Society of Jesus

| |

| Abbreviation | S.J., Jesuits, Jebs, Jebbies |

|---|---|

| Motto |

Ad maiorem Dei gloriam For the Greater Glory of God |

| Formation | 27 September 1540 |

| Founder |

Ignatius of Loyola Francis Xavier Peter Faber |

| Founded at |

Paris, France officialized in Rome |

| Type | Catholic religious order |

| Location |

|

| Coordinates | 41°54′4.9″N 12°27′38.2″E / 41.901361°N 12.460611°ECoordinates: 41°54′4.9″N 12°27′38.2″E / 41.901361°N 12.460611°E |

Members | 16,378[1] |

| Arturo Sosa | |

| Website |

www |

| Remarks | Church of the Gesù is the Mother Church of the Jesuits, where Ignatius had his office |

| Part of a series on the |

| Society of Jesus |

|---|

Christogram of the Jesuits |

| History |

| Hierarchy |

| Spirituality |

| Notable Jesuits |

|

|

The Society of Jesus (S.J. – from Latin: Societas Iesu) is a religious congregation of the Catholic Church which originated in Spain. The members are called Jesuits.[2] The society is engaged in evangelization and apostolic ministry in 112 nations on six continents. Jesuits work in education (founding schools, colleges, universities, and seminaries), intellectual research, and cultural pursuits. Jesuits also give retreats, minister in hospitals and parishes, sponsor direct social ministries, and promote ecumenical dialogue.

Ignatius of Loyola, a Basque nobleman from the Pyrenees area of northern Spain, founded the society after discerning his spiritual vocation while recovering from a wound sustained in the Battle of Pamplona. He composed the Spiritual Exercises to help others follow the teachings of Jesus Christ. In 1534, Ignatius and six other young men, including Francis Xavier and Peter Faber, gathered and professed vows of poverty, chastity, and later obedience, including a special vow of obedience to the Pope in matters of mission direction and assignment. Ignatius's plan of the order's organization was approved by Pope Paul III in 1540 by a bull containing the "Formula of the Institute".

Ignatius was a nobleman who had a military background, and the members of the society were supposed to accept orders anywhere in the world, where they might be required to live in extreme conditions. Accordingly, the opening lines of the founding document declared that the society was founded for "whoever desires to serve as a soldier of God[lower-alpha 1] to strive especially for the defence and propagation of the faith and for the progress of souls in Christian life and doctrine."[4] Jesuits are thus sometimes referred to colloquially as "God's soldiers",[5] "God's marines",[6] or "the Company", which evolved from references to Ignatius' history as a soldier and the society's commitment to accepting orders anywhere and to endure any conditions.[7] The society participated in the Counter-Reformation and, later, in the implementation of the Second Vatican Council.

The Society of Jesus is consecrated under the patronage of Madonna Della Strada, a title of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and it is led by a Superior General.[8][9] The headquarters of the society, its General Curia, is in Rome.[10] The historic curia of St. Ignatius is now part of the Collegio del Gesù attached to the Church of the Gesù, the Jesuit mother church.

In 2013, Jorge Mario Bergoglio became the first Jesuit Pope, taking the name Pope Francis.

Statistics

| Region | Jesuits | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 1,509 | 9% |

| South Latin America | 1,221 | 7% |

| North Latin America | 1,226 | 7% |

| South Asia | 4,016 | 23% |

| Asia-Pacific | 1,639 | 9% |

| Central and East Europe | 1,641 | 10% |

| South Europe | 2,027 | 12% |

| West Europe | 1,541 | 9% |

| North America | 2,467 | 14% |

The Jesuits today form the largest single religious order of priests and brothers in the Catholic Church,[13] (although they are surpassed by the Franciscan family of orders of Friars Minor, Capuchins, and Conventuals). The Jesuits have experienced a decline in numbers in recent decades. As of 2016 the society had 16,378 members, 11,785 priests and 4,593 brothers and scholastics. This represents a 41.5% decline since 1977, when the society had a total membership of 28,038, of which, 20,205 were priests.[1] This decline is most pronounced in Europe and the Americas, with relatively modest membership gains occurring in Asia and Africa.[14][15] There seems to be no "Pope Francis effect" in counteracting the free fall of vocations among the Jesuits.[16]

The society is divided into 83 provinces along with six independent regions and ten dependent regions.[11] On 1 January 2007, members served in 112 nations on six continents with the largest number in India and the US. Their average age was 57.3 years: 63.4 years for priests, 29.9 years for scholastics, and 65.5 years for brothers.[17]

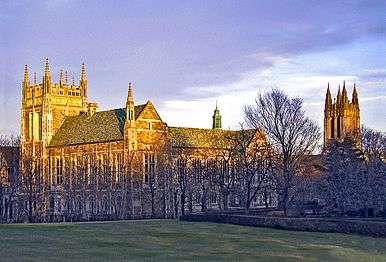

The current Superior General of the Jesuits is Arturo Sosa. The society is characterized by its ministries in the fields of missionary work, human rights, social justice and, most notably, higher education. It operates colleges and universities in various countries around the world and is particularly active in the Philippines and India. In the United States it maintains 28 colleges and universities and 61 high schools. Worldwide it runs 322 secondary schools and 172 colleges and universities. A typical conception of the mission of a Jesuit school will often contain such concepts as proposing Christ as the model of human life, the pursuit of excellence in teaching and learning, lifelong spiritual and intellectual growth,[18] and training men and women for others.[19]

Formula of the Institute

Ignatius laid out his original vision for the new order in the "Formula of the Institute of the Society of Jesus",[20] which is "the fundamental charter of the order, of which all subsequent official documents were elaborations and to which they had to conform."[21] He ensured that his formula was contained in two papal bulls signed by Pope Paul III in 1540 and by Pope Julius III in 1550.[20] The formula expressed the nature, spirituality, community life, and apostolate of the new religious order. Its famous opening statement echoed Ignatius' military background:

Whoever desires to serve as a soldier of God beneath the banner of the Cross in our Society, which we desire to be designated by the Name of Jesus, and to serve the Lord alone and the Church, his spouse, under the Roman Pontiff, the Vicar of Christ on earth, should, after a solemn vow of perpetual chastity, poverty and obedience, keep what follows in mind. He is a member of a Society founded chiefly for this purpose: to strive especially for the defence and propagation of the faith and for the progress of souls in Christian life and doctrine, by means of public preaching, lectures and any other ministration whatsoever of the Word of God, and further by means of retreats, the education of children and unlettered persons in Christianity, and the spiritual consolation of Christ's faithful through hearing confessions and administering the other sacraments. Moreover, he should show himself ready to reconcile the estranged, compassionately assist and serve those who are in prisons or hospitals, and indeed, to perform any other works of charity, according to what will seem expedient for the glory of God and the common good.[17]

A fresco depicting Ignatius of Loyola receiving the papal bull Regimini militantis Ecclesiae from Pope Paul III was created after 1743 by Johann Christoph Handke in the Church of Our Lady Of the Snow in Olomouc.

History

Foundation

On 15 August 1534, Ignatius of Loyola (born Íñigo López de Loyola), a Spaniard from the Basque city of Loyola, and six others mostly of Castilian origin, all students at the University of Paris,[22] met in Montmartre outside Paris, in a crypt beneath the church of Saint Denis, now Saint Pierre de Montmartre, to pronounce the religious vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.[23] Ignatius' six companions were: Francisco Xavier from Navarre (modern Spain), Alfonso Salmeron, Diego Laínez, Nicolás Bobadilla from Castile (modern Spain), Peter Faber from Savoy, and Simão Rodrigues from Portugal.[24] The meeting has been commemorated in the Martyrium of Saint Denis, Montmartre. They called themselves the Compañía de Jesús, and also Amigos en El Señor or "Friends in the Lord", because they felt "they were placed together by Christ." The name "company" had echoes of the military (reflecting perhaps Ignatius' background as Captain in the Spanish army) as well as of discipleship (the "companions" of Jesus). The Spanish "company" would be translated into Latin as societas like in socius, a partner or comrade. From this came "Society of Jesus" (SJ) by which they would be known more widely.[25]

Religious orders established in the medieval era were named after particular men: Francis of Assisi (Franciscans), Domingo de Guzmán, later canonized as St Dominic (Dominicans); and Augustine of Hippo (Augustinians). Ignatius of Loyola and his followers appropriated the name of Jesus for their new order, provoking resentment by other religious who considered it presumptuous. The resentment was recorded by Jesuit José de Acosta of a conversation with the Archbishop of Santo Domingo.[26] In the words of one historian: "The use of the name Jesus gave great offense. Both on the Continent and in England, it was denounced as blasphemous; petitions were sent to kings and to civil and ecclesiastical tribunals to have it changed; and even Pope Sixtus V had signed a Brief to do away with it." But nothing came of all the opposition; there were already congregations named after the Trinity and as "God's daughters".[27]

In 1537, the seven travelled to Italy to seek papal approval for their order. Pope Paul III gave them a commendation, and permitted them to be ordained priests. These initial steps led to the official founding in 1540 .

They were ordained at Venice by the bishop of Arbe (24 June). They devoted themselves to preaching and charitable work in Italy. The Italian War of 1535-1538 renewed between Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Venice, the Pope, and the Ottoman Empire, had rendered any journey to Jerusalem impossible.

Again in 1540, they presented the project to Paul III. After months of dispute, a congregation of cardinals reported favourably upon the Constitution presented, and Paul III confirmed the order through the bull Regimini militantis ecclesiae ("To the Government of the Church Militant"), on 27 September 1540. This is the founding document of the Society of Jesus as an official Catholic religious order. Ignatius was chosen as the first Superior General. Paul III's bull had limited the number of its members to sixty. This limitation was removed through the bull Exposcit debitum of Julius III in 1550.[28]

In fulfilling the mission of the "Formula of the Institute of the Society", the first Jesuits concentrated on a few key activities. First, they founded schools throughout Europe. Jesuit teachers were trained in both classical studies and theology, and their schools reflected this. Second, they sent out missionaries across the globe to evangelize those peoples who had not yet heard the Gospel, founding missions in widely diverse regions such as modern-day Paraguay, Japan, Ontario, and Ethiopia. One of the original seven arrived in India already in 1541.[29] Finally, though not initially formed for the purpose, they aimed to stop Protestantism from spreading and to preserve communion with Rome and the successor of Peter. The zeal of the Jesuits overcame the movement toward Protestantism in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and southern Germany.

Ignatius wrote the Jesuit Constitutions, adopted in 1553, which created a centralised organization and stressed acceptance of any mission to which the Pope might call them.[30][31][32] His main principle became the unofficial Jesuit motto: Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam ("For the greater glory of God"). This phrase is designed to reflect the idea that any work that is not evil can be meritorious for the spiritual life if it is performed with this intention, even things normally considered of little importance.[28]

The Society of Jesus is classified among institutes as a mendicant order of clerks regular, that is, a body of priests organized for apostolic work, following a religious rule, and relying on alms, or donations, for support.

The term "Jesuit" (of 15th-century origin, meaning one who used too frequently or appropriated the name of Jesus) was first applied to the society in reproach (1544–52).[33] The term was never used by Ignatius of Loyola, but over time, members and friends of the society adopted the name with a positive meaning.[27]

Early works

The Jesuits were founded just before the Council of Trent (1545–1563) and ensuing Counter-Reformation that would introduce reforms within the Catholic Church, and so counter the Protestant Reformation throughout Catholic Europe.

Ignatius and the early Jesuits did recognize, though, that the hierarchical church was in dire need of reform. Some of their greatest struggles were against corruption, venality, and spiritual lassitude within the Catholic Church. Ignatius insisted on a high level of academic preparation for the clergy in contrast to the relatively poor education of much of the clergy of his time. And the Jesuit vow against "ambitioning prelacies" can be seen as an effort to counteract another problem evidenced in the preceding century.

St. Ignatius and the Jesuits who followed him believed that the reform of the church had to begin with the conversion of an individual's heart. One of the main tools the Jesuits have used to bring about this conversion is the Ignatian retreat, called the Spiritual Exercises. During a four-week period of silence, individuals undergo a series of directed meditations on the purpose of life and contemplations on the life of Christ. They meet regularly with a spiritual director who guides their choice of exercises and helps them to develop a more discerning love for Christ.

The retreat follows a "Purgative-Illuminative-Unitive" pattern in the tradition of the spirituality of John Cassian and the Desert Fathers. Ignatius' innovation was to make this style of contemplative mysticism available to all people in active life. Further, he used it as a means of rebuilding the spiritual life of the church. The Exercises became both the basis for the training of Jesuits and one of the essential ministries of the order: giving the exercises to others in what became known as "retreats".

The Jesuits' contributions to the late Renaissance were significant in their roles both as a missionary order and as the first religious order to operate colleges and universities as a principal and distinct ministry. By the time of Ignatius' death in 1556, the Jesuits were already operating a network of 74 colleges on three continents. A precursor to liberal education, the Jesuit plan of studies incorporated the Classical teachings of Renaissance humanism into the Scholastic structure of Catholic thought.

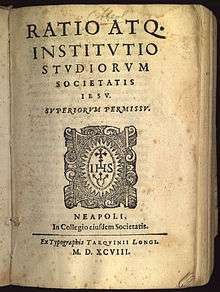

In addition to the teachings of faith, the Jesuit Ratio Studiorum (1599) would standardize the study of Latin, Greek, classical literature, poetry, and philosophy as well as non-European languages, sciences, and the arts. Furthermore, Jesuit schools encouraged the study of vernacular literature and rhetoric, and thereby became important centres for the training of lawyers and public officials.

The Jesuit schools played an important part in winning back to Catholicism a number of European countries which had for a time been predominantly Protestant, notably Poland and Lithuania. Today, Jesuit colleges and universities are located in over one hundred nations around the world. Under the notion that God can be encountered through created things and especially art, they encouraged the use of ceremony and decoration in Catholic ritual and devotion. Perhaps as a result of this appreciation for art, coupled with their spiritual practice of "finding God in all things", many early Jesuits distinguished themselves in the visual and performing arts as well as in music. The theater was a form of expression especially prominent in Jesuit schools.[34]

Jesuit priests often acted as confessors to kings during the Early Modern Period. They were an important force in the Counter-Reformation and in the Catholic missions, in part because their relatively loose structure (without the requirements of living and celebration of the Liturgy of Hours in common) allowed them to be flexible and meet diverse needs arising at the time.[35]

Expansion

Early missions in Japan resulted in the government granting the Jesuits the feudal fiefdom of Nagasaki in 1580. However, this was removed in 1587 due to fears over their growing influence.

Francis Xavier, one of the original companions of Loyola, arrived in Goa, in Portuguese India, in 1541 to consider evangelical service in the Indies. In a 1545 letter to John III of Portugal, he requested an Inquisition to be installed in Goa (see Goa Inquisition). He died in China after a decade of evangelism in Southern India. The Portuguese Jesuit, António de Andrade founded a mission in Western Tibet in 1624. Two Jesuit missionaries, Johann Grueber and Albert Dorville, reached Lhasa in Tibet in 1661. The Italian Jesuit Ippolito Desideri established a new Jesuit mission in Lhasa and Central Tibet (1716–21) and gained an exceptional mastery of Tibetan language and culture, writing a long and very detailed account of the country and its religion as well as treatises in Tibetan that attempted to refute key Buddhist ideas and establish the truth of Roman Catholic Christianity.

Jesuit missions in America became controversial in Europe, especially in Spain and Portugal where they were seen as interfering with the proper colonial enterprises of the royal governments. The Jesuits were often the only force standing between the Native Americans and slavery. Together throughout South America but especially in present-day Brazil and Paraguay, they formed Christian Native American city-states, called "reductions". These were societies set up according to an idealized theocratic model. The efforts of Jesuits like Antonio Ruiz de Montoya to protect the natives from enslavement by Spanish and Portuguese colonizers would contribute to the call for the society's suppression. Jesuit priests such as Manuel da Nóbrega and José de Anchieta founded several towns in Brazil in the 16th century, including São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, and were very influential in the pacification, religious conversion, and education of Indian nations.

Jesuit scholars working in foreign missions were very important in studying their languages and strove to produce Latinized grammars and dictionaries. This included: Japanese (see Nippo jisho also known as Vocabvlario da Lingoa de Iapam, Vocabulary of the Japanese Language, a Japanese–Portuguese dictionary written 1603); Vietnamese (French Jesuit missionary Alexandre de Rhodes formalized the Vietnamese alphabet in use today with his 1651 Vietnamese–Portuguese–Latin dictionary Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum); Tupi (the main language of Brazil); and the pioneering study of Sanskrit in the West by Jean François Pons in the 1740s.

Under Portuguese royal patronage, Jesuits thrived in Goa and until 1759 successfully expanded their activities to education and healthcare. In 1594 they founded the first Roman-style academic institution in the East, St. Paul Jesuit College in Macau, China. Founded by Alessandro Valignano, it had a great influence on the learning of Eastern languages (Chinese and Japanese) and culture by missionary Jesuits, becoming home to the first western sinologists such as Matteo Ricci. Jesuit efforts in Goa were interrupted by the expulsion of the Jesuits from Portuguese territories in 1759 by the powerful Marquis of Pombal, Secretary of State in Portugal.[36]

Jesuit missionaries were active among indigenous peoples in New France in North America, many of them compiling dictionaries or glossaries of the First Nations and Native American languages they had learned. For instance, before his death in 1708, Jacques Gravier, vicar general of the Illinois Mission in the Mississippi River valley, compiled a Kaskaskia Illinois–French dictionary, considered the most extensive among works of the missionaries.[37] Extensive documentation was left in the form of The Jesuit Relations, published annually from 1632 until 1673.

Activity in China

The Jesuits first entered China through the Portuguese possession of Macau where they founded St. Paul's College of Macau.

The Jesuit China missions of the 16th and 17th centuries introduced Western science and astronomy, then undergoing its own revolution, to China. The scientific revolution brought by the Jesuits coincided with a time when scientific innovation had declined in China:

[The Jesuits] made efforts to translate western mathematical and astronomical works into Chinese and aroused the interest of Chinese scholars in these sciences. They made very extensive astronomical observation and carried out the first modern cartographic work in China. They also learned to appreciate the scientific achievements of this ancient culture and made them known in Europe. Through their correspondence European scientists first learned about the Chinese science and culture.[38]

The Jesuits were very active in transmitting Chinese knowledge and philosophy to Europe. Confucius's works were translated into European languages through the agency of Jesuit scholars stationed in China, which is why Kǒng Fūzǐ is known in the West under his Latinized name to this day.

Matteo Ricci started to report on the thoughts of Confucius, and father Prospero Intorcetta published the life and works of Confucius in Latin in 1687.[39] It is thought that such works had considerable influence on European thinkers of the period, particularly among the Deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment intrigued by the integration of the Confucian system of morality into Catholicism.[40]

The extent to which the Jesuits accommodated Chinese beliefs and rituals resulted in the Chinese Rites controversy. The Vatican's condemnations of these accommodations insulted the Chinese emperors, relations soured, and Jesuits were expelled from China after 1721.[41]

Activity in Canada

During the French colonisation of New France in the 17th century, Jesuits played an active role in North America. When Samuel de Champlain established the foundations of the French colony at Québec, he was aware of native tribes who possessed their own languages, customs, and traditions. These natives that inhabited modern day Ontario, Québec, and the areas around Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay were the Montagnais, the Algonquins, and the Huron.[42] Champlain believed that these has souls to be saved, so in 1614 he initially obtained the Recollects, a reform branch of the Franciscans in France, to convert the native inhabitants.[43] In 1624 the French Recollects realized the magnitude of their task[44] and sent a delegate to France to invite the Society of Jesus to help with this mission. The invitation was accepted, and Jesuits Jean de Brébeuf, Ennemond Masse, and Charles Lalemant arrived in Quebec in 1625.[45] Lalemant is considered to have been the first author of one of the Jesuit Relations of New France, which chronicled their evangelization during the seventeenth century.

The Jesuits became involved in the Huron mission in 1626 and lived among the Huron peoples. Brébeuf learned the native language and created the first Huron language dictionary. Outside conflict forced the Jesuits to leave New France in 1629 when Quebec was captured by the Kirke brothers under the English flag. But in 1632 Quebec was returned to the French under the Treaty of Saint Germain-en-Laye and the Jesuits returned to Huron territory, modern Huronia.[46]

In 1639, Jesuit Jerome Lalemant decided that the missionaries among the Hurons needed a local residence and established Sainte-Marie, which expanded into a living replica of European society.[47] It became the Jesuit headquarters and an important part of Canadian history. Throughout most of the 1640s the Jesuits had great success, establishing five chapels in Huronia and baptising over one thousand Huron natives.[48] However, as the Jesuits began to expand westward they encountered more Iroquois natives, rivals of the Hurons. The Iroquois grew jealous of the Hurons' wealth and fur trade system, began to attack Huron villages in 1648. They killed missionaries and burned villages, and the Hurons scattered. Both Jean de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalemant were tortured and killed in the Iroquois raids; they have been canonized as martyrs in the Catholic Church.[49] With the knowledge of the invading Iroquois, the Jesuit Paul Ragueneau burned down Sainte-Marie instead of allowing the Iroquois the satisfaction of destroying it. By late June 1649, the French and some Christian Hurons built Sainte-Marie II on Christian Island (Isle de Saint-Joseph). However, facing starvation, lack of supplies, and constant threats of Iroquois attack, the small Sainte-Marie II was abandoned in June 1650; the remaining Hurons and Jesuits departed for Quebec and Ottawa.[49] After a series of epidemics, beginning in 1634, some Huron began to mistrust the Jesuits and accused them of being sorcerers casting spells from their books.[50] As a result of the Iroquois raids and outbreak of disease, many missionaries, traders, and soldiers died.[51] Today, the Huron tribe, also known as the Wyandot, have a First Nations reserve in Quebec, Canada, and three major settlements in the United States.[52]

After the collapse of the Huron nation, the Jesuits were to undertake the task of converting the Iroquois, something they had attempted in 1642 with little success. In 1653 the Iroquois nation had a fallout with the Dutch. They then signed a peace treaty with the French and a mission was established. The Iroquois took the treaty lightly and soon turned on the French again. In 1658, the Jesuits were having very little success and were under constant threat of being tortured or killed,[51] but continued their effort until 1687 when they abandoned their permanent posts in the Iroquois homeland.[53]

By 1700, Jesuits turned to maintaining Quebec, Montreal, and Ottawa without establishing new posts.[54] During the Seven Years' War, Quebec fell to the English in 1759 and New France was under British control. The English barred the immigration of more Jesuits to New France. By 1763, there were only twenty-one Jesuits stationed in New France. By 1773 only eleven Jesuits remained. During the same year the English crown laid claim to New France and declared that the Society of Jesus in New France was dissolved.[55]

Activity in the United States

In 1647 the Massachusetts Bay Colony passed a law prohibiting any Jesuit Roman Catholic priests from entering territory under Puritan jurisdiction.[56] Anti-Catholic sentiment had appeared in New England with the first Pilgrim and Puritan settlers.[57] Any suspected Jesuit who could not clear himself was to be banished from the colony; a second offence carried a death penalty.[58] There were about two dozen Jesuits in 1760, and they kept a low profile.[58]

Former Jesuit John Carroll (1735–1815) became the first Catholic archbishop in the young republic. He founded Georgetown University in 1789, and it remains a pre-eminent Jesuit school.[59]

The Jesuit Père Marquette and Louis Jolliet were the first Europeans to explore and chart the northern portion of the Mississippi River, as far as the Illinois River.

Peter De Smet was a Jesuit active in missionary work among the Plains Indians in the mid-19th century. His extensive travels as a missionary were said to total 180,000 miles. He was known as the "Friend of Sitting Bull" because he persuaded the Sioux war chief to participate in negotiations with the United States government for the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

Jesuits in Mexico

The Jesuits in New Spain distinguished themselves in several ways. They had high standards for acceptance to the order and many years of training. They attracted the patronage of elite families whose sons they educated in rigorous newly founded Jesuit colegios ("colleges"), including Colegio de San Pedro y San Pablo, Colegio de San Ildefonso, and the Colegio de San Francisco Javier, Tepozotlan. Those same elite families hoped that a son with a vocation to the priesthood would be accepted as a Jesuit. Jesuits were also zealous in evangelization of the indigenous, particularly on the northern frontiers.

To support their colegios and members of the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits acquired landed estates that were run with the best-practices for generating income in that era. A number of these haciendas were donated by wealthy elites. The donation of a hacienda to the Jesuits was the spark igniting a conflict between seventeenth-century bishop of Puebla Don Juan de Palafox and the Jesuit colegio in that city. Since the Jesuits resisted paying the tithe on their estates, this donation effectively took revenue out of the church hierarchy's pockets by removing it from the tithe rolls.[60]

Many of Jesuit haciendas were huge, with Palafox asserting that just two colleges owned 300,000 head of sheep, whose wool was transformed locally in Puebla to cloth; six sugar plantations worth a million pesos and generating an income of 100,000 pesos.[60] The immense Jesuit hacienda of Santa Lucía produced pulque, the fermented juice of the agave cactus whose main consumers were the lower classes and Indians in Spanish cities. Although most haciendas had a free work force of permanent or seasonal labourers, the Jesuit haciendas in Mexico had a significant number of black slaves.[61]

The Jesuits operated their properties as an integrated unit with the larger Jesuit order; thus revenues from haciendas funded their colegios. Jesuits did significantly expand missions to the indigenous in the northern frontier area and a number were martyred, but the crown supported those missions.[60] Mendicant orders that had real estate were less economically integrated, so that some individual houses were wealthy while others struggled economically. The Franciscans, who were founded as an order embracing poverty, did not accumulate real estate, unlike the Augustinians and Dominicans in Mexico.

The Jesuits engaged in conflict with the episcopal hierarchy over the question of payment of tithes, the ten percent tax on agriculture levied on landed estates for support of the church hierarchy from bishops and cathedral chapters to parish priests. Since the Jesuits were the largest religious order holding real estate, surpassing the Dominicans and Augustinians who had accumulated significant property, this was no small matter.[60] They argued that they were exempt, due to special pontifical privileges.[62] In the mid-seventeenth century, bishop of Puebla, Don Juan de Palafox took on the Jesuits over this matter and was so soundly defeated that he was recalled to Spain, where he became the bishop of the minor diocese of Osma.

As elsewhere in the Spanish empire, the Jesuits were expelled from Mexico in 1767. Their haciendas were sold off and their colegios and missions in Baja California were taken over by other orders.[63] Exiled Mexican-born Jesuit Francisco Javier Clavijero wrote an important history of Mexico while in Italy, a basis for creole patriotism. Andrés Cavo also wrote an important text on Mexican history that Carlos María de Bustamante published in the early nineteenth-century.[64] An earlier Jesuit who wrote about the history of Mexico was Diego Luis de Motezuma (1619–99), a descendant of the Aztec monarchs of Tenochtitlan. Motezuma's Corona mexicana, o Historia de los nueve Motezumas was completed in 1696. He "aimed to show that Mexican emperors were a legitimate dynasty in the 17th-century in the European sense."[65][66]

The Jesuits were allowed to return to Mexico in 1840 when General Antonio López de Santa Anna was once more president of Mexico. Their re-introduction to Mexico was "to assist in the education of the poorer classes and much of their property was restored to them."[67]

Jesuits in northern Spanish America

The Jesuits arrived in the Viceroyalty of Peru by 1571; it was a key area of Spanish empire, with not only dense indigenous populations but also huge deposits of silver at Potosí. A major figure in the first wave of Jesuits was José de Acosta (1540–1600), whose book Historia natural y moral de las Indias (1590) introduced Europeans to Spain's American empire via fluid prose and keen observation and explanation, based on fifteen years in Peru and a bit of time in New Spain (Mexico). Viceroy of Peru Don Francisco de Toledo urged the Jesuits to evangelize the indigenous peoples of Peru, wanting to put them in charge of parishes, but Acosta adhered to the Jesuit position that they were not subject to the jurisdiction of bishops and to catechize in Indian parishes would bring them into conflict with the bishops. For that reason, the Jesuits in Peru focused on education of elite men rather than the indigenous populations.[68]

To minister to newly arrived African slaves, Alonso de Sandoval (1576–1651) worked at the port of Cartagena de Indias. Sandoval wrote about this ministry in De instauranda Aethiopum salute (1627),[69] describing how he and his assistant Pedro Claver, later canonized, met slave transport ships in the harbour, went below decks where 300-600 slaves were chained, and gave physical aid with water, while introducing the Africans to Christianity. In his treatise, he did not condemn slavery or the ill-treatment of slaves, but sought to instruct fellow Jesuits to this ministry and describe how he catechized the slaves.[70]

Rafael Ferrer was the first Jesuit of Quito to explore and found missions in the upper Amazon regions of South America from 1602 to 1610, which belonged to the Audiencia (high court) of Quito that was a part of the Viceroyalty of Peru until it was transferred to the newly created Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1717. In 1602, Ferrer began to explore the Aguarico, Napo, and Marañon rivers (Sucumbios region, in what is today Ecuador and Peru), and between 1604 and 1605 set up missions among the Cofane natives. He was martyred by an apostate native in 1610.

In 1639, the Audiencia of Quito organized an expedition to renew its exploration of the Amazon river and the Quito Jesuit (Jesuita Quiteño) Cristóbal de Acuña was a part of this expedition. The expedition disembarked from the Napo river 16 February 1639 and arrived in what is today Pará Brazil on the banks of the Amazon river on 12 December 1639. In 1641, Acuña published in Madrid a memoir of his expedition to the Amazon river entitled Nuevo Descubrimiento del gran rio de las Amazonas, which for academics became a fundamental reference on the Amazon region.

In 1637, the Jesuits Gaspar Cugia and Lucas de la Cueva from Quito began establishing missions in Maynas territories, on the banks of the Marañón River, around the Pongo de Manseriche region, close to the Spanish settlement of Borja. Between 1637 and 1652 there were 14 missions established along the Marañón River and its southern tributaries, the Huallaga and the Ucayali rivers. Jesuit Lucas de la Cueva and Raimundo de Santacruz opened up two new routes of communication with Quito, through the Pastaza and Napo rivers.

Between 1637 and 1715, Samuel Fritz founded 38 missions along the length of the Amazon river, between the Napo and Negro rivers, that were called the Omagua Missions. These missions were continually attacked by the Brazilian Bandeirantes beginning in the year 1705. In 1768, the only Omagua mission that was left was San Joaquin de Omaguas, since it had been moved to a new location on the Napo river away from the Bandeirantes.

In the immense territory of Maynas, the Jesuits of Quito made contact with a number of indigenous tribes which spoke 40 different languages, and founded a total of 173 Jesuit missions encompassing 150,000 inhabitants. Because of the constant epidemics (smallpox and measles) and warfare with other tribes and the Bandeirantes, the total number of Jesuit Missions were reduced to 40 by 1744. At the time when the Jesuits were expelled from Spanish America in 1767, the Jesuits of Quito registered 36 missions run by 25 Jesuits of Quito in the Audiencia of Quito – 6 in the Napo and Aguarico Missions and 19 in the Pastaza and Iquitos Missions, with the population at 20,000 inhabitants.

Jesuits in Paraguay

The first Jesuits arrived in 1588, and in 1610 Philip III proclaimed that only the "sword of the word" should be used to subdue Paraguayan Indians. The church granted Jesuits extensive powers to phase out the encomienda system of forced labor, angering settlers dependent on a continuing supply of Indian labor and concubines. In one of history's greatest experiments in communal living, the Jesuits had soon organized about 100,000 Guaraní in about 20 reducciones (reductions or townships), and they dreamed of a Jesuit empire that would stretch from the Paraguay-Paraná confluence to the coast and back to the Paraná headwaters.[71]

The new Jesuit reductions were threatened by the slave-raiding mamelucos, who survived by capturing Indians and selling them as slaves to planters in Brazil. Having depleted the Indian population near Sâo Paulo, they discovered the richly populated Reductions. The Spanish authorities chose not to defend the settlements, and the Jesuits and their thousands of neophytes thus had little means to protect themselves. The mameluco threat ended only after 1639, after the capture of thousands of Indian neophytes, when the viceroy of Peru agreed to allow Indians to bear arms. Well-trained and highly motivated Indian units fought the raiders and drove them off. This victory set the stage for the golden age of the Jesuits in Paraguay. Life in the Reductions offered the Guaraní higher living standards, protection from settlers, and physical security. These Reductions, which became quite wealthy, exported goods and supplied Indian armies.[71]

The Reductions, where the Jesuits created orchestras, musical ensembles, and actors' troupes, and in which virtually all the profits derived from Indian labor were distributed to the labourers, earned praise from some of the leaders of the French enlightenment, who were not predisposed to favour Jesuits. "By means of religion," d'Alembert wrote, "the Jesuits established a monarchical authority in Paraguay, founded solely on their powers of persuasion and on their lenient methods of government. Masters of the country, they rendered happy the people under their sway; they succeeded in subduing them without ever having recourse to force." And Jesuit-educated Voltaire called the Jesuit government "a triumph of humanity."[72]

Because of their success, the Paraguayan Jesuits gained many enemies, and the Reductions fell prey to changing times. During the 1720s and 1730s, Paraguayan settlers rebelled against Jesuit privileges in the Revolt of the Comuneros and against the government that protected them. Although this revolt failed, it was one of the earliest and most serious risings against Spanish authority in the New World and caused the crown to question its continued support for the Jesuits. The Jesuit-inspired War of the Seven Reductions (1750–61) increased sentiment in Madrid for suppressing this "empire within an empire."

The Spanish king Charles III (1759–88) expelled the Jesuits in 1767 from Spain and its territories. Within a few decades of the expulsion, most of what the Jesuits had accomplished was lost. The missions were mismanaged and abandoned by the Guaraní. Today, these ruins of a 160-year experiment have become a tourist attraction.[71][73]

Jesuits in colonial Brazil

Tomé de Sousa, first Governor General of Brazil, brought the first group of Jesuits to the colony. The Jesuits were officially supported by the King, who instructed Tomé de Sousa to give them all the support needed to Christianize the indigenous peoples.

The first Jesuits, guided by Manuel da Nóbrega, Juan de Azpilcueta Navarro, Leonardo Nunes, and later José de Anchieta, established the first Jesuit missions in Salvador and in São Paulo dos Campos de Piratininga, the settlement that gave rise to the city of São Paulo. Nóbrega and Anchieta were instrumental in the defeat of the French colonists of France Antarctique by managing to pacify the Tamoio natives, who had previously fought the Portuguese. The Jesuits took part in the foundation of the city of Rio de Janeiro in 1565.

The success of the Jesuits in converting the indigenous peoples is linked to their efforts to understand the native cultures, especially their languages. The first grammar of the Tupi language was compiled by José de Anchieta and printed in Coimbra in 1595. The Jesuits often gathered the aborigines in communities (the Jesuit Reductions) where the natives worked for the community and were evangelised.

The Jesuits had frequent disputes with other colonists who wanted to enslave the natives. The action of the Jesuits saved many natives from being enslaved by Europeans, but also disturbed their ancestral way of life and inadvertently helped spread infectious diseases against which the aborigines had no natural defenses. Slave labor and trade were essential for the economy of Brazil and other American colonies, and the Jesuits usually did not object to the enslavement of African peoples, but rather critiqued the conditions of slavery.[74]

Suppression and restoration

The Suppression of the Jesuits in Portugal, France, the Two Sicilies, Parma, and the Spanish Empire by 1767 was troubling to the society's defender, Pope Clement XIII. On 21 July 1773 Pope Clement XIV issued the papal brief Dominus ac Redemptor,[75] decreeing:

Having further considered that the said Company of Jesus can no longer produce those abundant fruits, ... in the present case, we are determining upon the fate of a society classed among the mendicant orders, both by its institute and by its privileges; after a mature deliberation, we do, out of our certain knowledge, and the fulness of our apostolical power, suppress and abolish the said company: we deprive it of all activity whatever. ...And to this end a member of the regular clergy, recommendable for his prudence and sound morals, shall be chosen to preside over and govern the said houses; so that the name of the Company shall be, and is, for ever extinguished and suppressed.

The suppression was carried out in all countries except Prussia and Russia, where Catherine the Great had forbidden its promulgation. Because millions of Catholics (including many Jesuits) lived in the Polish provinces recently annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia, the society was able to maintain its existence and carry on its work all through the period of suppression. Subsequently, Pope Pius VI would grant formal permission for the continuation of the society in Russia and Poland, with Stanislaus Czerniewicz elected superior of the society in 1782. Pope Pius VII had resolved during his captivity in France to restore the Jesuits universally, and after his return to Rome he did so with little delay. On 7 August 1814, by the bull Sollicitudo omnium ecclesiarum, he reversed the suppression of the society, and therewith another Polish Jesuit, Thaddeus Brzozowski, who had been elected in Superior in Russia in 1805, acquired universal jurisdiction.

The period following the Restoration of the Jesuits in 1814 was marked by tremendous growth, as evidenced by the large number of Jesuit colleges and universities established in the 19th century. In the United States, 22 of the society's 28 universities were founded or taken over by the Jesuits during this time. It has been suggested that the experience of suppression served to heighten orthodoxy among the Jesuits upon restoration. While this claim is debatable, Jesuits were generally supportive of papal authority within the church, and some members were associated with the Ultramontanist movement and the declaration of Papal Infallibility in 1870.

In Switzerland, following the defeat of the Sonderbund Catholic defense alliance, the constitution was modified and Jesuits were banished in 1848. The ban was lifted on 20 May 1973, when 54.9% of voters accepted a referendum modifying the Constitution.[76]

Early 20th century

In the Constitution of Norway from 1814, a relic from the earlier anti-Catholic laws of Denmark-Norway, Paragraph 2 originally read: "The Evangelical-Lutheran religion remains the public religion of the State. Those inhabitants, who confess thereto, are bound to raise their children to the same. Jesuits and monastic orders are not permitted. Jews are still prohibited from entry to the Realm." Jews were first allowed into the Realm in 1851 after the famous Norwegian poet Henrik Wergeland had campaigned for it. Monastic orders were permitted in 1897, but the ban on Jesuits was only lifted in 1956.

Republican Spain in the 1930s passed laws banning the Jesuits on grounds that they were obedient to a power different from the state. Pope Pius XI wrote about this: "It was an expression of a soul deeply hostile to God and the Catholic religion, to have disbanded the Religious Orders that had taken a vow of obedience to an authority different from the legitimate authority of the State. In this way it was sought to do away with the Society of Jesus – which can well glory in being one of the soundest auxiliaries of the Chair of Peter – with the hope, perhaps, of then being able with less difficulty to overthrow in the near future, the Christian faith and morale in the heart of the Spanish nation, which gave to the Church of God the grand and glorious figure of Ignatius Loyola." [77]

Post–Vatican II

The 20th century witnessed both growth and decline. Following a trend within the Catholic priesthood at large, Jesuit numbers peaked in the 1950s and have declined steadily since. Meanwhile, the number of Jesuit institutions has grown considerably, due in large part to a post–Vatican II focus on the establishment of Jesuit secondary schools in inner-city areas and an increase in voluntary lay groups inspired in part by the Spiritual Exercises. Among the notable Jesuits of the 20th century, John Courtney Murray was called one of the "architects of the Second Vatican Council" and drafted what eventually became the Council's endorsement of religious freedom, Dignitatis Humanae Personae.

In Latin America, the Jesuits had significant influence in the development of liberation theology, a movement that was controversial in the Catholic community after the negative assessment of it by Pope John Paul II in 1984.[78]

Under Superior General Pedro Arrupe, social justice and the preferential option for the poor emerged as dominant themes of the work of the Jesuits. When Arrupe was paralyzed by a stroke in 1981, Pope John Paul II, not entirely pleased with the progressive turn of the Jesuits, took the unusual step of appointing the venerable and aged Paolo Dezza for an interim to oversee "the authentic renewal of the Church",[79] instead of the progressive American priest Vincent O'Keefe whom Arrupe had preferred.[80] In 1983 John Paul gave leave for the Jesuits to appoint a successor to Arrupe.

On 16 November 1989, six Jesuit priests (Ignacio Ellacuria, Segundo Montes, Ignacio Martin-Baro, Joaquin López y López, Juan Ramon Moreno, and Amado López), Elba Ramos their housekeeper, and Celia Marisela Ramos her daughter, were murdered by the Salvadoran military on the campus of the University of Central America in San Salvador, El Salvador, because they had been labeled as subversives by the government.[81] The assassinations galvanized the society's peace and justice movements, including annual protests at the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation at Fort Benning, Georgia, United States, where several of the assassins had been trained under US government sponsorship.[82]

On 21 February 2001, the Jesus priest Avery Dulles, an internationally known author, lecturer, and theologian, was created a Cardinal of the Catholic Church by Pope John Paul II. The son of former Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, Avery Dulles was long known for his carefully reasoned argumentation and fidelity to the teaching office of the church. An author of 22 books and over 700 theological articles, Dulles died on 12 December 2008 at Fordham University, where he taught for twenty years as the Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society. He was, at his passing, one of ten Jesuit cardinals in the Catholic Church.

In 2002, Boston College president and Jesuit priest William P. Leahy initiated the Church in the 21st Century program as a means of moving the church "from crisis to renewal". The initiative has provided the society with a platform for examining issues brought about by the worldwide Catholic sex abuse cases, including the priesthood, celibacy, sexuality, women's roles, and the role of the laity.[83]

In April 2005, Thomas J. Reese, editor of the American Jesuit weekly magazine America, resigned at the request of the society. The move was widely published in the media as the result of pressure from the Vatican, following years of criticism by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith on articles touching subjects such as HIV/AIDS, religious pluralism, homosexuality, and the right of life for the unborn. Following his resignation, Reese spent a year-long sabbatical at Santa Clara University before being named a fellow at the Woodstock Theological Center in Washington, D.C., and later Senior Analyst for the National Catholic Reporter. President Barack Obama appointed him to the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom in 2014 and again in 2016.[84]

On 2 February 2006, Peter Hans Kolvenbach informed members of the Society of Jesus that, with the consent of Pope Benedict XVI, he intended to step down as Superior General in 2008, the year he would turn 80.

On 22 April 2006, Feast of Our Lady, Mother of the Society of Jesus, Pope Benedict XVI greeted thousands of Jesuits on pilgrimage to Rome, and took the opportunity to thank God "for having granted to your Company the gift of men of extraordinary sanctity and of exceptional apostolic zeal such as St Ignatius of Loyola, St Francis Xavier, and Bl Peter Faber." He said "St Ignatius of Loyola was above all a man of God, who gave the first place of his life to God, to his greater glory and his greater service. He was a man of profound prayer, which found its center and its culmination in the daily Eucharistic Celebration."[85]

In May 2006, Benedict XVI also wrote a letter to Superior General Peter Hans Kolvenbach on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Pope Pius XII's encyclical Haurietis aquas, on devotion to the Sacred Heart, because the Jesuits have always been "extremely active in the promotion of this essential devotion."[86] In his 3 November 2006 visit to the Pontifical Gregorian University, Benedict XVI cited the university as "one of the greatest services that the Society of Jesus carries out for the universal Church".[87]

The 35th General Congregation of the Society of Jesus convened on 5 January 2008, and elected Adolfo Nicolás as the new Superior General on 19 January 2008. In a letter to the Fathers of the Congregation, Benedict XVI wrote:[88]

As my Predecessors have said to you on various occasions, the Church needs you, relies on you and continues to turn to you with trust, particularly to reach those physical and spiritual places which others do not reach or have difficulty in reaching. Paul VI's words remain engraved on your hearts: "Wherever in the Church, even in the most difficult and extreme fields, at the crossroads of ideologies, in the social trenches, there has been and there is confrontation between the burning exigencies of man and the perennial message of the Gospel, here also there have been, and there are, Jesuits" (Address to the 32nd General Congregation of the Jesuits, 3 December 1974; ORE, 12 December, n. 2, p. 4.)

In 2013, Jesuit Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio became Pope Francis. Before he became Pope, he was appointed bishop when he was in "virtual estrangement from the Jesuits" due to the complexities of Argentina in the 1980s while he was Jesuit Provincial Superior, trying to protect Jesuits but not approving of their participation in violent groups.[89][90][91] Once elected, there was an immediate reconciliation, and Pope Francis has been bringing the Jesuit simplicity, love for the poor, and service of the flock into the papacy.[89]

On 2 October 2016, General Congregation 36 convened in Rome, convoked by Superior General Adolfo Nicolás, who had announced his intention to resign at age 80.[92][93][94] On October 14, the 36th General Congregation of the Society of Jesus elected Arturo Sosa, a Venezuelan, as its thirty-first Superior General.[95]

Ignatian spirituality

The spirituality practiced by the Jesuits, called Ignatian spirituality, ultimately based on the Catholic faith and the gospels, is drawn from the Constitutions, The Letters, and Autobiography, and most specially from St. Ignatius' Spiritual Exercises, whose purpose is "to conquer oneself and to regulate one's life in such a way that no decision is made under the influence of any inordinate attachment." The Exercises culminate in a contemplation whereby one develops a facility to "find God in all things."

Formation

The formation (training) of Jesuits seeks to prepare men spiritually, academically, and practically for the ministries they will be called to offer the church and world. Saint Ignatius was strongly influenced by the Renaissance, and he wanted Jesuits to be able to offer whatever ministries were most needed at any given moment and, especially, to be ready to respond to missions (assignments) from the pope. Formation for priesthood normally takes between eight and fourteen years, depending on the man's background and previous education, and final vows are taken several years after that, making Jesuit formation among the longest of any of the religious orders.

Government of the society

The society is headed by a Superior General with the formal title Praepositus Generalis, Latin for "provost-general", more commonly called Father General or General. He is elected by the General Congregation for life or until he resigns; he is confirmed by the Pope and has absolute authority in running the society. The current Superior General of the Jesuits is the Venezuelan Arturo Sosa who was elected on 14 October 2016.[96]

The Father General is assisted by "assistants", four of whom are "assistants for provident care" and serve as general advisors and a sort of inner council, and several other regional assistants, each of whom heads an "assistancy", which is either a geographic area (for instance the North American Assistancy) or an area of ministry (for instance higher education). The assistants normally reside with Father General in Rome and along with others form an advisory council to the General. A vicar general and secretary of the society run day-to-day administration. The General is also required to have an admonitor, a confidential advisor whose task is to warn the General honestly and confidentially when he might be acting imprudently or contrary to the church's magisterium. The central staff of the General is known as the Curia.[96]

The society is divided into geographic provinces, each of which is headed by a Provincial Superior, generally called Father Provincial, chosen by the General. He has authority over all Jesuits and ministries in his area, and is assisted by a socius who acts as a sort of secretary and chief of staff. With the approval of the General, the provincial appoints a novice master and a master of tertians to oversee formation, and rectors of local communities of Jesuits.[97] For better cooperation and apostolic efficacy in each continent, the Jesuit provinces are grouped into six Jesuit Conferences worldwide.

Each Jesuit community within a province is normally headed by a rector who is assisted by a "minister", from the Latin for "servant", a priest who helps oversee the community's day-to-day needs.

The General Congregation is a meeting of all of the assistants, provincials, and additional representatives who are elected by the professed Jesuits of each province. It meets irregularly and rarely, normally to elect a new superior general and/or to take up some major policy issues for the Order. The General meets more regularly with smaller councils composed of just the provincials.

Habit and dress

Jesuits do not have an official habit. The society's Constitutions gives the following instructions: "The clothing too should have three characteristics: first, it should be proper; second, conformed to the usage of the country of residence; and third, not contradictory to the poverty we profess." (Const. 577)

Historically, a "Jesuit-style cassock" became "standard issue": it was wrapped around the body and was tied with a cincture, rather than the customary buttoned front. A tuftless biretta (only diocesan clergy wore tufts) and a ferraiolo (cape) completed the look. As such, though it was the common priestly dress of Ignatius' day, Jesuit garb appeared distinctive, and became identifiable over time. During the missionary periods of North America, the various native peoples referred to Jesuits as "Blackrobes" because of their black cassocks.

Today, most Jesuits in the United States wear the clerical collar and black clothing of ordinary priests, although some still wear the black cassock.[98] Jesuits in tropical countries may use a white cassock when ministering outdoors.

Controversies

Power-seeking

The Monita Secreta (Secret Instructions of the Jesuits), published in 1612 and in 1614 in Kraków, is alleged to have been written by Claudio Acquaviva, the fifth general of the society, but was probably written by former Jesuit Jerome Zahorowski. It purports to describe the methods to be adopted by Jesuits for the acquisition of greater power and influence for the society and for the Roman Catholic Church. The Catholic Encyclopedia states the book is a forgery, fabricated to ascribe a sinister reputation to the Society of Jesus.[99]

Political intrigue

The Jesuits were temporarily banished from France in 1594 after a man named Jean Châtel tried to assassinate the king of France, Henri IV. Under questioning, Châtel revealed that he had been educated by the Jesuits of the Collège de Clermont. The Jesuits were accused of inspiring Châtel's attack. Two of his former teachers were exiled and a third was hanged.[100] The Collège de Clermont was closed, and the building was confiscated. The Jesuits were banned from France, although this ban was quickly lifted.

In England, Henry Garnet, one of the leading English Jesuits, was hanged for misprision of treason because of his knowledge of the Gunpowder Plot (1605). The Plot was the attempted assassination of King James I of England and VI of Scotland, his family, and most of the Protestant aristocracy in a single attack, by exploding the Houses of Parliament. Another Jesuit, Oswald Tesimond, managed to escape arrest for his involvement in this plot.[101]

Casuistic justification

Jesuits have been accused of using casuistry to obtain justifications for unjustifiable actions (cf. formulary controversy and Lettres Provinciales, by Blaise Pascal).[102] Hence, the Concise Oxford Dictionary of the English language lists "equivocating" as a secondary denotation of the word "Jesuit". Modern critics of the Society of Jesus include Avro Manhattan, Alberto Rivera, and Malachi Martin, the latter being the author of The Jesuits: The Society of Jesus and the Betrayal of the Roman Catholic Church (1987).[103]

Anti-Semitism

Although in the first 30 years of the existence of the Society of Jesus there were many Jesuits who were conversos (Catholic-convert Jews), an anti-converso faction led to the Decree de genere (1593) which proclaimed that either Jewish or Muslim ancestry, no matter how distant, was an insurmountable impediment for admission to the Society of Jesus.[104] This new rule was contrary to the original wishes of Ignatius who "said that he would take it as a special grace from our Lord to come from Jewish lineage."[105] The 16th-century Decree de genere remained in exclusive force until it was repealed in 1946.[lower-alpha 2]

Theological debates

Within the Roman Catholic Church, there has existed a sometimes tense relationship between Jesuits and the Holy See due to questioning of official church teaching and papal directives, such as those on abortion,[108][109] birth control,[110][111][112][113] women deacons,[114] homosexuality, and liberation theology.[115][116] Usually, this theological free thinking is academically oriented, being prevalent at the university level. From this standpoint, the function of this debate is less to challenge the magisterium than to publicize the results of historical research or to illustrate the church's ability to compromise in a pluralist society based on shared values that do not always align with religious teachings.[117] This has not prevented Popes from appointing Jesuits to powerful positions in the church. John Paul II and Benedict XVI together appointed ten Jesuit Cardinals to notable jobs. Under Benedict, Archbishop Luis Ladaria Ferrer was Secretary of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and Federico Lombardi was Vatican Press Secretary.[118]

Nazi persecution

The Catholic Church faced persecution in Nazi Germany. Hitler was anticlerical and had particular disdain for the Jesuits. According to John Pollard, the Jesuit's "ethos represented the most intransigent opposition to the philosophy of Nazism",[119] and so the Nazis considered them as one of their most dangerous enemies. A Jesuit college in the city of Innsbruck served as a center for anti-Nazi resistance and was closed down by the Nazis in 1938.[120] Jesuits were a target for Gestapo persecution, and many Jesuit priests were deported to concentration camps.[121] Jesuits made up the largest contingent of clergy imprisoned in the Priest Barracks of Dachau Concentration Camp.[122] Lapomarda lists some 30 Jesuits as having died at Dachau.[123] Of the total of 152 Jesuits murdered by the Nazis across Europe, 43 died in the concentration camps and an additional 27 died from captivity or its results.[124]

The Superior General of Jesuits at the outbreak of war was Wlodzimierz Ledochowski, a Pole. The Nazi persecution of the Catholic Church in Poland was particularly severe. Vincent Lapomarda wrote that Ledochowski helped "stiffen the general attitude of the Jesuits against the Nazis" and that he permitted Vatican Radio to carry on its campaign against the Nazis in Poland. Vatican Radio was run by the Jesuit Filippo Soccorsi and spoke out against Nazi oppression, particularly with regard to Poland and to Vichy-French anti-Semitism.[125]

Several Jesuits were prominent in the small German Resistance.[127] Among the central membership of the Kreisau Circle of the Resistance were the Jesuit priests Augustin Rösch, Alfred Delp, and Lothar König.[128] The Bavarian Jesuit Provincial, Augustin Rosch, ended the war on death row for his role in the July Plot to overthrow Hitler. Another non-military German Resistance group, dubbed the "Frau Solf Tea Party" by the Gestapo, included the Jesuit priest Friedrich Erxleben.[129] The German Jesuit Robert Leiber acted as intermediary between Pius XII and the German Resistance.[130][131]

Among the Jesuit victims of the Nazis, Germany's Rupert Mayer has been beatified. Mayer was a Bavarian Jesuit who clashed with the Nazis as early as 1923. Continuing his critique following Hitler's rise to power, Mayer was imprisoned in 1939 and sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. As his health declined, the Nazis feared the creation of a martyr and sent him to the Abbey of Ettal in 1940. There he continued to give sermons and lectures against the evils of the Nazi régime, until his death in 1945.[132][133]

Rescue efforts during the Holocaust

In his history of the heroes of the Holocaust, the Jewish historian Martin Gilbert notes that in every country under German occupation, priests played a major part in rescuing Jews, and that the Jesuits were one of the Catholic Orders that hid Jewish children in monasteries and schools to protect them from the Nazis.[134][135] Fourteen Jesuit priests have been formally recognized by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem, for risking their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust of World War II: Roger Braun (1910–1981) of France;[136] Pierre Chaillet (1900–1972) of France;[137] Jean-Baptist De Coster (1896–1968) of Belgium;[138] Jean Fleury (1905–1982) of France;[139] Emile Gessler (1891–1958) of Belgium; Jean-Baptiste Janssens (1889–1964) of Belgium; Alphonse Lambrette (1884–1970) of Belgium; Emile Planckaert (1906–2006) of France; Jacob Raile (1894–1949) of Hungary; Henri Revol (1904–1992) of France; Adam Sztark (1907–1942) of Poland; Henri Van Oostayen (1906–1945) of Belgium; Ioannes Marangas (1901–1989) of Greece; and Raffaele de Chantuz Cubbe (1904–1983) of Italy. For more information on them see 100 Heroic Jesuits of the Second World War (2015) by Vincent A. Lapomarda.

Several other Jesuits are known to have rescued or given refuge to Jews during that period.[140] A plaque commemorating the 152 Jesuit priests who gave of their lives during the Holocaust was installed in April 2007 at the Jesuits' Rockhurst University in Kansas City, Missouri, United States.

In science

The Jesuits have made numerous significant contributions to the development of science. For example, the Jesuits have dedicated significant study to earthquakes, and seismology has been described as "the Jesuit science".[141] The Jesuits have been described as "the single most important contributor to experimental physics in the seventeenth century."[142] According to Jonathan Wright in his book God's Soldiers, by the eighteenth century the Jesuits had "contributed to the development of pendulum clocks, pantographs, barometers, reflecting telescopes and microscopes – to scientific fields as various as magnetism, optics and electricity. They observed, in some cases before anyone else, the colored bands on Jupiter's surface, the Andromeda nebula, and Saturn's rings. They theorized about the circulation of the blood (independently of Harvey), the theoretical possibility of flight, the way the moon affected the tides, and the wave-like nature of light."[143]

The Jesuit China missions of the 16th and 17th centuries introduced Western science and astronomy. One modern historian writes that in late Ming courts, the Jesuits were "regarded as impressive especially for their knowledge of astronomy, calendar-making, mathematics, hydraulics, and geography."[144] The Society of Jesus introduced, according to Thomas Woods, "a substantial body of scientific knowledge and a vast array of mental tools for understanding the physical universe, including the Euclidean geometry that made planetary motion comprehensible."[145] Another expert quoted by Woods said the scientific revolution brought by the Jesuits coincided with a time when science was at a very low level in China.

Notable members

Notable Jesuits include missionaries, educators, scientists, artists, philosophers, and Pope Francis. Among many distinguished early Jesuits was St. Francis Xavier, a missionary to Asia who converted more people to Catholicism than anyone before, and St. Robert Bellarmine, a doctor of the Church. José de Anchieta and Manuel da Nóbrega, founders of the city of São Paulo, Brazil, were Jesuit priests. Another famous Jesuit was St. Jean de Brebeuf, a French missionary who was martyred during the 17th century in what was once New France (now Ontario) in Canada.

In Spanish America, José de Acosta wrote a major work on early Peru and New Spain with important material on indigenous peoples. In South America, Saint Peter Claver was notable for his mission to African slaves, building on the work of Alonso de Sandoval. Francisco Javier Clavijero was expelled from New Spain during the Suppression of the Society of Jesus in 1767 and wrote an important history of Mexico during his exile in Italy. Eusebio Kino is renowned in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico (an area then called the Pimeria Alta). He founded numerous missions and served as the peace-bringer between the tribes and the government of New Spain. Antonio Ruiz de Montoya was an important missionary in the Jesuit reductions of Paraguay.

Baltasar Gracián was a 17th-century Spanish Jesuit and baroque prose writer and philosopher. He was born in Belmonte, near Calatayud (Aragon). His writings, particularly El Criticón (1651-7) and Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia ("The Art of Prudence", 1647) were lauded by Schopenhauer and Nietzsche.

In Scotland, St John Ogilive, a Jesuit, is the nation's only native saint.

There are notable Jesuits in the modern era, the most prominent being Pope Francis. Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio of Argentina was elected Pope Francis on 13 March 2013 and is the first Jesuit pope.[146]

Gerard Manley Hopkins was one of the first English poets to use sprung verse. Anthony de Mello was a Jesuit priest and psychotherapist who became widely known for his books which introduced Westerners to the East Indian traditions of spirituality.

The Feast of All Jesuit Saints and Blesseds is celebrated on November 5.[147]

Institutions

Educational institutions

Although the work of the Jesuits today embraces a wide variety of apostolates, ministries, and civil occupations, they are probably most well known for their educational work. Since the inception of the order, Jesuits have been teachers. Besides serving on the faculty of Catholic and secular schools, the Jesuits are the Catholic religious order with the second highest number of schools which they run: 168 tertiary institutions in 40 countries and 324 secondary schools in 55 countries. (The Brothers of the Christian Schools have over 560 Lasallian educational institutions.) They also run elementary schools at which they are less likely to teach. Many of the schools are named after St. Francis Xavier and other prominent Jesuits.

Jesuit educational institutions aim to promote the values of Eloquentia Perfecta. This is a Jesuit tradition that focuses on cultivating a person as a whole, as one learns to speak and write for the common good.

| Jesuit universities gallery | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Social and development institutions

Since the Second Vatican Council and their own General Congregations which followed it, Jesuits have become increasingly involved in works directed primarily toward social and economic development for the poor and marginalized.[148] Included in this would be research, training, advocacy, and action for human development, as well as direct services. Most Jesuit schools have an office that fosters social awareness and social service in the classroom and through extracurricular programs, usually detailed on their websites. The Jesuits also run over 500 notable or stand-alone social or economic development centres in 56 countries around the world.

Since the Second Vatican Council, Jesuits have founded many schools with the special purpose of serving the poor or marginalized, as among the Dalits in India and the Cristo Rey Network in the United States.

Publications

Jesuits are also known for their involvement in publications. La Civiltà Cattolica, a periodical produced in Rome by the Jesuits, has often been used as a semi-official platform for popes and Vatican officials to float ideas for discussion or hint at future statements or positions. In the United States, America magazine has long had a prominent place in Catholic intellectual circles. Most Jesuit colleges and universities have their own presses which produce a variety of books, book series, textbooks, and academic publications. Ignatius Press, founded by a Jesuit, is an independent publisher of Catholic books, most of which are of the popular academic or lay-intellectual variety.

In Australia, the Jesuits produce a number of magazines, including Eureka Street, Madonna, Australian Catholics, and Province Express.

In Sweden the Catholic cultural magazine Signum, edited by the Newman Institute, covers a broad spectrum of issues concerning faith, culture, research, and society. The printed version of Signum is published eight times per year. In addition, there is an up-to-date website (www.signum.se) containing an article archive dating from 1975 to the present.

In popular culture

- The character Father Mulcahy in the novel, movie, and TV show M*A*S*H franchise is a Jesuit priest.

- The character Damien Karras from the book and movie The Exorcist is a Jesuit priest.

- The 1986 British drama film The Mission revolves around the experiences of a Jesuit missionary in 18th century South America.

- In The Body (2001 film), Antonio Banderas plays a Jesuit priest.

- In Deliver Us from Evil (2014 film) Édgar Ramírez plays a Jesuit priest.

- The Martin Scorsese film Silence is based on two Jesuit priests who travel to Japan to spread Christianity.

- The main protagonist in James Blish's 1958 novel A Case of Conscience is a Jesuit priest.

- Aramis, one of the main characters of A. Dumas' 1844 novel The Three Musketeers, is made Superior General of the Jesuits in The Man in the Iron Mask (1850).

- Mary Doria Russell's 1996 novel The Sparrow follows a Jesuit space mission to make first contact with a new-found planet; the majority of characters are Jesuits.

See also

- Apostleship of Prayer

- Bollandist

- Canadian Indian residential school system

- Jesuit conspiracy theories

- Jesuit Ivy

- Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos

- Jesuits and Nazi Germany

- List of Jesuit buildings

- List of saints of the Society of Jesus

- Misiones Province

- Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu

- Roman Catholicism in China

- Roman Catholicism in Japan

- Sexual abuse scandal in the Society of Jesus

Notes

- ↑ Spanish: "todo el que quiera militar para Dios".[3]

- ↑ Jesuit scholar John Padberg states that the restriction on Jewish/Muslim converts was limited only to the degree of parentage. Fourteen years later this was extended back to the fifth degree. Over time the restriction relating to Muslim ancestry was dropped.[106] In 1923, the 27th Jesuit General Congregation specified that "The impediment of origin extends to all who are descended from the Jewish race, unless it is clear that their father, grandfather, and great grandfather have belonged to the Catholic Church." In 1946, the 29th General Congregation dropped the requirement but still called for "cautions to be exercised before admitting a candidate about whom there is some doubt as to the character of his hereditary background." Robert Aleksander Maryks interprets the 1593 "Decree de genere" as preventing, despite Ignatius' desires, any Jewish or Muslim conversos and, by extension, any person with Jewish or Muslim ancestry, no matter how distant, from admission to the Society of Jesus.[107]

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 Cheney, David M. (13 April 2017). "Society of Jesus (Institute of Consecrated Life)". Catholic-Hierarchy. Kansas City. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ↑ Spiteri, Stephen C. (2016). Baroque Routes. University of Malta. p. 16.

- ↑ (in Spanish) See Fórmula del Instituto on Google Books.

- ↑ O'Malley 2006, p. xxxv.

- ↑ "Poverty And Chastity For Every Occasion". National Public Radio. Washington, D.C. 5 March 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Jesuits: 'God's marines'". The Week. New York. 23 March 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ↑ "About Our Jesuits". Ignatius House Retreat Center. Atlanta, Georgia. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ "News on the elections of the new Superior General". Sjweb.info. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "africa.reuters.com, Spaniard becomes Jesuits' new "black pope"". Africa.reuters.com. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "Curia Generalizia of the Society of Jesus". Sjweb.info. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- 1 2 Curia Generalis, Society of Jesus (10 April 2013). "From the Curia - THE SOCIETY OF JESUS IN NUMBERS". Digital News Service SJ. The Jesuit Portal – Society of Jesus Homepage. 17 (10). Retrieved 27 June 2013.

The new statistics of the Society of Jesus as of January 1st, 2013 have been published. [...] As of 1 January 2013, the total number of Jesuits was 17,287 [...]—a net loss of 337 members from 1 January 2012.

- ↑ See perspective circle graph (3D pie chart) on Google Images.

- ↑ Lapitan, Giselle (22 May 2012). "The changing face of the Jesuits". Province Express. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ↑ Gray, Mark M. (9 January 2015). "Nineteen Sixty-four: By the Numbers: Jesuit Demography". nineteensixty-four.blogspot.com. CARA (Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate). Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ↑ Raper, Mark (23 May 2012). "Changing to best serve the universal mission". Jesuit Asia Pacific Conference. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ↑ Reilly, Patrick (28 July 2016). "American Jesuits Are in a Free Fall, and the Crisis is Getting Worse". National Catholic Register. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- 1 2 Puca, Pasquale (30 January 2008). "St. Ignatius of Loyola and the Development of the Society of Jesus". L'Osservatore Romano Weekly Edition in English. The Cathedral Foundation: 12. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- ↑ "St. Aloysius College mission statement". Staloysius.nsw.edu.au. Retrieved 2013-03-18.

- ↑ "Time Magazine on "Men for Others"". America Magazine. 2009-11-10. Retrieved 2017-05-30.

- 1 2 Text of the Formula of the Institute as approved by Pope Paul III in 1540, Boston College, Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies.

- ↑ O'Malley 1993, p. 5.