Jefferson Davis

| Jefferson Davis | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of the Confederate States | |

|

In office February 22, 1862 – May 10, 1865 Provisional: February 18, 1861 – February 22, 1862 | |

| Vice President | Alexander H. Stephens |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| United States Senator from Mississippi | |

|

In office March 4, 1857 – January 21, 1861 | |

| Preceded by | Stephen Adams |

| Succeeded by |

Adelbert Ames (Vacant until 1870) |

|

In office August 10, 1847 – September 23, 1851 | |

| Preceded by | Jesse Speight |

| Succeeded by | John J. McRae |

| 23rd United States Secretary of War | |

|

In office March 7, 1853 – March 4, 1857 | |

| President | Franklin Pierce |

| Preceded by | Charles M. Conrad |

| Succeeded by | John B. Floyd |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Mississippi's At-large district | |

|

In office December 8, 1845 – June 1, 1846 | |

| Preceded by | Tilghman Tucker |

| Succeeded by | Henry T. Ellett |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Jefferson Finis Davis June 3, 1808 Fairview, Kentucky |

| Died |

December 6, 1889 (aged 81) New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Resting place |

Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) |

Sarah Knox Taylor (m. 1835; her death 1835) Varina Howell (m. 1845; his death 1889) |

| Alma mater |

Transylvania University United States Military Academy |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch |

United States Army United States Volunteers |

| Years of service | 1825–1835; 1846–1847 |

| Rank |

First Lieutenant Colonel |

| Unit | First Dragoons |

| Commands | First Mississippi |

| Battles/wars | |

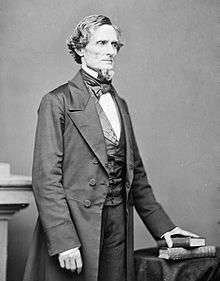

Jefferson Finis Davis[1] (June 3, 1808 – December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the President of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He was a member of the Democratic Party who represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives prior to becoming president of the Confederacy. He was the 23rd United States Secretary of War, serving under U.S. President Franklin Pierce from 1853 to 1857.

Davis was born in Fairview, Kentucky, to a moderately prosperous farmer, and grew up on his older brother Joseph's large cotton plantations in Mississippi and Louisiana. Joseph Davis also secured his appointment to the United States Military Academy. After graduating, Jefferson Davis served six years as a lieutenant in the United States Army. He fought in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848), as the colonel of a volunteer regiment. Before American Civil War, he operated a large cotton plantation in Mississippi and owned as many as 74 slaves.[2] Although he argued against secession in 1858,[3] he believed states had an unquestionable right to leave the Union.

Davis's first wife, Sarah Knox Taylor, died of malaria after three months of marriage, and he also struggled with recurring bouts of the disease.[4] He was unhealthy for much of his life. At the age of 36, Davis married again, to 18-year-old Varina Howell, a native of Natchez who had been educated in Philadelphia and had some family ties in the North. They had six children. Only two survived him, and only one married and had children.

Many historians attribute the Confederacy's weaknesses to the poor leadership of Davis.[5] His preoccupation with detail, reluctance to delegate responsibility, lack of popular appeal, feuds with powerful state governors and generals, favoritism toward old friends, inability to get along with people who disagreed with him, neglect of civil matters in favor of military ones, and resistance to public opinion all worked against him.[6][7] Historians agree he was a much less effective war leader than his Union counterpart Abraham Lincoln. After Davis was captured in 1865, he was accused of treason and imprisoned at Fort Monroe. He was never tried and was released after two years. While not disgraced, Davis had been displaced in ex-Confederate affection after the war by his leading general, Robert E. Lee. Davis wrote a memoir entitled The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, which he completed in 1881. By the late 1880s, he began to encourage reconciliation, telling Southerners to be loyal to the Union. Ex-Confederates came to appreciate his role in the war, seeing him as a Southern patriot, and he became a hero of the Lost Cause in the post-Reconstruction South.[8]

Early life and first military career

Davis's paternal grandparents each immigrated separately to North America from the region of Snowdonia in North Wales in the early 18th century. The rest of his ancestry was English. After arriving in Philadelphia, Davis's paternal grandfather Evan settled in the colony of Georgia, which was developed chiefly along the coast. He married the widow Lydia Emory Williams, who had two sons from a previous marriage.

Their son Samuel Emory Davis was born in 1756. He served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, along with his two older half-brothers. In 1783, after the war, he married Jane Cook. She was born in 1759 to William Cook and his wife Sarah Simpson in what is now Christian County, Kentucky. In 1793, the Samuel Davis family relocated to Kentucky, establishing what is now the community of Fairview on the border of Christian and Todd counties. Samuel and Jane Davis had ten children; Joseph was the oldest son, born in 1784; Jefferson was the last and was born on June 3, 1807 or 1808, on the Davis homestead in Fairview.[9] The year of his birth is uncertain; Davis gave both 1807 and 1808, at different points in his life.[10] Samuel had been a young man when Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Jefferson was the third President of the United States, and Samuel, admiring him greatly, named his last son after the president.[11] Coincidentally, Abraham Lincoln was born eight months later, less than 100 miles (160 km) to the northeast in Hodgenville, Kentucky. In the early 20th century, the Jefferson Davis State Historic Site was established near the site of Davis's birth.[12]

During Davis's youth, his family moved twice: in 1811 to St. Mary Parish, Louisiana, and less than a year later to Wilkinson County, Mississippi. The international slave trade was prohibited in 1808, and planters used the domestic slave trade to procure laborers for developing cotton culture in the Deep South. Three of Davis's older brothers served in the War of 1812. In 1813, Davis began his education at the Wilkinson Academy in the small town of Woodville, near the family cotton plantation.

His brother Joseph, who was 24 years older, acted as a surrogate father and encouraged Jefferson in his education. Two years later, Davis entered the Catholic school of Saint Thomas at St. Rose Priory, a school operated by the Dominican Order in Washington County, Kentucky. At the time, he was the only Protestant student at the school. In 1818 Davis returned to Mississippi, studying at Jefferson College at Washington. Three years later in 1821, he returned to Kentucky, where he studied at Transylvania University in Lexington. (At the time, these colleges were like academies, roughly equivalent to high schools.)[13] His father Samuel died on July 4, 1824, when Jefferson was 16 years old.[14]

Joseph arranged for Davis to get an appointment and attend the United States Military Academy (West Point) starting in late 1824.[15] While there, he was placed under house arrest for his role in the Eggnog Riot during Christmas 1826. Cadets smuggled whiskey into the academy to make eggnog, and more than one-third of the cadets were involved in the incident. In June 1828, Davis graduated 23rd in a class of 33.[16]

Following graduation, Second Lieutenant Davis was assigned to the 1st Infantry Regiment and was stationed at Fort Crawford, Prairie du Chien, Michigan Territory. Zachary Taylor, a future president of the United States, had assumed command shortly before Davis arrived in early 1829. In March 1832, Davis returned to Mississippi on furlough, having had no leave since he first arrived at Fort Crawford. He was still in Mississippi during the Black Hawk War but returned to the fort in August. At the conclusion of the war, Colonel Taylor assigned him to escort Black Hawk to prison. Davis made an effort to shield Black Hawk from curiosity seekers, and the chief noted in his autobiography that Davis treated him "with much kindness" and showed empathy for the leader's situation as a prisoner.[17]

First marriage and early career

Davis fell in love with Sarah Knox Taylor, daughter of his commanding officer, future president Zachary Taylor. Both Sarah and Davis sought Taylor's permission to marry. Taylor refused, as he did not wish his daughter to have the difficult life of a military wife on frontier army posts.[18] Davis's own experience led him to appreciate Taylor's objection. He consulted with his older brother Joseph, and they both began to question the value of an Army career. Davis hesitated to leave, but his desire for Sarah overcame this, and he resigned his commission in a letter dated April 20, 1835.[19] He had arranged for the letter to be sent to the War Department for him on May 12 when he did not return from leave;[20] he had made no mention to Taylor of his intention to resign.[21] Against his former commander's wishes, on June 17, he married Sarah in Louisville, Kentucky. His resignation became effective June 30.[22]

Davis's older brother Joseph had been very successful and owned Hurricane Plantation and 1,800 acres (730 ha)[23] of adjoining land along the Mississippi River on a peninsula 20 miles south of Vicksburg, Mississippi. The adjoining land was known as Brierfield since it was largely covered with brush and briers. Wanting to have his youngest brother and his wife nearby, Joseph gave use of Brierfield to Jefferson, who eventually developed Brierfield Plantation there. Joseph retained the title.[24]

In August 1835, Jefferson and Sarah traveled south to his sister Anna's home in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana; the plantation was known as Locust Grove. Their goal was to spend the hot summer months in the countryside away from the river floodplain, for their health, but both of them contracted either malaria or yellow fever.[4] Sarah died at the age of 21 on September 15, 1835, after just three months of marriage.[25][26] Davis was also severely ill,[25] and his family feared for his life. In the month following Sarah's death, he slowly improved, although he remained weak.[27]

In late 1835, Davis sailed from New Orleans to Havana, Cuba, to help restore his health. He was accompanied by James Pemberton, his only slave at that time.[28] Davis observed the Spanish military and sketched fortifications. Although no evidence points to his having any motive beyond general interest, the authorities knew that Davis was a former army officer and warned him to stop his observations. Bored and feeling somewhat better, Davis booked passage on a ship to New York, then continued to Washington, D.C., where he visited his old schoolmate George Wallace Jones. He soon returned with Pemberton to Mississippi.[29]

For several years following Sarah's death, Davis was reclusive and honored her memory. He spent time clearing Brierfield and developing his plantation, studied government and history, and had private political discussions with his brother Joseph.[30] By early 1836, Davis had purchased 16 slaves; he held 40 slaves by 1840, and 74 by 1845. Davis promoted Pemberton to be overseer of the field teams. In 1860, he owned 113 slaves.[31]

In 1840, Davis first became involved in politics when he attended a Democratic Party meeting in Vicksburg and, to his surprise, was chosen as a delegate to the party's state convention in Jackson. In 1842, he attended the Democratic convention, and, in 1843, became a Democratic candidate for the state House of Representatives from the Warren County-Vicksburg district; he lost his first election.[32] In 1844, Davis was sent to the party convention for a third time, and his interest in politics deepened. He was selected as one of six presidential electors for the 1844 presidential election and campaigned effectively throughout Mississippi for the Democratic candidate James K. Polk.[33]

Second marriage and family

In 1844, Davis met Varina Banks Howell, then 17 years old, whom his brother Joseph had invited for the Christmas season at Hurricane Plantation. She was a granddaughter of New Jersey Governor Richard Howell; her mother's family was from the South and included successful Scots-Irish planters. Within a month of their meeting, the 35-year-old widower Davis had asked Varina to marry him, and they became engaged despite her parents' initial concerns about his age and politics. They were married on February 26, 1845.[34]

During this time, Davis was persuaded to become a candidate for the United States House of Representatives and began canvassing for the election. In early October 1845 he traveled to Woodville to give a speech. He arrived a day early to visit his mother there, only to find that she had died the day before. After the funeral, he rode the 40 miles (64 km) back to Natchez to deliver the news, then returned to Woodville again to deliver his speech. He won the election.[35]

Jefferson and Varina had six children; three died before reaching adulthood. Samuel Emory, born July 30, 1852, was named after his grandfather; he died June 30, 1854, of an undiagnosed disease.[36] Margaret Howell was born February 25, 1855,[37] and was the only child to marry and raise a family. She married Joel Addison Hayes, Jr. (1848–1919), and they had five children.[38] They were married in St. Lazarus Church, nicknamed "The Confederate Officers' Church", in Memphis, Tennessee.[39][40] In the late 19th century, they moved from Memphis to Colorado Springs, Colorado. She died on July 18, 1909, at the age of 54.[41]

Jefferson Davis, Jr., was born January 16, 1857. He died of yellow fever at age 21 on October 16, 1878, during an epidemic in the Mississippi River Valley that caused 20,000 deaths.[42] Joseph Evan, born on April 18, 1859, died at the age of five due to an accidental fall on April 30, 1864.[43] William Howell, born on December 6, 1861, was named for Varina's father; he died of diphtheria at age 10 on October 16, 1872.[44] Varina Anne, known as "Winnie", was born on June 27, 1864, several months after her brother Joseph's death. She was known as the Daughter of the Confederacy as she was born during the war. After her parents refused to let her marry into a northern abolitionist family, she never married.[45] She died nine years after her father, on September 18, 1898, at age 34.[46][47]

Davis had poor health for most of his life, including repeated bouts of malaria, battle wounds from fighting in the Mexican–American War and a chronic eye infection that made bright light painful. He also had trigeminal neuralgia, a nerve disorder that causes severe pain in the face; it has been called one of the most painful known ailments.[40][48]

Mexican–American War

In 1846 the Mexican–American War began. Davis resigned his House seat in early June and raised a volunteer regiment, the 155th Infantry Regiment, becoming its colonel under the command of his former father-in-law, General Zachary Taylor.[49] On July 21 the regiment sailed from New Orleans for Texas. Colonel Davis sought to arm his regiment with the M1841 Mississippi rifle. At this time, smoothbore muskets were still the primary infantry weapon, and any unit with rifles was considered special and designated as such. President James K. Polk had promised Davis the weapons if he would remain in Congress long enough for an important vote on the Walker tariff. General Winfield Scott objected on the basis that the weapons were insufficiently tested. Davis insisted and called in his promise from Polk, and his regiment was armed with the rifles, making it particularly effective in combat.[50] The regiment became known as the Mississippi Rifles because it was the first to be fully armed with these new weapons.[51] The incident was the start of a lifelong feud between Davis and Scott.[52]

In September, Davis participated in the Battle of Monterrey, during which he led a successful charge on the La Teneria fort.[53] On February 22, 1847, Davis fought bravely at the Battle of Buena Vista and was shot in the foot, being carried to safety by Robert H. Chilton. In recognition of Davis's bravery and initiative, Taylor is reputed to have said, "My daughter, sir, was a better judge of men than I was."[15] On May 17, President Polk offered Davis a federal commission as a brigadier general and command of a brigade of militia. Davis declined the appointment, arguing that the Constitution gives the power of appointing militia officers to the states, not the federal government.[54]

Return to politics

Senator

Honoring Davis's war service, Governor Brown of Mississippi appointed him to the vacant position of United States Senator Jesse Speight, who had died on May 1, 1847. Davis took his temporary seat on December 5, and in January 1848 he was elected by the state legislature to serve the remaining two years of the term.[55] In December, during the 30th United States Congress, Davis was made a regent of the Smithsonian Institution and began serving on the Committee on Military Affairs and the Library Committee.[56]

In 1848, Senator Davis proposed and introduced an amendment (the first of several) to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that would have annexed most of northeastern Mexico, but it failed on a vote of 11 to 44.[57] Southerners wanted to increase territory held in Mexico as an area for the expansion of slavery. Regarding Cuba, Davis declared that it "must be ours" to "increase the number of slaveholding constituencies."[58] He also was concerned about the security implications of a Spanish holding lying relatively close to the coast of Florida.[59]

A group of Cuban revolutionaries led by Venezuelan adventurer Narciso López intended to liberate Cuba from Spanish rule by the sword. Searching for a military leader for a filibuster expedition, they first offered command of the Cuban forces to General William J. Worth, but he died before making his decision.[60] In the summer of 1849, López visited Davis and asked him to lead the expedition. He offered an immediate payment of $100,000 (worth more than $2,000,000 in 2013[61]), plus the same amount when Cuba was liberated. Davis turned down the offer, stating that it was inconsistent with his duty as a senator. When asked to recommend someone else, Davis suggested Robert E. Lee, then an army major in Baltimore; López approached Lee, who also declined on the grounds of his duty.[62][63]

The Senate made Davis chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs on December 3, 1849, during the first session of the 31st United States Congress. On December 29 he was elected to a full six-year term (by the Mississippi legislature, as the constitution mandated at the time). Davis had not served a year when he resigned (in September 1851) to run for the governorship of Mississippi on the issue of the Compromise of 1850, which he opposed. He was defeated by fellow Senator Henry Stuart Foote by 999 votes.[64] Left without political office, Davis continued his political activity. He took part in a convention on states' rights, held at Jackson, Mississippi, in January 1852. In the weeks leading up to the presidential election of 1852, he campaigned in numerous Southern states for Democratic candidates Franklin Pierce and William R. King.[65]

Secretary of War

Franklin Pierce won the presidential election, and in 1853 made Davis his Secretary of War.[66] In this capacity, Davis began the Pacific Railroad Surveys in order to determine various possible routes for the proposed Transcontinental Railroad. He promoted the Gadsden Purchase of today's southern Arizona from Mexico, partly because it would provide an easier southern route for the new railroad; the Pierce administration agreed, and the land was purchased in December 1853.[67] He saw the size of the regular army as insufficient to fulfill its mission, and maintained that salaries would have to be increased, something which had not occurred for 25 years. Congress agreed and increased the pay scale, and added four regiments which increased the army's size from about 11,000 to about 15,000.[68] Davis also introduced general usage of the rifles that he had used successfully during the Mexican–American War.[69] As a result, both the morale and capability of the army was improved. He became involved in public works when Pierce gave him responsibility for construction of the Washington Aqueduct and an expansion of the U.S. Capitol, both of which he managed closely.[70] The Pierce administration ended in 1857 after Pierce's loss of the Democratic nomination to James Buchanan. Davis's term was to end with Pierce's, so he ran for the Senate, was elected, and re-entered it on March 4, 1857.[71]

Return to Senate

In the 1840s, tensions were growing between the North and South over various issues including slavery. The Wilmot Proviso, introduced in 1846, contributed to these tensions; if passed, it would have banned slavery in any land acquired from Mexico. The Compromise of 1850 brought a temporary respite, but the Dred Scott case, decided by the United States Supreme Court in 1857, spurred public debate. Chief Justice Roger Taney ruled that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional and that African Americans had no standing as citizens under the constitution. Northerners were outraged and there was increasing talk in the South of secession from the Union.[72]

Davis's renewed service in the Senate was interrupted in early 1858 by an illness that began as a severe cold and which threatened him with the loss of his left eye. He was forced to remain in a darkened room for four weeks.[73] He spent the summer of 1858 in Portland, Maine. On the Fourth of July, Davis delivered an anti-secessionist speech on board a ship near Boston. He again urged the preservation of the Union on October 11 in Faneuil Hall, Boston, and returned to the Senate soon after.[74]

As he explained in his memoir The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, Davis believed that each state was sovereign and had an unquestionable right to secede from the Union. At the same time, he counseled delay among his fellow Southerners, because he did not think that the North would permit the peaceable exercise of the right to secession. Having served as secretary of war under President Pierce, he also knew that the South lacked the military and naval resources necessary for defense in a war. Following the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, however, events accelerated. South Carolina adopted an ordinance of secession on December 20, 1860, and Mississippi did so on January 9, 1861. Davis had expected this but waited until he received official notification. On January 21, the day Davis called "the saddest day of my life",[75] he delivered a farewell address to the United States Senate, resigned and returned to Mississippi.[76]

President of the Confederate States of America

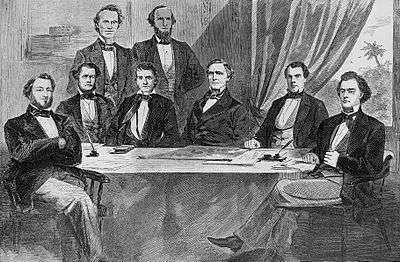

Anticipating a call for his services since Mississippi had seceded, Davis had sent a telegraph message to Governor John J. Pettus saying, "Judge what Mississippi requires of me and place me accordingly."[77] On January 23, 1861, Pettus made Davis a major general of the Army of Mississippi.[15] On February 9, a constitutional convention met at Montgomery, Alabama and considered Davis and Robert Toombs of Georgia as a possible president. Davis, who had widespread support from six of the seven states, easily won. He was seen as the "champion of a slave society and embodied the values of the planter class," and was elected provisional Confederate President by acclamation.[78][79] He was inaugurated on February 18, 1861.[80][81] Alexander H. Stephens was chosen as Vice President, but he and Davis feuded constantly.[82]

Davis was the first choice because of his strong political and military credentials. He wanted to serve as commander in chief of the Confederate armies but said he would serve wherever directed.[83] His wife Varina Davis later wrote that when he received word that he had been chosen as president, "Reading that telegram he looked so grieved that I feared some evil had befallen our family."[84]

Several forts in Confederate territory remained in Union hands. Davis sent a commission to Washington with an offer to pay for any federal property on Southern soil, as well as the Southern portion of the national debt, but Lincoln refused to meet with the commissioners. Brief informal discussions did take place with Secretary of State William Seward through Supreme Court Justice John A. Campbell. From Alabama, he later resigned from the federal government. Seward hinted that Fort Sumter would be evacuated, but gave no assurance.[85]

On March 1, 1861, Davis appointed General P. G. T. Beauregard to command all Confederate troops in the vicinity of Charleston, South Carolina, where state officials prepared to take possession of Fort Sumter. Beauregard was to prepare his forces but await orders to attack the fort. Within the fort the issue was not of the niceties of geo-political posturing but of survival. They would be out of food on the 15th. The small union crew had but half a dozen officers under Major Anderson. Famously this included the baseball folk hero Abner Doubleday. More improbable yet was a Union officer who had the name of Jefferson C. Davis. He would spend the war being taunted for his name but not his loyalty to the Northern cause. The newly installed President Lincoln, not wishing to initiate hostilities, informed South Carolina Governor Pickens that he was dispatching a small fleet of ships from the navy yard in New York to resupply but not re-enforce Fort Pickens in Florida and Fort Sumter. The US President did not inform CSA President Davis of this intended resupply of food and fuel. Jefferson Davis, for Lincoln, was the leader of an insurrection and so without legal standing in US affairs. To deal with him would be to give legitimacy to the rebellion. Holding to the belief that Sumter was the property of the sovereign United States was the reason for maintaining the garrison on the island fortress. He informed Gov. Pickens that the resupply mission would not land troops or munitions unless they were fired upon. As it turned out, just as the supply ships approached Charleston harbor, the bombardment would begin and the flotilla watched the spectacle from 10 miles at sea.

Davis faced the most important decision of his career: to prevent reinforcement at Fort Sumter or to let it take place. He and his cabinet decided to demand that the Federal garrison surrender and, if this was refused, to use military force to prevent reinforcement before the fleet arrived. Major Anderson did not surrender. With Jefferson Davis's endorsement, Beauregard began the bombarding of the fort in the early dawn of April 12. The Confederates continued their artillery attack on Fort Sumter until it surrendered on April 14. No one was killed in the artillery duel, but the attack on the U.S. fortress meant the fighting had started. President Lincoln called up state militia to march south to recapture Federal property. In the North and South, massive rallies were held to demand immediate war. The Civil War had begun.[86][87][88][89]

When Virginia joined the Confederacy, Davis moved his government to Richmond in May 1861. He and his family took up his residence there at the White House of the Confederacy later that month.[90] Having served since February as the provisional president, Davis was elected to a full six-year term on November 6, 1861 and was inaugurated on February 22, 1862.[91]

At the start of the war, nearly 21 million people lived in the North compared to 9 million in the South. While the North's population was almost entirely white, the South had an enormous number of black slaves and people of color. While the latter were free, becoming a soldier was seen as the prerogative of white men only. Many Southerners were terrified at the idea of a black man with a gun. Excluding old men and boys, the white males available for Confederate service were less than two million. There was also the additional burden that the near four million black slaves had to be heavily policed as there was no trust between the owner and "owned". The North had vastly greater industrial capacity, built nearly all of the locomotives, steamships, and industrial machinery and had a much larger and more integrated railroad system. Nearly all of the munitions facilities were in the North, while critical ingredients for gunpowder were in very short supply in the South.

Much of the railroad track that existed in the Confederacy was of simple rail-way design just meant to carry the large bales of cotton to local river ports in the harvest season. These often did not connect to other rail-lines making internal shipments of goods difficult at best. While the Union had a large navy, the new Confederate Navy had only a few captured warships or newly built vessels. These did surprisingly well but ultimately were sunk or abandoned as the Union Navy controlled more rivers and ports. Rebel 'raiders' loosed on the Northern ships on the Atlantic did tremendous damage and sent Yankee ships into safe harbors as insurance rates soared. The Union blockade of the South, however, made imports via blockade runners difficult and expensive. Somewhat awkwardly, these runners didn't bring significant amounts of the war materials so greatly needed but rather the European luxuries sought as a relief from the privations of the war-time's stark conditions.[92][93]

In June 1862, Davis was forced to assign General Robert E. Lee to replace the wounded Joseph E. Johnston in command of the Army of Northern Virginia, the main Confederate army in the Eastern Theater. This turned out to be a great development for the CSA as Lee proved to be a brilliant war commander. That December Davis made a tour of Confederate armies in the west of the country. Davis had a very small circle of military advisers. He largely made the main strategic decisions on his own, though he had special respect for Lee's views. Given the Confederacy's limited resources compared with the Union, Davis decided that the Confederacy would have to fight mostly on the strategic defensive. He maintained this outlook throughout the war, paying special attention to the defense of his national capital at Richmond. He approved Lee's strategic offensives when he felt that military success would both shake Northern self-confidence and strengthen the peace movements there. However, the several campaigns invading the North were met with defeat. A bloody battle at Antietam in Maryland as well as the ride into Kentucky, the Confederate Heartland Offensive (both in 1862)[94] drained irreplaceable men and talented officers. A final offense led to the three day blood-letting at Gettysburg in Pennsylvania (1863),[95] crippling the South still further. The status of techniques and munitions made the defensive side much more likely to endure: an expensive lesson vindicating Davis's initial belief.

Administration and cabinet

As provisional president in 1861, Davis formed his first cabinet. Robert Toombs of Georgia was the first Secretary of State and Christopher Memminger of South Carolina became Secretary of the Treasury. LeRoy Pope Walker of Alabama was made Secretary of War, after being recommended for this post by Clement Clay and William Yancey (both of whom declined to accept cabinet positions themselves). John Reagan of Texas became Postmaster General. Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana became Attorney General. Although Stephen Mallory was not put forward by the delegation from his state of Florida, Davis insisted that he was the best man for the job of Secretary of the Navy, and he was eventually confirmed.[96]

Since the Confederacy was founded, among other things, on states' rights, one important factor in Davis's choice of cabinet members was representation from the various states. He depended partly upon recommendations from congressmen and other prominent people. This helped maintain good relations between the executive and legislative branches. This also led to complaints as more states joined the Confederacy, however, because there were more states than cabinet positions.[97]

As the war progressed, this dissatisfaction increased and there were frequent changes to the cabinet. Toombs, who had wished to be president himself, was frustrated as an advisor and resigned within a few months of his appointment to join the army. Robert Hunter of Virginia replaced him as Secretary of State on July 25, 1861.[98] On September 17, Walker resigned as Secretary of War due to a conflict with Davis, who had questioned his management of the War Department and had suggested he consider a different position. Walker requested, and was given, command of the troops in Alabama. Benjamin left the Attorney General position to replace him, and Thomas Bragg of North Carolina (brother of General Braxton Bragg) took Benjamin's place as Attorney General.[99]

Following the November 1861 election, Davis announced the permanent cabinet in March 1862. Benjamin moved again, to Secretary of State. George W. Randolph of Virginia had been made the Secretary of War. Mallory continued as Secretary of the Navy and Reagan as Postmaster General. Both kept their positions throughout the war. Memminger remained Secretary of the Treasury, while Thomas Hill Watts of Alabama was made Attorney General.[100]

In 1862 Randolph resigned from the War Department, and James Seddon of Virginia was appointed to replace him. In late 1863, Watts resigned as Attorney General to take office as the Governor of Alabama, and George Davis of North Carolina took his place. In 1864, Memminger withdrew from the Treasury post due to congressional opposition, and was replaced by George Trenholm of South Carolina. In 1865, congressional opposition likewise caused Seddon to withdraw, and he was replaced by John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky.[101]

Cotton was the South's primary export and the basis of its economy, and the system of production the South used was dependent upon slave labor. At the outset of the Civil War, Davis realized that intervention from European powers would be vital if the Confederacy was to stand against the Union. The administration sent repeated delegations to European nations, but several factors prevented Southern success in terms of foreign diplomacy. The Union blockade of the Confederacy led European powers to remain neutral, contrary to the Southern belief that a blockade would cut off the supply of cotton to Britain and other European nations and prompt them to intervene on behalf of the South. Many European countries objected to slavery. Britain had abolished it in the 1830s, and Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 made support for the South even less appealing in Europe. Finally, as the war progressed and the South's military prospects dwindled, foreign powers were not convinced that the Confederacy had the strength to become independent. In the end, not a single foreign nation recognized the Confederate States of America.[102]

Strategic failures

Most historians sharply criticize Davis for his flawed military strategy, his selection of friends for military commands, and his neglect of homefront crises.[103][104] Until late in the war, he resisted efforts to appoint a general-in-chief, essentially handling those duties himself. On January 31, 1865, Lee assumed this role, but it was far too late. Davis insisted on a strategy of trying to defend all Southern territory with ostensibly equal effort. This diluted the limited resources of the South and made it vulnerable to coordinated strategic thrusts by the Union into the vital Western Theater (e.g., the capture of New Orleans in early 1862). He made other controversial strategic choices, such as allowing Lee to invade the North in 1862 and 1863 while the Western armies were under very heavy pressure. When Lee lost at Gettysburg, Vicksburg simultaneously fell, and the Union took control of the Mississippi River, splitting the Confederacy. At Vicksburg, the failure to coordinate multiple forces on both sides of the Mississippi River rested primarily on Davis's inability to create a harmonious departmental arrangement or to force such generals as Edmund Kirby Smith, Earl Van Dorn, and Theophilus H. Holmes to work together.[105]

Davis has been faulted for poor coordination and management of his generals. This includes his reluctance to resolve a dispute between Leonidas Polk, a personal friend, and Braxton Bragg, who was defeated in important battles and distrusted by his subordinates.[106] He was similarly reluctant to relieve the capable but overcautious Joseph E. Johnston until, after numerous frustrations which he detailed in a March 1, 1865 letter to Col. James Phelan of Mississippi, he replaced him with John Bell Hood.[107][108]

Davis gave speeches to soldiers and politicians but largely ignored the common people, who came to resent the favoritism shown the rich and powerful; Davis thus failed to harness Confederate nationalism.[109] One historian speaks of "the heavy-handed intervention of the Confederate government." Economic intervention, regulation, and state control of manpower, production and transport were much greater in the Confederacy than in the Union.[110] Davis did not use his presidential pulpit to rally the people with stirring rhetoric; he called instead for people to be fatalistic and to die for their new country.[111] Apart from two month-long trips across the country where he met a few hundred people, Davis stayed in Richmond where few people saw him; newspapers had limited circulation, and most Confederates had little favorable information about him.[112]

To finance the war, the Confederate government initially issued bonds, but investment from the public never met the demands. Taxes were lower than in the Union and collected with less efficiency; European investment was also insufficient. As the war proceeded, both the Confederate government and the individual states printed more and more paper money. Inflation increased from 60% in 1861 to 300% in 1863 and 600% in 1864. Davis did not seem to grasp the enormity of the problem.[113][114]

In April 1863, food shortages led to rioting in Richmond, as poor people robbed and looted numerous stores for food until Davis cracked down and restored order.[115] Davis feuded bitterly with his vice president. Perhaps even more seriously, he clashed with powerful state governors who used states' rights arguments to withhold their militia units from national service and otherwise blocked mobilization plans.[116]

Davis is widely evaluated as a less effective war leader than Lincoln, even though Davis had extensive military experience and Lincoln had little. Davis would have preferred to be an army general and tended to manage military matters himself. Lincoln and Davis led in very different ways. According to one historian,

Lincoln was flexible; Davis was rigid. Lincoln wanted to win; Davis wanted to be right. Lincoln had a broad strategic vision of Union goals; Davis could never enlarge his narrow view. Lincoln searched for the right general, then let him fight the war; Davis continuously played favorites and interfered unduly with his generals, even with Robert E. Lee. Lincoln led his nation; Davis failed to rally the South.— William J. Cooper, Jr.

There were many factors that led to Union victory over the Confederacy, and Davis recognized from the start that the South was at a distinct disadvantage; but in the end, Lincoln helped to achieve victory, whereas Davis contributed to defeat.[117]

Final days of the Confederacy

In March 1865, General Order 14 provided for enlisting slaves into the army, with a promise of freedom for service. The idea had been suggested years earlier, but Davis did not act upon it until late in the war, and very few slaves were enlisted.[118]

On April 3, with Union troops under Ulysses S. Grant poised to capture Richmond, Davis escaped to Danville, Virginia, together with the Confederate Cabinet, leaving on the Richmond and Danville Railroad. Lincoln sat in Davis' Richmond office just 40 hours later. William T. Sutherlin turned over his mansion, which served as Davis's temporary residence from April 3 to April 10, 1865.[119] On about April 12, Davis received Robert E. Lee's letter announcing surrender.[120] He issued his last official proclamation as president of the Confederacy, and then went south to Greensboro, North Carolina.[121]

After Lee's surrender, a public meeting was held in Shreveport, Louisiana, at which many speakers supported continuation of the war. Plans were developed for the Davis government to flee to Havana, Cuba. There, the leaders would regroup and head to the Confederate-controlled Trans-Mississippi area by way of the Rio Grande.[122] None of these plans was put into practice.

On April 14, Lincoln was shot, dying the next day. Davis expressed regret at his death. He later said that he believed Lincoln would have been less harsh with the South than his successor, Andrew Johnson.[123] In the aftermath, Johnson issued a $100,000 reward for the capture of Davis and accused him of helping to plan the assassination. As the Confederate military structure fell into disarray, the search for Davis by Union forces intensified.[124]

President Davis met with his Confederate Cabinet for the last time on May 5, 1865, in Washington, Georgia, and officially dissolved the Confederate government. The meeting took place at the Heard house, the Georgia Branch Bank Building, with 14 officials present. Along with their hand-picked escort led by Given Campbell, Davis and his wife Varina Davis were captured by Union forces on May 10 at Irwinville in Irwin County, Georgia.[125]

Mrs. Davis recounted the circumstances of her husband's capture as described below: "Just before day the enemy charged our camp yelling like demons...I pleaded with him to let me throw over him a large waterproof wrap which had often served him in sickness during the summer season for a dressing gown and which I hoped might so cover his person that in the grey of the morning he would not be recognized. As he strode off I threw over his head a little black shawl which was around my own shoulders, saying that he could not find his hat and after he started sent my colored woman after him with a bucket for water hoping that he would pass unobserved."[126]:172

It was reported in the media that Davis put his wife's overcoat over his shoulders while fleeing. This led to the persistent rumor that he attempted to flee in women's clothes, inspiring caricatures that portrayed him as such.[127] Over 40 years later, an article in the Washington Herald claimed that Mrs. Davis's heavy shawl had been placed on him to protect him from the "chilly atmosphere of the early hour of the morning" by the slave James Henry Jones, Davis's valet who served Davis and his family during and after the Civil War.[128] Meanwhile, Davis's belongings continued on the train bound for Cedar Key, Florida. They were first hidden at Senator David Levy Yulee's plantation in Florida, then placed in the care of a railroad agent in Waldo. On June 15, 1865, Union soldiers seized Davis's personal baggage from the agent, together with some of the Confederate government's records. A historical marker was erected at this site.[129][130][131] In 1939, Jefferson Davis Memorial Historic Site was opened to mark the place where Confederate President Jefferson Davis was captured.

Imprisonment

On May 19, 1865, Davis was imprisoned in a casemate at Fortress Monroe on the coast of Virginia. Irons were riveted to his ankles at the order of General Nelson Miles who was in charge of the fort. Davis was allowed no visitors, and no books except the Bible. He became sicker, and the attending physician warned that his life was in danger, but this treatment continued for some months until late autumn when he was finally given better quarters. General Miles was transferred in mid-1866, and Davis's treatment continued to improve.[132]

Pope Pius IX (see Pope Pius IX and the United States), seeing himself a prisoner in the Vatican, after learning that Davis was a prisoner, sent him a portrait inscribed with the Latin words "Venite ad me omnes qui laboratis, et ego reficiam vos, dicit Dominus", which correspond to Matthew 11:28,[133][134] "Come to me, all you that labor, and are burdened, and I will refresh you, sayeth the Lord". A hand-woven crown of thorns associated with the portrait is often said to have been made by the Pope[135][136] but may have been woven by Davis's wife Varina.[137]

Varina and their young daughter Winnie were allowed to join Davis, and the family was eventually given an apartment in the officers' quarters. Davis was indicted for treason while imprisoned; one of his attorneys was ex-Governor Thomas Pratt of Maryland.[138] There was a great deal of discussion in 1865 about bringing treason trials, especially against Jefferson Davis, and there was no consensus in President Johnson's cabinet to do so. Although Davis wanted such a trial for himself, there were no treason trials against anyone, as it was felt they would probably not succeed and would impede reconciliation. There was also a concern at the time that such action could result in a judicial decision that would validate the constitutionality of secession (later removed by the Supreme Court ruling in Texas v. White (1869) declaring secession unconstitutional).[139][140][141][142]

.jpg)

A jury of 12 African American and 12 Anglo American men was recruited by United States Circuit Court judge John Curtiss Underwood in preparation for the trial.[143]

After two years of imprisonment, Davis was released on bail of $100,000, which was posted by prominent citizens including Horace Greeley, Cornelius Vanderbilt and Gerrit Smith.[144] (Smith was a former member of the Secret Six who had supported abolitionist John Brown.) Davis went to Montreal, Canada to join his family which had fled there earlier, and lived in Lennoxville, Quebec until 1868[145] also visiting Cuba, and Europe in search of work.[146] At one stage he stayed as a guest of James Smith, a foundry owner in Glasgow, who had struck up a friendship with Davis when he toured the Southern States promoting his foundry business.[147] Davis remained under indictment until Andrew Johnson issued on Christmas Day of 1868 a presidential "pardon and amnesty" for the offense of treason to "every person who directly or indirectly participated in the late insurrection or rebellion" and after a federal circuit court on February 15, 1869, dismissed the case against Davis after the government's attorney informed the court that he would no longer continue to prosecute Davis.[139][140][141]

Later years

In 1869, Davis became president of the Carolina Life Insurance Company in Memphis, Tennessee, where he resided at the Peabody Hotel. Upon General Lee's death in 1870, Davis presided over the memorial meeting in Richmond. Elected to the U.S. Senate again, he was refused the office in 1875, having been barred from federal office by Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. He turned down the opportunity to become the first president of the Agriculture and Mechanical College of Texas (now Texas A&M University).[148]

During Reconstruction, Davis publicly remained silent on his opinions; but privately he expressed opinions that federal military rule and Republican authority over former Confederate states was unjustified. He considered "Yankee and Negroe" rule in the South oppressive. Like most of his white contemporaries, Davis held the belief that blacks were inferior to whites.[149] The historian William J. Cooper has stated that Davis believed in a Southern social order that included "a democratic white polity based firmly on dominance of a controlled and excluded black caste."[150]

Ownership of the Brierfield plantation was embroiled in court cases, with the politics of the state judges playing a key role. Only after the Democrats took control of the state supreme court in 1881 did Davis, for the first time in his life, gain legal title.[151]

In 1876, Davis promoted a society for the stimulation of US trade with South America. He visited England the next year. In 1877, Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey, a wealthy widow who had heard of his difficulties, invited him to stay at her estate and plantation house of "Beauvoir" on the Gulf Coast (facing the Gulf of Mexico) in Biloxi, Mississippi. She provided him with a cabin for his own use and helped him with his writing through organization, dictation, editing, and encouragement. Knowing she was severely ill, in 1878 Dorsey made over her will, leaving Beauvoir and her financial assets of $50,000 (equivalent to $1,227,000 in 2014) to Jefferson Davis and, in the case of his death, to his only surviving child, Winnie Davis.[152][153] Dorsey died in 1879, by which time both the Davises and Winnie were living at Beauvoir. Over the next two years, Davis completed The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government (1881).[154]

Davis's reputation among ex-Confederates was restored by the book and by his warm reception on his tour of the region in 1886 and 1887. In numerous stops, he attended Lost Cause ceremonies, where large crowds showered him with affection and local leaders presented emotional speeches honoring his sacrifices to the would-be nation. Such events helped the South come to terms with their defeat and continued for decades after the war.[155] The Meriden Daily Journal stated that Davis, at a reception held in New Orleans in May 1887, urged southerners to be loyal to the nation. He said, "United you are now, and if the Union is ever to be broken, let the other side break it." Davis stated that men in the Confederacy had successfully fought for their own rights with inferior numbers during the Civil War and that the northern historians ignored this view.[156] Davis firmly believed that Confederate secession was constitutional. The former Confederate president was optimistic concerning American prosperity and the next generation.[157]

Davis completed A Short History of the Confederate States of America in October 1889. On November 6, he left Beauvoir to visit his plantation at Brierfield. While in New Orleans, he was caught in a sleety rain, and on the steamboat trip upriver, he had a severe cold; on November 13 he left Brierfield to return to New Orleans. Varina Davis, who had taken another boat to Brierfield, met him on the river, and he finally received some medical care; two doctors came aboard further south and found he had acute bronchitis complicated by malaria.[158] They arrived in New Orleans three days later, and he was taken to the home of Charles Erasmus Fenner, an Associate Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court. Davis remained in bed but was stable for the next two weeks; however, he took a turn for the worse in early December. Just when he appeared to be improving, he lost consciousness on the evening of December 5 and died at 12:45 a.m. on Friday, December 6, 1889, in the presence of several friends and with his hand in Varina's.[159][160]

His funeral was one of the largest in the South. Davis was first entombed at the Army of Northern Virginia tomb at Metairie Cemetery in New Orleans. In 1893, Mrs. Davis decided to have his remains reinterred at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond.[161] After the remains were exhumed in New Orleans, they lay for a day at Memorial Hall of the newly organized Louisiana Historical Association, with many mourners passing by the casket, including Governor Murphy J. Foster, Sr. The body was placed on a Louisville and Nashville Railroad car and transported to Richmond, Virginia.[162] A continuous cortège, day and night, accompanied his body from New Orleans to Richmond.[163] He is interred at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond.[164]

Legacy

Jefferson Davis served in many roles. As a soldier, he was brave and resourceful.[53] As a politician, he served as a United States senator and a Mississippi congressman and was active and accomplished, although he never completed a full term in any elected position. As a plantation owner, he employed slave labor as did most of his peers in the South, and supported slavery.[24] As president of the Confederate States of America, he is widely viewed as an ineffective wartime leader; although the task of defending the Confederacy against the much stronger Union would have been a great challenge for any leader, Davis's performance in this role is considered poor.[117] After the war, he contributed to reconciliation of the South with the North, but remained a symbol for Southern pride.[8]

Some portions of his legacy were created not as memorials, but as contemporary recognition of his service at the time.

Fort Davis National Historic Site began as a frontier military post in October 1854, in the mountains of western Texas. It was named after then-United States Secretary of War Jefferson Davis. That fort gave its name to the surrounding Davis Mountains range, and the town of Fort Davis. The surrounding area was designated Jeff Davis County in 1887, with the town of Fort Davis as the county seat. Other states containing a Jefferson (or Jeff) Davis County/Parish include Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

Jefferson Davis Hospital, began operations in 1924 and was the first centralized municipal hospital to treat indigent patients in Houston, Texas.[165] The building was designated as a protected historic landmark on November 13, 2013, by the Houston City Council and is monitored by the Historic Preservation Office of the City of Houston Department of Planning and Development.[166] The hospital was named for Jefferson Davis, former president of the Confederacy, in honor of the Confederate soldiers who had been buried in the cemetery and as a means to console the families of the deceased.[167]

Numerous memorials to Jefferson Davis were created. The largest is the 351-foot (107 m) concrete obelisk located at the Jefferson Davis State Historic Site in Fairview, marking his birthplace. Construction of the monument began in 1917 and finished in 1924 at a cost of about $200,000.[12]

In 1913, the United Daughters of the Confederacy conceived the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway, a transcontinental highway to be built through the South.[168][169] Portions of the highway's route in Virginia, Alabama and other states still bear the name of Jefferson Davis.[168]

5-cent CSA

1970 issue

Davis appeared on several postage stamps issued by the Confederacy, including its first postage stamp (issued in 1861). In 1995, his portrait appeared on a United States postage stamp, part of a series of 20 stamps commemorating the 130th anniversary of end of the Civil War.[170][171] Davis was also celebrated on the 6-cent Stone Mountain Memorial Carving commemorative on September 19, 1970, at Stone Mountain, Georgia. The stamp portrayed Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson on horseback. It depicts a replica of the actual memorial, carved into the side of Stone Mountain at 400 feet (120 m) above ground level, the largest high-relief sculpture in the world.[172]

The Jefferson Davis Presidential Library was established at Beauvoir in 1998. For some years, the white-columned Biloxi mansion that was Davis's final home had served as a Confederate Veterans Home. The house and library were damaged by Hurricane Katrina in 2005; the house reopened in 2008.[173] Bertram Hayes-Davis, Davis's great-great grandson, is the executive director of Beauvoir, which is owned by the Mississippi Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.[174]

Based at Rice University in Houston, Texas, The Papers of Jefferson Davis is an editing project to publish documents related to Davis. Since the early 1960s, it has published 13 volumes, the first in 1971 and the most recent in 2012; two more volumes are planned. The project has roughly 100,000 documents in its archives.[175]

The birthday of Jefferson Davis is commemorated in several states. His actual birthday, June 3, is celebrated in Florida,[176] Kentucky,[177] Louisiana[178] and Tennessee;[179] in Alabama, it is celebrated on the first Monday in June.[180] In Mississippi, the last Monday of May (Memorial Day) is celebrated as "National Memorial Day and Jefferson Davis's Birthday".[181] In Texas, "Confederate Heroes Day" is celebrated on January 19, the birthday of Robert E. Lee;[179] Jefferson Davis's birthday had been officially celebrated on June 3 but was combined with Lee's birthday in 1973.[182]

Robert E. Lee's United States citizenship was posthumously restored in 1975. Jefferson Davis had been specifically excluded from earlier resolutions restoring rights to other Confederate officials, and a movement arose to restore Davis's citizenship as well. This was accomplished with the passing of Senate Joint Resolution 16 on October 17, 1978. In signing the law, President Jimmy Carter referred to this as the last act of reconciliation in the Civil War.[183]

Controversies

Several memorials to Davis have become contentious in recent years. In some instances, such controversies have resulted in the renaming, relocation or removal of a memorial.

Texas

In May 2015, the student government at the University of Texas at Austin voted almost unanimously to remove a statue of Jefferson Davis that had been erected on the campus South Mall.[184][185] Beginning shortly after the Charleston church shooting of 2015[186] "black lives matter" had been written repeatedly in bold red letters on the base of the Davis statue. Previous messages had included "Davis must fall" and "Liberate U.T."[187]

The University of Texas officials convened a task force to determine whether to honor the students' petition for removal of the statue. Acting on the strong recommendation of the task force, UT's President Gregory Fenves announced on August 13, 2015 that the statue would be relocated to serve as an educational exhibit in the university's Dolph Briscoe Center for American History museum.[188] The statue was removed on August 30, 2015.[189]

Virginia

In the former Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, the Museum of the Confederacy was involved in a controversy regarding a statue of Davis donated by the Sons of Confederate Veterans in 2008. Likewise, a statue of Abraham Lincoln, donated to the Civil War Visitor Center in Richmond in 2003, resulted in protests.[190]

In 2011, the County Board of Arlington County, Virginia, voted to change the name of Old Jefferson Davis Highway, the original route of Jefferson Davis Highway in the county, after the board's chairman made disparaging remarks about Davis. However, the name of Jefferson Davis Highway itself, a portion of U.S. 1 that only the Virginia General Assembly could rename, remained unchanged.[191]

In its 2016 legislative package, the Arlington County Board asked the Virginia General Assembly to rename the portion of Jefferson Davis Highway (U.S. 1) that was within the county.[192] However, no member of Arlington's legislative delegation offered any such legislation during the 2016 session of the General Assembly.[193]

In February 2016, the Virginia Attorney General's office issued an advisory opinion that the City of Alexandria, unlike the neighboring Arlington County, had the legal authority to change the name of the portion of Jefferson Davis Highway that was within the city's jurisdiction.[194] In September 2016, the Alexandria City Council voted unanimously to change the name of the city's portion of the highway.[195]

Washington

In 1998, officials of the city of Vancouver, Washington, removed a marker of the Jefferson Davis Highway (Washington State Route 99) and placed it in a cemetery shed in an action that several years later became controversial.[196] The marker was subsequently moved twice, and eventually was placed alongside Interstate 5 on private land purchased for the purpose of giving the marker a permanent home.[197][198]

In 2002, the Washington House of Representatives unanimously approved a bill (proposed by Hans Dunshee who also led the renaming effort in subsequent years)[199] that would have removed Davis' name from the road. However, a committee of the state's Senate subsequently killed the proposal.[200][201]

In March 2016, the Washington State Legislature unanimously passed a joint memorial that asked the state's transportation commission to designate the road as the "William P. Stewart Memorial Highway" to honor an African-American volunteer during the Civil War who later became a pioneer of the town and city of Snohomish.[202] In May 2016, the transportation commission agreed to rename the road.[199][203]

Louisiana

In New Orleans, there was a larger-than-life statue at the corner of Jeff Davis Parkway and Canal Street. By decision of the New Orleans City Council in December 2015, the statue was removed in the early morning hours of May 11, 2017.[204]

See also

- List of memorials to Jefferson Davis

- List of people from Kentucky

- List of people pardoned or granted clemency by the President of the United States

- List of slave owners

- List of United States Military Academy alumni

- List of United States Senators from Mississippi

Notes

- ↑ Davis 1996, p. 6, states: "Thus it was with a touch of humor, leavened by wishful thinking, that the boy born to her on June 3, 1808, found himself endowed with the middle name Finis, testimony to his father's familiarity with Latin and both parents' hope that this baby would be their last." However, Cooper 2000, p. 10, writes: "His parents also gave him a middle name, which by early manhood he dropped completely; only the initial F. survived."; and again Cooper 2000, p. 711n1, writes: "Some have also questioned whether Davis ever had a middle name. He used the initial at West Point, as did his mother in her will. Again, I assume that both would not have invented it... No evidence supports Hudson Strode's claim that the actual middle name was Finis, signaling the final child."

- ↑ Johnson, Paul (1997). A History of the American People. New York, New York: HarperCollins. p. 452. ISBN 0-06-016836-6.

- ↑ "The Anti-Secessionist Jefferson Davis". National Park Service. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- 1 2 Cooper 2000, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Cooper 2008, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Wiley, Bell I. (January 1967). "Jefferson Davis: An Appraisal". Civil War Times Illustrated. 6 (1): 4–17.

- ↑ Escott 1978, pp. 197, 256–274.

- 1 2 Strawbridge, Wilm K. (December 2007). "A Monument Better Than Marble: Jefferson Davis and the New South". Journal of Mississippi History. 69 (4): 325–347.

- ↑ Rennick, Robert M. (1987). Kentucky Place Names. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 97–98. ISBN 0813126312.

- ↑ Davis 1996, p. 709.

- ↑ Strode 1955, p. 3.

- 1 2 "Jefferson Davis State Historic Site". Kentucky State Parks. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

- ↑ Strode, 1955, pp. 11–27.

- ↑ Strode 1955, pp. 4–5.

- 1 2 3 Hamilton, Holman (1978). "Jefferson Davis Before His Presidency". The Three Kentucky Presidents. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813102467.

- ↑ U.S. Military Academy, Register of Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy from March 16 to January 1, 1850. Compiled by Capt. George W. Cullum. West Point, N.Y.: 1850, p. 148.

- ↑ Strode 1955, p. 76. Cooper 2000, pp. 53–55.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 65.

- ↑ Strode 1955, pp. 86–94.

- ↑ Davis 1996, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Davis 1996, p. 69.

- ↑ Davis 1996, pp. 69, 72.

- ↑ Strode 1955, p. 94.

- 1 2 Cooper 2000, pp. 81–83, 616.

- 1 2 Davis 1996, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ "Sarah Knox Taylor Davis 1814–1835, Wife of Jefferson Davis". LA cemeteries. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- ↑ Davis 1996, p. 75.

- ↑ Davis 1996, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Davis 1996, p. 76. Strode 1955, p. 108–109.

- ↑ Strode 1955, pp. 105, 109–11.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 75–79, 229. Davis 1996, p. 89.

- ↑ Strode 1955, pp. 121–123.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 84–88, 98–100.

- ↑ Strode 1955, pp. 125, 136.

- ↑ Strode 1955, pp. 140–141.

- ↑ Strode 1955, pp. 242, 268.

- ↑ Strode 1955, p. 273.

- ↑ "Margaret Howell Davis Hayes". The Papers of Jefferson Davis. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ↑ Harkins, John E. (December 25, 2009). "Memphis". The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Tennessee Historical Society. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- 1 2 Allen 1999, pp. 197–198.

- ↑ "Margaret Howell Davis Hayes Chapter No. 2652". Colorado United Daughters of the Confederacy. Retrieved 2011-07-20.

- ↑ Strode 1964, p. 436.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 480.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 595.

- ↑ Strode 1964, pp. 527–528.

- ↑ "Varina Anne Davis". The Papers of Jefferson Davis. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ↑ "Varina Howell Davis". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ↑ Potter, Robert (1994). Jefferson Davis: Confederate President. Steck-Vaughn Company. p. 74.

- ↑ Strode 1955, p. 157.

- ↑ Allen 1999, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Strode 1955, pp. 157–162.

- ↑ Taylor, John M. (1997). While Cannons Roared. Brasseys Inc. p. 2.

- 1 2 Strode 1955, pp. 164–167.

- ↑ Strode 1955, p. 188.

- ↑ Dodd 1907, pp. 12, 93. Cooper 2000, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Strode 1955, p. 195.

- ↑ Rives, George Lockhart (1913). The United States and Mexico, 1821–1848. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 634–636.

- ↑ McPherson 1989, p. 104.

- ↑ Strode 1955, p. 210.

- ↑ Strode 1955, p. 211.

- ↑ Williamson, Samuel H. (2011). Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1774 to present. MeasuringWorth

- ↑ Thomson, Janice E. (1996). Mercenaries, Pirates and Sovereigns. Princeton University Press. p. 121.

- ↑ Strode 1955, pp. 211–212.

- ↑ Rowland, Dunbar (1912). The Official and Statistical Register of the State of Mississippi. Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Nashville, Tennessee: Press of Brandon Printing Company. p. 111. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ↑ Dodd 1907, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Kleber, John E., ed. (1992). "Davis, Jefferson". The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813117720.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 257.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 251.

- ↑ Dodd 1907, pp. 80, 133–135.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 259.

- ↑ Dodd 1907, pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Dodd 1909, pp. 122–129.

- ↑ Allen 1999, p. 232.

- ↑ Dodd 1907, pp. 12, 171–172.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 3.

- ↑ "Jefferson Davis' Farewell". United States Senate. Retrieved 2011-06-09.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 322.

- ↑ Cashin, Joan E. (2006). First Lady of the Confederacy: Varina Davis' Civil War. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Coulter 1950, p. 25.

- ↑ Strode 1955, pp. 402–403.

- ↑ "Inaugural Address of President Davis". Montgomery, Alabama: Shorter and Reid, Printers. February 18, 1861. Retrieved 2011-07-17.

- ↑ Dodd 1907, p. 221.

- ↑ Coulter 1950, p. 24.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 352.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 361–362.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 337–340.

- ↑ Donald, David Herbert (1995). Lincoln. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 285–299.

- ↑ Strode 1959, pp. 24–66.

- ↑ McPherson 1989, pp. 273–275.

- ↑ Strode 1959, pp. 90–94.

- ↑ Dodd 1907, p. 263.

- ↑ McPherson 1989, pp. 313–319.

- ↑ McPherson, James M. (2012). War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861–1865. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807835883.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 401–402.

- ↑ Dawson, Joseph G. III (April 2009). "Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy's "Offensive-Defensive" Strategy in the U.S. Civil War". Journal of Military History. 73 (2): 591–607. doi:10.1353/jmh.0.0262.

- ↑ Patrick 1944, p. 51.

- ↑ Patrick 1944, pp. 49–50, 56.

- ↑ Patrick 1944, pp. 53, 89.

- ↑ Patrick 1944, p. 53, 116–117.

- ↑ Patrick 1944, pp. 55–57.

- ↑ Patrick 1944, p. 57.

- ↑ "Preventing Diplomatic Recognition of the Confederacy, 1861–1865". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- ↑ Beringer, Richard E., Hattaway, Herman, Jones, Archer, and Still, William N., Jr. (1986). Why the South Lost the Civil War. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- ↑ Woodworth 1990, p. 309.

- ↑ Woodworth, Steven E. (1990). "Dismembering the Confederacy: Jefferson Davis and the Trans-Mississippi West". Military History of the Southwest. 20 (1): 1–22.

- ↑ Woodworth 1990, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Hattaway and Beringer 2002, pp. 338–344.

- ↑ Jefferson Davis to Col. James Phelan, March 1, 1865, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office,1895), Vol. 47, pt. 2, pp. 1303–1312.

- ↑ Escott 1978, pp. 269–270.

- ↑ Barney, William L. (2011). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Civil War. Oxford University Press. p. 341. ISBN 9780199782017.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 475, 496.

- ↑ Andrews, J. Cutler (1966). "The Confederate Press and Public Morale". Journal of Southern History. 32 (4): 445. JSTOR 2204925. doi:10.2307/2204925.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 351–352.

- ↑ Escott 1978, pp. 146, 269.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 447, 480, 496.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 511.

- 1 2 Cooper, Jr., William J. (2010), "A Reassessment of Jefferson Davis as War Leader", in Hewitt, Lawrence Lee; Bergeron, Jr., Arthur W., Confederate Generals in the Western Theater, Volume 1: Classic Essays on America's Civil War, Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, p. 161, ISBN 9781572337008

- ↑ "General Orders No. 14". Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1855–865. Kansas City: The Kansas City Public Library. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

[I]t does not extend freedom to the slaves who serve, giving them little personal motivation to support the Southern cause. Ultimately, very few blacks serve in the Confederate armed forces, as compared to hundreds of thousands who serve for the Union.

- ↑ Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff (June 1969). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Danville Public Library" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- ↑ Keegan, John (2009). The American Civil War: A Military History. Vintage Books. pp. 375–376. ISBN 9780307273147.

- ↑ Dodd 1907, pp. 353–357.

- ↑ Winters, John D. (1963). The Civil War in Louisiana. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 419. ISBN 9780807117255.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 528–529.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 533.

- ↑ "Jefferson Davis Was Captured". USA.gov. 2007. Retrieved 2010-02-04.

- ↑ From Varina Banks Howell Davis to Francis Preston Blair, Savannah, Ga., June 6, 1865. In Blair, Gist. Annals of Silver Spring, Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., Vol. 21 (1918), pp. 155–185.

- ↑ "Capture of Jefferson Davis". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2011-06-08.

- ↑ "People of Note. Davis' Old Servant," The Washington Herald, 4 November 1906: 6, col. 5.

- ↑ Boone, Floyd E. (1988). Florida Historical Markers & Sites: A Guide to More Than 700 Historic Sites. Houston, Texas: Gulf Publishing Company. p. 15. ISBN 9780872015586.

- ↑ "Historical Markers in Alachua County, Florida — DICKISON AND HIS MEN / JEFFERSON Davis' BAGGAGE". Alachua County Historical Commission. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-04.

- ↑ "Historic Markers Across Florida — Dickison and his men / Jefferson Davis' baggage". Latitude 34 North. Retrieved 2011-08-04.

- ↑ Dodd 1907, pp. 366–368.

- ↑ TR Media: Sir Charles Coulombe, America 1861–1865, with Stephen Heiner, 2011 on YouTube (5:45–10:00). Retrieved: 27 March 2014.

- ↑ "Pope Pius IX and the Confederacy". The Catholic Knight. 2 February 2009. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- ↑ Strode 1964, p. 302.

- ↑ Kelly, Brian (30 October 2008). "Blessed Pius IX and Jefferson Davis". Catholicism.org. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- ↑ Levin, Kevin (27 September 2009). "Update on Jefferson Davis's Crown of Thorns". Civil War Memory. Retrieved 2011-08-21.

- ↑ Blackford, Charles M. The Trials and Trial of Jefferson Davis. Vol. XXIX, in Southern Historical Society, edited by R. A. Brock, 45–81. Richmond, VA: William Ellis Jones, 1901, p. 62.

- 1 2 Nichols, Roy Franklin (1926). "United States vs. Jefferson Davis, 1865–1869". American Historical Review. 31 (2): 266–284. JSTOR 1838262.

- 1 2 Blight, David W. (2009). Race and Reunion. Harvard University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780674022096.

- 1 2 (1) Deutsch, Eberhard P. (February 1966). "United States v. Jefferson Davis: Constitutional Issues in the Trial for Treason". American Bar Association Journal. American Bar Association. 52 (2): 139–145. ISSN 0747-0088. JSTOR 25723506. OCLC 725827455. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

(2) Deutsch, Eberhard P. (March 1966). "United States v. Jefferson Davis: Constitutional Issues in the Trial for Treason". American Bar Association Journal. American Bar Association. 52 (3): 263–268. ISSN 0747-0088. JSTOR 25723552. OCLC 725827455. Retrieved 15 September 2016. - ↑ (1) Jefferson Davis (2008). The Papers of Jefferson Davis: June 1865-December 1870. Louisiana State UP. p. 96.

(2) Kennedy, James R; Kennedy, Walter Donald (1998). Was Jefferson Davis Right?. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing Co. p. 104. ISBN 156554370X. OCLC 39256326. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

(3) Texas v. White. Wikisource.

Texas v. White. Wikisource. - ↑ Watts, Jennifer A. (10 April 2017). "The Power of Touch". Huntington Library. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ↑ Strode 1955, p. 305.

- ↑ Hopper, Tristin (2014-07-25). "Freshly defeated in the U.S. Civil War, Confederate leader Jefferson Davis came to Canada to give the newly founded country defence tips". National Post. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 568–584.

- ↑ "Picture of former President on Scots visit found". The Herald. Glasgow, Scotland. 3 September 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ↑ Strode 1964, pp. 402–404.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 702.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 574–575, 602–603.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 675–676.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 676–678.

- ↑ Wyatt-Brown, Bertram (1994). The House of Percy: Honor, Melancholy and Imagination in a Southern Family. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Strode 1964, pp. 439–441, 448–449.

- ↑ Wilson, Charles Reagan (2009). Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865–1920. University of Georgia Press. pp. 18–24. ISBN 9780820340722.

- ↑ "Jefferson Davis' Loyalty". The Meriden Daily Journal. May 14, 1887. p. 1.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 658.

- ↑ Strode 1964, p. 505–507.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, pp. 652–654.

- ↑ Fenner, Charles E. "Eulogy of Robert E. Lee". Stratford Hall.

- ↑ "History Slideshow, slide 22". Hollywood Cemetery. 2013. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved 2013-06-12.

- ↑ Urquhart, Kenneth Trist (March 21, 1959). "Seventy Years of the Louisiana Historical Association" (PDF). Alexandria, Louisiana: Louisiana Historical Association. Retrieved 2010-07-21.

- ↑ Collins 2005.

- ↑ "Hollywood Cemetery and James Monroe Tomb". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2013-10-19.

- ↑ Freemantle, Jeff. "Old Jeff Davis Hospital gets Long-term Protection". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Jeff Davis Hospital, several Houston houses receive landmark designation". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Jefferson Davis Hospital (Elder Street Lofts)". Houston Archaeological and Historical Commission. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- 1 2 Weingroff, Richard F. (April 7, 2011). "Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway". Highway History. Federal Highway Administration, United States Department of Transportation. Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ↑ "Map of the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway". World Digital Library. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ "130th Anniversary of End of American Civil War 1995". USA Stamps. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- ↑ "32c Jefferson Davis single". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved 2014-04-28.

- ↑ "Stone Mountain Memorial Issue". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved 2014-04-28.

- ↑ "Beauvoir – The Jefferson Davis Home and Presidential Library". Mississippi Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans. Retrieved 2011-07-17.

- ↑ "An Interview with Bertram Hayes-Davis". Civil War Trust. October 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ↑ "The Papers of Jefferson Davis". Rice University. Retrieved 2011-07-17.

- ↑ "The 2010 Florida Statutes (including Special Session A)". The Florida Legislature. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ↑ "2.110 Public holidays". Kentucky Legislative Research Commission. Retrieved 2013-10-16.

- ↑ "Days of public rest, legal holidays, and half-holidays". The Louisiana State Legislature. Archived from the original on April 8, 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- 1 2 "Memorial Day History". United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ↑ "Official State of Alabama Calendar". Alabama State Government. Archived from the original on December 14, 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ↑ "Mississippi Code of 1972 – SEC. 3-3-7. Legal holiday". LawNetCom, Inc. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ↑ "State holidays". Texas State Library. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ↑ "Jimmy Carter: Restoration of Citizenship Rights to Jefferson F. Davis Statement on Signing S. J. Res. 16 into Law". American Presidency Project. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "UT student government votes to remove Jefferson Davis statue". KXAN.com.

- ↑ Tom McCarthy, "Drive to call time on Confederate flag sweeps south – 150 years after civil war", The Guardian, 23 June 2015.