Persecution of Jews and Muslims by Manuel I of Portugal

On 5 December 1496, King Manuel I of Portugal signed the decree of expulsion of Jews and Muslims to take effect by the end of October of the next year.[1]

Background

Until the 15th century, some Jews occupied prominent places in Portuguese political and economic life. For example, Isaac Abrabanel was the treasurer of King Afonso V of Portugal. Many also had an active role in Portuguese culture, and they kept their reputation of diplomats and merchants. By this time, Lisbon and Évora were home to important Jewish communities.

Expulsion of Jews

.png)

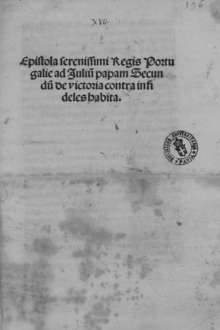

On 5 December 1496, because a clause of the contract of marriage between himself and Isabella, Princess of Asturias stipulated he do so in order to win her hand, King Manuel I of Portugal decreed that all Jews must convert to Catholicism or leave the country. One set of laws demonstrated the King's wish to completely and forever eradicate Judaism from Portugal.[1] The initial edict of expulsion was turned into an edict of forced conversion in 1497: Portuguese Jews were prevented from leaving the country and forcibly converted to Christianity. Hard times followed for the Portuguese conversos, with the massacre of 2000 individuals in Lisbon in 1506 and the later and even more relevant establishment of the Portuguese Inquisition in 1536.[2] The Portuguese inquisition was extinguished in 1821 by the "General Extraordinary and Constituent Courts of the Portuguese Nation".

When the King allowed conversos to leave after the Lisbon massacre of 1506, many went to the Ottoman Empire (notably Thessaloniki and Constantinople and to Morocco. Smaller numbers went to Amsterdam, France, Brazil, Curaçao and the Antilles. In some of these places their presence can still be witnessed, like the use of the Ladino language by some Jewish communities in Turkey, the Portuguese based dialects of the Antilles, or the multiple synagogues built by those who became known as the Spanish and Portuguese Jews, such as the Amsterdam Esnoga. They were called Maranos.

Jews who converted to Christianity were known as New Christians, and were always under the constant surveillance of the Inquisition. Many of those were crypto-Jews who continued to secretly practice their religion; they eventually left the country in the centuries to come and again embraced openly their Jewish faith. Such was the case, for example, of the family of Baruch Spinoza.

Some of the most famous descendants of Portuguese Jews who lived outside Portugal are the philosopher Baruch Spinoza (from Portuguese Bento de Espinosa), and the classical economist David Ricardo.

Crypto-Jews

Some Jews, very few, like the Belmonte Jews, went for a different and radical solution, practicing their faith in a strict secret isolated community. Known as the Marranos, some have survived until today (basically only the community from Belmonte, plus some more isolated families) by the practice of inmarriage and few cultural contacts with the outside world. Only recently have they re-established contact with the international Jewish community and openly practice religion in a public synagogue with a formal Rabbi.

Expulsion of Muslims

According to contemporary historian François Soyer, the expulsion of Muslims from Portugal has been overshadowed by the forced conversion of Jews in the country.[3] While tolerance of Muslim minorities in Portugal was higher than in any other part of Europe,[4] Muslims were still perceived as "alien."[5] Anti-Muslim riots were regular in neighboring Valencia during the 1460's; however, no similar acts of violence occurred in Portugal.[4]

In December 1496, Manual I ordered all Muslim subjects to leave without any apparent provocation.[6] According to 15th-century Portuguese historians Damião de Góis and Jerónimo Osório, the Portuguese government originally planned to forcibly convert or execute Muslims as they had done to Jews, but fear of retaliation from Muslim kingdoms in North Africa led the king to settle on deportations instead.[7] Manuel I's motivation behind the order is unclear, but some contemporary historians say it was part of a greater goal of Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand (known as the "Catholic Monarchs") to rid the peninsula of Muslims and create "religious uniformity" and "monolithic Catholic Christian unity".[8] Other historians say it was influenced by ambitions of conquering Morocco,[9] or by the suggestion of the Dominican confessor to the king, Friar Jorge Vogado.[10] Some Muslims found refuge in Castile,[11] but most fled to North Africa.[12]

Return of some Jews to Portugal

In the 19th century, some affluent families of Sephardi Jewish Portuguese origin such as the Ruah and Bensaude, resettled in Portugal from Morocco. The first synagogue to be built in Portugal since the 15th century was the Lisbon Synagogue, inaugurated in 1904.

In 2014 the Portuguese parliament changed the Portuguese nationality law in order to grant Portuguese nationality to descendants of Sephardi Jews expelled from Portugal. The law is a reaction to historical events that led to their expulsion from Portugal, but also due to increased concerns over Jewish communities throughout Europe. In order to obtain Portuguese nationality, the person must have a family surname that attests being a direct descendant of a Sephardi of Portuguese origin, or with family connections in a collateral line from a former Portuguese Sephardi community. Use of expressions in Portuguese in Jewish rites or Judaeo-Portuguese or Ladino can also be considered proof.[13]

From 2015 several hundred Turkish Jews who were able to prove descent from Portuguese Jews expelled in 1497 emigrated to Portugal and acquired Portuguese citizenship.[14][15][16]

See also

References

- 1 2 António José Saraiva: The Marrano Factory: The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians 1536-1765, BRILL, 2001, ISBN 9789004120808, p. 10-12.

- ↑ "Sao Tome & Principle". Jewish Virtual Library.

- ↑ Soyer 2007, p. 241.

- 1 2 Soyer 2007, p. 258.

- ↑ Soyer 2007, p. 254, 259.

- ↑ Soyer 2007, p. 242.

- ↑ Soyer 2007, pp. 260-261.

- ↑ Soyer 2007, p. 269.

- ↑ Soyer 2007, p. 280.

- ↑ Soyer 2007, p. 273.

- ↑ Soyer 2007, p. 262.

- ↑ Soyer 2007, p. 268.

- ↑ Lusa. "Descendentes de judeus sefarditas já vão poder pedir a nacionalidade". PÚBLICO.

- ↑ http://www.timesofisrael.com/amid-rising-european-anti-semitism-portugal-sees-jewish-renaissance/

- ↑ http://www.timesofisrael.com/new-citizenship-law-has-jews-flocking-to-tiny-portugal-city/

- ↑ http://www.jta.org/2015/03/03/news-opinion/world/portugal-open-to-citizenship-applications-by-descendants-of-sephardic-jews

Source

Soyer, François (2007). The Persecution of the Jews and Muslims of Portugal: King Manuel I and the End of Religious Tolerance (1496–7). Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 9789004162624. Retrieved 15 May 2017.