Javakheti

| Javakheti | |

|---|---|

| Historical region | |

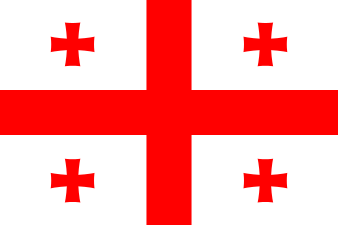

Map highlighting the historical region of Javakheti in Georgia | |

| Largest city | Akhalkalaki |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,588 km2 (999 sq mi) |

| Elevation(highest point: Didi Abuli) | 3,300 m (10,800 ft) |

| Population (2014)[1] | |

| • Total | 69,561 |

| • Density | 27/km2 (70/sq mi) |

Javakheti (Georgian: ჯავახეთი [dʒɑvɑχɛtʰi]; Armenian: Ջավախք, Javakhk)[2][3] is a historical province in southern Georgia, corresponding to the modern Akhalkalaki and Ninotsminda municipalities. Historically, Javakheti borders in the west to the Kura River (Mtkvari), and in the north, south and east with the Shavsheti, Samsari and Nialiskuri mountains. Principal economic activities in this region are subsistence agriculture, particularly potatoes, and raising livestock.

In 1995, the Akhalkalaki and Ninotsminda districts, comprising the historical territory of Javakheti, was merged with the neighboring land of Samtskhe to form a new administrative region, Samtskhe-Javakheti. Armenians comprise the majority of Javakheti's population. According to the 2014 Georgian census, of the 41,870 inhabitants in Akhalkalaki Municipality (93%) and Ninotsminda Municipality 23,262 (95%) were Armenians.[1]

Etymology

In terminology, the name Javakheti is taken from javakh core with traditional Georgian –eti suffix; commonly, Javakheti means the home of Javakhs (an ethnic subgroup of Georgians), as for example, the word Ossetia is taken from Georgian Osi plus -eti. The -k suffix in Armenian has an identical meaning.

The earliest mention of the name was found in Urartu sources, in the notes of king Argishti I of Urartu, 785 BC, as Zabaha.[4]

History

Antiquity

In the sources, the region was recorded as Zabakha in 785 BC, by the king Argishti I of Urartu (Ararat Kingdom). According to the kartlis tskhovreba, provinces of the Iberian (Kartlian) kingdom were: Gachiani and Gardabani, that is, of the historical region of Georgia—Kvemo (Lower) Kartli.[5] According to Strabo, Armenia, though a small country in earlier times, was enlarged by Artaxias and Zariadris.[6] After Urartu Javakhk became a part of the Gugark province of Great Armenia, and remained as a part of Armenia until the end of Arshakid dynasty rule in 428 AC.[7] In the 1st century AD king of Kartli (Georgian Kingdom) Parsman I (Kveli) managed to gain control over Javakheti.

One of the earliest Armenian sources, Faustus of Byzantium (the 5th century) writes: “Maskut King Sanesan, extremely angry, was filled with hate for his tribesman, Armenian King Khosrow, and gathered all of his troops—Huns, Pokhs, Tavaspars, Khechmataks, Izhmakhs, Gats, Gluars, Gugars, Shichbs, Chilbs, Balasich, and Egersvans, as well as an uncountable number of other diverse nomadic tribes, all the numerous troops he commanded. He crossed his border, the great River Kura, and invaded the Armenian country.”[8]

In the 5th century during the ruling of Vakhtang V (Gorgaslani) Javakheti was a province of Iberia and after his death his second wife the Byzantine princess settled in Tsunda (part of Javakheti).

Armenian scientist of the 10th century Ukhtanes talks about the family tree of Kyrion, the Catholicos of Georgia. The literal translation of this text is as follows: Kyrion “came from the Georgians in terms of country and lineage, from the region of the Javakhs.”There can be no doubt that Ukhtanes believed Javakheti to be part of Georgia (Iberia), and the Javakhs to be Georgians. Z. Aleksidze examines the viewpoint of this historian and the enlightened Armenian society of the 10th century on the problem that interests us in depth.[9]

When relating about his ancestors, 13th century Armenian historian Stepanos Orbelian states that they received many estates from the rulers of Kartli (Georgia), including the fortress of Orbeti, “settled in the borough of Orbeti and, after a long time, were called Orbuls, that is, Orbets, after the name of this fortress, since this tribe (that is, Georgians.—D.M.) had the custom of naming its princes after the place they lived, for example, Eristavs from (the region) Ereti, Javakhurs from Javakheti, Kakhetian from Kakheti … and many more.”

Javakheti was an important part of the Kingdom of Kartli. In the 11th century Akhalkalaki became the center of upper Javakheti, and Tmogvi the center of lower Javakheti. Under the Georgian Kingdom (11th-13th centuries), Javakheti bridges, churches, monasteries, and royal residences (Lgivi, Ghrtila, Bozhano, Vardzia) were constructed. From the 13th century, Javakheti included the territories of Palakatsio and part of Meskheti. In the 15th century, Javakheti was governed by Samtskhe-Saabatago.

Historical Javakheti was divided as Upper Javakheti (Akhalkalaki plateau) and Lowland Javakheti (with the canyon on the left side of the Mtkvari River).

Middle Ages

From the 11th century, the center of upper Javakheti became Akhalkalaki. From the 10th century, the center of lowland Javakheti was Tmogvi. In the centuries of rise of the Georgian kingdom (11th-13th centuries), Javakheti was also in the uprising period: bridges, churches, monasteries, and royal residences (Lgivi, Ghrtila, Bozhano, Vardzia) were built. From the 12th century, the domain was ruled by representatives of the feudal family of Toreli.

From the 13th century, the administrative borders of the region combined in addition Palakatsio (modern Turkey) and part of Samtskhe. In the 15th century, Javakheti was part of the principality of Samtskhe-Saatabago. In the 16th century, the region, as well as the adjacent territories of western Georgia, was occupied by the Ottoman Empire. The Georgian population of Javakheti was displaced to inner regions of Georgia such as Imereti and Kartli. Those who remained gradually became Muslim.

Russian Empire

In the first third of the 19th century, following the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813) and the Russo-Persian War of 1826-1828, Russia conquered the Southern Caucasus, and the whole of Georgia, along with the rest of the Caucasus, was incorporated within the Russian Empire. At that time Javakheti was inhabited by Georgian Muslims and after Russian conquest they mostly migrated to the Ottoman Empire.[10] After Russian encouragement the area was resettled by Christian Ottoman Armenians.[10] In 1828, because of luck, the Russian army in battle with the Turks made the decision real to move people to Samtskhe-Javakheti. Trialeti and Javakheti was filled with Christian Armenians and Caucasus Greeks.[11] In the early 20th century, a large number of Armenian refugees from the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire, and Doukhobor sect members of Russian Empire, settled the region.

On December 3, 1829, General Ivan Paskevich created a special committee for relocation with chairmanship of governor Piotr Zaveleisky (Russian: П. Д. Завелейский).[12] The committee was created for the act for relocation. Аccording to preliminary calculations, the committee planned to displace 8,000 families from Kars, Erzurum and Doğubeyazıt, but after a short time, the number was increased to 14,000.

The political target of Tsarist Russia was to get ethnical colours in Georgia, while the king-loving Georgian people were not very happy with Russian rule. Because of this, some people refused to move Meskhetians from Imereti back to their homes in freed places of Javakheti and other southern regions.

After an offensive on Akhaltsikhe, the sons of Mesketian families of the 16th-17th centuries (Tsitsishvili, Avalishvili, Muskhelishvili and others) got to Ivan Paskevich and requested the return of legitimate lands on according to conservated sigheles issued by Georgian kings. Paskevich refused their request with some regrets.

Soviet era

Georgia came fully under Soviet control in 1921,and Javakheti,along with other former Georgian territories, became part of the Georgian SSR. The remaining Muslim minority in Javakheti, also known as "Meskhetian Turks", were deported to Uzbekistan in 1944 during the regime of Stalin.[10]

Republic of Georgia

Currently Armenians form the ethnic majority in the region.[13] Since independence many Doukhobor have left for Russia.[10]

Current situation

An expected improvement is the planned construction of the highway (financed by the US Millennium Challenge Account) to more effectively link the region with the rest of Georgia. Also, a railroad is planned to run from Kars, Turkey to Baku, Azerbaijan via the area (see: Kars Baku Tbilisi railway line), but the Armenian population of Javakheti are opposed to this rail link because it excludes and isolates Armenia. There is already another railroad linking Armenia, Georgia and Turkey, which is the Kars-Gyumri-Akhalkalaki railroad line. The existing line is in working condition and could be operational within weeks, but due to the Turkish blockade of Armenia since 1993, the railroad is not operational.

See also

References

- 1 2 "Population Census 2014". www.geostat.ge. National Statistics Office of Georgia. November 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ Rezvani, Babak (2014). Conflict and Peace in Central Eurasia: Towards Explanations and Understandings. BRILL. p. 1. ISBN 9789004276369.

...Javakheti (called Javakhk by Armenians).

- ↑ "Georgian Court Sentences Armenian Activist To 10 Years In Prison". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 8 April 2009.

...Georgian region of Javakheti (Armenian Javakhk)...

- ↑ Melkonyan, Ashot (2007). Javakhk in the 19th century and the 1st quarter of the 20th century : a historical research. Erevan: National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia, Institute of History. p. 36. ISBN 9994173073.

- ↑ Kartlis tskhovreba (History of Georgia), Tbilisi, 2008, p. 16

- ↑ http://www.soltdm.com/sources/mss/strab/11.htm

- ↑ «Джавахк», Краткая армянская энциклопедия, т. 4, издательство «Армянская энциклопедия» Ереван, 2003 г., стр. 226

- ↑ ИСТОРИЯ АРМЕНИИ [History of Armenia] (in Russian). Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Academy of Sciences of Armenian SSR. 1953.

- ↑ http://www.ca-c.org/c-g/2011/journal_eng/c-g-1-2/13.shtml#nazad43

- 1 2 3 4 Moshe Gammer (25 June 2004). The Caspian Region, Volume 2: The Caucasus. Routledge. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-1-135-77541-4.

- ↑ Boeschoten, Hendrik; Rentzsch, Julian (2010). Turcology in Mainz. p. 142. ISBN 978-3-447-06113-1. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ↑ Migration of Armenians (Russian).

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20110708124400/http://www.caucaz.com/home_eng/breve_contenu.php?id=235. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Bibliography

- Lalayan, Yervand (1895). Ջաւախք [Javakhk'] (in Armenian). Azgagrakan Handes [Ethnographic Review].

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Javakheti. |

Coordinates: 41°24′00″N 43°30′00″E / 41.4000°N 43.5000°E