Yakuza

"Yakuza" written in katakana | |

| Founded |

17th century (presumed to have originated from the Kabukimono) |

|---|---|

| Membership | 102,560 members[1] |

| Criminal activities | Criminal activities and/or illegitimate businesses |

| Notable members |

Principal clans |

Yakuza (ヤクザ, [jaꜜkɯza]), also known as gokudō (極道, "the ultimate path"), are members of transnational organized crime syndicates originating in Japan. The Japanese police, and media by request of the police, call them bōryokudan (暴力団, "violent groups"), while the yakuza call themselves "ninkyō dantai" (任侠団体 or 仁侠団体, "chivalrous organizations"). The yakuza are notorious for their strict codes of conduct and organized fiefdom-nature. They have a large presence in the Japanese media and operate internationally with an estimated 102,000 members.[2]

Divisions of origin

Despite uncertainty about the single origin of yakuza organizations, most modern yakuza derive from two classifications which emerged in the mid-Edo period (1603–1868): tekiya, those who primarily peddled illicit, stolen or shoddy goods; and bakuto, those who were involved in or participated in gambling.[3]

"Tekiya" (peddlers) were considered one of the lowest social groups in Edo. As they began to form organizations of their own, they took over some administrative duties relating to commerce, such as stall allocation and protection of their commercial activities. During Shinto festivals, these peddlers opened stalls and some members were hired to act as security. Each peddler paid rent in exchange for a stall assignment and protection during the fair.

The Edo government eventually formally recognized such tekiya organizations and granted the oyabun (leaders) of tekiya a surname as well as permission to carry a sword—the wakizashi, or short samurai sword (the right to carry the katana, or full-sized samurai swords, remained the exclusive right of the nobility and samurai castes). This was a major step forward for the traders, as formerly only samurai and noblemen were allowed to carry swords.

Bakuto (gamblers) had a much lower social standing even than traders, as gambling was illegal. Many small gambling houses cropped up in abandoned temples or shrines at the edge of towns and villages all over Japan. Most of these gambling houses ran loan sharking businesses for clients, and they usually maintained their own security personnel. The places themselves, as well as the bakuto, were regarded with disdain by society at large, and much of the undesirable image of the yakuza originates from bakuto; this includes the name yakuza itself (ya-ku-za, or 8-9-3, is a losing hand in Oicho-Kabu, a form of Baccarat).

Because of the economic situation during the mid-period and the predominance of the merchant class, developing yakuza groups were composed of misfits and delinquents that had joined or formed yakuza groups to extort customers in local markets by selling fake or shoddy goods.[3]

The roots of the yakuza can still be seen today in initiation ceremonies, which incorporate tekiya or bakuto rituals. Although the modern yakuza has diversified, some gangs still identify with one group or the other; for example, a gang whose primary source of income is illegal gambling may refer to themselves as bakuto.

Organization and activities

Structure

During the formation of the yakuza, they adopted the traditional Japanese hierarchical structure of oyabun-kobun where kobun (子分; lit. foster child) owe their allegiance to the oyabun (親分, lit. foster parent). In a much later period, the code of jingi (仁義, justice and duty) was developed where loyalty and respect are a way of life.

The oyabun-kobun relationship is formalized by ceremonial sharing of sake from a single cup. This ritual is not exclusive to the yakuza—it is also commonly performed in traditional Japanese Shinto weddings, and may have been a part of sworn brotherhood relationships.[4]

During the World War II period in Japan, the more traditional tekiya/bakuto form of organization declined as the entire population was mobilised to participate in the war effort and society came under strict military government. However, after the war, the yakuza adapted again.

Prospective yakuza come from all walks of life. The most romantic tales tell how yakuza accept sons who have been abandoned or exiled by their parents. Many yakuza start out in junior high school or high school as common street thugs or members of bōsōzoku gangs. Perhaps because of its lower socio-economic status, numerous yakuza members come from Burakumin and ethnic Korean backgrounds.

Yakuza groups are headed by an oyabun or kumichō (組長, family head) who gives orders to his subordinates, the kobun. In this respect, the organization is a variation of the traditional Japanese senpai-kōhai (senior-junior) model. Members of yakuza gangs cut their family ties and transfer their loyalty to the gang boss. They refer to each other as family members - fathers and elder and younger brothers. The yakuza is populated almost entirely by men, and there are very few women involved who are called ane-san (姐さん, older sister). When the 3rd Yamaguchi-gumi boss (Kazuo Taoka) died in the early 1980s, his wife (Fumiko) took over as boss of Yamaguchi-gumi, albeit for a short time.

Yakuza have a complex organizational structure. There is an overall boss of the syndicate, the kumicho, and directly beneath him are the saiko komon (senior advisor) and so-honbucho (headquarters chief). The second in the chain of command is the wakagashira, who governs several gangs in a region with the help of a fuku-honbucho who is himself responsible for several gangs. The regional gangs themselves are governed by their local boss, the shateigashira.[5]

Each member's connection is ranked by the hierarchy of sakazuki (sake sharing). Kumicho are at the top, and control various saikō-komon (最高顧問, senior advisors). The saikō-komon control their own turfs in different areas or cities. They have their own underlings, including other underbosses, advisors, accountants and enforcers.

Those who have received sake from oyabun are part of the immediate family and ranked in terms of elder or younger brothers. However, each kobun, in turn, can offer sakazuki as oyabun to his underling to form an affiliated organisation, which might in turn form lower ranked organizations. In the Yamaguchi-gumi, which controls some 2,500 businesses and 500 yakuza groups, there are fifth rank subsidiary organizations.

Rituals

_-_Tattooed_japanese_men_-_ca._1870.jpg)

Yubitsume, or the cutting off of one's finger, is a form of penance or apology. Upon a first offense, the transgressor must cut off the tip of his left little finger and give the severed portion to his boss. Sometimes an underboss may do this in penance to the oyabun if he wants to spare a member of his own gang from further retaliation. This practice has started to wane amongst the younger members, due to it being an easy identifier for police.[6]

Its origin stems from the traditional way of holding a Japanese sword. The bottom three fingers of each hand are used to grip the sword tightly, with the thumb and index fingers slightly loose. The removal of digits starting with the little finger moving up the hand to the index finger progressively weakens a person's sword grip.

The idea is that a person with a weak sword grip then has to rely more on the group for protection—reducing individual action. In recent years, prosthetic fingertips have been developed to disguise this distinctive appearance.[4]

Many yakuza have full-body tattoos (including their genitalia). These tattoos, known as irezumi in Japan, are still often "hand-poked", that is, the ink is inserted beneath the skin using non-electrical, hand-made and handheld tools with needles of sharpened bamboo or steel. The procedure is expensive, painful, and can take years to complete.[7]

When yakuza members play Oicho-Kabu cards with each other, they often remove their shirts or open them up and drape them around their waists. This enables them to display their full-body tattoos to each other. This is one of the few times that yakuza members display their tattoos to others, as they normally keep them concealed in public with long-sleeved and high-necked shirts. When new members join, they are often required to remove their trousers as well and reveal any lower body tattoos.

Syndicates

Four largest syndicates

Although yakuza membership has declined following an anti-gang law aimed specifically at yakuza and passed by the Japanese government in 1992, there are thought to be more than 58,000 active yakuza members in Japan today.[8] Although there are many different yakuza groups, together they form the largest organized crime group in the world.[9]

| Principal families | Description | Mon (crest) |

|---|---|---|

| Yamaguchi-gumi (六代目山口組 Rokudaime Yamaguchi-gumi) | The Yamaguchi-gumi is the biggest yakuza family, accounting for 50% of all yakuza in Japan, with more than 55,000 members divided into 850 clans. Despite more than one decade of police repression, the Yamaguchi-gumi has continued to grow. From its headquarters in Kobe, it directs criminal activities throughout Japan. It is also involved in operations in Asia and the United States. Shinobu Tsukasa, also known as Kenichi Shinoda, is the Yamaguchi-gumi's current oyabun. He follows an expansionist policy, and has increased operations in Tokyo (which has not traditionally been the territory of the Yamaguchi-gumi.)

The Yamaguchi family is successful to the point where its name has become synonymous with Japanese organized crime in many parts of Asia outside Japan. Many Chinese or Korean persons who do not know the name "Yakuza" would know the name "Yamaguchi-gumi", which is frequently portrayed in gangster films. |

"Yamabishi" (山菱) |

| Sumiyoshi-kai (住吉会) | The Sumiyoshi-kai is the second largest yakuza family, with 20,000 members divided into 277 clans. Sumiyoshi-kai is a confederation of smaller yakuza groups. Its current head (会長 oyabun) is Isao Seki. Structurally, Sumiyoshi-kai differs from its principal rival, the Yamaguchi-gumi, in that it functions like a federation. The chain of command is more lax, and its leadership is distributed among several other people. |  |

| Inagawa-kai (稲川会) | The Inagawa-kai is the third largest yakuza family in Japan, with roughly 15,000 members divided into 313 clans. It is based in the Tokyo-Yokohama area and was one of the first yakuza families to expand its operations to outside Japan. |  |

| Aizukotetsu-kai (六代目会津小鉄会 Rokudaime Aizukotetsu-kai) | The Aizukotetsu-kai is the fourth largest yakuza family in Japan, with roughly 7,000 members. Rather than a stand-alone gang, the Aizukotetsu-kai is a federation of approximately 100 of Kyoto's various yakuza groups. Its name comes from the Aizu region, "Kotetsu", a type of Japanese sword. Its main base is in Kyoto. |  |

Designated bōryokudan

A designated boryokudan (指定暴力団 Shitei Bōryokudan)[10] is a "particularly harmful" yakuza group[11] registered by the Prefectural Public Safety Commissions under the Organized Crime Countermeasures Law (暴力団対策法 Bōryokudan Taisaku Hō) enacted in 1991.[12]

Under the Organized Crime Countermeasures Law, the Prefectural Public Safety Commissions have registered 21 syndicates as the designated boryokudan groups.[13] Fukuoka Prefecture has the largest number of designated boryokudan groups among all of the prefectures, at 5; the Kudo-kai, the Taishu-kai, the Fukuhaku-kai, the Dojin-kai and the Namikawa-kai.[14]

Designated boryokudan groups are usually large, old-established organizations (mostly formed before World War II, some even formed before the Meiji Restoration of the 19th century), however there are some exceptions such as the Namikawa-kai which, with its blatant armed conflicts with the Dojin-kai, was registered only two years after its formation.

The numbers which follow the names of boryokudan groups refer to the group's leadership. For example, Yoshinori Watanabe headed the Yamaguchi-gumi fifth; on his retirement, Shinobu Tsukasa became head of the Yamaguchi-gumi sixth, and "Yamaguchi-gumi VI" is the group's formal name.

| Name | Japanese Name | Headquarters | Reg. in | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

六代目山口組 | Kobe, Hyogo | 1992 | Yamaguchi means the surname of the boss and kumi or gumi means group. |

| |

稲川会 | Minato, Tokyo | 1992 | Inagawa means the surname of the boss and kai means organization or society. It is a member of the Kantō-Shinboku-kai (Kanto social gathering). |

| |

住吉会 | Minato, Tokyo | 1992 | Sumiyoshi means the name of place. It is a member of the Kantō-Shinboku-kai. |

| |

六代目会津小鉄会 | Kyoto, Kyoto | 1992 | It was renamed from Aizu-Kotetsu in 1998. Aizu Kotetsu means the nickname of the first boss and Aizu means the name of place. |

| |

五代目工藤會 | Kitakyushu, Fukuoka | 1992 | It was renamed from Kudō-rengō-Kusano-ikka in 1999. Kudō means the surname of the boss. It is a member of the Yonsha-kai (Four social gathering). |

| |

旭琉會 | Okinawa, Okinawa | 1992 | It was renamed from Okinawa-Kyokuryū-kai in 2011. |

| |

五代目共政会 | Hiroshima, Hiroshima | 1992 | It is a member of the Gosha-kai (Five social gathering). |

| |

七代目合田一家 | Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi | 1992 | Gōda means the surname of the boss and ikka means family. It is a member of the Gosha-kai. |

| |

四代目小桜一家 | Kagoshima, Kagoshima | 1992 | |

| |

五代目浅野組 | Kasaoka, Okayama | 1992 | Asano means the surname of the boss. It is a member of the Gosha-kai. |

| |

道仁会 | Kurume, Fukuoka | 1992 | It is a member of the Yonsha-kai. |

| |

二代目親和会 | Takamatsu, Kagawa | 1992 | It is a member of the Gosha-kai. |

| |

双愛会 | Ichihara, Chiba | 1992 | It is a member of the Kantō-Shinboku-kai. |

| |

三代目俠道会 | Onomichi, Hiroshima | 1993 | It is a member of the Gosha-kai. |

| |

太州会 | Tagawa, Fukuoka | 1993 | Taishū means the nickname of the first boss. It is a member of the Yonsha-kai. |

| |

九代目酒梅組 | Osaka, Osaka | 1993 | |

| |

極東会 | Toshima, Tokyo | 1993 | Kyokutō means Far East. It is a member of the Kantō-Shinnō-Doushi-kai (Kanto Shennong Association). It is a tekiya group. |

| |

二代目東組 | Osaka, Osaka | 1993 | Azuma means the surname of the boss. |

| |

松葉会 | Taito, Tokyo | 1994 | Matsuba means pine needle, is kamon of the boss of predecessor syndicate Sekine-gumi. It is a member of the Kantō-Shinboku-kai. |

| |

三代目福博会 | Fukuoka, Fukuoka | 2000 | Fukuhaku means the name of place, Hakata Fukuoka. |

| Namikawa-kai | 浪川会 | Omuta, Fukuoka | 2008 | It was formed from split from Dojin-kai in 2006 and remained active until on June 11, 2013, when the senior members of the Kyushu Seido-kai said that the gang was disbanding to rejoin the Dojin-kai after resolving the problems the dispute had caused. On October 7, 2013 was formed the Namikawa-mutsumi-kai by upper members of the former Kyushu-Seido-kai when they visited a shrine in Kumamoto Prefecture when one member read aloud an oath announcing the formation of the new yakuza group, based in Omuta City, Fukuoka. Namikawa means the surname of the boss. |

| |

神戸山口組 | Awaji, Hyogo | 2016 | It was split of Yamaguchi-gumi VI in 2015. |

Designated bōryokudan in the past

| Name | Japanese Name | Headquarters | Designated in | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ishikawa-ikka | 石川一家 | Saga | 1993 - 1995 | Ishikawa means the surname of the boss. It was joined to the Yamaguchi-gumi V in 1995. |

| Dainippon-Heiwa-kai II | 二代目大日本平和会 | Hyogo | 1994 – 1997 | It was successor of Honda-kai. Dainippon means Great Japan and heiwa means peace. It was not designated update. |

| Kumamoto-rengō Yamano-kai III | 熊本連合 三代目山野会 | Kumamoto | 1998 – 2001 | Kumamoto means the name of place and rengo means coalition. Yamano means the surname of the boss. It was destroyed. |

| Kyokutō-Sakurai-sōke-rengō-kai | 極東桜井總家連合会 | Shizuoka | 1993 – 2005 | Sakurai means the surname of the boss, sōke means all family or head family and rengō-kai means federation. It disappeared. |

| Kokusui-kai | 國粹会 | Tokyo | 1994 – 2005 | Kokusui means Japanese nationalism. It was joined to the Yamaguchi-gumi VI. |

| Nakano-kai | 中野会 | Osaka | 1999 – 2005 | It was split from Yamaguchi-gumi in 1997. Nakano means the surname of the boss. It was disbanded in 2005. |

| Kyokuryū-kai IV | 四代目旭琉會 | Okinawa | 1992 – 2012 | It has been merged into Okinawa-Kyokuryū-kai in 2011. |

Other notable bōryokudan

| Name | Japanese name | Headquarters | Boss | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seishin-kai | 清心会 | Iwate | Ōta Seigo? (太田 清吾) | Its core is the Tokyo-Seidai-Hoshi-ikka-Ota III (東京盛代星一家太田三代目). |

| Genseida-Kōyū-kai | 源清田交友会 | Ibaraki | Shiroo Tanabe (田名辺 城男) | Its core is the Genseida-Tanabe III (源清田田名辺三代目). It had once belonged to the Zen-Nihon-Genseida-rengo-kai (全日本源清田連合会). |

| Matsuba-kai-Sekine-gumi | 松葉会関根組 | Ibaraki | Nariaki Ōtsuka (大塚 成晃) | It was split from Matsuba-kai in 2014. Sekine is the surname of the boss. |

| Chōrakuji-ikka III | 三代目長楽寺一家 | Tochigi | Kazuo Hori (堀 和雄) | |

| Yorii-sōke VII | 七代目寄居宗家 | Gunma | Kiyoshi Kawada? (川田 清史) | It withdrew from Kōdō-kai. Yorii is a place name and soke means head family. |

| Yorii-bunke V | 寄居分家五代目 | Gunma | Hiroshi Godai (五代 博) | Bunke means branch family. Member of the Kantō-Shinnō-Doushi-kai. |

| Kameya-ikka V | 五代目亀屋一家 | Saitama | Akira Shirahata? (白畑 晟) | It was split from Takezawa-kai. |

| Yoshiha-kai VII | 七代目吉羽会 | Saitama | Kiyomasa Nakamura (中村 清正) | It was split from Takezawa-kai. Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Takezawa-kai | 竹澤会 | Chiba | Haruo Ōtawa (太田和 春雄) | Formerly known as Zen-Takezawa-rengō-kai. Takezawa is the surname of the boss. Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Asakusa-Sanzun V | 五代目浅草三寸 | Tokyo | Yutaka Fujisaki (藤咲 豊) | Asakusa is a place name and sanzun is a kind of tekiya. |

| Anegasaki-kai | 姉ヶ崎会 | Tokyo | Shigetami Nakanome (中野目 重民) | Formerly known as Anegasaki-rengō-kai in 2006. Anegasaki is a place name. Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Iijima-kai VIII | 八代目飯島会 | Tokyo | Kanji Nishikawa? (西川 冠士) | Formerly known as Zen-Nihon-Iijima-rengō-kai. Iijima is the surname of the boss. Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Okaniwa-kai | 岡庭会 | Tokyo | Seiichirō Okaniwa (岡庭 清一郎) | Okaniwa is the surname of the boss. Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Kawaguchiya-kai | 川口家会 | Tokyo | Kiyoshi Osaka (大坂 清) | |

| Kanda-Takagi VII | 神田高木七代目 | Tokyo | Akira Nagamura (長村 昭) | Kanda is a place name and Takagi is the surname of the boss. |

| Shitaya-Hanajima-kai? | 下谷花島会 | Tokyo | Ōsaka Isamu]]? (大坂 勇) | Shitaya is a place name. Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Jōshūya-kai | 上州家会 | Tokyo | Katsuhiko Itō]] (伊藤 勝彦) | Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Shinmon-rengō-kai | 新門連合会 | Tokyo | Naoaki Kasama (笠間 直明) | It has inherited the genealogy of Shinmon Tatsugoro. |

| Sugitō-kai | 杉東会 | Tokyo | Tomoaki Nohara (野原 朝明) | Sugitō means east of Suginami. Formerly known as Sugitō-rengō-kai. Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Daigo-kai | 醍醐会 | Tokyo | Hideo Aoyama (青山 秀夫) | Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Chōjiya-kai | 丁字家会 | Tokyo | Gorō Yoshida]] (吉田 五郎) | Formerly known as Zen-Chōjiya-rengō-kai. Chōjiya means clove merchants. Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Tenjin'yama | 天神山 | Tokyo | unknown | Split from Kyokutō-kai. |

| Tōa-kai | 東亜会 | Tokyo | Yoshio Kaneumi (金海 芳雄) | Successor to Tōsei-kai]]. Tōa means East Asia. Member of the Kanto-Shinboku-kai. |

| Hashiya-kai | 箸家会 | Tokyo | Kōtarō Satō (佐藤 幸太郎) | Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Hanamata-kai | 花又会 | Tokyo | Akira Kiyono (清野 昭) | Formerly known as Hanamata-rengō-kai. Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Masuya-kai | 桝屋会 | Tokyo | Sotojirō Higashiura (東浦 外次郎) | Formerly known as Zen-Masuya-rengō-kai. Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Matsuzakaya-ikka V | 五代目松坂屋一家 | Tokyo | Takichi Nishimura (西村 太吉) | |

| Ryōgokuya-kai | 両国家会 | Tokyo | unknown | Formerly known as Zen-Ryōgokuya-rengō-kai. Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Ametoku-rengō-kai | 飴德連合会 | Kanagawa | Hideya Nagamochi? (永持 英哉) | Ametoku is the nickname of the first boss. Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Tokuriki-ikka V | 五代目徳力一家 | Kanagawa | unknown | Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Yokohama-Kaneko-kai | 横浜金子会 | Kanagawa | Takashi Terada (寺田 隆) | Yokohama is a place name and Kaneko is the surname of the boss. Member of the Kanto-Shinno-Doushi-kai. |

| Sakurai-sōke | 櫻井總家 | Shizuoka | Hiroyoshi Sano (佐野 宏好) | It is successor of Kyutō-Sakurai-sōke-rengō-kai. |

| Chūkyō-Shinnō-kai | 中京神農会 | Aichi | Eizō Yamagashira? (山頭 栄三) | It was split from Dōyū-kai. Chūkyō is a place name and Shinno is Shennong, a mythical sage ruler of prehistoric China. |

| Marutomi-rengō-kai | 丸富連合会 | Kyoto | Satoshi Kitahashi? (北橋 斉) | |

| Sanshaku-gumi-honke IV | 大阪四代目三尺組本家 | Osaka | Aizō Tanaka (田中 愛造) | |

| Naoshima-Giyū-kai | 直嶋義友会 | Osaka | Tadashi Noda (野田 忠志) | Naoshima is the surname of the boss. |

| Kōbe-Hakurō-kai-sōhonbu V | 五代目神戸博労会総本部 | Hyogo | Shikano Noboru? (鹿野 昇) | Kōbe and Hakurō is a place name. |

| Chūsei-kai | 忠成会 | Hyogo | Tadaaki Ōmori (大森 匡晃) | |

| Matsuura-gumi II | 二代目松浦組 | Hyogo | Kazuo Kasaoka (笠岡 一雄) | Matsuura is the surname of the boss. |

| Konjin-Tsumura-sōhonke II | 二代目金神津村總本家 | Hiroshima | Yoshisuke Tsumura? (津村 義輔) | Sōhonke means all family or head family. |

| Chūgoku-Takagi-kai III | 三代目中国高木会 | Hiroshima | Hideyoshi Daigen? (大源 秀吉) | Successor to Kyōsei-kai Murakami-gumi. Chūgoku is a place name and Takagi is the surname of the boss. |

| Kyūshū-Kashida-kai III | 三代目九州樫田会 | Fukuoka | Takashi Koga? (古賀 孝司) | Kyūshū is a place name and Kashida is the surname of the boss. |

| Tatekawa-kai? III | 九州三代目立川会 | Fukuoka | Toshihiko Ikeura (池浦 敏彦) | |

| Nakanishi-kai | 中西会 | Fukuoka | unknown | |

| Fujiie-kai? | 藤家会 | Fukuoka | Mitsuo Nakao (中尾 光男) | Fujiie is the surname of the boss. |

| Kyūshū-Kumashiro-rengō ? | 九州神代連合 | Saga | Katsuji Noguchi (野口 勝次) | |

| Kyūshū-Ozaki-kai II | 二代目九州尾崎会 | Nagasaki | Kuniyuki Koga (古賀 國行) | Ozaki is the surname of the boss. |

| Kumamoto-kai III | 三代目熊本會 | Kumamoto | Hidenori Morihara (森原 秀徳) | Successor to Kumamoto-rengō. Member of the Yonsha-kai. |

| Sanshin-kai | 山心会 | Kumamoto | Atsushi Inoue (井上 厚) | Successor to Kumamoto-rengō Yamano-kai. Formerly known as Sanshin-kai (山心会). |

| Murakami-gumi III | 九州三代目村上組 | Oita | Yoshishige Matsuoka (松岡 良茂) | Murakami is the surname of the boss. |

| Nishida-kai V | 五代目西田会 | Miyazaki | Kazuo Tanaka (田中 一夫) |

Other prominent boryokudan

| Name | Japanese name | Headquarters | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marumo-ikka | 丸茂一家 | Hokkaido | |

| Seiyū-kai | 誠友会 | Hokkaido | Merged with the Yamaguchi-gumi IV in 1985. |

| Zen-Chojiya-Hachiya-rengo-kai | 全丁字家蜂谷連合会 | Hokkaido | Disbanded in 1988, the remaining organizations have subscribed to Kenryu-kai and Kodo-kai. |

| Yorii-Sekiho-rengo | 寄居関保連合 | Hokkaido | Merged with the Yamaguchi-gumi. |

| Umeya-Abe-rengo-kai | 梅家阿部連合会 | Hokkaido | Merged with the Kodo-kai. |

| Kigure-ikka | 木暮一家 | Hokkaido | Merged with the Inagawa-kai. |

| Aizuya-ikka-Kodaka | 会津家一家小高 | Hokkaido | |

| Koshijiya-rengo | 越路家連合 | Hokkaido | Merged with the Inagawa-kai. |

| Kanto-Komatsuya-ikka | 関東小松家一家 | Hokkaido | |

| Oshu-Umeya-rengo-kai | 奥州梅家連合会 | Aomori | Merged with the Inagawa-kai. |

| Oshu-Saikaiya-so-rengo-kai | 奥州西海家総連合会 | Miyagi | Merged with the Sumiyoshi-kai. |

| Tokyo-Seidai-Nishikido-kai | 東京盛代錦戸会 | Miyagi | Merged with the Sumiyoshi-kai. |

| Tokyo-Seidai-Kawasaki-kai | 東京盛代川崎会 | Miyagi | Merged with the Sumiyoshi-kai. |

| Nishikata-ikka | 西方一家 | Miyagi | |

| Anegasaki-Yagami-kai | 姉ケ崎八神会 | Akita | Merged with the Inagawa-kai. |

| Aizuya-ikka-Nomoto | 会津家一家野本 | Akita | Merged with the Kyokuto-kai. |

| Oshu-Yamaguchi-rengo | 奥州山口連合 | Yamagata | Merged with the Sumiyoshi-kai. |

| Oshu-Aizu-Kakusada-ikka | 奥州会津角定一家 | Fukushima | Merged with the Yamaguchi-gumi. |

| Maruto-kai | 丸唐会 | Fukushima | Merged with the Sumiyoshi-kai. |

| Matsuba-kai-Doushi-kai | 松葉会同志会 | Ibaraki | Disbanded, then joined to the Matsuba-kai. |

| Shinwa-kai | 親和会 | Tochigi | Merged with the Sumiyoshi-kai. |

| Kochiya-kai | 河内家会 | Tochigi | Merged with the Kyokuto-kai. |

| Zennihon-Yorii-rengo-kai | 全日本寄居連合会 | Gunma | Disappeared. |

| Kanto-Kumaya-rengo | 関東熊屋連合 | Saitama | Merged with Kyokuto-kai. |

| Zennihon-Genseida-rengo-kai | 全日本源清田連合会 | Chiba | Disappeared. |

| Kanto-Chojamachi-kai | 関東長者町会 | Chiba | Merged with Sumiyoshi-kai. |

| Minato-kai | 港会 | Tokyo | Disbanded, then taken over by Sumiyoshi-kai. |

| Kohei-ikka | 幸平一家 | Tokyo | Merged with the Minato-kai. |

| Doshida-ikka | 圡支田一家 | Tokyo | |

| Sekine-gumi | 関根組 | Tokyo | Disbanded, then taken over by Matsuba-kai. |

| Ando-gumi (Azuma-kogyo) | 安東組 (東興業) | Tokyo | Disbanded. |

| Tosei-kai | 東声会 | Tokyo | Merged with the Yamaguchi-gumi, then disbanded and taken over by Toa-kai. |

| Koganei-ikka | 小金井一家 | Tokyo | Merged with the Nibiki-kai. |

| Nibiki-kai | 二率会 | Tokyo | Disbanded. |

| Hokusei-kai | 北星会 | Tokyo | Disbanded. |

| Kowa-kai | 交和会 | Tokyo | Successor to the Hokusei-kai. Merged with the Inagawa-kai. |

| Namai-ikka | 生井一家 | Tokyo | Merged with the Kokusui-kai. |

| Ochiai-ikka | 落合一家 | Tokyo | Merged with the Kokusui-kai. |

| Aizuya-rengo-kai | 會津家連合会 | Tokyo | Merged with the Goto-gumi. |

| Tokyo-Yasuda-kai | 東京安田会 | Tokyo | Merged with the Rachi-gumi. |

| Kanto-Hayashi-gumi-rengo-kai | 関東林組連合会 | Tokyo | |

| Kyokuto-Aio-rengo-kai | 極東愛桜連合会 | Tokyo | Disbanded in 1967. |

| Ishimoto-kai | 石元会 | Tokyo | |

| Ryogoku-kai | 両国会 | Tokyo | |

| Kinsei-kai | 錦政会 | Tokyo | |

| Joman-ikka | 上萬一家 | Tokyo | |

| Gijin-to | 義人党 | Kawasaki, Kanagawa | Disbanded. The successor organization has joined the Sumiyoshi-kai. |

| Kanto-Hayashi-gumi-rengo-kai | 関東林組連合会 | ||

| Yokohama-Saikaiya | 横浜西海家 | Kanagawa | Merged with the Kyokuto-kai. |

| Kawauchi-gumi | 川内組 | Fukui | Merged with the Sugatani-gumi. |

| Yamanashi-Kyōyū-kai | 山梨侠友會 | Yamanashi | Split from Inagawa-kai in 2011. "Yamanashi" refers the name of place. Disbanded in 2016, joined Inagawa-kai and renamed Sano-gumi. |

| Shinshu-Saito-ikka | 信州斎藤一家 | Nagano | |

| Yoshihama-kai | 芳浜会 | Gifu | |

| Ikeda-ikka | 池田一家 | Gifu | |

| Shimizu-ikka | 清水一家 | Shizuoka | Merged with the Yamaguchi-gumi. |

| 中泉一家 | Shizuoka | ||

| Reiganjima-Masuya-Hattori-kai | 霊岸島桝屋服部会 | Shizuoka | |

| Honganji-ikka | 本願寺一家 | Aichi | |

| Inabaji-ikka | 稲葉地一家 | Nagoya, Aichi | Merged with the Kodo-kai. |

| Unmeikyodo-kai | 運命共同会 | Aichi | Disbanded. |

| Hirai-ikka | 平井一家 | Toyohashi, Aichi | Merged with the Unmeikyodo-kai. |

| Tesshin-kai | 鉄心会 | Nagoya, Aichi | Merged with the Unmeikyodo-kai. |

| Chukyo-Asano-kai | 中京浅野会 | Aichi | Merged with the Unmeikyodo-kai. |

| Seto-ikka | 瀬戸一家 | Seto, Aichi | Merged with the Yamaguchi-gumi. |

| Doyu-kai | 導友会 | Nagoya, Aichi | Merged with the Kodo-kai. |

| Sankichi-ikka | 三吉一家 | Aichi | |

| Kira-ikka | 吉良一家 | Aichi | |

| Kusuriya-rengo-kai | 薬屋連合会 | Aichi | |

| Kumaya-ikka | 熊屋一家 | Aichi | |

| Nagoya-Chojamachi-ikka | 名古屋長者町一家 | Aichi | |

| Hiranoya-ikka | 平野家一家 | Nagoya, Aichi | Merged with the Kodo-kai. |

| Aio-kai | 愛桜会 | Mie | Merged with the Yamaguchi-gumi. |

| Kanbeya-ikka | 神戸屋一家 | Mie | |

| Shujiro-ikka | 周次郎一家 | ||

| Kamijo-gumi | 上條組 | Mie | |

| Ise-Kanbe-ikka | 伊勢神戸一家 | Mie | |

| Ise-Kawashima-ikka | 伊勢川島一家 | Mie | |

| Tsunan-ikka | 津南一家 | Mie | |

| Mizutani-ikka | 水谷一家 | Mie | Merged with the Yamaguchi-gumi. |

| Ise-Kamiya-ikka | 伊勢紙谷一家 | Mie | |

| Nakajima-rengo-kai | 中島連合会 | Kyoto | Merged with the Aizu-Kotetsu-kai. |

| Sunakogawa-gumi | 砂子川組 | Osaka | Descended of Aizu Kotetsu. |

| Nakamasa-gumi | 中政組 | Osaka | Descended from of Aizu Kotetsu. |

| 小久一家 | Osaka | ||

| 長政 | Osaka | ||

| Dankuma-kai | 淡熊会 | Osaka, Osaka | |

| Yamato-Nara-gumi | 倭奈良組 | Osaka | |

| Dajokan | 大政官 | Osaka | |

| I-rengo | い聯合 | Osaka | |

| Yamaguchi-gumi Yanagawa-gumi | 山口組 柳川組 | Osaka | |

| Hayano-kai | 早野会 | Osaka | |

| Oguruma-Makoto-kai | 小車誠会 | Osaka | |

| Imanishi-gumi | 今西組 | Osaka | Merged with the Sakaume-gumi. |

| Ono-ikka | 大野一家 | Osaka | |

| Minami-ikka | 南一家 | Osaka | |

| Sumida-kai | 澄田会 | Osaka | |

| Matsuda-gumi (Matsuda-rengo) | 松田組 (松田連合) | Osaka | |

| Hadani-gumi | 波谷組 | Osaka | Disbanded in 1994. |

| Komasa-gumi | 小政組 | Osaka | |

| Doi-gumi | 土井組 | Osaka | |

| 九紋龍組 | Osaka | ||

| Oshima-gumi | 大嶋組 | Hyogo | |

| Honda-kai | 本多会 | Hyogo | |

| Ichiwa-kai | 一和会 | Hyogo | Disbanded. |

| Suwa-ikka | 諏訪一家 | Hyogo | |

| Sasaki-gumi | 佐々木組 | Wakayama | |

| Takenaka-gumi | 竹中組 | Okayama | Withdrew from the Yamaguchi-gumi. |

| Kinoshita-kai | 木下会 | Okayama | |

| Takahashi-gumi | 高橋組 | Onomichi, Hiroshima | |

| Katsuura-kai | 勝浦会 | Tokushima | Disbanded in 1998. |

| Mori-kai | 森会 | Tokushima | |

| Matsuyama-rengo-kai | 松山連合会 | Ehime | Merged with the Yamaguchi-gumi. |

| Kyushu-Kyoyu-rengo-kai | 九州侠友連合会 | Fukuoka | |

| Seibu-rengo | 西武連合 | Karatsu, Saga | |

| Kumamoto-rengo | 熊本連合 | Kumamoto | |

| Kitaoka-kai | 北岡会 | Kumamoto | |

| Daimon-kai | 大門会 | Kumamoto |

Current activities

Japan

Yakuza are regarded as semi-legitimate organizations. For example, immediately after the Kobe earthquake, the Yamaguchi-gumi, whose headquarters are in Kobe, mobilized itself to provide disaster relief services (including the use of a helicopter), and this was widely reported by the media as a contrast to the much slower response by the Japanese government.[15][16] The yakuza repeated their aid after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, with groups opening their offices to refugees and sending dozens of trucks with supplies to affected areas.[17] For this reason, many yakuza regard their income and hustle (shinogi) as a collection of a feudal tax.

Many yakuza syndicates, notably the Yamaguchi-gumi, officially forbid their members from engaging in drug trafficking, while some yakuza syndicates, notably the Dojin-kai, are heavily involved in it.

Some yakuza groups are known to deal extensively in human trafficking.[19] The Philippines, for instance, is a source of young women. Yakuza trick girls from impoverished villages into coming to Japan, where they are promised respectable jobs with good wages. Instead, they are forced into becoming prostitutes and strippers.[20]

Yakuza frequently engage in a unique form of Japanese extortion known as sōkaiya. In essence, this is a specialized form of protection racket. Instead of harassing small businesses, the yakuza harasses a stockholders' meeting of a larger corporation. They simply scare the ordinary stockholder with the presence of yakuza operatives, who obtain the right to attend the meeting by making a small purchase of stock.

Yakuza also have ties to the Japanese realty market and banking, through jiageya. Jiageya specialize in inducing holders of small real estate to sell their property so that estate companies can carry out much larger development plans. Japan's bubble economy of the 1980s is often blamed on real estate speculation by banking subsidiaries. After the collapse of the Japanese property bubble, a manager of a major bank in Nagoya was assassinated, and much speculation ensued about the banking industry's indirect connection to the Japanese underworld.[21]

Yakuza have been known to make large investments in legitimate, mainstream companies. In 1989, Susumu Ishii, the Oyabun of the Inagawa-kai (a well known yakuza group) bought US$255 million worth of Tokyo Kyuko Electric Railway's stock.[22] Japan's Securities and Exchange Surveillance Commission has knowledge of more than 50 listed companies with ties to organized crime, and in March 2008, the Osaka Securities Exchange decided to review all listed companies and expel those with yakuza ties.[23]

As a matter of principle, theft is not recognised as a legitimate activity of yakuza. This is in line with the idea that their activities are semi-open; theft by definition would be a covert activity. More importantly, such an act would be considered a trespass by the community. Also, yakuza usually do not conduct the actual business operation by themselves. Core business activities such as merchandising, loan sharking or management of gambling houses are typically managed by non-yakuza members who pay protection fees for their activities.

There is much evidence of yakuza involvement in international crime. There are many tattooed yakuza members imprisoned in various Asian prisons for such crimes as drug trafficking and arms smuggling. In 1997, one verified yakuza member was caught smuggling 4 kilograms (8.82 pounds) of heroin into Canada.

Prior to his death in 1980, former Italian-American Mafia member Mickey Zaffarano, who controlled pornography rackets across the United States for the Bonanno family, was overheard talking about the enormous profits from the pornography trade that both families could make together.[24] Another yakuza racket is bringing women of other ethnicities/races, especially East European[24] and Asian,[24] to Japan under the lure of a glamorous position, then forcing the women into prostitution.[25]

Because of their history as a legitimate feudal organization and their connection to the Japanese political system through the uyoku (extreme right-wing political groups), yakuza are somewhat a part of the Japanese establishment, with six fan magazines reporting on their activities.[26] Yakuza involvement in politics functions similarly to that of a lobbying group, with them backing those who share in their opinions or beliefs.[27] One study found that 1 in 10 adults under the age of 40 believed that the yakuza should be allowed to exist.[17] In the 1980s in Fukuoka, a yakuza war spiraled out of control and civilians were hurt. It was a large conflict between the Yamaguchi-gumi and Dojin-kai, called the Yama-Michi War. The police stepped in and forced the yakuza bosses on both sides to declare a truce in public.

At various times, people in Japanese cities have launched anti-yakuza campaigns with mixed and varied success. In March 1995, the Japanese government passed the Act for Prevention of Unlawful Activities by Criminal Gang Members, which made traditional racketeering much more difficult. Beginning in 2009, led by agency chief Takaharu Ando, Japanese police began to crack down on the gangs. Kodo-kai chief Kiyoshi Takayama was arrested in late 2010. In December 2010, police arrested Yamaguchi-gumi's alleged number three leader, Tadashi Irie. According to the media, encouraged by tougher anti-yakuza laws and legislation, local governments and construction companies have begun to shun or ban yakuza activities or involvement in their communities or construction projects.[28] The police are handicapped, however, by Japan's lack of an equivalent to plea bargaining, witness protection, or the United States' Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act.[23] Laws were enacted in Osaka and Tokyo in 2010 and 2011 to try to combat yakuza influence by making it illegal for any business to do business with the yakuza.[29][30]

Yakuza's aid in Tōhoku catastrophe

Following the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami on 11 March 2011, the yakuza sent hundreds of trucks filled with food, water, blankets, and sanitary accessories to aid the people in the affected areas of the natural disaster. CNN México said that although the yakuza operates through extortion and other violent methods, they "[moved] swiftly and quietly to provide aid to those most in need."[31] Such actions by the yakuza are a result of their knowing of what it is like to "fend for yourself," without any government aid or community support, because they are also considered "outcast" and "dropouts from society".[31] In addition, the yakuza's code of honor (ninkyo) reportedly values justice and duty above anything else, and forbids allowing others to suffer.[32]

United States

Yakuza activity in the United States is mostly relegated to Hawaii, but they have made their presence known in other parts of the country, especially in Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area, as well as Seattle, Las Vegas, Arizona, Virginia, Chicago, and New York City.[33][34] The Yakuza are said to use Hawaii as a midway station between Japan and mainland America, smuggling methamphetamine into the country and smuggling firearms back to Japan. They easily fit into the local population, since many tourists from Japan and other Asian countries visit the islands on a regular basis, and there is a large population of residents who are of full or partial Japanese descent. They also work with local gangs, funneling Japanese tourists to gambling parlors and brothels.[33]

In California, the Yakuza have made alliances with local Vietnamese and Korean gangs as well as Chinese triads, with Vietnamese as the most common alliance. The alliances with Vietnamese gangs dated back in the late 1980s, and most Vietnamese gangsters were used as muscle, as they had potential to become extremely violent as needed. (Yakuza saw the potential following the constant Vietnamese cafe shoot outs, and home invasion burglaries throughout the 1980s and early 1990s). In New York City, they appear to collect finders fees from Russian, Irish and Italian mafiosos and businessmen for guiding Japanese tourists to gambling establishments, both legal and illegal.[33]

Handguns manufactured in the US account for a large share (33%) of handguns seized in Japan, followed by China (16%), and the Philippines (10%). In 1990, a Smith & Wesson .38 caliber revolver that cost $275 in the US could sell for up to $4,000 in Tokyo. By 1997 it would sell for only $500, due to the proliferation of guns in Japan during the 1990s.[34]

The FBI suspects that the Yakuza use various operations to launder money in the U.S.[23]

In 2001, the FBI's representative in Tokyo arranged for Tadamasa Goto, the head of the group Goto-gumi, to receive a liver transplant at the UCLA Medical Center in the United States, in return for information of Yamaguchi-gumi operations in the US. This was done without prior consultation of the NPA. The journalist who uncovered the deal received threats by Goto and was given police protection in the US and in Japan.[23]

North Korea

In 2009, yakuza member Yoshiaki Sawada was released from North Korea after spending five years in the country for attempting to bribe a North Korean official and smuggle drugs.[35]

Constituent members

According to a 2006 speech by Mitsuhiro Suganuma, a former officer of the Public Security Intelligence Agency, around 60 percent of yakuza members come from burakumin, the descendants of a feudal outcast class and approximately 30 percent of them are Japanese-born Koreans, and only 10 percent are from non-burakumin Japanese and Chinese ethnic groups.[36][37]

Burakumin

The burakumin are a group that is socially discriminated against in Japanese society, whose recorded history goes back to the Heian period in the 11th century. The burakumin are descendants of outcast communities of the pre-modern, especially the feudal era, mainly those with occupations considered tainted with death or ritual impurity, such as butchers, executioners, undertakers, or leather workers. They traditionally lived in their own secluded hamlets.

According to David E. Kaplan and Alec Dubro, burakumin account for about 70% of the members of Yamaguchi-gumi, the largest yakuza syndicate in Japan.[38]

Ethnic Koreans

While ethnic Koreans make up only 0.5% of the Japanese population, they are a prominent part of yakuza, perhaps because they suffer severe discrimination in Japanese society alongside the burakumin.[39][40] In the early 1990s, 18 of 90 top bosses of Inagawa-kai were ethnic Koreans. The Japanese National Police Agency suggested Koreans composed 10% of the yakuza proper and 70% of burakumin in the Yamaguchi-gumi.[39] Some of the representatives of the designated Bōryokudan are also.[41] The Korean significance had been an untouchable taboo in Japan and one of the reasons that the Japanese version of Kaplan and Dubro's Yakuza (1986) had not been published until 1991 with the deletion of Korean-related descriptions of the Yamaguchi-gumi.[42]

Japanese-born people of Korean ancestry are considered resident aliens because of their nationality and are often shunned in legitimate trades, and are therefore embraced by the yakuza precisely because they fit the group's "outsider" image.[43][6] Notable yakuza members of Korean ancestry include Hisayuki Machii, the founder of the Tosei-kai, Tokutaro Takayama, the president of the 4th-generation Aizukotetsu-kai, Jiro Kiyota, the president of the 5th-generation Inagawa-kai, Hirofumi Hashimoto, the head of the Kyokushinrengo-kai, and the bosses of the 6th / 7th Sakaume-gumi.

Indirect enforcement

Since 2011, regulations that made business with members illegal as well as enactments of Yakuza exclusion ordinances led to the group's membership decline from its 21st century peak. Methods include that which brought down Al Capone; checking the organization's finance. The Financial Services Agency ordered Mizuho Financial Group Inc. to improve compliance and that its top executives report by 28 October 2013 what they knew and when about a consumer-credit affiliate found making loans to crime groups. This adds pressure to the group from the U.S. as well where an executive order in 2011 required financial institutions to freeze yakuza assets. As of 2013, the U.S. Treasury Department has frozen about US$55,000 of yakuza holdings, including two Japan-issued American Express cards.[44]

Legacy

Yakuza in society

The Yakuza have had mixed relations with Japanese society. They function as a police force in their areas of operation, to help reduce crime, crime that would be their competition. They also provide protection to businesses and relief in times of disaster. These actions have painted yakuza in a fairly positive light within Japan. The gang-wars, and the use of violence as a tool, have caused their approval fall with the general public.[45]

Movies

The Yakuza have been represented in media and culture in many different fashions. Creating its own genre of movies within Japan's film industry the portrayal of the Yakuza mainly manifests in one of two archetypes; they are portrayed as either honorable and respectable men or as criminals who use fear and violence as their means of operation.[46] Movies like Dead or Alive or Graveyard of Honor portray some of the members as violent criminals, with the focus being on the violence, while other movies like Sonatine and Outrage focus more on the "business" side of the Yakuza.

Television

The Yakuza play a very important role in the Hawaii Five-0 remake. Lead character Kono Kalakaua's husband Adam Noshimuri was the former head of the Yakuza who took over after his father Hiro Noshimuri died. Adam's brother Michael Noshimuri was also part of the Yakuza.

Video games

The video game series Yakuza, portrays the actions of several different ranking members of the Yakuza throughout the series. The series addresses some of the same themes as the Yakuza genre of film does, like violence, honor, politics of the syndicates, etc. The series has been moderately successful; spawning sequels, spin-offs, a live action movie and a web TV series.

See also

- 893239 or Yakuza-Nijusan-Ku

- Bōsōzoku

- Crime in Japan

- Criminal tattoo

- Irezumi

- Kkangpae (Korean mafia)

- List of criminal enterprises, gangs and syndicates

- Mafia

- Organized crime

- Punch perm

- Russian mafia

- Triads

- Yakuza exclusion ordinances

References

- ↑ "Criminal Investigation: Fight Against Organized Crime (1)" (PDF). Overview of Japanese Police. National Police Agency. June 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ↑ Corkill, Edan, "Ex-Tokyo cop speaks out on a life fighting gangs — and what you can do", Japan Times, 6 November 2011, p. 7.

- 1 2 Kaplan, David; Dubro, Alec (2004), Yakuza: Japan's Criminal Underworld, pp. 18–21, ISBN 0520274903.

- 1 2 Bruno, Anthony. "The Yakuza - Oyabun-Kobun, Father-Child". truTV. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ↑ The Yakuza, the Japanese Mafia - The Crime Library - Crime Library on truTV.com

- 1 2 "The yakuza: Inside Japan's murky criminal underworld". CNN.

- ↑ Japanorama, BBC Three, Series 2, Episode 3, first aired 21 September 2006

- ↑

- ↑ Johnston, Eric, "From rackets to real estate, yakuza multifaceted", Japan Times, 14 February 2007, p. 3.

- ↑ "Police of Japan 2011, Criminal Investigation : 2. Fight Against Organized Crime", December 2009, National Police Agency

- ↑ "The Organized Crime Countermeasures Law", The Fukuoka Prefectural Center for the Elimination of Boryokudan (in Japanese)

- ↑ "Boryokudan Comprehensive Measures — The Condition of the Boryokudan", December 2010, Hokkaido Prefectural Police (in Japanese)

- ↑ "List of Designated Bōryokudan", 24 February 2011, Nagasaki Prefectural Police (in Japanese)

- ↑ "Retrospection and Outlook of Crime Measure", p.15, Masahiro Tamura, 2009, National Police Agency (in Japanese)

- ↑ Sterngold, James (22 January 1995), Quake in Japan: Gangsters; Gang in Kobe Organizes Aid for People In Quake, The New York Times.

- ↑ Sawada, Yasuyuki; Simizutani, Satoshi (2008), "How Do People Cope with Natural Disasters? Evidence from the Great Hanshin-Awaji (Kobe) Earthquake in 1995", Journal of Money, Credit and Banking (40:2–3), pp. 463–88.

- 1 2 Adelstein, Jake (2011-03-18). "Yakuza to the Rescue". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2011-03-18.

- ↑ "The Last Yakuza", 3 August 2010, World Policy Institute

- ↑ "HumanTrafficking.org, "Human Trafficking in Japan"".

- ↑ The Yakuza, the Japanese Mafia - The Crime Library - Crime Library on truTV.com

- ↑ "US clamps down on Japanese Yakuza mafia". Financial Times.

- ↑ Dubro, Alec; Kaplan, David E, Yakuza: Japan's Criminal Underworld, Questia.

- 1 2 3 4 Jake Adelstein. This Mob Is Big in Japan, The Washington Post, 11 May 2008

- 1 2 3 Kaplan and Dubro; Yakuza: Expanded Edition (2003, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21562-1)

- ↑ The Yakuza, the Japanese Mafia - The Crime Library — Criminal Enterprises — Crime Library on truTV.com

- ↑ "The Yakuza's Ties to the Japanese Right Wing". Vice Today.

- ↑ "The Yakuza Lobby". Foreign Policy.

- ↑ Zeller, Frank (AFP-Jiji), "Yakuza served notice days of looking the other way are over," Japan Times, 26 January 2011, p. 3.

- ↑ Botting, Geoff, "Average Joe could be collateral damage in war against yakuza", Japan Times, 16 October 2011, p. 9.

- ↑ Schreiber, Mark, "Anti-yakuza laws are taking their toll", Japan Times, 4 March 2012, p. 9.

- 1 2 "La mafia japonesa de los 'yakuza' envía alimentos a las víctimas del sismo". CNN México (in Spanish). 25 March 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ↑ Yue Jones, Terril (25 March 2011). "Yakuza among first with relief supplies in Japan". Reuters. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 Yakuza, Crimelibrary.com

- 1 2 Yakuza: Japan's Criminal Underworld (2003) Kaplan, D. & Dubro, A Part IV

- ↑ Yakuza returns after five years in North Korea jail on drug charge 2009-01-16 The Japan Times

- ↑ "Mitsuhiro Suganuma, "Japan's Intelligence Services"". The Foreign Correspondents' Club of Japan.

- ↑ "Capital punishment - Japan's yakuza vie for control of Tokyo". Jane’s Intelligence Review: 4. December 2009.

Around 60% of yakuza members come from burakumin, the descendants of a feudal outcast class, according to a 2006 speech by Mitsuhiro Suganuma, a former officer of the Public Security Intelligence Agency. He also said that approximately 30% of them are Japanese-born Koreans, and only 10% are from non-burakumin Japanese and Chinese ethnic groups.

Archived by the author - ↑ Dubro, Alec and David Kaplan, Yakuza: The Explosive Account of Japan's Criminal Underworld (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., 1986).

- 1 2 Yakuza: Japan's Criminal Underworld (2003) Kaplan, D. & Dubro, A. p. 133.

- ↑ KRISTOF, NICHOLAS (1995-11-30). "Japan's Invisible Minority: Better Off Than in Past, but StillOutcasts". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ↑ (in Japanese) "Boryokudan Situation in the Early 2007", National Police Agency, 2007, p. 22. See also Bōryokudan#Designated bōryokudan.

- ↑ Kaplan and Dubro (2003) Preface to the new edition.

- ↑ Bruno, A. (2007). "The Yakuza, the Japanese Mafia" CrimeLibrary: Time Warner

- ↑ "Yakuza Bosses Whacked by Regulators Freezing AmEx Cards". Bloomberg.

- ↑ "Where Have Japan’s Yakuza Gone?". Daily Beast.

- ↑ "Yakuza: Kind-hearted criminals or monsters in suits?". Japan Today.

Bibliography

- Bruno, A. (2007). "The Yakuza, the Japanese Mafia" CrimeLibrary: Time Warner

- Kaplan, David, Dubro Alec. (1986). Yakuza Addison-Wesley (ISBN 0-201-11151-9)

- Kaplan, David, Dubro Alec. (2003). Yakuza: Expanded Edition University of California Press (ISBN 0-520-21562-1)

- Hill, Peter B.E. (2003). The Japanese Mafia: Yakuza, Law, and the State Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-925752-3)

- Johnson, David T. (2001). The Japanese Way of Justice: Prosecuting Crime in Japan Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-511986-X)

- Miyazaki, Manabu. (2005) Toppamono: Outlaw. Radical. Suspect. My Life in Japan's Underworld Kotan Publishing (ISBN 0-9701716-2-5)

- Seymour, Christopher. (1996). Yakuza Diary Atlantic Monthly Press (ISBN 0-87113-604-X)

- Saga, Junichi., Bester, John. (1991) Confessions of a Yakuza: A Life in Japan's Underworld Kodansha America

- Schilling, Mark. (2003). The Yakuza Movie Book Stone Bridge Press (ISBN 1-880656-76-0)

- Sterling, Claire. (1994). Thieves' World Simon & Schuster (ISBN 0-671-74997-8)

- Sho Fumimura (Writer), Ryoichi Ikegami (Artist). (Series 1993-1997) "Sanctuary" Viz Communications Inc (Vol 1: ISBN 0-929279-97-2; Vol 2:ISBN 0-929279-99-9; Vol 3: ISBN 1-56931-042-4; Vol 4: ISBN 1-56931-039-4; Vol 5: ISBN 1-56931-112-9; Vol 6: ISBN 1-56931-199-4; Vol 7: ISBN 1-56931-184-6; Vol 8: ISBN 1-56931-207-9; Vol 9: ISBN 1-56931-235-4)

- Tendo, Shoko (2007). Yakuza Moon: Memoirs of a Gangster's Daughter Kodansha International (ISBN 978-4-7700-3042-9)

- Young Yakuza. Dir. Jean-Pierre Limosin. Cinema Epoch, 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yakuza. |

- 101 East – Battling the Yakuza—Al Jazeera (Video)

- https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/organized-crime#Asian-TOC

- Yakuza Portal site

- Blood ties: Yakuza daughter lifts lid on hidden hell of gangsters' families

- Crime Library: Yakuza

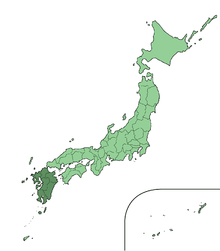

- Yakuza distribution map

- Japanese Mayor Shot Dead; CBS News, 17 April 2007

- Yakuza: The Japanese Mafia

- Yakuza distribution map

- Yakuza: Kind-hearted criminals or monsters in suits?