Jean Giraud

| Jean Giraud | |

|---|---|

Giraud at the International Festival of Comics in Łódź, October 2008 | |

| Born |

Jean Henri Gaston Giraud 8 May 1938 Nogent-sur-Marne, France |

| Died |

10 March 2012 (aged 73) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Area(s) | Writer, Artist |

| Pseudonym(s) | Gir, Mœbius, Jean Gir |

Notable works | |

| Collaborators | Alejandro Jodorowsky, Jean-Michel Charlier |

| Awards | full list |

| Spouse(s) |

Claudine Conin (m. 1967–94) Isabelle Champeval (m. 1995–2012) |

| Children | Hélène Giraud (1970), Julien Giraud (1972), Raphaël Giraud (1989), Nausicaa Giraud (1995) |

| Signature | |

|

| |

|

moebius | |

Jean Henri Gaston Giraud (French: [ʒiʁo]; 8 May 1938 – 10 March 2012) was a French artist, cartoonist and writer who worked in the Franco-Belgian bandes dessinées (BD) tradition. Giraud garnered worldwide acclaim predominantly under the pseudonym Mœbius (/ˈmoʊbiəs/;[1] French: [məbjys]) and to a lesser extent Gir (French: [ʒiʁ]), which he used for the Blueberry series and his Western themed paintings. Esteemed by Federico Fellini, Stan Lee and Hayao Miyazaki among others,[2] he has been described as the most influential bandes dessinées artist after Hergé.[3]

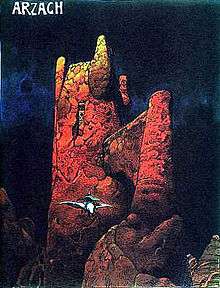

His most famous works include the series Blueberry, created with writer Jean-Michel Charlier, featuring one of the first anti-heroes in Western comics. As Mœbius he created a wide range of science fiction and fantasy comics in a highly imaginative, surreal, almost abstract style. These works include Arzach and the Airtight Garage of Jerry Cornelius. He also collaborated with avant-garde filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky for an unproduced adaptation of Dune and the comic book series The Incal.

Mœbius also contributed storyboards and concept designs to numerous science fiction and fantasy films, such as Alien, Tron, The Fifth Element and The Abyss. Blueberry was adapted for the screen in 2004 by French director Jan Kounen.

Early life

Jean Giraud was born in Nogent-sur-Marne, Val-de-Marne, in the suburbs of Paris, on 8 May 1938,[4][5] as the only child to Raymond Giraud, an insurance agent, and Pauline Vinchon who had worked at the agency.[6] When he was three years old, his parents divorced and he was raised mainly by his grandparents, who were living in the neighboring municipality of Fontenay-sous-Bois (much later, when he was the acclaimed artist, Giraud returned to live in the municipality in the mid-1970s, but was regrettably unable to buy his grandparents' house[7]). The rupture between mother and father created a lasting trauma that he explained lay at the heart of his choice of separate pen names.[8] An introverted child at first, young Giraud found solace after World War II in a small theater, located on a corner in the street where his mother lived, which concurrently provided an escape from the dreary atmosphere in post-war reconstruction era France.[9] Playing an abundance of American B-Westerns, it was there that Giraud, frequenting the theater as often as he was able to, developed a passion for the genre, as had so many other European boys his age in those times.[7]

At age 9-10 Giraud started to draw Western comics while enrolled by his single mother as a stop-gap measure in the Saint-Nicolas boarding school in Issy-les-Moulineaux for two years (and where he became acquainted with Belgian comic magazines like Spirou and Tintin), much to the amusement of his school mates.[10] In 1954, at age 16,[11] he began his only technical training at the École Supérieure des Arts Appliqués Duperré, where he, unsurprisingly, started producing Western comics, which however did not sit well with his teachers.[12] At the college, he befriended other future comic artists, Jean-Claude Mézières and fr:Pat Mallet. With Mézières in particular, in no small part due to their shared passion for science fiction, Westerns and the Far West, Giraud developed a close lifelong friendship,[13] calling him a "continuing life's adventure" in later life.[14] In 1956 he left art school without graduating to visit his mother, who had married a Mexican in Mexico, and stayed there for nine months.

It was the experience of the Mexican desert, in particular its endless blue skies and unending flat plains, now seeing and experiencing for himself the vistas that had enthralled him so much when watching westerns on the silver screen only a few years earlier, which left an everlasting, "quelque chose qui m'a littéralement craqué l'âme",[15] enduring impression on him, easily recognizable in almost all of his later seminal works.[15] After his return to France, he started to work as a full-time tenured artist for Catholic publisher Fleurus, to whom he was introduced by Mézières, who had shortly before found employment at the publisher.[16][10] In 1959–1960 he was slated for military service in, firstly the French occupation zone of Germany, and subsequently Algeria,[17] in the throes of the vicious Algerian War at the time. Fortunately for him however, he somehow managed to escape frontline duty as he – being the only service man available at the time with a graphics background – served out his military obligations as illustrator on the army magazine 5/5 Forces Françaises, besides being assigned to logistic duties.[7]

Career

Western comics

At 18, Giraud was drawing his own humorous, Morris inspired, Western comic two-page shorts, Frank et Jeremie, for the magazine Far West, his very first free-lance commercial sales.[18] Magazine editor Marijac thought young Giraud gifted with a knack for humorous comics, but none whatsoever for realistically drawn comics, and advised him to continue in the vein of Frank et Jeremie.[10]

Fleurus (1956-1958)

Tenured at publisher Fleurus from 1956 to 1958 after his first sales, Giraud did so, but concurrently continued to steadfastly create realistically drawn Western comics (alongside several others of a French historical nature) and illustrations for magazine editorials in their magazines Fripounet et Marisette, fr:Cœurs Valiants and Ames Valliantes – all of them of a strong edifying nature aimed at France's adolescent youth – , up to a point that his realistically drawn comics had become his mainstay. Among his realistic Westerns was a comic called "Le roi des bisons" ("King of the Buffalo" – has seen an English publication[16]), and another called "Un géant chez lez Hurons" ("A Giant with the Hurons").[19] Actually, several of his Western comics, including "King of the Buffalo", featured the same protagonist Art Howell, and these can be considered as Giraud's de facto first realistic Western series, as he himself did in effect, since he, save the first one, endowed these stories with the subtitle "Un aventure d'Art Howell".[20] It was for Fleurus that Giraud also illustrated his first three books.[21] Already in this period his style was heavily influenced by his later mentor, Belgian comic artist Joseph "Jijé" Gillain, who at that time was the major source of inspiration for an entire generation of young aspiring French comic artists, including Giraud's friend Mézières, interested in doing realistically drawn comics.[16] How major Jijé's influence was on these young artists, was amply demonstrated by the Fleurus publications these youngsters submitted their work to, as their work strongly resembled each other. For example, two of the books Giraud illustrated for Fleurus, were co-illustrated with Guy Mouminoux, another name of some future renown in the Franco-Belgian comic world, and Giraud's work can only be identified, because he signed his work, whereas Mouminoux did not sign his. While not ample, Giraud's earning at Fleurus were just enough to allow him – disenchanted as he was with the courses, prevalent atmosphere and academic discipline – to quit his art academy education after only two years, though he came to somewhat regret the decision in later life.[22]

Jijé apprenticeship (1961-1962)

Shortly before he entered military service, Giraud visited his idol at his home for the first time with Mézières and Mallet, followed by a few visits on his own to see the master at work for himself. In 1961, returning from military service and his stint on 5/5 Forces Françaises, Giraud, not wanting to return to Fleurus as he felt that he "had to do something else, if he ever wanted to evolve", became an apprentice of Jijé on his invitation, after he saw that Giraud had made artistic progress during his stay at 5/5 Forces Françaises.[23] Jijé was then one of the leading comic artists in Europe and known for his gracious tendency to voluntarily act as a mentor for young, aspiring comic artists, of which Giraud was only one, going even as far as opening up his family home in Champrosay for days on end for these youngsters, which, again, included Giraud.[24] In this Jijé resembled Belgian comic grand-master Hergé, but unlike Jijé, Hergé only did so on a purely commercial basis, never on a voluntarily one. For Jijé, Giraud created several other shorts and illustrations for the short-lived magazine Bonux-Boy (1960/61), his first comic work after military service, and his penultimate one before embarking on Blueberry.[25] In this period, Jijé used his apprentice for the inks on an outing of his Western series Jerry Spring – after whom Giraud had, unsurprisingly, modeled his Art Howell character previously – , "The Road to Coronado", which Giraud inked.[17] Actually, Jijé had intended his promising pupil for the entirety of the story art, but the still unexperienced Giraud, used as he was to work under the relaxed conditions at Fleurus, found himself overwhelmed by the strict time schedules a production for a periodical (Spirou in this case) demanded. Conceding that he had been a bit too cocky and ambitious, Giraud stated, "I started the story all by myself. But after a week I had only finished half a plate, and, aside from being soaked with my sweat, it was a complete disaster. So Joseph went on to do the penciling, whereas I did the inks."[10] Even though Giraud did loose touch with his mentor eventually, he has never forgotten what "his master" had provided him with, both "aesthetically and professionally",[26] the fatherless Giraud gratefully stating in later life, "It was as if he had asked me «Do you want me to be your father?», and if by a miracle, I was provided with one, a[n] [comic] artist no less!".[24]

Hachette (1962-1963)

Pursuant his stint at Jijé's, Giraud was again approached by friend Mézières if he was interested to work alongside him as an illustrator on Hachette's ambitious multi-volume L'histoire des civilisations history reference work.[27] Spurred on by Jijé, who considered the opportunity a wonderful one for his pupil, Giraud accepted. Though he considered the assignment a daunting one, having to recreate imaginary in oil paints from historical objects and imagery, it, besides being the best paying job he had until then held, was nonetheless a seminal appointment.[24] At Hachette Giraud discovered that he had a knack for creating art in gouaches, something that served him well not that much later when creating Blueberry magazine/album cover art,[28] as well as for his 1968 side-project Buffalo Bill: le roi des éclaireurs history book written by fr:George Fronval, for whom Giraud provided two-thirds of the illustrations in gouache, including the cover.[29] The assignment at Hachette being cut short because of his invitation to embark on Fort Navajo, meant he only participated on the first three to four volumes of the book series, leaving the completion to Mézières. In the Pilote era, Giraud additionally provided art in gouache for two Western themed vinyl record music productions as sleeve art,[30] as well as the covers for the first seven outings in the French language edition of the Morgan Kane Western novel series written by Louis Masterson.[31] Much of his Western-themed gouache artwork of this era, including that of Blueberry, has been collected in the 1983 artbook "Le tireur solitaire".[32]

Aside for its professional importance, Giraud's stint at Hachette also turned out to be of personal importance as well, as he met Claudine Conin, an editorial researcher at Hachette, and who described her future husband as being at the time "funny, uncomplicated, friendly, a nice boy next-door", but on the other hand "mysterious, dark, intellectual", already recognizing that he had all the makings of a "visionary", long before others did.[33] Married in 1967, after Giraud had become the recognized Blueberry artist, the couple had two children, Hélène (b:1970) and Julien (b:1972). Daughter Hélène in particular seemed to have inherited her father's graphics talents as she too has carved out a career as a graphics artist in the animation industry,[34] earning her a 2014 French civilian knighthood, the same her father had already received in 1985. Besides raising their children, wife Claudine not only took care of the business aspects of her husband's art work, but has on occasion also contributed to it as well as colorist.[35] The 1976 feminist fantasy short story, "La tarte aux pommes",[36] was written by her under her maiden name. Additionally, the appearance of a later, major character in Giraud's Blueberry series, Chihuahua Pearl, was in part based on Claudine's looks.[37] The Mœbiusienne 1973 fantasy road trip short story "La déviation",[38] created as "Gir"[39] before the artist fully embarked on his Mœbius career, featured the Giraud family as the protagonists, save Julien.

Pilote (1963-1979)

In October 1963, Giraud and writer Jean-Michel Charlier started the comic strip Fort Navajo for the by Charlier co-founded Pilote magazine, issue 210.[40] At this time the affinity between the styles of Giraud and Jijé (who in effect had been Charlier's first choice for the series, but who was reverted to Giraud by Jijé) was so close that Jijé penciled several pages for the series when Giraud went AWOL. In effect, when "Fort Navajo" started its run, Pilote received angry letters, accusing Giraud of plagiarism, which was however foreseen by Jijé and Giraud. Shirking off the accusations, Jijé encouraged his former pupil to stay the course instead, thereby propping up his self-confidence.[24] The first time Jijé had to fill in for Giraud, was during the production of the second story, "Thunder in the West" (1964), when the still inexperienced Giraud, buckling under the stress of having to produce a strictly scheduled magazine serial, suffered from a nervous breakdown, with Jijé taking on plates 28–36.[41] The second time occurred one year later, during the production of "Mission to Mexico (The Lost Rider)", when Giraud unexpectedly packed up and left to travel the United States,[42] and, again, Mexico; yet again former mentor Jijé came to the rescue by penciling plates 17–38.[43][44] While the art style of both artists had been nearly indistinguishable from each other in "Thunder in the West", after Giraud resumed work on plate 39 of "Mission to Mexico", a clearly noticeable style breach was now observable, indicating that Giraud was now well on his way to develop his own signature style, eventually surpassing that of his former teacher Jijé, who, impressed by his former pupil's achievements, has later coined him the "Rimbaud de la BD".[24]

The Lieutenant Blueberry character, whose facial features were based on those of the actor Jean-Paul Belmondo, was created in 1963 by Charlier (scenario) and Giraud (drawings) for Pilote.[45][46] While the Fort Navajo series had originally been intended as an ensemble narrative, it quickly gravitated towards having Blueberry as its central figure. His featured adventures, in what was later called the Blueberry series, may be Giraud's best known work in native France and the rest of Europe, before later collaborations with Alejandro Jodorowsky. The early Blueberry comics used a simple line drawing style similar to that of Jijé, and standard Western themes and imagery (specifically, those of John Ford's US Cavalry Western trilogy, with Howard Hawk's 1959 Rio Bravo thrown in for good measure for the sixth, one-shot title "The Man with the Silver Star"), but gradually Giraud developed a darker and grittier style inspired by, firstly the 1970 Westerns Soldier Blue and Little Big Man (for the "Iron Horse" story-arc), and subsequently by the Spaghetti Westerns of Sergio Leone and the dark realism of Sam Peckinpah in particular (for the "Lost Goldmine" story-arc and beyond).[47] With the fifth album, "The Trail of the Navajos", Giraud established his own style, and after both editorial control and censorship laws were loosened in the wake of the May 1968 social upheaval in France – the former in no small part due to the revolt key comic artists, Giraud chief among them, staged a short time thereafter in the editorial offices of Dargaud, the publisher of Pilote, demanding and ultimately receiving more creative freedom from editor-in-chief René Goscinny[lower-alpha 1] – , the strip became more explicitly adult, and also adopted a wider range of thematics.[3][44] The first Blueberry album penciled by Giraud after he had begun publishing science fiction as Mœbius, "Nez Cassé" ("Broken Nose"), was much more experimental than his previous Western work.[44] While the editorial revolt at Dargaud has effectively become the starting point of the emancipation of the French comic world,[49] Giraud has admitted that it had also caused a severe breach in his hitherto warm relationship with the conservative Goscinny, and which was has never been fully mended.[50]

Giraud left the series and publisher in 1974, partly because he was tired of the publication pressure he was under in order to produce the series, partly because of an emerging royalties conflict, but mostly because he wanted further explore and develop his "Mœbius" alter ego, in particular because Jodorowsky, who was impressed by the graphic qualities of Blueberry, had already invited him to come over to Los Angeles previously, to start production design on his Dune movie project, and which constituted the first Jodorowsky/Mœbius collaboration. Giraud was so eager to return on the project during a stopover from the United States while the project was in hiatus, that he greatly accelerated the work on the "Angel Face" outing of Blueberry he was working on at the time, shearing off weeks from its originally intended completion.[51] The project fell through though, and after he had returned definitely to France later that year, he started to produce comic work under this pseudonym that was published in the magazine he co-founded, Métal Hurlant, which started its run in December 1974 and revolutionized the Franco-Belgian comic world in the process. He returned to the series in 1979 with "Nez Cassé" as a free-lancer.

It was Jodorowsky who introduced Giraud to the writings of Carlos Castaneda, who had written a series of books that describe his training in shamanism, particularly with a group whose lineage descended from the Toltecs. The books, narrated in the first person, related his experiences under the tutelage of a Yaqui "Man of Knowledge" named Don Juan Matus. Castaneda's writings made a deep and everlasting impression on Giraud, already open to Native-Mexican folk culture due to his three previous extended trips to the country (he had visited the country a third time in 1972[52]), and it did influence his art as "Mœbius", particularly in regard to dream sequences, though he was not quite able to work in such influences in his mainstream Blueberry comic.[lower-alpha 2][54] Yet, unbeknownst to writer Charlier, he did already sneak in some Castaneda elements in "Nez Cassé".[55] Castaneda's influence reasserted itself in full in Giraud's later life, having worked in elements more openly after Charlier's death in his 1999 Blueberry outing "Geronimo l'Apache", and was to become a major element for his Blueberry 1900-project, which however, had refused to come to fruition for extraneous reasons.[56][57]

Even though Giraud had vainly tried to introduce his Blueberry co-worker to the writings of Castaneda, Charlier, being of a previous generation, conservative in nature and wary of science fiction in general, has never understood what his younger colleague tried to achieve as "Mœbius". Nonetheless, he never tried to hinder Giraud in the least, as he understood that an artist of Giraud's caliber needed a "mental shower" from time to time. Furthermore, Charlier was very appreciative of the graphic innovations Giraud ported over from his work as "Mœbius" into the mainstream Blueberry series, most specifically "Nez Cassé", making him "one of the all-time greatest artists in the comic medium", as Charlier himself worded it in 1982.[58] Artist fr:Michel Rouge, who was taken on by Giraud in 1980 for the inks of "La longue marche" ("The Long March") painted a slightly different picture though. Already recognizing that the two men were living in different worlds, he noted that Charlier was not pleased with Giraud taking on an assistant, afraid that it might have been a prelude to him leaving the series in order to pursue his "experimentations" as Mœbius further. While Charlier was willing to overlook Giraud's "philandering" in his case only, he was otherwise of the firm conviction that artists, especially his own, should totally and wholeheartedly devote themselves to their craft, as Charlier had always considered the medium.[59] Even Giraud was in later life led to believe that Charlier apparently "detested" his other work, looking upon it as something akin to "treason", though his personal experiences with the author was that he had kept an "open mind" in this regard, at least in his case. According to Giraud, Charlier's purported stance negatively influenced his son Philippe, causing their relationship to rapidly deteriorate into open animosity, after the death of his father.[56][60]

Post-Pilote (1979-2007)

In late 1979, the long-running disagreement Charlier and Giraud had with their publishing house Dargaud over the residuals from Blueberry came to a head. They began the Western comic Jim Cutlass as a means to put the pressure on Dargaud.[56] It did not work, and Charlier and Giraud turned their back on the parent publisher definitively,[48] leaving for greener pastures elsewhere, and in the process taking all of Charlier's co-creations with them. It would be nearly fifteen years before the Blueberry series returned to Dargaud after Charlier died. After the first album, "Mississippi River", first serialized in Métal hurlant and for two decades remaining an one-shot, Giraud took on scripting the revitalized series after Charlier had died, while leaving the artwork to fr:Christian Rossi.[61]

When Charlier, Giraud's collaborator on Blueberry, died in 1989, Giraud assumed responsibility for the scripting of the main series, the last outing of which, "Apaches", released in 2007. Blueberry has been translated into 19 languages, the first English book translations being published in 1977/78 by UK publisher Egmont/Methuen, though its publication was cut short after only four volumes. The original Blueberry series has spun off a prequel series called Young Blueberry, but the artwork was after 1984 left to Colin Wilson and later fr:Michel Blanc-Dumont after the first three original volumes in that series, as well as the by Giraud written, but by William Vance penciled 1991-2000 intermezzo series called Marshal Blueberry.[45]

While Giraud has garnered universal praise and acclaim for his work as "Mœbius" (especially in the US, the UK and Japan), it should be noted that as "Gir", Blueberry has always remained his most successful and most recognized work in native France itself and in mainland Europe, despite its artist developing somewhat of a love/hate relationship with his co-creation in later life, which was exemplified by him regularly taking an extended leave of absence from his co-creation. That Blueberry has always remained his primary source of income, allowing him to fully indulge in his artistic endeavors as Mœbius, was admitted as such by Giraud as early as 1979, "If a album of Moebius is released, about 10.000 people are interested. A Blueberry album sells at least 100.000 copies [in France],"[62][55] and as late as 2005, "Blueberry is in some ways the "sponsor" of Moebius, for years now."[63]

Science fiction and fantasy comics

The "Mœbius" pseudonym, which Giraud came to use for his science fiction and fantasy work, was born in 1963,[17] while he was working on the Hachette project, as he did not like "to work on paintings alone all day", and "like an alcoholic needing his alcohol" had to create comics.[64] In a satire magazine called Hara-Kiri, Giraud used the name for 21 strips in 1963–64. Though Giraud enjoyed the artistic freedom and atmosphere at the magazine greatly, he eventually gave up his work there as Blueberry, on which he had embarked in the mean time, demanded too much of his energy, aside from being a better paid job. Magazine editor-in-chief Cavanna was loath to let Giraud go, not understanding why Giraud would want to waste his talents on a "kiddy comic".[64] Subsequently, the pseudonym went unused for a decade, that is for comics at least, as Giraud continued its use for side-projects as illustrator. In the late 1960s-early 1970s, Giraud provided interior front, and back flyleaf illustrations as Mœbius for several outings in the science fiction book club series fr:Club du livre d'anticipation, a limited edition hardcover series, collecting work from seminal science fiction writers, from French publisher fr:Éditions OPTA, continuing to do so throughout the 1970s with several additional covers for the publisher's Fiction (the magazine that introduced Giraud to science fiction at age 16[65]) and fr:Galaxie-bis science fiction magazine and pocket book series. Additionally, this period in time also saw four vinyl record music productions endowed with Mœbius sleeve art.[30] Much of this illustration art has been reproduced in Giraud's first art book as Mœbius, aptly entitled "Mœbius", released in 1980.[39][66] There actually had also been a personal reason as well for Giraud to suspend his career as Mœbius comic artist; after he had returned from his second trip from Mexico, he found himself confronted with the artist's version of a writer's block as far as Mœbius comics were concerned, partly because Blueberry consumed all his energy. "For eight months I tried, but I could not do it, so I quit", stated Giraud additionally.[64] Giraud's statement notwithstanding though, he did a couple of Hara-Kiriesque satirical comic shorts for Pilote in the early 1970s, but under the pseudonym "Gir", most of which reprinted in the comic book Gir œuvres: "Tome 1, Le lac des émeraudes",[67] also collecting shorts he had created for the Fleurus magazines, Bonux-Boy, and the late-1960s TOTAL Journal magazine.[25]

L'Écho des savanes (1974)

In 1974 he truly revived the Mœbius pseudonym for comics, and the very first, 12-page, story he created as such – while on one of his stopovers from America when the Dune production was in a lull – was "Cauchemar Blanc" ("White Nightmare"), published in the magazine L'Écho des savanes, issue 8, 1974. The black & white story dealt with the racist murder of an immigrant of North-African descent, and stands out as one of the very few emphatic socially engaged works of Giraud.[68] Bearing in mind Giraud's fascination with the Western genre in general and the cultural aspects in particular of Native-Americans – and whose plight Giraud had always been sympathetic to[lower-alpha 3] – , it is hardly a surprise that two later examples of such rare works were Native-American themed.[lower-alpha 4] These concerned the 2-page short story "Wounded Knee",[70] inspired by the eponymous 1973 incident staged by Oglala Lakota, and the 3-page short story "Discours du Chef Seattle", first published in the artbook "Made in L.A."[71] ("The Words of Chief Seattle", in Epic's "Ballad for a Coffin"). Giraud suddenly bursting out onto the comic scene as "Mœbius", caught European readership by surprise, and it took many of them a couple of years before the realization had sunk in that "Jean [Gir]raud" and "Mœbius" were, physically at least, one and the same artist.[68]

It was when he was brainstorming with the founding editors of the magazine (founded by former Pilote friends and co-artists in the wake of the revolt at the publisher, when they decided to strike out on their own), that Giraud came up with his first major Mœbius work, "Le bandard fou" ("The Horny Goof"). Released directly as album (a first for Mœbius comics) in black & white by the magazine's publisher,[72] the humorous and satirical story dealt with a law-abiding citizen of the planet Souldaï, who awakens one day, only to find himself with a permanent erection. Pursued through space and time by his own puritanical authorities, who frown upon the condition, and other parties, who have their own intentions with the hapless bandard, he eventually finds a safe haven on the asteroid Fleur of Madame Kowalsky, after several hilarious adventures. When discounting the as "Gir" signed "La déviation", it is in this story that Giraud's signature, minute "Mœbius" art style, for which he became famed not that much later, truly comes into its own. Another novelty introduced in the book, is that the narrative is only related on the right-hand pages; the left-hand pages are taken up by one-page panels depicting an entirely unrelated cinematographic sequence of a man transforming after he has snapped his fingers. The story did raise some eyebrows with critics accusing Giraud of pornography at the time, but one reviewer put it in perspective when stating, "Peut-être Porno, mais Graphique!", which loosely translates as "Porn maybe, but Graphic Art for sure!".[73] In the editorial of the 1990 American edition, Giraud has conceded that he was envious of what his former Pilote colleagues had achieved with L'Écho des savanes in regard to creating a free, creative environment for their artists, he had already enjoyed so much back at Hara-Kiri, and that it was an inspiration for the endeavor, Giraud embarked upon next.

Métal hurlant (1974-1982)

Later that year, after Dune was permanently canceled with him definitively returning to France, Giraud became one of the founding members of the comics art group and publishing house "Les Humanoïdes Associés", together with fellow comic artists Jean-Pierre Dionnet, Philippe Druillet (likewise Pilote colleagues) and (outsider) financial director Bernard Farkas. In imitation of the example set by the L'Écho des savanes founding editors, it was therefore as such also an indirect result of the revolt these artists had previously staged at Pilote, and whose employ they had left for the undertaking.[74] Together they started the monthly magazine Métal hurlant ("Screaming metal") in December 1974,[75] and for which he had temporarily abandoned his Blueberry series. The translated version was known in the English-speaking world as Heavy Metal, and started its release in April 1977, actually introducing Giraud's work to North-American readership.[76] Mœbius' famous serial "The Airtight Garage" and his groundbreaking "Arzach" both began in Métal hurlant.[77] Unlike Hara-Kiri and L'Écho des savanes though, whose appeal has always remained somewhat limited to the socially engaged satire and underground comic scenes, it was Métal hurlant in particular that revolutionized the world of Franco-Belgian bandes dessinées,[49] whereas its American cousin left an indelible impression on a generation of not only American comic artists, but on film makers as well as evidenced below.

Starting its publication in the first issue of Métal hurlant, "Arzach" is a wordless 1974-1975 comic, executed directly in color and created as a conscious attempt to breathe new life into the comic genre which at the time was dominated by American superhero comics in the United States, and by the traditional, adolescent oriented bandes dessinée in Europe.[78] It tracks the journey of the title character flying on the back of his pterodactyl through a fantastic world mixing medieval fantasy with futurism. Unlike most science fiction comics, it is, save for the artful executed story titles, entirely devoid of captions, speech balloons and written sound effects. It has been argued that the wordlessness provides the strip with a sense of timelessness, setting up Arzach's journey as a quest for eternal, universal truths.[2] The short stories "L'Homme est-il bon?" ("Is Man Good?", in issue 10, 1976, after the first publication in Pilote, issue 744, 1974, which however woke Giraud up to the "unbearable realization" that he was "enriching" the publisher with his Mœbius work, thereby expediting his departure.[79]), "Ballade" ("The Ballade", 1977 and inspired by the poem "Fleur" by French poet Arthur Rimbaud[80]), "Ktulu" (issue 33bis, 1978) and "Citadelle aveugle" ("The White Castle", in issue 51, 1980 and oddly enough signed as "Gir") were examples of additional stories Giraud created directly in color, shortly after "Arzach". 1976 saw the Métal hurlant, issues 7-8, publication of "The Long Tomorrow", written by Dan O'Bannon in 1974 during lulls in the pre-production of Jodorowsky's Dune.[81]

His series The Airtight Garage, starting its magazine run in issue 6, 1976, is particularly notable for its non-linear plot, where movement and temporality can be traced in multiple directions depending on the readers' own interpretation even within a single planche (page or picture). The series tells of Major Grubert, who is constructing his own multi-level universe on an asteroid named Fleur (from the "Bandard fou" universe incidentally, and the first known instance of the artist's attempts of tying all his "Mœbius" creations into one coherent Airtight Garage universe), where he encounters a wealth of fantastic characters including Michael Moorcock's creation Jerry Cornelius.[82]

1978 marked the publication of the 54-page "Les yeux du chat" ("Eyes of the Cat"). The dark, disturbing and surreal tale dealt with a blind boy in a non-descript empty cityscape, who has his pet eagle scout for eyes, which it finds by taking these from a street cat and offering them to his awaiting companion who, while grateful, expresses his preference for the eyes of a child. The story premise originated from a brainstorming session Alejandro Jodorowsky had with his fellows of the Académie Panique, a group concentrated on chaotic and surreal performance art, as a response to surrealism becoming mainstream.[83] Jodorowksy worked out the story premise as a therapy to alleviate the depression he was in after the failure of his Dune project and presented the script to Giraud in 1977 during a visit to Paris. Deeming the story too short for a regular, traditional comic, it was Giraud who suggested the story to be told on the format he had already introduced in "Le bandard fou", to wit, as single panel pages. On recommendation of Jodorowsky, he refined the format by relating the eagle's quest on the right-hand pages, while depicting the awaiting boy in smaller single panel left-hand pages from a contra point-of-view. Giraud furthermore greatly increased his already high level of detail by making extensive use of zipatone for the first time.[84] Considered a key and seminal work, both for its art and storytelling, setting Jodorowsky off on his career as comic writer,[85] the art evoked memories of the wood engravings from the 19th century, including those of Gustave Doré, Giraud discovered and admired in the books of his grandparents, when he was living there in his childhood, though it – like "La déviation" – has remained somewhat of an one-shot in Giraud's body of work in its utilization of such a high detail level.[86] The story, printed on yellow paper to accentuate the black & white art, was originally published directly as a to 5000 copies limited book, as a gift item for relations of the publisher.[87] It was only after expensive pirate editions started to appear that the publisher decided to make the work available commercially on a wider scale, starting in 1981.[88][89] Jodorowsky had intended the work to be the first of a trilogy, but that never came to fruition.[90]

In a certain way "Les yeux du chat" concluded a phase that had started with "La Déviation",[85] and this viewpoint was adhered to by the publisher who had coined the era "Les années Métal Hurlant" on one of its latter-day anthologies.[91] The very first "Mœbius" anthology collection the publisher released as such, was the 1980-1985 Moebius œuvres complètes six-volume collection of which two, volumes 4, "La Complainte de l'Homme Programme"[92] and 5, "Le Désintégré Réintégré"[93] ( (the two of them in essence comprising an expanded version of the 1980 original[66]), were Mœbius art books.[94] It also concluded a phase in which Giraud was preoccupied in a "characteristic period in his life" in which he was "very somber and pessimistic about my life", resulting in several of his "Mœbius" stories of that period ending in death and destruction.[95] These included the poetic "Ballade", in which Giraud killed off the two protagonists, something he came to regret a decade later in this particular case.[80]

In the magazine's issue 58 of 1980 Giraud started his famous L'Incal series in his third collaboration with Jodorowsky.[96] However, by this time Giraud felt that his break-out success as "Mœbius" had come at a cost. He had left Pilote to escape the pressure and stifling conditions he was forced to work under, seeking complete creative freedom, but now it was increasingly becoming "as stifling as it had been before with Blueberry", as he conceded in 1982, adding philosophically, "The more you free yourself, the more powerless you become!".[97] How deeply ingrained this sentiment was, was evidenced in a short interview in Métal Hurlant, issue 82, later that year, where an overworked Giraud stated, "I will finish the Blueberry series, I will finish the John Difool [Incal] series and then I'm done. Then I will quit comics!" At the time he had just finished working as storyboard, and production design artist on the Movie Tron, something he had enjoyed immensely. Fortunately for his fans, Giraud did not act upon his impulse as history has shown, though he did take action to escape the hectic Parisian comic scene in 1980 by moving himself and his family as far away from Paris as possible in France, by relocating to the small city of Pau at the foothills of the Pyrenees.[55] It was while he was residing in Pau that Giraud started to take an interest in the teachings of Jean-Paul Appel-Guéry, becoming an active member of his group and partaking in their gatherings.[98]

Tahiti (1983-1984)

From 1985 to 2001 he also created his six-volume fantasy series Le Monde d'Edena, which has appeared in English as The Aedena Cycle.[99] The stories were strongly influenced by the teachings of Jean-Paul Appel-Guéry,[lower-alpha 5] and Guy-Claude Burger's instinctotherapy. In effect, Giraud and his family did join Appel-Guéry's commune on Tahiti in 1983, until late 1984, when the family moved to the United States, where Giraud set up shop firstly in Santa Monica, and subsequently in Venice and Woodland Hills, California.[101] Giraud's one-shot comic book "La nuit de l'étoile"[102] was co-written by Appel-Guéry, and has been the most visible manifestation of Giraud's stay on Tahiti, aside from the artbooks "La memoire du futur"[103] and "Venise celeste".[104] Concurrently collaborating on "La nuit de l'étoile" was young artist Marc Bati, also residing at the commune at the time, and for whom Giraud afterwards wrote the comic series Altor (The Magic Crystal), while in the US.[105] It was under the influence of Appel-Guéry's teachings that Giraud conceived a third pseudonym, Jean Gir – formally introduced to the public as "Jean Gir, Le Nouveau Mœbius" in "Venise celeste" (p. 33), though Giraud had by the time of publication already dispensed with the pseudonym himself – , which appeared on the art he created while on Tahiti, though not using it for his Aedena Cycle. Another member of the commune was Paula Salomon, for whom Giraud had already illustrated her 1980 book "La parapsychologie et vous".[106] Having to move statesite for work, served Giraud well, as he became increasingly disenchanted at a later stage with the way Appel-Guéry ran his commune on Tahiti, in the process dispensing with his short-lived third pseudonym.[15] His stay at the commune though, had practical implications on his personal life; Giraud gave up eating meat, smoking, coffee, alcohol and the use of mind-expanding substances, adhering to his newfound abstinence for the most part for the remainder of his life.[107]

During his stay on Tahiti, Giraud had co-founded his second publishing house under two concurrent imprints, Éditions Gentiane[108] (predominantly for his work as Gir, most notably Blueberry) and Éditions Aedena[109] (predominantly for his work as Mœbius, and not entirely by coincidence named after the series he was working on at the time), together with friend and former editor at Les Humanoïdes Associés, fr:Jean Annestay, for the express purpose to release his work in a more artful manner, such as limited edition art prints, art books ("La memoire du futur" was first released under the Gentiane imprint, and reprinted under that of Aedena) and art portfolios. Both men had already released the very first such art book in the Humanoïdes days,[66] and the format then conceived – to wit, a large 30x30cm book format at first, with art organized around themes, introduced by philosophical poetry by Mœbius – was adhered to for later such releases, including "La memoire du futur".

Marvel Comics (1984-1989)

"There were thousands of professionals who knew my work. That has always amazed me every time I entered some graphics, or animation studio, at Marvel or even at George Lucas'. Mentioning the name Jean Giraud did not cause any of the present pencillers, colorists or storyboard artists to even bat an eye. Yet, whenever I introduced myself as "Mœbius", all of them jumped up to shake my hand. It was incredible!"— Giraud, Cagnes-sur-Mer 1988, on his notoriety as "Mœbius" in the United States.[110]

After having arrived in California, Giraud's wife Claudine set up Giraud's third publishing house Starwatcher Graphics in 1985,[111] essentially the US branch of Gentiane/Aedena with the same goals, resulting in the release of, among others, the extremely limited art portfolio La Cité Feu, a collaborative art project of Giraud with Geoff Darrow (see below). However, due to their unfamiliarity with the American publishing world, the company did not do well, and in an effort to remedy the situation Claudine hired the French/American editor couple Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier, whom she had met at the summer 1985 San Diego ComicCon, as editors-in-chief for Starwatcher, also becoming shareholders in the company.[110] Already veterans of the US publishing world (and Mœbius fans), it was the Lofficier couple that managed to convince editor-in-chief Archie Goodwin of Marvel Comics to publish most of Moebius' hitherto produced work on a wider scale in the US – contrary to the Heavy Metal niche market releases by HM Communications in the late 1970s – in graphic novel format trade editions, under its Epic imprint from 1987-1994. These incidentally, included three of Mœbius' latter-day art books, as well as his Blueberry Western comic.[112]

It was for the Marvel/Epic publication effort that it was decided to dispense with the "Jean [Gir]aud"/"Mœbius" dichotomy – until then strictly adhered to by the artist – , as both the artist's given name and his Blueberry creation were all but unknown in the English speaking world. This was contrary to his reputation as "Mœbius", already acquired in the Heavy Metal days, and from then on used for all his work in the English speaking world (and Japan), though the dichotomy remained adhered to elsewhere, including native France.[113]

A two-issue Silver Surfer miniseries (later collected as Silver Surfer: Parable), written by Stan Lee and drawn by Giraud (as Mœbius), was published through Marvel's Epic Comics imprint in 1988 and 1989. According to Giraud, this was his first time working under the Marvel method instead of from a full script, and he has admitted to being baffled by the fact that he already had a complete story synopsis on his desk only two days after he had met Stan Lee for the first time, having discussed the – what Giraud then assumed a mere – proposition over lunch.[75] This miniseries won the Eisner Award for best finite/limited series in 1989. Mœbius' version was discussed in the 1995 submarine thriller Crimson Tide by two sailors pitting his version against those of Jack Kirby, with the main character played by Denzel Washington emphasizing the Kirby one being the better of the two. Becoming aware of the reference around 1997, Giraud was later told around 2005 by the movie's director Tony Scott, that it was he who had written in the dialog as an homage to the artist on behalf of his brother Ridley, a Mœbius admirer, and not (uncredited) script doctor Quentin Tarentino (known for infusing his works with pop culture references) as he was previously led to believe. An amused Giraud quipped, "It's better than a big stature, because in a way, I can not dream of anything better to be immortal [than] being in a movie about submarines!"[1]

As a result, from his cooperation with Marvel, Giraud delved deeper into the American super hero mythology and created super hero art stemming from both Marvel and DC Comics, which were sold as art prints, posters or included in calendars.[114] Even as late as 1997, Giraud had created cover art for two DC comic book outings, Hardware (Vol. 1, issue 49, March 1997) and Static (Vol. 1, issue 45, March 1997), after an earlier cover for Marvel Tales (Vol. 2, issue 253, September 1991). Another project Giraud embarked upon in his "American period", was for a venture into that other staple of American pop culture, trading cards. Trading card company Comic Images released a "Mœbius Collector Cards" set in 1993, featuring characters and imagery from all over his Mœbius universe, though his Western work was excluded. None of the images were lifted from already pre-existing work, but was especially created anew by Giraud the year previously.

Although Giraud had taken up residence in California for five years – holding a temporary residence (the O-1 "Extraordinary Ability" category,[115] including the "International Artist" status[116]) visa – , he maintained a transient lifestyle, as his work had him frequently travel to Belgium and native France (maintaining a home in Paris), as well as to Japan, for extended periods of time. His stay in the United States was an inspiration for his aptly called Made in L.A. art book,[71] and much of his art he had produced in this period of time, including his super hero art, was reproduced in this, and the follow-up art book Fusions,[117] the latter of which having seen a translation in English by Epic.

Giraud's extended stay in the US, garnered him an 1986 Inkpot Award, an additional 1991 Eisner Award, as well as three Harvey Awards in the period 1988–1991 for the various graphic novel releases by Marvel. It was in this period that Giraud, who had already picked up Spanish as a second language as a result from his various trips to Mexico and his dealings with Jodorowsky and his retinue, also picked up sufficient language skills to communicate in English.[118][1]

Latter-day work

In late summer 1989, Giraud returned to France, definitively as it turned out, though that was initially not his intent. His family had already returned to France earlier, as his children wanted to start their college education in their native county and wife Claudine had accompanied them to set up home in Paris. However, it also turned out that his transient lifestyle had taken its toll on the marriage, causing the couple to drift apart, and it was decided upon his return to enter into a "living apart together" relationship, which allowed for an "enormous freedom and sincerity" without "demands and frustrations" for both spouses, according to the artist.[119] Additionally, Giraud had met Isabelle Champeval during a book signing in Venice, Italy in February 1984, and entered into a relationship with her in 1987, with resulted in the birth of second son Raphaël in 1989. Giraud's marriage with Claudine was legally ended in December 1994, without much drama according to Giraud, as both spouses had realized that "each wanted something different out of life".[15] Exemplary of the marriage ending without any ill will was, that Claudine was emphatically acknowledged for her contributions in the 1997 artbook "Blueberry's",[120] and the documentary made fore the occasion of its release. Giraud and Isabelle were married on 13 May 1995, and the union resulted in their second child, daughter Nausicaa, the same year.[6] For Giraud his second marriage was of such great personal importance, that he henceforth considered his life divided in a pre-Isabelle part and a post-Isabelle part, having coined his second wife "the key to the whole grand design".[121] Isabelle's sister and Giraud's sister-in-law, Claire, became a regular contributor as colorist on Giraud's latter-day work.[122]

The changes in his personal life were also accompanied with changes in his business holdings during 1988-1990. His co-founded publishing house Gentiane/Aedena went into receivership in 1988, going bankrupt a short time thereafter. The American subsidiary Starwatcher Graphics followed in its wake,[111] partly because it was a shared marital possession of the original Giraud couple. In 1989 Giraud sold his shares in Les Humanoïdes Associés to Fabrice Giger, thereby formally severing his ownership ties with the publisher, which however remained the regular publisher of his Mœbius work from the Métal hurlant era, including L'Incal. Together with Isabelle he founded Stardom in 1990, his first true family operated business, according to Giraud,[123] with the to 1525 copies limited mini art portfolio "Mockba - carnet de bord" becoming the company's first recorded publication in September the same year.[124] Apart from being a publishing house, it was concurrently an art gallery, located on 27 Rue Falguière, 75015 Paris, organizing themed exhibitions on a regular basis. In 1997, the company was renamed Moebius Production – singular, despite the occasional and erroneous use of the plural, even by the company itself.[125] The company, in both publishing and art gallery iterations, is as of 2017 still being run by Isabelle Giraud and her sister Claire.[126]

While Giraud was in the midst of Blueberry's "OK Corral" cycle, he also embarked on a new sequel cycle of his acclaimed Incal main series, called Après l'Incal (After the Incal). Yet, after he had penciled the first outing in the series, "Le nouveau rêve",[127] he found himself confronted with "too many things that attract me, too many desires in all the senses", causing him to be no longer able to "devote myself to the bande dessinée as befitting a professional in the traditional sense". Despite repeated pleas to convince Giraud otherwise, it left writer Jodorowsky with no other recourse than to start anew with a new artist.[128] This insight had repercussions though, as Giraud, after he had finished the "OK Corral" cycle in 2005, no longer continued to produce comics and/or art on a commercial base, but rather on a personal base, usually under the aegis of his own publishing house Mœbius Production.

As Mœbius Production, Giraud published from 2000 to 2010 Inside Mœbius (French text despite English title), an illustrated autobiographical fantasy in six hardcover volumes totaling 700 pages.[8] Pirandello-like, he appears in cartoon form as both creator and protagonist trapped within the story alongside his younger self and several longtime characters such as Blueberry, Arzak (the latest re-spelling of the Arzach character's name), Major Grubert (from The Airtight Garage) and others.

Jean Giraud drew the first of the two-part volume of the XIII series titled La Version Irlandaise ("The Irish Version") from a script by Jean Van Hamme,[129] to accompany the second part by the regular team Jean Van Hamme–William Vance, Le dernier round ("The Last Round"). Both parts were published on the same date (13 November 2007)[130] and were the last ones written by Van Hamme before Yves Sentes took over the series.[131] The contribution was also a professional courtesy to the series' artist, Vance, who had previously provided the artwork for the first two titles in the by Giraud written Marshall Blueberry spin-off series.

Late in life, Giraud also decided to revive his seminal Arzak character in an elaborate new adventure series; the first (and last in hindsight) volume of a planned trilogy, Arzak l'arpenteur, appeared in 2010.[132] He also added to the Airtight Garage series with two volumes entitled "Le chasseur déprime" (2008[133]) and "Major" (2011[134]), as well as the art book "La faune de Mars" (2011[135]), the latter two initially released in a limited, 1000 copy French only, print run by Mœbius Production. By this time, Giraud created his comic art on a specialized graphic computer tablet, as its enlargement features had become an indispensable aid, because of his failing eyesight.

Creating comics became increasingly difficult for Giraud, as his eyesight started to fail him in his last years, having undergone severe surgery in 2010 to stave off blindness in his left eye, and it was mainly for this reason that Giraud increasingly concentrated on creating single-piece art, both as "Gir" and as "Mœbius", on larger canvases on either commission basis or under the aegis of Mœbius Production.[136] Much of the latter artwork was from 2005 onward, alongside older original art Giraud still had in his possession, sold by the company for considerable prices in specialized comic auctions at such auction houses like Artcurial,[137] Hôtel Drouot[138] and Millon & Associés.[139]

Illustrator and author

As already indicated above, Giraud had throughout his entire career made illustrations for books, magazines and music productions[30] (though playing the piano and electric guitar, Giraud was, unlike his second son Raphaël, regrettably not a creative musician himself by his own admission, but did have a lifelong fascination with Jazz[140]), illustrating for example the 1987 first edition of the science fiction novel Project Pendulum by Robert Silverberg,[141] and the 1994 French edition[142] of the novel The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho. The subsequent year Giraud followed up in the same vein as the Coelho novel, with his cover and interior illustrations for a French 1995 reprint of "Ballades" from the French medieval poet François Villon.[143]

An out-of-the-ordinary latter-day contribution as such, constituted his illustrations as "Mœbius" for the Thursday March 6, 2008 issue of the Belgian newspaper Le Soir. His illustrations accompanied news articles throughout the newspaper, providing a Mœbiusienne look on events. In return, the newspaper, for the occasion entitled "Le Soir par (by) Mœbius", featured two half-page editorials on the artist (pp. 20 & 37).

Under the names Giraud, Gir and Mœbius, he also wrote several comics for other comic artists as listed below, and the early ones including Jacques Tardi.[144] and fr:Claude Auclair[145] Aside from writing for other comic artists, he also wrote story outlines for the movies Les Maîtres du temps, Internal Transfer, Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland and Thru the Moebius Strip as outlined further down the line.

As author on personal title, Giraud has – apart from his own bande dessinée scripts – written philosophical poetry that accompanied his art in his Mœbius artbooks of the 1980s and 1990s. He also wrote the "Story Notes" editorials for the American Epic publications, providing background information on his work contained therein. In 1998, he took time off to write his Moebius-Giraud: Histoire de mon double autobiography.[146]

Films

"Tron was not a big hit. The movie went out in theaters in the same week as E.T. and, oh, that was a disaster for it. There was also Blade Runner and Star Trek [The Wrath of Khan] that summer so it was a battle of giants. Tron was a piece of energy trying to survive. It is still alive. It survives. And the new movie is what Steven wanted to do back then but at that time CG was very odd and we were pioneers. I almost did the first computer-animated feature after that, it was called Star Watcher, we had the story, we had the preparation done, we were ready to start. But it came apart; the company did not give us the approval. It was too far, the concept to do everything in computer animation. We were waiting, waiting, and then our producer died in a car accident. Everything collapsed. That was my third contribution to animation and my worst experience. [Les Maîtres du Temps] is a strange story, it’s a small movie, and cheap — incredibly cheap –it was more than independent. When I saw the film for the first time I was ashamed. It’s not a Disney movie, definitely. But because the movie has, maybe a flavor, a charm, it is still alive after all that time. More than 35 years now and it is still here."

Giraud's friend Jean-Claude Mézières has divulged in the 1970s that their very first outing into the world of cinema concerned a 1957 animated Western, unsurprisingly considering their shared passion for the genre, "Giraud, with his newfound prestige because of his trip to Mexico, started a pro career at Cœurs Valiants, but together with two other friends we tackled a very ambitious project first: a cartoon western for which Giraud drew the sets and the main characters. Alas, rather disappointingly, we had to stop after only 45 seconds!"[147] Any further movie aspirations Giraud, who himself had considered the effort "too laborious",[148] might have had entertained had to wait until he received the 1974 invitation of Alejandro Jodorowsky to work on his planned adaptation of Frank Herbert's Dune, which was however abandoned in pre-production.[149] Jodorowsky's Dune, a 2013 American-French documentary directed by Frank Pavich, explores Jodorowsky's unsuccessful attempt. Giraud, a non-English speaker at the time, has later admitted that the prospect of moving over to Los Angeles filled him with trepidations at the time, causing him to procrastinate initially. It was friend Philippe Druilet (with whom he would co-found Les Humanoïdes Associés later that year) who pushed him to up and go, which he did by going AWOL again from his job at Pilote. Giraud was grateful for Druillet pushing him as he found that he reveled in his first Hollywood experience.[148] In the end the project took nine months before it fell apart, but Giraud's presence was not always required, giving him ample time to return to France on several occasions, to pursue his other work, such as his work for L'Écho des savanes and, most importantly, to firstly finish up on Blueberry's "Nez Cassé", which he ultimately did in record time, this time formally quitting Pilote afterwards.[51]

Despite Jodowowsky's project falling through, it had attracted the attention of other movie makers. One of them was Ridley Scott who managed to reassemble a large part of Jodorowsky's original creative team, including Giraud, for his 1979 science fiction thriller Alien. Hired as a concept artist, Giraud's stay on the movie lasted only a few days, as he had obligations elsewhere. Nonetheless, his designs for the Nostromo crew attire, and their spacesuits in particular, were almost one-on-one adopted by Scott and appearing onscreen as designed,[150] resulting in what Giraud had coined "two weeks of work and ten years of fallout in media and advertising".[148] Scott did explicitly acknowledge "Mœbius" for his contributions in the special features for the movie in the Alien Quadrilogy home media collection. Scott was taken with Giraud's art, having cited "The Long Tomorrow" as an influence on his second major movie Blade Runner of 1982 (see below), and invited him again for both this, and his subsequent third major movie Legend of 1985, which Giraud had to decline in both cases for, again, obligations elsewhere. He especially regretted not having been able to work on the latter movie, having deemed it "very good".[148]

.jpg)

1981 saw the release of the animated film Heavy Metal from of Ivan Reitman. The heavily "Arzach"-inspired last, "Taarna", section of the movie, has led to the persistent misconception, especially held in the United States, that Giraud had provided characters and situations for the segment, albeit uncredited.[151] Giraud however, had already emphatically squashed that particular misconception himself on an early occasion, "I had absolutely nothing to do with it," stated the artist in 1982, "Sure, the people who made the movie were inspired by quite a few things from "Arzach"," further explaining that, while the American producers had indeed intended to use the artist's material from the eponymous magazine, there were legalities involved between the American and French mother magazines, because the latter had financial interests in Laloux's below mentioned Les Maîtres du temps that was concurrently in development. The American producers went ahead regardless of the agreements made between them and Métal hurlant. While not particularly pleased with the fact, Giraud was amused when third parties wanted to sue the Americans on his behalf. Giraud however, managed to convince his editor-in-chief Jean-Pierre Dionnet (one of his co-founding friends of Métal hurlant) to let the issue slide, as he found "all that fuss with lawyers" not worth his while, aside from the incongruous circumstance that the French magazine was running advertisements for the American movie.[152]

Still, Alien led to two other movie assignments, this time as both concept and storyboard artist, 1982. The first one concerned the Disney science fiction movie Tron, whose director Steven Lisberger specifically requested Giraud, after he had discovered his work in Heavy Metal.[148] The second assignment concerned Giraud's collaboration with director René Laloux to create the science fiction feature-length animated movie Les Maîtres du temps (released in English as Time Masters) based on a novel by Stefan Wul. He and director Rene Laloux shared the award for Best Children's Film at the Fantafestival that year.[151] For the latter, Giraud was also responsible for the poster art and the comic adaption of the same title, with some of his concept and storyboard art featured in a "making-of" book to boot.[153] Excepting Les Maîtres du temps, Giraud's movie work had him travel to Los Angeles for longer periods of time.

Outside his actual involvement with motion pictures, Giraud was in this period of time also occasionally commissioned to create poster art for, predominantly European, movies. Movies for which Giraud, also as "Mœbius", created poster art included, Touche pas à la femme blanche ! (1974 as Gir, three 120x160 cm versions), S*P*Y*S (1974, unsigned, American movie but poster art for release in France), fr:Vous ne l'emporterez pas au paradis (1975, unsigned), Les Chiens (1979 as Mœbius, rejected, used as cover for Taboo 4), Tusk (1980 as Giraud, a Jodorowsky film), and fr:La Trace (1983 as Mœbius).

As his two 1982 movies coincided with the end of his Métal hurlant days and his departure for Tahiti shortly thereafter, this era can be seen as Giraud's "first Hollywood period", especially since the next project he embarked on entailed a movie in which he was very much invested as initiator, writer and producer as well, contrary to the movies he hitherto had worked upon as a gun-for-hire.

While Giraud was residing in Appel-Guéry's commune, he, together with Appel-Guéry and another member of the commune, Paula Salomon, came up with a story premise for a major animated science fiction movie called Internal Transfer, which was endowed with the English title Starwatcher – after which Giraud's American publishing house was named. Slated for the production was Arnie Wong, whom Giraud had met during the production of Tron (and, incidentally, one of the animators of the vaunted "Taarna" segment of the Heavy Metal movie[154]), and it was actually Disney whom Giraud offered the production first. Disney, at the time not believing in the viability of such a production in animation, declined. Another member of the commune fronted some of the money for the project to proceed, and the production was moved to Wong's animation studio in Los Angeles. It was this circumstance that provided Giraud with his alibi to leave Appel-Guéry's commune and settle in California. Much to Giraud's disappointment and frustration though, the project eventually fell apart for several extraneous reasons, most notably for lack of funding, as related above by the artist.[148] Still, the concept art he provided for the project served as the basis for his first collaboration with Geoff Darrow, whom he had met previously on the production of Tron, on their 1985 City of Fire art portfolio. Some of the concept art was reprinted in the art book "Made in L.A.".[71]

Yet, despite this failure to launch, it did lead to his, what can be considered, "second Hollywood period" in his "American period". Concurrent with his career as a comic artist in the United States, invitations followed to participate as concept artist on Masters of the Universe (1987), Willow (1988), The Abyss (1989), and finally Yutaka Fujioka's Japanese animated feature film Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland (1989), for which he was not only the conceptual designer, but also the story writer. It was for this movie that Giraud resided in Japan for an extended period of time.[151][148] Giraud followed up on his involvement with Little Nemo by writing the first two outings of the 1994-2000 French graphic novel series of the same name, drawn by fr:Bruno Marchand.[155]

His definitive return to France in 1989 marked the beginning of Giraud's third and last movie period. Giraud made original character designs and did visual development for Warner Bros. partly animated 1996 movie Space Jam. 1997 saw his participation as concept artist on Luc Besson's science fiction epic The Fifth Element, which was of great personal importance for Giraud as it meant working together with his lifelong friend Jean-Claude Mézières, coming full circle after their very first 1957 attempt at creating a motion picture. The 2005 documentary made for this occasion was testament to the great friendship both men had for each other. Concurrently, Giraud's oldest child, daughter Hélène, was employed on the movie in a similar function, albeit uncredited, though Giraud had stated with fatherly pride, "Yes, she had cooperated in a truly engaged manner. She started at the crack of dawn, and only went home in the evening, after the whole team had stopped working."[156] Giraud's experience on the movie was however marred by the 2004 lawsuit he and Alejandro Jodorowsky leveled against Besson for alleged plagiarism of L'Incal, a lawsuit they lost.[157]

2005 saw the release of the Chinese movie Thru the Moebius Strip, based on a story by Giraud who also served as the production designer and the co-producer, and which reunited him with Arnie Wong, whereas his stint as concept designer on the 2012 animated science fiction movie Strange Frame, has become Giraud's final recorded motion picture contribution.[158]

Movie adaptations

In 1991 his graphic novel short, "Cauchemar Blanc", was cinematized by Matthieu Kassovitz, winning Kassovitz (but not Giraud) two film awards.[159] With fr:Arzak Rhapsody, Giraud saw his ambitions as a full-fledged animation movie maker at least in part fulfilled. A 2002 series for French television broadcaster France 2, it consisted of fourteen four minute long animated vignettes, based on Giraud's seminal character, for which he did the writing, drawings and co-production. Young daughter Nausicaa had voice-over appearances in three of the episodes together with her father.[160]

The Blueberry series was adapted for the screen in 2004, by Jan Kounen, as Blueberry: L'expérience secrète. Two previous attempts to bring Blueberry to the silver screen in the 1980s had fallen through; American actor Martin Kove had actually already been signed to play the titular role for one of the attempts.[161]

2010 saw the adaptation of "La planète encore" ("The Still Planet"), a short story from the Le Monde d'Edena universe – and which had won him his 1991 Eisner Award – into an animated short. Moebius Production served as a production company, with Isabelle Giraud serving as one of its producers. Giraud himself was one of the two directors of the short and it premiered at the «Mœbius transe forme» exposition at the Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain in Paris.[162]

Exhibitions

Part of the "many desires" that increasingly attracted Giraud in his later days, steering him away from creating traditional bandes dessinées, was his personal fascination and involvement with the many exhibitions dedicated to his work, that started to proliferate from the mid-1990s onward not only in native France, but internationally as well, causing him to frequently travel abroad, among others to Japan, for extended periods of time, with the 2010 «Mœbius transe forme» exposition in Paris becoming the apotheosis.[163]

-

Summer 1991: Exposition at the fr:Maison de la culture Frontenac, Montréal

Summer 1991: Exposition at the fr:Maison de la culture Frontenac, Montréal -

26 April-16 August 1995:«Mœbius: a retrospective» exposition at the Cartoon Art Museum, San Francisco, came with limited edition catalog (see below)

26 April-16 August 1995:«Mœbius: a retrospective» exposition at the Cartoon Art Museum, San Francisco, came with limited edition catalog (see below) -

December 1995: «Wanted: Blueberry» exposition at the Arthaud Grenette mega-bookstore, Grenoble, also featuring original Blueberry art by Colin Wilson. Both he and Jean Giraud attended the opening on 1 December, making themselves also available for book signings. Prior to the opening a promotional leaflet was disseminated by the bookstore ("Arthaud BD News", issue 1, November 1995), featuring a three-page interview with Giraud.[164]

December 1995: «Wanted: Blueberry» exposition at the Arthaud Grenette mega-bookstore, Grenoble, also featuring original Blueberry art by Colin Wilson. Both he and Jean Giraud attended the opening on 1 December, making themselves also available for book signings. Prior to the opening a promotional leaflet was disseminated by the bookstore ("Arthaud BD News", issue 1, November 1995), featuring a three-page interview with Giraud.[164] -

19 September-9 October 1996: «Jean Giraud Blueberry» exposition at the Stardom Gallery, Paris, for the occasion of the upcoming release of the "Blueberry's" artbook by Stardom[120] – Giraud's own publishing house/art gallery. The below-mentioned 1997 documentary was the registration of events surrounding the release, including the exhibition.

19 September-9 October 1996: «Jean Giraud Blueberry» exposition at the Stardom Gallery, Paris, for the occasion of the upcoming release of the "Blueberry's" artbook by Stardom[120] – Giraud's own publishing house/art gallery. The below-mentioned 1997 documentary was the registration of events surrounding the release, including the exhibition. -

August 1997: «Giraud/Mœbius» themed Festival BD de Solliès-Ville, co-produced with Stardom.[165] A special festival guide, illustrated by Giraud – having received the festival's most prestigious comic award the previous year – and featuring a large interview with the artist, was published for the occasion by the festival organization.[166]

August 1997: «Giraud/Mœbius» themed Festival BD de Solliès-Ville, co-produced with Stardom.[165] A special festival guide, illustrated by Giraud – having received the festival's most prestigious comic award the previous year – and featuring a large interview with the artist, was published for the occasion by the festival organization.[166] -

October–November 1997: Grande exposition, Palermo

October–November 1997: Grande exposition, Palermo -

November 1997-January 1998: Grande exposition, Milan

November 1997-January 1998: Grande exposition, Milan -

February–March 1998: Grande exposition, Venice

February–March 1998: Grande exposition, Venice -

December 1998-January 1990: Musée d'art contemporain de Lyon

December 1998-January 1990: Musée d'art contemporain de Lyon -

1999: Exposition at Fondation Cartier, Paris

1999: Exposition at Fondation Cartier, Paris -

26 January-3 September 2000: «Trait de Génie Giraud» exposition, fr:Centre national de la bande dessinée et de l'image, Angoulême

26 January-3 September 2000: «Trait de Génie Giraud» exposition, fr:Centre national de la bande dessinée et de l'image, Angoulême -

October 2001: Grande exposition, Montrouge

October 2001: Grande exposition, Montrouge -

May–June 2000: Große Austellung, Erlangen

May–June 2000: Große Austellung, Erlangen -

May 2000: Collective exposition on contemporary comics at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

May 2000: Collective exposition on contemporary comics at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris -

June 2003: Great exposition, Kemi

June 2003: Great exposition, Kemi -

.svg.png) 16 November-31 December 2003: «Giraud-Moebius» exposition, Grand Manège Caserne Fonck, Liège

16 November-31 December 2003: «Giraud-Moebius» exposition, Grand Manège Caserne Fonck, Liège -

January–February 2003: Große Austellung in the Museum für Neue Kunst, Karlsruhe

January–February 2003: Große Austellung in the Museum für Neue Kunst, Karlsruhe -

December 2004-April 2005: «Giraud/Mœbius & Hayao Miyazaki» exposition at the Musée de la Monnaie de Paris[167]

December 2004-April 2005: «Giraud/Mœbius & Hayao Miyazaki» exposition at the Musée de la Monnaie de Paris[167] -

June 2005: Exposition «Mythes Grecs» at the Stardom/Mœbius Production Art Gallery, Paris

June 2005: Exposition «Mythes Grecs» at the Stardom/Mœbius Production Art Gallery, Paris -

December 2005: «Jardins d’Eros» exposition at the Stardom/Mœbius Production Art Gallery, Paris

December 2005: «Jardins d’Eros» exposition at the Stardom/Mœbius Production Art Gallery, Paris -

February 2006: Exposition "sur le thème du Rêve" at the Centre d'arts plastiques contemporains de Bordeaux

February 2006: Exposition "sur le thème du Rêve" at the Centre d'arts plastiques contemporains de Bordeaux -

Octobre 2006: «Boudha line» exposition at the Stardom/Mœbius Production Art Gallery, Paris

Octobre 2006: «Boudha line» exposition at the Stardom/Mœbius Production Art Gallery, Paris -

May 2007: Exposition, Seoul

May 2007: Exposition, Seoul -

May 2007: «Hommage au Major» exposition at the Stardom/Mœbius Production Art Gallery, Paris

May 2007: «Hommage au Major» exposition at the Stardom/Mœbius Production Art Gallery, Paris -

February 2008: «La citadelle du vertige» attraction from Futuroscope, (Poitiers), inspired by the Garage hermétique universe.

February 2008: «La citadelle du vertige» attraction from Futuroscope, (Poitiers), inspired by the Garage hermétique universe. -

June 2008: «Fou et Cavalier» exposition at l'Espace Cortambert/Mœbius Production, Paris

June 2008: «Fou et Cavalier» exposition at l'Espace Cortambert/Mœbius Production, Paris -

.svg.png) 15 January-14 June 2009: «Blueberry» exposition at the Maison de la bande dessinée, Bruxelles[168]

15 January-14 June 2009: «Blueberry» exposition at the Maison de la bande dessinée, Bruxelles[168] -

May 2009: Exposition at the Kyoto International Manga Museum

May 2009: Exposition at the Kyoto International Manga Museum -

November 2009: «Arzak, destination Tassili» exposition at the SFL building located at 103 rue de Grenelle, Paris (Co-production of Espace Cortambert/SFL/Mœbius Production)

November 2009: «Arzak, destination Tassili» exposition at the SFL building located at 103 rue de Grenelle, Paris (Co-production of Espace Cortambert/SFL/Mœbius Production) -

12 October 2010 – 13 March 2011: «Mœbius transe forme» exposition at the Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain, Paris, which the museum had called "the first major exhibition in Paris devoted to the work of Jean Giraud, known by his pseudonyms Gir and Mœbius."[169] A major and prestigious event, it reflected the status Giraud had by then attained in French (comic) culture. A massive, limited edition deluxe art book was released by the museum for the occasion.[170]

12 October 2010 – 13 March 2011: «Mœbius transe forme» exposition at the Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain, Paris, which the museum had called "the first major exhibition in Paris devoted to the work of Jean Giraud, known by his pseudonyms Gir and Mœbius."[169] A major and prestigious event, it reflected the status Giraud had by then attained in French (comic) culture. A massive, limited edition deluxe art book was released by the museum for the occasion.[170] -

June–December 2011: «Mœbius multiple(s)» exposition at the Musée Thomas-Henry, Cherbourg-Octeville

June–December 2011: «Mœbius multiple(s)» exposition at the Musée Thomas-Henry, Cherbourg-Octeville

Stamps

In 1988 Giraud was chosen, among 11 other winners of the prestigious Grand Prix of the Angoulême Festival, to illustrate a postage stamp set issued on the theme of communication.[171]

Style

Giraud's working methods were various and adaptable ranging from etchings, white and black illustrations, to work in colour of the ligne claire genre and water colours.[172] Giraud's solo Blueberry works were sometimes criticized by fans of the series because the artist dramatically changed the tone of the series as well as the graphic style.[173] However, Blueberry's early success was also due to Giraud's innovations, as he did not content himself with following earlier styles, an important aspect of his development as an artist.[174]

To distinguish between work by Giraud and Moebius, Giraud used a brush for his own work and a pen when he signed his work as Moebius. Giraud was known for being an astonishingly fast draftsman.[175]

His style has been compared to the Nouveaux réalistes, exemplified in his turn from the bowdlerized realism of Hergé's Tintin towards a grittier style depicting sex, violence and moral bankruptcy.[2]