Jewish mysticism

| Jewish mysticism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Forms

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

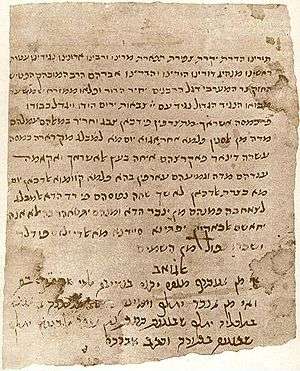

Academic study of Jewish mysticism, especially since Gershom Scholem's Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (1941), distinguishes between different forms of mysticism across different eras of Jewish history. Of these, Kabbalah, which emerged in 12th-century Europe, is the most well known, but not the only typologic form, or the earliest to emerge. Among previous forms were Merkabah mysticism (c. 100 BCE – 1000 CE), and Chassidei Ashkenaz (early 13th century CE) around the time of Kabbalistic emergence.

Kabbalah means "received tradition", a term previously used in other Judaic contexts, but which the Medieval Kabbalists adopted for their own doctrine to express the belief that they were not innovating, but merely revealing the ancient hidden esoteric tradition of the Torah. This issue is crystallised until today by alternative views on the origin of the Zohar, the main text of Kabbalah. Traditional Kabbalists regard it as originating in Tannaic times, redacting the Oral Torah, so do not make a sharp distinction between Kabbalah and early Rabbinic Jewish mysticism. Academic scholars regard it as a synthesis from Medieval times, but assimilating and incorporating into itself earlier forms of Jewish mystical tradition, as well as other philosophical elements.

The theosophical aspect of Kabbalah itself developed through two historical forms: "Medieval/Classic/Zoharic Kabbalah" (c.1175 – 1492 – 1570), and Lurianic Kabbalah (1569 CE – today) which assimilated Medieval Kabbalah into its wider system and became the basis for modern Jewish Kabbalah. After Luria, two new mystical forms popularised Kabbalah in Judaism: antinomian-heretical Sabbatean movements (1666 – 18th century CE), and Hasidic Judaism (1734 CE – today). In contemporary Judaism, the only main forms of Jewish mysticism followed are esoteric Lurianic Kabbalah and its later commentaries, the variety of schools in Hasidic Judaism, and Neo-Hasidism (incorporating Neo-Kabbalah) in non-Orthodox Jewish denominations.

Two non-Jewish syncretic traditions also popularised Judaic Kabbalah through its incorporation as part of general Western esoteric culture from the Renaissance onwards: theological Christian Cabala (c. 15th – 18th century) which adapted Judaic Kabbalistic doctrine to Christian belief, and its diverging occultist offshoot Hermetic Qabalah (c. 15th century – today) which became a main element in esoteric and magical societies and teachings. As separate traditions of development outside Judaism, drawing from, syncretically adapting, and different in nature and aims from Judaic mysticism, they are not listed on this page.

Three aims in Jewish mysticism

The Kabbalistic form of Jewish mysticism itself divides into three general streams: the Theosophical/Speculative Kabbalah (seeking to understand and describe the divine realm), the Meditative/Ecstatic Kabbalah (seeking to achieve a mystical union with God), and the Practical/Magical Kabbalah (seeking to theurgically alter the divine realms and the World). These three different, but inter-relating, methods or aims of mystical involvement are also found throughout the other pre-Kabbalistic and post-Kabbalistic stages in Jewish mystical development, as three general typologies. As in Kabbalah, the same text can contain aspects of all three approaches, though the three streams often distill into three separate literatures under the influence of particular exponents or eras.

Within Kabbalah, the theosophical tradition is distinguished from many forms of mysticism in other religions by its doctrinal form as a mystical "philosophy" of Gnosis esoteric knowledge. Instead, the tradition of Meditative Kabbalah has similarity of aim, if not form, with usual traditions of general mysticism; to unite the individual intuitively with God. The tradition of theurgic Practical Kabbalah in Judaism, censored and restricted by mainstream Jewish Kabbalists, has similarities with non-Jewish Hermetic Qabalah magical Western Esotericism. However, as understood by Jewish Kabbalists, it is censored and forgotten in contemporary times because without the requisite purity and holy motive, it would degenerate into impure and forbidden magic. Consequently, it has formed a minor tradition in Jewish mystical history.

Historical forms of Jewish mysticism timeline

| Historical phase[1] | Dates | Influential developments and texts |

|---|---|---|

| Prophetic Judaism[2] | 800–6th century BCE | Prophetic meditation, divine encounter, mystical elements: Isaiah Ezekiel Zechariah |

| Apocalyptic Judaism | Beginning 6th century BCE 300–100 BCE | Mystical and apocalyptic speculation, heavenly angelology and eschatology: 1 Enoch Daniel |

| Mystical elements in Second Temple period sects | c. 200 BCE-c. 100 CE | Mystical and pious elements among sects in the late Second Temple period in Judea and the Diaspora: Hasideans Essenes Philo's Platonic philosophy influence on early Christianity Christian Jewish early Christian mysticism |

| Early Rabbinic mysticism and mystical elements in classic Rabbinic literature[3] | c. 100 BCE – 130s CE influence to 5th century CE | References in exoteric Talmud and Midrash to Tannaic early Rabbinic mystical circles, Maaseh Merkabah – Work of the Chariot exegesis and ascent, Maaseh Bereshit – Work of Creation exegesis. Wider continuing mystical elements in aggadah Rabbinic theology and narratives: Johanan ben Zakai and his disciples Rabbi Akiva (Simeon bar Yochai traditional/pseudepigraphical attribution of later Kabbalist Zohar) Mystical aggadot examples: Four who entered the Pardes Oven of Akhnai Bat Kol Torah: black fire on white fire, God looked in Torah to create World Shekhinah accompanies Israel in exile The Messiah at the Gates of Rome |

| Merkabah-Hekhalot esoteric texts and methods | c. 2nd century-1000 | Traditional/pseudepigraphical/anonymous esoteric Merkabah mysticism Throne and Hekhalot Palaces ascent literature and methods. Text protagonists are early Tannaic Rabbis, though texts academically dated variously from Talmudic 100–500 to Gaonic 400–800 periods, and sectarian/rabbinic origins debated: Earlier texts: 3 Enoch Hekhalot Rabbati (The Greater Palaces) Hekhalot Zutari (The Lesser Palaces) Merkavah Rabbah (The Great Chariot) Later texts: Shi'ur Qomah (Divine Dimensions)  |

| Proto-Kabbalistic | 200–600 | Maaseh Bereshit – Creation speculation text. Describes 10 sephirot, though without their significance to later Kabbalah. Received rationalist interpretations before becoming a source text for Kabbalah: Sefer Yetzirah (Book of Formation) |

| Mystical elements in Medieval Jewish philosophy | 11th–13th centuries | Mystical elements in the thought of Medieval rationalist Jewish philosophical theologians: Judah Halevi[4] Moses Maimonides[5] |

| Jewish Sufi piety | 11th to 15th centuries | Jewish piety, including meditative experiential elements: Bahya ibn Paquda 11th century – Chovot HaLevavot (Duties of the Heart) Abraham Maimonides and the "Jewish Sufis" of Cairo 13th–15th century |

| Early Kabbalah | c. 1174–1200 | Emergence of Kabbalistic mystical theosophy in Southern France. The Bahir, regarded in academia as the first Kabbalistic work, incorporates an earlier source text: Sefer HaBahir (Book of Brightness) School of Isaac the Blind |

| Chassidei Ashkenaz | c. 1150–1250 | Mystical-ethical piety and speculative theory in Ashkenaz-Germany. Shaped by Merkabah-Hekhalot texts, Practical Kabbalah magical elements, Rhineland Crusader persecutions and German monastic values: Samuel of Speyer Judah of Regensburg – Sefer Hasidim (Book of the Pious) Eleazar of Worms |

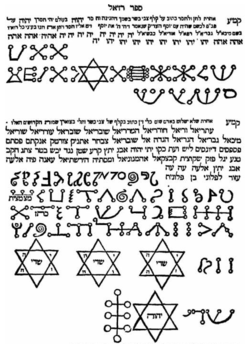

| Medieval Kabbalah development | c. 1200–1492 | Alternative philosophical vs. mythological interpretations of Kabbalistic theosophy: "Neoplatonic" quasi-philosophical hierarchy, and Jewish-"Gnostic" mythological interest in the demonic motifs. Centred in Spain's Kabbalistic golden age: Early 13th century Girona neoplatonic school: Azriel of Gerona Nahmanides (Ramban) – Torah commentary 13th century Castile gnostic school: Treatise on the Left Emanation  The Zohar in Spain from c.1286: Moses de León – Sefer HaZohar (Book of Splendour). Castile's gnostic culmination. Subsequent Zohar exegesis dominated other Medieval Kabbalah traditions Kabbalistic scholarship: Joseph Gikatilla – Shaarei Orah (Gates of Light) c.1290 Spain Sefer HaTemunah (Book of the Figure) 13th–14th century influential doctrine in Kabbalah of Cosmic Cycles, later rejected by Cordovero and Luria[6]  Practical-magical Kabbalah: Sefer Raziel HaMalakh |

| Medieval Prophetic and Meditative Kabbalah | 13th – 16th centuries | Medieval Meditative Kabbalah developed its own traditions.[7] Abraham Abulafia's meditative system of Prophetic Kabbalah, his alternative to the Theosophical Kabbalah, embodies the non-Zoharic ecstatic stream in Spanish Kabbalism: Abulafian Prophetic Kabbalah school: Abraham Abulafia Mediterranean area late 13th century Judah Albotini Jerusalem 15th–16th century Other meditative methods: Isaac of Acco 14th century Joseph Tzayach Damascus and Jerusalem 16th century |

| Post-1492 and Safed Kabbalah | 16th century | Transition from esoteric Medieval Kabbalism to Kabbalah as a national messianic doctrine, after 1492 Expulsion from Spain exile. Jewish renaissance of Palestine: Meir ibn Gabbai 16th century early systemiser Safed-Galilee Kabbalists: Joseph Karo legalist and mystic Shlomo Alkabetz Moses Cordovero (Ramak) – Pardes Rimonim. Cordoverian systemisation of Medieval Kabbalah until 1570 Isaac Luria (the Ari) – new post-Medieval Lurianic systemisation taught 1570–1572 Hayim Vital main Lurianic compiler and other writings Safed Meditative Kabbalah: Vital – Shaarei Kedusha (Gates of Holiness), Luria – Yichudim method |

| Maharal's mystical theology | 16th century | Medieval Kabbalah expressed in non-Kabbalistic philosophical theology: Judah Loew (Maharal) Prague |

| Early Lurianic and post-medieval Kabbalism | 16th-mid-18th centuries | Lurianism, the second of Kabbalah's two systems of theosophy after Medieval-Cordoverian Kabbalah, incorporating dynamic myth of exile and redemption in divinity taught by Isaac Luria 1570–72, and other post-medieval Kabbalah trends: Disciples compile Kitvei Ari Lurianic thought: Hayim Vital – Etz Hayim (Tree of Life) Israel Sarug spread Lurianism in Europe Lurianic exegesis and meditative methods dominated other post-medieval Kabbalah trends Popularising Kabbalistic Musar and homiletic literature 1550s–1750s: Moses Cordovero – Tomer Devorah (Palm Tree of Deborah) Eliyahu de Vidas – Reshit Chochmah (Beginning of Wisdom) Isaiah Horowitz (Shelah) – Shnei Luchot HaBrit (Tablets of the Covenant) Central Europe Kabbalistic scholarship: Moshe Chaim Luzzatto (Ramchal) Italian early 18th century public dissemination of Kabbalah Joseph Ergas  Central-Eastern Europe Practical Kabbalah: Baal Shem |

| Sabbatean movements | 1665 – c. 19th century | Kabbalistic messianic-mystical antinomian heresy: Sabbatai Zevi messianic claimant Nathan of Gaza Sabbatean prophet Moderate-crypto and radical-antinomian factions Emden-Eybeschutz controversy and Rabbinic excommunication of Sabbateans Sabbatean successors culminating in Jacob Frank-late 18th century Frankist nihilism |

| Early and formative Hasidic Judaism | 1730s–1850s | Eastern European mystical revival movement, popularising and psychologising Kabbalah through Panentheism and the Tzadik mystical leader. Neutralised messianic danger expressed in Sabbateanism: Early Hasidism: Israel ben Eliezer (Baal Shem Tov, Besht) founder of Hasidism Dov Ber of Mezeritch (The Magid) systemiser and architect of Hasidism Jacob Joseph of Polonne Levi Yitzhak of Berditchev  Main Hasidic schools of thought (mystics after 1850s shown later): Mainstream Hasidic Tzadikism: Elimelech of Lizhensk – Noam Elimelech (Pleasantness of Elimelech) Yaakov Yitzchak of Lublin (The Chozeh) Chabad intellectual Hasidism – Russia: Shneur Zalman of Liadi – Tanya (Likutei Amarim-Collected Words) theorist of Hasidism[8] Aaron of Staroselye Breslav imaginative Hasidism – Ukraine: Nachman of Breslav – Likutei Moharan (Collected teachings) Nathan of Breslav Peshischa-Kotzk introspective Hasidism – Poland, mystical offshoot from: Mordechai Yosef Leiner of Izbica – Mei Hashiloach (Waters of Shiloah), personal illumination  Hasidic storytelling: Shivchei HaBesht (Praises of the Besht) published 1814 Sippurei Ma'asiyot (Stories that were told) Nachman of Breslav's 13 mystical tales 1816 |

| Later traditional Lurianic Kabbalah | 18th century-today | Traditionalist esoteric interpretations and practice of Lurianic Kabbalah from 18th century until today, apart from Hasidic adaptions: Brody Kloiz and pre-Hasidic Hasidim circles in Eastern Europe. Introverted esotericism response to Sabbatean heresy  Mitnagdic-Lithuanian non-Hasidic Kabbalah: Elijah ben Shlomo Zalman (Vilna Gaon, Gra) figurehead of Mitnagdim 18th century Chaim of Volozhin – Nefesh HaChaim (Soul of Life) theorist of Mitnagdism,[8] founder of Yeshiva movement Mizrahi-Sephardi Oriental Kabbalah: Shalom Sharabi 18th century (from Yemen) and Beit El Synagogue (Jerusalem) introverted esotericism response to Sabbateanism. Lurianic explanation and elite meditation circle Yosef Hayyim (Ben Ish Chai) 19th century Hakham Baghdad Abuhatzeira Moroccan Kabbalist dynasty 20th century Ashkenazi European Kabbalah (apart from Hasidic thought): Shaar Hashamayim Yeshiva (Jerusalem) Yehuda Ashlag 20th century Israel – HaSulam (The Ladder) Lurianic Zohar |

| Later Hasidic Judaism | 1850s-today | Dynastic succession and modernising society turned Hasidism away from pre-1810s mystical revivalism, to post-1850s consolidation and rabbinic conservatism. Mystical focus continued in some schools: Chabad-Lubavitch – intellectual Hasidism communication Zadok HaKohen late 19th century Izbica school Aharon Roth early 20th century Jerusalem piety Kalonymus Kalman Shapira response to Holocaust Menachem Mendel Schneerson (Lubavitch Rebbe) Hasidic outreach and 1990s messianism Breslav contemporary mystical revivalism |

| Neo-Hasidism and Neo-Kabbalah | c. 20th century-today | Non-Orthodox Jewish denominations' adapted spiritual teaching of Kabbalistic and Hasidic theology to modernist thought and interpretations: Early 20th century: Martin Buber existential Neo-Hasidism Post War and contemporary: Abraham Joshua Heschel Neo-traditional aggadic Judaism Zalman Schachter-Shalomi Jewish Renewal Arthur Green academic and theologian Lawrence Kushner Reform Neo-Kabbalah Influence on modern and postmodern Jewish philosophy: Jewish existentialism Postmodern Jewish philosophy[9] Independent scholarship: Sanford Drob – The New Kabbalah[10] |

| Zionist mysticism | c. 1910s-today | Teachings and influence of Rav Kook poetic mystic. Unity of religion and secularism, halakha and aggadah, activism and quietism: Abraham Isaac Kook Chief Rabbi Mandate Palestine Atchalta De'Geulah religious Zionism |

| Academic study of Jewish mysticism | c. 1920s-today | Critical-historical study of Jewish mystical texts began in 19th century, but Gershom Scholem's school in the mid-20th century founded the methodological disciple in academia, returning mysticism to a central position in Jewish historiography and Jewish studies departments. Select historian examples: First generation: Gershom Scholem discipline founder Hebrew University Alexander Altmann American initiator Second generation: Moshe Idel Hebrew University revisionism Joseph Dan Hebrew University Scholem chair |

See also

- Jewish mystical exegesis

- Kabbalah: Primary texts

- List of Jewish Kabbalists

- List of Jewish mysticism scholars

Notes

- ↑ Structure of the table based on an expanded version of the table in Kabbalistic Metaphors: Jewish Mystical Themes in Ancient and Modern Thought, Sanford L. Drob, Jason Aronson, 2000; "The Historical Context" p.2-4

- ↑ There is academic debate whether Prophetic Judaism is phenomenologically a mysticism. While the prophets differed from many (not Hasidic) Jewish mystics in their social role, there are mystical passages in the prophetic books; eg. Ezekiel 1 became the basis of Merkabah mysticism. The Talmud says that there were hundreds of thousands of prophets among Israel: twice as many as the 600,000 Israelites who left Egypt; but most conveyed messages solely for their own generation, so were not reported in scripture (Judaism 101-Prophets and Prophecy). Scripture identifies only 55 prophets of Israel. In Meditation and the Bible, Aryeh Kaplan reconstructs meditative-mystical methods of the Jewish prophetic schools.

- ↑ There is academic debate about how the mystical references in early exoteric Rabbinic literature relate to, or the degree it can be identified with, the mysticism and methods of subsequent esoteric Merkabah-Hekhalot texts.

- ↑ Maimonides' Confrontation with Mysticism, Menachem Kellner, Littman Library: describes Judah Halevi as "Proto-Kabbalistic" in his conception of prophecy and Jewish chosenness in the Kuzari

- ↑ While Menachem Kellner reads Maimonides as anti-"Proto-Kabbalah" (Maimonides' Confrontation with Mysticism, Littman Library), David R. Blumenthal (Philosophic Mysticism and anthologies) reads Maimonides as a rationalist mystic: "The thesis of the book is that medieval philosophers had a type of religious mysticism that was rooted in, yet grew out of, their rationalist thinking. The religious experience of "philosophic mysticism" was the result of this intellectualist and post-intellectualist effort." ()

- ↑ The shemitot and the age of the universe, 3 part video class from inner.org

- ↑ Traditionalist historiography Meditation and Kabbalah, Aryeh Kaplan, Samuel Weiser publishers; overview of the Meditative schools in Kabbalah. Some medieval Meditative Kabbalists also followed the Theosophical Kabbalah, though not its greatest exponent Abulafia in his esoteric system. In turn, the 16th century Safed culmination of theosophy by Cordovero, Luria and Vital dominated and subsumed the previous divergent Kabbalistic streams into their meditative methods, drawing from the earlier schools. After Luria, Meditative Kabbalah followed his new system of Yichudim. In Kabbalah: New Perspectives, Yale University Press 1988, chapter 5 Mystical Techniques, Moshe Idel reinstates the meditative and experiential dimensions of Kabbalah as an inherent companion to the theosophical in academic historiography. Kabbalists often attributed their theosophical doctrines to new meditative revelations.

- 1 2 Torah Lishmah-Torah for Torah's Sake, Norman Lamm, Ktav 1989; summarised in Faith and Doubt, Norman Lamm, chapter "Monism for Moderns". Identifies Chaim of Volozhin as the main kabbalistic-theological theorist of Mitnagdism, and Schneur Zalman of Liadi as the main theorist of Hasidism, based on interpretation of Lurianic Tzimtzum. For Chaim Volozhin, Divine immanence is monistic (the acosmic way God looks at the world, reserved for man only in elite kabbalistic prayer) and Divine transcendence is pluralistic (man relates to God through pluralistic Jewish law), leading to Mitnagdic transcendent Theism and popular ideological Talmudic study focus. For Shneur Zalman, Immanence is pluralistic (man relates to mystical Divine immanence in pluralist Nature) and Transcendence is monistic (Habad Hasidic meditation on acosmic nullification of world from God's perspective), leading to Hasidic Panentheism and popular mysticism Deveikut fervour amidst materiality

- ↑ Reasoning After Revelation: Dialogues in Postmodern Jewish Philosophy, Steven Kepnes – Peter Ochs – Robert Gibbs, Westview Press 2000. "Postmodern Jewish thinkers understand their Jewishness differently, but they all share a fidelity to what they call the Torah and to communal practices of reading and social action that have their bases in rabbinic interpretations of biblical narrative, law, and belief. Thus, postmodern Jewish thinking is thinking about God, Jews, and the world—with the texts of the Torah—in the company of fellow seekers and believers. It utilizes the tools of philosophy, but without their modern premises." Commentaries in later chapters describe the contribution of Kabbalistic mythological thinking to this project.

- ↑ newkabbalah.com

References

- Heschel, Abraham Joshua Heavenly Torah: As Refracted through the Generations, edited and translated by Gordon Tucker, Bloomsbury Academic 2006

- Jacobs, Louis Jewish Mystical Testimonies, Schocken

- Kaplan, Aryeh Meditation and the Bible, Red Wheel/Weiser 1978

- Scholem, Gershom Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, Schocken, first pub.1941

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jewish mysticism. |

- Don Karr's Bibliographic Surveys of contemporary academic scholarship on all periods of Jewish mysticism

- Abraham Joshua Heschel's view of Rabbinic Judaism as aggadah and mystical experience