ Travers, Peter (April 11, 2001). "Night on Earth : Review". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ↑ Robinson, Walter. "BOMB Magazine — Men Looking at Other Men by Lindzee Smith". Bombsite.com. Retrieved 2014-05-20.

- ↑ Means, Sean P. (April 21, 2000). "A Samurai Warrior Haunts New Jersey in Ghost Dog". The Salt Lake Tribune.

Jim Jarmusch has always applied the Cuisinart approach to moviemaking, blending film styles and genres with sharp wit and dark humor

- 1 2 3 4 Jonathan Romney (22 February 2014). "Jim Jarmusch: how the film world's maverick stayed true to his roots". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ↑ Klein, Joshua (March 15, 2000). "Jim Jarmusch". The A.V. Club. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ↑ Hertzberg 2001, p. 92

- ↑ Dretzk, Gary (June 30, 1996). "Poets and Indians: Jim Jarmusch goes West to bring Dead Man to life". Chicago Tribune.

An idiosyncratic filmmaker whose hip, ironic style has wowed the art-house crowd since the quirky Stranger Than Paradise was released in 1984, Jarmusch embodies urban cool and uncompromising auteurism. His pictures are at once funny, gritty, highly challenging and undeniably American in their multicultural vision.

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (March 22, 1996). "A gun up your ass: an interview with Jim Jarmusch". Cineaste. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ↑ Blair, Iain (March 2, 2000). "From writing to directing, Jarmusch is in charge". Chicago Tribune.

Over the last decade [Jim] Jarmusch has established himself as one of the leading independent filmmakers of his generation with such comedic and ironic films as "Stranger Than Paradise," "Down by Law," "Mystery Train," "Night on Earth" and "Dead Man." With his latest film, which he wrote, produced and directed, Jarmusch once again marches to the beat of his own drummer.

- ↑ Holleman, Joe (March 24, 2000). "Forest Whitaker personifies cool in Jarmusch's latest offbeat film". St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

With the possible exception of John Sayles, there is no independent director who has influenced the modern independent film world more than Jim Jarmusch.

By combining odd characters, dark comedy and an incredibly hip atmosphere in classic art-house films such as Down by Law and Stranger Than Paradise, Jarmusch has influenced and assisted younger indie directors in finding a modicum of commercial success with less-than-mainstream fare. - ↑ Kimmel, Dan (April 6, 2004). "Jarmusch will journey to Provincetown for nod". Daily Variety.

Indie filmmaker Jim Jarmusch will be the sixth recipient of the Filmmaker on the Edge award at the 2004 Provincetown Film Festival, to be held June 16–20 in Provincetown, Mass.

- ↑ "Now at AFI: The World of Jim Jarmusch". The Washington Post. August 5, 2005.

This month at its Silver Theatre (8633 Colesville Rd., Silver Spring), the American Film Institute is presenting "The Sad and Beautiful World of Jim Jarmusch," a retrospective of most of the filmmaker's works

- ↑ "Connect the dots". St. Paul Pioneer Press. February 14, 1994.

Jim Jarmusch has big hair – Lyle Lovett big. It suits the man whose too-hip-to-live reputation has made him the King of Counterculture Film and whose work is featured in a Walker Art Center retrospective this month. Jarmusch's disjointed, oddly comic movies and short films, which include Stranger Than Paradise and Night on Earth, have established him as a master of the minutely observed detail. In his little-seen debut,...

- ↑ Hertzberg, Ludvig (September 15, 2008). "Dark Day". Limited Control. Posterous.com. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- ↑ Fennessy, Sean. "Pitchfork: Various Artists: Dreddy Krueger Presents...Think Differently Music: Wu-Tang Meets the Indie Culture". Pitchfork. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ↑ Hertzberg, Ludvig (September 17, 2008). "Connecting the white stripes". Limited Control. Posterous.com. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- ↑ Hertzberg 2001, p. 187

- ↑ Masters, Marc (February 22, 2012). "Jim Jarmusch: Concerning the Entrance Into Eternity". Pitchfork.

- ↑ Kivel, Adam (November 15, 2012). "Album Review: Jozef Van Wissem & Jim Jarmusch – The Mystery of Heaven". Consequence of Sound.

- ↑ Agarwal, Manish. "Molten Meditations: Jim Jarmusch & SQÜRL Interviewed", thequietus.com, November 19th, 2013. Retrieved on January 28, 2014

- ↑ McGovern, Kyle. "Stream 'Pink Dust,' From Jim Jarmusch's Renamed Weirdo Noise Project SQURL", spin.com, April 19, 2013. Retrieved on January 28, 2014

- ↑ Neyland, Nick. Pitchfork Review, pitchfork.com, May 20, 2013. Retrieved on January 28, 2014

- ↑ Cole, Alec. "Jim Jarmusch’s SQURL Announces New Release EP #2 For November 2013 Release", mxdwn.com, October 20, 2013. Retrieved on January 28, 2014

- 1 2 Steve Dollar (11 April 2014). "Jozef van Wissem wants to make the lute ‘sexy again,’ and Jim Jarmusch is helping him". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ↑ Jarmusch, Jim (August 16, 2005). "Fresh Air". National Public Radio (Interview: audio). Interview with Terry Gross. WHYY. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- ↑ Torday, Daniel (June 1, 2005). "Q&A with Jim Jarmusch". Esquire. Retrieved May 19, 2009.

- ↑ "Jim Jarmusch". Academy Film Archive.

- ↑ Sqürl discography at Discogs

References

- Hertzberg, Ludvig (2001). Jim Jarmusch: Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-379-5. OCLC 46319700.

- Gonzalez, Éric, "Jim Jarmusch’s Aesthetics of Sampling in Ghost Dog–The Way of the Samurai", Volume!, vol. 3, n° 2, Nantes: Éditions Mélanie Seteun, 2004, pp. 109–121.

- Suárez, Juan Antonio (2007). Jim Jarmusch. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-07443-2. OCLC 71275566.

- Ródenas, Gabri (2009), Guía para ver y analizar Noche en la Tierra de Jim Jarmusch, Barcelona / Valencia: Octaedro / Nau Llibres. ISBN 978-84-8063-931-6 / 978-84-7642-776-7

- Ródenas, Gabri (2009), “Jarmusch y Carver: Se ha roto el frigorífico” in Fernández, P. (Ed.), Rompiendo moldes: Discursos, género e hibridación en el siglo XXI. Zamora/Sevilla: Editorial Comunicación Social. ISBN 978-84-96082-88-5. Available at Google Books.

- Ródenas, Gabri (2009), “Jarmusch Vs Reagan” in Revista Odisea. Almería: University of Almería. December 2009. ISSN 1578-3820.

- Ródenas, Gabri (2010), “Jim Jarmusch: Del insomnio americano al insomnio universal”, in Comunicación y sociedad, Navarra: University of Navarra, June 2010. ISSN 0214-0039.

- Ródenas, Gabri (2011), Jim Jarmusch: Lecturas sobre el insomnio americano (1980–1991), Spain/Germany: – Editorial Académica Española – LAP Lambert Academic Publishing GmbH & Co. KG. ISBN 978-3-8443-3503-3.

- Mentana, Umberto (2016), Il cinema di Jim Jarmusch. Una filmografia per un'analisi della cultura e del cinema postmoderno, Aracne Editrice, ISBN 978-88-548-9115-9

Further reading

- Aurich, Rolf; Reinecke, Stefan (2001). Jim Jarmusch. Bertz + Fischer. ISBN 3-929470-80-2. OCLC 53289688.

- Morse, Erik (May 6, 2009). "The man in Control: Jim Jarmusch interview". San Francisco Bay Guardian.

- Rice, Julian. (2012). The Jarmusch Way: Spirituality and Imagination in Dead Man, Ghost Dog, and The Limits of Control. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8572-1 (hardcover). ISBN 978-0-8108-8573-8 (ebook).

- Smith, Gavin (May–June 2009). "Altered States: Jim Jarmusch interview". Film Comment.

External links

- Jim Jarmusch on IMDb

- Jim Jarmusch at AllMovie

- Jim Jarmusch discography at Discogs

- Jim Jarmusch at the Senses of Cinema Great Directors critical database

- The Jim Jarmusch Resource Page, curated by Jarmusch scholar Ludvig Hertzberg

- Limited Control, Hertzberg's companion blog

- It's a sad and beautiful world

- The films of Jim Jarmusch, Hell Is For Hyphenates, May 31, 2014